China Media

Chinese State Media Features German Twitterer “Defamed by Evil Western Forces”

European media call the 21-year-old Heyden a CCP propagandist, Chinese media call her a victim of the Western media agenda.

Published

3 years agoon

The German influencer Navina Heyden has been labeled “a propagandist for the Chinese government” by European media outlets. She is now featured by Global Times for preparing a lawsuit against German newspaper Die Welt for “defaming” her.

A 21-year-old woman from Germany has been attracting attention on Chinese social media this week after state media outlet Global Times published an article about her battle against “biased journalism” in Europe.

She is known by her Chinese name of Hǎiwénnà 海雯娜 on Weibo, but also by her German name, Navina Heyden. On Twitter (@NavinaHeyden) she has around 34K followers, on Weibo (@海雯娜NavinaHeyden) she has over 15800 fans.

According to the Global Times story, which is titled “21-year-old German Girl Debunking China’s Defamation Is Tragically Strangled by Evil Western Forces” [“21岁德国女孩驳斥对中国抹黑,惨遭西方恶势力绞杀”], Heyden has been on a mission to “refute Western media’s smear campaign against China” for the past year.

The same article was also published by other Chinese state media outlets this week, including Xinhua, Xinmin, and Beijing Times.

Recently, various European news outlets reporting about Heyden’s online activities described her as a Twitter influencer acting as an advocate for “pro-CCP narratives.”

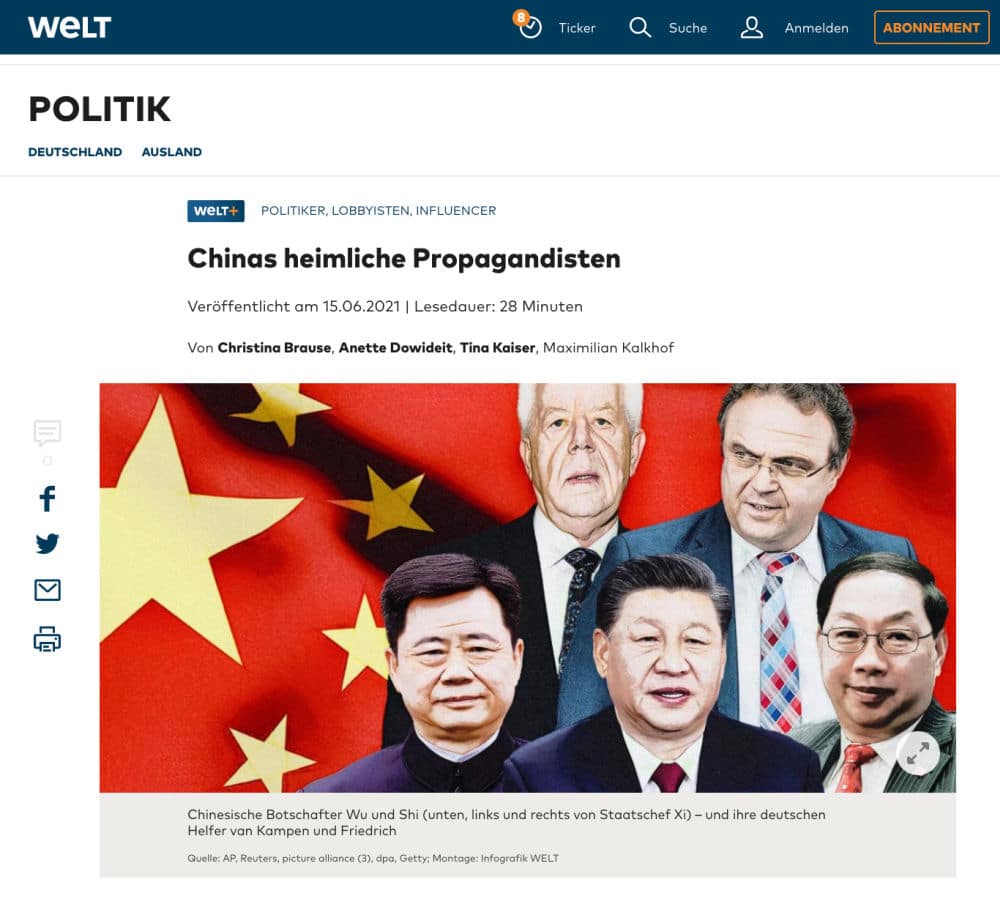

It started with the German newspaper Welt am Sonntag publishing an article on June 15 of 2021 titled “China’s Secret Propagandists” [“Chinas Heimliche Propagandisten”], in which Heyden was accused of being a propagandist. That same story was translated into French and published by Le Soir on June 23.

