China and Covid19

Resisting the Rat Race: From China’s Buddhist Youth to Lying Flat Movement

Supporters of China’s ‘lying flat’ movement says it is a form of collective emotional catharsis, but state media suggest it goes against the Chinese Dream.

Published

2 years agoon

‘Lying flat’, tǎng píng , became a hot social trend in China in 2021. It received a lot of attention since, with some media calling it an “act of resistance.” Recently, especially in the light of China’s fight against Covid-19, there seems to be more resistance against this movement, with official media claiming that China’s dedicated, patriotic youth should never choose to ‘lie flat.’

This article was commissioned and produced by the Goethe-Institut for the Standstill Magazine: www.goethe.de/stillstand“. For a German-language version of this article, please see “Keine Lust auf das Hamsterrad.”

In March of 2022, the term tǎng píng (躺平), ‘lying flat’, was trending on Chinese social media. Since the word became popular online and was selected as a 2021 buzzword of the year, it has become part of everyday internet language in China and often pops up in online discussions.

By now, ‘lying flat’ has been adapted by Chinese state media and is painted in a different light from how it initially emerged when it was used by young people to address their views on life.

What actually is ‘lying flat’? How has its meaning shifted, and what does it have to do with Covid19, a ‘Buddhist-like mindset’, and the problem of so-called ‘involution’? Here, we will explore these terms and zoom in on discussions surrounding China’s ‘Lying Flat’ movement.

“Buddhist Youth” and Other Tribes

Every year, the Chinese language magazine Yǎo Wén Jiáo Zì (咬文嚼字) selects the most popular new words and expressions that often reveal trends among young people and also shed light on China’s rapidly changing society.

One of the Chinese top ‘buzzwords’ of 2018 was fó xì (佛系), a term from Japanese that started to be used in China to describe a “Buddha-like mindset.” In Japan, the term emerged in the media in 2014 to describe a specific type of male, “Buddhist men” (佛系男子), who are solely focused on their own hobbies and interests and self-indulgence without wasting any time on dating or love. The term also became popular among Chinese web users in late 2017 after a viral essay1 by WeChat account Xin Shixiang (新世相) used it to describe the lifestyle and mindset of many Chinese born in the 1990s (Sun 2017; Wu & Ren 2018, 15).

In the Chinese context, fó xì youth (佛系青年) mainly refers to people in their twenties or thirties who are pursuing a peaceful lifestyle in a fast-paced society. Despite being labeled as a “Buddhist mindset,” the term does not have a lot to do with Buddhist traditions. Instead, it refers to a laissez-faire attitude where one does not take on any responsibility and just goes ‘with the flow’ in order not to waste any time on trivial things.

According to an analysis by Hongjuan Wu and Ren Ying (2018), the term is not a ‘positive’ one per se, but more one of anxiety and negativity where people are merely divulging in their own interests due to a lack of motivation and loss of willingness to interact with others and function in a highly competitive environment. The authors claim that China’s “Buddhist youth” are looking for ways to escape the pressures they face in an everyday life where so much is expected of them, while they still struggle to pay for housing, medical care, and education – even if they work very hard.

Buddhist youth adheres to three principles: everything’s alright, it’s all ok, it doesn’t matter (image via QQ.com).

Instead of joining the urban struggle and striving for a better everything (better housing, better jobs, better education), they just accept their reality as it comes: it doesn’t matter if you win, if doesn’t matter if you lose, it doesn’t matter if you’re happy, it doesn’t matter if you’re sad. The 2018 popularity of the somewhat self-deprecating term ‘Buddhist youth’ reflects a collective feeling of a certain helplessness among China’s post-90 generation urban dwellers who are trying to take back control by letting go.

The internet age has made these kinds of social sentiments and movements more visible than ever before, and some buzzwords spread so rapidly that they can turn into subcultures within a matter of weeks. Some specific terms and memes resonate with millions of people who identify with them, and they are also a way for people to connect to each other and create a sense of belonging. That sense of having some shared identity is underlined by the fact that these terms are often described as modern-day ‘tribes’ or ‘clans’ (族).

When the Chinese housing market experienced surging house prices over a decade ago, the term ‘Ant tribe’ (蚁族) first saw the light – a neologism to describe a huge group of low-income, urban graduates who are hoping to find a job and settle down but end up living in poorer, crowded communities on the outskirts of the city where the rent is cheap (Michels 2014, 31).

