China Health & Science

Footage Shows Mysterious Flashes Before Qinghai Earthquake

The flashes of light seen in the sky right before the Qinghai earthquake have become a trending topic on Weibo.

Published

4 years agoon

By

Luke Jacobus

Videos of the January 8th quake, which occurred in Qinghai’s Menyuan county, appear to show several intense flashes of light filling the night sky immediately preceding the quake. The videos have sparked debate among Chinese internet users as to the explanation for the brilliant lights, with some referencing the little-understood phenomenon of “Earthquake Lights.”

On January 8 at approximately 1:45 AM, Menyuan County in the Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in China’s Qinghai Province was struck by a magnitude 6.9 earthquake, damaging several homes and causing minor injuries to four people.

Photos of buildings in the area show shattered wall tiling and window glass, a partial ceiling collapse, and other minor structural damage. The area around the quake’s epicenter is sparsely populated, but tremors could be felt in numerous nearby cities including Zhangye, Wuwei, Jinchang, Lanzhou, and Linxia Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu, as well as causing railway closures along the Qinghai-Tibet and Lanzhou-Qinghai high-speed rail lines, Jiangxi Daily reports.

Source: 中国青年网.

The earthquake was followed by several subsequent quakes, including 5 quakes of lesser magnitude all within the hour.

According to the China Earthquake Administration, the quakes continued into the 9th, with a magnitude 3.2 earthquake recorded in Menyuan county at 0:44 on January 9th.

CCTV footage shot moments before the quake and shared widely on Weibo captured a bright, explosive flash of light, which quickly disappears before a second, shorter flash lights up the night sky, followed immediately by tremors.

This video went viral on Chinese social media this weekend, showing an intense flash of light right before the Qinghai earthquake happened. pic.twitter.com/MtibhGiTSl

— What's on Weibo (@WhatsOnWeibo) January 9, 2022

The footage intrigued Chinese netizens, with the hashtag “Intense Flash of Light on the Horizon Before the Qinghai Earthquake” (#青海地震前地平线出现耀眼强光#) accumulating over 100 million views by Sunday and giving rise to debate over the cause of the strange lights. Other videos capturing the flash from different angles show only one flash, or several smaller flashes along the horizon.

Much of the debate centered around whether this was a case of “Earthquake Lights” (地光/地震光, also EQLs), a controversial phenomenon among scientists which is sometimes reported before high-magnitude earthquakes, such as Italy’s 2009 L’Aquila quake.

Just before and after quakes begin, witnesses have reported seeing unexplainable light phenomena in a range of colors, ranging from brilliant white flashes as bright as daylight to a blue, flame-like glow hovering above the earth.

Explanations range from the ionization of oxygen in rocks under intense stress, piezoelectric or triboluminescent phenomena, and leaks of radioactive ionizing gas into the atmosphere to more mundane sources, such as the flailing of damaged power lines. Sometimes the lights were also said to come from UFOs or explained them in religious terms, but a 2014 study refuted this and linked the phenomenon to rift environments.

Interestingly, this is not the first time the phenomenon has been reported to precede a major earthquake in China. Some Weibo users remarked that “Earthquake Lights” had been seen before the disastrous 1976 Tangshan earthquake, which damaged or destroyed vast swathes of that city and killed over 240,000 people. Two movies depicting the quake, After the Blue Light Flashes.. (蓝光闪过之后..) and The Great Tangshan Earthquake (唐山大地震) both feature scenes of mysterious bright lights illuminating the night sky moments before tremors began.

Strange lights were also reported in the sky in Tianshui, Gansu province, preceding the 2008 Sichuan earthquake.

Other Weibo users remained unconvinced about the strange lights being mysterious Earthquake Lights. “Don’t freak out over it,” one user wrote: “It’s just a downed power line.”

Another online video features commentary from seismologist Chen Huizhong (陈会忠) of the China Earthquake Administration, who explains the flashes as an electrical transformer exploding, noting that footage from another angle shows the tremors damaging electrical lines in the distance, which begin sparking and showing obvious signs of damage. This damage, however, occurs after the tremors have already started, and does not seem to explain the bright flashes which lit up the sky immediately preceding the tremors.

Still others suggested that radon gas leaking from underground as the earth shifted could have caused the flash.

While the debate rages on between proponents and skeptics of “Earthquake Lights,” a third group of online commenters has already made up their minds: the Weibo fans of prominent Chinese science fiction writer and The Three-Body Problem author Liu Cixin (刘慈欣), wasted no time in heralding the coming of extraterrestrial invaders.

“Looking forward to a scientific explanation,” wrote one user: “As for me, I think it’s the first step in an alien attack.” The user’s post ended with the hashtag, “The Sophon from Three-Body Problem has arrived!”

By Luke Jacobus

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Luke Jacobus is a sophomore Mandarin / International Studies double major at the University of Mississippi's Chinese Flagship Program. Jacobus is passionate about China's popular culture, cinema, and online media.

You may like

China Animals

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

“We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

Published

2 months agoon

October 5, 2025

China is facing a serious donkey shortage. China’s donkey population is far below market demand, and the prices of donkey-related products continue to rise.

Recently, this issue went trending on Weibo under hashtags such as “China Currently Faces a Donkey Crisis” (#我国正面临缺驴危机#).

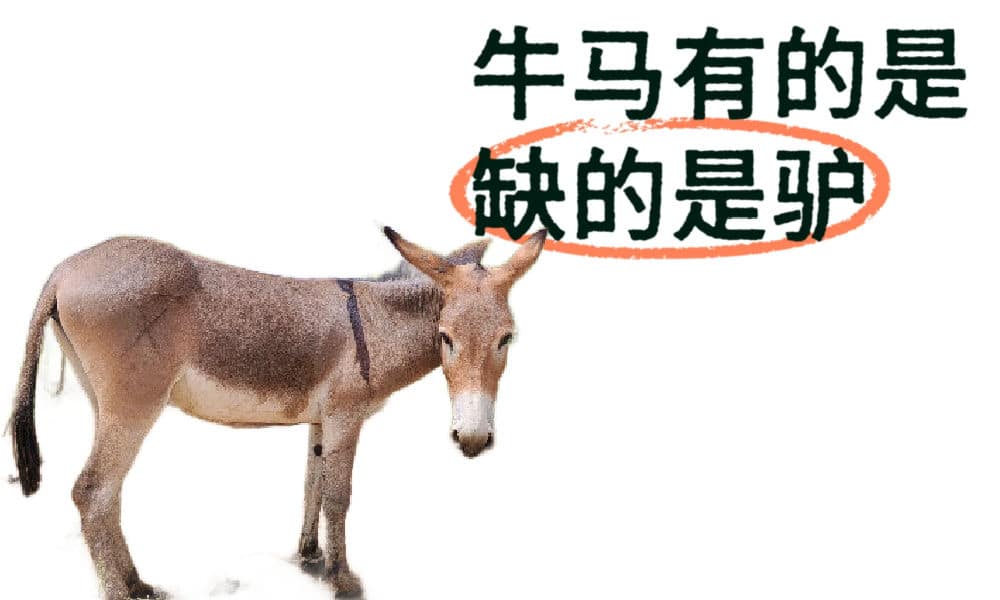

The Donkey Branch of China’s Livestock Association (中国畜牧业协会驴业分会) addressed this issue in Chinese media earlier last week, telling China News Weekly (中国新闻周刊): “We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

China’s donkey population has plummeted by nearly 90% over the past decades, from 11.2 million in 1990 to just 1.46 million in 2023.

The massive drop is related to the modernization of China’s agricultural industry, in which the traditional role of donkeys as farming helpers — “tractors” — has diminished. As agricultural machines took over, donkeys lost their role in Chinese villages and were “laid off.”

Donkeys also reproduce slowly, and breeding them is less profitable than pigs or sheep, partly due to their small body size.

Since 2008, Africa has surpassed Asia as the world’s largest donkey-producing region. Over the years, China has increasingly relied on imports to meet its demand for donkey products, with only about 20–30% of the donkey meat on the market coming from domestic sources.

China’s demand for donkeys mostly consists of meat and hides. As for the meat — donkey meat is both popular and culturally relevant in China, especially in northern provinces, where you’ll find many donkey meat dishes, from burgers to soups to donkey meat hotpot (驴肉火锅).

However, the main driver of donkey demand is the need for hides used to produce Ejiao (阿胶) — a traditional Chinese medicine made by stewing and concentrating donkey skin. Demand for Ejiao has surged in recent years, fueling a booming industry.

China’s dwindling donkey population has contributed to widespread overhunting and illegal killings across Africa. In response, the African Union imposed a 15-year ban on donkey skin exports in February 2023 to protect the continent’s remaining donkey population.

As a result of China’s ongoing “donkey crisis,” you’ll see increased prices for donkey hides and Ejiao products, and oh, those “donkey meat burgers” you order in China might actually be horse meat nowadays. Many vendors have switched — some secretly so (although that is officially illegal).

Efforts are underway to reverse the trend, including breeding incentives in Gansu and large-scale farms in Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang.

China is also cooperating with Pakistan, one of the world’s top donkey-producing nations, and will invest $37 million in donkey breeding.

However, experts say the shortage is unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

The quote that was featured by China News Weekly — “We have cows and horses, but no donkeys” (“牛马有的是,就缺驴”) — has sparked viral discussion online, not just because of the actual crisis but also due to some wordplay in Chinese, with “cows and horses” (“牛马”) often referring to hardworking, obedient workers, while “donkey” (“驴”) is used to describe more stubborn and less willing-to-comply individuals.

Not only is this quote making the shortage a metaphor for modern workplace dynamics in China, it also reflects on the state media editor who dared to feature this as the main header for the article. One Weibo user wrote: “It’s easy to be a cow or a horse. But being a donkey takes courage.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Health & Science

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

After realizing domestic sanitary pads were literally falling short, Chinese netizens are demanding greater awareness and improvements in long-overlooked issues of quality, affordability, and societal attitudes toward menstruation.

Published

12 months agoon

December 6, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Sanitary pads have never been a bigger topic of debate on Chinese social media as it’s been over the past few weeks. What began with one blogger’s discovery of menstrual pads falling short of their advertised size has grown into a broader movement, demanding better-quality products and greater awareness of menstrual health.

Despite being a natural part of life for women around the world, menstruation remains a sensitive and taboo subject in many parts of China, particularly in more conservative, rural areas and smaller cities.

Essential feminine hygiene products like sanitary pads or tampons are often discreetly wrapped in dark plastic bags to avoid drawing attention.

However, this month, the silence was broken. “Sanitary pads” and related topics dominated online discussions, igniting a heated conversation that started with pad length but quickly expanded to include concerns about health, safety, and women’s rights.

EXPOSING THE “SHORTCOMINGS” IN SANITARY PADS

“Buy it if you want, or just don’t.”

In early November, a viral post on Xiaohongshu (later deleted) brought attention to a troubling issue. A woman who purchased sanitary pads online found them significantly shorter than advertised—a supposed 290mm pad measured only 250mm.

When she confronted the seller, they dismissed her concerns, citing a “normal 4% margin of error” and claiming, “If you order 290mm, we can only send 250mm—that’s the rule.”

The post struck a nerve. Netizens began measuring their own pads and discovered that many brands similarly fell short of their advertised lengths. This perceived deception ignited widespread outrage:

“They market themselves as designed for women, but even the lengths are misleading?”

“We pay the highest taxes for subpar products!”

The controversy soon spread to platforms like Douban and Weibo, where more and more people started comparing advertised versus actual pad lengths. The results revealed that many well-known brands consistently fell short, raising accusations of industry-wide cost-cutting.

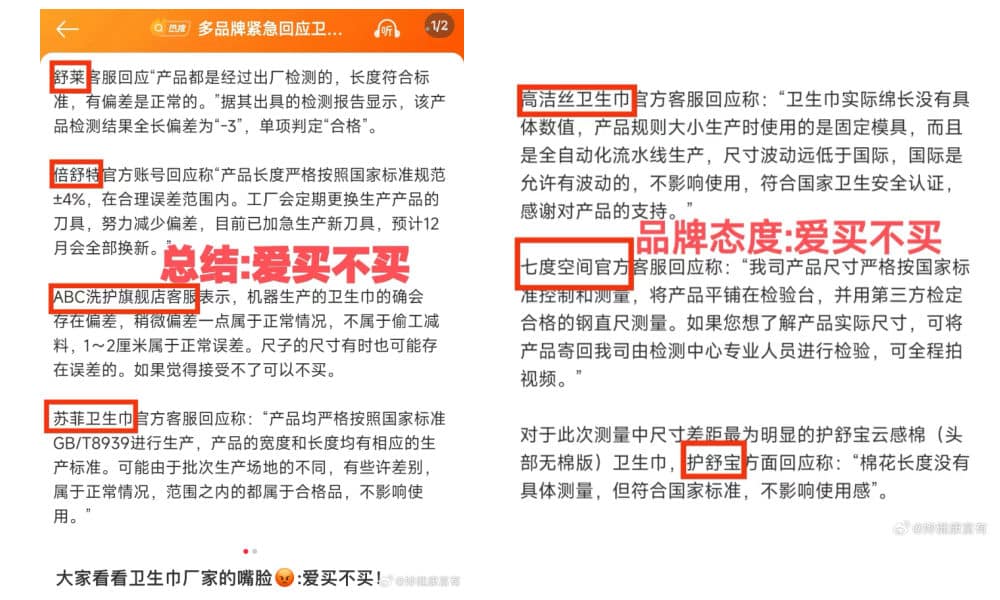

Facing mounting pressure, several Chinese brands issued responses claiming their products adhered to the national standard that allows a ±4% length deviation. According to this standard, a 290mm pad can legally measure between 278mm and 302mm.

However, consumer measurements consistently showed pads at the lower limit—or even shorter. This raised suspicions that manufacturers were exploiting the -4% allowance as an industry norm to cut costs.

Some netizens compiled a crowdsourced chart comparing the advertised length, actual length, and cotton coverage of various brands. The findings revealed similar discrepancies across major brands.

Various brands’ responses to the controversy listed by blogger @妳健康富有.

Some brands, with size deviations as large as -15%, responded evasively to consumer concerns, claiming that such deviations are normal and do not affect usage. These responses only fueled further frustration among netizens, who accused the brands of dismissing their concerns. As one blogger (@你健康富有) remarked, the brands’ attitude couldn’t be clearer: “‘Buy it if you want, or just don’t.'”

BEYOND LENGTH: A DEEPER ISSUE

“Society tolerates or even reinforces menstrual stigma.”

While the pad length scandal initially focused on cost-cutting, the ensuing discussions uncovered far more serious concerns. A resurfaced video by documentary filmmaker and blogger Fourfire (四火, @为了玲飞护肤纪录片) revealed the industry’s dark side. The video exposed illegal factories recycling used materials, including shredded pads and diapers, into new sanitary products. These contaminated pads, sold cheaply on e-commerce platforms, have been linked to pelvic inflammation and other gynecological problems.

In the video, Fourfire urged women to stick to well-known brands and purchase from reputable retailers.

Still from the video by documentary filmmaker and blogger Fourfire (四火, @为了玲飞护肤纪录片)

But are pricier pads from major retailers truly safe? Quality issues with domestic brands have surfaced repeatedly, and this latest length discussion reignited those concerns. Consumer-created “red-flagged brands” for domestic pads feature numerous well-known brands with prior reports of containing maggots, mold, and other contaminants.

This renewed scrutiny prompted questions and discussions among female netizens. One user asked, “Is there any brand of sanitary pads that’s actually safe to use?” Among the hundreds of replies and shares, one prevailing sentiment emerged: “None of them.” Many users began to view previous quality issues not as isolated incidents but as indicative of broader problems within the industry.

Adding fuel to the fire, one blogger (@迷宝吃不饱) claimed that the national standards for sanitary pads in China allow a pH range of 4–9. This range aligns with standards for non-intimate textiles, such as jackets or curtains. Given that human skin is slightly acidic, with a pH between 4.1 and 5.8 (3.8–4.5 for intimate zones), products in close contact with the skin, such as sanitary pads, should ideally be designed to maintain the skin’s natural pH balance and prevent irritation.

This seemingly loose standard sparked further concerns among female consumers. Many began reflecting on their past experiences, sharing issues they’d faced while using sanitary pads—frequent inflammation, allergic reactions, itching, and other symptoms. Few had considered the possibility that these problems might be linked to the pads themselves.

In response, experts argued that the materials, hygiene, and sterilization of pads were far more critical than pH levels. However, in today’s China, where public trust in such authorities is relatively low (read: “Experts Are Advised Not to Advise“), this explanation not exactly reassured the public. Gynecologists and popular science influencers, such as Sixthfloor (@六层楼先生), pointed out that similar products like baby diapers and men’s sanitary pads are held to stricter production standards. This disparity naturally fueled suspicion and concern about women being disadvantaged and the role of societal taboos surrounding menstruation.

One Douban user commented: “Society tolerates or even reinforces menstrual stigma. The less we talk about sanitary pads, the easier it is for companies to profit from women.”

BREAKING THE SILENCE

“Decisions about menstrual products are being made by people who don’t menstruate.”

Sanitary pads in China are relatively expensive and not covered by health insurance. A single daytime pad from a common brand costs around 1 RMB ($0.15), while nighttime pads can be twice as expensive. Over a typical six-day period, a woman might spend 30-40 RMB ($4.15-$5.50) each month. Tampons, though less popular in China, are even more costly.

For women in impoverished or rural areas, this expense can be a significant burden. Many are forced to purchase low-cost, unregulated “three-no” products (no license, no standards, no brand), often manufactured by the shady companies exposed in Fourfire’s video. On Taobao, product reviews for these pads reveal heartbreaking stories. Some users recommend switching to safer, higher-quality options, but responses often reflect the harsh reality: “I don’t have a choice.”

Now, as major brands face public backlash, many women are turning to “medical-grade sanitary pads,” originally made for surgical recovery or heavy bleeding. According to the Sichuan Observation media channel (@四川观察), online searches for these products have jumped by over 3,000%. While safer, these pads are even more expensive.

The frustration is clear: “Do we really have to keep paying more for basic necessities just to protect our health? Why not just make regular sanitary pads safe and reliable? Is that too much to ask?”

So why is it so hard to produce affordable, safe sanitary pads without cost-cutting tricks? The answer may lie in a regulatory change made over a decade ago. In 2008, new national standards for sanitary pads eliminated quality grading classifications and reduced minimum requirements for the length of filling cotton. This gave manufacturers more freedom to cut costs, often at the expense of quality.

One glaring detail hasn’t gone unnoticed: the revised standards were drafted entirely by men. As one netizen commented, “Decisions about menstrual products are being made by people who don’t menstruate.” For women, the lack of female representation in an industry directly affecting them is both absurd and infuriating, highlighting a deeper issue of gender imbalance in industries and regulatory frameworks that shape women’s lives.

At the time of writing, distrust in domestic sanitary pad brands in China has reached a peak. Whether driven by exaggerated fears or valid concerns, one thing is clear: after years of menstrual stigma and neglect of women’s health issues, many women feel unheard and are now speaking out. This growing frustration has given rise to an online feminist movement, calling for accountability and demanding change from an industry—and a culture—that has long overlooked some of women’s basic rights.

GRASSROOTS EFFORTS FOR CHANGE

“Girls should never feel ashamed of their periods”

With policymakers mostly male, Chinese women have had to take matters into their own hands. Over the years, various incidents related to menstrual products have gone viral and triggered grassroots efforts to improve the status quo.

The last major public outcry about sanitary pads occurred in 2022 when a woman on a high-speed train discovered they weren’t available for purchase. She vented her frustration online, and the issue quickly gained traction. Many commenters, mostly men, argued that pads weren’t “essential items” and didn’t warrant taking up retail space onboard. The railway authority’s official response—categorizing sanitary pads as “personal items” that didn’t need to be sold—only intensified the outrage.

In the same year, a young woman in Covid quarantine in Xi’an went viral after she tearfully begged anti-epidemic staff for sanitary pads. When workers at her quarantine hotel told her there was nothing they could do, she asked, “So what? Does that mean I have to bleed a river of blood?”

For many women, these incidents highlighted how little society understands or respects their basic needs. In response, people organized online campaigns, flooded hotlines with complaints, and raised awareness about why menstrual products are essential. “Girls should never feel ashamed of their periods,” one netizen wrote.

Sometimes, progress is made. The woman in Xi’an’s quarantine later posted an update, saying she eventually received the menstrual pads she needed. And although pads are still not available on all high-speed trains, they are now provided on many routes—a small but meaningful step.

This time, the debate over pad quality has drawn even greater attention, involving public figures, celebrities, and even tech mogul and Xiaomi founder Lei Jun (雷军), with some hoping that a trusted brand like Xiaomi could play a role in making Chinese sanitary pads safer and more innovative. Women have launched cross-platform campaigns like #ShowYourSanitaryPads (#晒出你的卫生巾#), encouraging people to share posts on Weibo, Douban, and Xiaohongshu to call out brands for inaccurate sizing or poor quality.

Activists are also sharing step-by-step guides on filing formal complaints and advocating for stricter national production standards. The movement is gaining momentum, driven by a collective determination to demand safer, more reliable products.

On November 21, China News Weekly reported that a new national standard for sanitary pads is being drafted. CNR News also called for tighter industry oversight, signaling an urgent response to recent public criticism.

Yet, this response only scratches the surface of the deeper issues surrounding menstrual products in China. Challenges such as the high cost of pads, their limited availability in public spaces, and inadequate menstrual education persist. Will meaningful change continue to rely solely on grassroots efforts? Hopefully, this marks the beginning of a broader, systemic shift that not only addresses these immediate concerns but also redefines how society values and prioritizes women’s basic needs.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral5 months ago

China Memes & Viral5 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital11 months ago

China Digital11 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained