Featured

Weibo Watch: Explosive Material

From nationalist influencers to the Handan murder case, Chinese social media was ablaze with more explosive topics this week than the Yanjiao blast alone.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #25

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Explosive material

◼︎ 2. What’s Been Trending – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What More to Know – Five bit-sized trends

◼︎ 4. What’s the Drama – Top TV to watch

◼︎ 5. What Lies Behind – Justice & social neglect in the Handan murder case

◼︎ 6. What’s Noteworthy – A 61-year-old twin toddler mom

◼︎ 7. What’s Popular – AI brings celebrities back from the dead

◼︎ 8. What’s Memorable – TikTok CEO hailed as “Asian hero”

◼︎ 9. Weibo Word of the Week – “Mellow People”

Dear Reader,

A devastating explosion in North China’s Yanjiao, claiming the lives of seven and injuring 27 others, has dominated Chinese social media discussions over the past few days. The incident not only raised questions about the cause of the blast but also sparked concerns about press freedom, as Chinese reporters were reportedly obstructed from their work at the scene. This fueled suspicions that local authorities might be withholding information from the public.

Despite its significant impact, the Yanjiao blast was not the most combustible topic on Chinese social media. Various other incidents and issues gained traction, largely driven by online nationalists.

The most eye-catching issue has been the so-called “battle of the two water bottles” (两瓶水之争), which emerged after the recent death of the much-beloved Chinese entrepreneur Zong Qinghou (宗庆后), founder of the Wahaha company known for its bottled water and beverages.

As detailed in our latest article here, a support campaign for the Wahaha brand morphed into a witch hunt against its major domestic competitor, Nongfu Spring. While Zong Qinghou was lauded as a patriotic entrepreneur, Nongfu Spring’s founder, billionaire Zhong Shanshan (钟睒睒), faced criticism for supposedly prioritizing profit over national interests.

From Weibo to Douyin and beyond, online influencers came up with all kinds of reasons why Nongfu Spring should be seen as an unpatriotic Chinese brand, from its product packaging containing Japanese elements to its water containing bugs.

One point of ongoing contention is the fact that Zhong’s son (his heir, Zhong Shuzi 钟墅子) holds American citizenship. This sparked anger among netizens who questioned Zhong’s allegiance to China. Numerous Douyin videos showed livestreamers pouring bottles of Nongfu Spring water down the drain, small shop owners recorded themselves removing Nongfu Spring products from store shelves, and overall sales plummeted. Because the issue was about affordable bottled water, participating in these kinds of ‘patriotic’ activities was relatively easy; consumer nationalism has never been cheaper.

When Chinese entrepreneur Li Guoqing (李国庆), co-founder of the e-commerce company Dangdang, defended Nongfu Spring and called for rationality, he too came under fire. Wasn’t his own son, Li Chengqing (李成青), an American citizen as well? Rumors about other Chinese entrepreneurs also started gaining traction.

While grassroots nationalist activities on Douyin and nationalist trends on Weibo aren’t new, the recent campaign against Nongfu Spring stands out as it targets a domestic company. Typically, Chinese online nationalism focuses on foreign brands, encouraging consumers to boycott foreign products and support domestic ones (buycott).

For instance, in 2021, Nike faced backlash and boycotts in China for its stance on Xinjiang cotton and a viral incident involving discrimination against a rural migrant worker by a Nike employee. The Chinese sportswear brand Erke indirectly profited from existing consumer sentiments over Nike, positioning itself as a patriotic alternative (read more here).

The current boycott of Nongfu Spring in favor of another ‘more patriotic’ Chinese brand represents a shift in online nationalism. It’s not top-down, it’s not state-led, and it’s not necessarily driven by political ideology. On the one hand, this is a sign of Chinese economic growth as domestic brands and companies are no longer considered the ‘underdog’ in a market dominated by bigger foreign brands. It reflects Chinese consumers’ confidence in made-in-China brands and a desire for them to embody their national identity.

On the other hand, this movement sheds light on the dynamics of contemporary Chinese social media and “the business of nationalism” (also described by Zhang & Ma, 2023, 899). Various actors in the Chinese digital ecosystem profit from the commodification of nationalist content on platforms like Weibo and Douyin, where patriotism and aggressive nationalism are amplified for commercial gain (Liao & Xia 2023, 1536).

Influencers, too, capitalize on patriotic narratives to garner attention, often at the expense of balanced discourse, as the algorithm pushes aggressively nationalist discourses to the forefront (Schneider 2022, 277).

Regular users of these platforms find themselves navigating an environment where extreme views dominate, perpetuating a cycle of nationalism. With a click, post, or video, they can be part of an online nationalist movement that’s driven by hype, not necessarily representative of nationalism on the ground, and sometimes more fleeting than a fast food trend — you could call it nationalist clicktivism.

All of this forms a toxic cocktail that can flare up and become explosive from time to time. But, this too shall pass. Some smart Chinese restaurant owners know that as well. They have started buying Nongfu Spring water in bulk. The price has never been lower, and the water will still be sellable by the time the storm has calmed. For them, too, nationalism has never been cheaper.

Best,

Manya (@manyapan)

References:

Liao, Sara and Grace Xia. 2023. “Consumer Nationalism in Digital Space: A Case-Study of the 2017 Anti-Lotte Boycott in China”. Convergence, 29(6), 1535-1554.

Schneider, Florian. 2022. “Emergent Nationalism in China’s Sociotechnical Networks: How Technological Affordance and Complexity Amplify Digital Nationalism.” Nations & Nationalism 28(1): 267-285.

Zhang, Chi and Yiben Ma. 2023. “Invented Borders: The Tension Between Grassroots Patriotism and State-Led Campaigns in China.” Journal of Contemporary China, 32(144), 897-913.

What’s Been Trending

1: Wahaha vs Nongfu Spring | It’s the big topic that’s been fermenting online for some time now: Nongfu and the online nationalists. The praise for one Chinese domestic water bottle brand, Wahaha, sparked online animosity toward the other, Nongfu Spring, after the death of Wahaha founder Zong Qinghou. While Wahaha is seen as a patriotic, proudly made-in-China brand, big competitor Nongfu Spring and its founder Zhong Shanshan are under attack for allegedly being profit-driven and disloyal to China. The online anti-Nongfu campaign has even led to people pouring out their Nongfu Spring water bottles. Read all about it here👇🏼

2: Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag | A hashtag promoted by Party newspaper People’s Daily recently became top trending: “Wang Yi Says the Next China Will Still Be China” (#王毅说下一个中国还是中国#). The hashtag refers to statements made by China’s Foreign Minister, Wang Yi (王毅), during a press conference held alongside the Second Session of the 14th National People’s Congress. After Wang Yi’s remarks, the sentence ‘the next China will still be China’ has now solidified its place as a new catchphrase in the Communist Party jargon. But what does it actually mean?

3: Online Tributes to Toriyama | Chinese fans have been mourning the death of Japanese manga artist and character creator Akira Toriyama. On March 8, his production company confirmed that the 68-year-old artist passed away due to acute subdural hematoma. On Weibo, a hashtag related to his passing became trending as netizens shared their memories and appreciation for Toriyama’s work, as well as creating fan art in his honor (also see this tweet). Chinese readers form the largest fan community for Japanese comics and anime, and for many Chinese, the influential creations of Akira Toriyama, like “Dr. Slump” and particularly “Dragon Ball,” are cherished as part of their childhood or teenage memories.

What More to Know

◼︎ 🏛️ Boy Murdered by Classmates | A case in which a young boy from Feixiang county in Handan, Hebei, was murdered by three classmates has recently shocked the nation. The young boy, Wang Ziyao (王子耀), had suffered years of bullying before his three classmates, all 13 years old, brutally killed him. Wang had been missing for one day before his body was discovered buried in a greenhouse in a field nearby the home of one of the suspects. While the three suspects have now been detained, netizens and legal scholars are discussing whether the case could be handled by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP). Since an amendment to China’s Criminal Law in 2021, children between the ages of 12-14 can be held criminally responsible for extreme and cruel cases resulting in death or severe disability, if approved for prosecution by the SPP. A chilling video showing the palpable shock in Handan after Wang’s body was recovered by authorities also made its rounds online, see here. (Various related Weibo hashtags, including “#13-Year-Old Middle School Student Killed By Classmate, Three Arrested” #13岁初中生被同学杀害三人被刑拘#, 150 million views; “#CNR Discusses Case in Which Junior High School Student Was Killed and Buried by 3 Classmates #央广网评初中生被3名同学杀害掩埋#, 200 million views).

◼︎ ♪ U.S. TikTok Ban | Besides the battle over water, the battle over TikTok has also generated hashtags and discussions on Chinese social media after the US House of Representatives passed a bill that could lead to an American TikTok ban if parent company Bytedance does not sell the app. Security concerns surrounding TikTok’s ownership by a Chinese company and its access to American data have existed ever since the app became popular in the US, where it now has over 170 million users. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin denounced the bill, suggesting it was unfair for US to cite security reasons to “arbitrarily” suppress TikTok. Many social media commenters agree with this stance, suggesting the app is solely targeted because of its Chinese parent company, unrelated to actual security risks. The Singaporean TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew (周受资) is expected to pay US legislators a visit in the coming days to fight against the ban, which is something many netizens are looking forward to (Shou Zi Chew is very popular on Weibo). (Hashtag: “American House of Representatives Passes Tiktok Bill” #美众议院通过tiktok法案#, 160 million views; “#TikTok Strikes Back” #TikTok开始反击#, 140 million views).

◼︎ 🛒 Livestreaming Chaos | Many different topics popped up during this year’s 3.15 Consumer Day and the two-hour annual Chinese Consumer Day Gala television show, which is all about raising awareness of consumer rights. One hot topic within this context is China’s “chaos of live-streaming e-commerce” (直播带货乱象). People’s Daily reported that in 2023 alone, more than half (56.1%) of the complaints received at the “12315” consumer hotline were related to online shopping, primarily through livestreaming. Over the span of five years, complaints regarding live e-commerce have surged by 47 times. The primary concerns revolve around after-sales service problems, such as the difficulty in returning items, and quality issues, wherein products showcased in livestreams differ from what customers actually receive. (Hashtag “#Most After-Sales Complaints About Livestreaming Ecommerce” #售后服务直播带货投诉排名第一#, 34.8 million views).

◼︎ 🇬🇧 Where’s Kate? | Speculation and controversy surrounding the whereabouts of the Princess of Wales, Kate Middleton, have also surfaced on Weibo, where discussions about the UK royals have been trending in recent days. Worldwide, rumors about her condition emerged following her absence from any official public appearances since January 16, when she underwent abdominal surgery. The situation intensified when a photo of the Princess and her children, shared on Mother’s Day, raised suspicions of editing and photoshopping. Although Kate took responsibility for altering the image herself, the internet erupted with various theories about her situation, ranging from serious illness to marital issues or even another pregnancy. Some commenters suggest the Chinese interest in the issue is because “we love to watch palace drama.” (Hashtag “Where is Princess Kate?” #凯特王妃去哪了#, 40 million views; “Rumors of Princess Kate Missing Stirs Up UK” #凯特王妃失踪传闻搅动英国#, 43 million views).

◼︎ 🖋️ Chinese Author Mo Yan Under Attack | Another story that has been circulating online for some time involves Chinese blogger Wu Wanzheng (@说真话的毛星火) initiating a lawsuit against the renowned Chinese author and Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan (莫言). Wu accuses Mo Yan of distorting history and tarnishing the legacy of the Communist Party in his 1986 novel Red Sorghum (红高粱). The well-known Chinese internet commentator Hu Xijin recently came to Mo Yan’s defense, which actually increased media attention for the case. Although the initial attempt to sue Mo Yan was rejected by a Beijing court, Wu allegedly intends to persist with his mission. Opinions on the matter are divided: while some believe Wu is within his rights to pursue legal action against Mo Yan, others view the entire affair as a sensationalist grab for attention. Meanwhile, various articles and hashtags about the case have been taken offline (Weibo hashtag “Mo Yan Sued” #莫言被起诉#, 1.8 million views; “Hu Xijin: Person Suing Mo Yan Is Taking Words Out of Context” #胡锡进称起诉莫言者是在扣帽子断章取义#, 29 million clicks).

What’s the Drama

The Chinese historical drama “In Blossom” (花间令) currently ranks number one on Weibo. It premiered on the streaming platform Youku on March 15. The costume drama revolves around the story of the handsome Pan Yue (Liu Xueyi 刘学义), who marries Yang Caiwei (played by Ju Jingyi 鞠婧祎). She is murdered on the night of their wedding, and he is the prime suspect. But Yang Caiwei miraculously returns from the dead to uncover the truth.

▶️ This drama was directed by Zhong Qing (钟青), who is best known for directing suspenseful and romantic dramas.

▶️ The Weibo hashtag about “In Blossom” has received over two billion views already (#花间令#).

▶️ The first day after “In Blossom” was released, it already broke some viewing records; on March 16, 13.6% of Youku audiences had watched the drama, making it the first drama this year to become so popular within such a short timeframe.

You can watch In Blossom with English subtitles via YouTube here.

What Lies Behind

With emotions running high on social media, many are eager to learn about the fate awaiting the three young perpetrators in the trending case of the bullied boy from Handan, Hebei, who was killed and buried by his classmates. Online discussions mostly revolve around the legal and social aspects of this case.

There’s widespread frustration over the possibility of lenient punishment for the 13-year-old suspects due to their age. As China still has capital punishment, some people are even calling for execution once they turn 18.

These sentiments do not come out of the blue. In recent years, China has seen a rise in crimes, including murders, committed by minors. Many people are worried that without properly addressing the bullying problems that are prevalent among young people, the country will only see an increase in minors committing serious crimes like assault, rape and murder.

Online discussions show that people are reluctant to accept the “Law on the Protection of Minors” which recognizes the limited understanding young offenders may have of their own actions’ gravity and consequences. Chinese criminal psychologist and youth education expert Mei Jinli (李玫瑾) suggests that families or legal guardians should bear part of the responsibility exempted from the child due to their age.

Another issue that has caught people’s attention in this case is that all suspects and the victim are so-called “left-behind children” (留守儿童). With over 295 million Chinese rural migrant workers leaving their hometowns to find jobs in the city, many find themselves unable to bring their children due to the household registration system in China. Instead, they leave their children behind with grandparents or family.

Chinese experts and charities have been raising awareness of psychological trauma among these children – there are some 67 million of them – and are calling for changes in the household registration system so that migrant workers can bring their children with them instead of leaving them to fend for themselves.

The comments surrounding this case highlight how deeply it resonates with many. One commenter said he was a left-behind child himself, and when he saw the words “left-behind children” and “raised by grandparents” in the news, he couldn’t help but burst into tears.

What’s Noteworthy

During the Two Sessions, China’s annual parliamentary meetings, numerous proposals and “suggestions” (建议) put forth by National People’s Congress delegates became trending topics on Chinese social media. While a proposal in 2020 aimed to prohibit single women from freezing their eggs to encourage them to “marry and reproduce at the appropriate age,” a recent proposal suggests the opposite approach to address China’s declining birth rates: improving fertility treatment options for older Chinese women to facilitate childbearing for older parents.

Uncoincidentally, during the same week, a Chinese media outlet shared the story of a 61-year-old twin mom recounting her experience of ‘late parenthood.’ Having lost her 26-year-old son in a car accident in 2014, Zhang Yumei attempted to conceive for seven years and eventually welcomed healthy twin daughters in 2021, at the age of 58. In an interview with Chinese media, the senior citizen expressed that her two children have given her “the courage to continue living.” The story garnered significant attention on Chinese social media, with many sympathizing with Zhang Yumei. However, some netizens speculated whether authorities would now begin encouraging elderly women to use donated eggs for childbirth.

Read more about other proposals made during the Two Session in our article here.

What’s Popular

This video shows Chinese singer & actor Qiao Renliang (乔任梁) in 2024. He actually died in 2016.

Using AI tools, Chinese social media users are reviving deceased celebrities like Qiao, Coco Lee, or Godfrey Gao. By using old videos and images, artificial intelligence digitally recreates them, bringing them back to life in online videos. A recent example sparking controversy is the video featuring Chinese singer and actor Kimi Qiao Renliang (乔任梁), who took his own life in 2016 at the age of 28. In the AI-generated video, Qiao states, “Actually, I never really left…”

His parents are unsettled by the video. Qiao’s father is now urging netizens to delete these videos of his son. He says they were created without permission and violate his son’s portrait rights. It has sparked some much-needed discussion on the legal and ethical issues surrounding so-called ‘AI resurrection’ (AI复活).

In an online poll conducted by Sina Hotspot (新浪热点) among 80,000 netizens on Weibo, a significant majority of respondents, over 66,000, expressed that recreating deceased celebrities is unacceptable. Only 2,100 people said they see practice as a nice way to remember celebrities who’ve passed.

What’s Memorable

This pick from our archive takes us back to when Shou Zi Chew (周受资, Zhou Shouzi), the Singaporean CEO of TikTok, appeared before the House Energy and Commerce Committee in the United States, facing a four-and-a-half-hour hearing over data security and harmful content on the TikTok app. Some bloggers and commenters noted how Chew fits the supposed idea of a ‘perfect Asian’ by staying calm despite unreasonable allegations and emphasizing business interests over culture. The so-called “Mr. Perfect In the Eye of the Storm” is going back to defend TikTok this week, so we can expect him to receive a lot of support from Chinese netizens again. Read more about it here 👇

Weibo Word of the Week

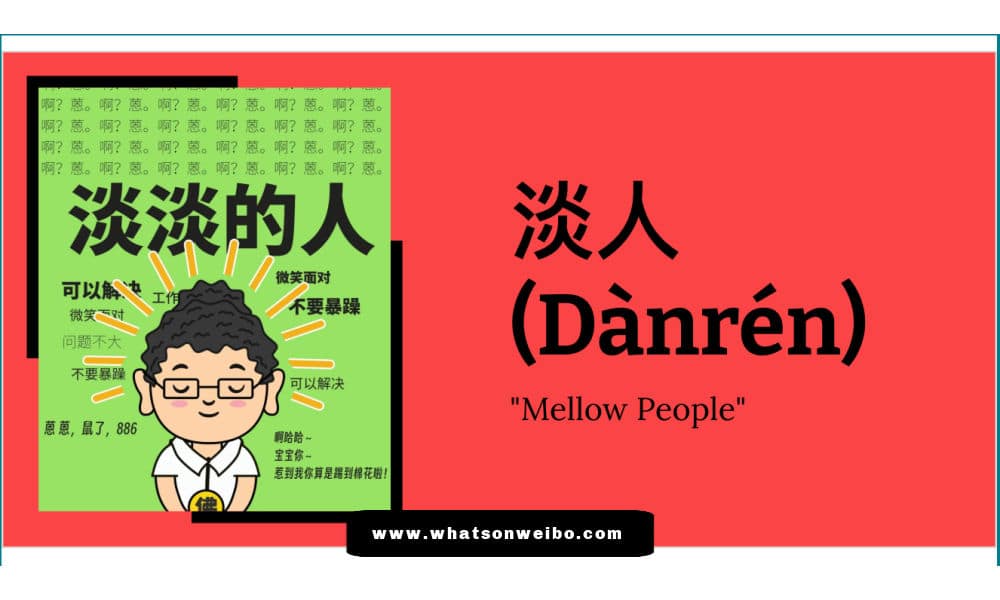

“Mellow People” | Our Weibo Word of the Week is “Mellow People” or “Mellow Person” (dàn rén 淡人), a term that’s popped up recently to self-describe the mental state of young people in China today.

The word dàn 淡, which I’ve translated as ‘mellow’ in this context, can mean numerous things in China: it’s light, calm, indifferent, pale, or even trivial. Being a dàn individual, a dànrén 淡人, has recently come to be used by young people to describe themselves and how they experience life. They might want to quit their crappy job, but it generates money so it’s okay. They have to commute for hours every day, but the rent is cheaper so it’s okay. They are being forced to go on blind dates by their parents and actually don’t want to, but they don’t have the energy to refuse so it’s okay.

Being this ‘mellow’ or ‘unperturbed’ means being indifferent in a calm and light way. Not unlike previous Chinese popular expressions such as “lying flat” (躺平) and being “Buddha-like” (佛系) (read here), it’s a way to cope with the challenges and pressures faced by Chinese young people today, but it’s a bit more positive than being completely passive (lying flat): it’s a passive acceptance of life as it is, embracing dull daily routines or competitive work environments without resistance. The art of being or becoming a dàn rén is also referred to as 淡人学 dànrén xué, which could be translated as ‘Mellowism’ or, perhaps even better, ‘Unperturbabilism.’

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chinese New Year

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

Watch the CGM Spring Festival Gala with us. It’s that special annual evening show that captures millions of viewers on the night of the Chinese New Year. Loved by many, hated by some, it always generates social media buzz.

Published

3 days agoon

February 16, 2026

Support us and get future newsletters in your inbox by subscribing on the main site or Substack (same content), or buy us a cup of tea 🍵

Watch the CGM Spring Festival Gala with us. It’s that special annual evening show that captures millions of viewers on the night of the Chinese New Year. Loved by many, hated by some, it always generates social media buzz. We’ll bring you the ins & outs of the 2026 Gala and its social media frenzy, with updates before, during, and after the show.

It is time again for the China Media Group Spring Festival gala – better known as the ‘Chunwan’ (春晚) – one of China’s most significant televised cultural events of the year, organized and produced by the state-run CCTV since 1983 and broadcast across dozens of channels, watched by millions.

What can we expect a typical Chunwan to look like? The programme usually runs for about four hours, from 20:00 China Standard Time to a little past midnight, and features around 30 acts: acrobatics, singing, dance, comic sketches (xiaopin 小品), crosstalk (xiangsheng 相声), magic, Peking Opera, public service segments, and tributes to national heroes. This year, however, some things will be different — more on that soon.

Liveblogging the show has become something of a personal tradition. You can explore more of my Gala coverage on the website here, spanning the past ten years, during which I liveblogged eight editions.

Tonight, I’m watching the Gala together with Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang, so follow along in the liveblog below. Keep the page open and you should hear a ping when new updates arrive.

Update: This liveblog is now closed. You can still read all updates below, sorted from oldest to newest.

Chapter Dive

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

Han Futao’s explosive report on fake patients and systemic abuse has triggered a heated online debate over hospital malpractices, the fragility of the welfare system, and the vital role of investigative reporting.

Published

3 days agoon

February 15, 2026By

Ruixin Zhang

In early February, as China settled into the quiet anticipation of the Chinese New Year, one of the country’s leading investigative journalists, Han Futao (韩福涛), dropped a bombshell report that sent shockwaves of anger across the country.

Han Futao is known for breaking massive scandals. In 2024, he exposed how tank trucks that delivered chemical products also transported cooking oil, without being cleaned. That food safety scandal sparked waves of outrage and prompted a high-level official investigation, leading to criminal charges for those involved.

In his latest explosive report, published by Beijing News (新京报), Han has turned his lens to malpractice in China’s hospital sector. His investigation led him to Xiangyang, in Hubei province, a city with more than twenty psychiatric hospitals, cropping up on every corner “like beef noodle shops” over recent years.

Recruiting Patients

Han found that multiple private psychiatric hospitals lure people in under the guise of free care, promising treatment for little or no cost, along with medication and daily expenses. Some even dispatched staff to rural villages to recruit “patients.”

Troubled by the unusual marketing procedures of these psychiatric hospitals, Han went undercover at several facilities as a caregiver, and sometimes posing as a patient’s family member, only to expose a disturbing reality.

Except for a handful of genuine patients, these hospitals were filled with healthy people who actually received no treatment. Many were elderly citizens swayed by the promise of “free care,” checking in with the hope of finding a free retirement home.

When Han, posing as a patient’s family member, spoke to a hospital manager at Xiangyang Yangyiguang Psychiatric Hospital (襄阳阳一光精神病医院), the director enthusiastically pitched their “free hospitalization” by saying medical fees were completely waived and promising the potential patient a great stay: “Lots of patients stay here for years and don’t even go home for Chinese New Year!”

Meanwhile, the hospitals’ own staff, including caregivers, nurses, and security guards, were also officially registered as patients, complete with admission and hospitalization procedures.

The motive was simple: insurance fraud (骗保 piànbǎo). In China, even after state medical insurance covers part of psychiatric care costs, patients are typically still responsible for a co-pay. These hospitals, both in Xiangyang and in the city of Yichang, exploited the financial vulnerability of those unwilling or unable to pay, using the lure of free accommodation to attract the misinformed. Once admitted, the hospitals used their identities to fabricate medical records and bill the state for non-existent treatments.

According to internal billing records, medication accounted for only a small fraction of patients’ costs. The bulk of the charges came from psychotherapy and behavioral correction therapy, which often leave little material trace and, in these cases, were never actually provided. Many of these hospitals even lacked basic medical equipment and qualified personnel.

Staff were essentially manufacturing invoices, generating around 4,000 yuan (US$580) in fraudulent charges per patient each month, with most funds diverted from the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA).

With each patient yielding thousands of yuan, profitability became a numbers game: the more bodies in beds, the higher the revenue. This perverse incentive gave rise to a specialized workforce of marketers who recruited ordinary people from rural areas, developing sales pitches and establishing referral-based kickback chains, offering bonuses of 400 ($58) to 1,000 yuan ($145) for every new “patient” successfully brought in.

To stay under the radar, hospitals periodically discharged patients on paper to avoid scrutiny from insurance auditors, only to readmit them immediately, or never actually let them leave at all. One story involved a patient who was discharged seven times, each time being readmitted on the same day he was “discharged.”

Day after day, the national medical insurance fund, built on the collective contributions and trust of the entire population, was drained through these calculated deceptions.

From Patients to Prisoners

Han uncovered more. Even more harrowing than the scale of the medical insurance fraud was the condition of those trapped inside. To maximize profit margins, these hospitals slashed costs to the bone. Living conditions were terrible: wards overcrowded, beds crammed side-by-side, and daily activities and food substandard at best.

The hospitals treated their patients more like profit-generating assets than human beings. Patients were subjected to a strict regime: they were forced to follow rigid schedules, restricted to designated zones, and faced physical violence if they did not comply.

During Han’s undercover research, he witnessed the horrific sight of patients being tied to a bed for not following orders, with some patients allegedly being restrained for up to three days and three nights.

Photo by Han Futao, in Beijing News, showing a hall filled with beds at the Yichang Yiling Kangning Psychiatric Hospital, where more than 160 people were housed in just one ward. The lower photo, also by Han Futao, shows elderly “patients” kept in their wheelchairs all day at Xiangyang Hong’an Psychiatric Hospital.

Some patients, despite technically being the ones receiving care, were forced to perform manual labor for the staff. They scrubbed pots, cleaned wards, mopped latrines, and moved supplies. Others even had to take on nursing tasks for fellow patients, such as feeding, bathing, and changing clothes, all in exchange for a few cents to buy a cigarette. Their personal freedom and quality of life were virtually non-existent.

Escape was also difficult. The hospitals had no intention of releasing their cash cows. Rarely was a patient discharged on the scheduled date. To ensure long-term residency, many hospitals confiscated patients’ phones and cut off contact with their families.

Some individuals spent nearly ten years in these prison-like conditions; some even died there. Meanwhile, those truly suffering from mental illness received no real treatment, often seeing their condition worsen or developing deep-seated trauma toward psychiatric care.

Fragile Public Trust in Welfare-Related Institutions

In China, there is a common belief that if you spot one cockroach in the room, there are already a hundred more hiding. As the story has gone viral over the past two weeks, netizens pointed out that Xiangyang and Yichang were likely not the only cities using such predatory tactics to cannibalize the national treasury. Han’s investigation struck a deeper nerve, and public anxiety over the security of social insurance once again bubbled to the surface.

China’s national health insurance is a cornerstone of the broader social insurance system and a vital part of life for nearly every citizen. It is generally divided into two categories: Employee Medical Insurance and Resident Medical Insurance. Employers are legally, at least in theory, required to contribute to the employee scheme, typically 6% to 9% of a worker’s salary. Non-employees, such as farmers, students, and freelancers, usually pay for Resident Insurance out of pocket, currently costing around 400 yuan ($58) annually. Under the employee scheme, inpatient reimbursement rates are roughly 80% to 85%; after approximately 25 years of contributions, members enjoy lifelong coverage without further payments. The Resident Insurance, however, offers significantly lower protection.

This system was designed as a fundamental safety net to alleviate the fear of falling into poverty due to illness or being left destitute in old age. For young Chinese job seekers, whether a company pays into social security used to be a non-negotiable criterion. However, as scandals shaking the foundation of this system have become more frequent, the mindset of the youth is shifting: Is it even worth paying into anymore?

Recent years have seen a steady stream of corruption scandals involving the embezzlement of social security funds.

Despite the authorities’ firm stance and high-profile punishments, 2025 was still marked by reports of officials — including the insurance bureau’s finance head — misappropriating funds to play the stock market. A June 2025 report even alleged that 40.6 billion yuan (US$5.8 billion) in national pension funds had been misappropriated or embezzled by local governments.

In one surreal case from Shanxi, a CDC employee’s records were doctored 14 times to create an absurd history of “starting work at age 1 and retiring at 22,” allowing them to pocket 690,000 yuan ($100,000) in pension while still drawing a salary at a new job.

These stories exposing large-scale abuse of the medical insurance system, combined with the extension of the minimum contribution period for retirement from 15 to 20 years amid a slowing job market and a gradually rising retirement age, are leading netizens to question the necessity of paying into the system. This is reflected in comments such as:

-“First it was 20 years, then 25, then 30. They move the goalposts whenever they want, but the benefits never improve.”

-“I won’t buy anything beyond the bare minimum resident insurance; who knows if there will even be a payout in the future?”

-“With a deficit this large, whether we’ll ever see that money is a huge question mark.”

-“I’m not even sure I’ll live to see 65 anyway.”

Echoes of the Cuckoo’s Nest

In response to Han’s latest exposure, local authorities immediately launched investigations, and state-run media outlets issued sharp criticism. By now, fourteen hospital executives have been criminally detained on suspicion of fraud.

Although the official report, published on the night of February 13, acknowledged that there was widespread medical fraud, with patients remaining hospitalized after recovery or empty beds being registered without any patients there, it said no evidence was found that people without mental disorders were admitted, which was one major finding of Han’s undercover operation.

This led to new questions, because how could fraud, abuse, fake discharges, and official corruption be acknowledged while denying the central allegation: that healthy people were being locked up? And how could people prove they were not mentally ill, while being a patient inside a psychiatric hospital?

Political & social commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) wrote on Weibo that, while he applauded Han and his team for exposing the mismanagement at psychiatric hospitals in Hubei, he also saw the report’s conclusions about the patients as a reminder that journalists should exercise caution when making accusations. Some sarcastic commenters suggested that perhaps Han had not sacrificed enough and should have admitted himself as a patient instead.

And so, in a way, the debate has now slowly also shifted – from the initial shock over Han’s report, to the anger and distrust surrounding state institutions and social security abuse, to the role of investigative journalism in China today. “He’s a hero,” some commenters said about Han.

In the end, the entire story is so absurd that some commentators have drawn parallels to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (飞越疯人院), where Randle P. McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) fakes insanity to serve his sentence in a mental hospital instead of a prison work farm, only to find out that the endless chain of control and abuse at the psych ward is much more brutal than a prison cell.

The question inescapably becomes who the sane ones actually are.

Meanwhile, the scandal shows that public anxiety about the future and distrust of state institutions tend to rise quickly and deepen slowly with each new controversy. As trust in the national welfare system appears fragile, one sentiment persists: that there is far more to uncover, and that there are far too few Han Futaos to do it.

By Ruixin Zhang

With additional reporting by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West