Similarly, the same period saw the emergence of the ‘Moonlight tribe’ (月光族), those younger workers who always spend their entire monthly salary on material things and having fun, enjoying the moment and not worrying about the future. You also had the ‘Flea tribe’ (跳蚤族) (job hoppers who are always looking for the next opportunity), the ‘Latte tribe’ (urban dwellers doing things at their own pace), and many more different subcultures or social buzzwords.

“Out of money” – the ‘Moonlight clan’ referred to those young people would immediately spend all of their wages, leaving them completely broke before the end of the month (image via Doutu).

There was also a major group of Chinese internet users who started labeling themselves as diǎosī (屌丝), basically meaning “losers”, using self-mockery and satire as a form of humoristic self-medication to deal with the hardships of everyday life and growing social inequality in contemporary China. The term diaosi became one of the most popular Internet memes of 2012, signaling a growing disillusionment among (low-income) Chinese youths about being able to climb the social ladder (Szablewicz 2014, 259 -260).

Involution and Lying Flat

Over the past decade, the Chinese internet has seen more and more memes and buzzwords relating to the ‘rat race’ of modern-day China. Two of the most prominent one are ‘involution’ and ‘lying flat,’ which were also both selected for the annual buzzword lists of Yǎo Wén Jiáo Zì for 2020 and 2021 respectively.

The concept of nèijuǎn (内卷), “involution,” describes the economic situation in which as the population grows, per capita wealth decreases. The term originally comes from a 1963 work by the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz describing the dynamics of an Indonesian fast-growing population caught up in high-labor intensive wet-rice cultivation without making real progress (Koetse 2021).

The term ‘involution’ comes from this book by Geertz, published in 1963.

In the Chinese context, the term has come to be used to represent the competitive circumstances in academic and professional settings where individuals are compelled to overwork because of the standard raised by their peers who appear to be even more hardworking. In a work and education environment where people continuously work harder and longer, increased work efforts become the new normal without becoming more rewarding.

One scene from the popular Chinese television drama A Love for Dilemma went trending on social media in 2021 because many netizens thought it perfectly captured the essence of ‘involution.’ In the scene, two fathers discuss the Chinese education system, comparing it to a crowded movie theater where everyone is trying to watch the show together, until one person stands up to see more, forcing others behind them to also stand up to be able to see the screen. Then people stand on their seats, or even bring in ladders, so that they can rise above the rest. Consequently, the others are also scrambling to get higher up, but in the end, nobody is comfortable. The entire audience is stressed out and they all experience difficulties in watching the movie, while they could have just comfortably watched together if they would have remained in their seats (Koetse 2021).

One photo that has come to represent the concept of involution shows the ‘Tsinghua Volution King’ (清华卷王), which is the nickname of a student who is cycling at the campus of Tsinghua, one of China’s top universities, while simultaneously working on his laptop – not wasting a single moment to stay ahead of his peers.

The Tsinghua Volution King (image via QQ.com)

The generation that is most affected by a sense of being stuck in a ‘rat race’ of socioeconomic stagnation is the post-90 generation. In 2020, a record-high of 8.74 million university graduates entered the Chinese job market while many industries recruited fewer people than before in an employment market that was already competitive before the pandemic. These young adults end up in a pressure cooker where they are stressed when they do not have that top job, afraid of missing the train, and where they are also stressed when they do have that top job, afraid of falling off the train (Koetse 2021).

Closely related to the concept of involution, offering an alternative to the rat race, is the social trend of ‘Lying Flat’ (躺平), also known as ‘Lying Flatism’ (躺平主义, 躺平学) or ‘the Lying Flat Clan’ (躺平族). Young people who believe in ‘lying flat’ are fed up with ‘involution,’ do not buy into social expectations about marriage and children and refuse to participate in the competitive struggle that starts at early as kindergarten and is all about the upcoming exam, the best result, the top school, the promising job, the longest hours, the next promotion. By ‘lying flat,’ Chinese young adults from middle and lower classes basically refuse to sweat over climbing higher up the social and economic ladder. They will only do the bare minimum and believe that upward social mobility has become an unattainable goal (Gong & Liu 2021, 2).

