China Health & Science

The “Last Downer”: China and the End of Down Syndrome

With screenings for Down syndrome becoming more advanced, there are less and less babies being born with Down in China every year. Unborn babies with Down syndrome are allowed to be aborted to up to nine months of pregnancy.

Published

8 years agoon

New screenings that can predict if an unborn baby has Down syndrome have sparked wide debate across the world – mostly because their results often lead to parents choosing for abortion. The ethical debate that is so alive in many countries seems practically non-existent in China, where Down syndrome is slowly disappearing from society. Unborn babies with Down syndrome are allowed to be aborted to up to the ninth month of pregnancy; 21% of Down-related abortions in China occur during or after the seventh month.

Last month was World Down Dyndrome Day (世界唐氏综合征日, March 21) and next month marks China’s National Disability Day (全国助残日, May 15) – both are occasions when Chinese media pay extra attention to Down syndrome, a disorder that is slowly disappearing from Chinese society.

On World Down Syndrome Day, Chinese state media broadcaster CCTV wrote on its Weibo account: “Currently, medical science does not have effective prevention and treatment methods for Down syndrome, but it can be detected early through prenatal screening. You might have seen this kind of face: mouth slightly open, a blank expression, eyes somewhat wide apart,.. break your prejudices and understand them!” This text is accompanied by different facts about Down syndrome pictured with a cartoon baby on CCTV’s account page (pictured below).

“I’m still nervously awaiting the results of the amniotic fluid test,” one netizen responds to the post: “I hope my baby is healthy and normal.”

On Chinese social media, many expecting mothers express their worries about screening results and the health of their unborn child. But the ethical debate that is so alive in many other countries about Down syndrome screening and abortion seems practically non-existent in China. One Weibo user comments: “In foreign countries, there are many mothers raising kids with Down, because their religion does not allow them to abort the baby.”

THE “LAST DOWNER”

“New medical techniques and the ethical questions that come with it have caused ample discussion on Down syndrome in many nations across the world.”

Down syndrome (DS) is a congenital disorder caused by a chromosome defect, that exists in all regions worldwide. Children with DS often have an intellectual disability and are also affected physically in their appearance and general health. Down syndrome has an incidence of 1 in 600–1000 live births, differing per country (UN; Wang et al 2013, 273). The disorder was named after John Langdon Down, the British physician who first classified this genetic disorder in 1862. In Chinese, it is known as 唐氏综合征 (Tángshì zònghézhēng) or as 先天愚型 (Xiāntiān yúxíng), the latter literally meaning ‘naturally stupid-type’.

With new techniques, it has become easier for doctors to safely detect whether or not a fetus has Down syndrome. In many countries, women can now choose for first-trimester prenatal screenings that can indicate the likelihood they are carrying a baby with Down syndrome. These tests can be followed up with diagnostic tests, either through amniocentesis (amniotic fluid test) or a DNA blood test, that can give a conclusive answer. If the unborn baby turns out to have DS, parents often have the option to abort it.

These new medical techniques and the ethical questions that come with them have caused ample discussions on Down syndrome in many nations across the world. Denmark introduced national guidelines for prenatal screening and diagnosis as early as 2004, which has led to an all-time low of Danish infants with Down syndrome – 95%-98% of pregnant women choose to abort a fetus with DS (Vice 2015). This means that Down could become something of the past; not just in Denmark, but also in other countries that have followed its example after 2004.

According to anti-abortion media, what is happening in Denmark is a “targeted form of genocide.” In the United States, the test has also become a focus of controversy, as it is intertwined with America’s general debate over abortion.

The Dutch TV-series “The Last Downer” (sic) explored the gradual disappearance of Down Syndrome. The show was co-hosted by two young adults who were born with DS themselves. Photo via NPO/NRC of TV Show “De Laatste Downer.”

In the Netherlands, a TV show revolving around ‘the end of Down syndrome’ was recently aired on national television. The series, that was titled ‘The Last Downer’, explored what society loses if Down syndrome disappears. It also talked about the ethical, social and psychological consequences of having a child with Down syndrome. ‘The Last Downer’ also triggered debate, as some critics deemed that it was too much in favor of the pro-life movement.

DOWN SYNDROME IN CHINA

“21% of abortions related to DS in China take place after the 28th week of pregnancy.”

