China Digital

Questions Surrounding Tragic Suicide of WePhone Founder Su Xiangmao

The tragic suicide of WePhone app founder Su Xiangmao has been dominating debates on Chinese social media.

Published

7 years agoon

The tragic suicide of WePhone app founder Su Xiangmao has been dominating debates on Chinese social media over the past few days. It is the first time in China that a popular app closes down because its founder committed suicide. Netizens now demand to know the truth behind the story.

“This is the first case in the history of the internet that an app closes down because its founder committed suicide, and that the reason for the suicide is a malicious wife who basically killed him,” ‘Brother News’ (新闻哥), a popular WeChat account, wrote on September 11.

The death of Beijing IT entrepreneur Su Xiangmao (苏享茂), aged 37, indeed has gotten everybody talking on Chinese social media over the past days, making headlines in hundreds of newspapers in mainland China and Taiwan.

It is the dramatic narrative behind the tragedy that has captured Chinese netizens – especially because a large part of this story takes place online.

Su’s suicide note, in which he says his 29-year-old ex-wife blackmailed him into paying her 10 million RMB (±1.5 million US$), was placed on Chinese social media right before his death with her personal details, along with an app notification which also sent users his ex-wife’s phone number.

A suicide note and online revenge

Su Xiangmao is known as the founder of the well-known WePhone software, a Skype-like app that allows users to make phone calls and send text messages to other WePhone users for free. Su Xiangmao jumped to his death from the balcony of his apartment in the early morning of September 7.

Well-known app WePhone.

Shortly before his death, Su published his suicide note on social media which revealed his grievance about the nasty divorce between him and his ex-wife Zhai Xinxin (翟欣欣).

Suicide note placed WePhone founder Su Xiangmao on social media.

See full translation of suicide note here

In his online suicide note, Su says that he had met Zhai through dating site Jiayuan.com and was only briefly married to her when she suddenly changed in behavior. The pair agreed to divorce, which is when the situation turned bitter, the note says.

Zhai allegedly blackmailed Su into paying her over a million dollars and leaving his home in Sanya to her. She intimidated and harassed him, and threatened to take his app offline through her uncle, an influential government official. The situation eventually left Su so exhausted that he decided to sign the divorce papers, losing all of his capital.

In the suicide note, Su says it is “vicious woman” Zhai who actually killed him. He ends the public note with her home address, phone number, and office address.

A notification sent to users of WePhone.

An app notification sent to all users of WePhone said: “The owner of this company is killed by his evil wife Zhai Xinxin [phone number]. WePhone is suspending its services!”

In search of the truth

In the aftermath of the suicide, online discussions continue to play an important role in the search for the truth about what happened to Su, and whether or not Zhai is legally guilty of extortion, with various friends or witnesses coming forward through online media.

Reports by netizens about the case are flooding social media under hashtags such as “Suicide of WePhone Founder”(#wephone创始人自杀). Generally, ex-wife Zhai is seen as the culprit who terrorized Su to such an extent that he eventually saw suicide as his only way out. Some say Zhai even is a professional scammer who received large sums of money from two previous marriages.

Family members of Su have confirmed to Chinese media that in the hours preceding Su’s suicide, he received numerous text messages from Zhai with insults and threats, saying he needed to give her money or else she would report his “illegal income” or “grey business” to the police and make sure he would end up in jail. Screenshots of these messages have been leaked online.

They also say that during the time they were married, Su spent no less than 13 million yuan (nearly 2M$) on Zhai in buying her a house and a Tesla car.

Su Xiangmao and ex-wife Zhai Xixi.

But there are also others, including former classmates of Zhai, who say Zhai was a top student at a prestigious Beijing university and that she is now an ambitious career woman who has no reason to scam others for money.

On September 12, Zhai’s uncle Liu Kejian also stated that he had no part in any situation involving Mr. Su, and that he had never even met him.

And to what extent can the dating site where Su and Zhai met, Jiayuan.com, be held accountable for this tragedy, some wonder. Jiayuan is an online dating platform meant for people who are looking to get married. If Zhai had indeed married twice before and is a professional scammer, then the site should have known this and should have deleted her from their database, according to some netizens’ views.