Although lying flat became a popular buzzword in China in 2021 after an online article titled “Lying Flat is Justice”2 went viral, it was already used by netizens long before that time.

“I was chatting with my colleague after work,” one Weibo user wrote in November of 2018: “We were talking about how unfortunate it is that if you don’t work, you don’t have money, and that if you work, you still don’t have money. You might as well stop working and lie flat. No pain, no feelings, no involution.”

Although the term ‘lying flat’ seems to indicate that the movement is all about passivity and weakness, it is actually more about social skepticism and taking matters into your own hands. One WeChat article by blogger Mao Talk (2021) compared the lying flat movement to the views held by the Greek philosopher Diogenes who believed society placed too much value on status, wealth, and material possessions, and was determined to live a simple life. He did not work and never married.

The ‘Lying Flat’ cat (image via Zhihu).

The Chinese originator of ‘lying flat,’ according to Mao Talk, is the philosopher Zhuangzi, who advocated that the best form of being is without a “sense of self” (“no-self”) and “to go with the flow” instead of being driven by social intercourse and power structures.

In an article published by the Guangming Daily in 2021, author Sun Xiaoting (孙小婷) also explained the Lying Flat movement in a similar light:

“Indeed, nowadays, people are able to look more dialectically at the various norms set by society and other people, and have a more multidimensional, tolerant viewpoint and wide-ranging definition of what constitutes ‘success’ and who is considered a ‘winner.’ They are also able to rationalize or even reject the values instilled by consumerism, success philosophy, and inspirational quotes, and they are brave enough to choose the lifestyle they believe is more comfortable. In fact, these young people who believe in ‘Lying Flat’ are not entirely like ‘salted fish’, and they are also different from the ‘Ge You Slouching’ and ‘Funeral Culture’ that appeared online a few years ago.3 Many of them have their own views on the meaning of life. They just do not want to be drawn into a social system where the order is already set up for them; they do not wish to get into this fast and crowded process in which people are traditionally pursuing the realization of “promotion and salary increase” and “buy a house and a car” through overtime work and other achievements. They are choosing to voluntarily withdraw from the pursuit of success and happiness within this social system, and the inner acceptance of the state of self is the preferred standard they are considering. This also explains why some young people quit their positions in big Internet companies and state-owned enterprises and choose to return to third- or fourth-tier cities to become ordinary coffee shop assistants or delivery riders, which means they take control of their personal time and regain more determinacy and leadership.”

Although the Lying Flat movement resembles the Buddhist Youth mentality and some other subcultures emerging over the past decade, there are clear differences.

Buddhist Youth mentality seems to come from a more negative mindset of anxiety and frustration, with people trying to find some sense of stability by adapting an ‘anything-goes’ attitude toward their life to protect themselves from disappointment and failure while they are perhaps still pursuing a path laid out for them by others. Those who believe in ‘lying flat,’ on the other hand, have readjusted their desires and goals for the future and decided to follow their own path.

Going Against the China Dream

Chinese official media tried to put an end to the diaosi trend after it first emerged by urging China’s young people to adopt a positive mindset, with state media outlet People’s Daily publishing an article titled “The Belitting of Oneself, Can We Give it a Rest?” (Zhou 2017, 243). Ever since the Lying Flat movement became an online trend, Chinese official media have also been condemning it.

In May of 2021, one commentary published by state media outlet Xinhua called the Lying Flat movement a “disgrace.” Although the article acknowledged the pressured faced by Chinese youth today, it stressed the necessity to uphold a confident and positive attitude. In 2022, ‘lying flat’ is still presented by Chinese officials and media as the road not to take.

In a recent interview with National People’s Congress representative Li Nannan (李楠楠) that was promoted on Weibo, the young delegate shared his take on involution and Lying Flat, urging Chinese youth to embrace competition and choose ‘involution’ over’ ‘lying flat’, since the latter is supposedly only about giving up and spreading “a negative atmosphere.” Another state media news report focused on Chinese under the age of 27 (post-95 and post-00 generations), their positive outlook on their career possibilities and their refusal to ‘lie flat.’

One reason why official channels label the ‘Lie Flat’ movement as such a negative one is because it goes against the ideals of the Chinese dream. The idea of the ‘China Dream’ has been ubiquitous in Chinese official media since Xi Jinping became president in 2013. The concept refers to a form of ‘national rejuvenation’ and a revival of the Chinese nation. At the National People’s Congress in March of 2013, Xi stated that, in order to achieve the Chinese dream “(..) we must spread the Chinese spirit, which combines the spirit of the nation with patriotism as the core and the spirit of the time with reform and innovation as the core.” He also stressed:

“In face of the mighty trend of the times and earnest expectations of the people for a better life, we cannot have the slightest complacency, or get the slightest slack at work.”

In the context of China’s road to rejuvenation, Chinese youth and young adults are seen as the “builders of socialism” who are supposed to contribute to the realization of the Chinese dream by having clear goals, strong ideals, and by working hard and actively start businesses and raise families. Youth subcultures such as the “Diaosi,” “Buddhist Youth” or “Lying Flat” are seen as having a negative impact on Chinese society since they allegedly do not contribute to a Chinese common ideal of socialism and reject the kind of lifestyle that is propagated by the Party (Wu & Ren 2018, 17).

Lately, the term ‘lying flat’ has also been used by official media in the context of China’s approach to fighting Covid19, following a surge in local outbreaks. While many other countries around the world are letting go of Covid19 measures, China is still adhering to its strict ‘zero Covid’ strategy, with millions of people facing yet another lockdown. It has triggered online discussions on whether the aggressive measures taken to prevent further spread of the virus are really the way forward for China’s Covid approach. But after the renowned Chinese doctor Zhang Wenhong stated that China cannot “lie flat” at this point of the Covid19 outbreak due to the potential death toll it might cause, a related hashtag went trending on social media platform Weibo (“Zhang Wenhong Does Not Agree with Lying Flat” #张文宏不同意躺平#).

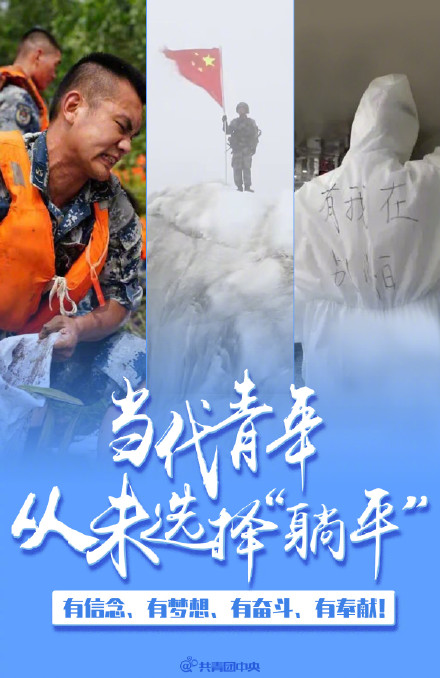

The term was previously used in a similar way by the Communist Youth League, which published a post on social media titled “Modern-day Youth Should Never Choose to Lie Flat” (“当代年轻人从未选择躺平”). In their post, the League honored China’s young frontline health workers, soldiers, scientists, and those defending the motherland with their lives, writing:

“They have faith, they have dreams, they face the struggle, they are dedicated – they never choose to ‘lie flat’!”

“Contemporary youth [should] never choose to “lie flat”” online poster by Communist Youth League.

By construing a clear distinction between those fighting for the nation and those “lying flat,” Chinese media suggest that ‘lying flat’ is an unpatriotic act, a type of behavior that shows a lack of devotion to one’s country.

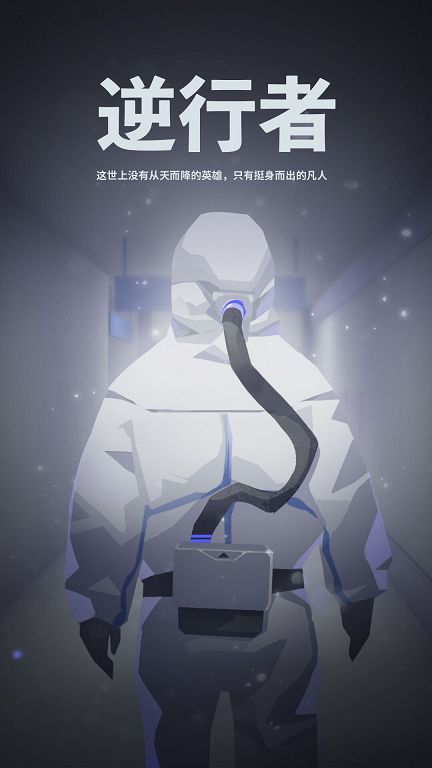

While those ‘lying flat’ are criticized, those ‘going against the tide’ are praised; nìxíngzhě (逆行者) is another buzzword from 2020 often used by state media to describe frontline workers and others as the ‘people going backward’, referring to those who dare to go back and face problems when everyone else is turning away.

‘Nìxíngzhě’ is a buzzword to describe the heroes going ‘backward’, facing the problems that others are turning away from.

The state media message that ‘lying flat’ is counterproductive seems to resonate with many online commenters. Although the movement was previously described as an “act of resistance” by Washington Post and other media, there now seems to be more resistance against this form of resistance.

Nevertheless, there is still a huge group of netizens supporting the ‘lying flat’ movement for the ideas it represents. One Weibo user says that the ‘Lie Flat’ movement should be viewed as an online “collective emotional catharsis” that helps people pull through their everyday life. Another post by one popular blogger that recently gained some traction online said:

“The post-1990 generation has seen the Foxconn Suicides, they saw the tragedy behind the [Bytedance] worker who collapsed, they’ve seen the world and have now discovered, the most important thing is to live (..). The capitalist exploitation has forced young people on the road of a ‘Buddhist mindset’. Are they resisting capital or are they forced to ‘lie flat’? That’s the essence of the problem.”

One commenter responded: “We are living in a socialist country, but judging the way in which workers are treated it might as well be a capitalist society.”

Ironically, not too long after tǎng píng or ‘lying flat’ became a buzzword, news came out that Chinese tech giant Alibaba had applied for trademark registration of tǎng píng to create an e-commerce app by that very same name.

Many people mocked the move. One person wrote: “You are shameless.” Another comment said: “The implied meaning behind ‘lying flat’ is about wanting less and reducing consumerism, but you capitalists really seize every opportunity, you are even willing to squeeze the last bit of values out of young people.”

Despite the changing meaning and different views on the Lie Flat trend in China’s online environment, one Chinese news article on the issue recently captured a common ground: “We need to find a balance in between ‘involution’ and ‘lying flat,’ so that life can be full of colors while also leaving blank spaces, because you can only find your best life when you can find the balance between tension and relaxation.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Footnotes:

1 Title: “The First Batch of the Post-90s Generation Has Taken the Cloth” (“第一批 90 后已经出家了”).

2 “躺平即是正义” (“Lying Flat is Justice”) was written by a blogger named “Kind-hearted Traveler” (好心的旅行家) on April 17, 2021. In the article, they described how they lead a minimalist lifestyle and explained the lying flat subculture as an alternative approach in life.

3 ‘Salted Fish Mentality,’ ‘Ge You-esque Slouching’ and ‘Funeral Culture’ are all buzzwords and online trends used by netizens since 2016 to express a sense of passivity and laziness in response to the ruthless job market and pressure to marry (also see Colville 2021).

References:

Colville, Alex. 2021. “Stop Trying to Make ‘Lying Flat’ Happen!” The World of Chinese, June 10 https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2021/06/stop-trying-to-make-lying-flat-happen/ [March 15, 2022].

Gong, Jing and Tingting Liu. 2021. “Decadence and Relational Freedom among China’s Gay Migrants: Subverting heteronormativity by ‘lying flat’.” China Information (December): 1-21.

Koetse, Manya. 2021. “The Concept of ‘Involution’ (Nèijuǎn) on Chinese Social Media.” What’s on Weibo, April 22 https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-concept-of-involution-neijuan-on-chinese-social-media/ [March 13, 2022].

Mao Talk. 2021. “躺平主义:历史、现实、真相 [Lying Flat-ism: History, Reality, Truth.” WeChat, June 26 https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzIxMDQ5NTQ3OA==&mid=2247483688&idx=1 &sn=9de2d27e74c354c91470436a9efe194c&chksm=9762f3b1a0157aa705ab15ca7f 4e6a7c8feaa8f8f448a4afae8a23db2c8009975a3b29fd2cee&scene=21#wechat_redirect [March 13, 2022].

Michels, Veronique. 2014. China Online: Netspeak and Wordplay used by over 700 million Chinese Internet Users. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing.

Sun, Xiaoting. 2021. “拒绝’内卷’年轻人开始信奉’躺平学’了? [Refusing Involution, Are Young People Starting to Believe in ‘Lying Flatology’”?]” (In Chinese). Guangming Daily, May 15 https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MjM5NzM0MzQ4MQ==&mid=2654670779&idx =1&sn=f9e01056429a196c701a223580d2a1aa&chksm=bd14d62d8a635f3b42b2c6fe04175fd807d1017a6a0d030fbc7bc995cb8f36aaede7bfdf78f2&scene=0&xtrack=1#rd [March 14, 2022].

Sun, Jiahui. 2017. “How to Be a ‘Buddha-like Youth’.” ECNS, December 26 https://www.ecns.cn/learning-Chinese/2017/12-26/285916.shtml [March 12, 2022].

Szablewicz Marcella. 2014. “The ‘Losers’ of China’s Internet: Memes as ‘Structures of Feeling’ for Disillusioned Young Netizens.” China Information 28(2): 259-275.

Wu, Hongjuan and Ren Ying. 2018. “佛系青年”人生观误区及其引导 [A Brief Analysis on and Guidance for Fever in Buddha-like Youth]” (In Chinese). Journal of Wuhu Institute of Technology. 2018 (02): 15-18.

Zhou, Cao. 2017. “Internet Meme Songs in China and the “Diaosi” Identity of Youth Culture.” In: Ethnic and Cultural Identity in Music and Song Lyrics, Victor Kennedy and Michelle Gadpaille (eds), 241-249. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Any other sources not listed here are hyperlinked within the text.

Copyright: Goethe-Institut USA. Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China and Covid19

Sick Kids, Worried Parents, Overcrowded Hospitals: China’s Peak Flu Season on the Way

“Besides Mycoplasma infections, cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

Published

8 months agoon

November 22, 2023

In the early morning of November 21, parents are already queuing up at Xi’an Children’s Hospital with their sons and daughters. It’s not even the line for a doctor’s appointment, but rather for the removal of IV needles.

The scene was captured in a recent video, only one among many videos and images that have been making their rounds on Chinese social media these days (#凌晨的儿童医院拔针也要排队#).

One photo shows a bulletin board at a local hospital warning parents that over 700 patients are waiting in line, estimating a waiting time of more than 13 hours to see a doctor.

Another image shows children doing their homework while hooked up on an IV.

Recent discussions on Chinese social media platforms have highlighted a notable surge in flu cases. The ongoing flu season is particularly impacting children, with multiple viruses concurrently circulating and contributing to a high incidence of respiratory infections.

Among the prevalent respiratory infections affecting children are Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, influenza, and Adenovirus infection.

The spike in flu cases has resulted in overcrowded children’s hospitals in Beijing and other Chinese cities. Parents sometimes have to wait in line for hours to get an appointment or pick up medication.

According to one reporter at Haibao News (海报新闻), there were so many patients at the Children’s Hospital of Capital Institute of Pediatrics (首都儿科研究所) on November 21st that the outpatient desk stopped accepting new patients by the afternoon. Meanwhile, 628 people were waiting in line to see a doctor at the emergency department.

Reflecting on the past few years, the current flu season marks China’s first ‘normal’ flu peak season since the outbreak of Covid-19 in late 2019 / early 2020 and the end of its stringent zero-Covid policies in December 2022. Compared to many other countries, wearing masks was also commonplace for much longer following the relaxation of Covid policies.

Hu Xijin, the well-known political commentator, noted on Weibo that this year’s flu season seems to be far worse than that of the years before. He also shared that his own granddaughter was suffering from a 40 degrees fever.

“We’re all running a fever in our home. But I didn’t dare to go to the hospital today, although I want my child to go to the hospital tomorrow. I heard waiting times are up to five hours now,” one Weibo user wrote.

“Half of the kids in my child’s class are sick now. The hospital is overflowing with people,” another person commented.

One mother described how her 7-year-old child had been running a fever for eight days already. Seeking medical attention on the first day, the initial diagnosis was a cold. As the fever persisted, daily visits to the hospital ensued, involving multiple hours for IV fluid administration.

While this account stems from a single Weibo post within a fever-advice community, it highlights a broader trend: many parents swiftly resort to hospital visits at the first signs of flu or fever. Several factors contribute to this, including a lack of General Practitioners in China, making hospitals the primary choice for medical consultations also in non-urgent cases.

There is also a strong belief in the efficacy of IV infusion therapy, whether fluid-based or containing medication, as the quickest path to recovery. Multiple factors contribute to the widespread and sometimes irrational use of IV infusions in China. Some clinics are profit-driven and see IV infusions as a way to make more money. Widespread expectations among Chinese patients that IV infusions will make them feel better also play a role, along with some physicians’ lacking knowledge of IV therapy or their uncertainty to distinguish bacterial from viral infections (read more here)

To prevent an overwhelming influx of patients to hospitals, Chinese state media, citing specialists, advise parents to seek medical attention at the hospital only for sick infants under three months old displaying clear signs of fever (with or without cough). For older children, it is recommended to consult a doctor if a high fever persists for 3 to 5 days or if there is a deterioration in respiratory symptoms. Children dealing with fever and (mild) respiratory symptoms can otherwise recover at home.

One Weibo blogger (@奶霸知道) warned parents that taking their child straight to the hospital on the first day of them getting sick could actually be a bad idea. They write:

“(..) pediatric departments are already packed with patients, and it’s not just Mycoplasma infections anymore. Cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. And then, of course, those with bad luck are cross-infected with multiple viruses at the same time, leading to endless cycles. Therefore, if your child experiences mild coughing or a slight fever, consider observing at home first. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

The hashtag for “fever” saw over 350 million clicks on Weibo within one day on November 22.

Meanwhile, there are also other ongoing discussions on Weibo surrounding the current flu season. One topic revolves around whether children should continue doing their homework while receiving IV fluids in the hospital. Some hospitals have designated special desks and study areas for children.

Although some commenters commend the hospitals for being so considerate, others also remind the parents not to pressure their kids too much and to let them rest when they are not feeling well.

Opinions vary: although some on Chinese social media say it's very thoughtful for hospitals to set up areas where kids can study and read, others blame parents for pressuring their kids to do homework at the hospital instead of resting when not feeling well. pic.twitter.com/gnQD9tFW2c

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) November 22, 2023

By Manya Koetse, with contributions from Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China and Covid19

Repurposing China’s Abandoned Nucleic Acid Booths: 10 Innovative Transformations

Abandoned nucleic acid booths are getting a second life through these new initiatives.

Published

1 year agoon

May 19, 2023

During the pandemic, nucleic acid testing booths in Chinese cities were primarily focused on maintaining physical distance. Now, empty booths are being repurposed to bring people together, serving as new spaces to serve the community and promote social engagement.

Just months ago, nucleic acid testing booths were the most lively spots of some Chinese cities. During the 2022 Shanghai summer, for example, there were massive queues in front of the city’s nucleic acid booths, as people needed a negative PCR test no older than 72 hours for accessing public transport, going to work, or visiting markets and malls.

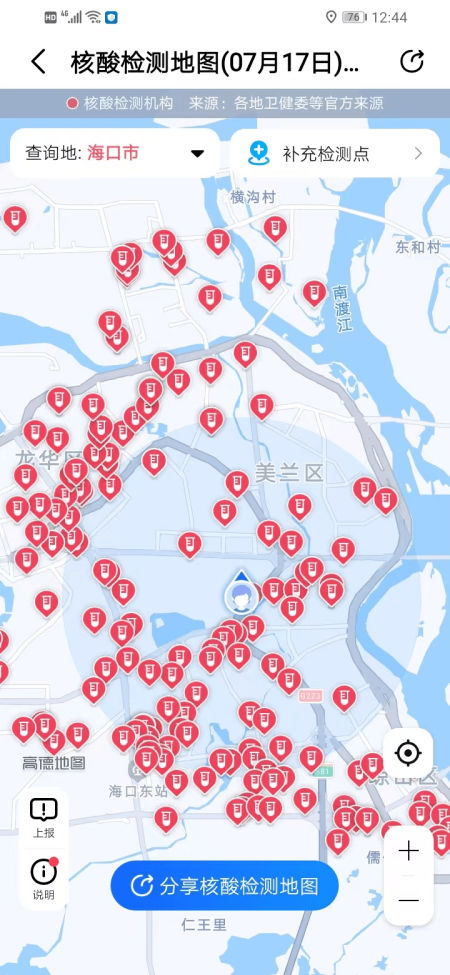

The word ‘hésuān tíng‘ (核酸亭), nucleic acid booth (also:核酸采样小屋), became a part of China’s pandemic lexicon, just like hésuān dìtú (核酸地图), the nucleic acid test map lauched in May 2022 that would show where you can get a nucleic test.

