China Insight

Battling the Keyboard Warriors: How China’s Netizens Address Online Harassment

Incidents of online harassment against women continue to rise year on year across the world, with severe cases in the PRC and abroad. What’s on Weibo’s Cat Hanson, who has personally experienced online stalking in China, explores how cyber-bullying is gradually receiving more awareness – although the Chinese laws are lagging behind.

Published

7 years agoon

Incidents of online harassment against women continue to rise year on year across the world, with severe cases in the PRC and abroad. What’s on Weibo’s Cat Hanson, who has personally experienced online stalking in China, explores how cyber-bullying is gradually receiving more awareness – although the Chinese laws are lagging behind.

In the summer of 2016, romantic comedy So I Married my Anti-Fan (所以…和黑粉结婚了) released in theaters across China. Actress Yuan Shanshan (袁姗姗) starred as a scorned journalist who unleashes an online campaign against a Korean pop idol (Park Chanyeol). In the movie, Yuan’s character spends hours leaving insulting comments about the star in her crosshairs, giggling with glee as she argues with his diehard fans.

The role wasn’t entirely fiction for Yuan, who in 2013 became the target of a deluge of online abuse on China’s Sina Weibo.

The actress shared her experience during a TEDx presentation in Ningbo two years later, describing her shock of waking up to thousands of comments and posts criticizing her acting: “Before 2013, I would never in my wildest dreams have imagined that I’d become the internet’s troll-fodder,” she said.

Actress Yuan Shanshan addresses cyber bullying during a Ted Talk.

Yuan was not alone. In late 2016, Chinese women’s rights group Chilli Pepper (尖椒部落) published figures obtained from their survey on online harassment, also known in Mandarin as wangluobaoli (网络暴力 – a homonym of ‘online violence’ and ‘online bully’).

The report aimed to show that “Internet harassment is another form of violence.” According to the data, the majority of respondents were female students who had encountered online harassment in the past.

IDEAS ON ‘ONLINE VIOLENCE’ IN CHINA

“Chinese websites tend to blame young people’s ‘impulsive’ and ‘ignorant’ behaviour for the rise in online harassment.”

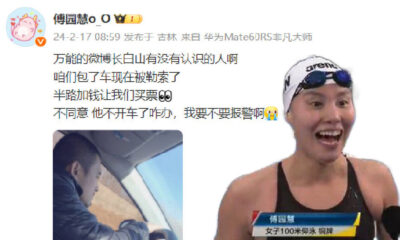

Discourse on China’s online violence has usually revolved around infamous ‘human flesh searches’ (人肉搜索), a term used to describe the activities of the wangluo baomin (网络暴民 ‘internet mob’) who seek out and share the personal information of people involved in public scandals.

The so-called ‘human flesh search’ is a collective effort of netizens to find out details about their online target.

Due to the internet’s comparatively youthful demographic and the aggressive nature of these search campaigns, Chinese Wikipedia-style websites tend to blame young people’s ‘impulsive’ and ‘ignorant’ behaviour for the rise in online harassment.

In contrast, the majority of Chilli Pepper’s survey respondents reported a style of online harassment beyond ‘human flesh searches.’ They also believe the issue is rooted in gender discrimination.

Given the varying opinions between online women’s groups and encyclopedic websites, it begs the question as to whether online platforms like Weibo are becoming a discursive space for issues of gender, abuse, and harassment.

GLOBAL ONLINE VIOLENCE

“Online misogyny is a global tragedy, and it is imperative that it ends.”

The online harassment of young women is not unique to China. Writing for The Guardian, Elle Hunt reported that over three-quarters of women reporting harassment were under 30 years old, according to Australian research.

In 2016, American actress and activist Ashley Judd delivered a TED Talk claiming: “Online misogyny is a global tragedy, and it is imperative that it ends.” The talk was internationally praised and shared on multiple social networking sites including Weibo.

The mechanisms of online violence in Australia and America were consistent with Chilli Pepper’s findings in China; harassment, hyper-sexualised comments, and attacks on appearance. The LGBT community are also regularly targeted worldwide with homophobic and transphobic online attacks.

Other factors such as money, crime, and morality are less likely to be the subject of harassment, despite being the main focus of human flesh searches. This suggests that a form of online violence exists outside of these searches, in contrast with online definitions.

“How many deaths before you’re satisfied?”

Incidents of online harassment against women continue to rise year on year across the world, with severe cases in China and abroad.

In June 2016, a man named as ‘Aidyn C’ was ordered to stand trial in the Netherlands for ‘extortion, internet luring and child pornography’ after the death of Canadian teenager Amanda Todd. The teenager posted a video to YouTube about her online harasser shortly before taking her own life. The case sent shockwaves throughout Canada and the world, leading to calls for stronger laws to combat online harassment.

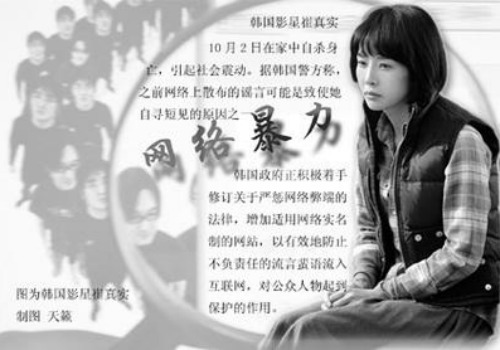

In China, the death of Chinese singer Qiao Renliang (乔任梁) was also followed by public outcry over online violence. The television actor and singer committed suicide in November 2016 at the age of 28. Qiao’s death was officially attributed to depression, although many netizens blamed the online abuse that stars such as Qiao and actress Yuan Shanshan receive on a daily basis.

Qiao’s death was officially attributed to depression, but many netizens blamed online abuse.

In a critical post addressed to online anti-fans, Weibo user @Lun_少女依 wrote: “How many deaths before you’re satisfied?”

Qiao Renliang’s death has never been officially connected to online harassment.

THE VULNERABLE ONES

“A high number of children aged 8-17 in China have undergone negative experiences online, ranking first among 25 countries.”

Despite evidence that young women and public figures are most vulnerable to online harassment, figures obtained by Microsoft in 2012 show that a disproportionately high number of children aged 8-17 in China have undergone ‘negative experiences’ over the internet, ranking first among 25 countries.

Some netizens dispute the reliability of these research projects. After China ranked 8th in internet civility in another study by Microsoft, a netizen wrote: “The software is still in the early stages. The words they search for [in these studies] are only one part of the Chinese language; there are still loads of other words created by internet users.”*

However, China ranked above average for education and formal school policies about online bullying, with almost half of the children surveyed having been made aware of online risks and ‘manners’ by their parents.

Microsoft believes that China demonstrates a high awareness of online bullying, however preventative and punitive measures are yet to receive legislative support.

*(Chinese netizens often create new ways to circumvent censorship or have an own online language. A famous example is the 3-character phrase ‘cao ni ma’ (草泥马), literally meaning ‘grass mud horse’, but pronounced in the same way as the vulgar “f*ck your mother”, which is written with three different characters. Netizens can thus say ‘f*ck you’ without this being picked up as such by software).

TACKLING ONLINE VIOLENCE

“I’m sorry for what I said about you.”

For Yuan Shanshan, the online and media abuse became so overwhelming that she was compelled to take action. Yuan eventually devised a campaign called”“Loving Criticism” (爱的骂骂). Phonetically similar to the phrase “a mother’s love,” Yuan pledged to donate 0.5 RMB to a children’s charity for every comment she received.

After twenty-four hours, she had raised over 50,000 RMB (±7270$). Across her Weibo a similar message was echoed hundreds of times: “I’m sorry for what I said about you.”

Yuan concluded her talk by mentioning the risk of suicide for the victims of online harassment. The actress advised young people to step away from the screens and find support via family, friends, and exercise.

Meanwhile, respondents to Chilli Pepper’s survey were asked for the best methods of combating online harassment. Ranking above answers such as ‘blocking the offender’ or confronting them with the same tactics, the majority favored reporting the harassment to social media platforms or the police. However, the legal parameters of online violence remain open to interpretation.

ONLINE VIOLENCE & CHINESE LAW

“The police suggested that I confront the harasser myself.”

Global laws on internet harassment are often unclear, although attitudes are changing. In 2016 while living in China, I reported an incident of online harassment by a local man to police. The cyber-stalking campaign of abuse and hyper-sexualised messages had lasted almost nine months. With no way to identify him other than several social media accounts, a legal channel seemed difficult to pursue.

After reviewing the messages, local police were sympathetic. However, the abuser had stopped short of directly threatening my life, which would have been a clear crime under law. It was later suggested that I confront the harasser myself. Knowing the abuser ranked collecting pen knives and pellet guns amongst his main hobbies, I maintained radio silence until the abuser went away.

Perpetrators of online violence are by no means immune to prosecution, and they can be prosecuted under existing laws both in China and around the world. In 2014, the South China Morning Post reported the arrest of a 20-year-old man in Hong Kong for posting violent death threats to an online forum regarding the daughter of a police officer.

Other nations in the region have been forced to amend existing laws to cover online crime. For example, Japan added online communications to the legal definition of stalking after the murder of two women. Gota Tsutsui sent malicious emails to one of the women before stabbing them to death in 2011.

In 2015 India also convicted a man for cyber-stalking in a case considered to be a first in the country. The BBC reported similar attitudes from the Indian police to those in the case in Hong Kong and my own in mainland China – a focus on finding evidence of physical threats sent via the internet rather than sexual harassment and stalking. It seems that like many countries, China is undergoing a transformative period in its legal recognition of online violence.

THE ROLE OF WEIBO

“Netizens should not give online violence a chance to flourish.”

Despite China reforming sexual harassment laws in real public spaces, the topic can still be considered taboo. However on Weibo, some netizens have taken to exposing or confronting their abusers, sharing articles and engaging in discussion. Internet anonymity apparently works both ways – masking the perpetrators of online violence, but also encouraging the abused party to bypass social taboos, speak frankly about their experiences, and generate conversation over the issue.

“Insulting people on the internet is against the law and lacking in education. Everyone should be civilized and respect one another. If you see these ‘keyboard warriors’ and ‘flamers’, report them to the police!”, was one comment among many.

Netizens not only feel empowered to call out online violence on Weibo, but also to propose solutions and changes to the law. A video of famed public speaker Wang Fan presenting her thoughts on the issues received thousands of re-blogs and comments:

“I suggest implementing a system that identifies internet users, such as needing your ID number to set up a Weibo account,” said one user.

“You can’t force people into having a good moral character, but you can emphasize the importance of having a good moral character” (source).

“If the big microbloggers get threatened, they can call the police to sort it out. What about us regular folk?” (source).

“I wish the police could sort out these ‘keyboard warriors’, these internet bullies who curse others as soon as they open their mouths – I’ve gathered all the evidence…The People’s Daily said earlier: ‘Keyboard warriors are not outside of the law!'” (source).

While debate over the need for clarity in online violence laws is ongoing, discourse continues to grow on Weibo. There are also indications that netizens aren’t the only ones who use the platform to raise awareness of the pressing nature of the issue, or even to link online violence with gender.

Earlier this year, the Weibo account for the Centre of the Chinese Communist Youth League posted a full copy of women’s rights under Chinese law, finally adding: “Netizens should maintain rationality, post positively, and not give online violence a chance to flourish.”

By Cat Hanson

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Cat Hanson is a U.K. graduate of Chinese Studies now teaching and living in China. She swapped Beijing for Anhui, and runs her own blog on China life: Putong Press.

Also Read

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Zibo had its BBQ moment. Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine with its special take on malatang. Tourism marketing in China will never be the same again.

Published

3 weeks agoon

April 1, 2024

Since the early post-pandemic days, Chinese cities have stepped up their game to attract more tourists. The dynamics of Chinese social media make it possible for smaller, lesser-known destinations to gain overnight fame as a ‘celebrity city.’ Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine.

During this Qingming Festival holiday, there is one Chinese city that will definitely welcome more visitors than usual. Tianshui, the second largest city in Gansu Province, has emerged as the latest travel hotspot among domestic tourists following its recent surge in popularity online.

Situated approximately halfway along the Lanzhou-Xi’an rail line, this ancient city wasn’t previously a top destination for tourists. Most travelers would typically pass through the industrial city to see the Maiji Shan Grottoes, the fourth largest Buddhist cave complex in China, renowned for its famous rock carvings along the Silk Road.

But now, there is another reason to visit Tianshui: malatang.

Gansu-Style Malatang

Málàtàng (麻辣烫), which literally means ‘numb spicy hot,’ is a popular Chinese street food dish featuring a diverse array of ingredients cooked in a soup base infused with Sichuan pepper and dried chili pepper. There are multiple ways to enjoy malatang.

When dining at smaller street stalls, it’s common to find a selection of skewered foods—ranging from meats to quail eggs and vegetables—simmering in a large vat of flavorful spicy broth. This communal dining experience is affordable and convenient for solo diners or smaller groups seeking a hotpot-style meal.

In malatang restaurants, patrons can usually choose from a selection of self-serve skewered ingredients. You have them weighed, pay, and then have it prepared and served in a bowl with a preferred soup base, often with the option to choose the level of spiciness, from super hot to mild.

Although malatang originated in Sichuan, it is now common all over China. What makes Tianshui malatang stand out is its “Gansu-style” take, with a special focus on hand-pulled noodles, potato, and spicy oil.

An important ingredient for the soup base is the somewhat sweet and fragrant Gangu chili, produced in Tianshui’s Gangu County, known as “the hometown of peppers.”

Another ingredient is Maiji peppercorns (used in the sauce), and there are more locally produced ingredients, such as the black fungi from Qingshui County.

One restaurant that made Tianshui’s malatang particularly famous is Haiying Malatang (海英麻辣烫) in the city’s Qinzhou District. On February 13, the tiny restaurant, which has been around for three decades, welcomed an online influencer (@一杯梁白开) who posted about her visit.

The vlogger was so enthusiastic about her taste of “Gansu-style malatang,” that she urged her followers to try it out. It was the start of something much bigger than she could have imagined.

Replicating Zibo

Tianshui isn’t the first city to capture the spotlight on Chinese social media. Cities such as Zibo and Harbin have previously surged in popularity, becoming overnight sensations on platforms like Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin.

This phenomenon of Chinese cities transforming into hot travel destinations due to social media frenzy became particularly noteworthy in early 2023.

During the Covid years, various factors sparked a friendly competition among Chinese cities, each competing to attract the most visitors and to promote their city in the best way possible.

The Covid pandemic had diverse impacts on the Chinese domestic tourism industry. On one hand, domestic tourism flourished due to the pandemic, as Chinese travelers opted for destinations closer to home amid travel restrictions. On the other hand, the zero-Covid policy, with its lockdowns and the absence of foreign visitors, posed significant challenges to the tourism sector.

Following the abolition of the zero-Covid policy, tourism and marketing departments across China swung into action to revitalize their local economy. China’s social media platforms became battlegrounds to capture the attention of Chinese netizens. Local government officials dressed up in traditional outfits and created original videos to convince tourists to visit their hometowns.

Zibo was the first city to become an absolute social media sensation in the post-Covid era. The old industrial and mining city was not exactly known as a trendy tourist destination, but saw its hotel bookings going up 800% in 2023 compared to pre-Covid year 2019. Among others factors contributing to its success, the city’s online marketing campaign and how it turned its local BBQ culture into a unique selling point were both critical.

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Since 2023, multiple cities have tried to replicate the success of Zibo. Although not all have achieved similar results, Harbin has done very well by becoming a meme-worthy tourist attraction earlier in 2024, emphasizing its snow spectacle and friendly local culture.

By promoting its distinctive take on malatang, Tianshui has emerged as the next city to captivate online audiences, leading to a surge in visitor numbers.

Like with Zibo and Harbin, one particular important strategy used by these tourist offices is to swiftly respond to content created by travel bloggers or food vloggers about their cities, boosting the online attention and immediately seizing the opportunity to turn online success into offline visits.

A Timeline

What does it take to become a Chinese ‘celebrity city’? Since late February and early March of this year, various Douyin accounts started posting about Tianshui and its malatang.

They initially were the main reason driving tourists to the city to try out malatang, but they were not the only reason – city marketing and state media coverage also played a role in how the success of Tianshui played out.

Here’s a timeline of how its (online) frenzy unfolded:

- July 25, 2023: First video on Douyin about Tianshui’s malatang, after which 45 more videos by various accounts followed in the following six months.

- Feb 5, 2024: Douyin account ‘Chuanshuo Zhong de Bozi’ (传说中的波仔) posts a video about malatang streetfood in Gansu

- Feb 13, 2024: Douyin account ‘Yibei Liangbaikai’ (一杯梁白开) posts a video suggesting the “nationwide popularization of Gansu-style malatang.” This video is an important breakthrough moment in the success of Tianshui as a malatang city.

- Feb – March ~, 2024: The Tianshui Culture & Tourism Bureau is visiting sites, conducting research, and organizing meetings with different departments to establish the “Tianshui city + malatang” brand (文旅+天水麻辣烫”品牌) as the city’s new “business card.”

- March 11, 2024: Tianshui city launches a dedicated ‘spicy and hot’ bus line to cater to visitors who want to quickly reach the city’s renowned malatang spots.

- March 13-14, 2024: China’s Baidu search engine witnesses exponential growth in online searches for Tianshui malatang.

- March 14-15, 2024: The boss of Tianshui’s popular Haiying restaurant goes viral after videos show him overwhelmed and worried he can’t keep up. His facial expression becomes a meme, with netizens dubbing it the “can’t keep up-expression” (“烫不完表情”).

The worried and stressed expression of this malatang diner boss went viral overnight.

- March 17, 2024: Chinese media report about free ‘Tianshui malatang’ wifi being offered to visitors as a special service while they’re standing in line at malatang restaurants.

- March 18, 2024: Tianshui opens its first ‘Malatang Street’ where about 40 stalls sell malatang.

- March 18, 2024: Chinese local media report that one Tianshui hair salon (Tony) has changed its shop into a malatang shop overnight, showing just how big the hype has become.

- March 21, 2024: A dedicated ‘Tianshui malatang’ train started riding from Lanzhou West Station to Tianshui (#天水麻辣烫专列开行#).

- March 21, 2024: Chinese actor Jia Nailiang (贾乃亮) makes a video about having Tianshui malatang, further adding to its online success.

- March 30, 2024: A rare occurrence: as the main attraction near Tianshui, the Maiji Mountain Scenic Area announces that they’ve reached the maximum number of visitors and don’t have the capacity to welcome any more visitors, suspending all ticket sales for the day.

- April 1, 2024: Chinese presenter Zhang Dada was spotted making malatang in a local Tianshui restaurant, drawing in even more crowds.

A New Moment to Shine

Fame attracts criticism, and that also holds true for China’s ‘celebrity cities.’

Some argue that Tianshui’s malatang is overrated, considering the richness of Gansu cuisine, which offers much more than just malatang alone.

When Zibo reached hype status, it also faced scrutiny, with some commenters suggesting that the popularity of Zibo BBQ was a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and “empty social spectacle.”

There is a lot to say about the downsides of suddenly becoming a ‘celebrity city’ and the superficiality and fleetingness that comes with these kinds of trends. But for many locals, it is seen as an important moment as they see their businesses and cities thrive.

Even after the hype fades, local businesses can maintain their success by branding themselves as previously viral restaurants. When I visited Zibo a few months after its initial buzz, many once-popular spots marketed themselves as ‘wanghong’ (网红) or viral celebrity restaurants.

For the city itself, being in the spotlight holds its own value in the long run. Even after the hype has peaked and subsided, the gained national recognition ensures that these “trendy” places will continue to attract visitors in the future.

According to data from Ctrip, Tianshui experienced a 40% increase in tourism spending since March (specifically from March 1st to March 16th). State media reports claim that the city saw 2.3 million visitors in the first three weeks of March, with total tourism revenue reaching nearly 1.4 billion yuan ($193.7 million).

There are more ripple effects of Tianshui’s success: Maiji Shan Grottoes are witnessing a surge in visitors, and local e-commerce companies are experiencing a spike in orders from outside the city. Even when they’re not in Tianshui, people still want a piece of Tianshui.

By now, it’s clear that tourism marketing in China will never be the same again. Zibo, Harbin, and Tianshui exemplify a new era of destination hype, requiring a unique selling point, social media success, strong city marketing, and a friendly and fair business culture at the grassroots level.

While Zibo’s success was largely organic, Harbin’s was more orchestrated, and Tianshui learned from both. Now, other potential ‘celebrity’ cities are preparing to go viral, learning from the successes and failures of their predecessors to shine when their time comes.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

In Hot Water: The Nongfu Spring Controversy Explained

Nongfu and nationalists: how the praise for one Chinese domestic water bottle brand sparked online animosity toward another.

Published

1 month agoon

March 14, 2024

PREMIUM CONTENT

The big battle over bottled water has taken over Chinese social media recently. The support for the Chinese Wahaha brand has morphed into an anti-Nongfu Spring campaign, led by online nationalists.

Recently, China’s number one water brand, Nongfu Spring (农夫山泉) has found itself in the midst of an online nationalist storm.

The controversy started with the passing of Zong Qinghou (宗庆后), the founder and chairman of Wahaha Group (娃哈哈集团), the largest beverage producer in China. News of his passing made headlines on February 25, 2024, with one Weibo hashtag announcing his death receiving over 900 million views (#宗庆后逝世#).

The death of the businessman led to an outpouring of emotions on Weibo, where netizens praised his work ethic, dedication, and unwavering commitment to his principles.

Zong Qinghou, image via Weibo.

Born in 1945, Zong established Wahaha in Hangzhou in 1987, starting from scratch alongside two others. Despite humble beginnings, Zong, who came from a poor background, initially sold ice cream and soft drinks from his tricycle. However, by the second year, the company achieved success by concentrating on selling nutritional drinks to children, a strategy that resonated with Chinese single-child families (Tsui et al., 2017, p. 295).

The company experienced explosive growth and, boasting over 150 products ranging from milk drinks to fruit juices and soda pops, emerged as a dominant force in China’s beverage industry and the largest domestic bottled-water company.

Big bottle of Wahaha (meaning “laughing child”) water.

The admiration for Zong Qinghou and his company relates to multiple factors. Zong was loved for his inspirational rags-to-riches story under China’s economic reform, not unlike the self-made Tao Huabi and her Laoganma brand.

He was also loved for establishing a top Chinese national brand and refusing to be bought out. A decade after Wahaha partnered with the France-based multinational Danone in 1996, the two companies clashed when Zong accused Danone of trying to take over the Wahaha brand, which turned into a high-profile legal battle that was eventually settled in 2009, when Danone eventually sold all its stakes.

It is one of the reasons why Zong was known as a “patriotic private entrepreneur” (爱国民营企业家) who remained devoted to China and his roots.

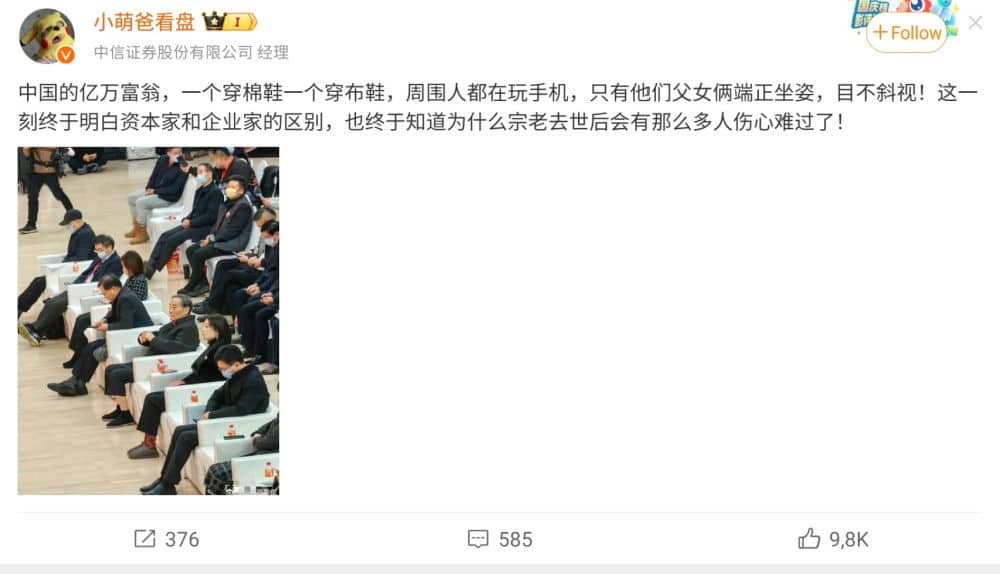

Netizens also admire the Chinese tycoon’s modesty and humility despite his immense wealth. He would often wear simple cloth shoes and, apparently not caring much about the elite social stratum, allegedly declined invitations to dine with Bill Gates and the Queen of England. He had a people-centric business approach. He prioritized the welfare of Wahaha employees, ensuring the protection of pensions for retired workers, establishing an employee stock ownership plan, and refused to terminate employees older than 45.

A post praising Zong and his daughter for staying humble despite their wealth: wearing simple shoes and not looking at their phones.

Zong and his daughter stand out due to their simple shoes.

As a tribute to Zong following his passing in late February, people not only started buying Wahaha bottled water, they also initiated criticism against its major competitor, Nongfu Spring (农夫山泉). Posts across various Chinese social media platforms, from Douyin to Weibo, started to advocate for boycotting Nongfu as a means to “protect” Wahaha as a national, proudly made-in-China brand.

From Love for Wahaha to Hate for Nongfu

With the death of Zong Qinghou, it seems that the decades-long rivalry between Nongfu and Wahaha has suddenly taken center stage in the public opinion arena, and it’s clear who people are rooting for.

The founder and chairman of Nongfu Spring is Chinese entrepreneur Zhong Shanshan (钟睒睒), and he is perhaps less likeable than Zong Qinghou, in part because he is not considered as patriotic as him.

Born in 1954, Zhong Shanshan is a former journalist who started working for Wahaha in the early 1990s. He established his own company and started focusing on bottled water in 1996. He would become China’s richest man.

His wealth was not just accumulated because of his Nongfu Spring water, which would become a leader in China’s bottled water market. Zhong also became the largest shareholder of Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise, which experienced significant growth following its IPO. Cecolin, a vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV), is manufactured by Innovax, a wholly owned subsidiary of Wantai.

Zhong Shanshan, image via Sohu.

The fact that Zhong Shanshan previously worked for Zong Qinghou and later ventured out on his own does not cast him in a positive light, especially in the context of netizens mourning Zong. Many people perceive Zhong Shanshan as a profit-driven businessman who lacks humility and national spirit compared to his former boss. Some even label him as ‘ungrateful.’

By now, the support for Wahaha water has snowballed into an anti-Nongfu campaign, resulting in intense scrutiny and criticism directed at the brand and its owner. This has led to a significant boycott and a sharp decline in sales.

Netizens are finding multiple reasons to attack Nongfu Spring and its owner. Apart from accusing Zhong Shanshan of being ungrateful, one of the Nongfu brand’s product packaging designs has also sparked controversy. The packaging of its Oriental Leaf Green Tea has been alleged to show Japanese elements, leading to claims of Zhong being “pro-Japan.”

Chinese social media users claim the packaging of this green tea is based on Japanese architecture instead of Chinese buildings.

Another point of ongoing contention is the fact that Zhong’s son (his heir, Zhong Shuzi 钟墅子) holds American citizenship. This has sparked anger among netizens who question Zhong’s allegiance to China. Concerned that the future of Nongfu might be in the US instead of China, they accuse Zhong and his business of betraying the Chinese people and being unpatriotic.

But what also plays a role in this, is how Zhong and the Nongfu Spring PR team have responded to the ongoing criticism. Some bloggers (link, link) argue their approach lacks emotional connection and comes off as too business-like.

On March 3rd, Zhong himself issued a statement addressing the personal attacks he faced following the passing of Zong Qinghou. In his article (我与宗老二三事), he aimed to ‘set the record straight.’ Although he expressed admiration for Zong Qinghou, many found his piece to be impersonal and more focused on safeguarding his own image.

The same criticism goes for the company’s response to the “pro-Japan” issue. On March 7, they refuted ongoing accusations and stated that the architecture depicted on the controversial beverage packaging was inspired by Chinese temples, not Japanese ones, and that a text on the bottle is about Japanese tea culture originating from China.

Calls for Calmer Water

Although Weibo and other social media platforms in China have recently seen a surge in nationalism, not everybody agrees with the way Nongfu Spring is being attacked. Some say that netizens are taking it too far and that a vocal minority is controlling the trending narrative.

Posts or videos from people pouring out Nongfu water in their sink are countered by others from people saying that they are now buying the brand to show solidarity in the midst of the social media storm.

Online photo of netizen buying Nongfu Spring water: “I support Nongfu Spring, I support private entrepreneurs, I support the recovery of China’s economy. I firmly opposo populism running wild.”

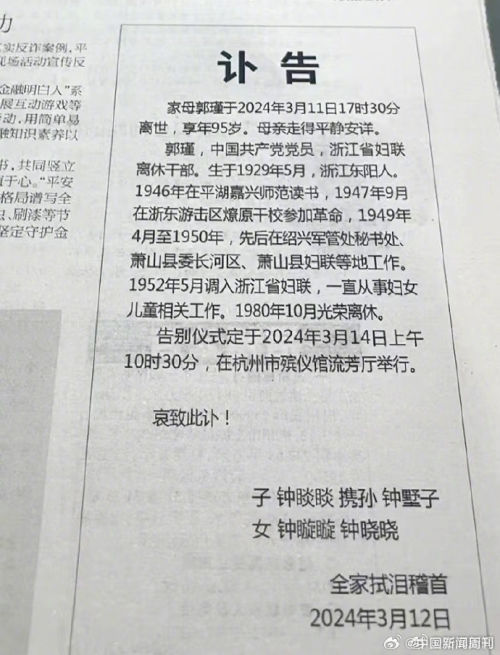

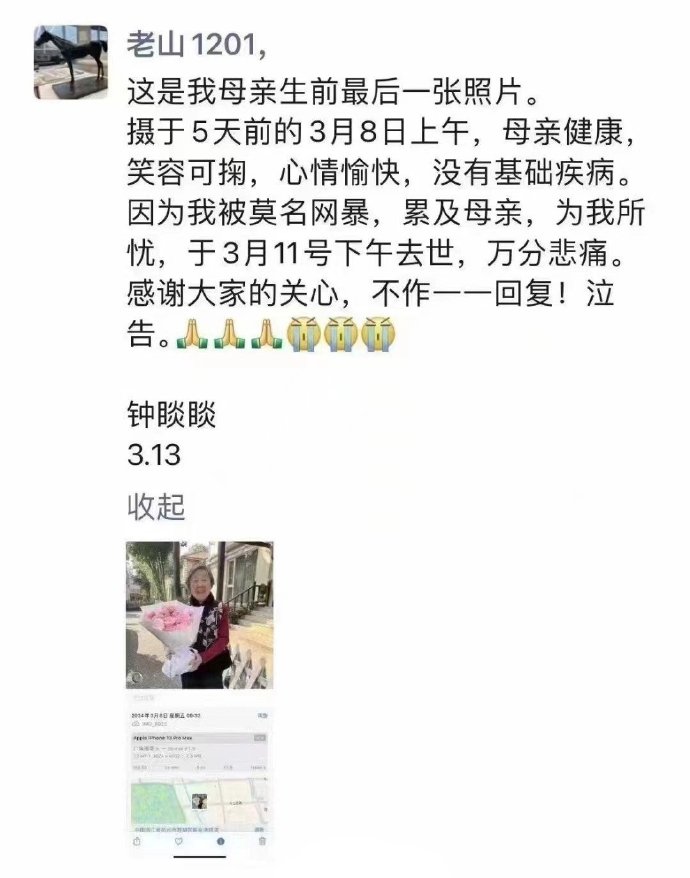

While more people are speaking out against the recent waves of nationalism, news came in on March 13 that the 95-year-old mother of Zhong Shanshan had passed away. According to an obituary published in the Qianjiang Evening News newspaper, Guo Jin (郭瑾) passed away on March 11.

The obituary.

A screenshot of a WeChat post alleged to be written by Zhong Shanshan made its rounds, in which Zhong blamed the online hate he received, and the ensuing stress, for his mother’s death.

While criticism of Zhong resurfaced for attributing the old lady’s death to “indescribable cyberbullying” (“莫名网暴”), some saw this moment as an opportunity to bring an end to the attacks on Nongfu. As the controversy continued to brew, the Sina Weibo platform seemingly attempted to divert attention by removing some hashtags related to the issue (e.g., “Zhong Shanshan’s Mother Guo Jin Passed Away” #钟睒睒之母郭瑾离世#).

The well-known Chinese commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) also spoke out in support of Nongfu Spring and called for rationality, arguing that Chinese private entrepreneurs are facing excessive scrutiny. He suggested that China’s netizens should stop nitpicking over their private matters and instead focus more on their contributions to the country’s economy.

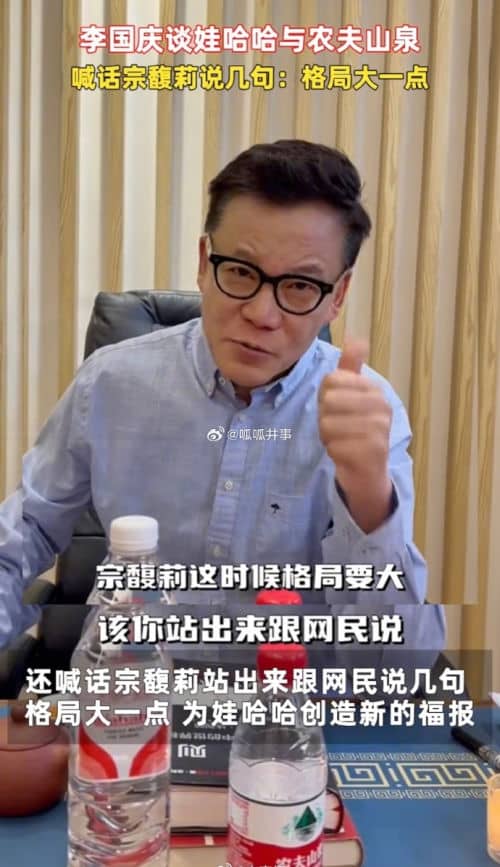

Others are also calling for an end to the waves of attacks towards Nongfu and Zhong Shanshan. Chinese entrepreneur Li Guoqing (李国庆), co-founder of the e-commerce company Dangdang (once hailed as the ‘Amazon of China’), posted a video about the issue on March 12. He said: “These two [Nongfu Spring and Wahaha brands] have come a long way to get to where they are today. The fact that they are competitors is a good thing. If old Zong [Qinghou] were still alive today and saw this division, he would surely step forward and tell people to get back to business and rational competition.”

Li Guoqing in his video (since deleted).

Li also suggested that Zong’s heir, his daughter Kelly Zong, should come out, broaden her perspective, and settle the matter. She should thank netizens for their support, he argued, and tell them that it is completely unnecessary to exacerbate the rift with Nongfu Spring in showing their support.

But those mingling in the matter soon discover themselves how easy it is to get your fingers burned on this hot topic. Li Guoqing might have meant well, but he also faced attacks after his video. Not only because people feel he is putting Kelly Zong in an awkward position, but also because his own son. like Zhong Shuzi, allegedly holds American citizenship. Perhaps unwilling to find himself in hot water as well, Li Guoqing has since deleted his video. The Nongfu storm may be one that should blow over by itself.

By Manya Koetse

With contributions by Miranda Barnes

References

Tsui, Anne S., Yingying Zhang, Xiao-Ping Chen. 2017. “Chinese Companies Need Strong and Open-minded Leaders. Interview with Wahaha Group Founder, Chairman and CEO, Qinghou Zong.” In Leadership of Chinese Private Enterprises

Insights and Interviews, Palgrave MacMillan.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

Weibo Watch: Burning BMWs

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

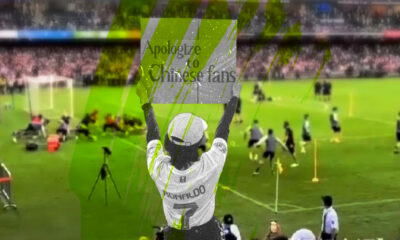

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

In Hot Water: The Nongfu Spring Controversy Explained

The Benz Guy from Baoding and the Granny Xu Line-Cutting Controversy

Weibo Watch: Stealing the Show

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment2 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment2 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Media1 month ago

China Media1 month agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

-

China World2 months ago

China World2 months agoFrom Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)