In China, it is estimated that 1 out of 700 infants are affected with Down syndrome. Although this percentage is relatively low compared to other countries, it is an enormous figure nevertheless due to China’s huge population (Deng et al 2015, 311).

China’s Ministry of Health has promoted nationwide prenatal screenings for birth defects since 2003 (312). As pointed out in recent Chinese research, there has since been a sharp increase in the percentage of prenatal diagnosis and consequential birth termination (Deng et al 2015, 315).

The detection of Down syndrome through prenatal diagnosis in China went from nearly 13% in 2003 to over 69% in 2011 – with urban women having better access to early screenings and diagnosis than women living in the more rural areas of China. Around 95% of women terminate their pregnancy after learning the baby has DS, which is close to similarly high numbers in countries like Denmark or Hungary.

What is different in China, is that abortions can take place up to the ninth month of pregnancy.* In nearly 80% of the cases where the DS diagnosis led to abortion, this termination took place before 28 weeks. In the other cases, the pregnancy was terminated later than 28 weeks; meaning that 21% of abortions related to DS take place after the 28th week of pregnancy (ibid. 2015, 315).** In, for example, the Netherlands, abortion can take place up to 24 weeks of pregnancy, which is determined as the moment after which a fetus would be able to survive outside the uterus. Denmark allows for abortions to take place until the 12th week of pregnancy.

Chinese doctors encourage screening more strongly when pregnant women are older. According to current regulations in China, pregnant women aged 35 or above will be suggested to have an amniocentesis test directly, and, as research points out, “most Chinese women opt to abort fetuses with malformations” (Deng et al 2015, 316). Overall, the prevalence of prenatal diagnosis of DS and the number of related abortions is higher in urban areas than in China’s rural areas due to better medical facilities in cities. This also suggests that the majority of babies with DS are now born in the countryside, where parents do not always have access to the medical care they need.

ABORTION IS OKAY

“Bright-pink advertisements on ‘painless abortions’ depict smiling women, butterflies and flowers.”

On Weibo, many netizens share their experiences with prenatal screening. One pregnant woman says the test has cost her 191 RMB (±30 US$), another netizen responds: “In my hometown, these screenings are free of charge!” Another Weibo user shares her anxiousness: “I’ve been worrying about this Down screening all week,” she writes on April 21st. The following day, she replies to the comments with crying emoticons.

Although the screenings are a big issue on Chinese social media, the ethical question of the abortions is seemingly not. This might relate to the fact that abortion is not as contentious in China as it is in many other countries.

Pregnancy termination became quite common in China during the 20th century in relation to the one-child policy. By now, China has the highest abortion rate in the world. According to the National Health and Family Planning Commission, 13 million abortions are carried out in China every year. The actual number is probably much higher, as the official number does not include the abortion numbers from private clinics, nor the estimated 10 million induced abortions per year through medicine (Xinhua 2014), nor the numbers of sex-selective abortions– a practice that has officially been illegal since 2004.

The prevalence of abortions in China has led to a booming industry focused on abortion procedures. Bright-pink advertisements on ‘painless abortions’ depict smiling women, butterflies and flowers.

Some even promise that the abortion will be over within ‘a dreamlike three minutes’ (for more on this read: Glamorous & Painless – China’s Booming Abortion Industry). Although China has a painful past when it comes to forced abortions, the personal choice for abortion is not as controversial as it is in many countries where the Down syndrome detection debate is more alive.

“I’m drinking fresh rosedew after my abortion,” one netizen writes: “It’s good for my cold womb.”

THE HARDSHIPS OF DOWN CHILDREN IN CHINA

“Giving a child with Down syndrome up for adoption is very difficult, as China’s DS children are generally deemed ‘unadoptable’.”

Besides the fact that abortion is considered relatively uncontroversial in China, the high rate of abortions for DS-diagnosed babies might also relate to the fact that disabled children face many difficulties in China due to stigmatization and practical hurdles.

Raising a handicapped child is a heavy burden for many parents in China, who receive little government support and often do not have the means to make sure their child gets the medical care and education they need. This means that abandoning the child sometimes is the only solution for parents to make sure their child is taken into an institution (Yoxall 2008, 25).

Giving a child with Down syndrome up for adoption is very difficult, as China’s DS children are generally deemed ‘unadoptable‘. Until recently, it was legally not possible to adopt a child with Down within China. Since this has now changed, international organizations like the Bamboo Project help parents who want to adopt a child with Down syndrome from China.

SCREENINGS FOR DOWN: ANXIETY & CONFUSION

“If your baby has Down syndrome, you can’t keep it – you do understand this, don’t you?”

In China’s urban areas, first-trimester screenings for DS (唐氏筛查) through a blood test have become practically mandatory. Some clinics have 100% screening guidelines for all of their patients, but do ask parents to sign for consent first; other hospitals simply proceed to include the test with general pregnancy check-ups without any permission.

Screening procedures differ per hospital and can be confusing for expecting mothers: “Today my doctor told me that because I am already 35, I should do an amniocentesis test,” one netizen writes on Weibo: “but the blood test in my first trimester indicated I had low risk of having a baby with Down. I’m very confused if I should do it or not.”

China’s screening procedures and prevalent attitudes on how to deal with a baby that possibly has DS can be shocking to some. A 31-year-old Dutch mum named Anna (alias), who lives in Shanghai, recently shared her experiences on Facebook. Anna, pregnant with her second baby, writes:

“I was unable to come on Facebook for some time due to problems with my VPN. During this period, I’ve come across something that I loathe even more than China’s internet censorship. “They’ve tried calling you but you didn’t pick up,” the Chinese nurse tells me while looking up from a form, as she points me to an examination room. I walk in, and ask the doctor what’s going on – I vaguely remember a ‘standard’ blood test (..) – “‘You have an increased risk for a child with a mental disability,’ the doctor straightforwardly tells me. ‘Excuse me?’ – I ask her to repeat her sentence. ‘The child might be retarded,’ she tells me.”

Anna writes: “In the Netherlands, the availability of prenatal tests for Down syndrome has caused quite some controversy earlier this year. It is not allowed for doctors to proactively encourage women to do this test unless there’s an increased risk for them to have a child with an intellectual disability – because they are above the age of 40, for example. But this is not the case in China, where every pregnant woman, no matter her age, is tested for heightened risk through blood screening. I ask the doctor what the test results are, since I’m only 31. ‘Well, that’s not like being 21 anymore, now it is?’ she snarls at me.”

Anna explains that the results of her blood test showed there was a 1-in-200 chance her baby had Down syndrome. After informing Anna about this, the doctor says: “You can choose if you now want an amniocentesis or a DNA test. The first is more expensive and needs to be done in a private clinic, here’s an information leaflet, just think about it.”

She chooses to do the DNA test, which is safer for mothers and their unborn babies than the amniocentesis. She says: “I was initially just shocked to hear there was an increased risk for me to have a child with a disorder, but it also bothered me that the initial screening was done without my consent. I ask the doctor what happens if my baby turns out to have Down syndrome. ‘Then you can’t keep it,’ she gives me a piercing look: ‘You do understand this, don’t you?’”

Anna writes: “She advised me to timely book a possible abortion, but that the procedure would be possible until 32 (!) weeks.” Anna receives the DNA test results a week later through text message, and her baby shows no signs of abnormalities. Despite her relief, she feels uncomfortable about the intrusive way in which her prenatal screening and its possible outcome was handled.

Another foreigner living in Beijing told What’s on Weibo they also were tested for Down syndrome risks in the first trimester of pregnancy at Beijing United hospital without being asked for permission first. Although they were surprised to get the results, they did not react strongly to it as the test turned out to be very low risk.

Although the ethical debate on this issue is generally lacking from mainstream media, one story did make headlines last year when a woman from Hubei was determined to end her pregnancy at 16 weeks because of the Down syndrome screening. The initial blood screenings showed an increased risk of DS, and the woman arranged an abortion – in spite of the doctors convincing her that she should wait for the actual diagnoses screening first. This story also shows how intertwined prenatal screenings and abortion have become.

DS IN CHINA: TABOOS AND SOCIAL STIGMA

“I think my sister’s baby has Down syndrome, but I am too afraid to ask her.”

