China Society

Cracking Down on ‘Unhealthy’ Wedding Customs: Xiong’an New Area Launches Wedding Reform Experiment

Are these announced reforms “neglecting the root and pursuing the tip” of existing problems with weddings and marriage in China?

Published

3 years agoon

Authorities in China’s Hebei want to curb ‘unhealthy’ wedding practices such as the custom of giving exorbitant bride prices. On social media, many people think the announced reforms ignore deeper structural inequalities in Chinese marriages.

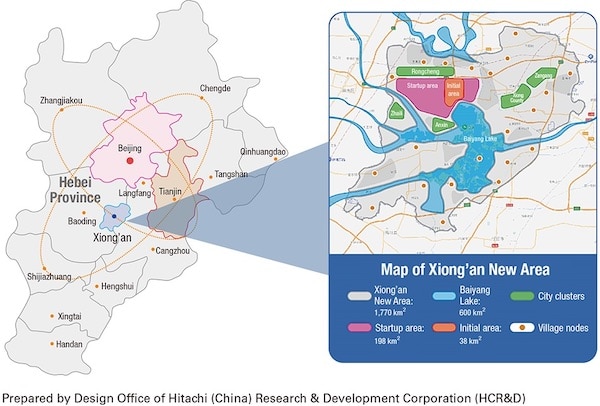

On May 26, Xiong’an New Area (雄安新区), the state-level new area in China’s Hebei Province, announced a reform experiment for local wedding customs.

The Hebei Provincial Department of Civil Affairs published a document on its website on May 24 on the reforms that will be tried out for the upcoming three years. The ‘experiment’ will be carried out in Xiong’an New Area, Baoding’s Lianchi district, Hengshui’s Jizhou district, Handan’s Feixiang district, and in Xinji city.

Xiong’an New Area is located south of Beijing, map by https://www.hitachi.com/rev/archive/2021/r2021_01/gir/index.html

The experimental reform will focus on curbing wedding customs such as bride prices, peer competition, ‘extravagance and wastefulness’ during weddings, and other practices that local authorities deem “unhealthy.”

On Weibo, one hashtag page dedicated to the topic (#雄安被确认为婚俗改革实验区#) received over 230 million views on May 26.

Weddings and marriage are always much-discussed topics on Chinese social media, especially over the past few years when the number of marriages in China saw a drastic decline. Over the past year, marriages in China saw the biggest drop in decades while the country’s divorce rate has been climbing.

Meanwhile, China’s population is aging and birth rates have fallen to record lows.

The custom of bride prices is one topic that has particularly sparked online discussions throughout the years.

Bride prices are a long-standing tradition in China. A ‘bride price’ is an amount of money or goods paid by the groom’s family to the bride’s family upon marriage. Since China’s gender imbalance has made it more difficult for men to find a bride, the ‘bridewealth’ prices have gone up drastically over the years. This holds especially true for the poorer, rural areas in China, where men are sometimes expected to pay staggering prices to their bride’s family before marriage.

Earlier this month, state media outlet Global Times reported that the high competition between men of marriageable age pushed up the price of brides in rural areas. The price of a bride in Jiaocun town was reported to be between 150,000 yuan ($23,295) and 200,000 yuan in 2017, and allegedly continues to rise by 10,000-20,000 yuan each year.

For many Chinese young people, getting married is not on the top of their wishlist. When a national survey recently revealed that one in five women in China regret getting married – another survey said it was 30% of women -, many commenters on social media suggested the actual number was probably much higher.

The fact that the package deal of marriage in China is unappealing to many people is linked to a myriad of issues, and many social media commenters remark that solely focusing on tackling the issue of wedding customs and bride prices is just “neglecting the root and pursuing the tip” (“舍本逐末”).

On Weibo, hundreds of commenters suggest that deeper issues relating to the status and rights of married women in China are more important to focus on.

“You neglect the fact that males are valued more than females, and instead prioritize the bride price issue,” one Weibo user complained. Many others agreed, with the following comments receiving much support on Weibo:

“Why can’t you focus on practical matters? The bride price isn’t the reason why our marriage rates are dropping.”

“How about the fact that the children always take on the father’s name, isn’t that a ‘wedding custom’? (..) How about gender equality? How are you planning to reform that?”

“This is done quite fast, how about dealing with domestic violence now?”

“It’s fine if you take away the bride price, but will [rural] women then also get a fair division of residential property?”

“First you introduce a cooling-off period for divorce, then you promote a cancelation of the bride price, then you propagate having a second or third child. It’s like these experts are in their offices all day long plotting against women and thinking of ways to maximize their exploitation.”

Last month, Chinese newspaper The Paper published a column by wedding blogger Zheng Rongxiang (郑荣翔) about the announced wedding reforms, which are also expected to roll out in other regions across China from Henan to Guangdong and beyond.

Zheng argues that many Chinese weddings have become a show of wealth, especially in the age of social media. Extravagant wedding banquets where most of the food goes to waste, extreme wedding customs and games in which bridesmaids or the bride and groom are embarrassed, and an unreasonable emphasis on the height of bride prices – these practices have nothing to with traditions anymore and are far removed from what marriage is all about, Zheng writes.

Although many people on social media are not necessarily opposed to the bride price and other customs being changed, they are more angered that other more deep-rooted problems are left untouched: “Why don’t you change the marriage law first?”

For more on this also read:

- Mirror of Time: Chinese Weddings Through the Decades

- Wedding Canceled over Too-Tight Underwear: Chinese Local Wedding Tradition Goes Trending

- China’s ‘Naohun’ Tradition: Are Wedding Games Going Too Far?

- Woman Forced Into Abortion after Boyfriend Cannot Afford 200.000 RMB ‘Bride Price’

- The Problem of Rising Bride Prices in China’s Bare Branch Villages

By Manya Koetse

Featured image via Hunliji.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2021 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Zibo had its BBQ moment. Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine with its special take on malatang. Tourism marketing in China will never be the same again.

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 1, 2024

Since the early post-pandemic days, Chinese cities have stepped up their game to attract more tourists. The dynamics of Chinese social media make it possible for smaller, lesser-known destinations to gain overnight fame as a ‘celebrity city.’ Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine.

During this Qingming Festival holiday, there is one Chinese city that will definitely welcome more visitors than usual. Tianshui, the second largest city in Gansu Province, has emerged as the latest travel hotspot among domestic tourists following its recent surge in popularity online.

Situated approximately halfway along the Lanzhou-Xi’an rail line, this ancient city wasn’t previously a top destination for tourists. Most travelers would typically pass through the industrial city to see the Maiji Shan Grottoes, the fourth largest Buddhist cave complex in China, renowned for its famous rock carvings along the Silk Road.

But now, there is another reason to visit Tianshui: malatang.

Gansu-Style Malatang

Málàtàng (麻辣烫), which literally means ‘numb spicy hot,’ is a popular Chinese street food dish featuring a diverse array of ingredients cooked in a soup base infused with Sichuan pepper and dried chili pepper. There are multiple ways to enjoy malatang.

When dining at smaller street stalls, it’s common to find a selection of skewered foods—ranging from meats to quail eggs and vegetables—simmering in a large vat of flavorful spicy broth. This communal dining experience is affordable and convenient for solo diners or smaller groups seeking a hotpot-style meal.

In malatang restaurants, patrons can usually choose from a selection of self-serve skewered ingredients. You have them weighed, pay, and then have it prepared and served in a bowl with a preferred soup base, often with the option to choose the level of spiciness, from super hot to mild.

Although malatang originated in Sichuan, it is now common all over China. What makes Tianshui malatang stand out is its “Gansu-style” take, with a special focus on hand-pulled noodles, potato, and spicy oil.

An important ingredient for the soup base is the somewhat sweet and fragrant Gangu chili, produced in Tianshui’s Gangu County, known as “the hometown of peppers.”

Another ingredient is Maiji peppercorns (used in the sauce), and there are more locally produced ingredients, such as the black fungi from Qingshui County.

One restaurant that made Tianshui’s malatang particularly famous is Haiying Malatang (海英麻辣烫) in the city’s Qinzhou District. On February 13, the tiny restaurant, which has been around for three decades, welcomed an online influencer (@一杯梁白开) who posted about her visit.

The vlogger was so enthusiastic about her taste of “Gansu-style malatang,” that she urged her followers to try it out. It was the start of something much bigger than she could have imagined.

Replicating Zibo

Tianshui isn’t the first city to capture the spotlight on Chinese social media. Cities such as Zibo and Harbin have previously surged in popularity, becoming overnight sensations on platforms like Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin.

This phenomenon of Chinese cities transforming into hot travel destinations due to social media frenzy became particularly noteworthy in early 2023.

During the Covid years, various factors sparked a friendly competition among Chinese cities, each competing to attract the most visitors and to promote their city in the best way possible.

The Covid pandemic had diverse impacts on the Chinese domestic tourism industry. On one hand, domestic tourism flourished due to the pandemic, as Chinese travelers opted for destinations closer to home amid travel restrictions. On the other hand, the zero-Covid policy, with its lockdowns and the absence of foreign visitors, posed significant challenges to the tourism sector.

Following the abolition of the zero-Covid policy, tourism and marketing departments across China swung into action to revitalize their local economy. China’s social media platforms became battlegrounds to capture the attention of Chinese netizens. Local government officials dressed up in traditional outfits and created original videos to convince tourists to visit their hometowns.

Zibo was the first city to become an absolute social media sensation in the post-Covid era. The old industrial and mining city was not exactly known as a trendy tourist destination, but saw its hotel bookings going up 800% in 2023 compared to pre-Covid year 2019. Among others factors contributing to its success, the city’s online marketing campaign and how it turned its local BBQ culture into a unique selling point were both critical.

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Since 2023, multiple cities have tried to replicate the success of Zibo. Although not all have achieved similar results, Harbin has done very well by becoming a meme-worthy tourist attraction earlier in 2024, emphasizing its snow spectacle and friendly local culture.

By promoting its distinctive take on malatang, Tianshui has emerged as the next city to captivate online audiences, leading to a surge in visitor numbers.

Like with Zibo and Harbin, one particular important strategy used by these tourist offices is to swiftly respond to content created by travel bloggers or food vloggers about their cities, boosting the online attention and immediately seizing the opportunity to turn online success into offline visits.

A Timeline

What does it take to become a Chinese ‘celebrity city’? Since late February and early March of this year, various Douyin accounts started posting about Tianshui and its malatang.

They initially were the main reason driving tourists to the city to try out malatang, but they were not the only reason – city marketing and state media coverage also played a role in how the success of Tianshui played out.

Here’s a timeline of how its (online) frenzy unfolded:

- July 25, 2023: First video on Douyin about Tianshui’s malatang, after which 45 more videos by various accounts followed in the following six months.

- Feb 5, 2024: Douyin account ‘Chuanshuo Zhong de Bozi’ (传说中的波仔) posts a video about malatang streetfood in Gansu

- Feb 13, 2024: Douyin account ‘Yibei Liangbaikai’ (一杯梁白开) posts a video suggesting the “nationwide popularization of Gansu-style malatang.” This video is an important breakthrough moment in the success of Tianshui as a malatang city.

- Feb – March ~, 2024: The Tianshui Culture & Tourism Bureau is visiting sites, conducting research, and organizing meetings with different departments to establish the “Tianshui city + malatang” brand (文旅+天水麻辣烫”品牌) as the city’s new “business card.”

- March 11, 2024: Tianshui city launches a dedicated ‘spicy and hot’ bus line to cater to visitors who want to quickly reach the city’s renowned malatang spots.

- March 13-14, 2024: China’s Baidu search engine witnesses exponential growth in online searches for Tianshui malatang.

- March 14-15, 2024: The boss of Tianshui’s popular Haiying restaurant goes viral after videos show him overwhelmed and worried he can’t keep up. His facial expression becomes a meme, with netizens dubbing it the “can’t keep up-expression” (“烫不完表情”).

The worried and stressed expression of this malatang diner boss went viral overnight.

- March 17, 2024: Chinese media report about free ‘Tianshui malatang’ wifi being offered to visitors as a special service while they’re standing in line at malatang restaurants.