Jiayuan issued a statement regarding the case, saying the couple were its VIP members. The dating site also said it will assist in any police investigation into Su’s death.

“A second Ma Rong”

To some extent, the WePhone founder case resembles the 2016 divorce case of Wang Baoqiang and Ma Rong. Uncoincidentally, many netizens on Weibo refer to Su’s ex-wife as “a second Ma Rong.”

Ma Rong became the most-hated woman on Chinese social media in 2016 when she cheated on her husband Wang Baoqiang, a popular film star, and later sued him for defamation of character. Many called the young Ma Rong a ‘golddigger’ who only married Wang for his money.

Wang Baoqiang and Ma Rong.

Similar to the current WePhone case, Chinese social media played an important role as the marriage crisis between Wang and his wife unfolded within a matter of days after Wang placed a public message on Weibo accusing his wife of cheating with his agent and announcing the divorce.

The divorce papers that allegedly drove Su to commit suicide.

With every piece of news coming out on the Wang divorce drama, netizens jumped right on it to vent their opinion or to scold Ma Rong. As now, netizens turned into private detectives on the matter, inspecting old photos for clues that Ma Rong was indeed having an affair before or finding out her address and number and publishing them online, along with dozens of other official papers or screenshots serving as evidence in the case.

On September 12, a new website was set up by Chinese netizens (zhaixinxin.com), fully dedicated to the WePhone case and exposing the alleged lies by Zhai.

As with the Ma Rong story, it is probable that this case is not a “today’s newspaper is tomorrow’s fish and chip paper” case; with new facts popping up, the case will inescapably become the trending topic of the day again until netizens are satisfied with the answers they have found.

As one netizen (@猎头老王V) says: “I want to know how the country will deal with the Zhai Xixi case. We need answers so Su Xiangmao can rest in peace.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Thanks to contributors Sidney Wu & Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Arts & Entertainment

Going All In on Short Streaming: About China’s Online ‘Micro Drama’ Craze

For viewers, they’re the ultimate guilty pleasure. For producers, micro dramas mean big profit.

Published

3 weeks agoon

March 26, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

PREMIUM CONTENT

Closely intertwined with the Chinese social media landscape and the fast-paced online entertainment scene, micro dramas have emerged as an immensely popular way to enjoy dramas in bite-sized portions. With their short-format style, these dramas have become big business, leading Chinese production studios to compete and rush to create the next ‘mini’ hit.

In February of this year, Chinese social media started flooding with various hashtags highlighting the huge commercial success of ‘online micro-short dramas’ (wǎngluò wēiduǎnjù 网络微短剧), also referred to as ‘micro drama’ or ‘short dramas’ (微短剧).

Stories ranged from “Micro drama screenwriters making over 100k yuan [$13.8k] monthly” to “Hengdian building earning 2.8 million yuan [$387.8k] rent from micro dramas within six months” and “Couple earns over 400 million [$55 million] in a month by making short dramas,” all reinforcing the same message: micro dramas mean big profits. (Respectively #短剧爆款编剧月入可超10万元#, #横店一栋楼半年靠短剧租金收入280万元#, #一对夫妇做短剧每月进账4亿多#.)

Micro dramas, taking China by storm and also gaining traction overseas, are basically super short streaming series, with each episode usually lasting no more than two minutes.

From Horizontal to Vertical

Online short dramas are closely tied to Chinese social media and have been around for about a decade, initially appearing on platforms like Youku and Tudou. However, the genre didn’t explode in popularity until 2020.

That year, China’s State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT) introduced a “fast registration and filing module for online micro dramas” to their “Key Online Film and Television Drama Information Filing System.” Online dramas or films can only be broadcast after obtaining an “online filing number.”

Chinese streaming giants such as iQiyi, Tencent, and Youku then began releasing 10-15 minute horizontal short dramas in late 2020. Despite their shorter length and faster pace, they actually weren’t much different from regular TV dramas.

Soon after, short video social platforms like Douyin (TikTok) and Kuaishou joined the trend, launching their own short dramas with episodes only lasting around 3 minutes each.

Of course, Douyin wouldn’t miss out on this trend and actively contributed to boosting the genre. To better suit its interface, Douyin converted horizontal-screen dramas into vertical ones (竖屏短剧).

Then, in 2021, the so-called mini-program (小程序) short dramas emerged, condensing each episode to 1-2 minutes, often spanning over 100 episodes.

These short dramas are advertised on platforms like Douyin, and when users click, they are directed to mini-programs where they need to pay for further viewing. Besides direct payment revenue, micro dramas may also bring in revenue from advertising.

‘Losers’ Striking Back

You might wonder what could possibly unfold in a TV drama lasting just two minutes per episode.

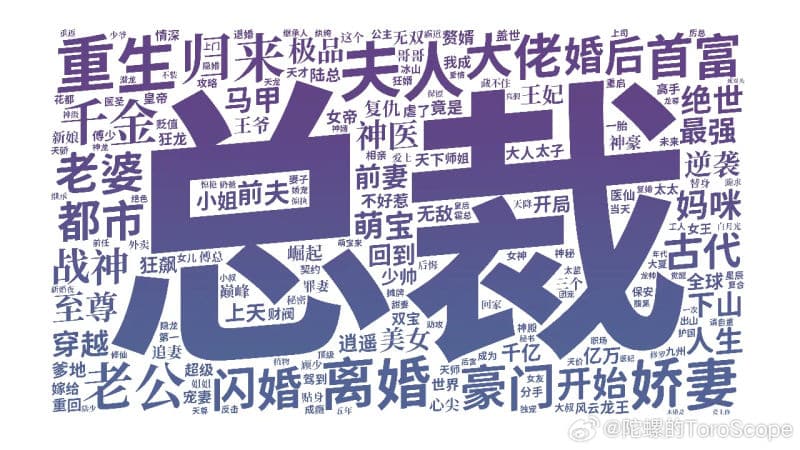

The Chinese cultural media outlet ‘Hedgehog Society’ (刺猬公社) collected data from nearly 6,000 short dramas and generated a word cloud based on their content keywords.

In works targeted at female audiences, the most common words revolve around (romantic) relationships, such as “madam” (夫人) and “CEO” (总裁). Unlike Chinese internet novels from over a decade ago, which often depicted perfect love and luxurious lifestyles, these short dramas offer a different perspective on married life and self-discovery.

According to Hedgehog Society’s data, the frequency of the term “divorce” (离婚) in short dramas is ten times higher than “married” (结婚) or “newlyweds” (新婚). Many of these dramas focus on how the female protagonist builds a better life after divorce and successfully stands up to her ex-husband or to those who once underestimated her — both physically and emotionally.

One of the wordclouds by 刺猬公社.

In male-oriented short dramas, the pursuit of power is a common theme, with phrases like “the strongest in history” (史上最强) and “war god” (战神) frequently mentioned. Another surprising theme is “matrilocal son” (赘婿), the son-in-law who lives with his wife’s family. In China, this term is derogatory, particularly referring to husbands with lower economic income and social status than their wives, which is considered embarrassing in traditional Chinese views. However, in these short dramas, the matrilocal son will employ various methods to earn the respect of his wife’s family and achieve significant success.

Although storylines differ, a recurring theme in these short dramas is protagonists wanting to turn their lives around. This desire for transformation is portrayed from various perspectives, whether it’s from the viewpoint of a wealthy, elite individual or from those with lower social status, such as divorced single women or matrilocal son-in-laws. This “feel-good” sentiment appears to resonate with many Chinese viewers.

Cultural influencer Lu Xuyu (@卢旭宁) quoted from a forum on short dramas, explaining the types of short dramas that are popular: Men seek success and admiration, and want to be pursued by beautiful women. Women seek romantic love or are still hoping the men around them finally wake up. One netizen commented more bluntly: “They are all about the counterattack of the losers (屌丝逆袭).”

The word used here is “diaosi,” a term used by Chinese netizens for many years to describe themselves as losers in a self-deprecating way to cope with the hardships of a competitive life, in which it has become increasingly difficult for Chinese youths to climb the social ladder.

Addicted to Micro Drama

By early 2024, the viewership of China’s micro dramas had soared to 120 million monthly active users, with the genre particularly resonating with lower-income individuals and the elderly in lower-tier markets.

However, short dramas also enjoy widespread popularity among many young people. According to data cited by Bilibili creator Caoxiaoling (@曹小灵比比叨), 64.9% of the audience falls within the 15-29 age group.

For these young viewers, short dramas offer rapid plot twists, meme-worthy dialogues, condensing the content of several episodes of a long drama into just one minute—stripping away everything except the pure “feel-good” sentiment, which seems rare in the contemporary online media environment. Micro dramas have become the ultimate ‘guilty pleasure.’

Various micro dramas, image by Sicomedia.

Even the renowned Chinese actress Ning Jing (@宁静) admitted to being hooked on short dramas. She confessed that while initially feeling “scammed” by the poor production and acting, she became increasingly addicted as she continued watching.

It’s easy to get hooked. Despite criticisms of low quality or shallowness, micro dramas are easy to digest, featuring clear storylines and characters. They don’t demand night-long binge sessions or investment in complex storylines. Instead, people can quickly watch multiple episodes while waiting for their bus or during a short break, satisfying their daily drama fix without investing too much time.

Chasing the gold rush

During the recent Spring Festival holiday, the Chinese box office didn’t witness significant growth compared to previous years. In the meantime, the micro drama “I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother” (我在八零年代当后妈), shot in just 10 days with a post-production cost of 80,000 yuan ($11,000), achieved a single-day revenue exceeding 2 million yuan ($277k). It’s about a college girl who time-travels back to the 1980s, reluctantly getting married to a divorced pig farm owner with kids, but unexpectedly falling in love.

Despite its simple production and clichéd plot, micro dramas like this are drawing in millions of viewers. The producer earned over 100 million yuan ($13 million) from this drama and another short one.

“I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother” (我在八零年代当后妈).

The popularity of short dramas, along with these significant profits, has attracted many people to join the short drama industry. According to some industry insiders, a short drama production team often involves hundreds or even thousands of contributors who help in writing scripts. These contributors include college students, unemployed individuals, and online writers — seemingly anyone can participate.

By now, Hengdian World Studios, the largest film and television shooting base in China, is already packed with crews filming short dramas. With many production teams facing a shortage of extras, reports have surfaced indicating significant increases in salaries, with retired civil workers even being enlisted as actors.

Despite the overwhelming success of some short dramas like “I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother,” it is not easy to replicate their formula. The screenwriter of the time-travel drama, Mi Meng (@咪蒙的微故事), is a renowned online writer who is very familiar with how to use online strategies to draw in more viewers. For many average creators, their short drama production journey is much more difficult and less fruitful.

But with low costs and potentially high returns, even if only one out of a hundred productions succeeds, it could be sufficient to recover the expenses of the others. This high-stakes, cutthroat competition poses a significant challenge for smaller players in the micro drama industry – although they actually fueled the genre’s growth.

As more scriptwriters and short dramas flood the market, leading to content becoming increasingly similar, the chances of making profits are likely to decrease. Many short drama platforms have yet to start generating net profits.

This situation has sparked concerns among netizens and critics regarding the future of short dramas. Given the genre’s success and intense competition, a transformation seems inevitable: only the shortest dramas that cater to the largest audiences will survive.

In the meantime, however, netizens are enjoying the hugely wide selection of micro dramas still available to them. One Weibo blogger, Renmin University Professor Ma Liang (@学者马亮), writes: “I spent some time researching short videos and watched quite a few. I must admit, once you start, you just can’t stop. ”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Tick, Tock, Time to Pay Up? Douyin Is Testing Out Paywalled Short Videos

Is content payment a new beginning for the popular short video app Douyin (China’s TikTok) or would it be the end?

Published

5 months agoon

November 18, 2023

The introduction of a Douyin novel feature, that would enable content creators to impose a fee for accessing their short video content, has sparked discussions across Chinese social media. Although the feature would benefit creators, many Douyin users are skeptical.

News that Chinese social media app Douyin is rolling out a new feature which allows creators to introduce a paywall for their short video content has triggered online discussions in China this week.

The feature, which made headlines on November 16, is presently in the testing phase. A number of influential content creators are now allowed to ‘paywall’ part of their video content.

Douyin is the hugely popular app by Chinese tech giant Bytedance. TikTok is the international version of the Chinese successful short video app, and although they’re often presented as being the same product, Douyin and Tiktok are actually two separate entities.

In addition to variations in content management and general usage, Douyin differs from TikTok in terms of features. Douyin previously experimented with functionalities such as charging users for accessing mini-dramas on the platform or the ability to tip content creators.

The pay-to-view feature on Douyin would require users to pay a certain fee in Douyin coins (抖币) in order to view paywalled content. One Douyin coin is equivalent to 0.1 yuan ($0,014). The platform itself takes 30% of the income as a service charge.

According to China Securities Times or STCN (证券时报网), Douyin insiders said that any short video content meeting Douyin’s requirements could be set as “pay-per-view.”

Creators, who can set their own paywall prices, should reportedly meet three criteria to qualify for the pay-to-view feature: their account cannot have any violation records for a period of 90 days, they should have at least 100,000 followers, and they have to have completed the real-name authentication process.

On Douyin and Weibo, Chinese netizens express various views on the feature. Many people do not think it would be a good idea to charge money for short videos. One video blogger (@小片片说大片) pointed out the existing challenge of persuading netizens to pay for longer videos, let alone expecting them to pay for shorter ones.

“The moment I’d need to pay money for it, I’ll delete the app,” some commenters write.

This statement appears to capture the prevailing sentiment among most internet users regarding a subscription-based Douyin environment. According to a survey conducted by the media platform Pear Video, more than 93% of respondents expressed they would not be willing to pay for short videos.

An online poll by Pear Video showed that the majority of respondents would not be willing to pay for short videos on Douyin.

“This could be a breaking point for Douyin,” one person predicts: “Other platforms could replace it.” There are more people who think it would be the end of Douyin and that other (free) short video platforms might take its place.

Some commenters, however, had their own reasons for supporting a pay-per-view function on the platform, suggesting it would help them solve their Douyin addiction. One commenter remarked, “Fantastic, this might finally help me break free from watching short videos!” Another individual responded, “Perhaps this could serve as a remedy for my procrastination.”

As discussions about the new feature trended, Douyin’s customer service responded, stating that it would eventually be up to content creators whether or not they want to activate the paid feature for their videos, and that it would be up to users whether or not they would be interested in such content – otherwise they can just swipe away.

Another social media user wrote: “There’s only one kind of video I’m willing to pay for, and it’s not on Douyin.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

Weibo Watch: Burning BMWs

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

A Snowball Effect: How Cold Harbin Became the Hottest Place in China

Jia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Weibo Watch: Frogs in Wells

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight1 month ago

China Insight1 month agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoA Snowball Effect: How Cold Harbin Became the Hottest Place in China

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoJia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

-

China Arts & Entertainment2 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment2 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Kenny

September 15, 2017 at 1:00 am

http://tech.ifeng.com/a/20170911/44679039_0.shtml

the above news site (chinese) provide a few photos allegedly the receipt records (in chinese yuan) of his wife, pretty insane if you ask me, according to some other photos allegedly known as their chat history posted by Su Xiangmao on his own weibo/google+, he’s a pretty honest guy who lend her enormous financial support while the wife is just the definition of being venomous without a bottom line. According to the chat history, he notably killed himself because his stock has fallen 20% and wife still demands about $2million USD (compensation for spiritual damages of divorce and all the properties she bought in Sanya,Hainan Island) in a voice threatening to get him imprisoned if not complied. I heard the guy also had history of being fined by the government for operating WePhone under the gray zone of Chinese Law, and this is still the case before his suicide so that’s another allegation his wife can use to gain advantage against him. Meanwhile his entire self-declared net worth was just about $1,006,849 USD, Di Xinxin(wife) also forces him to comply with her long-term payment contract of 2 million with the threat of using her strong family relationship in the local police station (her uncle known as the head of public security court) to get him imprisoned…

So much pressure to take for an honest guy, a guy who was willing to let his wife spend millions of USD without a single concern, finally couldn’t take it all… depressing story.

eru

September 28, 2017 at 5:09 pm

He deserved that, that app is a fking defraud platform(been reported by many countries). I sympathize this woman cuz she’s being under cyber abused (which is Su had planned and incited) in China, a fking gross man chauvinist country.