Chinese netizens share their experience with Down syndrome on various online message boards. One netizen tells how it is growing up with a brother with Down syndrome. “My brother was born prematurely and was in weak health. The doctor told my parents to just give up on him. But my father refused to give up, because it was a boy, and he thinks boys are worth more than girls. So my brother lived.” The netizen tells how his parents were told by doctors that their child was simply “hopeless”, and that his brother was always teased in school.

On message board Douban, multiple netizens share how doctors encourage couples to have an abortion if their unborn baby is diagnosed with DS. The discussion of Down on Chinese social media shows that DS is heavily stigmatized and that it is sometimes also considered a taboo. Some netizens tell about former classmates with Down who were constantly bullied, and one netizen writes: “I think my sister’s baby has Down syndrome, but I am too afraid to ask her.”

Now that rapidly advancing medical techniques have decreased the prevalence of DS in China, chances are that the less common the disorder is, the more stigmatized it will become. It is also probable that over the next one or two decades, if rural areas get better access to medical care, Down syndrome will altogether disappear from China.

For China’s upcoming ‘day for the handicapped’, multiple organizations try to raise more public awareness for Down syndrome. This year, the day will specifically focus on handicapped orphans. For this occasion Chinese media recently wrote about an orphanage in Tianjin, where one-third of all children are Down syndrome babies who were left behind by their parents.

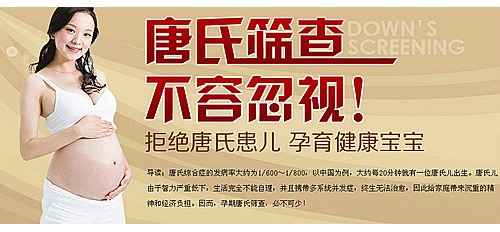

Although the article describes children with DS as little “happy angels”, one Chinese birth clinic seems to think otherwise. In their ad (see image), their message is loud and clear: “Reject children with Down syndrome! Give birth to a healthy baby!” Angels or not, modern-day China seems to have no place for Down syndrome children.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

[rp4wp]

References

Wang, S.-S., Wang, C., Qiao, F.-Y., Lv, J.-J. & Feng, L. 2013. “Polymorphisms in genes RFC-1/CBS as maternal risk factors for Down syndrome in China.” Arch Gyneocol Obstet 288: 273-277.

Deng, C., Yi, L., Mu, Y., Zhu, J., Qin, Y., Fan, X., Li, Q. & Dai, L. 2015. “Recent trends in the birth prevalence of Down syndrome in China: impact of prenatal diagnosis and subsequent terminations.” Prenatal Diagnosis, 35(4), 311–318.

Yoxal, James W. 2008. China’s Social Policy: Meeting the Needs of Orphaned and Disabled Children. Master Thesis, Union Institute & University.

NB: other references are linked to in-text.

* As written by Deng et al (2015): “Following a systemic and standardized diagnostic process, pregnancy affected by severe anomalies such as DS is allowed to be terminated at any gestational age following informed consent” (312).

** According to 2003-2011 surveillance data, study by Deng et al uses data from the Chinese Birth Defects Monitoring Network.

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Food & Drinks

Chinese Woman with Heartbreak Passes Away after Drinking Bottle of Baijiu

Three friends are held partially responsible for not intervening when the woman consumed 500ml of baijiu.

Published

4 months agoon

December 15, 2023

An incident that happened on the night of May 21, 2023, has become a trending topic on Chinese social media today after a local court examined the case.

A woman named ‘Xiao Qiu’ (alias), a resident of Jiangxi’s Nanchang, apparently attempted to drink her sorrows away after a heartbreaking breakup.

She spent the night at a friend’s house, where she drank about 50cl of baijiu (白酒), a popular Chinese spirit distilled from fermented sorghum that contains between 35% and 60% alcohol. One entire bottle of baijiu, such as Moutai, is usually 50cl.

She was together with three female friends. One of them also consumed baijiu, although not as much, and the two other friends did not drink at all.

As reported by Jiupai News, the intoxicated Xiao Qu ended up sleeping in her car, while one of her sober friends stayed with her. However, at about 5 AM, her friend discovered that Xiao Qiu was no longer breathing. Just about an hour later, she was declared dead at the local Emergency Center. The cause of death was ruled as cardiac and respiratory failure due to alcohol poisoning.

The court found that Xiao Qu’s friends were partly responsible for her death, citing their failure to prevent her excessive drinking and inadequate assistance following her baijiu binge drink session. Each friend was directed to contribute to the compensation for medical expenses and pain and suffering incurred by Qiu’s family.

The friend who also consumed baijiu was assigned a 6% compensation responsibility, while the other two were assigned 3% each.

On Weibo, many commenters do not agree with the court’s decision, asserting that adult individuals should not be held accountable when a friend goes on a drinking spree. Some commenters wrote: “You can tell someone not to drink, but what if they don’t listen?” “Should we record ourselves telling friends not to drink too much from now on?”

This is not the first time for friends to be held liable for an alcohol-related death in China. In 2018, multiple stories went viral involving people who died after excessive drinking at social gatherings.

One case involved a 30-year-old Chinese man who was found dead in his hotel room bathtub in Yangzhou after a formal dinner with friends where he allegedly drank heavily. The man reportedly died of a heart attack. His friends reached a 1 million yuan (±US$157,000) settlement with his family, with the cost shared among the friends who were present during the night.

Surveillance cameras in Jinhua captured how the man was unable to stand or walk after drinking with his friends.

Another case involved a man who died when he was left by his friends at a hotel in Jinhua, Zhejiang province, after heavily drinking at a banquet. Surveillance cameras captured how the man was unable to stand or walk after drinking with his friends. Those friends also paid a compensation together of 610,000 yuan (US$96,000) to the man’s family.

Organisers of an alcohol drinking contest in Henan province were also ordered to pay a compensation of over US$70,000 after one participant died due to excessive alcohol intake in July of 2017.

These cases also triggered online discussions about how Chinese traditional drinking culture often encourages people at the table to drink as much as they can or to exceed their limits; the goal sometimes is to literally “take someone to the ground by drinking.” When someone proposes a toast, everyone at the table is required to finish their glasses, sometimes at a very high pace.

In light of the latest news, some commenters write on Weibo: “No matter what kind of drinking gathering it is, for someone who is already drunk, others should intervene to prevent them from continuing to drink. Even if they invite, provoke, or insist on drinking themselves, they should not be allowed to continue. Otherwise, it not only harms them, you might end up facing legal responsibility yourself.”

Others remind people that overindulging in alcohol when you’re in a state of distress is never a good idea, and that no heartbreak is worth getting drunk over: “There are plenty of other fish in the sea.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Health & Science

‘Sister Blood Points’ Controversy: Shanghai Woman’s Tibet Blood Donations Ignite Privilege Debate

Dozens of local public officials in Tibet donated blood to rescue a Shanghainese woman. Netizens believe it’s a matter of privilege.

Published

4 months agoon

December 9, 2023

The medical rescue of a critically injured Shanghai woman in Tibet has recently triggered major controversy on Chinese social media after netizens suspected that the woman’s treatment may have been facilitated through the abuse of power.

What was supposed to be a romantic honeymoon getaway turned into a nightmare for newlyweds Yu Yanyan (27, 余言言) and her husband Tao Li (29, 陶立).

On October 14, just two weeks after their wedding, the couple from Shanghai was driving on China’s National Highway 219. Their destination was Ngari Prefecture in Tibet’s far west, where the average elevation is 4500 meters.

As they drove by the famous mountain pass Jieshan Daban (界山達阪), situated at an altitude of 5347 meters, they suddenly realized that the altitude was affecting them. Soon, Tao Li, who was driving the car, lost consciousness and crashed the car. Yu Yanyan, on the passenger side, was badly injured in the crash.

The crashed car, image via Beijing News/Xinjinbao (source).

What followed was a complicated, time-sensitive, and costly rescue operation. At the Ngari People’s Hospital (阿里地区人民医院), Yu was diagnosed with a ruptured liver, abdominal bleeding, hemorrhagic shock, and thoracic trauma. She was losing a lot of blood in a short time and required surgery, but there was not enough blood available for a blood transfusion at the time in the sparsely populated region, as reported by Beijing News.

Tibetan Civil Servants to the Rescue

While the hospital made efforts to secure donations, specifically requiring an adequate supply of A+ type blood, Yu’s husband was reportedly advised to reach out to the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (上海卫健委) to inquire about potential assistance. One of his aunts, or his ‘auntie’, allegedly helped him to contact them.

These efforts appeared to be fruitful. Between October 16-17, just days following the crash, numerous members of the public and dozens of local civil servants in Tibet, including firefighters, policemen, and military personnel, stepped forward to donate blood, contributing to over 7000 mL of A-type Rh-positive blood that ultimately saved Yu’s life.

Allegedly thanks to the Tibet office of the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government, a medical specialist from Shanghai was even sent to assist in the medical treatment of Yu at the Ngari hospital.

As Yu later required more advanced medical care and surgeries, she was advised to go to a bigger hospital. She was then transferred via a specially arranged chartered plane. The total costs of this medical chartered plane flight from Ngari to Sichuan’s Huaxi hospital (四川华西医院), arranged by Yu’s father, allegedly cost 1,2 million yuan (US$169.230).

After receiving surgery at the Huaxi Hospital, Yu was in stable condition and was transferred to Shanghai.

An Abuse of Power?

Yu’s story began drawing notice, eventually garnering nationwide media coverage, after Yu herself posted a video on her social media account (Douyin) in which she recounted her experiences. Yu, who only had a relatively small group of followers, told about her rescue operation and her recovery. But instead of garnering sympathy, it led to many questions from netizens and went viral. The video was later deleted.

Screenshots from the since deleted Douyin video.

Who was the ‘auntie’ who reached out to the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission? How were Tibet public officials made to donate blood for this Shanghai patient? What power dynamics were in play that facilitated the mobilization of people in this manner by the family?

People became upset, as they suspected Yu’s life had only been saved because of an abuse of power, and that ordinary Chinese patients would never have never received a similar treatment.

They started referring to Yu as ‘Sister Blood Points.’ The Chinese term is xuè cáo jiě 血槽姐, with xuè cáo 血槽 (lit. blood groove) often being used in the world of gaming to refer to the health bar, an image in video games that shows the player how much energy or blood or strength they have left before it’s game over.

Various online AI-generated images featuring a portrayal of “Sister Blood Points.”

There were also various digital (AI-generated) images showing Yu surrounded by bags of donated blood, portraying her as a privileged, blood-sucking Shanghai ‘princess’ in Tibet.

Following the online commotion, the Ngari Propaganda Department issued a statement on November 29 promising to look into the issue. Additionally, in the first week of December, various Chinese media outlets also started to investigate the case.

An Ordinary Patient in Extraordinary Circumstances

On December 6, online newspaper The Paper (澎湃新闻) published an article together with Shangguan News (上观新闻) which answered some of the most pressing questions surrounding the case.

The Paper reported that they found no officially organized mobilization of public officials or members of the public to donate blood. Instead, local workers and individuals donated blood after learning about the woman’s situation through various channels, including from the hospital staff. Yu Yanyan’s husband Tao called the successful blood donation campaign a result of “multi-party mobilization” (“这是我们多方动员的结果,确实不是有组织的。”)

The Shanghai Municipal Health Commission also denied that they had contacted health authorities in Tibet to ask civil servants to donate blood. They claimed their members of staff did not personally know the patient nor any members of her or her husband’s family.

Furthermore, the article says that the woman known as ‘auntie’ is a 60-year-old retired woman who previously worked at a crafts factory. Upon learning about Yu’s predicament, she forwarded the information to her daughter-in-law, who works at a bank and also did all she could to spread the news and ask for help. This eventually led to the Tibet office of the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government being updated on the situation.

The Tibet office has refuted any suggestion that personal relationships influenced the procedures that resulted in the dispatch of a Shanghai medical expert to assist at Ngari People’s Hospital. A Shanghai medical team stationed in Tibet received a request for urgent support at the hospital and, following their ethical work guidelines, dispatched an expert to provide assistance.

The Paper further stated that nor Yu, nor her husband or their family were officials. In order to pay for the medical flight, Yu’s parents used family savings and borrowed money from others.

All of the information that was coming out about the entire ordeal seemed to indicate that Yu was just an ordinary patient in extraordinary circumstances.

A Sign of Distrust

While certain commenters believe that the latest information has put an end to weeks of speculation, others continue to harbor suspicions that there might be more to the story – they are not satisfied with the answers provided on December 6.

As some netizens dug up screenshots of online calls for help from Tao, Yu’s husband, some commenters responded: “This only makes it clearer that there’s no special status (特殊身份) here. Real influential officials wouldn’t go so low as to seek help online. A simple phone call would have quickly resolved their issue.”

In the end, the entire ordeal, now labeled “The Civil Servant Blood Donation Incident” (公务员献血事件) on Chinese social media, reveals more about public distrust in the transparency of China’s healthcare system than it does about Yu, her family, or the situation in Tibet.

While frustrations regarding privilege and power abuse within China’s healthcare system have existed for years, this issue has gained significant public attention this year in light of the launch of a top-down anti-corruption campaign targeting the healthcare industry.

This issue is especially important due to China’s longstanding struggle with public mistrust in the medical care sector. Some studies even suggest that China’s healthcare system has suffered from a “trust crisis among the public” since the 1990s (Chen & Cheng 2022, 2).

Multiple factors contribute to the relatively low trust in the Chinese healthcare system, but access and costs both play major roles. The sentence “Getting medical attention is difficult, getting medical attention is expensive” (Kànbìng nán, kànbìng guì 看病难,看病贵) has become a well-known expression among Chinese patients dissatisfied with the challenges they encounter in both accessibility and affordability when seeking medical treatments.

Most medical providers in China have become increasingly commercialized and profit-driven since the 1980s, leading to problems with crime and corruption within the medical system as medical professionals are expected to balance both a focus on patient well-being and financial gain. With doctors contending with low pay and incentive-based labor, bribery has emerged as a well-known problem, often considered somewhat of an “open secret” (Fun & Yao 2017, 30-31).

The prevalence of such issues has fueled public frustration, making individual cases like Yu Yanyan’s a source of intense controversy. In an environment where “getting medical attention is difficult, getting medical attention is expensive,” and where corruption is a notorious problem, many people simply do not think it is possible for one young woman to receive so much medical assistance from doctors and civil servants without the involvement of connections, power abuse, and bribery in the process.

Now that more details about the ‘blood point sister’ story have come to light, most netizens have started to question the truth behind this story and realize that Yu might just be an ordinary citizen, while some bloggers are still demanding more answers. In the end, most agree that it is not really about Miss Yu at all, but about whether or not they could expect similar medical treatment if they would end up in such a terrible situation.

“Is there currently an emergency response system in place that allows ordinary people to seek help in equally urgent crises?” (“当前是否存在一个紧急响应机制,可以让普通人在遇到同样紧急的危机时,能寻求帮助?”) one Sina blogger wonders.

“It is actually not important to know if they had special privileges or not,” one Weibo commenter writes: “I just hope that if patients need donated blood in the future, they will get the same treatment.”

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References:

Chen, Lu, and Miaoting Cheng. 2022. “Exploring Chinese Elderly’s Trust in the Healthcare System: Empirical Evidence from a Population-Based Survey in China.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (24): 16461-.

Fun, Yujing & Zelin Yao. 2017. “A State of Contradiction: Medical Corruption and Strain in Beijing Public Hospitals. In: Børge Bakken (Ed.), Crime and the Chinese Dream, Hong Kong University Press: 20–39.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

Weibo Watch: Burning BMWs

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

A Snowball Effect: How Cold Harbin Became the Hottest Place in China

Jia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Weibo Watch: Frogs in Wells

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight1 month ago

China Insight1 month agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoA Snowball Effect: How Cold Harbin Became the Hottest Place in China

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoJia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

-

China Arts & Entertainment2 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment2 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Colette

July 18, 2016 at 1:02 am

In the UK termination for DS is also permitted until 9 months………Lord Shinkwin is trying to change this.

jack

October 27, 2016 at 3:40 am

The truth is the chinese and the Japanese are a mongoloid race they were created from the daughters of a man called Lot the nephew of abraham in the bible read the story of Sodom and gomorrah this will tell of Lots two daughters and there plan…the modern day chinese are the moabites and the Japanese are the modern day ammonites,incest causes down syndrome or retardation these two nations are the product of incest…BASTARD babies…truth is hard to accept

Anonymous

December 27, 2016 at 6:11 am

Please go back to /pol/.