China Arts & Entertainment

Rotten Girls: China’s Thriving Online Boys’ Love Culture

It is an online subculture that has been around for more than a decade, and it is not likely to die out any time soon.

Published

4 years agoon

They are mocked, hated, and misunderstood, yet China’s so-called ‘Rotten Girls’ are at the core of an online subculture that has been thriving for years.

This is the “WE…WEI…WHAT?” column by Manya Koetse, original publication in German by Goethe Institut China (forthcoming), see Goethe.de: WE…WEI…WHAT? Manya Koetse erklärt das chinesische Internet.

China’s ever-buzzing social media sphere sees trends, topics, and movements pop up every single day and then fade away quickly when their novelty is gone. But there are some trends that turn into something bigger, bringing forth communities and online subcultures that keep on thriving for years, with the participants building their own spaces in the online environment.

One such space belongs to those who, with some self-mockery, define as “Rotten Girls” (fǔnǚ 腐女), derived from the Japanese fujoshi. In the Chinese context, ‘Rotten Girls’ are young women with a passion for fictional stories, drama series, and manga (comic books) featuring gay male erotica and romantic relationships called ‘yaoi.’

‘Rotten girls’ do not just consume these stories, primarily written by and for women, they also create and share them with others to discuss.

In Chinese, the gay erotica known as yaoi is also called ‘danmei’ (耽美) or ‘BL’ (for ‘Boys’ Love’) – all umbrella terms for contents of male-male homoerotic fiction. The genre plays a major role in various corners of the Chinese internet. It is an online subculture that has been around for more than a decade, and it is not likely to die out any time soon.

Media and technology both play a big part in the sharing of fǔnǚ fantasies. These fantasies can range from boys holding hands to more pornographic ones, but the main point of the imaginary is love and intimacy (Galbraith 2011, 213).

Always Another BL Trend

There is always something different trending in the world of Rotten Girls. This summer, for example, the release of the Japanese 18+ games ‘Lkyt’ by BL game brand Parade received a lot of attention. A previous game by Parade, ‘Room No. 9,’ is also still popular among BL fans in China. The game revolves around two young men, long-time friends, who get locked inside a room where they are subjected to a behavioral analysis experiment. The two have to make some taunting decisions, including possibly being forced into sexual activity with each other, in order to make it out alive.

Another major topic that went trending within the Rotten Girls community some years ago, even attracting the attention of western news media, was the British crime drama Sherlock. Many Chinese viewers in the BL scenes were convinced that detective Sherlock Holmes (played by Benedict Cumberbatch) and his sidekick Watson (Martin Freeman) were not just professional partners, but a romantic couple. This practice of imagining a relationship between two characters is also known as ‘CP,’ an abbreviation for “coupling” or “character pairing.”

The ambiguous relationship between Holmes and Watson – and the very fact that they are not explicitly homosexual – suits the fantasies harbored by China’s fǔnǚ. There are countless examples of how BL fans photoshopped Sherlock images into homoerotic scenes, making up their own stories and endlessly discussing the relationship between Holmes and Watson.

Fanart: Holmes and Watson share a passionate kiss

BL fans are active in various online spaces. There are Rotten Girls communities on Chinese literature websites, discussion boards, and on ACG-focused platforms such as Bilibili (ACG is a popular abbreviation of “Anime, Comic and Games”). Boys’ Love is practically everywhere: short stories, web novels, manga, anime, games, and series are all actively created, consumed, and shared within the BL fandom.

The Chinese Jinjiang Literature City site (1998) is one of the earliest and most influential websites for the danmei genre, where some top channels receive millions of clicks. The Chinese web novel author ‘Priest’ is among one of the most successful authors (some translations in English can be found here).

But besides the special BL fiction forums, there are also many fǔnǚ accounts on the more mainstream social media platforms such as WeChat and Weibo. Under Weibo hashtags such as “Fǔnǚ Daily” (#腐女日常#), “BL Webtoons” (#bl条漫#), “BL Manga” (#bl漫画#), “Original Danmei” (#原创耽美#), and many more, Rotten Girls discuss their favorite danmei works and the latest news on a daily basis.

Although the Rotten Girls have been increasing their sphere of influence, it hasn’t been without controversy. Not only are they often looked down upon for their love for male homoeroticism, some LGBT people also criticize them for silencing the voices of actual gay men or erasing real-life gay experiences.

From Japanese Toy Boys to Chinese Danmei

Where did this all begin? China’s BL subculture finds it roots in Japan. The popularity of danmei came up with the growing influence of Japanese popular culture in China.

In the early 1990s, Japanese manga and anime titles started flooding the Chinese market, often as unauthorized (pirated) copies. With this wave of Japanese entertainment products hitting the Chinese market, there were also those belonging to the genre of BL.

In Japanese fiction and manga, the theme of male-male romance intended for a female audience emerged as early as the 1970s but did not really rise to popularity until the early 1990s, when Japanese mainstream media saw a ‘gay boom’ and representations of male homosexuality became in vogue.

The year 1993 truly was a ‘gay year’ in the Japanese media and entertainment industry. In “Producing Gayness” (1997), Sho Ogawa describes how one Japanese magazine even offered readers a “Gay Toybox”: full color paper gay dolls to cut out, including matching clothes from jackets to sports uniforms and even leather bondage gear. Instructions that came with the paper dolls encouraged readers to play with them, “give them a lovely name” and “imagine a campus love affair” between them.

It was also in this same year of 1993 that many Chinese young women first discovered the genre of Japanese Boys’ Love, mainly through the dissemination of pirate manga, novels, and magazines in Chinese bookstores.

Throughout the years, the Chinese genre of danmei has become much more than just an imported entertainment genre from Japan, and it is also somewhat different from the subgenre of ‘slash fiction’ in the West.

Danmei literally means “to indulge in beauty,” and it has developed its own characteristics, taking a predominantly literary form while also strongly resonating with Japanese visual culture (Madill et al 2018, 5). Since the first Chinese BL-focused monthly magazine appeared in 1999, the genre has mixed with various local and other foreign media and celebrity cultures (e.g. that of South Korean and Thailand), and has become a truly Chinese fan culture phenomenon (Chen 2017, 7; Yang & Xu 2017, 3).

Safe, Subversive, and Pure Love

Those outside the danmei subculture often wonder what makes ‘Boys’ Love’ so appealing to so many young women. There are various explanations and interpretations of why female fans enjoy writing and reading about male homoeroticism.

Chen Xin, who studied the topic of Boys’ Love at the University of British Columbia, offers “safety” as one explanation for the popularity of danmei, as it gives its readers, mostly straight women, the freedom to fantasize in a way that is removed from their own romantic lives. This is also reiterated by other scholars, who argue that BL provides a safe fantasy where female fans can avoid the objectification of women while exploring the boundaries of their own sexuality.

The concept of ‘pure love’ is one of the funü’s greatest attraction to BL. According to them, it is the most romantic type of love because it transcends the boundaries of gender. The male protagonists in these stories do not identify as gay, but fall in love with other men nevertheless. “It doesn’t matter if you are male or female, I just love you” and “It’s not that I am gay, I just love a man” are classic sentences within Rotten Girls’ fiction (Dai 2013, 34).

Zhang Chunyu (2016) also highlights the genre as an outlet for female writers and readers to explore sexuality and pleasure in a “subversive” way. Rotten girls position males as the objects of female desire, and in doing so, they challenge traditional gender stereotypes and appreciate gender fluidity.

China’s Rotten Girls subculture is also ‘subversive’ in another way. Because of its focus on homosexuality and eroticism, danmei fandom is subject to online censorship. According to China’s cyberspace regulations, online content should adhere to the “correct political direction” and “strive to disseminate contemporary Chinese values.” Over the past few years, there have been various moments when displays of homosexuality were targeted by censors.

An anti-pornography campaign of 2014 resulted in the shutdown of hundreds of websites and social media accounts. Throughout the years, dozens of danmei authors have been arrested and many sites were closed or deleted for creating and distributing homoerotic content (Chen 2017, 9; Madill et al 2018, 6; Zhang 2016, 250).

Despite the strict internet control, fǔnǚ and BL content are still going strong. In order to circumvent censorship, the words and images used are often coded or nuanced enough not to get deleted – but BL fans will still understand and enjoy the subtext.

Over the past years, China’s Rotten Girls have grown from a niche community to a force to reckon with on the Chinese internet. They have become a phenomenon that is often discussed in the media and is even researched by many academics.

“We’ve become professionals now,” one ‘Rotten Girl’ joked on Weibo recently.

Another commenter replied that the rise and possible fall of the danmei community is, eventually, intrinsically linked to how much room is given by China’s internet regulators. Although the past decade has demonstrated that Rotten Girls are not easily scared away by censorship and shutdowns, their future eventually does depend on the online accessibility to BL media and forums.

“If there is no relaxed online environment, it doesn’t matter how professional we are,” one commenter writes: “We might come to a standstill.”

What the future will hold for China’s Rotten Girls remains to be seen. Whether met with controversy or censorship, for now it seems impossible to put the Rotten Girls back into the closet they came from.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

This text was written for Goethe-Institut China under a CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE license (Creative Commons) as part of a monthly column in collaboration with What’s On Weibo.

References

Chen, Xin. 2017. “Boys’ Love (Danmei) Fiction On The Chinese Internet: Wasabi Kun, The Bl Forum Young Nobleman Changpei, And The Development Of An Online Literary Phenomenon.” MA Thesis, University of British Colombia https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Boys%27-Love-(Danmei)-fiction-on-the-Chinese-internet-Chen/63e7b494653bc1d849461b7a8f3d57aad05be452 [Aug 30, 2020].

Cohane (阿扣-绝赞爬墙中). 2020. “第二章 中国内地BL文化发展历史整理 [Part Two: A History of Development of Mainland China BL Culture Development]” (In Chinese). Weibo Article, Aug 8, https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309404536531036799045 [Aug 26 2020].

Dai, Fei 戴非. 2013. “腐女心理 [Funu Psychology]” (In Chinese). 大众心里学 Popular Psychology (12): 34-35.

Galbraith, Patrick W. 2011. “Fujoshi: Fantasy Play and Transgressive Intimacy among “Rotten Girls” in Contemporary Japan.” Signs 37 (1): 211-232.

Larigakis, Sophia. 2017. “Boys’ Love: The Gay Erotica Taking China by Storm.” Sophialarigakis.com, Nov 6 https://www.sophialarigakis.com/writing/boys-love-china [Aug 29, 2020].

Madill, A., Zhao, Y. and Fan, L. 2018. “Male-male marriage in Sinophone and Anglophone Harry Potter Danmei and Slash.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 9 (5): 418-434.

Ogawa, Sho. 2017. “Producing Gayness: The 1990s “Gay Boom” in Japanese Media.” PhD Dissertation, University of Kansas.

Yang, Ling and Yanrui Xi. 2016. “Danmei, Xianqing, and the making of a queer online public sphere in China.” Communication and the Public 1 (2): 251-256.

Yang, Ling and Yanrui Xu. 2017. “Chinese Danmei Fandom and Cultural Globalization from Below.” In: Lavin, Maud, Ling Yang, and Jing Jamie Zhao (eds). 2017. Boys’ Love, Cosplay, and Androgynous Idols – Queer Fan Cultures in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, page 3-20.

Zhang, Chunyu. 2016. “Loving Boys Twice as Much: Chinese Women’s Paradoxical Fandom of “Boys’ Love” Fiction.” Women’s Studies In Communication 39 (3): 249–267.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Arts & Entertainment

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Online reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among Chinese netizens.

Published

1 week agoon

April 18, 2024

The recent marriage announcement of the renowned Chinese calligrapher/painter Fan Zeng and Xu Meng, a Beijing TV presenter 50 years his junior, has sparked online discussions about the life and work of the esteemed Chinese artist. Some netizens think Fan lacks the integrity expected of a Chinese scholar-artist.

Recently, the marriage of a 86-year-old Chinese painter to his bride, who is half a century younger, has stirred conversations on Chinese social media.

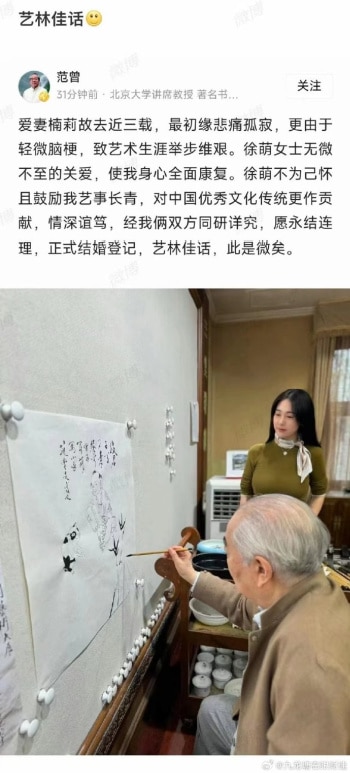

The story revolves around renowned Chinese artist, calligrapher, and scholar Fan Zeng (范曾, 1938) and his new spouse, Xu Meng (徐萌, 1988). On April 10, Fan announced their marriage through an online post accompanied by a picture.

In the picture, Fan is seen working on his announcement in calligraphic form.

Fan Zeng announces his marriage on Chinese social media.

In his writing, Zeng shares that the passing of his late wife, three years ago, left him heartbroken, and a minor stroke also hindered his work. He expresses gratitude for Xu Meng’s care, which he says led to his physical and mental recovery. Zeng concludes by expressing hope for “everlasting harmony” in their marriage.

Fan Zeng is a calligrapher and poet, but he is primarily recognized as a contemporary master of traditional Chinese painting. Growing up in a well-known literary family, his journey in art began at a young age. Fan studied under renowned mentors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, including Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Jiang Zhaohe, and Li Kuchan.

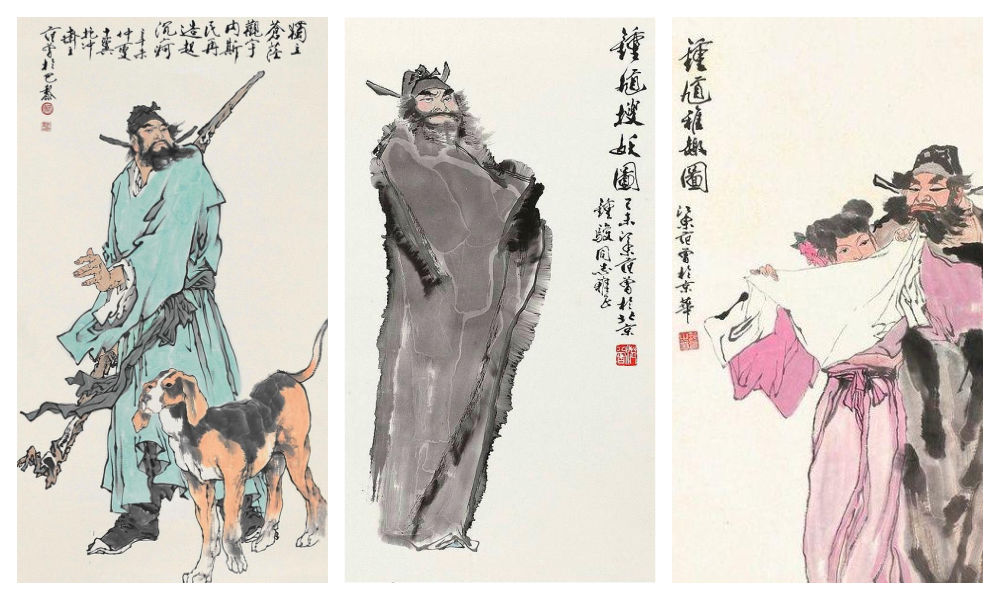

Fan gained global acclaim for his simple yet vibrant painting style. He resided in France, showcased his work in numerous exhibitions worldwide, and his pieces were auctioned at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the 1980s.[1] One of Fan’s works, depicting spirit guardian Zhong Kui (钟馗), was sold for over 6 million yuan (828,000 USD).

Zhong Kui in works by Fan Zeng.

In his later years, Fan Zeng transitioned to academia, serving as a lecturer at Nankai University in Tianjin. At the age of 63, he assumed the role of head of the Nankai University Museum of Antiquities, as well as holding various other positions from doctoral supervisor to honorary dean.

By now, Fan’s work has already become part of China’s twentieth-century art history. Renowned contemporary scholar Qian Zhongshu once remarked that Fan “excelled all in artistic quality, painting people beyond mere physicality.”

A questionable “role model”

Fan’s third wife passed away in 2021. Later, he got to know Xu Meng, a presenter at China Traffic Broadcasting. Allegedly, shortly after they met, he gifted her a Ferrari, sparking the beginning of their relationship.

A photo of Xu and her Hermes Birkin 25 bag has also been making the rounds on social media, fueling rumors that she is only in it for the money (the bag costs more than 180,000 yuan / nearly 25,000 USD).

On Weibo, reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among netizens. Despite Fan’s reputation as a prominent philanthropist, many perceive his recent marriage as yet another instance of his lack of integrity and shamelessness.

Fan Zeng and Xu Meng. Image via Weibo.

One popular blogger (@好时代见证记录者) sarcastically wrote:

“Warm congratulations to the 86-year-old renowned contemporary erudite scholar and famous calligrapher Fan Zeng, born in 1938, on his marriage to Ms Xu Meng, a 50 years younger 175cm tall woman who is claimed to be China’s number one golden ratio beauty. Mr Fan Zeng really is a role model for us middle-aged greasy men, as it makes us feel much less uncomfortable when we’re pursuing post-90s youngsters as girlfriends and gives us an extra shield! Because if contemporary Confucian scholars [like yourself] are doing this, then we, as the inheritors of Confucian culture, can surely do the same!“

Various people criticize the fact that Xu Meng is essentially just an aide to Fan, as she can often be seen helping him during his work. One commenter wrote: “Couldn’t he have just hired an assistant? There’s no need to turn them into a bed partner.”

Others think it’s strange for a supposedly scholarly man to be so superficial: “He just wants her for her body. And she just wants him for his inheritance.”

“It’s so inappropriate,” others wrote, labeling Fan as “an old bull grazing on young grass” (lǎoniú chī nèncǎo 老牛吃嫩草).

Fan is not the only well-known Chinese scholar to ‘graze on young grass.’ The famous Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), now 101 years old, also shares a 48-year age gap with his wife Weng Fen (翁帆). Fan, who is a friend of Yang’s, previously praised the love between Yang and Weng, suggesting that she kept him youthful.

Older photo posted on social media, showing Fan attending the wedding ceremony of Yang Zhenning and his 48-year-younger partner Weng Fen.

Some speculate that Fan took inspiration from Yang in marrying a significantly younger woman. Others view him as hypocritical, given his expressions of heartbreak over his previous wife’s passing, and how there’s only one true love in his lifetime, only to remarry a few years later.

Many commenters argue that Fan Zeng’s conduct doesn’t align with that of a “true Confucian scholar,” suggesting that he’s undeserving of the praise he receives.

“Mr. Wang from next door”

In online discussions surrounding Fan Zeng’s recent marriage, more reasons emerge as to why people dislike him.

Many netizens perceive him as more of a money-driven businessman rather than an idealistic artist. They label him as arrogant, critique his work, and question why his pieces sell for so much money. Some even allege that the only reason he created a calligraphy painting of his marriage announcement is to profit from it.

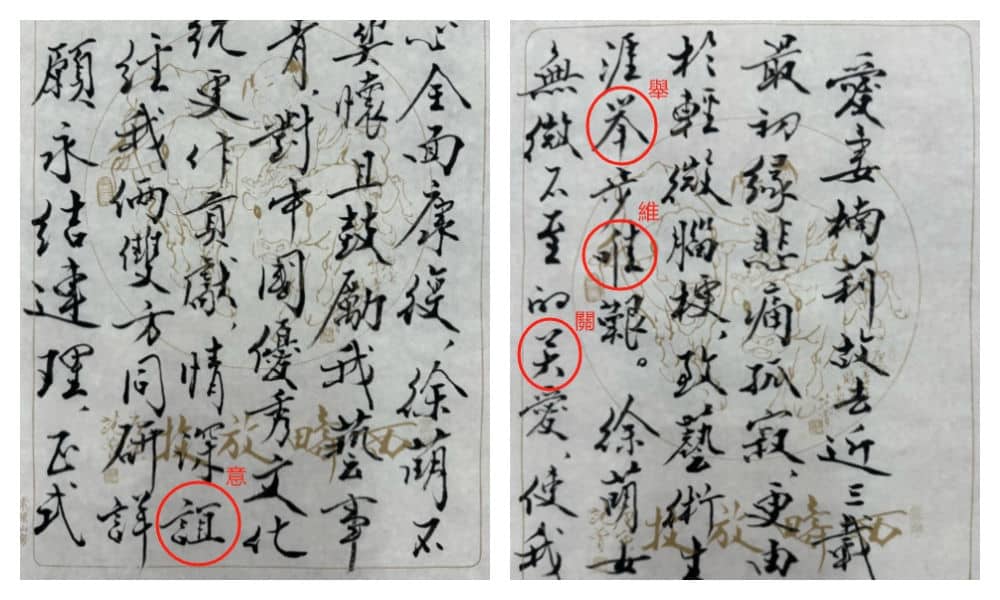

Others cast doubt on his status as a Chinese calligraphy ‘grandmaster,’ noting that his calligraphy style is not particularly impressive and may contain typos or errors. His wedding announcement calligraphy appears to blend traditional and simplified characters.

Netizens have pointed out what looks like errors or typos in Fan’s calligraphy.

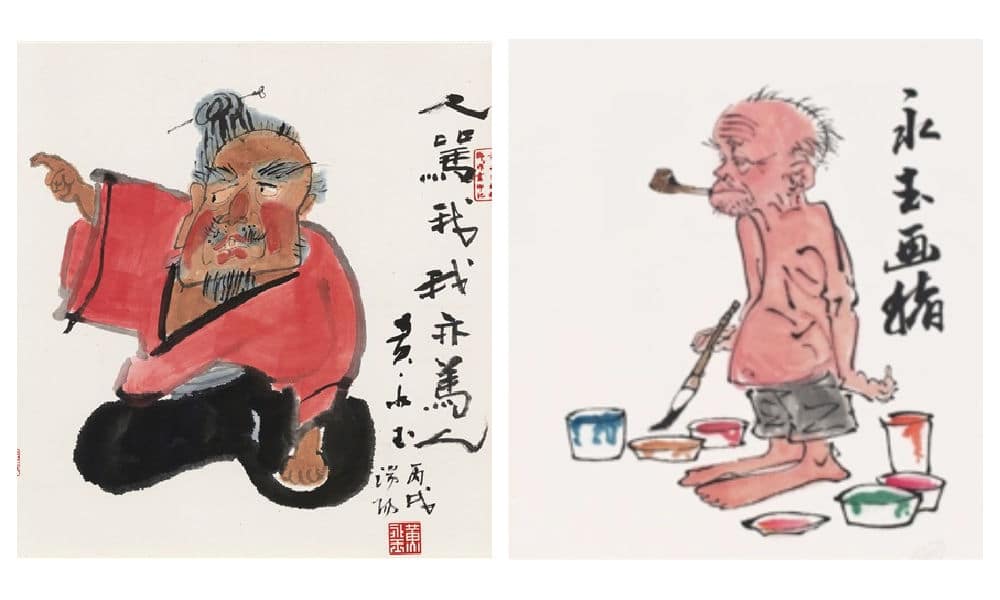

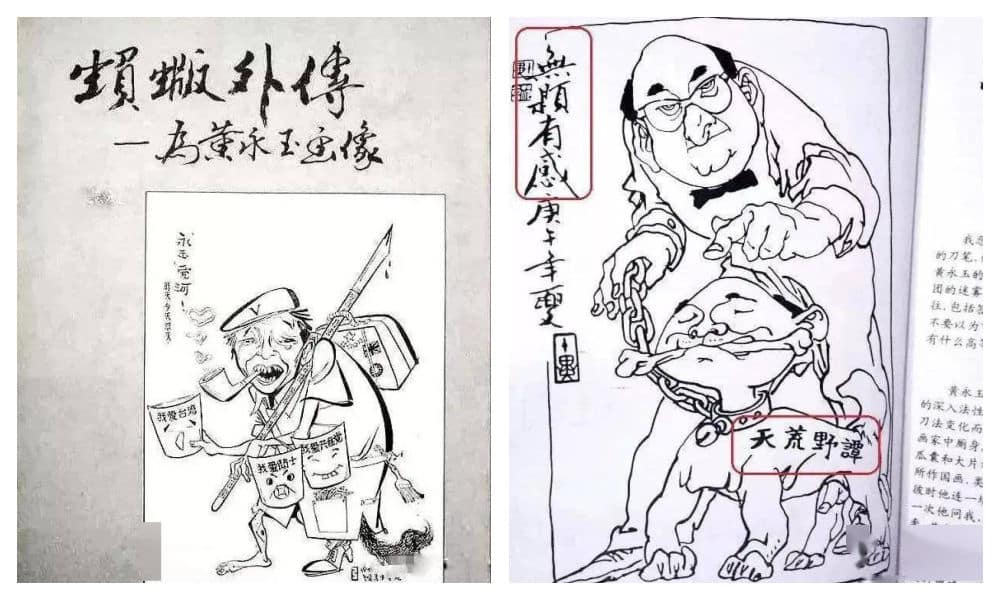

Another source of dislike stems from his history of disloyalty and his feud with another prominent Chinese painter, Huang Yongyu (黄永玉). Huang, who passed away in 2023, targeted Fan Zeng in some of his satirical paintings, including one titled “When Others Curse Me, I Also Curse Others” (“人骂我,我亦骂人”). He also painted a parrot, meant to mock Fan Zeng’s unoriginality.

Huang Yongyu made various works targeting Fan Zeng.

In retaliation, Fan produced his own works mocking Huang, sparking an infamous rivalry in the Chinese art world. The two allegedly almost had a physical fight when they ran into each other at the Beijing Hotel.

Fan Zeng mocked Huang Yongyu in some of his works.

Fan and Huang were once on good terms though, with Fan studying under Huang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Through Huang, Fan was introduced to the renowned Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文, 1902-1988), Huang’s first cousin and lifelong friend. As Shen guided Fan in his studies and connected him with influential figures in China’s cultural circles, their relationship flourished.

However, during the Cultural Revolution, when Shen was accused of being a ‘reactionary,’ Fan Zeng turned against him, even going as far as creating big-character posters to criticize his former mentor.[2] This betrayal not only severed the bond between Shen and Fan but also ended Fan’s friendship with Huang, and it is still remembered by people today.

Fan Zeng’s behavior towards another former mentor, the renowned painter Li Kuchan (李苦禪, 1899-1983), was also controversial. Once Fan gained fame, he made it clear that he no longer respected Li as his teacher. Li later referred to Fan as “a wolf in sheep’s clothes,” and apparently never forgave him. Although the exact details of their falling out remain unclear, some blame Fan for exploiting Li to further his own career.

There are also some online commenters who call Fan Zeng a “Mr Wang from next door” (隔壁老王), a term jokingly used to refer to the untrustworthy neighbor who sleeps with one’s wife. This is mostly because of the history of how Fan Zeng met his third wife.

Fan’s first wife was the Chinese female calligrapher Lin Xiu (林岫), who came from a wealthy family. During this marriage, Fan did not have to worry about money and focused on his artistic endeavours. The two had a son, but the marriage ended in divorce after a decade. Fan’s second wife was fellow painter Bian Biaohua (边宝华), with whom he had a daughter. It seems that Bian loved Fan much more than he loved her.

It is how he met his third wife that remains controversial to this day. Nan Li (楠莉), formerly named Zhang Guiyun (张桂云), was married to performer Xu Zunde (须遵德). Xu was a close friend of Fan, and helped him out when Fan was still poor and trying to get by while living in Beijing’s old city center.

Wanting to support Fan’s artistic talent, Xu let Fan Zeng stay over, supported him financially, and would invite him for meals. Little did he know that while Xu was away to work, Fan enjoyed much more than meals alone; Fan and Xu’s wife engaged in a secret decade-long affair.

When the affair was finally exposed, Xu Zunde divorced his wife. Still, they would use his house to meet and often locked him out. Three years later, Nan Li officially married Fan Zeng. Xu not only lost his wife and friend but also ended up finding his house emptied, his two sons now bearing Fan’s surname.

When Nan Li passed away in 2021, Fan Zeng published an obituary that garnered criticism. Some felt that the entire text was actually more about praising himself than focusing on the life and character of his late wife, with whom he had been married for forty years.

Fan Zeng and his four wives

An ‘old pervert’, a ‘traitor’, a ‘disgrace’—there are a lot of opinions circulating about Fan that have come up this week.

Despite the negativity, a handful of individuals maintain a positive outlook. A former colleague of Xu Meng writes: “If they genuinely like each other, age shouldn’t matter. Here’s to wishing them a joyful marriage.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Song, Yuwu. 2014. Biographical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China. United Kingdom: McFarland & Company, 76.

[2]Xu, Jilin. 2024. “Xu Jilin: Are Shen Congwen’s Tears Related to Fan Zeng?” 许纪霖:沈从文的泪与范曾有关系吗? The Paper, April 15. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_27011031. Accessed April 17, 2024.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

How a senior activity park in Chengdu was ‘Disneyfied’ and became a viral hotspot.

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 12, 2024

How did a common park turn into a buzzing hotspot? By mixing online trends with real-life fun, blending foreign styles with local charm, and adding a dash of humor and absurdity, Chengdu now boasts its very own ‘Chengdu Disney’. We explain the trend.

– By Manya Koetse, co-authored by Ruixin Zhang

Have you heard about Chengdu Disney yet? If not, it’s probably unlike anything you’d imagine. It’s not actually a Disney theme park opening up in Chengdu, but it’s one of the city’s most viral hotspots these days.

What is now known as ‘Chengdu Disney’ all over the Chinese internet is actually a small outdoor park in a residential area in Chengdu’s Yulin area, which also serves as the local senior fitness activity center.

Crowds of young people are coming to this area to take photos and videos, hang out, sing songs, cosplay, and be part of China’s internet culture in an offline setting.

Once Upon a Rap Talent Show

The roots of ‘Chengdu Disney’ can be traced back to the Chinese hip-hop talent show The Rap of China (中国新说唱), where a performer named Nuomi (诺米), also known as Lodmemo, was eliminated by Chinese rapper Boss Shady (谢帝 Xièdì), one of the judges on the show.

Nuomi felt upset about the elimination and a comment made by his idol mentor, who mistakenly referred to a song Nuomi made for his ‘grandma’ instead of his grandfather. His frustration led to a viral livestream where he expressed his anger towards his participation in The Rap of China and Boss Shady.

However, it wasn’t only his anger that caught attention; it was his exaggerated way of speaking and mannerisms. Nuomi, with his Sichuan accent, repeatedly inserted English phrases like “y’know what I’m saying” and gestured as if throwing punches.

His oversized silver chain, sagging pants, and urban streetwear only reinforce the idea that Nuomi is trying a bit too hard to emulate the fashion style of American rappers from the early 2000s, complete with swagger and street credibility.

Lodmemo emulates the style of American rappers in the early 2000s, and he has made it his brand.

Although people mocked him for his wannabe ‘gangsta’ style, Nuomi embraced the teasing and turned it into an opportunity for fame.

He decided to create a diss track titled Xiè Tiān Xièdì 谢天谢帝, “Thank Heaven, Thank Emperor,” a word joke on Boss Shady’s name, which sounds like “Shady” but literally means ‘Thank the Emperor’ in Chinese. A diss track is a hip hop or rap song intended to mock someone else, usually a fellow musician.

In the song, when Nuomi disses Boss Shady (谢帝 Xièdì), he raps in Sichuan accent: “Xièdì Xièdì wǒ yào diss nǐ [谢帝谢帝我要diss你].” The last two words, namely “diss nǐ” actually means “to diss you” but sounds exactly like the Chinese word for ‘Disney’: Díshìní (迪士尼). This was soon picked up by netizens, who found humor in the similarity; it sounded as if the ‘tough’ rapper Nuomi was singing about wanting to go to Disney.

Nuomi and his diss track, from the music video.

Nuomi filmed the music video for this diss track at a senior activity park in Chengdu’s Yulin subdistrict. The music video went viral in late March, and led to the park being nicknamed the ‘Chengdu Disney.’

The particular exercise machine on which Nuomi performed his rap quickly became an iconic landmark on Douyin, as everyone eagerly sought to visit, sit on the same see-saw-style exercise machine, and repeat the phrase, mimicking the viral video.

What began as a homonym led to people ‘Disneyfying’ the park itself, with crowds of visitors flocking to the park, some dressed in Disney-related costumes.

This further developed the concept of a Chengdu ‘Disney’ destination, turning the park playground into the happiest place in Yulin.

Chengdu: China’s Most Relaxed Hip Hop Hotspot

Chengdu holds a special place in China’s underground hip-hop scene, thanks to its vibrant music culture and the presence of many renowned Chinese hip-hop artists who incorporate the Sichuan dialect into their songs and raps.

This is one reason why this ‘Disney’ meme happened in Chengdu and not in any other Chinese city. But beyond its musical significance, the playful spirit of the meme also aligns with Chengdu’s reputation for being an incredibly laid-back city.

In recent years, the pursuit of a certain “relaxed feeling” (sōngchígǎn 松弛感) has gained popularity across the Chinese internet. Sōngchígǎn is a combination of the word for “relaxed,” “loose” or “lax” (松弛) and the word for “feeling” (感). Initially used to describe a particular female aesthetic, the term evolved to represent a lifestyle where individuals strive to maintain a relaxed demeanor, especially in the face of stressful situations.

🌟 Attention!

For 11 years, What’s on Weibo has remained a 100% independent blog, fueled by my passion to write about China’s digital culture and online trends. Over a year ago, we introduced a soft paywall to ensure the sustainability of this platform. I’m grateful to all our loyal readers who’ve subscribed since 2022. Your support has been invaluable. But we need more subscribers to continue our work. If you appreciate our content and want to support independent China reporting, please consider becoming a subscriber. Your support keeps What’s on Weibo going strong!

The concept gained traction online in mid-2022 when a Weibo user shared a story of a family remaining composed when their travel plans were unexpectedly disrupted due to passport issues. Their calm and collected response inspired the adoption of the “relaxed feeling” term (also read here).

Central to embodying this sense of relaxation is being unfazed by others’ opinions and avoiding unnecessary stress or haste out of fear of judgment.

Nowadays, Chinese cities aim to foster this sense of sōngchígǎn. Not too long ago, there were many hot topics suggesting that Chengdu is the most sōngchí 松弛, the most relaxed city in China.

This sentiment is reflected in the ‘Chengdu Disney’ trend, which both pokes fun at a certain hip-hop aesthetic deemed overly relaxed—like the guys who showed up with sagging pants—and embraces a carefree, childlike silliness that resonates with the city’s character and its people.

Mocking sagging pants at ‘Chengdu Disney.’

Despite the influx of visitors to the Chengdu Disney area, authorities have not yet significantly intervened. Community notices urging respect for nearby residents and the presence of police officers to maintain order indicate a relatively hands-off approach. For now, it seems most people are simply enjoying the relaxed atmosphere.

Being Part of the Meme

An important aspect that contributes to the appeal of Chengdu Disney is its nature as an online meme, allowing people to actively participate in it.

Scenes from Chengdu Disney, images via Weibo.

China has a very strong meme culture. Although there are all kinds of memes, from visual to verbal, many Chinese memes incorporate wordplay. In part, this has to do with the nature of Chinese language, as it offers various opportunities for puns, homophones, and linguistic creativity thanks to its tones and characters.

The use of homophones on Chinese social media is as old as Chinese social media itself. One of the most famous examples is the phrase ‘cǎo ní mǎ’ (草泥马), which literally means ‘grass mud horse’, but is pronounced in the same way as the vulgar “f*ck your mother” (which is written with three different characters).

In the case of the Chengdu Disney trend, it combines a verbal meme—stemming from the ‘diss nǐ’ / Díshìní homophone—and a visual meme, where people gather to pose for videos/photos in the same location, repeating the same phrase.

Moreover, the trend bridges the gap between the online and offline worlds, as people come together at the Chengdu playground, forming a tangible community through digital culture.

The fact that this is happening at a residential exercise park for the elderly adds to the humor: it’s a Chengdu take on what “urban” truly means. These colorful exercise machines are a common sight in Chinese parks nationwide and are actually very mundane. Transforming something so normal into something extraordinary is part of the meme.

A 3D-printed model version of the exercise equipment featured in Nuomi’s music video.

Lastly, the incorporation of the Disney element adds a touch of whimsy to the trend. By introducing characters like Snow White and Mickey Mouse, the trend blends American influences (hip-hop, Disney) with local Chengdu culture, creating a captivating and absurd backdrop for a viral phenomenon.

For some people, the pace in which these trends develop is just too quick. On Weibo, one popular tourism blogger (@吴必虎) wrote: “The viral hotspots are truly unpredictable these days. We’re still seeing buzz around the spicy hot pot in Gansu’s Tianshui, meanwhile, a small seesaw originally meant for the elderly in a residential community suddenly turns into “Chengdu Disneyland,” catching the cultural and tourism authorities of Sichuan and even Shanghai Disneyland off guard. Netizens are truly powerful, even making it difficult for me, as a professional cultural tourism researcher, to keep up with them.”

By Manya Koetse, co-authored by Ruixin Zhang

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

In Hot Water: The Nongfu Spring Controversy Explained

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

-

China World2 months ago

China World2 months agoFrom Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)