China Insight

‘Sharenting’ on Chinese Social Media: When Parents Are Posting Too Many Baby Pics on WeChat

‘Shaiwa’ is the Chinese term for ‘Sharenting’ – when does sharing baby pictures on social media become too much?

Published

7 years agoon

WHAT’S ON WEIBO ARCHIVE | PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

First published

It’s called ‘Sharenting’ in English, it’s called ‘Shàiwá’ in Mandarin Chinese, and it’s all about parents sharing (too) many photos of their offspring on social media.

To what extent is it okay to post photos of your baby or children on social media, and when does it become too much? These questions are at the heart of a discussion that has been ongoing on Chinese social media recently, with the hashtag “Should You Be Sharenting on Moments?” (#朋友圈该不该晒娃#) receiving 140 million views on Weibo.

‘Moments’ is WeChat’s social-networking function, that allows users to share photos on their own feed that is visible to their friends, family, and other Wechat contacts.

‘Sharenting’ is a word that was coined to describe the overuse of social media by parents to share content based on their children. Around 2013/2014, the word came to be used more frequently in English-language mainstream media. In Chinese, the term for this phenomenon is ‘shài wá‘ (晒娃), which combines the characters for ‘exposing’ and ‘babies.’

Recently, more articles have popped up in Chinese media that take a critical stance towards parents sharing too much about their children on social media, with some WeChat Moments feeds consisting entirely of photos of children.

Sharenting Concerns

In English-language media and academic circles, the phenomenon of ‘sharenting’ has been a topic of discussion for years. In 2017, Blum-Ross and Livingstone published a study about the phenomenon, highlighting the concerns over it.

Some of these concerns are that ‘sharenting’ might infringe on children’s right to privacy, that it can be exploitative, is possibly exposing children to pedophiles, and might have consequences in terms of data-mining and facial recognition (110).

For parents, the reasons to share photos of their children online are multifold. It could just be to chronicle their lives and share with friends and relatives, but it could also be because they are part of (online) communities where sharing these photos is part of the shared lifestyle and identity (Blum-Ross & Livingstone 2017, 113).

For some, it is a way to express their creativity and this might also lead to some parents gaining financial benefits from doing so, if they are, for example, bloggers incorporating advertisements or sponsored content on their channels.

Recently, the topic became much discussed in the US after actress Gwyneth Paltrow posted a picture on Instagram in late March of her and her 14-year-old daughter Apple Martin skiing. Apple then responded in the comments sections, saying: “Mom, we have discussed this. You may not post anything without my consent.” The incident sparked discussions on children’s privacy on social media.

Whose Choice Is It?

In China, there is not just a word for ‘sharenting,’ there is even a word to describe parents who ‘sharent’ like crazy: Shàiwá Kuángmó (晒娃狂魔), meaning something like ‘Sharenting Crazy Devils.’

The phenomenon of sharenting was discussed in Chinese media as early as 2012, when it was mostly the safety issue of ‘sharenting’ that was highlighted: with parents posting photos of their children, along with a lot of personal information, they might unknowingly expose their children to child traffickers, who will easily find out through social media where a child goes to school, and when their parents take them to the park to play.

Recently, discussions on sharenting in China have mainly focused on WeChat as a platform where parents not just post photos of their children, but also post about their school results, their class rankings, and other detailed information. Especially during holidays, WeChat starts flooding with photos of children.

Image via Sina.com

Chinese educational expert Tang Yinghong (唐映红) commented on the issue in a news report by Pear Video, saying that sharenting is a sign of parents missing a certain sense of meaning in their own lives, and letting their children make up for this. Regularly posting about their children’s lives and activities allegedly gives them a certain value, status, and identity.

That they are infringing on the privacy of their children by doing so, Tang argues, is something that a lot of Chinese parents do not even consider. Only if the children agree with their parents sharing their photos, he says, it is okay to do so.

But the majority of commenters do not agree with Tang’s views at all. “So what else are we supposed to post in our ‘Moments’? If we post about our kids, it’s sharenting. If we post about our travels, it’s flaunting wealth. If we post selfies, it’s vanity. We should be free to post what we want in our Moments.”

“Showing off our kids is our own choice, if you don’t want to see it, just block it,” others say.

“He’s not right in what he says. I regularly post my child’s picture. My career is going well and I am happy. The goal of me posting these photos is to keep my WeChat Moments feed alive, and I use it as some sort of photo album,” another Weibo user says.

Some voices do agree with Tang, saying: “First ask your children for permission, they also have their right to privacy.”

Kids’ Rights to Privacy

But what if the children are too young to give permission? And from what age are they able to really give their consent? The idea of children’s ‘right to privacy’ is a fairly new one in Chinese debates on sharenting. In other countries, these discussions started years ago.

In the Netherlands, sociologists Martje van Ankeren and Katusha Sol argued in a 2011 newspaper article that parents posting photos of their babies and young children on social media are actually infringing on the privacy of their kids, disregarding what sharing the lives of their offspring online might mean for them in the future, just for scoring a few ‘likes’ on Facebook.

The online presence of children often starts from the day they are born now, building throughout their whole childhood. A 2017 UK news article suggested that the average parent shares almost 1,500 images of their child online before their fifth birthday. The baby’s first steps, medical issues, ‘funny’ photos and videos of a child with food smeared all over its face – it’s all out there. But what happens to all these online records?

Van Ankeren and Sol argue that the social media presence of children might affect them in the future. What if they are applying for their dream job, but their potential future employee finds out through online research that they had serious health issues as a child? And how do young adults feel about their new friends and acquaintances being able to view all those embarrassing photos of them as a child that their parents ‘tagged’ them in from before they could even remember?

“Everyone should have the right to choose what kind of information they want to share, and with whom. If your parents already did that for you, you lost your freedom of choice before you were even able to consider it,” Van Ankeren and Sol write.

The case of France made headlines last year, as its privacy laws make it possible for grown-up children to sue their parents for posting photos of them on social networks without their consent, which could potentially result in hefty fines or imprisonment.

In China, the debate on kids’ rights to privacy is not yet gaining much attention within the ‘sharenting’ discussions. Some people, however, do speak out about the issue on social media.

“I understand you want to share pictures of your child on ‘Moments’,” one Weibo user (@寒月之瞳) writes: “However, why do you insist on [also] sharing nude photos of your child? Small kids are also people, they have a right to privacy. The people on your ‘Moments’ are not all people you know very well. Do you really think it’s a good idea to share these photos?”

An article in the Chinese Baby Sina outlet writes: “Parents have to protect the privacy of their kids, before posting a photo of them on the internet, think about how it might influence them.”

For most commenters on Chinese social media, however, posting pictures of their children online is just an innocent pastime: “I post on WeChat Moments every day. If it’s not photos of my child, I post about the dinner I cooked or the parties I attend. WeChat Moments is about sharing your life, and in my life, my child is what matters most. It’s only natural that most of my photos are of my child.”

“People shouldn’t meddle in other’s people’s business. Whether or not I want to post my child’s photos is up to me.”

By Manya Koetse

References

Blum-Ross, Alicia and Sonia Livingstone. 2017. “”Sharenting,” Parent Blogging, and the Boundaries of the Digital Self.” Popular Communication 15 (2): 110-125.

Van Ankeren, Martje and Katusha Sol. 2011. “Willempje wil geen Facebookpagina.” Nov 2, NRC: 12.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform resurfaces in Africa, a new winter hotspot, why Chinese elites ‘run’ to Tokyo, and more.

Published

3 months agoon

November 21, 2025

🌊 Signals — Week 47 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China, Signals highlights slower trends and online currents behind the daily scroll. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Different from the China Trend Watch (check the latest one here if you missed it), this edition, part of the new Signals series, is about the slower side of China’s social media: the recurring themes and underlying shifts that signal broader trends beyond the quick daily headlines. Together with the deeper dives, the three combined aim to give you clear updates and a fuller overview of what’s happening in China’s online conversations & digital spaces.

For the coming two weeks, I’ll be traveling from Beijing to Chongqing and beyond (more on that soon) so please bear with me if my posting frequency dips a little. I’ll be sure to pick it up again soon and will do my best to keep you updated along the way. In the meantime, if you know of a must-try hotpot in Chongqing, please do let me know.

In this newsletter: Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform in Angola, a new winter hotspot, discussions on what happens to your Wechat after you die, why Chinese elites rùn to Tokyo, and more. Let’s dive in.

- 💰 The richest woman in China, according to the latest list by Hurun Research Institute, is the “queen of pharmaceuticals” Zhong Huijuan (钟慧娟) who has accumulated 141 billion yuan (over 19 billion USD). Women account for over 22% of Chinese billionaires (those with more than 5 billion RMB), underscoring China’s globally leading position in producing wealthy female entrepreneurs.

- 🧩 What happens to your WeChat after you die? A user who registered for NetEase Music with a newly reassigned phone number unexpectedly gained access to the late singer Coco Lee’s (李玟) account, as the number had originally belonged to her. The incident has reignited debate over how digital accounts should be handled after death, prompting platforms like NetEase and Tencent to reconsider policies on long-inactive accounts and take stronger measures to protect them.

- 📱 Although millions of viewers swoon over micro-dramas with fantasy storylines where rich, powerful men win over the “girl next door” through money and status, Chinese regulators are now stepping in to curb exaggerated plots featuring the so-called “dominant CEO” (霸道总裁) archetype, signaling stricter oversight for the booming short drama market.

- ☕ A popular Beijing coffee chain calling itself “People’s Cafe” (人民咖啡馆), with its style and logo evoking nationalist visual nostalgia, has changed its name after facing criticism for building its brand – including pricey coffee and merchandise – on Mao era and state-media political connotations. The cafe is now ‘Yachao People’s Cafe’ (要潮人民咖啡馆).

- 👀 Parents were recently shocked to see erotic ads appear on the Chinese nursery rhymes and children’s learning app BabyBus (宝宝巴士), which is meant for kids ages 0–8. BabyBus has since apologized, but the incident has sparked discussions about how to keep children safe from such content.

- 🧧The 2026 holiday schedule has continued to be a big topic of conversation as it includes a 9-day long Spring Festival break (from February 15 to February 23), making it the longest Lunar New Year holiday on record. The move not only gives people more time for family reunions, but also gives a huge boost to the domestic travel industry.

Hasan Piker’s Chinese Tour & The US–China Content Honeymoon

Livestreamer Hasan Piker during his visit to Tiananmen Square flag-rising ceremony.

It’s not time for the end-of-year overviews just yet – but I’ll already say that 2025 was the US–China ‘honeymoon’ year for content creation. It’s when China became “cool,” appealing, and eye-grabbing for young Western social media users, particularly Americans. The recent China trip of the prominent American online streamer Hasan Piker fits into that context.

This left-wing political commentator also known as ‘HasanAbi’ (3 million followers on Twitch, recently profiled by the New York Times) arrived in China for a two-week trip on November 11.

Piker screenshot from the interview with CGTN, published on CGTN.

His visit has been controversial on English-language social media, especially because Piker, known for his criticism of America (which he calls imperialist), has been overly praising China: calling himself “full Chinese,” waving the Chinese flag, joining state media outlet CGTN for an interview on China and the US, and gloating over a first-edition copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao (the Little Red Book). He portrays China as heavily misrepresented in the West and as a country the United States should learn from.

Hasan Piker did an interview with CGTN, posing with Li Jingjing 李菁菁.

During his livestreaming tour, Hasan, who is nicknamed “lemonbro” (柠檬哥) by Chinese netizens, also joined Chinese platforms Bilibili and Xiaohongshu.

But despite all the talk about Piker in the American online media sphere, online conversations, clicks, and views within China are underwhelming. As of now, he has around 24,000 followers on Bilibili, and he’s barely a topic of conversation on mainstream feeds.

Piker’s visit stands in stark contrast to that of American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins), who toured China in March. With lengthy livestreams from Beijing to Chongqing, his popularity exploded in China, where he came to be seen by many as a representative of cultural diplomacy.

IShowspeed in China, March 2025.

IShowSpeed’s success followed another peak moment in online US–China cultural exchange. In January 2025, waves of foreign TikTok users and popular creators migrated to the Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu amid the looming TikTok ban.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against Trump and US policies. In a playful act of political defiance, they downloaded Xiaohongshu to show they weren’t scared of government warnings about Chinese data collection. (For clarity: while TikTok is a made-in-China app, it is not accessible inside mainland China, where Douyin is the domestic version run by the same parent company).

The influx of foreigners — who were quickly nicknamed “TikTok refugees” — soon turned into a moment of cultural celebration. As American creators introduced themselves, Chinese users welcomed them warmly, eager to practice English and teach newcomers how to navigate the app. Discussions about language, culture, and societal differences flourished. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor. It was a rare moment of social media doing what we hope it can do: connect people, build bridges, and replace prejudice with curiosity.

Some of that same enthusiasm was also visible during IShowSpeed’s China tour. Despite the tour inevitably getting entangled with political and commercial interests, much of it was simply about an American boy swept up in the high energy of China’s vibrant cities and everything they offer.

Different from IShowSpeed, who is known for his meme-worthy online presence, Piker is primarily known for his radical political views. His China enthusiasm feels driven less by cultural curiosity and more by his critique of America.

Because of his stances — such as describing the US as a police state — it’s easy for Western critics to accuse him of hypocrisy in praising China, especially after a brief run-in with security police while livestreaming at Tiananmen Square.

Seen in broader context, Piker’s China trip reflects a shift in how China is used in American online discourse.

Before, it was Chinese ‘public intellectuals’ (公知) who praised the US as a ‘lighthouse country’ (灯塔国), a beacon of democracy, to indirectly critique China and promote a Western modernization model. Later, Chinese online influencers showcased their lives abroad to emphasize how much ‘brighter the moon’ was outside China.

In the post-Covid years, the current reversed: Western content creators, from TikTok influencers to political commentators, increasingly use China to make arguments that are fundamentally about America.

Between these cycles, authentic cultural curiosity gets pushed to the sidelines. The TikTok-refugee moment in early January may have been the closest we’ve come in years: a brief window where Chinese and American users met each other with curiosity, camaraderie, and creativity.

Hasan’s tour, in contrast, reflects a newer phase, one where China is increasingly used as a stage for Western political identity rather than a complex and diverse country to understand on its own terms. I think the honeymoon phase is over.

“Liu Sihan, Your School Uniform Ended Up in Angola”: China’s Second-Hand Clothing in Africa

A Chinese school uniform went viral after a Chinese social media user spotted it in Angola.

“Liu Sihan, your schooluniform is hot in Africa” (刘思涵你的校服在非洲火了) is a sentence that unexpectedly trended after a Chinese blogger named Xiao Le (小乐) shared a video of a schoolkid in Angola wearing a Chinese second-hand uniform from Qingdao Xushuilu Primary School, that had the nametag Liu Sihan on it.

The topic sparked discussions about what actually happens to clothing after it’s donated, and many people were surprised to learn how widely Chinese discarded clothing circulates in parts of Africa.

Liu Sihan’s mother, whose daughter is now a 9th grader in Qingdao, had previously donated the uniform to a community clothing donation box (社区旧衣回收箱) after Liu outgrew it. She intended it to help someone in need, never imagining it to travel all the way to Africa.

In light of this story, one netizen shared a video showing a local African market selling all kinds of Chinese school items, including backpacks, and people wearing clothing once belonging to workers for Chinese delivery platforms. “In Africa, you can see school uniforms from all parts of China, and even Meituan and Eleme outfits,” one blogger wrote.

When it comes to second-hand clothing trade, we know much more about Europe–Africa and US–Africa flows than about Chinese exports, and it seems there haven’t been many studies on this specific topic yet. Still, alongside China’s rapid economic transformations, the rise of fast fashion, and the fact that China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of textiles, the country now has an enormous abundance of second-hand clothing.

According to a 2023 study by Wu et al. (link), China still has a long way to go in sustainable clothing disposal. Around 40% of Chinese consumers either keep unwanted clothes at home or throw them away.

But there may be a shift underway. Donation options are expanding quickly, from government bins to brand programs, and from second-hand stores to online platforms that offer at-home pickup.

Chinese social media users posting images of school/work uniforms from China worn by Africans.

As awareness grows around the benefits of donating clothing (reducing waste, supporting sustainability, and the emotional satisfaction of giving), donation rates may rise significantly. The story of Liu Sihan’s uniform, which many found amusing, might even encourage more people to donate. And if that happens, scenes of African children (and adults) wearing Chinese-donated clothes may become much more common than they now are.

Laojunshan: New Hotspot in Cold Winter

Images from Xiaohongshu, 背包里的星子, 旅行定制师小漾

Go to Zibo for BBQ, go to Tianshui for malatang, go to Harbin for the Ice Festival, cycle to Kaifeng for soup dumplings, or head to Dunhuang to ride a camel — over recent years, a number of Chinese domestic destinations have turned into viral hotspots, boosted by online marketing initiatives and Xiaohongshu influencers.

This year, Laojunshan is among the places climbing the trending lists as a must-visit spot for its spectacular snow-covered landscapes that remind many of classical Chinese paintings. Laojunshan (老君山), a scenic mountain in Henan Province, is attracting more domestic tourists for winter excursions.

Xiaohongshu is filled with travel tips: how to get there from Luoyang station (by bus), and the best times of day to catch the snow in perfect light (7–9 AM or around 6–6:30 PM).

With Laojunshan, we see a familiar pattern: local tourism bureaus, state media, and influencers collectively driving new waves of visitors to the area, bringing crucial revenue to local industries during what would otherwise be slower winter months.

WeChat New Features & Hong Kong Police on Douyin

🟦 WeChat has been gradually rolling out a new feature that allows users to recall a batch of messages all at once, which saves you the frantic effort of deleting each message individually after realizing you sent them to the wrong group (or just regret a late-night rant). Many users are welcoming the update, along with another feature that lets you delete a contact without wiping the entire chat history. This is useful for anyone who wants to preserve evidence of what happened before cutting ties.

🟦The Hong Kong Police Force recently celebrated its two-year anniversary on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), having accumulated nearly 5 million followers during that time. To mark the occasion, they invited actor Simon Yam to record a commemorative video for their channel (@香港警察). The presence of the Hong Kong Police on the Chinese app — and the approachable, meme-friendly way they’ve chosen to engage with younger mainland audiences — is yet another signal of Hong Kong institutions’ strategic alignment with mainland China’s digital infrastructure, a shift that has been gradually taking place. The anniversary video proved popular on Douyin, attracting thousands of likes and comments.

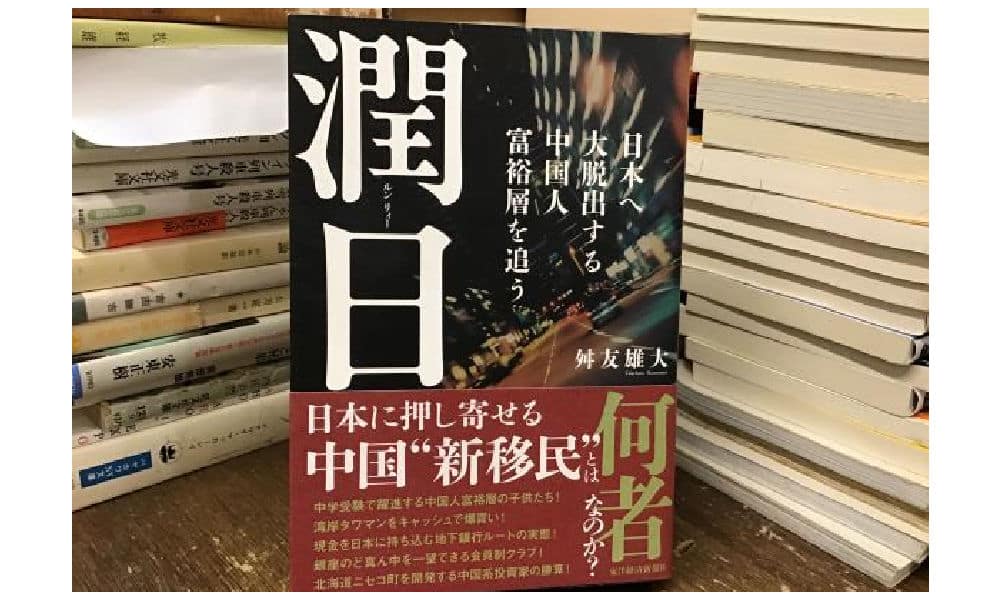

Why Chinese Elite Rùn to Japan (by ChinaTalk)

Over the past week, Japan has been trending every single day on Chinese social media in light of escalating bilateral tensions after Japanese PM Takaichi made remarks about Taiwan that China views as a direct military threat. The diplomatic freeze is triggering all kinds of trends, from rising anti-Japanese sentiment online and a ban on Japanese seafood imports to Chinese authorities warning citizens not to travel to Japan.

You’d think Chinese people would want to be anywhere but Japan right now — but the reality is far more nuanced.

In a recent feature in ChinaTalk, Jordan Schneider interviewed Japanese journalist & researcher Takehiro Masutomo (舛友雄大) who has just published a book about Japan’s new Chinese diaspora, explaining what draws Chinese dissidents, intellectuals, billionaires, and middle-class families to Tokyo.

The book is titled Run Ri: 潤日 Following the Footsteps of Elite Chinese Escaping to Japan (only available in Japanese and Traditional Chinese for now). (The word Rùn 润/潤, by the way, is Chinese online slang and meme expresses the desire to escape the country.)

A very interesting read on how Chinese communities are settling in Japan, a place they see as freer than Hong Kong and safer than the U.S., and one they’re surprisingly optimistic about — even more so than the Japanese themselves.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China Signals. For fast-moving trends and deeper dives, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you just so happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

A small housekeeping note:

This Eye on Digital China newsletter is co-published for subscribers on both Substack and the main site. If you’re registered on both platforms, you’ll receive duplicate emails — so if that bothers you, please pick your preferred platform and unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

“You think we’re scared of you? It’s not like we haven’t been to jail before.”

Published

7 months agoon

August 6, 2025

These days have been filled with tension and anger in the city of Jiangyou (江油市), Sichuan, after a rare, large-scale protest broke out following public outrage over a severe bullying incident and how it was handled.

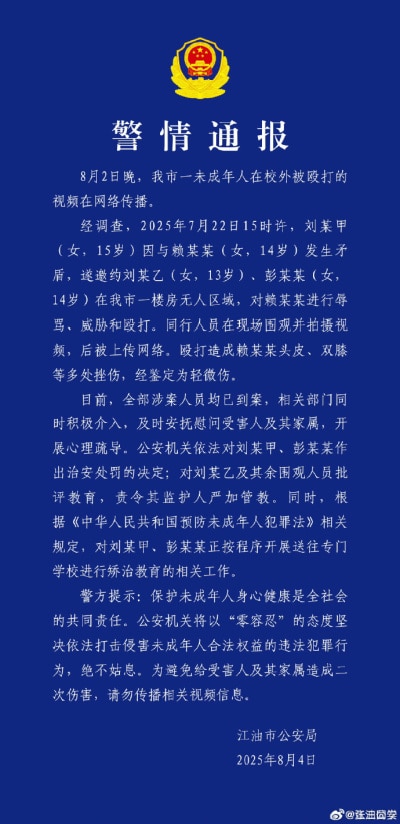

The bullying incident at the center of this story happened outside school premises in Mianyang on the afternoon of July 22. Footage of the assault, recorded by bystanders at the scene, began circulating widely online on August 2, sparking widespread outrage among concerned netizens, many of them worried parents.

The violent altercation involved three girls between the ages of 13 and 15 who ganged up on another minor, a 14-year-old girl named Lai (赖).

After Lai and a 15-year-old girl named Liu (刘) reportedly had a dispute, Liu gathered two of her friends—the 13-year-old also named Liu (刘) and a 14-year-old named Peng (彭)—to gang up on Lai.

The three underage girls lured Lai to an abandoned building, where they subjected her to hours of verbal and physical violence. The footage showed how they took turns in kicking, slapping, and pushing her.

At one point, after Lai said she would call the police, one of the bullies yelled: “You think we’re scared of you? It’s not like we haven’t been to jail before. I’ve been in more than ten times—it doesn’t even take 20 minutes to get out” (“你以为我们会怕你吗?又不是没进去过,我都进去十多次了,没二十分钟就出来了”).

That same night, the incident was reported to police. It took authorities until August 2 to bring in all involved parties for questioning, and a police report was issued on the morning of Monday, August 4.

Police report by Jiangyou Public Security Bureau, confirming the details of the incident and the (legal) consequences for the attackers.

Two of the girls (the 15- and 14-year-old) were given administrative penalties and will be sent to a specialized correctional school. The younger Liu and other bystanders were formally reprimanded.

“Parents Speak Out for the Bullied Girl”

The way the incident was handled—not just the relatively late official report, but mostly the perceived lenient punishment—triggered anger online.

Many people who had seen the video responded emotionally and felt that the underage girls should be stripped of their rights to take their exams, and that the bullying incident should forever haunt them in the same way it will undoubtedly haunt their victim.

Especially the phrase “It’s not like I haven’t been taken in [to jail] before” struck a chord, as it showed just how calculated the bullies were—and how, by counting on the leniency of the Chinese judicial system for minors, they made the system complicit in their determination to turn those hours into a living hell for Lai.

China has been dealing with an epidemic of school violence for years. In 2016, Chinese netizens were already urging authorities to address the problem of extreme bullying in schools, partly because minors under the age of 16 rarely face criminal punishment for their actions.

Since 2021, children between the ages of 12 and 14 can be held criminally responsible for extreme and cruel cases resulting in death or disability—but their legal prosecution must first be approved by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP).

It has not done much to stop the violence.

Discussions around extreme bullying like this have repeatedly flared up over the years, such as in 2020, when a 15-year-old schoolboy named Yuan (袁) in Shaanxi was fatally beaten and buried by a group of minors.

Last year, a young boy named Wang Ziyao (王子耀) was killed by three classmates after suffering years of bullying. His body was found in a greenhouse just 100 meters from the home of one of the suspects, and the case shocked and enraged local residents.

But the problem is widespread among girls, too.

In 2016, we already reported on how so-called ‘campus violence videos’ (校园暴力视频) had become a concerning trend. In these kinds of videos—often showing multiple bullies beating up a single victim on camera—it’s not uncommon to see girls as the aggressors.

Girls often form cliques to gang up on a victim to show that they are in control or to gain popularity. They also tend to be more inclined than boys to make cruel jokes or stage pranks meant to embarrass or humiliate their target. This may partly explain why there seem to be more campus violence videos on Chinese social media showing girls bullying girls than boys bullying boys.

In the case of Lai, she appears to have been particularly vulnerable. One of her relatives posted online that her mother is deaf and mute, and her father allegedly is disabled. This fact may have contributed to why Lai was repeatedly targeted and bullied by the same group of girls, who reportedly took away her phone and socially isolated her at school.

In response to the incident, netizens started posting the hashtag “Parents Speak Up for the Bullied Girl” (“#家长们为被霸凌女孩发声#), not only to support Lai and her family, but to demand harsher punishments for school bullies and for stricter crackdown on this nationwide problem.

From Online Anger to Offline Protest

While many people spoke out for Lai online, hundreds also wanted to show up for her in person.

On August 4, dozens of people gathered in front of the Jiangyou Municipal Government building (江油市人民政府) to demand justice and support Lai’s parents, who had come to express their grievances to the authorities—at one point even bowing to the ground in a plea for justice to be served for their daughter.

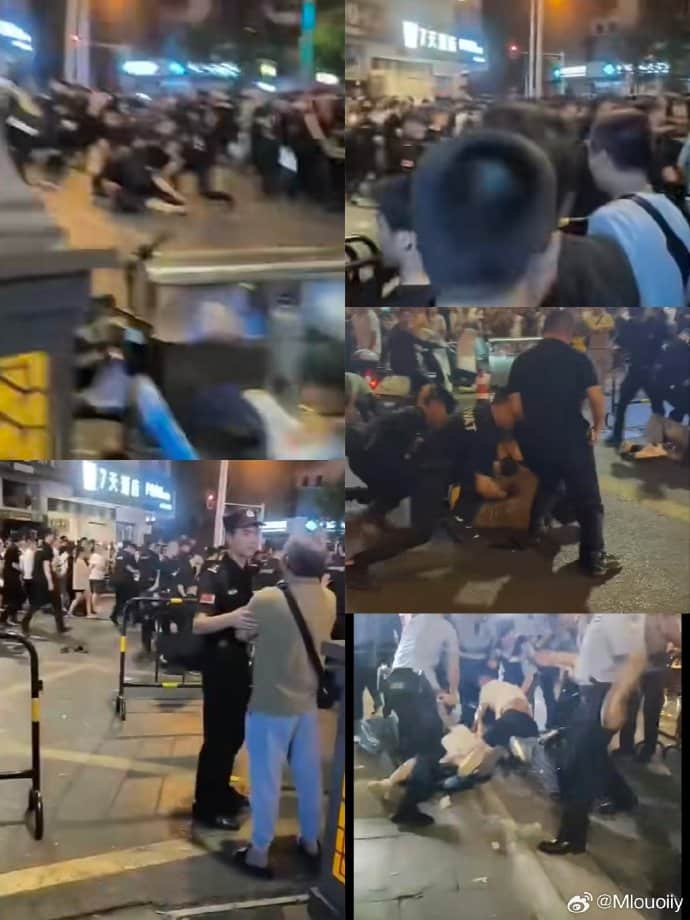

Footage and images circulating on social media showing the parents of Lai, the victim, bowing on the ground to demand justice from authorities.

As the crowd grew larger, tensions escalated, eventually leading to clashes between protesters and police.

The arrests at the scene did little to ease the situation. As night fell, the mood grew increasingly grim, and some protesters began throwing objects at the police.

Images of the protest, posted on Weibo.

Near the east section of Shixian Road (诗仙路东段), more people gathered. Hundreds of individuals filming and livestreaming captured footage of the police crackdown—officers beating protesters, dragging them away, and deploying pepper spray.

Netizens’ digital artwork about the bullying incident, the parents’ grievances, and the public protest and its crackdown in Jiangyou. Shared by 程Clarence.

Although the protests briefly gained traction on social media and became a trending topic on Weibo, the search term was soon removed from the platform’s trending list.

Lasting Mental Scars

On Tuesday, August 5, several topics related to the Jiangyou bullying incident began trending again on Chinese social media.

On the short video app Kuaishou, a collective demand for justice surged to the number one spot, under the tag “A large number of Jiangyou parents demand justice for the victim” (江油大批家长为受害学生讨公道).

As of now, none of the perpetrators’ families have come forward to apologize.

As for Lai—according to the latest reports, she did not suffer serious physical injuries from the bullying incident, but according to her own parents, the mental scars will last. She will need continued mental health support and counseling going forward.

Although many posts about the incident and the ensuing protests have been taken offline, ‘Jiangyou’s Bullying Incident’ has already become one more case in the growing list of brutal school bullying incidents that have surfaced on Chinese social media in recent years. The heat of local anger may fade over time, but the rising number of such cases continues to fuel public frustration nationwide—especially if local authorities fail to do more to address and prevent school bullying.

“Not being able to protect our children, that’s a disgrace to our schools and the police,” one commenter wrote: “I want to thank all those mothers who have raised their voices for the bullied child. Each of us must say no to bullies, and we must do all we can to stop them. I hope the lawmakers agree.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Spring Festival Trend Watch: Gala Highlights, Small-City Travel, and the Mazu Ritual Controversy

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West