China Health & Science

One Man’s Battle to Make China Smoke-free

Although the Chinese government is implementing more measures to counter smoking, the country is estimated to have more than 300 million smokers. Zhang Yue, “China’s First Anti-Smoking Campaigner” (“中国第一反烟人”) is determined to single-handedly pull the cigarettes out of their mouths and make China smoke-free.

Published

8 years agoon

Although the Chinese government is implementing more measures to counter smoking, the country is estimated to have more than 300 million smokers. Zhang Yue, “China’s First Anti-Smoking Campaigner” (“中国第一反烟人”) is determined to single-handedly pull the cigarettes out of their mouths and make China smoke-free.

Zhang Yue (张跃) is no ordinary person. The self-proclaimed “top anti-smoking fighter” has been campaigning for a smoke-free China for over 18 years . On his publicity tours, that took him to more than 386 cities, he creates awareness for the dangers of smoking.

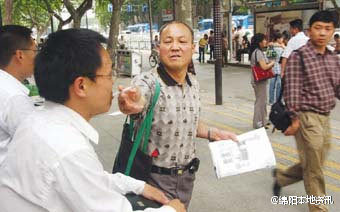

Global Times reports how Zhang usually starts these trips by visiting crowded places like bus stops, metro stations or markets, where he strikes up a conversation with smokers and hands them pamphlets about the risks of smoking. He then shocks smokers by pulling the cigarette from their lips. He sometimes does this to over ten people within thirty minutes.

Zhang surprises a smoker by grabbing the cigarette from his mouth (Phoenix News).

Zhang surprises a smoker by grabbing the cigarette from his mouth (Phoenix News).

Zhang’s crusade against smoking and his confrontational methods have popped up in Chinese media since 2003 (see China Daily).

Zhang started his no-smoking mission after the tragic death of his sister, who died of a brain tumor at the age of 26. Zhang was convinced that his father’s heavy smoking habits played a role in his sister’s death, as she had always been in good health prior to her tumor. After successfully helping his younger brother quit smoking, Zhang also persuaded twelve of his family members to stop smoking. Since 2001, he has devoted his life to help all smokers of China to quit their habit.

A money-making national pastime

Smoking is a national pastime in China. It is very common for Chinese men to offer a cigarette when meeting someone – it’s a conversation starter and a way of social bonding. Over time, smoking has become an integral part of how many Chinese men socialize.

Apart from the social aspect, the popularity of smoking is also linked to economics. China is the largest manufacturer and consumer of tobacco in the world. The country employs a massive labor force devoted to tobacco farming, manufacturing and sales. Tobacco sales also provide 7% of the Central Government’s annual revenue, which is a substantial amount in taxes and net income.

A gendered phenomenon that kills

According to the authors of a new study, reported about by Quartz, “about two-thirds of young Chinese men become cigarette smokers, and most start before they are 20. Unless they stop, about half of them will eventually be killed by their habit.”

The study notes that although many women have begun taking to smoking, it still remains a highly gendered activity, with around 68% of Chinese men smoking, compared to 3.2 % of Chinese women. Another study by the National Center for Biotechnology Information in the United States has reported that with a population of over 300 million smokers, China is currently at risk of losing more than 90 million people to this habit. This is also a reason for concern as smoking threatens to wipe out the productive population that China increasingly needs to continue its growth momentum.

The Party’s new anti-smoking route

After repeated attempts and failings, the Party has started to take the problem of smoking more serious. Although China’s previous leaders were often seen smoking, Xi Jinping has set a new example by quitting.

In 2011, China’s Ministry of Health guidelines banned smoking in all public places nationwide such as hotels and restaurants. As the ban was largely ignored, stricter regulations went into effect in Beijing in June 2015. These regulations also cracked down on tobacco advertising.

The Party’s new anti-smoking route was also apparent during the National People’s Congress meeting this year; different from other years, there were no smoking areas for delegates in their hotel and conference rooms, or elsewhere in the indoor public places. They had been advised to follow Beijing’s smoking ban during the two-week annual session .

But for Zhang Yue, the Party’s anti-smoking campaigns cannot be rigorous enough and he hopes that China will soon be completely smoke-free: “China has 350 million smokers,” he tells Global Times: “that’s almost the population of the US. Even though it’s a distant goal, I’ll sacrifice everything to get there”.

Right motives, wrong behavior?

News about Zhang’s mission and his action to pull cigarettes from people’s mouths has got Weibo’s netizens talking. “His motives are good, but his actions are stupid,” one netizen comments. “He has no right to steal people’s cigarettes,” another Weibo user says.

Although most netizens seem to disagree with Zhang’s tactics, some think he’s right: “I support him. I’ve smoked for over ten years and then just quit. I wished more people would.”

Zhang’s campaign goes beyond the streets of China – he is also active on Chinese social media. On Weibo, Zhang has an official Weibo page named ‘The Old Man’s Long March Against Smoking‘. With less than 8900 online fans, he does not have the millions of followers he would probably like to have – but at least it’s a start.

Update March 23 by editor: Shortly after this article was published, the Weibo account of “The Old Man’s Long March Against Smoking” (“反烟人长征愚公”的微博) disappeared, which is why the link is no longer working.

– By Mahalakshmi Ganapathy

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Images by Phoenix News and Mianyang Local News Weibo Page.

Weibo comments & editing by Manya Koetse.

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

About the author: Mahalakshmi Ganapathy is a Shanghai-based Sinologist-to-be, pursuing her graduate degree in Chinese Politics at East China Normal University. Her interests include Sino-India comparative studies and Chinese political philosophy.

Also Read

China Food & Drinks

Chinese Woman with Heartbreak Passes Away after Drinking Bottle of Baijiu

Three friends are held partially responsible for not intervening when the woman consumed 500ml of baijiu.

Published

4 months agoon

December 15, 2023

An incident that happened on the night of May 21, 2023, has become a trending topic on Chinese social media today after a local court examined the case.

A woman named ‘Xiao Qiu’ (alias), a resident of Jiangxi’s Nanchang, apparently attempted to drink her sorrows away after a heartbreaking breakup.

She spent the night at a friend’s house, where she drank about 50cl of baijiu (白酒), a popular Chinese spirit distilled from fermented sorghum that contains between 35% and 60% alcohol. One entire bottle of baijiu, such as Moutai, is usually 50cl.

She was together with three female friends. One of them also consumed baijiu, although not as much, and the two other friends did not drink at all.

As reported by Jiupai News, the intoxicated Xiao Qu ended up sleeping in her car, while one of her sober friends stayed with her. However, at about 5 AM, her friend discovered that Xiao Qiu was no longer breathing. Just about an hour later, she was declared dead at the local Emergency Center. The cause of death was ruled as cardiac and respiratory failure due to alcohol poisoning.

The court found that Xiao Qu’s friends were partly responsible for her death, citing their failure to prevent her excessive drinking and inadequate assistance following her baijiu binge drink session. Each friend was directed to contribute to the compensation for medical expenses and pain and suffering incurred by Qiu’s family.

The friend who also consumed baijiu was assigned a 6% compensation responsibility, while the other two were assigned 3% each.

On Weibo, many commenters do not agree with the court’s decision, asserting that adult individuals should not be held accountable when a friend goes on a drinking spree. Some commenters wrote: “You can tell someone not to drink, but what if they don’t listen?” “Should we record ourselves telling friends not to drink too much from now on?”

This is not the first time for friends to be held liable for an alcohol-related death in China. In 2018, multiple stories went viral involving people who died after excessive drinking at social gatherings.

One case involved a 30-year-old Chinese man who was found dead in his hotel room bathtub in Yangzhou after a formal dinner with friends where he allegedly drank heavily. The man reportedly died of a heart attack. His friends reached a 1 million yuan (±US$157,000) settlement with his family, with the cost shared among the friends who were present during the night.

Surveillance cameras in Jinhua captured how the man was unable to stand or walk after drinking with his friends.

Another case involved a man who died when he was left by his friends at a hotel in Jinhua, Zhejiang province, after heavily drinking at a banquet. Surveillance cameras captured how the man was unable to stand or walk after drinking with his friends. Those friends also paid a compensation together of 610,000 yuan (US$96,000) to the man’s family.

Organisers of an alcohol drinking contest in Henan province were also ordered to pay a compensation of over US$70,000 after one participant died due to excessive alcohol intake in July of 2017.

These cases also triggered online discussions about how Chinese traditional drinking culture often encourages people at the table to drink as much as they can or to exceed their limits; the goal sometimes is to literally “take someone to the ground by drinking.” When someone proposes a toast, everyone at the table is required to finish their glasses, sometimes at a very high pace.

In light of the latest news, some commenters write on Weibo: “No matter what kind of drinking gathering it is, for someone who is already drunk, others should intervene to prevent them from continuing to drink. Even if they invite, provoke, or insist on drinking themselves, they should not be allowed to continue. Otherwise, it not only harms them, you might end up facing legal responsibility yourself.”

Others remind people that overindulging in alcohol when you’re in a state of distress is never a good idea, and that no heartbreak is worth getting drunk over: “There are plenty of other fish in the sea.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Health & Science

‘Sister Blood Points’ Controversy: Shanghai Woman’s Tibet Blood Donations Ignite Privilege Debate

Dozens of local public officials in Tibet donated blood to rescue a Shanghainese woman. Netizens believe it’s a matter of privilege.

Published

5 months agoon

December 9, 2023

The medical rescue of a critically injured Shanghai woman in Tibet has recently triggered major controversy on Chinese social media after netizens suspected that the woman’s treatment may have been facilitated through the abuse of power.

What was supposed to be a romantic honeymoon getaway turned into a nightmare for newlyweds Yu Yanyan (27, 余言言) and her husband Tao Li (29, 陶立).

On October 14, just two weeks after their wedding, the couple from Shanghai was driving on China’s National Highway 219. Their destination was Ngari Prefecture in Tibet’s far west, where the average elevation is 4500 meters.

As they drove by the famous mountain pass Jieshan Daban (界山達阪), situated at an altitude of 5347 meters, they suddenly realized that the altitude was affecting them. Soon, Tao Li, who was driving the car, lost consciousness and crashed the car. Yu Yanyan, on the passenger side, was badly injured in the crash.

The crashed car, image via Beijing News/Xinjinbao (source).

What followed was a complicated, time-sensitive, and costly rescue operation. At the Ngari People’s Hospital (阿里地区人民医院), Yu was diagnosed with a ruptured liver, abdominal bleeding, hemorrhagic shock, and thoracic trauma. She was losing a lot of blood in a short time and required surgery, but there was not enough blood available for a blood transfusion at the time in the sparsely populated region, as reported by Beijing News.

Tibetan Civil Servants to the Rescue

While the hospital made efforts to secure donations, specifically requiring an adequate supply of A+ type blood, Yu’s husband was reportedly advised to reach out to the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (上海卫健委) to inquire about potential assistance. One of his aunts, or his ‘auntie’, allegedly helped him to contact them.

These efforts appeared to be fruitful. Between October 16-17, just days following the crash, numerous members of the public and dozens of local civil servants in Tibet, including firefighters, policemen, and military personnel, stepped forward to donate blood, contributing to over 7000 mL of A-type Rh-positive blood that ultimately saved Yu’s life.

Allegedly thanks to the Tibet office of the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government, a medical specialist from Shanghai was even sent to assist in the medical treatment of Yu at the Ngari hospital.

As Yu later required more advanced medical care and surgeries, she was advised to go to a bigger hospital. She was then transferred via a specially arranged chartered plane. The total costs of this medical chartered plane flight from Ngari to Sichuan’s Huaxi hospital (四川华西医院), arranged by Yu’s father, allegedly cost 1,2 million yuan (US$169.230).

After receiving surgery at the Huaxi Hospital, Yu was in stable condition and was transferred to Shanghai.

An Abuse of Power?

Yu’s story began drawing notice, eventually garnering nationwide media coverage, after Yu herself posted a video on her social media account (Douyin) in which she recounted her experiences. Yu, who only had a relatively small group of followers, told about her rescue operation and her recovery. But instead of garnering sympathy, it led to many questions from netizens and went viral. The video was later deleted.

Screenshots from the since deleted Douyin video.

Who was the ‘auntie’ who reached out to the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission? How were Tibet public officials made to donate blood for this Shanghai patient? What power dynamics were in play that facilitated the mobilization of people in this manner by the family?

People became upset, as they suspected Yu’s life had only been saved because of an abuse of power, and that ordinary Chinese patients would never have never received a similar treatment.

They started referring to Yu as ‘Sister Blood Points.’ The Chinese term is xuè cáo jiě 血槽姐, with xuè cáo 血槽 (lit. blood groove) often being used in the world of gaming to refer to the health bar, an image in video games that shows the player how much energy or blood or strength they have left before it’s game over.

Various online AI-generated images featuring a portrayal of “Sister Blood Points.”

There were also various digital (AI-generated) images showing Yu surrounded by bags of donated blood, portraying her as a privileged, blood-sucking Shanghai ‘princess’ in Tibet.

Following the online commotion, the Ngari Propaganda Department issued a statement on November 29 promising to look into the issue. Additionally, in the first week of December, various Chinese media outlets also started to investigate the case.

An Ordinary Patient in Extraordinary Circumstances

On December 6, online newspaper The Paper (澎湃新闻) published an article together with Shangguan News (上观新闻) which answered some of the most pressing questions surrounding the case.

The Paper reported that they found no officially organized mobilization of public officials or members of the public to donate blood. Instead, local workers and individuals donated blood after learning about the woman’s situation through various channels, including from the hospital staff. Yu Yanyan’s husband Tao called the successful blood donation campaign a result of “multi-party mobilization” (“这是我们多方动员的结果,确实不是有组织的。”)

The Shanghai Municipal Health Commission also denied that they had contacted health authorities in Tibet to ask civil servants to donate blood. They claimed their members of staff did not personally know the patient nor any members of her or her husband’s family.

Furthermore, the article says that the woman known as ‘auntie’ is a 60-year-old retired woman who previously worked at a crafts factory. Upon learning about Yu’s predicament, she forwarded the information to her daughter-in-law, who works at a bank and also did all she could to spread the news and ask for help. This eventually led to the Tibet office of the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government being updated on the situation.

The Tibet office has refuted any suggestion that personal relationships influenced the procedures that resulted in the dispatch of a Shanghai medical expert to assist at Ngari People’s Hospital. A Shanghai medical team stationed in Tibet received a request for urgent support at the hospital and, following their ethical work guidelines, dispatched an expert to provide assistance.

The Paper further stated that nor Yu, nor her husband or their family were officials. In order to pay for the medical flight, Yu’s parents used family savings and borrowed money from others.

All of the information that was coming out about the entire ordeal seemed to indicate that Yu was just an ordinary patient in extraordinary circumstances.

A Sign of Distrust

While certain commenters believe that the latest information has put an end to weeks of speculation, others continue to harbor suspicions that there might be more to the story – they are not satisfied with the answers provided on December 6.

As some netizens dug up screenshots of online calls for help from Tao, Yu’s husband, some commenters responded: “This only makes it clearer that there’s no special status (特殊身份) here. Real influential officials wouldn’t go so low as to seek help online. A simple phone call would have quickly resolved their issue.”

In the end, the entire ordeal, now labeled “The Civil Servant Blood Donation Incident” (公务员献血事件) on Chinese social media, reveals more about public distrust in the transparency of China’s healthcare system than it does about Yu, her family, or the situation in Tibet.

While frustrations regarding privilege and power abuse within China’s healthcare system have existed for years, this issue has gained significant public attention this year in light of the launch of a top-down anti-corruption campaign targeting the healthcare industry.

This issue is especially important due to China’s longstanding struggle with public mistrust in the medical care sector. Some studies even suggest that China’s healthcare system has suffered from a “trust crisis among the public” since the 1990s (Chen & Cheng 2022, 2).

Multiple factors contribute to the relatively low trust in the Chinese healthcare system, but access and costs both play major roles. The sentence “Getting medical attention is difficult, getting medical attention is expensive” (Kànbìng nán, kànbìng guì 看病难,看病贵) has become a well-known expression among Chinese patients dissatisfied with the challenges they encounter in both accessibility and affordability when seeking medical treatments.

Most medical providers in China have become increasingly commercialized and profit-driven since the 1980s, leading to problems with crime and corruption within the medical system as medical professionals are expected to balance both a focus on patient well-being and financial gain. With doctors contending with low pay and incentive-based labor, bribery has emerged as a well-known problem, often considered somewhat of an “open secret” (Fun & Yao 2017, 30-31).

The prevalence of such issues has fueled public frustration, making individual cases like Yu Yanyan’s a source of intense controversy. In an environment where “getting medical attention is difficult, getting medical attention is expensive,” and where corruption is a notorious problem, many people simply do not think it is possible for one young woman to receive so much medical assistance from doctors and civil servants without the involvement of connections, power abuse, and bribery in the process.

Now that more details about the ‘blood point sister’ story have come to light, most netizens have started to question the truth behind this story and realize that Yu might just be an ordinary citizen, while some bloggers are still demanding more answers. In the end, most agree that it is not really about Miss Yu at all, but about whether or not they could expect similar medical treatment if they would end up in such a terrible situation.

“Is there currently an emergency response system in place that allows ordinary people to seek help in equally urgent crises?” (“当前是否存在一个紧急响应机制,可以让普通人在遇到同样紧急的危机时,能寻求帮助?”) one Sina blogger wonders.

“It is actually not important to know if they had special privileges or not,” one Weibo commenter writes: “I just hope that if patients need donated blood in the future, they will get the same treatment.”

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References:

Chen, Lu, and Miaoting Cheng. 2022. “Exploring Chinese Elderly’s Trust in the Healthcare System: Empirical Evidence from a Population-Based Survey in China.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (24): 16461-.

Fun, Yujing & Zelin Yao. 2017. “A State of Contradiction: Medical Corruption and Strain in Beijing Public Hospitals. In: Børge Bakken (Ed.), Crime and the Chinese Dream, Hong Kong University Press: 20–39.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

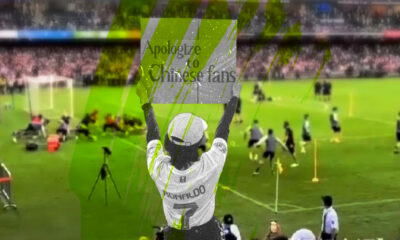

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

In Hot Water: The Nongfu Spring Controversy Explained

The Benz Guy from Baoding and the Granny Xu Line-Cutting Controversy

Weibo Watch: Stealing the Show

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Media1 month ago

China Media1 month agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

-

China World2 months ago

China World2 months agoFrom Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)