China Tech

ChatGPT in China: Online Discussions, Concerns, and China’s ChatGPT-Style Bots

Why was a ChatGPT-like platform not first launched in China? As ChatGPT is all the talk, so is the discussion about China catching up.

Published

3 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT

As OpenAI’s AI chatbot ChatGPT has become one of the fastest-growing platforms ever, it is making headlines every day these days. It is also a hot topic on Chinese social media, where many wonder why ChatGPT was not developed in China and what the future holds for similar platforms in the mainland.

As ChatGPT has been making headlines internationally, the AI software has also become a popular topic on Chinese social media.

ChatGPT is software that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to write pieces of text. It was launched by OpenAI, an American AI lab founded in 2015, and within two months after its Nov. 30 2022 release, ChatGPT reached 100 million active users.

As explained by ChatGPT itself, it has been designed to generate human-like responses to a wide range of questions and topics, based on the text data it was trained on.

ChatGPT is built using the GPT-3 architecture, which stands for ‘Generative Pretrained Transformer 3.’ This architecture allows ChatGPT to generate coherent and contextually relevant responses to a wide range of questions and prompts in many different languages, making it a powerful tool for various applications, including customer service or content creation.

Even if you have not yet visited the ChatGPT chatbot site, you might have come across the technology underlying ChatGPT, which is already used in chatbots for customer service purposes by companies such as Meta, Canva, and Shopify.

ChatGPT on Chinese Social Media

Ever since China’s Spring Festival, ChatGPT has been a hot topic on Chinese social media, with many people interacting with the chatbot and sharing AI-generated texts online, varying from cute poems about Chinese cities to helpful breakfast suggestions.

On Weibo, various hashtags related to ChatGPT made it to the top trending lists recently. Some online discussions relate to what extent applications such as ChatGPT might make certain professions obsolete, or to how to address the problem of students using AI chatbots to make their homework or write essays.

There are also discussions about the privacy- and copyright problems related to the technology. The American linguist and renowned intellectual Noam Chomsky recently said that “ChatGPT basically is high-tech plagiarism,” a topic that also received a lot of attention on Weibo, where a related hashtag received 56 million views (#语言学家称ChatGPT本质是剽窃#).

The hashtag “Will ChatGPT Replace Teachers?” (#教师会被ChatGPT取代吗#) went trending on Weibo on Feb. 11, 2023. Previously, other related hashtags also questioned if programmers might lose their job because of the application.

CCTV also published about ChatGPT on Feb. 11, writing about “Ten Professions That Could be Replaced by ChatGPT” (#可能被ChatGPT取代的10大职业#), suggesting that jobs from various industries, including customer service, programming, media, education, market research, finance, etc., involve daily tasks that could also be executed by AI chatbots.

The hashtag, which received over 120 million views on Weibo, sparked conversations. Although many commenters said that some jobs, including teaching, would never be able to be replaced by artificial intelligence, some also predicted that these kinds of technologies could definitely make some jobs obsolete.

“We all thought that AI would first replace those working in physical labor instead of taking over mental capacity tasks,” one commenter wrote, with another replying: “Construction workers will still have a steady job.”

“Relax, such a chatbot can only do simple tasks, but humans have a different way of thinking from machines,” another person wrote: “Professions such as teachers or programmers need innovative ways of thinking that AI doesn’t have.”

Besides these topics, there are also Chinese social media discussions about why China – as a global AI leader – was not the first to launch such a product. Then there are those discussions about the specific difficulties surrounding the development of such a chatbot in the Chinese online environment.

Why is China not the First to Launch a ChatGPT-like Product?

The question “Why was ChatGPT not made in China?” is one that is frequently asked on Chinese social media these days, and various experts and bloggers come up with different answers.

◼︎ Chinese tech companies focus on fast applications instead of lengthy research and development

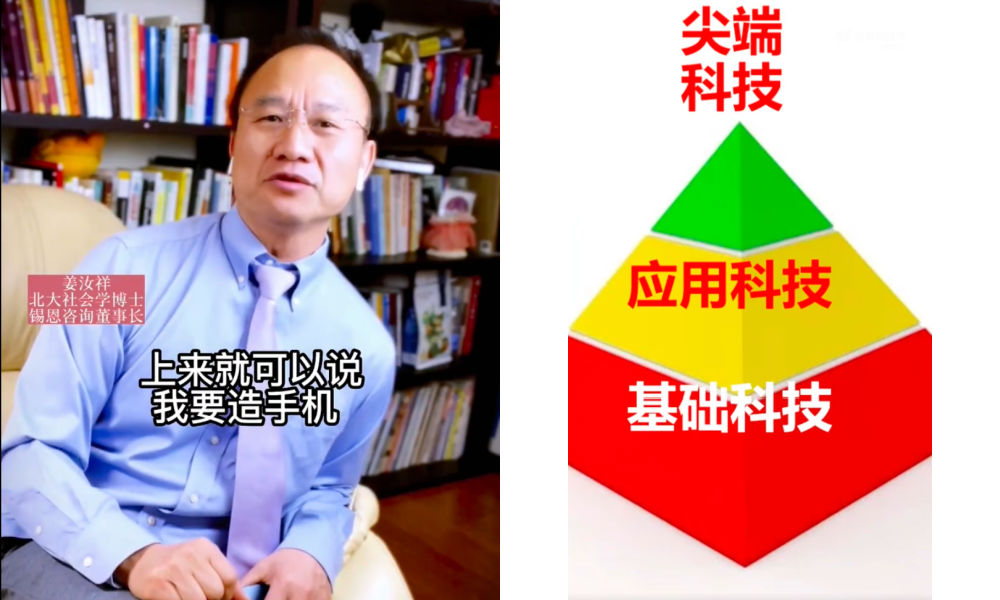

In a recent video, the Peking University Sociology Professor Jiang Ruxiang (姜汝祥) tried to answer this question: “Why is this kind of breakthrough, advanced technology not made in China?”

According to Jiang, the reason that ChatGPT is not ‘made in China’ has to do with the whole structure of science and technology in the mainland and the primary area of focus of China’s major tech startups.

Jiang shows a pyramid which, at the basic level, has ‘the foundation of science and technology’; the middle level is ‘applied science and technology,’ and the top layer is the ‘most advanced science and technology.’

Jiang argues that Chinese tech companies are most active at the middle level. They are primarily interested in fast application of science and technology as this gives them the opportunity to become profitable within a relatively short time.

Jiang suggests that it takes most advanced technology companies years of investing before ever becoming profitable. As an example, he mentions the big chipmaker ASML, as it also took the Dutch company many years of heavily investing in research and development before finally making money.

At the same time, some Chinese tech companies, such as Xiaomi, managed to skyrocket their income within a relatively short time after starting their business. The research (first layer) and advanced tech (top layer) that is needed in order for these Chinese companies to launch their platforms and products do not necessarily come from China; they can be imported, adjusted, and optimized.

According to Jiang, Chinese companies should do more to focus on the basic and top level of the science and technology pyramid. By investing in advanced, specific technology areas and deep research, China’s science and tech development would have more long-term vision, knowledge intensity, and strength. Jiang says that the Dutch company Philips, for example, invested in the chipmaker business for years without making money. He also adds that ChatGPT development was made possible through the investments of, among others, Elon Musk and Microsoft.

◼︎ Language Model Training is more difficult in the Chinese language

Other experts claim that making a Chinese ChatGPT is more difficult due to the nature of the Chinese language. The less complex a language is, the easier it is for AI models to learn the rules.

Ding Wensuan (丁文璿), Professor of Artificial Intelligence and Business Analytics at Emlyon Business School, recently told Phoenix News reporters that Chinese AI tech programs are already very strong, but that language model training is somewhat harder due to the rich and complex nature of Chinese language.

ChatGPT does understand and generate text in many different languages, including Chinese, although some Chinese users suggest it indeed fails to capture nuances, such as when telling jokes in Chinese.

User asks ChatGPT in Chinese to tell a joke, and the app generates two corny jokes that do not seem to translate well about why a mummy doesn’t wear clothes (should be “because it’s all wrapped up” but translated is more like “stripped naked”) and about why birds don’t sing ‘Happy Birthday’ (should be because they already have their own melody, but this says because they were taught to ‘tweet tweet’).

◼︎ Censorship and (politically) sensitive words

Many bloggers and commenters think that the development of ChatGPT-like platforms is more difficult in China due to existing (political) sensitivities and the Chinese online environment, which is closely monitored and subjected to censorship.

When it comes to history, (geo)politics, current events, etc., ChatGPT not only generates certain answers that would otherwise be censored on the Chinese internet, but it also is accused of holding certain biases or double standards in how it handles requests.

“Considering the original principle of ChatGPT, I think it’s useless to compete with products such as ChatGPT in a place that has sensitive words everywhere,” one commenter writes, and others also echoed this view: “It is impossible for a Chinese version of ChatGPT to come out, too many words are sensitive.”

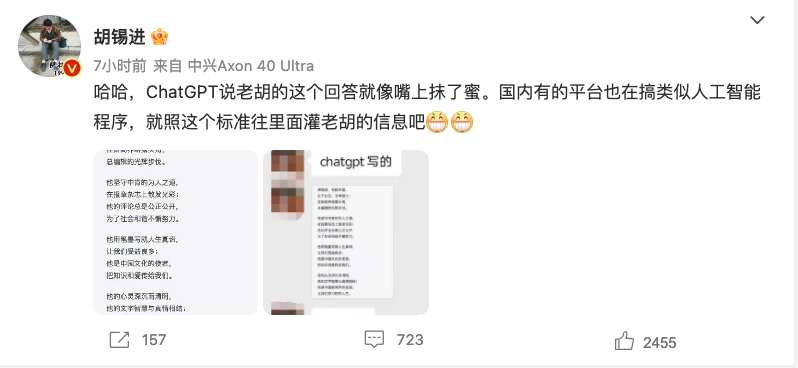

The well-known Chinese political commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) was happy to learn about some supposed positive bias on the platform: when one Chinese ChatGPT user asked the chatbox to write a text about him, it turned out to praise Hu, who is also known as outspoken and controversial.

An English poem about the former Global Times editor-in-chief generated by ChatGPT also contained the following:

“He’s a voice for China’s vision,

In a world that’s often torn,

With a mission to inform and guide,

And to keep his readers warm.

Through his words and his leadership,

Hu Xijin has made a name,

And his impact on the world,

Is one that will surely remain.”

Hu Xijin jokingly wrote: “Some domestic platforms are also working on similar artificial intelligence programs, so let’s hope they’ll all stick to this standard when it’s about me.”

China’s ChatGPT-Style Bots

As reported by Reuters, OpenAI or ChatGPT itself is not blocked by Chinese authorities, but OpenAI does not allow users in mainland China, Hong Kong, Iran, Russia, and parts of Africa to sign up.

Nevertheless, people find ways to register. Until recently, there were many shops on the e-commerce platform Taobao selling Chat GPT accounts. On Feb. 9, 2023, various accounts reported that the ChatGPT register services were censored on Taobao, and that affiliated services were also no longer available on WeChat (#淘宝已屏蔽ChatGPT关键词#).

Onlnie services to register for ChatGPT

Some commenters predict that there are no chances of survival for ChatGPT in China.

At the same time, while ChatGPT is receiving so much attention, Chinese tech giants announced their plans on developing similar AI platforms this week.

Baidu announced it plans to launch an AI chatbot called ErnieBot following testing in March (#百度类chatgpt产品名为erniebot#).

Tencent also announced their chatbot-related research is also “advancing” (#腾讯正有序推进ChatGPT方向的研究#).

Sources at Alibaba also said the company is already developing ChatGPT-like chatbots which are already being tested (#阿里类chatgpt产品正在内测#).

Chinese e-commerce company JD.com also said it would launch a similar product titled ChatJD (#京东正式推出产业版chatgpt#).

Chinese media outlet Caijing published an article about ChatGPT on Feb. 12, 2023, titled “Is the Chinese Version of ChatGPT Coming Soon?” (中国版ChatGPT快来了吗), in which it suggested that although China currently does not have an application that is comparable to ChatGPT yet, it will not take long for Chinese tech companies to catch up with OpenAI since China already has all the ingredients, including vast amounts of data, to create such a platform.

The article also argues that China should learn from ChatGPT’s success and to use its weaknesses as an advantage for its own chatbots.

“We can still catch up,” some commenters write. Although others agree, they also think that China’s online environment needs to be further liberalized in order for such AI platforms to flourish.

One blogger indicates that these kind of AI language models are already difficult enough to develop, let alone if they also have to avoid sensitive words or take certain censorship policies into account: “Of course we should not let AI talk nonsense, but it should be able to talk relatively neutral and objectively. In the end, the most important thing is whether or not they have the courage and insight to let go of the control of written language.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Part of featured image [screen] by Jonathan Kemper on Unsplash

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chapter Dive

How the “Nexperia Incident” Became a Mirror of China–Europe Tensions

From the Dutch invoking a Cold War–era law to Chinese narratives about Europe, this is what gives the Sino-Dutch “Nexperia incident” its extra weight.

Published

4 months agoon

October 14, 2025

🔥 This is premium content and also appeared in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

On the evening of October 12, while the Netherlands vs. Finland World Cup qualifier became a hot topic on Weibo (#荷兰4比0芬兰#), something else entirely made headlines — not about goals, but about chips.

Chinese company Wingtech Technology (闻泰科技) issued a statement saying that the Dutch government, citing national security concerns, had imposed global operational restrictions on Nexperia (安世半导体), a Dutch semiconductor company based in Nijmegen that has been wholly owned by the Chinese Wingtech conglomerate since 2019.

The Dutch government reportedly ordered a one-year freeze on strategic and governance changes across Nexperia on September 30, but the news only went trending on Chinese social media after Wingtech revealed the suspension (the topic became no 1 on Toutiao on Sunday).

Wingtech said that Nexperia’s Chinese CEO, Zhang Xuezheng (张学政), was also suspended, and that an independent, non-Chinese director was appointed who can legally represent the company.

That was ordered by a Dutch court following internal upheaval — Nexperia’s Dutch and German executives, including Legal Chief Ruben Lichtenberg, CFO Stefan Tilger, and COO Achim Kempe, filed a petition with the Dutch Enterprise Chamber requesting emergency measures to suspend Zhang and place the company’s shares under temporary court management. The court agreed (also see the Pekingnology newsletter by Zichen Wang, who was among the first to report on this issue).

The next day, on October 13, Dutch newspapers reported on the freeze, describing it as a rare move. NRC called it “an emergency measure intended to prevent chip-related intellectual property from leaving the country,” adding that, according to insiders, “there were indications that Nexperia was planning to transfer chip know-how to China.”

The Dutch government later clarified that the so-called Goods Availability Act (Wet Beschikbaarheid Goederen) was applied “following recent and acute signals of serious governance shortcomings and actions within Nexperia,” to protect Dutch and European economic security and safeguard crucial technological knowledge.

That specific law dates back to the Cold War era of 1952 and, according to Pim Jansen, professor of economic administrative law at Erasmus University Rotterdam, has never been invoked before. (Due to the unique situation, Jansen almost wanted to dub it the “Nexperia law.”)

🇳🇱 Nexperia (安世半导体) is a spin-off from chipmaker NXP, which in turn originated from Royal Philips. The company produces basic semiconductors that are used everywhere, from phones to cars. Since becoming independent in 2017, its headquarters in Nijmegen has expanded from about 150 to nearly 500 employees. Across its production sites in Germany, the UK, and Asia, Nexperia employs more than 10,000 people.

🇨🇳 Wingtech Technology (闻泰科技) is a major Chinese tech conglomerate listed on the A-share market and based in Jiaxing, combining two core businesses: semiconductors and electronics manufacturing. The company started in 2005 as a smartphone design and assembly firm (ODM) serving brands such as Xiaomi, Samsung, and Lenovo, and has since become one of the world’s largest mobile device manufacturers.

The recent developments are a big blow to Wingtech, as it basically means won’t be able to control day-to-day decisions at its most valuable subsidiary.

According to Wingtech, the suspension is politically motivated rather than fact-based and constitutes a serious violation of the market economy principles, fair competition, and international trade rules that the EU itself advocates.

The Wider Tech War Context

The Nexperia news is not an isolated case – it comes at a time when many things are happening at once.

🧩 On October 1, Dutch media reported that, due to tightening export rules announced by the United States, no American parts or software can be sold to Nexperia without a US license anymore because Nexperia’s Chinese parent company, Wingtech, is already on the American “Entity List,” and all of the company’s subsidiaries now also fall under the extended US export restrictions that took effect on September 29.

🧩 According to a Dutch media report on October 2, Nexperia said it strongly disagreed with the new export restrictions and was working on measures to limit their impact on its operations.

🧩 Barely two weeks prior, on September 18, China banned its tech companies from buying Nvidia AI chips from the American Nvidia, citing antitrust and national security reasons.

🧩 As of October, China also added several prominent Western companies to its Unreliable Entity List, including the Canadian-based research firm TechInsights.

🧩 And, as if that all wasn’t enough, China dramatically expanded its rare earth export controls on Thursday, expected to have a direct impact on the global semiconductor supply chain, while President Trump announced 100% tariffs on all Chinese imports and new export controls on “any and all critical software.”

👉 Regardless of how directly all these events are connected to what has happened in the Netherlands, one thing is clear: the global tech war is intensifying, with control over the semiconductor ecosystem now a top strategic priority.

And whatever the exact reasons or details behind the freeze of Nexperia’s strategic operations, on Chinese social media the move is being framed within a broader narrative — that of Western containment aimed at curbing China’s rapid rise as a global technological power.

Chinese Social Media Responses

On Chinese social media, commentators are denouncing the Netherlands.

One finance-focused Weibo blogger (@董指导挤出俩酒窝) wrote:

💬✍️ “By 2024, Nexperia contributed 14.7 billion RMB (2 billion U.S. dollars) in revenue and nearly 40% gross profit margin [to the Dutch economy]. According to Wingtech’s data, it also paid 130 million euros in corporate income tax to the Netherlands (..) This should have been a textbook case of mutual success – Chinese capital brought markets and vitality; the Netherlands benefited from taxes and employment; technology continued to grow in value within the global supply chain. Yet the Netherlands, showing its “pirate spirit”, destroyed this successful example with its own hands..”

That sentiment — that the Netherlands is treating China unfairly despite Chinese contributions to the Dutch economy and business — was echoed across social media. On the Q&A platform Zhihu, some users called it “a dramatic story”:

💬✍️ “Wingtech spent hundreds of billions of yuan to acquire a long-established European semiconductor company, thinking it had finally gained access to core global technology. But before long, others pulled the rug out from under them, right in front of the whole world.”

Commenter Yan Yaofei (晏耀飞) said:

💬✍️ “It’s like you bought a cow and keep it in someone else’s barn — you tell them how to feed and use it, and they have no right to interfere. Then suddenly, they lock you out of the barn entirely. It basically can be classified as robbery, openly and shamelessly.”

Another Weibo commenter (@就是赵老哥) wrote:

💬✍️ “It feels like the Netherlands is making a fuss. Back then, they sold us a loss-making company and now they’re backing out. This will have a big impact on the semiconductor sector. Foreign companies are unreliable, even when you buy their companies, they’re still unreliable. Domestic substitution is the only way forward.”

Alongside mistrust toward the West and perceptions that the Netherlands has treated China unfairly, even betraying it, many online discussions also frame the move as part of a broader political provocation. At the same time, a recurring theme on social media is the belief that China must strengthen its domestic semiconductor industry.

Finance blogger Tengteng’s Dad (@腾腾爸) wrote:

💬✍️ “The Dutch government’s freezing of the shares of Wingtech Technology’s Dutch subsidiary reminds me of the Ping An–Fortis incident years ago. Europe hasn’t changed, it’s still the same shameless Europe. It’s just that my fellow countrymen have thought too highly of them, thanks to all those “public intellectuals” who have spent years diligently promoting their Western masters. Now, more and more Chinese people are opening their eyes. In the future, all that Western talk about democracy, rule of law, and freedom will completely lose its appeal in China.”

Chinese Narratives of Europe

The online reactions to the Nexperia incident echo broader Chinese narratives about Europe that have been circulating in the digital sphere for the past decade.

Last Thursday, the topic of Chinese narratives of Europe happened to be the main theme of a panel I joined during the ReConnect China Conference in The Hague, hosted by the Clingendael China Centre (event page).

In preparation for this event, I focused mostly on the social media angle of these narratives. I looked at hundreds of trending topics related to Europe from different Chinese platforms—from Kuaishou to Weibo—with a dataset of nearly 100 pages filled with hashtags that went viral over the past twelve months (October 2024–October 2025), to see what themes dominate discussions about Europe in China’s online sphere.

Excluding sports-related topics (which account for about 35–40% of all high-ranking posts about Europe; sports apparently are the best diplomacy tools, after all), the top 250 non-sports topics reveal a clear image of how Europe is perceived in Chinese digital discourse today.

A brief overview:

🟧 1. Energy, Russia, Sanctions, War, Security (≈ 38%)

🔍 Main Focus: Russia–Ukraine war, Europe’s energy crisis, loss of autonomy, European geopolitical vulnerability and dependence on the United States

💡 Main Theme: Europe is often portrayed as lacking strategic autonomy and bearing the heavy costs of decisions driven by Washington’s agenda. It is viewed as vulnerable and “losing out” (吃亏), strategically outmaneuvered & excluded from major geopolitical decision-making.

🟧 2. Economy, Trade, Technology (≈ 21%)

🔍 Main Focus: ASML, tensions over electric vehicles (EVs) and protectionism, supply chains, trade deficits, and deindustrialization

💡 Main Theme: Europe’s trade frictions with China are portrayed as symptoms of Western decline and hypocrisy. The main story is that Europe’s economy is stagnating partly due to being overly protectionist and dependent on the US, while China emerges as a more dynamic and vital global player. Europe is losing competitiveness while China rises as a tech innovator.

🟧 3. EU Politics and Governance (≈ 13%)

🔍 Main Focus: Internal EU divisions, populism, leadership crises, and Europe’s political rightward shift (右倾)

💡 Main Theme: The EU is depicted as disunited and inefficient, struggling to respond to global challenges. The focus is on its inability to achieve strong, unified leadership amid political instability and ideological fragmentation.

🟧 4. Society, Migration, Crime (≈ 11%)

🔍 Main Focus: Social instability, migration, public safety, and racial or cultural tension

💡 Main Theme: Europe is seen as unsafe, chaotic, and socially divided. This is often contrasted with China’s image of order and security.

🟧 5. Culture, History, Sino-European Relations (≈ 10%)

🔍 Main Focus: Cultural comparisons, debates on values, and reflections on historical ties

💡 Main Theme: While Europe is respected for its rich cultural heritage and moral legacy, it is also mocked for its perceived sense of moral superiority. Europe stands for the past glory of civilization, not its future.

🟧 6. Lifestyle, Tourism, Memes (≈ 7%)

🔍 Main Focus: Chinese tourism in Europe, theft incidents, travel diaries, humorous cross-cultural comparisons, and the growing sentiment of being “suddenly disillusioned with Europe” (对欧洲祛魅了)

💡 Main Theme: Europe remains a popular travel destination, but the online tone has shifted from overwhelming admiration to a more pragmatic and critical perspective. The image of Europe is now more “de-romanticized,” with some even suggesting that “getting robbed is part of the experience” [of traveling in Europe] (I previously wrote about that here).

From Chips to Goals

So what does this all tell us?

Beyond the idea that Europe—caught between Washington and Moscow—lacks the agency to handle external crises while also struggling with internal division and decline, the dominant Chinese narrative about Europe is actually not about Europe at all.

‘Europe’ is all about China. Representations of Europe—from “democratic disillusion” to danger, disorder, and dependency—serve as both a mirror and a warning against which Chinese social, political, and national narratives are contrasted: chaos vs. order, fragmentation vs. unity, vulnerable dependency vs. strategic autonomy, decline vs. rise, etc. etc.

Something that the hashtags don’t tell us as much, but is still very much alive as well, is that Europe is also still seen as a major market of opportunities and a crucial soft power frontier for China.

Europe’s future, therefore (and for other reasons), matters to China—not as a model to follow, but as a stage for Chinese cultural and economic influence, where Chinese products, culture, and ideas can shape global appeal.

Perhaps that’s also what gives the Nexperia incident its extra weight: it ties together multiple narratives. Europe is seen as overly protectionist, biased against China, and driven by Washington’s agenda — and the fact that former Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, now NATO Secretary-General, once called US President Trump “daddy” fits into that perception. As some Weibo commenters joked: “Did their daddy make them do it?”

In the end, the takeaway for many commenters is that the incident serves as another “wake-up call for China”: a stark reminder of the need for technological self-reliance. And so, the discussion unfolds in such a way that, once again, it becomes more about China than about Europe — about China’s international strategies, its global rise, and the lessons to be learned, with the Netherlands as the current antagonist.

Thankfully, there was something to celebrate as well: the Netherlands won 4-0 in the popular match against Finland. Amidst all the talk about trade and tech, one popular sports blogger on Weibo vividly wrote about how the Dutch attack was in full force, about how all-time top scorer Memphis Depay led the offense brilliantly, how he helped the team secure a victory, and how the Netherlands “took control of their own destiny in the race to top the group.”

Whatever the future holds for Nexperia and the geopolitical drama surrounding it, at least we can count on the unifying power of football — where, even if only for 90 minutes, chips sit on the bench and netizens far apart in politics cheer for each other’s countries.

I’m not even an avid football fan, but suddenly, the 2026 World Cup (still months away) can’t come soon enough.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

Consumers are profiting from the full-blown delivery war between JD.com and Meituan—but is it just the same game with a different name?

Published

10 months agoon

April 30, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

In April 2025, China’s food delivery sector witnessed a somewhat dramatic development, which attracted major attention online, when Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com publicly challenged food delivery leader Meituan.

On April 21, JD.com posted a noteworthy open letter titled “To All Fellow Food Delivery Rider Brothers” (各位外卖骑手兄弟们) on Weibo. In this letter, they accused Meituan (though not explicitly naming them) of monopolistic practices, after the company allegedly forced their delivery staff to stop accepting JD’s delivery orders. If riders chose to deliver for both companies anyway, they’d risk being blacklisted.

JD therefore accused Meituan of unethical behavior, neglecting their workers’ welfare, and pressuring part-time couriers to choose between platforms.

In their letter, JD vowed to support the freedom of Chinese delivery riders to accept orders from various platforms, and pledged to support those who were being blacklisted by offering them sufficient order volumes and full-time positions with benefits, including employment opportunities for their partners.

The bold move, dubbed the “421 Food Delivery Incident” by netizens, ignited widespread online debate.

“Underdog” JD vs. Meituan: The Start of a New Delivery War

JD.com is a household name in China’s e-commerce industry, best known for its electronics retail business. In recent years, it has expanded into fresh groceries, online supermarkets, and instant delivery services. Meanwhile, China’s food delivery market has long been dominated by Meituan (美团) and Ele.me (饿了么), the latter owned by Alibaba. Before a recent online controversy brought attention to it, many people weren’t even aware that JD had entered the food delivery space.

JD’s entry into China’s thriving food delivery market hasn’t been too long ago—the company officially only announced its JD Waimai (京东外卖) food delivery service back in February this year.

Before JD, other major tech companies like Tencent, Baidu, and ByteDance had all tried (and failed) to challenge the dominance of Meituan and Ele.me. But JD has a strong advantage: a massive logistics system with over 300,000 (!) delivery staff. Its Dada (达达) on-demand delivery and local logistics platform also has nearly 1.3 million active couriers, making JD a serious new competitor in China’s food delivery market. Not surprisingly, JD has already started hiring away talent from Meituan.

Amid JD’s growing presence, a post surfaced in April, reportedly from Meituan executive Wang Puzhong (王莆中), mocking JD’s food delivery ambitions as laughable. He used harsh language, calling JD a “cornered dog” making a desperate move (狗急跳墙). Then, on April 15, Meituan’s Flash Delivery service (美团闪送) released a video teasing JD’s supposedly slow delivery speeds (#美团闪购疑似嘲讽京东#). The video showed a dog with the caption: “Your Dongdong is still on the way” — a direct jab at JD, whose mascot is a dog and whose founder, Richard Liu (Liu Qiangdong), is nicknamed “Dongdong.”

JD swiftly hit back. On April 16, a video from an internal JD meeting was leaked, widely seen as a deliberate PR move. In the video, JD founder Richard Liu criticized the food delivery industry, claiming platforms were making excessive profits while restaurants struggled to survive. “Running a restaurant is already hard, yet platforms—just middlemen—are making a fortune,” he said. Liu added that JD would cap its profit margin at 5% and offer full social insurance to its full-time couriers—setting the tone for the official statement that followed.

Then came JD’s April 21 post, which launched a series of serious accusations against Meituan. JD claimed that Meituan had long restricted part-time couriers from working with other platforms and had failed to provide any social insurance to its full-time riders for over ten years. It also criticized Meituan’s working conditions, accusing the company of exploiting riders through algorithm-driven pressure while ignoring their safety. Additionally, JD accused Meituan of squeezing restaurants for profit, turning a blind eye to unhygienic “ghost kitchens,” and neglecting basic food safety standards. The tone of the post was sharply critical.

The attack prompted Meituan to respond publicly. That same evening, it issued a statement on its official WeChat account, denying that it had ever restricted riders from working with other platforms. Meituan also pushed back by accusing JD of mistreating its own couriers, pointing to heavy fines and unfair internal policies as the real issue.

However, Meituan’s response did little to improve its public image. On Weibo and short-video platforms, public sentiment largely turned against Meituan. That night, a netizen posted that JD CEO Richard Liu himself had delivered their JD order. Stories of Liu chatting with riders and restaurant owners quickly went viral, reinforcing his image as a down-to-earth, working-class hero—and earning JD another wave of goodwill.

At the moment, JD enjoys strong public support—not necessarily because it’s doing everything perfectly, but because it has timed its entry well, casting itself as the underdog taking on Meituan, the widely criticized corporate giant.

The Meituan Backlash

There’s no doubt that Meituan is a true giant. In 2024, the company generated a staggering RMB 300 billion (about $41 billion) in revenue. But this delivery empire has long faced ethical criticism—and JD’s recent accusations on Weibo highlight issues that many in the industry have raised before.

Meituan’s commission rates for restaurants are notoriously high, typically ranging from 15% to 25%. According to reports, around 60% of restaurants on the platform operate at a loss—even as Meituan continues to post multi-billion-yuan profits year after year. Many restaurant owners have voiced their frustration online, saying Meituan initially attracted them with generous onboarding incentives, only to gradually increase commissions, service fees, and so-called “tech support charges.” In the end, even strong sales often fail to translate into real profit. Yet with fierce competition and Meituan’s dominance in the food delivery market, many restaurants feel they have no choice but to stay.

For workers, complaints from Meituan couriers are nothing new. The faster they deliver, the more the algorithm shortens their future delivery windows, while slower deliveries result in fewer order assignments. This creates a vicious cycle, pressuring riders to break traffic rules just to meet deadlines. Unsurprisingly, their accident rate is reported to be three times higher than that of express couriers. To make matters worse, Meituan has historically provided no social insurance—neither for full-time nor part-time riders—leaving them on their own when accidents happen. As some couriers bitterly joke, “We’re not people—we’re just human batteries.”

For consumers, the concerns are just as serious. As I noted in an earlier article, Meituan’s platform increasingly hosts “ghost kitchens”—delivery-only outlets that often operate in unsanitary conditions, producing low-cost, low-quality meals to support Meituan’s Pinhaofan service and fuel ongoing price wars. It’s hard to believe Meituan isn’t aware of these practices; it simply appears to look the other way.

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Meituan’s ethical challenges. But for many users, they’re reason enough to delete the app—especially now that JD has positioned itself as a credible alternative.

Of course, few believe Richard Liu is driven purely by social responsibility—he’s long been skilled at presenting himself as a “man of the people.” In JD’s early days, he famously delivered electronics himself in a three-wheeler. Still, as many netizens have put it: “Judge by actions, not intentions” (君子论迹不论心). Whatever JD’s true motives, its current words and actions seem to align with the interests of ordinary consumers and workers. But the question remains: is that enough?

Different name, same game?

For many consumers, the showdown between JD and Meituan has been surprisingly entertaining, and even financially rewarding. The more intense the rivalry, the bigger the discounts. Netizens have been sharing screenshots of good deals they’ve scored from both platforms in recent days. Some media outlets have even declared, “Richard Liu is saving food delivery and changing the industry for good!”

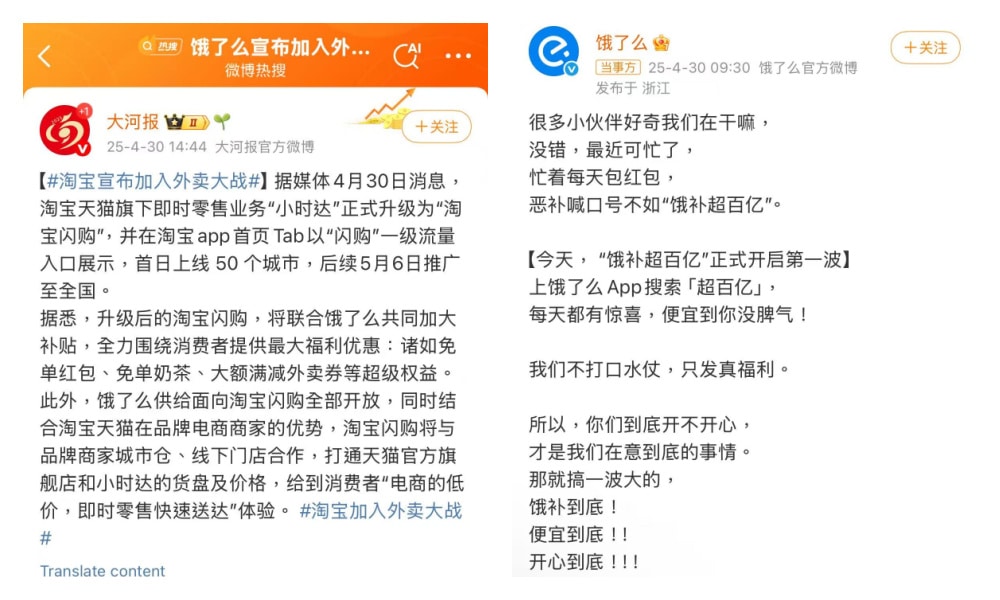

Meanwhile, Taobao and Ele.me have also announced that they’ll be joining the big JD–Meituan showdown by making themselves more competitive. “Taobao Flash Delivery” (淘宝闪购) will now be prominently featured on the main Taobao app, and Taobao and Ele.me will be more closely integrated under Alibaba to offer customers faster delivery times and the best prices. That means more offers—and good news for consumers.

Taobao and Ele.me also join the big battle

But offline, couriers are responding more cautiously. Rider welfare has quickly become a key issue in this corporate battle—and may even become a way for platforms to stand out in a crowded market. But big promises aren’t enough. Only real, visible improvements will earn riders’ trust.

Courier A Ping (阿平) has long been sharing food delivery vlogs online. He used to work for both Meituan and Ele.me. Since April 16, he’s started posting about JD’s delivery platform, and has raised many concerns: part-time riders apparently find it hard to get orders, the system is difficult to navigate, the dispatch logic is flawed, and the navigation is poor.

In the comments section, other couriers are joining the discussion, with many agreeing that JD’s current system only works for full-time employees. “If full-timers get the full benefits, insurance and everything, then it;s probably not that easy to become one,” one wrote. “JD looks promising now, with high pay and benefits, but give it time—it’ll end up the same as the others.”

Another rider, Yu (小于) isn’t too excited about the JD-Meituan feud either. “JD’s fine system is super strict,” he said. “At the end of the day, all these platforms are the same.” Whether JD is just using this moment for PR or genuinely stepping up to take on more social responsibility—only time will tell.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Spring Festival Trend Watch: Gala Highlights, Small-City Travel, and the Mazu Ritual Controversy

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West