China Health & Science

The “Last Downer”: China and the End of Down Syndrome

With screenings for Down syndrome becoming more advanced, there are less and less babies being born with Down in China every year. Unborn babies with Down syndrome are allowed to be aborted to up to nine months of pregnancy.

Published

10 years agoon

New screenings that can predict if an unborn baby has Down syndrome have sparked wide debate across the world – mostly because their results often lead to parents choosing for abortion. The ethical debate that is so alive in many countries seems practically non-existent in China, where Down syndrome is slowly disappearing from society. Unborn babies with Down syndrome are allowed to be aborted to up to the ninth month of pregnancy; 21% of Down-related abortions in China occur during or after the seventh month.

Last month was World Down Dyndrome Day (世界唐氏综合征日, March 21) and next month marks China’s National Disability Day (全国助残日, May 15) – both are occasions when Chinese media pay extra attention to Down syndrome, a disorder that is slowly disappearing from Chinese society.

On World Down Syndrome Day, Chinese state media broadcaster CCTV wrote on its Weibo account: “Currently, medical science does not have effective prevention and treatment methods for Down syndrome, but it can be detected early through prenatal screening. You might have seen this kind of face: mouth slightly open, a blank expression, eyes somewhat wide apart,.. break your prejudices and understand them!” This text is accompanied by different facts about Down syndrome pictured with a cartoon baby on CCTV’s account page (pictured below).

“I’m still nervously awaiting the results of the amniotic fluid test,” one netizen responds to the post: “I hope my baby is healthy and normal.”

On Chinese social media, many expecting mothers express their worries about screening results and the health of their unborn child. But the ethical debate that is so alive in many other countries about Down syndrome screening and abortion seems practically non-existent in China. One Weibo user comments: “In foreign countries, there are many mothers raising kids with Down, because their religion does not allow them to abort the baby.”

THE “LAST DOWNER”

“New medical techniques and the ethical questions that come with it have caused ample discussion on Down syndrome in many nations across the world.”

Down syndrome (DS) is a congenital disorder caused by a chromosome defect, that exists in all regions worldwide. Children with DS often have an intellectual disability and are also affected physically in their appearance and general health. Down syndrome has an incidence of 1 in 600–1000 live births, differing per country (UN; Wang et al 2013, 273). The disorder was named after John Langdon Down, the British physician who first classified this genetic disorder in 1862. In Chinese, it is known as 唐氏综合征 (Tángshì zònghézhēng) or as 先天愚型 (Xiāntiān yúxíng), the latter literally meaning ‘naturally stupid-type’.

With new techniques, it has become easier for doctors to safely detect whether or not a fetus has Down syndrome. In many countries, women can now choose for first-trimester prenatal screenings that can indicate the likelihood they are carrying a baby with Down syndrome. These tests can be followed up with diagnostic tests, either through amniocentesis (amniotic fluid test) or a DNA blood test, that can give a conclusive answer. If the unborn baby turns out to have DS, parents often have the option to abort it.

These new medical techniques and the ethical questions that come with them have caused ample discussions on Down syndrome in many nations across the world. Denmark introduced national guidelines for prenatal screening and diagnosis as early as 2004, which has led to an all-time low of Danish infants with Down syndrome – 95%-98% of pregnant women choose to abort a fetus with DS (Vice 2015). This means that Down could become something of the past; not just in Denmark, but also in other countries that have followed its example after 2004.

According to anti-abortion media, what is happening in Denmark is a “targeted form of genocide.” In the United States, the test has also become a focus of controversy, as it is intertwined with America’s general debate over abortion.

The Dutch TV-series “The Last Downer” (sic) explored the gradual disappearance of Down Syndrome. The show was co-hosted by two young adults who were born with DS themselves. Photo via NPO/NRC of TV Show “De Laatste Downer.”

In the Netherlands, a TV show revolving around ‘the end of Down syndrome’ was recently aired on national television. The series, that was titled ‘The Last Downer’, explored what society loses if Down syndrome disappears. It also talked about the ethical, social and psychological consequences of having a child with Down syndrome. ‘The Last Downer’ also triggered debate, as some critics deemed that it was too much in favor of the pro-life movement.

DOWN SYNDROME IN CHINA

“21% of abortions related to DS in China take place after the 28th week of pregnancy.”

In China, it is estimated that 1 out of 700 infants are affected with Down syndrome. Although this percentage is relatively low compared to other countries, it is an enormous figure nevertheless due to China’s huge population (Deng et al 2015, 311).

China’s Ministry of Health has promoted nationwide prenatal screenings for birth defects since 2003 (312). As pointed out in recent Chinese research, there has since been a sharp increase in the percentage of prenatal diagnosis and consequential birth termination (Deng et al 2015, 315).

The detection of Down syndrome through prenatal diagnosis in China went from nearly 13% in 2003 to over 69% in 2011 – with urban women having better access to early screenings and diagnosis than women living in the more rural areas of China. Around 95% of women terminate their pregnancy after learning the baby has DS, which is close to similarly high numbers in countries like Denmark or Hungary.

What is different in China, is that abortions can take place up to the ninth month of pregnancy.* In nearly 80% of the cases where the DS diagnosis led to abortion, this termination took place before 28 weeks. In the other cases, the pregnancy was terminated later than 28 weeks; meaning that 21% of abortions related to DS take place after the 28th week of pregnancy (ibid. 2015, 315).** In, for example, the Netherlands, abortion can take place up to 24 weeks of pregnancy, which is determined as the moment after which a fetus would be able to survive outside the uterus. Denmark allows for abortions to take place until the 12th week of pregnancy.

Chinese doctors encourage screening more strongly when pregnant women are older. According to current regulations in China, pregnant women aged 35 or above will be suggested to have an amniocentesis test directly, and, as research points out, “most Chinese women opt to abort fetuses with malformations” (Deng et al 2015, 316). Overall, the prevalence of prenatal diagnosis of DS and the number of related abortions is higher in urban areas than in China’s rural areas due to better medical facilities in cities. This also suggests that the majority of babies with DS are now born in the countryside, where parents do not always have access to the medical care they need.

ABORTION IS OKAY

“Bright-pink advertisements on ‘painless abortions’ depict smiling women, butterflies and flowers.”

On Weibo, many netizens share their experiences with prenatal screening. One pregnant woman says the test has cost her 191 RMB (±30 US$), another netizen responds: “In my hometown, these screenings are free of charge!” Another Weibo user shares her anxiousness: “I’ve been worrying about this Down screening all week,” she writes on April 21st. The following day, she replies to the comments with crying emoticons.

Although the screenings are a big issue on Chinese social media, the ethical question of the abortions is seemingly not. This might relate to the fact that abortion is not as contentious in China as it is in many other countries.

Pregnancy termination became quite common in China during the 20th century in relation to the one-child policy. By now, China has the highest abortion rate in the world. According to the National Health and Family Planning Commission, 13 million abortions are carried out in China every year. The actual number is probably much higher, as the official number does not include the abortion numbers from private clinics, nor the estimated 10 million induced abortions per year through medicine (Xinhua 2014), nor the numbers of sex-selective abortions– a practice that has officially been illegal since 2004.

The prevalence of abortions in China has led to a booming industry focused on abortion procedures. Bright-pink advertisements on ‘painless abortions’ depict smiling women, butterflies and flowers.

Some even promise that the abortion will be over within ‘a dreamlike three minutes’ (for more on this read: Glamorous & Painless – China’s Booming Abortion Industry). Although China has a painful past when it comes to forced abortions, the personal choice for abortion is not as controversial as it is in many countries where the Down syndrome detection debate is more alive.

“I’m drinking fresh rosedew after my abortion,” one netizen writes: “It’s good for my cold womb.”

THE HARDSHIPS OF DOWN CHILDREN IN CHINA

“Giving a child with Down syndrome up for adoption is very difficult, as China’s DS children are generally deemed ‘unadoptable’.”

Besides the fact that abortion is considered relatively uncontroversial in China, the high rate of abortions for DS-diagnosed babies might also relate to the fact that disabled children face many difficulties in China due to stigmatization and practical hurdles.

Raising a handicapped child is a heavy burden for many parents in China, who receive little government support and often do not have the means to make sure their child gets the medical care and education they need. This means that abandoning the child sometimes is the only solution for parents to make sure their child is taken into an institution (Yoxall 2008, 25).

Giving a child with Down syndrome up for adoption is very difficult, as China’s DS children are generally deemed ‘unadoptable‘. Until recently, it was legally not possible to adopt a child with Down within China. Since this has now changed, international organizations like the Bamboo Project help parents who want to adopt a child with Down syndrome from China.

SCREENINGS FOR DOWN: ANXIETY & CONFUSION

“If your baby has Down syndrome, you can’t keep it – you do understand this, don’t you?”

In China’s urban areas, first-trimester screenings for DS (唐氏筛查) through a blood test have become practically mandatory. Some clinics have 100% screening guidelines for all of their patients, but do ask parents to sign for consent first; other hospitals simply proceed to include the test with general pregnancy check-ups without any permission.

Screening procedures differ per hospital and can be confusing for expecting mothers: “Today my doctor told me that because I am already 35, I should do an amniocentesis test,” one netizen writes on Weibo: “but the blood test in my first trimester indicated I had low risk of having a baby with Down. I’m very confused if I should do it or not.”

China’s screening procedures and prevalent attitudes on how to deal with a baby that possibly has DS can be shocking to some. A 31-year-old Dutch mum named Anna (alias), who lives in Shanghai, recently shared her experiences on Facebook. Anna, pregnant with her second baby, writes:

“I was unable to come on Facebook for some time due to problems with my VPN. During this period, I’ve come across something that I loathe even more than China’s internet censorship. “They’ve tried calling you but you didn’t pick up,” the Chinese nurse tells me while looking up from a form, as she points me to an examination room. I walk in, and ask the doctor what’s going on – I vaguely remember a ‘standard’ blood test (..) – “‘You have an increased risk for a child with a mental disability,’ the doctor straightforwardly tells me. ‘Excuse me?’ – I ask her to repeat her sentence. ‘The child might be retarded,’ she tells me.”

Anna writes: “In the Netherlands, the availability of prenatal tests for Down syndrome has caused quite some controversy earlier this year. It is not allowed for doctors to proactively encourage women to do this test unless there’s an increased risk for them to have a child with an intellectual disability – because they are above the age of 40, for example. But this is not the case in China, where every pregnant woman, no matter her age, is tested for heightened risk through blood screening. I ask the doctor what the test results are, since I’m only 31. ‘Well, that’s not like being 21 anymore, now it is?’ she snarls at me.”

Anna explains that the results of her blood test showed there was a 1-in-200 chance her baby had Down syndrome. After informing Anna about this, the doctor says: “You can choose if you now want an amniocentesis or a DNA test. The first is more expensive and needs to be done in a private clinic, here’s an information leaflet, just think about it.”

She chooses to do the DNA test, which is safer for mothers and their unborn babies than the amniocentesis. She says: “I was initially just shocked to hear there was an increased risk for me to have a child with a disorder, but it also bothered me that the initial screening was done without my consent. I ask the doctor what happens if my baby turns out to have Down syndrome. ‘Then you can’t keep it,’ she gives me a piercing look: ‘You do understand this, don’t you?’”

Anna writes: “She advised me to timely book a possible abortion, but that the procedure would be possible until 32 (!) weeks.” Anna receives the DNA test results a week later through text message, and her baby shows no signs of abnormalities. Despite her relief, she feels uncomfortable about the intrusive way in which her prenatal screening and its possible outcome was handled.

Another foreigner living in Beijing told What’s on Weibo they also were tested for Down syndrome risks in the first trimester of pregnancy at Beijing United hospital without being asked for permission first. Although they were surprised to get the results, they did not react strongly to it as the test turned out to be very low risk.

Although the ethical debate on this issue is generally lacking from mainstream media, one story did make headlines last year when a woman from Hubei was determined to end her pregnancy at 16 weeks because of the Down syndrome screening. The initial blood screenings showed an increased risk of DS, and the woman arranged an abortion – in spite of the doctors convincing her that she should wait for the actual diagnoses screening first. This story also shows how intertwined prenatal screenings and abortion have become.

DS IN CHINA: TABOOS AND SOCIAL STIGMA

“I think my sister’s baby has Down syndrome, but I am too afraid to ask her.”

Chinese netizens share their experience with Down syndrome on various online message boards. One netizen tells how it is growing up with a brother with Down syndrome. “My brother was born prematurely and was in weak health. The doctor told my parents to just give up on him. But my father refused to give up, because it was a boy, and he thinks boys are worth more than girls. So my brother lived.” The netizen tells how his parents were told by doctors that their child was simply “hopeless”, and that his brother was always teased in school.

On message board Douban, multiple netizens share how doctors encourage couples to have an abortion if their unborn baby is diagnosed with DS. The discussion of Down on Chinese social media shows that DS is heavily stigmatized and that it is sometimes also considered a taboo. Some netizens tell about former classmates with Down who were constantly bullied, and one netizen writes: “I think my sister’s baby has Down syndrome, but I am too afraid to ask her.”

Now that rapidly advancing medical techniques have decreased the prevalence of DS in China, chances are that the less common the disorder is, the more stigmatized it will become. It is also probable that over the next one or two decades, if rural areas get better access to medical care, Down syndrome will altogether disappear from China.

For China’s upcoming ‘day for the handicapped’, multiple organizations try to raise more public awareness for Down syndrome. This year, the day will specifically focus on handicapped orphans. For this occasion Chinese media recently wrote about an orphanage in Tianjin, where one-third of all children are Down syndrome babies who were left behind by their parents.

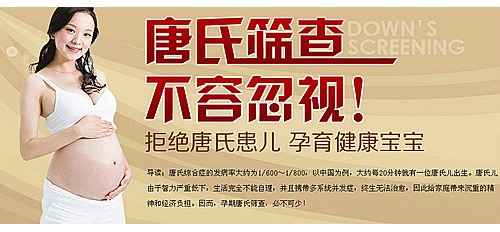

Although the article describes children with DS as little “happy angels”, one Chinese birth clinic seems to think otherwise. In their ad (see image), their message is loud and clear: “Reject children with Down syndrome! Give birth to a healthy baby!” Angels or not, modern-day China seems to have no place for Down syndrome children.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

[rp4wp]

References

Wang, S.-S., Wang, C., Qiao, F.-Y., Lv, J.-J. & Feng, L. 2013. “Polymorphisms in genes RFC-1/CBS as maternal risk factors for Down syndrome in China.” Arch Gyneocol Obstet 288: 273-277.

Deng, C., Yi, L., Mu, Y., Zhu, J., Qin, Y., Fan, X., Li, Q. & Dai, L. 2015. “Recent trends in the birth prevalence of Down syndrome in China: impact of prenatal diagnosis and subsequent terminations.” Prenatal Diagnosis, 35(4), 311–318.

Yoxal, James W. 2008. China’s Social Policy: Meeting the Needs of Orphaned and Disabled Children. Master Thesis, Union Institute & University.

NB: other references are linked to in-text.

* As written by Deng et al (2015): “Following a systemic and standardized diagnostic process, pregnancy affected by severe anomalies such as DS is allowed to be terminated at any gestational age following informed consent” (312).

** According to 2003-2011 surveillance data, study by Deng et al uses data from the Chinese Birth Defects Monitoring Network.

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chapter Dive

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

Han Futao’s explosive report on fake patients and systemic abuse has triggered a heated online debate over hospital malpractices, the fragility of the welfare system, and the vital role of investigative reporting.

Published

4 days agoon

February 15, 2026By

Ruixin Zhang

In early February, as China settled into the quiet anticipation of the Chinese New Year, one of the country’s leading investigative journalists, Han Futao (韩福涛), dropped a bombshell report that sent shockwaves of anger across the country.

Han Futao is known for breaking massive scandals. In 2024, he exposed how tank trucks that delivered chemical products also transported cooking oil, without being cleaned. That food safety scandal sparked waves of outrage and prompted a high-level official investigation, leading to criminal charges for those involved.

In his latest explosive report, published by Beijing News (新京报), Han has turned his lens to malpractice in China’s hospital sector. His investigation led him to Xiangyang, in Hubei province, a city with more than twenty psychiatric hospitals, cropping up on every corner “like beef noodle shops” over recent years.

Recruiting Patients

Han found that multiple private psychiatric hospitals lure people in under the guise of free care, promising treatment for little or no cost, along with medication and daily expenses. Some even dispatched staff to rural villages to recruit “patients.”

Troubled by the unusual marketing procedures of these psychiatric hospitals, Han went undercover at several facilities as a caregiver, and sometimes posing as a patient’s family member, only to expose a disturbing reality.

Except for a handful of genuine patients, these hospitals were filled with healthy people who actually received no treatment. Many were elderly citizens swayed by the promise of “free care,” checking in with the hope of finding a free retirement home.

When Han, posing as a patient’s family member, spoke to a hospital manager at Xiangyang Yangyiguang Psychiatric Hospital (襄阳阳一光精神病医院), the director enthusiastically pitched their “free hospitalization” by saying medical fees were completely waived and promising the potential patient a great stay: “Lots of patients stay here for years and don’t even go home for Chinese New Year!”

Meanwhile, the hospitals’ own staff, including caregivers, nurses, and security guards, were also officially registered as patients, complete with admission and hospitalization procedures.

The motive was simple: insurance fraud (骗保 piànbǎo). In China, even after state medical insurance covers part of psychiatric care costs, patients are typically still responsible for a co-pay. These hospitals, both in Xiangyang and in the city of Yichang, exploited the financial vulnerability of those unwilling or unable to pay, using the lure of free accommodation to attract the misinformed. Once admitted, the hospitals used their identities to fabricate medical records and bill the state for non-existent treatments.

According to internal billing records, medication accounted for only a small fraction of patients’ costs. The bulk of the charges came from psychotherapy and behavioral correction therapy, which often leave little material trace and, in these cases, were never actually provided. Many of these hospitals even lacked basic medical equipment and qualified personnel.

Staff were essentially manufacturing invoices, generating around 4,000 yuan (US$580) in fraudulent charges per patient each month, with most funds diverted from the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA).

With each patient yielding thousands of yuan, profitability became a numbers game: the more bodies in beds, the higher the revenue. This perverse incentive gave rise to a specialized workforce of marketers who recruited ordinary people from rural areas, developing sales pitches and establishing referral-based kickback chains, offering bonuses of 400 ($58) to 1,000 yuan ($145) for every new “patient” successfully brought in.

To stay under the radar, hospitals periodically discharged patients on paper to avoid scrutiny from insurance auditors, only to readmit them immediately, or never actually let them leave at all. One story involved a patient who was discharged seven times, each time being readmitted on the same day he was “discharged.”

Day after day, the national medical insurance fund, built on the collective contributions and trust of the entire population, was drained through these calculated deceptions.

From Patients to Prisoners

Han uncovered more. Even more harrowing than the scale of the medical insurance fraud was the condition of those trapped inside. To maximize profit margins, these hospitals slashed costs to the bone. Living conditions were terrible: wards overcrowded, beds crammed side-by-side, and daily activities and food substandard at best.

The hospitals treated their patients more like profit-generating assets than human beings. Patients were subjected to a strict regime: they were forced to follow rigid schedules, restricted to designated zones, and faced physical violence if they did not comply.

During Han’s undercover research, he witnessed the horrific sight of patients being tied to a bed for not following orders, with some patients allegedly being restrained for up to three days and three nights.

Photo by Han Futao, in Beijing News, showing a hall filled with beds at the Yichang Yiling Kangning Psychiatric Hospital, where more than 160 people were housed in just one ward. The lower photo, also by Han Futao, shows elderly “patients” kept in their wheelchairs all day at Xiangyang Hong’an Psychiatric Hospital.

Some patients, despite technically being the ones receiving care, were forced to perform manual labor for the staff. They scrubbed pots, cleaned wards, mopped latrines, and moved supplies. Others even had to take on nursing tasks for fellow patients, such as feeding, bathing, and changing clothes, all in exchange for a few cents to buy a cigarette. Their personal freedom and quality of life were virtually non-existent.

Escape was also difficult. The hospitals had no intention of releasing their cash cows. Rarely was a patient discharged on the scheduled date. To ensure long-term residency, many hospitals confiscated patients’ phones and cut off contact with their families.

Some individuals spent nearly ten years in these prison-like conditions; some even died there. Meanwhile, those truly suffering from mental illness received no real treatment, often seeing their condition worsen or developing deep-seated trauma toward psychiatric care.

Fragile Public Trust in Welfare-Related Institutions

In China, there is a common belief that if you spot one cockroach in the room, there are already a hundred more hiding. As the story has gone viral over the past two weeks, netizens pointed out that Xiangyang and Yichang were likely not the only cities using such predatory tactics to cannibalize the national treasury. Han’s investigation struck a deeper nerve, and public anxiety over the security of social insurance once again bubbled to the surface.

China’s national health insurance is a cornerstone of the broader social insurance system and a vital part of life for nearly every citizen. It is generally divided into two categories: Employee Medical Insurance and Resident Medical Insurance. Employers are legally, at least in theory, required to contribute to the employee scheme, typically 6% to 9% of a worker’s salary. Non-employees, such as farmers, students, and freelancers, usually pay for Resident Insurance out of pocket, currently costing around 400 yuan ($58) annually. Under the employee scheme, inpatient reimbursement rates are roughly 80% to 85%; after approximately 25 years of contributions, members enjoy lifelong coverage without further payments. The Resident Insurance, however, offers significantly lower protection.

This system was designed as a fundamental safety net to alleviate the fear of falling into poverty due to illness or being left destitute in old age. For young Chinese job seekers, whether a company pays into social security used to be a non-negotiable criterion. However, as scandals shaking the foundation of this system have become more frequent, the mindset of the youth is shifting: Is it even worth paying into anymore?

Recent years have seen a steady stream of corruption scandals involving the embezzlement of social security funds.

Despite the authorities’ firm stance and high-profile punishments, 2025 was still marked by reports of officials — including the insurance bureau’s finance head — misappropriating funds to play the stock market. A June 2025 report even alleged that 40.6 billion yuan (US$5.8 billion) in national pension funds had been misappropriated or embezzled by local governments.

In one surreal case from Shanxi, a CDC employee’s records were doctored 14 times to create an absurd history of “starting work at age 1 and retiring at 22,” allowing them to pocket 690,000 yuan ($100,000) in pension while still drawing a salary at a new job.

These stories exposing large-scale abuse of the medical insurance system, combined with the extension of the minimum contribution period for retirement from 15 to 20 years amid a slowing job market and a gradually rising retirement age, are leading netizens to question the necessity of paying into the system. This is reflected in comments such as:

-“First it was 20 years, then 25, then 30. They move the goalposts whenever they want, but the benefits never improve.”

-“I won’t buy anything beyond the bare minimum resident insurance; who knows if there will even be a payout in the future?”

-“With a deficit this large, whether we’ll ever see that money is a huge question mark.”

-“I’m not even sure I’ll live to see 65 anyway.”

Echoes of the Cuckoo’s Nest

In response to Han’s latest exposure, local authorities immediately launched investigations, and state-run media outlets issued sharp criticism. By now, fourteen hospital executives have been criminally detained on suspicion of fraud.

Although the official report, published on the night of February 13, acknowledged that there was widespread medical fraud, with patients remaining hospitalized after recovery or empty beds being registered without any patients there, it said no evidence was found that people without mental disorders were admitted, which was one major finding of Han’s undercover operation.

This led to new questions, because how could fraud, abuse, fake discharges, and official corruption be acknowledged while denying the central allegation: that healthy people were being locked up? And how could people prove they were not mentally ill, while being a patient inside a psychiatric hospital?

Political & social commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) wrote on Weibo that, while he applauded Han and his team for exposing the mismanagement at psychiatric hospitals in Hubei, he also saw the report’s conclusions about the patients as a reminder that journalists should exercise caution when making accusations. Some sarcastic commenters suggested that perhaps Han had not sacrificed enough and should have admitted himself as a patient instead.

And so, in a way, the debate has now slowly also shifted – from the initial shock over Han’s report, to the anger and distrust surrounding state institutions and social security abuse, to the role of investigative journalism in China today. “He’s a hero,” some commenters said about Han.

In the end, the entire story is so absurd that some commentators have drawn parallels to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (飞越疯人院), where Randle P. McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) fakes insanity to serve his sentence in a mental hospital instead of a prison work farm, only to find out that the endless chain of control and abuse at the psych ward is much more brutal than a prison cell.

The question inescapably becomes who the sane ones actually are.

Meanwhile, the scandal shows that public anxiety about the future and distrust of state institutions tend to rise quickly and deepen slowly with each new controversy. As trust in the national welfare system appears fragile, one sentiment persists: that there is far more to uncover, and that there are far too few Han Futaos to do it.

By Ruixin Zhang

With additional reporting by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Animals

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

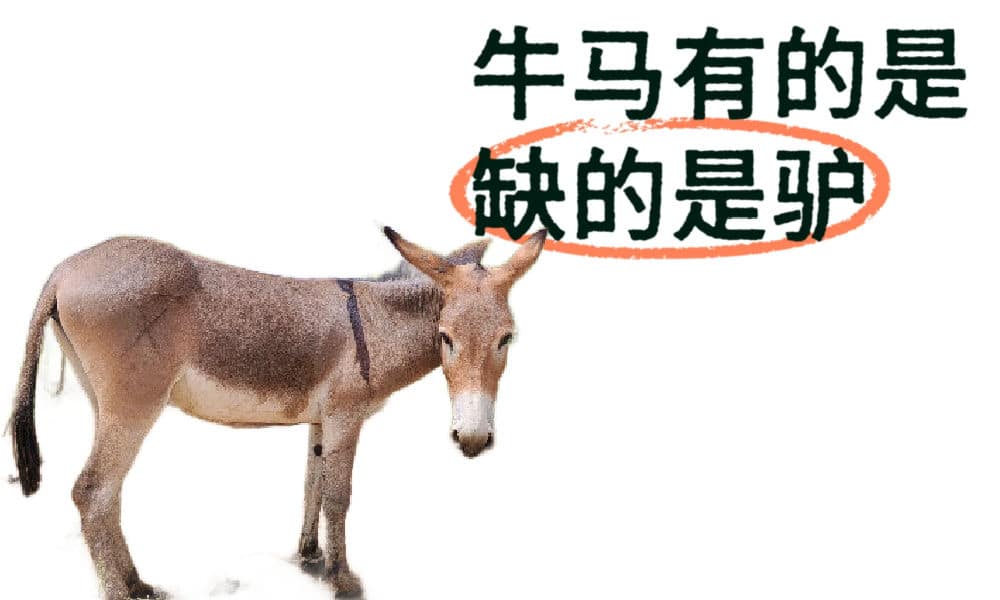

“We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

Published

5 months agoon

October 5, 2025

China is facing a serious donkey shortage. China’s donkey population is far below market demand, and the prices of donkey-related products continue to rise.

Recently, this issue went trending on Weibo under hashtags such as “China Currently Faces a Donkey Crisis” (#我国正面临缺驴危机#).

The Donkey Branch of China’s Livestock Association (中国畜牧业协会驴业分会) addressed this issue in Chinese media earlier last week, telling China News Weekly (中国新闻周刊): “We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

China’s donkey population has plummeted by nearly 90% over the past decades, from 11.2 million in 1990 to just 1.46 million in 2023.

The massive drop is related to the modernization of China’s agricultural industry, in which the traditional role of donkeys as farming helpers — “tractors” — has diminished. As agricultural machines took over, donkeys lost their role in Chinese villages and were “laid off.”

Donkeys also reproduce slowly, and breeding them is less profitable than pigs or sheep, partly due to their small body size.

Since 2008, Africa has surpassed Asia as the world’s largest donkey-producing region. Over the years, China has increasingly relied on imports to meet its demand for donkey products, with only about 20–30% of the donkey meat on the market coming from domestic sources.

China’s demand for donkeys mostly consists of meat and hides. As for the meat — donkey meat is both popular and culturally relevant in China, especially in northern provinces, where you’ll find many donkey meat dishes, from burgers to soups to donkey meat hotpot (驴肉火锅).

However, the main driver of donkey demand is the need for hides used to produce Ejiao (阿胶) — a traditional Chinese medicine made by stewing and concentrating donkey skin. Demand for Ejiao has surged in recent years, fueling a booming industry.

China’s dwindling donkey population has contributed to widespread overhunting and illegal killings across Africa. In response, the African Union imposed a 15-year ban on donkey skin exports in February 2023 to protect the continent’s remaining donkey population.

As a result of China’s ongoing “donkey crisis,” you’ll see increased prices for donkey hides and Ejiao products, and oh, those “donkey meat burgers” you order in China might actually be horse meat nowadays. Many vendors have switched — some secretly so (although that is officially illegal).

Efforts are underway to reverse the trend, including breeding incentives in Gansu and large-scale farms in Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang.

China is also cooperating with Pakistan, one of the world’s top donkey-producing nations, and will invest $37 million in donkey breeding.

However, experts say the shortage is unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

The quote that was featured by China News Weekly — “We have cows and horses, but no donkeys” (“牛马有的是,就缺驴”) — has sparked viral discussion online, not just because of the actual crisis but also due to some wordplay in Chinese, with “cows and horses” (“牛马”) often referring to hardworking, obedient workers, while “donkey” (“驴”) is used to describe more stubborn and less willing-to-comply individuals.

Not only is this quote making the shortage a metaphor for modern workplace dynamics in China, it also reflects on the state media editor who dared to feature this as the main header for the article. One Weibo user wrote: “It’s easy to be a cow or a horse. But being a donkey takes courage.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

Colette

July 18, 2016 at 1:02 am

In the UK termination for DS is also permitted until 9 months………Lord Shinkwin is trying to change this.

jack

October 27, 2016 at 3:40 am

The truth is the chinese and the Japanese are a mongoloid race they were created from the daughters of a man called Lot the nephew of abraham in the bible read the story of Sodom and gomorrah this will tell of Lots two daughters and there plan…the modern day chinese are the moabites and the Japanese are the modern day ammonites,incest causes down syndrome or retardation these two nations are the product of incest…BASTARD babies…truth is hard to accept

Anonymous

December 27, 2016 at 6:11 am

Please go back to /pol/.