An article by London-based think tank ISD (Institute for Strategic Dialogue) dated June 10, titled “How a Pro-CCP Twitter Network is Boosting the Popularity of Western Influencers” (link), also featured Heyden and her alleged role in a coordinated Chinese online propaganda campaign.

The article focuses on Heyden’s Twitter activity and her supposedly inorganic follower growth, using data research to support the claim that she is more than just a young woman siding with Chinese official views.

Heyden claims that she agreed to do the initial interview with Die Welt about her views on China and the online harassment she experienced by anti-China activists, but that the reporters eventually published something that was very different from the actual interview content, describing Heyden as a Chinese government propagandist and disclosing names and locations without her consent.

Heyden says she is now preparing a lawsuit against the newspaper and its three journalists for violating her rights. In order to do so, she started a crowdfunding campaign to help her fight media defamation. That ‘Go Fund Me’ campaign was also promoted on Weibo on July 5th, and she soon reached over 13,000 euros in donations.

The main take-away of the Global Times story is that Heyden is an active social media user who has bravely refuted Western bias on China and exposed the supposed media hysteria regarding the rise of China, and that she has been purposely targeted by European media outlets for doing so.

Heyden joined Twitter in March of 2020 with her bio describing her as a “German amateur manga drawer, studying business economy, grown up within Chinese community since age 15.”

Since then, she has tweeted over 1000 times and has spoken out about many issues involving China, including the Covid-19 pandemic, the situation in Xinjiang, the national security law in Hong Kong, the India-China border conflict, and the status of Taiwan. She sometimes also tweets out more personal information, such as the time when she shared photos of herself and her Chinese partner.

Her very first tweet on the platform – one about China not falsifying Covid-19 numbers – was sent out on April 1st of 2020 and received 52 likes. Over the past year, her account has only gained more likes and followers.

A later tweet in which Heyden wrote “I can testify that Chinese Muslims are not persecuted like what western media claimed” (link) received over 870 likes.

In another tweet, Heyden wrote: “China is unfairly treated because she’s always put in a trial without chances to defend. Her words must be propaganda, her people must be brainwashed. After confirmation with Chinese sources and my experiences, I’m enraged about how wrong our media is. This is harmful to us all.” That tweet received over 1.4K likes.

Besides the fact that Heyden’s tweets are often retweeted by the Twitter accounts of Chinese diplomats and other prominent Chinese channels – sometimes within just a few seconds of one another, – the aforementioned ISD article claims that Heyden’s account has grown in a relatively short time due to sudden spikes in followership by accounts that were created in batches at specific times and in short sequence.

For a Twitter post of August 2020, Heyden recorded a video in which she explained why she wanted to open up her Twitter account in the first place and counter those accusing her of being a “CCP agent” or a “fake account”. She said:

“I’m not getting paid by anyone so stop wasting your time on proving something which I am not. A lot of people may wonder why I say so many positive things about China in the first place. The reason is that when I was around 15 years old I was introduced into the Chinese community and I got to learn a lot of Chinese people, what they think about China, and also what they think about their government. And I found that the China I visited is so much different from the China that the media is describing. It’s almost as if the media is describing a whole different country. Now, it wouldn’t be so bad if only people would not buy those false narratives, and I’m having a problem with it, because a lot of my close friends and also my family are believing all those false narratives. And this is causing me to have some conflicts with them from time to time. So I’ve decided to open this Twitter account to debunk all those false narratives.”

At this time, Heyden describes her own Twitter account as “one of the most influential ones to show people what real China is like.”

The story about Heyden’s online activities seems to suit some ongoing narratives in both European and Chinese newspapers. For the first, it upholds the idea of China secretly attempting to infiltrate and influence democratic societies in new ways; for the latter, it confirms the belief that biased Western media will do anything to defile China while serving the interests of their political parties.

Meanwhile, on Weibo, hundreds of netizens have praised Heyden for defending China and standing up against Western media.

“China has 1.4 billion people, Germany just has [tens] millions, of course, you’re gonna get a lot of fans if you support China,” one popular comment on Weibo said.

One influential Weibo blogger (@文创客) wrote about Heyden, calling her a victim of a “deranged” situation where Western media outlets have used her for their anti-China narratives.

“When will you come and live in China,” some people on Weibo ask, with various other commenters saying: “Just come to China!”

Plans to move to China seem to be on the horizon for the German influencer. In an earlier tweet, she confirmed: “We are already on the path to live in China PERMANENTLY. Really feel much safer there.”

Despite sharing her strong support for China on Twitter, the 21-year-old recently also expressed some frustrations with the Chinese social media climate when she encountered censorship on Sina Weibo and experienced some difficulties posting on Bilibili and Toutiao.

On Twitter, she wrote: “To CPC, you can’t lock your citizens in an information greenhouse forever.”

Sharing some of her frustrations regarding the Chinese social media sphere on Weibo, where she even admitted to missing Twitter, some Weibo users offered their support: “We’re on your side.”

By Manya Koetse (@manyapan)

With contributions by Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2021 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Zibo had its BBQ moment. Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine with its special take on malatang. Tourism marketing in China will never be the same again.

Published

3 weeks agoon

April 1, 2024

Since the early post-pandemic days, Chinese cities have stepped up their game to attract more tourists. The dynamics of Chinese social media make it possible for smaller, lesser-known destinations to gain overnight fame as a ‘celebrity city.’ Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine.

During this Qingming Festival holiday, there is one Chinese city that will definitely welcome more visitors than usual. Tianshui, the second largest city in Gansu Province, has emerged as the latest travel hotspot among domestic tourists following its recent surge in popularity online.

Situated approximately halfway along the Lanzhou-Xi’an rail line, this ancient city wasn’t previously a top destination for tourists. Most travelers would typically pass through the industrial city to see the Maiji Shan Grottoes, the fourth largest Buddhist cave complex in China, renowned for its famous rock carvings along the Silk Road.

But now, there is another reason to visit Tianshui: malatang.

Gansu-Style Malatang

Málàtàng (麻辣烫), which literally means ‘numb spicy hot,’ is a popular Chinese street food dish featuring a diverse array of ingredients cooked in a soup base infused with Sichuan pepper and dried chili pepper. There are multiple ways to enjoy malatang.

When dining at smaller street stalls, it’s common to find a selection of skewered foods—ranging from meats to quail eggs and vegetables—simmering in a large vat of flavorful spicy broth. This communal dining experience is affordable and convenient for solo diners or smaller groups seeking a hotpot-style meal.

In malatang restaurants, patrons can usually choose from a selection of self-serve skewered ingredients. You have them weighed, pay, and then have it prepared and served in a bowl with a preferred soup base, often with the option to choose the level of spiciness, from super hot to mild.

Although malatang originated in Sichuan, it is now common all over China. What makes Tianshui malatang stand out is its “Gansu-style” take, with a special focus on hand-pulled noodles, potato, and spicy oil.

An important ingredient for the soup base is the somewhat sweet and fragrant Gangu chili, produced in Tianshui’s Gangu County, known as “the hometown of peppers.”

Another ingredient is Maiji peppercorns (used in the sauce), and there are more locally produced ingredients, such as the black fungi from Qingshui County.

One restaurant that made Tianshui’s malatang particularly famous is Haiying Malatang (海英麻辣烫) in the city’s Qinzhou District. On February 13, the tiny restaurant, which has been around for three decades, welcomed an online influencer (@一杯梁白开) who posted about her visit.

The vlogger was so enthusiastic about her taste of “Gansu-style malatang,” that she urged her followers to try it out. It was the start of something much bigger than she could have imagined.

Replicating Zibo

Tianshui isn’t the first city to capture the spotlight on Chinese social media. Cities such as Zibo and Harbin have previously surged in popularity, becoming overnight sensations on platforms like Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin.

This phenomenon of Chinese cities transforming into hot travel destinations due to social media frenzy became particularly noteworthy in early 2023.

During the Covid years, various factors sparked a friendly competition among Chinese cities, each competing to attract the most visitors and to promote their city in the best way possible.

The Covid pandemic had diverse impacts on the Chinese domestic tourism industry. On one hand, domestic tourism flourished due to the pandemic, as Chinese travelers opted for destinations closer to home amid travel restrictions. On the other hand, the zero-Covid policy, with its lockdowns and the absence of foreign visitors, posed significant challenges to the tourism sector.

Following the abolition of the zero-Covid policy, tourism and marketing departments across China swung into action to revitalize their local economy. China’s social media platforms became battlegrounds to capture the attention of Chinese netizens. Local government officials dressed up in traditional outfits and created original videos to convince tourists to visit their hometowns.

Zibo was the first city to become an absolute social media sensation in the post-Covid era. The old industrial and mining city was not exactly known as a trendy tourist destination, but saw its hotel bookings going up 800% in 2023 compared to pre-Covid year 2019. Among others factors contributing to its success, the city’s online marketing campaign and how it turned its local BBQ culture into a unique selling point were both critical.

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Since 2023, multiple cities have tried to replicate the success of Zibo. Although not all have achieved similar results, Harbin has done very well by becoming a meme-worthy tourist attraction earlier in 2024, emphasizing its snow spectacle and friendly local culture.

By promoting its distinctive take on malatang, Tianshui has emerged as the next city to captivate online audiences, leading to a surge in visitor numbers.

Like with Zibo and Harbin, one particular important strategy used by these tourist offices is to swiftly respond to content created by travel bloggers or food vloggers about their cities, boosting the online attention and immediately seizing the opportunity to turn online success into offline visits.

A Timeline

What does it take to become a Chinese ‘celebrity city’? Since late February and early March of this year, various Douyin accounts started posting about Tianshui and its malatang.

They initially were the main reason driving tourists to the city to try out malatang, but they were not the only reason – city marketing and state media coverage also played a role in how the success of Tianshui played out.

Here’s a timeline of how its (online) frenzy unfolded:

- July 25, 2023: First video on Douyin about Tianshui’s malatang, after which 45 more videos by various accounts followed in the following six months.

- Feb 5, 2024: Douyin account ‘Chuanshuo Zhong de Bozi’ (传说中的波仔) posts a video about malatang streetfood in Gansu

- Feb 13, 2024: Douyin account ‘Yibei Liangbaikai’ (一杯梁白开) posts a video suggesting the “nationwide popularization of Gansu-style malatang.” This video is an important breakthrough moment in the success of Tianshui as a malatang city.

- Feb – March ~, 2024: The Tianshui Culture & Tourism Bureau is visiting sites, conducting research, and organizing meetings with different departments to establish the “Tianshui city + malatang” brand (文旅+天水麻辣烫”品牌) as the city’s new “business card.”

- March 11, 2024: Tianshui city launches a dedicated ‘spicy and hot’ bus line to cater to visitors who want to quickly reach the city’s renowned malatang spots.

- March 13-14, 2024: China’s Baidu search engine witnesses exponential growth in online searches for Tianshui malatang.

- March 14-15, 2024: The boss of Tianshui’s popular Haiying restaurant goes viral after videos show him overwhelmed and worried he can’t keep up. His facial expression becomes a meme, with netizens dubbing it the “can’t keep up-expression” (“烫不完表情”).

The worried and stressed expression of this malatang diner boss went viral overnight.

- March 17, 2024: Chinese media report about free ‘Tianshui malatang’ wifi being offered to visitors as a special service while they’re standing in line at malatang restaurants.

- March 18, 2024: Tianshui opens its first ‘Malatang Street’ where about 40 stalls sell malatang.

- March 18, 2024: Chinese local media report that one Tianshui hair salon (Tony) has changed its shop into a malatang shop overnight, showing just how big the hype has become.

- March 21, 2024: A dedicated ‘Tianshui malatang’ train started riding from Lanzhou West Station to Tianshui (#天水麻辣烫专列开行#).

- March 21, 2024: Chinese actor Jia Nailiang (贾乃亮) makes a video about having Tianshui malatang, further adding to its online success.

- March 30, 2024: A rare occurrence: as the main attraction near Tianshui, the Maiji Mountain Scenic Area announces that they’ve reached the maximum number of visitors and don’t have the capacity to welcome any more visitors, suspending all ticket sales for the day.

- April 1, 2024: Chinese presenter Zhang Dada was spotted making malatang in a local Tianshui restaurant, drawing in even more crowds.

A New Moment to Shine

Fame attracts criticism, and that also holds true for China’s ‘celebrity cities.’

Some argue that Tianshui’s malatang is overrated, considering the richness of Gansu cuisine, which offers much more than just malatang alone.

When Zibo reached hype status, it also faced scrutiny, with some commenters suggesting that the popularity of Zibo BBQ was a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and “empty social spectacle.”

There is a lot to say about the downsides of suddenly becoming a ‘celebrity city’ and the superficiality and fleetingness that comes with these kinds of trends. But for many locals, it is seen as an important moment as they see their businesses and cities thrive.

Even after the hype fades, local businesses can maintain their success by branding themselves as previously viral restaurants. When I visited Zibo a few months after its initial buzz, many once-popular spots marketed themselves as ‘wanghong’ (网红) or viral celebrity restaurants.

For the city itself, being in the spotlight holds its own value in the long run. Even after the hype has peaked and subsided, the gained national recognition ensures that these “trendy” places will continue to attract visitors in the future.

According to data from Ctrip, Tianshui experienced a 40% increase in tourism spending since March (specifically from March 1st to March 16th). State media reports claim that the city saw 2.3 million visitors in the first three weeks of March, with total tourism revenue reaching nearly 1.4 billion yuan ($193.7 million).

There are more ripple effects of Tianshui’s success: Maiji Shan Grottoes are witnessing a surge in visitors, and local e-commerce companies are experiencing a spike in orders from outside the city. Even when they’re not in Tianshui, people still want a piece of Tianshui.

By now, it’s clear that tourism marketing in China will never be the same again. Zibo, Harbin, and Tianshui exemplify a new era of destination hype, requiring a unique selling point, social media success, strong city marketing, and a friendly and fair business culture at the grassroots level.

While Zibo’s success was largely organic, Harbin’s was more orchestrated, and Tianshui learned from both. Now, other potential ‘celebrity’ cities are preparing to go viral, learning from the successes and failures of their predecessors to shine when their time comes.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

Going All In on Short Streaming: About China’s Online ‘Micro Drama’ Craze

For viewers, they’re the ultimate guilty pleasure. For producers, micro dramas mean big profit.

Published

4 weeks agoon

March 26, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

PREMIUM CONTENT

Closely intertwined with the Chinese social media landscape and the fast-paced online entertainment scene, micro dramas have emerged as an immensely popular way to enjoy dramas in bite-sized portions. With their short-format style, these dramas have become big business, leading Chinese production studios to compete and rush to create the next ‘mini’ hit.

In February of this year, Chinese social media started flooding with various hashtags highlighting the huge commercial success of ‘online micro-short dramas’ (wǎngluò wēiduǎnjù 网络微短剧), also referred to as ‘micro drama’ or ‘short dramas’ (微短剧).

Stories ranged from “Micro drama screenwriters making over 100k yuan [$13.8k] monthly” to “Hengdian building earning 2.8 million yuan [$387.8k] rent from micro dramas within six months” and “Couple earns over 400 million [$55 million] in a month by making short dramas,” all reinforcing the same message: micro dramas mean big profits. (Respectively #短剧爆款编剧月入可超10万元#, #横店一栋楼半年靠短剧租金收入280万元#, #一对夫妇做短剧每月进账4亿多#.)

Micro dramas, taking China by storm and also gaining traction overseas, are basically super short streaming series, with each episode usually lasting no more than two minutes.

From Horizontal to Vertical

Online short dramas are closely tied to Chinese social media and have been around for about a decade, initially appearing on platforms like Youku and Tudou. However, the genre didn’t explode in popularity until 2020.

That year, China’s State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT) introduced a “fast registration and filing module for online micro dramas” to their “Key Online Film and Television Drama Information Filing System.” Online dramas or films can only be broadcast after obtaining an “online filing number.”

Chinese streaming giants such as iQiyi, Tencent, and Youku then began releasing 10-15 minute horizontal short dramas in late 2020. Despite their shorter length and faster pace, they actually weren’t much different from regular TV dramas.

Soon after, short video social platforms like Douyin (TikTok) and Kuaishou joined the trend, launching their own short dramas with episodes only lasting around 3 minutes each.

Of course, Douyin wouldn’t miss out on this trend and actively contributed to boosting the genre. To better suit its interface, Douyin converted horizontal-screen dramas into vertical ones (竖屏短剧).

Then, in 2021, the so-called mini-program (小程序) short dramas emerged, condensing each episode to 1-2 minutes, often spanning over 100 episodes.

These short dramas are advertised on platforms like Douyin, and when users click, they are directed to mini-programs where they need to pay for further viewing. Besides direct payment revenue, micro dramas may also bring in revenue from advertising.

‘Losers’ Striking Back

You might wonder what could possibly unfold in a TV drama lasting just two minutes per episode.

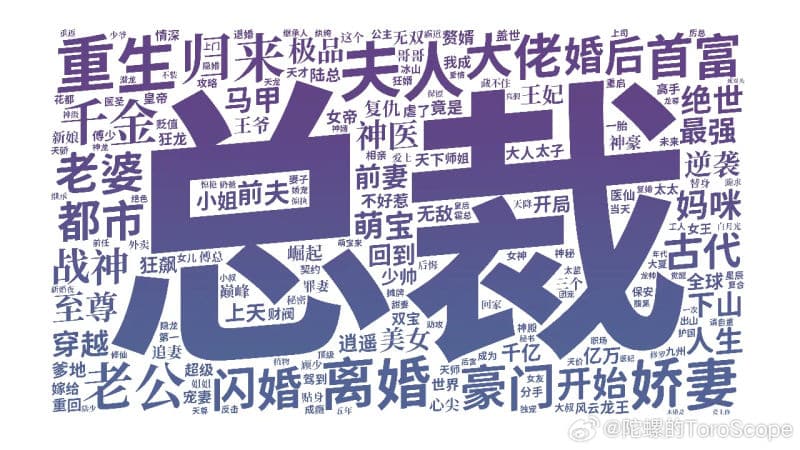

The Chinese cultural media outlet ‘Hedgehog Society’ (刺猬公社) collected data from nearly 6,000 short dramas and generated a word cloud based on their content keywords.

In works targeted at female audiences, the most common words revolve around (romantic) relationships, such as “madam” (夫人) and “CEO” (总裁). Unlike Chinese internet novels from over a decade ago, which often depicted perfect love and luxurious lifestyles, these short dramas offer a different perspective on married life and self-discovery.

According to Hedgehog Society’s data, the frequency of the term “divorce” (离婚) in short dramas is ten times higher than “married” (结婚) or “newlyweds” (新婚). Many of these dramas focus on how the female protagonist builds a better life after divorce and successfully stands up to her ex-husband or to those who once underestimated her — both physically and emotionally.

One of the wordclouds by 刺猬公社.

In male-oriented short dramas, the pursuit of power is a common theme, with phrases like “the strongest in history” (史上最强) and “war god” (战神) frequently mentioned. Another surprising theme is “matrilocal son” (赘婿), the son-in-law who lives with his wife’s family. In China, this term is derogatory, particularly referring to husbands with lower economic income and social status than their wives, which is considered embarrassing in traditional Chinese views. However, in these short dramas, the matrilocal son will employ various methods to earn the respect of his wife’s family and achieve significant success.

Although storylines differ, a recurring theme in these short dramas is protagonists wanting to turn their lives around. This desire for transformation is portrayed from various perspectives, whether it’s from the viewpoint of a wealthy, elite individual or from those with lower social status, such as divorced single women or matrilocal son-in-laws. This “feel-good” sentiment appears to resonate with many Chinese viewers.

Cultural influencer Lu Xuyu (@卢旭宁) quoted from a forum on short dramas, explaining the types of short dramas that are popular: Men seek success and admiration, and want to be pursued by beautiful women. Women seek romantic love or are still hoping the men around them finally wake up. One netizen commented more bluntly: “They are all about the counterattack of the losers (屌丝逆袭).”

The word used here is “diaosi,” a term used by Chinese netizens for many years to describe themselves as losers in a self-deprecating way to cope with the hardships of a competitive life, in which it has become increasingly difficult for Chinese youths to climb the social ladder.

Addicted to Micro Drama

By early 2024, the viewership of China’s micro dramas had soared to 120 million monthly active users, with the genre particularly resonating with lower-income individuals and the elderly in lower-tier markets.

However, short dramas also enjoy widespread popularity among many young people. According to data cited by Bilibili creator Caoxiaoling (@曹小灵比比叨), 64.9% of the audience falls within the 15-29 age group.

For these young viewers, short dramas offer rapid plot twists, meme-worthy dialogues, condensing the content of several episodes of a long drama into just one minute—stripping away everything except the pure “feel-good” sentiment, which seems rare in the contemporary online media environment. Micro dramas have become the ultimate ‘guilty pleasure.’

Various micro dramas, image by Sicomedia.

Even the renowned Chinese actress Ning Jing (@宁静) admitted to being hooked on short dramas. She confessed that while initially feeling “scammed” by the poor production and acting, she became increasingly addicted as she continued watching.

It’s easy to get hooked. Despite criticisms of low quality or shallowness, micro dramas are easy to digest, featuring clear storylines and characters. They don’t demand night-long binge sessions or investment in complex storylines. Instead, people can quickly watch multiple episodes while waiting for their bus or during a short break, satisfying their daily drama fix without investing too much time.

Chasing the gold rush

During the recent Spring Festival holiday, the Chinese box office didn’t witness significant growth compared to previous years. In the meantime, the micro drama “I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother” (我在八零年代当后妈), shot in just 10 days with a post-production cost of 80,000 yuan ($11,000), achieved a single-day revenue exceeding 2 million yuan ($277k). It’s about a college girl who time-travels back to the 1980s, reluctantly getting married to a divorced pig farm owner with kids, but unexpectedly falling in love.

Despite its simple production and clichéd plot, micro dramas like this are drawing in millions of viewers. The producer earned over 100 million yuan ($13 million) from this drama and another short one.

“I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother” (我在八零年代当后妈).

The popularity of short dramas, along with these significant profits, has attracted many people to join the short drama industry. According to some industry insiders, a short drama production team often involves hundreds or even thousands of contributors who help in writing scripts. These contributors include college students, unemployed individuals, and online writers — seemingly anyone can participate.

By now, Hengdian World Studios, the largest film and television shooting base in China, is already packed with crews filming short dramas. With many production teams facing a shortage of extras, reports have surfaced indicating significant increases in salaries, with retired civil workers even being enlisted as actors.

Despite the overwhelming success of some short dramas like “I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother,” it is not easy to replicate their formula. The screenwriter of the time-travel drama, Mi Meng (@咪蒙的微故事), is a renowned online writer who is very familiar with how to use online strategies to draw in more viewers. For many average creators, their short drama production journey is much more difficult and less fruitful.

But with low costs and potentially high returns, even if only one out of a hundred productions succeeds, it could be sufficient to recover the expenses of the others. This high-stakes, cutthroat competition poses a significant challenge for smaller players in the micro drama industry – although they actually fueled the genre’s growth.

As more scriptwriters and short dramas flood the market, leading to content becoming increasingly similar, the chances of making profits are likely to decrease. Many short drama platforms have yet to start generating net profits.

This situation has sparked concerns among netizens and critics regarding the future of short dramas. Given the genre’s success and intense competition, a transformation seems inevitable: only the shortest dramas that cater to the largest audiences will survive.

In the meantime, however, netizens are enjoying the hugely wide selection of micro dramas still available to them. One Weibo blogger, Renmin University Professor Ma Liang (@学者马亮), writes: “I spent some time researching short videos and watched quite a few. I must admit, once you start, you just can’t stop. ”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

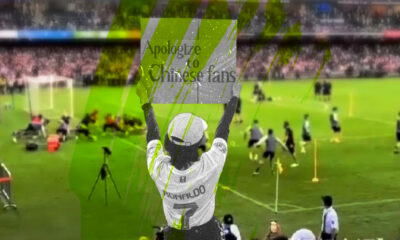

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

In Hot Water: The Nongfu Spring Controversy Explained

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

The Benz Guy from Baoding and the Granny Xu Line-Cutting Controversy

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

-

China World2 months ago

China World2 months agoFrom Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)