- March 18, 2024: Tianshui opens its first ‘Malatang Street’ where about 40 stalls sell malatang.

- March 18, 2024: Chinese local media report that one Tianshui hair salon (Tony) has changed its shop into a malatang shop overnight, showing just how big the hype has become.

- March 21, 2024: A dedicated ‘Tianshui malatang’ train started riding from Lanzhou West Station to Tianshui (#天水麻辣烫专列开行#).

- March 21, 2024: Chinese actor Jia Nailiang (贾乃亮) makes a video about having Tianshui malatang, further adding to its online success.

- March 30, 2024: A rare occurrence: as the main attraction near Tianshui, the Maiji Mountain Scenic Area announces that they’ve reached the maximum number of visitors and don’t have the capacity to welcome any more visitors, suspending all ticket sales for the day.

- April 1, 2024: Chinese presenter Zhang Dada was spotted making malatang in a local Tianshui restaurant, drawing in even more crowds.

A New Moment to Shine

Fame attracts criticism, and that also holds true for China’s ‘celebrity cities.’

Some argue that Tianshui’s malatang is overrated, considering the richness of Gansu cuisine, which offers much more than just malatang alone.

When Zibo reached hype status, it also faced scrutiny, with some commenters suggesting that the popularity of Zibo BBQ was a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and “empty social spectacle.”

There is a lot to say about the downsides of suddenly becoming a ‘celebrity city’ and the superficiality and fleetingness that comes with these kinds of trends. But for many locals, it is seen as an important moment as they see their businesses and cities thrive.

Even after the hype fades, local businesses can maintain their success by branding themselves as previously viral restaurants. When I visited Zibo a few months after its initial buzz, many once-popular spots marketed themselves as ‘wanghong’ (网红) or viral celebrity restaurants.

For the city itself, being in the spotlight holds its own value in the long run. Even after the hype has peaked and subsided, the gained national recognition ensures that these “trendy” places will continue to attract visitors in the future.

According to data from Ctrip, Tianshui experienced a 40% increase in tourism spending since March (specifically from March 1st to March 16th). State media reports claim that the city saw 2.3 million visitors in the first three weeks of March, with total tourism revenue reaching nearly 1.4 billion yuan ($193.7 million).

There are more ripple effects of Tianshui’s success: Maiji Shan Grottoes are witnessing a surge in visitors, and local e-commerce companies are experiencing a spike in orders from outside the city. Even when they’re not in Tianshui, people still want a piece of Tianshui.

By now, it’s clear that tourism marketing in China will never be the same again. Zibo, Harbin, and Tianshui exemplify a new era of destination hype, requiring a unique selling point, social media success, strong city marketing, and a friendly and fair business culture at the grassroots level.

While Zibo’s success was largely organic, Harbin’s was more orchestrated, and Tianshui learned from both. Now, other potential ‘celebrity’ cities are preparing to go viral, learning from the successes and failures of their predecessors to shine when their time comes.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Media

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

Nothing abnormal about the abnormal MU575 crash?

Published

4 weeks agoon

March 21, 2024

A new report by China’s Civil Aviation Administration has found no abnormalities in the circumstances surrounding the MU5735 incident. Two years after the flight nosedived in mid-air, people are still waiting for clear answers on what led to the devastating crash in Guangxi that killed all 132 people on board.

Two years ago on March 21, China Eastern Airlines flight MU5735 dominated Chinese social media headlines as the Boeing 737 crashed with 132 people on board.

The Boeing 737 was scheduled to fly from the southwestern city of Kunming to Guangzhou. However, it disappeared from radar near the city of Wuzhou, Teng county, just before 14:30 local time, roughly half an hour before its scheduled arrival in Guangzhou.

Around 15:30 local time, news of the crash began to spread on Chinese social media after the real-time flight tracking map Flightradar24 showed the flight dropping some 7000 meters within 120 seconds, leading some to believe it was a “bug.” Two hours later, China Eastern confirmed the crash.

A video showing the plane right before it crashed also went viral on Chinese social media. The footage, taken by cameras belonging to a mining company in Teng county, some 5.8 kilometers from the crash site, shows the plane nosediving from a clear blue sky in a matter of seconds. It plunged more than 20,000 feet in less than a minute.

Security cameras captured the plane nosediving.

A massive week-long search operation in forest-clad, muddy mountains near Wuzhou attracted a lot of attention on social media at the time. While rescue workers were still searching for the second black box, Chinese state media confirmed that all passengers and crew members were killed in the crash.

Search and rescue efforts after the 2022 March 21 crash. Image posted by Caixin on Weibo.

Although a preliminary report about the crash stated that there were no unusual weather circumstances nor abnormal communications before the crash occurred, a final report on the crash still had not come out by late 2022.

This week, on March 20, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) reported further details about the investigation into the MU5735 crash. According to the report:

- All paperwork and qualifications held by the MU5735 flight and cabin crew were in order; they possessed the necessary licenses and certificates, underwent regular health checks, and adhered to standard duty and rest times.

- The aircraft’s maintenance and certifications were up to date, and the maintenance personnel met all requirements.

- No faults were detected with the aircraft itself before takeoff, and there were no abnormal conditions reported, neither with the weather nor radio communication. The loading of the flight met all requirements.

- No anomalies were found in the qualifications of any personnel working at air traffic control, with normal functioning of communication, navigation, and surveillance equipment. There were no abnormalities in radio communication and control commands before the incident.

- The qualifications of relevant personnel at the departure airport on that day met requirements, and facilities and equipment operated normally, following standard procedures.

In summary: no abnormalities were discovered. Compared to an earlier report, this one explicitly ruled out the aircraft itself as the possible cause. The report also stated that the research team will continue to investigate the causes of the incident.

The report on the ‘3・21 incident’ leaves many questions unanswered. The pilot and co-pilot in charge of the plane that day were highly experienced, boasting over 39,000 hours of combined flying experience. The 32-year-old pilot, reportedly following in the footsteps of his father who had also flown for China Eastern, had held the position of captain since early 2018. The 59-year-old co-pilot, allegedly on the brink of retirement, boasted over 30 years of flying experience. Meanwhile, the 26-year-old second co-pilot has been with the airlines for three years.

Despite multiple (foreign media) reports saying that the airplane was deliberately crashed, the latest CAAC update does not mention the possibility of deliberate action leading to the crash at all – and does not even hint at it. In 2015, a Germanwings flight carrying 150 people crashed in the Alps. The incident was later determined to be a deliberate suicidal act by the co-pilot, who had locked the captain out of the cockpit (the captain’s last words were reportedly ‘Open the damn door’). In the case of MU5735, it is unclear what information was gathered from the black boxes or if they were damaged.

A Weibo post by CCTV news about the CAAC report attracted over 108,000 likes and more than 11,000 comments. The majority of commenters express confusion or anger over the report and the lack of any mentions of deliberate actions leading to the crash. Some of the top comments said:

“If everything was normal, then explain if it was caused by people on the plane, or if it was caused by sudden external forces!”

“You still don’t have the contents of the black box??”

“What about any recordings?”

“You might as well have said nothing at all.”

“Another year has passed! I hope, sooner or later, that the truth will come out.”

Elsewhere on Weibo, people also wondered why, after two years, the CAAC came out with such a vague and inconclusive statement.

“There’s no need to be secretive [about what happened]. We should seek truth from facts (..) If not, the damage to the government’s credibility will be even bigger if we keep revisiting the issue every year.”

“I haven’t seen any air crash investigation lasting two years. Whether it’s mechanical failure, weather conditions, or human error, there’s usually a general idea of what has caused it.”

It is unclear when and if there will be more conclusions coming out regarding the ongoing investigation. It might again take until the next anniversary of the deadly incident until another statement is released. For many, it is all just taking too long. One commenter wrote: “There should be an investigation into this investigation.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

Weibo Watch: Burning BMWs

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

A Snowball Effect: How Cold Harbin Became the Hottest Place in China

Jia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Weibo Watch: Frogs in Wells

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight1 month ago

China Insight1 month agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoA Snowball Effect: How Cold Harbin Became the Hottest Place in China

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoJia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

-

China Arts & Entertainment2 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment2 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday