China Insight

Blazing Memories: About the Comparison of the Notre Dame Fire to the Burning of the Old Summer Palace (Op-Ed)

Understanding why the Yuan Ming Yuan went trending in China after the Notre Dame fire.

Published

5 years agoon

First published

A What’s on Weibo news article on Chinese online responses to the Notre Dame fire attracted very mixed reactions on English-language social media this week.

After the fire at the Notre Dame in Paris earlier this week, What’s on Weibo published an article describing Chinese online responses to the devastating blaze, and the ubiquitous comments that compared the destruction of the iconic French cathedral to the burning of the Chinese Old Summer Palace (Yuan Ming Yuan) in Beijing by the Anglo-French army in 1860.

There have been many reactions to this story on various social media platforms. From one side, there were those who questioned why we would even publish an article like that, suggesting that our position in covering this trend was biased. On the other side, there were those who jumped into the discussion, blaming Chinese for playing the victim and ignoring the destruction of old historical buildings or Mosques within their own country over recent years.

The reactions to this article and overall trend show the polarized stances on social issues and media in China, and how to cover them. Some suggested that it was not fair to write down the “negative social media opinions of a few Chinese commenters,” saying that it “reflected badly” on China overall, or that they were “irrelevant.”

Covering the voices of a few dozen ‘trolls’ and presenting them as an ‘overall sentiment’ is not what we do at What’s on Weibo.

Some people pointed out that the comparison of the Notre Dame blaze to the burning of the Old Summer Palace was not something that most Chinese agreed with. As also covered in our article, there were indeed many commenters, including historians and Key Opinion Leaders, who opposed to the Yuan Ming Yuan trend in light of the Notre Dame fire.

The fact of the matter still is that the Old Summer Palace became a massive topic of online debate following the Notre Dame fire. Ignoring such a trend in covering Weibo responses to the tragic Paris incident would be a huge blind spot problem.

Instead of condemning these Chinese online responses, ignoring they are there, or trivializing their relevance, it is perhaps more constructive to consider where they come from, and understanding that the history of the Old Summer Palace is still deeply ingrained in the collective memory of the Chinese people and nation.

Before further elaborating on this, let’s first go back to the trend itself.

From Notre Dame to Yuan Ming Yuan

As news of the catastrophic fire that engulfed the Notre Dame Cathedral (巴黎圣母院) in Paris on Monday made headlines across the world, the Old Summer Palace (Yuan Ming Yuan 圆明园) suddenly became a trending topic on Chinese social media.

Besides all the people who mourned the destruction of the historic cathedral, and those who posted photos of their previous visits to the scenic spot, there were many Chinese netizens who started addressing the plundering and burning down of the Yuan Ming Yuan (“Garden of Perfect Brightness”) in 1860, leading to the Notre Dame and the Old Summer Palace becoming top trending topics on Weibo at the same time.

As Notre Dame goes trending on Weibo, so does the Old Summer Palace (top 4 top trending).

On April 18, WeChat self-media account Fang Zhouzi (方舟子) wrote about the reaction: “On Chinese internet, a peculiar response started to emerge, as many people suddenly started remembering the burning of the Yuan Ming Yuan by the Anglo-French forces 159 years ago, and thereupon saying that the Notre Dame deserved to be burned.”

It is unclear who first drew a comparison between the Notre Dame and the Yuan Ming Yuan, but on April 16, actor Zhou Libo (周立波) wrote on Weibo that “compared to the Yuan Ming Yuan, the Notre Dame is just a garden.” A former editor at the Phoenix News Military Channel, Jin Hao (金昊), also published an article on WeChat titled “Mourning it, my ass! I’m pleased with the big fire at Notre Dame” (“哀悼个屁!巴黎圣母院大火,我很欣慰!”) (since deleted).

On other social media sites, such as Douban, people also started posting blogs with titles such as “the Notre Dame collapse makes me think of the Old Summer Palace” (“巴黎圣母院的倒塌让我想起了圆明园”).

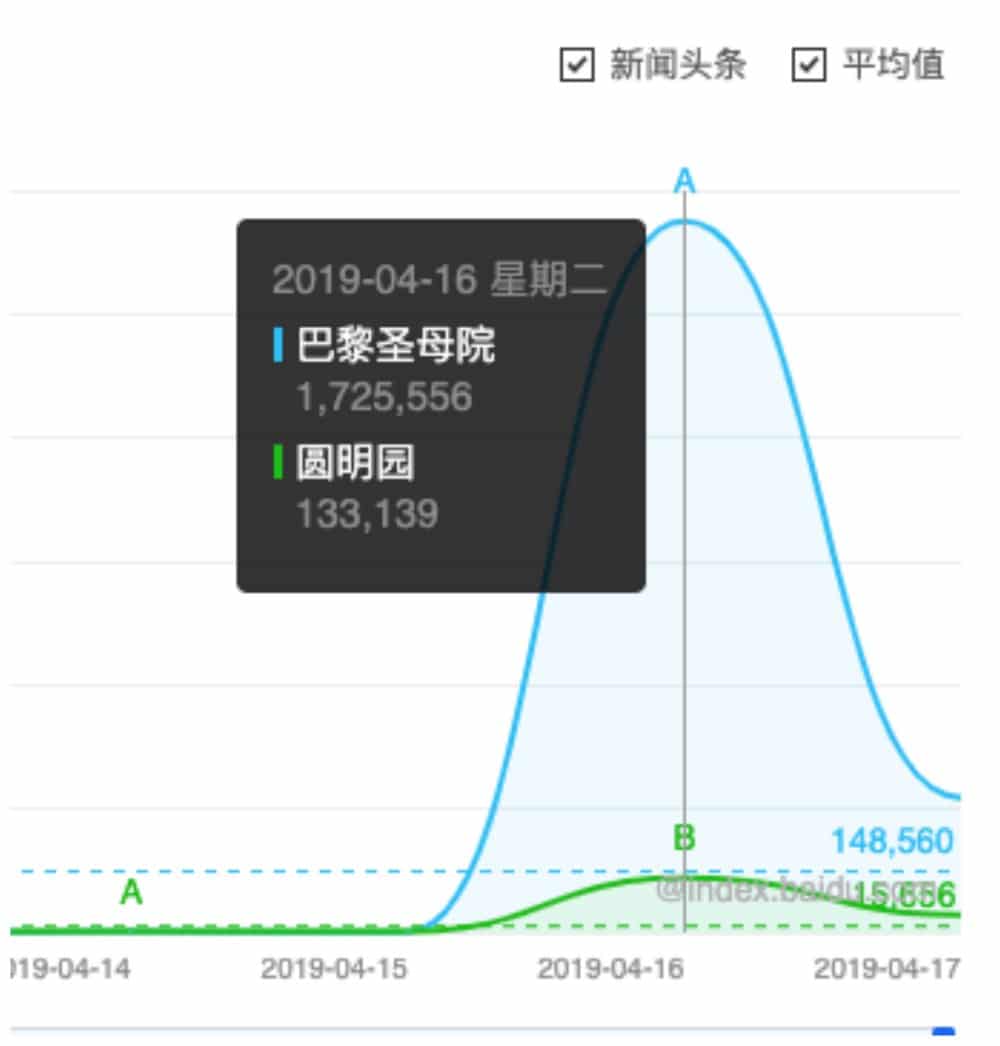

An exploration of search queries on Chinese search engine Baidu shows that at the time when ‘Notre Dame’ peaks as a query on April 16, so does the term ‘Yuan Ming Yuan.’ Similarly, on Google Trends, the Chinese query ‘Notre Dame’ shows the Yuan Ming Yuan Park as the number two related topic in its overview of the past week.

Baidu trends show that both the search terms ‘Notre Dame’ (A) and ‘Yuan Ming Yuan’ (B) simultaneously peak on April 16.

At time of writing, there are dozens of pages on Weibo filled with comments relating to the Notre Dame/Old Summer Palace comparison. We won’t list many of them here, but some of the comments include reactions such as: “Now you can also experience how it feels when art and culture are burned,” “I might have a narrow sense of patriotism, but seeing the Notre Dame burn makes me happy inside,” and “even a hundred Notre Dames still don’t make the Old Summer Palace,” with many netizens claiming that the loss of the Old Summer Palace was just as bad, or rather worse, than the destruction of the Notre Dame.

These collective responses to the Notre Dame fire also drew much criticism. State media outlet CCTV published an article that condemned the comparison of the Notre Dame and the Old Summer Palace, stating that people “should not vent their emotions in the name of history” (Li Xuefei 2019).

Various other news channels also published critique, including one article titled “The Notre Dame fire as retribution for the burning of Yuanmingyuan? Please stop this inhumane line of reasoning” (“巴黎圣母院大火是烧圆明园的报应?快停下反人类思维”).

As covered in our previous write-up, there were also many voices on Weibo denouncing the trend. One of them was Yan Feng (严锋), a professor at Fudan University, who posted:

“The Notre Dame cathedral was constructed in 1163, the Yuan Ming Yuan was destroyed in 1860. The people who burned the Yuan Ming Yuan were not the people who built the Notre Dame of Paris. They were separated by 700 years. The French feudal separatists were in no way French according to modern-day standards. Every injustice has its perpetrator and every debt its debtor, why should you let the Notre Dame bear the responsibility of burning down the Yuan Ming Yuan?”

“First of all, we are people, then we are Chinese,” another popular comment said: “The loss of such a historical cultural gem is a loss for all mankind.”

Collective Memories of Yuan Ming Yuan

In October of 1860, British and French troops sacked and burned the Old Summer Palace, which was once a massive complex consisting of more than a hundred buildings, pavilions, and scenic spots, built since the 17th century for the Qing emperors.

The event took place at the end of the Second Opium War. Unsatisfied with the Treaty of Nanjing and, among others, demanding more Chinese cities and ports to open for trade, the Anglo-French army invaded Beijing in 1860. They plundered the Yuan Ming Yuan, which was filled with books and art treasures. The burning came afterward, to destroy the evidence of their looting. The fire blazed for three days and three nights, leaving the enormous palace grounds in ruins (Chey 2009, 79).

The site of the once magnificent Old Summer Palace is now the Yuanmingyuan Ruins Park, an initiative that was set up in the 1980s after decades of neglect. In “The Ruins of Yuanmingyuan,” Haiyan Lee calls the site a “national wound” (2009). It is a symbolic space, where the ruins remind visitors of the injustice China once suffered at the hands of Western powers.

This injustice is an important incident in China’s so-called “Century of Humiliation,” the time from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s during which China was attacked, weakened, and torn by foreign forces.

The “Century of Humiliation” still plays an important role in China today, as young people are also taught that this historical consciousness is important. The four character slogan “Wù wàng guóchǐ” (勿忘国耻), “Never forget national humiliation”, is frequently repeated in Chinese media, museums, schools, documentaries, and in popular culture.

Young Chinese students carrying a sign “Never Forget National Humiliation”, image via Xinhua.

As described in the insightful work by Zheng Wang, Never Forget National Humiliation, the historical memory of China’s era of humiliation has become part of Chinese national identity, promoted in official discourse, and often unconsciously yet profoundly influencing people’s perceptions and actions. This is also what collective memory is: an accumulation of memory-forming processes that take place on both conscious and non-conscious levels (Koetse 2012, 10).

The Yuan Ming Yuan Park is a particularly significant cultural heritage site where the remembrance of the humiliations and injuries China suffered at the hands of foreign imperialists comes to life through the ruins (Lee 2008, 169).

Blazing Memories

Collective memory and nations are tied together in many ways, as historical memories serve as an important vehicle to unify the nation. They also play an important part in how people from different communities, societies, or nations will interpret big or important events that happen in the world today.

When certain news makes headlines, it is not uncommon for people to reflect on it speaking from their own experiences and the collective memory of their own nation or bigger community – especially when the place where it happens is far removed from them.

This is not unique to China. To grasp, process, and comment on faraway incidents, it is sometimes easier to relate it to something that is closer to you.

Former American first lady Michelle Obama visited Paris earlier this week for her book tour, and told the audience about how shocked she was about the Notre Dame blaze, briefly comparing the incident to the devastating American 9/11 attacks.* Does it make sense to compare the burning of the Notre Dame to the 9/11 attacks? Perhaps not. Yet Obama was not the only one to raise the 9/11 events; some on Twitter even called the burning of the Notre Dame “a cultural 9/11” disaster.

Seeing the overwhelming responses to the Notre Dame fire on Chinese social media, where so many people linked it to Chinese history, the reaction perhaps should not be whether these online responses and media discussions were either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ – instead, it is important to understand where they come from, and how people from various backgrounds, cultures, or religions, often use their own cultural or social frameworks, historical narratives, and dominating ideas to make sense of what is happening around them.

As the Notre Dame trend on Chinese social media shows, but what’s beyond the scope of this article, is that the mechanisms of online nationalism and anti-foreign sentiments often also come into play once these memory-machines start running.

In the end, the Notre Dame fire actually has nothing to do with the history of the Old Summer Palace. But the news of the Notre Dame blaze was enough reason for many Chinese netizens to trigger and bring up this memory of Chinese suffering that still exists in the minds of the people today.

Instead of condemning that, or trivializing news reports on these trends, one could try to understand it, and then see it as a completely separate issue from the Notre Dame fire – as many people on Weibo also do.

By Manya Koetse

Recommended reading:

References

Fang Zhouzi 方舟子. 2019. “巴黎圣母院和圆明园有什么关系?” April 18, Fang Zhouzi / Self-Media WeChat link[4.18.19].

Koetse, Manya. 2012. “The ‘Magic’ of Memory. Chinese and Japanese Re-Remembrances of the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945).” Research Master thesis, Leiden University.

Lee, Haiyuan. 2009. “The Ruins of Yuanmingyuan – Or, How to Enjoy a National Wound.” Modern China 35 (2): 155-190.

Li Xuefei 李雪菲. 2019. “巴黎圣母院火灾怎能与火烧圆明园混为一谈 狭隘的民族主义可休矣.” April 16, CCTV,Sina News https://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2019-04-16/doc-ihvhiqax3118848.shtml [4.18.19].

Ong, Siew Chey. 2009. China Condensed: 5, 000 Years of History & Culture. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International.

Weatherley, Robert D., and Ariane Rosen. 2013. “Fanning the Flames of Popular Nationalism: The Debate in China over the Burning of the Old Summer Palace.” Asian perspective 37(1):53-76.

Zheng Wang. 2012. Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations. New York: Columbia University Press.

* Segment on Michelle Obama in Paris from Dutch “Talkshow M” of April 17th, 36.00 min.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Zibo had its BBQ moment. Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine with its special take on malatang. Tourism marketing in China will never be the same again.

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 1, 2024

Since the early post-pandemic days, Chinese cities have stepped up their game to attract more tourists. The dynamics of Chinese social media make it possible for smaller, lesser-known destinations to gain overnight fame as a ‘celebrity city.’ Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine.

During this Qingming Festival holiday, there is one Chinese city that will definitely welcome more visitors than usual. Tianshui, the second largest city in Gansu Province, has emerged as the latest travel hotspot among domestic tourists following its recent surge in popularity online.

Situated approximately halfway along the Lanzhou-Xi’an rail line, this ancient city wasn’t previously a top destination for tourists. Most travelers would typically pass through the industrial city to see the Maiji Shan Grottoes, the fourth largest Buddhist cave complex in China, renowned for its famous rock carvings along the Silk Road.

But now, there is another reason to visit Tianshui: malatang.

Gansu-Style Malatang

Málàtàng (麻辣烫), which literally means ‘numb spicy hot,’ is a popular Chinese street food dish featuring a diverse array of ingredients cooked in a soup base infused with Sichuan pepper and dried chili pepper. There are multiple ways to enjoy malatang.

When dining at smaller street stalls, it’s common to find a selection of skewered foods—ranging from meats to quail eggs and vegetables—simmering in a large vat of flavorful spicy broth. This communal dining experience is affordable and convenient for solo diners or smaller groups seeking a hotpot-style meal.

In malatang restaurants, patrons can usually choose from a selection of self-serve skewered ingredients. You have them weighed, pay, and then have it prepared and served in a bowl with a preferred soup base, often with the option to choose the level of spiciness, from super hot to mild.

Although malatang originated in Sichuan, it is now common all over China. What makes Tianshui malatang stand out is its “Gansu-style” take, with a special focus on hand-pulled noodles, potato, and spicy oil.

An important ingredient for the soup base is the somewhat sweet and fragrant Gangu chili, produced in Tianshui’s Gangu County, known as “the hometown of peppers.”

Another ingredient is Maiji peppercorns (used in the sauce), and there are more locally produced ingredients, such as the black fungi from Qingshui County.

One restaurant that made Tianshui’s malatang particularly famous is Haiying Malatang (海英麻辣烫) in the city’s Qinzhou District. On February 13, the tiny restaurant, which has been around for three decades, welcomed an online influencer (@一杯梁白开) who posted about her visit.

The vlogger was so enthusiastic about her taste of “Gansu-style malatang,” that she urged her followers to try it out. It was the start of something much bigger than she could have imagined.

Replicating Zibo

Tianshui isn’t the first city to capture the spotlight on Chinese social media. Cities such as Zibo and Harbin have previously surged in popularity, becoming overnight sensations on platforms like Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin.

This phenomenon of Chinese cities transforming into hot travel destinations due to social media frenzy became particularly noteworthy in early 2023.

During the Covid years, various factors sparked a friendly competition among Chinese cities, each competing to attract the most visitors and to promote their city in the best way possible.

The Covid pandemic had diverse impacts on the Chinese domestic tourism industry. On one hand, domestic tourism flourished due to the pandemic, as Chinese travelers opted for destinations closer to home amid travel restrictions. On the other hand, the zero-Covid policy, with its lockdowns and the absence of foreign visitors, posed significant challenges to the tourism sector.

Following the abolition of the zero-Covid policy, tourism and marketing departments across China swung into action to revitalize their local economy. China’s social media platforms became battlegrounds to capture the attention of Chinese netizens. Local government officials dressed up in traditional outfits and created original videos to convince tourists to visit their hometowns.

Zibo was the first city to become an absolute social media sensation in the post-Covid era. The old industrial and mining city was not exactly known as a trendy tourist destination, but saw its hotel bookings going up 800% in 2023 compared to pre-Covid year 2019. Among others factors contributing to its success, the city’s online marketing campaign and how it turned its local BBQ culture into a unique selling point were both critical.

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Since 2023, multiple cities have tried to replicate the success of Zibo. Although not all have achieved similar results, Harbin has done very well by becoming a meme-worthy tourist attraction earlier in 2024, emphasizing its snow spectacle and friendly local culture.

By promoting its distinctive take on malatang, Tianshui has emerged as the next city to captivate online audiences, leading to a surge in visitor numbers.

Like with Zibo and Harbin, one particular important strategy used by these tourist offices is to swiftly respond to content created by travel bloggers or food vloggers about their cities, boosting the online attention and immediately seizing the opportunity to turn online success into offline visits.

A Timeline

What does it take to become a Chinese ‘celebrity city’? Since late February and early March of this year, various Douyin accounts started posting about Tianshui and its malatang.

They initially were the main reason driving tourists to the city to try out malatang, but they were not the only reason – city marketing and state media coverage also played a role in how the success of Tianshui played out.

Here’s a timeline of how its (online) frenzy unfolded:

- July 25, 2023: First video on Douyin about Tianshui’s malatang, after which 45 more videos by various accounts followed in the following six months.

- Feb 5, 2024: Douyin account ‘Chuanshuo Zhong de Bozi’ (传说中的波仔) posts a video about malatang streetfood in Gansu

- Feb 13, 2024: Douyin account ‘Yibei Liangbaikai’ (一杯梁白开) posts a video suggesting the “nationwide popularization of Gansu-style malatang.” This video is an important breakthrough moment in the success of Tianshui as a malatang city.

- Feb – March ~, 2024: The Tianshui Culture & Tourism Bureau is visiting sites, conducting research, and organizing meetings with different departments to establish the “Tianshui city + malatang” brand (文旅+天水麻辣烫”品牌) as the city’s new “business card.”

- March 11, 2024: Tianshui city launches a dedicated ‘spicy and hot’ bus line to cater to visitors who want to quickly reach the city’s renowned malatang spots.

- March 13-14, 2024: China’s Baidu search engine witnesses exponential growth in online searches for Tianshui malatang.

- March 14-15, 2024: The boss of Tianshui’s popular Haiying restaurant goes viral after videos show him overwhelmed and worried he can’t keep up. His facial expression becomes a meme, with netizens dubbing it the “can’t keep up-expression” (“烫不完表情”).

The worried and stressed expression of this malatang diner boss went viral overnight.

- March 17, 2024: Chinese media report about free ‘Tianshui malatang’ wifi being offered to visitors as a special service while they’re standing in line at malatang restaurants.

- March 18, 2024: Tianshui opens its first ‘Malatang Street’ where about 40 stalls sell malatang.

- March 18, 2024: Chinese local media report that one Tianshui hair salon (Tony) has changed its shop into a malatang shop overnight, showing just how big the hype has become.

- March 21, 2024: A dedicated ‘Tianshui malatang’ train started riding from Lanzhou West Station to Tianshui (#天水麻辣烫专列开行#).

- March 21, 2024: Chinese actor Jia Nailiang (贾乃亮) makes a video about having Tianshui malatang, further adding to its online success.

- March 30, 2024: A rare occurrence: as the main attraction near Tianshui, the Maiji Mountain Scenic Area announces that they’ve reached the maximum number of visitors and don’t have the capacity to welcome any more visitors, suspending all ticket sales for the day.

- April 1, 2024: Chinese presenter Zhang Dada was spotted making malatang in a local Tianshui restaurant, drawing in even more crowds.

A New Moment to Shine

Fame attracts criticism, and that also holds true for China’s ‘celebrity cities.’

Some argue that Tianshui’s malatang is overrated, considering the richness of Gansu cuisine, which offers much more than just malatang alone.

When Zibo reached hype status, it also faced scrutiny, with some commenters suggesting that the popularity of Zibo BBQ was a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and “empty social spectacle.”

There is a lot to say about the downsides of suddenly becoming a ‘celebrity city’ and the superficiality and fleetingness that comes with these kinds of trends. But for many locals, it is seen as an important moment as they see their businesses and cities thrive.

Even after the hype fades, local businesses can maintain their success by branding themselves as previously viral restaurants. When I visited Zibo a few months after its initial buzz, many once-popular spots marketed themselves as ‘wanghong’ (网红) or viral celebrity restaurants.

For the city itself, being in the spotlight holds its own value in the long run. Even after the hype has peaked and subsided, the gained national recognition ensures that these “trendy” places will continue to attract visitors in the future.

According to data from Ctrip, Tianshui experienced a 40% increase in tourism spending since March (specifically from March 1st to March 16th). State media reports claim that the city saw 2.3 million visitors in the first three weeks of March, with total tourism revenue reaching nearly 1.4 billion yuan ($193.7 million).

There are more ripple effects of Tianshui’s success: Maiji Shan Grottoes are witnessing a surge in visitors, and local e-commerce companies are experiencing a spike in orders from outside the city. Even when they’re not in Tianshui, people still want a piece of Tianshui.

By now, it’s clear that tourism marketing in China will never be the same again. Zibo, Harbin, and Tianshui exemplify a new era of destination hype, requiring a unique selling point, social media success, strong city marketing, and a friendly and fair business culture at the grassroots level.

While Zibo’s success was largely organic, Harbin’s was more orchestrated, and Tianshui learned from both. Now, other potential ‘celebrity’ cities are preparing to go viral, learning from the successes and failures of their predecessors to shine when their time comes.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

In Hot Water: The Nongfu Spring Controversy Explained

Nongfu and nationalists: how the praise for one Chinese domestic water bottle brand sparked online animosity toward another.

Published

1 month agoon

March 14, 2024

PREMIUM CONTENT

The big battle over bottled water has taken over Chinese social media recently. The support for the Chinese Wahaha brand has morphed into an anti-Nongfu Spring campaign, led by online nationalists.

Recently, China’s number one water brand, Nongfu Spring (农夫山泉) has found itself in the midst of an online nationalist storm.

The controversy started with the passing of Zong Qinghou (宗庆后), the founder and chairman of Wahaha Group (娃哈哈集团), the largest beverage producer in China. News of his passing made headlines on February 25, 2024, with one Weibo hashtag announcing his death receiving over 900 million views (#宗庆后逝世#).

The death of the businessman led to an outpouring of emotions on Weibo, where netizens praised his work ethic, dedication, and unwavering commitment to his principles.

Zong Qinghou, image via Weibo.

Born in 1945, Zong established Wahaha in Hangzhou in 1987, starting from scratch alongside two others. Despite humble beginnings, Zong, who came from a poor background, initially sold ice cream and soft drinks from his tricycle. However, by the second year, the company achieved success by concentrating on selling nutritional drinks to children, a strategy that resonated with Chinese single-child families (Tsui et al., 2017, p. 295).

The company experienced explosive growth and, boasting over 150 products ranging from milk drinks to fruit juices and soda pops, emerged as a dominant force in China’s beverage industry and the largest domestic bottled-water company.

Big bottle of Wahaha (meaning “laughing child”) water.

The admiration for Zong Qinghou and his company relates to multiple factors. Zong was loved for his inspirational rags-to-riches story under China’s economic reform, not unlike the self-made Tao Huabi and her Laoganma brand.

He was also loved for establishing a top Chinese national brand and refusing to be bought out. A decade after Wahaha partnered with the France-based multinational Danone in 1996, the two companies clashed when Zong accused Danone of trying to take over the Wahaha brand, which turned into a high-profile legal battle that was eventually settled in 2009, when Danone eventually sold all its stakes.

It is one of the reasons why Zong was known as a “patriotic private entrepreneur” (爱国民营企业家) who remained devoted to China and his roots.

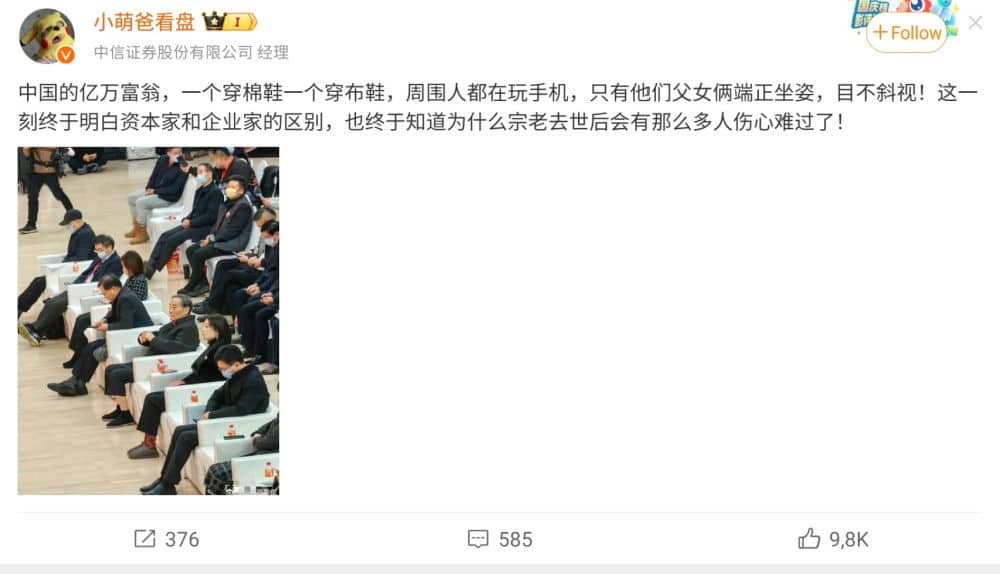

Netizens also admire the Chinese tycoon’s modesty and humility despite his immense wealth. He would often wear simple cloth shoes and, apparently not caring much about the elite social stratum, allegedly declined invitations to dine with Bill Gates and the Queen of England. He had a people-centric business approach. He prioritized the welfare of Wahaha employees, ensuring the protection of pensions for retired workers, establishing an employee stock ownership plan, and refused to terminate employees older than 45.

A post praising Zong and his daughter for staying humble despite their wealth: wearing simple shoes and not looking at their phones.

Zong and his daughter stand out due to their simple shoes.

As a tribute to Zong following his passing in late February, people not only started buying Wahaha bottled water, they also initiated criticism against its major competitor, Nongfu Spring (农夫山泉). Posts across various Chinese social media platforms, from Douyin to Weibo, started to advocate for boycotting Nongfu as a means to “protect” Wahaha as a national, proudly made-in-China brand.

From Love for Wahaha to Hate for Nongfu

With the death of Zong Qinghou, it seems that the decades-long rivalry between Nongfu and Wahaha has suddenly taken center stage in the public opinion arena, and it’s clear who people are rooting for.

The founder and chairman of Nongfu Spring is Chinese entrepreneur Zhong Shanshan (钟睒睒), and he is perhaps less likeable than Zong Qinghou, in part because he is not considered as patriotic as him.

Born in 1954, Zhong Shanshan is a former journalist who started working for Wahaha in the early 1990s. He established his own company and started focusing on bottled water in 1996. He would become China’s richest man.

His wealth was not just accumulated because of his Nongfu Spring water, which would become a leader in China’s bottled water market. Zhong also became the largest shareholder of Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise, which experienced significant growth following its IPO. Cecolin, a vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV), is manufactured by Innovax, a wholly owned subsidiary of Wantai.

Zhong Shanshan, image via Sohu.

The fact that Zhong Shanshan previously worked for Zong Qinghou and later ventured out on his own does not cast him in a positive light, especially in the context of netizens mourning Zong. Many people perceive Zhong Shanshan as a profit-driven businessman who lacks humility and national spirit compared to his former boss. Some even label him as ‘ungrateful.’

By now, the support for Wahaha water has snowballed into an anti-Nongfu campaign, resulting in intense scrutiny and criticism directed at the brand and its owner. This has led to a significant boycott and a sharp decline in sales.

Netizens are finding multiple reasons to attack Nongfu Spring and its owner. Apart from accusing Zhong Shanshan of being ungrateful, one of the Nongfu brand’s product packaging designs has also sparked controversy. The packaging of its Oriental Leaf Green Tea has been alleged to show Japanese elements, leading to claims of Zhong being “pro-Japan.”

Chinese social media users claim the packaging of this green tea is based on Japanese architecture instead of Chinese buildings.

Another point of ongoing contention is the fact that Zhong’s son (his heir, Zhong Shuzi 钟墅子) holds American citizenship. This has sparked anger among netizens who question Zhong’s allegiance to China. Concerned that the future of Nongfu might be in the US instead of China, they accuse Zhong and his business of betraying the Chinese people and being unpatriotic.

But what also plays a role in this, is how Zhong and the Nongfu Spring PR team have responded to the ongoing criticism. Some bloggers (link, link) argue their approach lacks emotional connection and comes off as too business-like.

On March 3rd, Zhong himself issued a statement addressing the personal attacks he faced following the passing of Zong Qinghou. In his article (我与宗老二三事), he aimed to ‘set the record straight.’ Although he expressed admiration for Zong Qinghou, many found his piece to be impersonal and more focused on safeguarding his own image.

The same criticism goes for the company’s response to the “pro-Japan” issue. On March 7, they refuted ongoing accusations and stated that the architecture depicted on the controversial beverage packaging was inspired by Chinese temples, not Japanese ones, and that a text on the bottle is about Japanese tea culture originating from China.

Calls for Calmer Water

Although Weibo and other social media platforms in China have recently seen a surge in nationalism, not everybody agrees with the way Nongfu Spring is being attacked. Some say that netizens are taking it too far and that a vocal minority is controlling the trending narrative.

Posts or videos from people pouring out Nongfu water in their sink are countered by others from people saying that they are now buying the brand to show solidarity in the midst of the social media storm.

Online photo of netizen buying Nongfu Spring water: “I support Nongfu Spring, I support private entrepreneurs, I support the recovery of China’s economy. I firmly opposo populism running wild.”

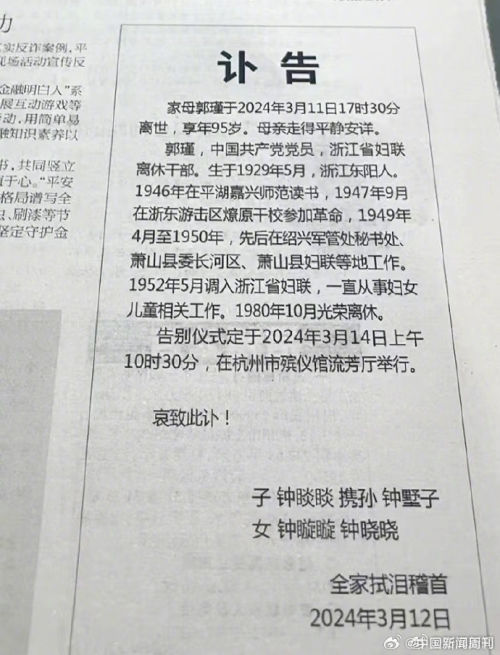

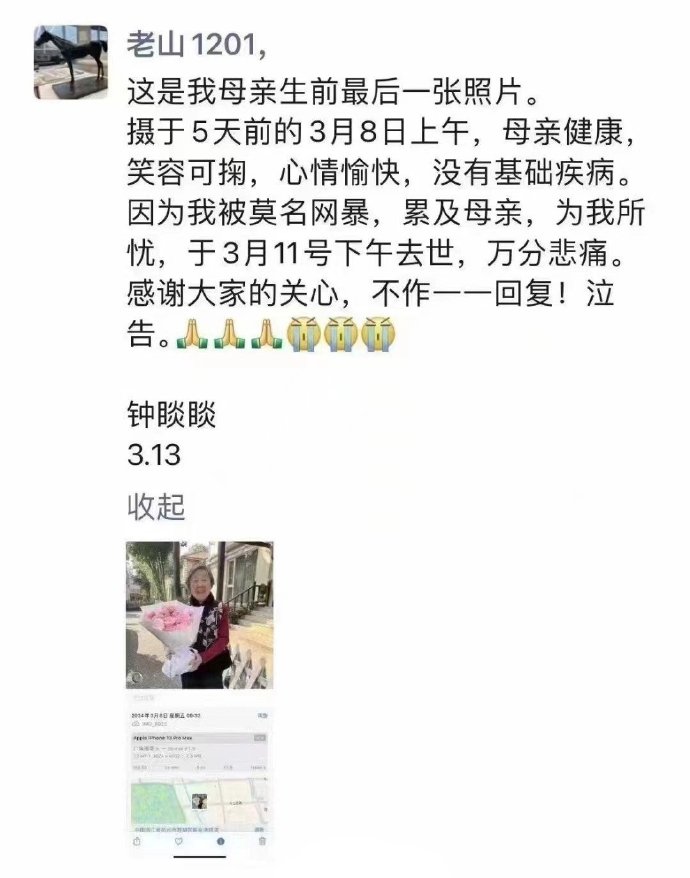

While more people are speaking out against the recent waves of nationalism, news came in on March 13 that the 95-year-old mother of Zhong Shanshan had passed away. According to an obituary published in the Qianjiang Evening News newspaper, Guo Jin (郭瑾) passed away on March 11.

The obituary.

A screenshot of a WeChat post alleged to be written by Zhong Shanshan made its rounds, in which Zhong blamed the online hate he received, and the ensuing stress, for his mother’s death.

While criticism of Zhong resurfaced for attributing the old lady’s death to “indescribable cyberbullying” (“莫名网暴”), some saw this moment as an opportunity to bring an end to the attacks on Nongfu. As the controversy continued to brew, the Sina Weibo platform seemingly attempted to divert attention by removing some hashtags related to the issue (e.g., “Zhong Shanshan’s Mother Guo Jin Passed Away” #钟睒睒之母郭瑾离世#).

The well-known Chinese commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) also spoke out in support of Nongfu Spring and called for rationality, arguing that Chinese private entrepreneurs are facing excessive scrutiny. He suggested that China’s netizens should stop nitpicking over their private matters and instead focus more on their contributions to the country’s economy.

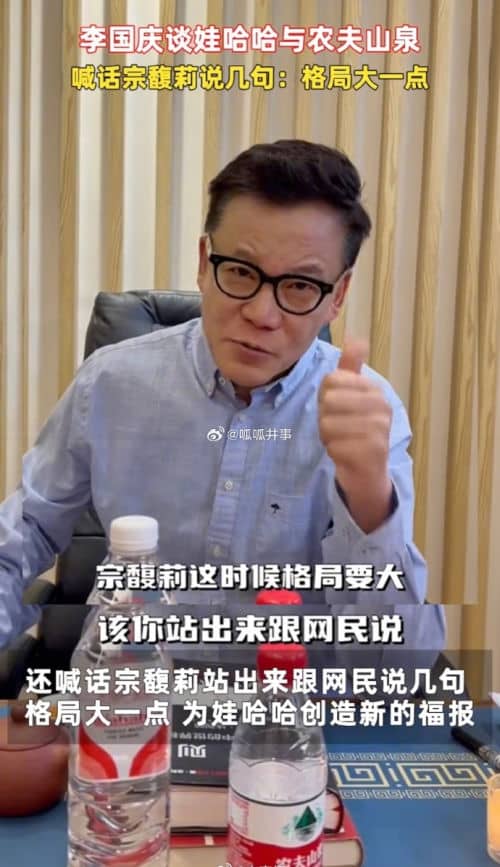

Others are also calling for an end to the waves of attacks towards Nongfu and Zhong Shanshan. Chinese entrepreneur Li Guoqing (李国庆), co-founder of the e-commerce company Dangdang (once hailed as the ‘Amazon of China’), posted a video about the issue on March 12. He said: “These two [Nongfu Spring and Wahaha brands] have come a long way to get to where they are today. The fact that they are competitors is a good thing. If old Zong [Qinghou] were still alive today and saw this division, he would surely step forward and tell people to get back to business and rational competition.”

Li Guoqing in his video (since deleted).

Li also suggested that Zong’s heir, his daughter Kelly Zong, should come out, broaden her perspective, and settle the matter. She should thank netizens for their support, he argued, and tell them that it is completely unnecessary to exacerbate the rift with Nongfu Spring in showing their support.

But those mingling in the matter soon discover themselves how easy it is to get your fingers burned on this hot topic. Li Guoqing might have meant well, but he also faced attacks after his video. Not only because people feel he is putting Kelly Zong in an awkward position, but also because his own son. like Zhong Shuzi, allegedly holds American citizenship. Perhaps unwilling to find himself in hot water as well, Li Guoqing has since deleted his video. The Nongfu storm may be one that should blow over by itself.

By Manya Koetse

With contributions by Miranda Barnes

References

Tsui, Anne S., Yingying Zhang, Xiao-Ping Chen. 2017. “Chinese Companies Need Strong and Open-minded Leaders. Interview with Wahaha Group Founder, Chairman and CEO, Qinghou Zong.” In Leadership of Chinese Private Enterprises

Insights and Interviews, Palgrave MacMillan.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

Weibo Watch: Burning BMWs

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

A Snowball Effect: How Cold Harbin Became the Hottest Place in China

Jia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Weibo Watch: Frogs in Wells

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight1 month ago

China Insight1 month agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoA Snowball Effect: How Cold Harbin Became the Hottest Place in China

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoJia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

-

China Arts & Entertainment2 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment2 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Wulfgul

April 18, 2019 at 8:10 pm

Might as well cover this article while you are at it.

https://www.weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309404362357362038276#_0

Admin

April 19, 2019 at 11:52 am

Wow, very interesting, thank you. Think we’ve written enough about this topic for now though. Thanks anyway!