Example of nucleic acid test map.

During Halloween parties in Shanghai in 2022, some people even came dressed up as nucleic test booths – although local authorities could not appreciate the creative costume.

Halloween 2022: dressed up as nucliec acid booths. Via @manyapan twitter.

In December 2022, along with the announced changed rules in China’s ‘zero Covid’ approach, nucleic acid booths were suddenly left dismantled and empty.

With many cities spending millions to set up these booths in central locations, the question soon arose: what should they do with the abandoned booths?

This question also relates to who actually owns them, since the ownership is mixed. Some booths were purchased by authorities, others were bought by companies, and there are also local communities owning their own testing booths. Depending on the contracts and legal implications, not all booths are able to get a new function or be removed yet (Worker’s Daily).

In Tianjin, a total of 266 nucleic acid booths located in Jinghai District were listed for public acquisition earlier this month, and they were acquired for 4.78 million yuan (US$683.300) by a local food and beverage company which will transform the booths into convenience service points, selling snacks or providing other services.

Tianjin is not the only city where old nucleic acid testing booths are being repurposed. While some booths have been discarded, some companies and/or local governments – in cooperation with local communities – have demonstrated creativity by transforming the booths into new landmarks. Since the start of 2023, different cities and districts across China have already begun to repurpose testing booths. Here, we will explore ten different way in which China’s abandoned nucleic test booths get a second chance at a meaningful existence.

1: Pharmacy/Medical Booths

Via ‘copyquan’ republished on Sohu.

Blogger ‘copyquan’ recently explored various ways in which abandoned PCR testing points are being repurposed.

One way in which they are used is as small pharmacies or as medical service points for local residents (居民医疗点). Alleviating the strain on hospitals and pharmacies, this was one of the earliest ways in which the booths were repurposed back in December of 2022 and January of 2023.

Chongqing, Tianjin, and Suzhou were among earlier cities where some testing booths were transformed into convenient medical facilities.

2: Market Stalls

In Suzhou, Jiangsu province, the local government transformed vacant nucleic acid booths into market stalls for the Spring Festival in January 2022, offering them free of charge to businesses to sell local products, snacks, and traditional New Year goods.

The idea was not just meant as a way for small businesses to conveniently sell to local residents, it was also meant as a way to attract more shoppers and promote other businesses in the neighborhood.

3: Community Service Center

Small grid community center in Shizhuang Village, image via Sohu.

Some residential areas have transformed their local nucleic acid testing booths into community service centers, offering all kinds of convenient services to neighborhood residents.

These little station are called wǎnggé yìzhàn (网格驿站) or “grid service stations,” and they can serve as small community centers where residents can get various kinds of care and support.

4: “Refuel” Stations

In February of this year, 100 idle nucleic acid sampling booths were transformed into so-called “Rider Refuel Stations” (骑士加油站) in Zhejiang’s Pinghu. Although it initially sounds like a place where delivery riders can fill up their fuel tanks, it is actually meant as a place where they themselves can recharge.

Delivery riders and other outdoor workers can come to the ‘refuel’ station to drink some water or tea, warm their hands, warm up some food and take a quick nap.

5: Free Libraries

image via sohu.

In various Chinese cities, abandoned nucleic acid booths have been transformed into little free libraries where people can grab some books to read, donate or return other books, and sit down for some reading.

Changzhou is one of the places where you’ll find such “drifting bookstores” (漂流书屋) (see video), but similar initiatives have also been launched in other places, including Suzhou.

6: Study Space

Photos via Copyquan’s article on Sohu.

Another innovative way in which old testing points are being repurposed is by turning them into places where students can sit together to study. The so-called “Let’s Study Space” (一间习吧), fully airconditioned, are opened from 8 in the morning until 22:00 at night.

Students – or any citizens who would like a nice place to study – can make online reservations with their ID cards and scan a QR code to enter the study rooms.

There are currently ten study booths in Anji, and the popular project is an initiative by the Anji County Library in Zhejiang (see video).

7: Beer Kiosk

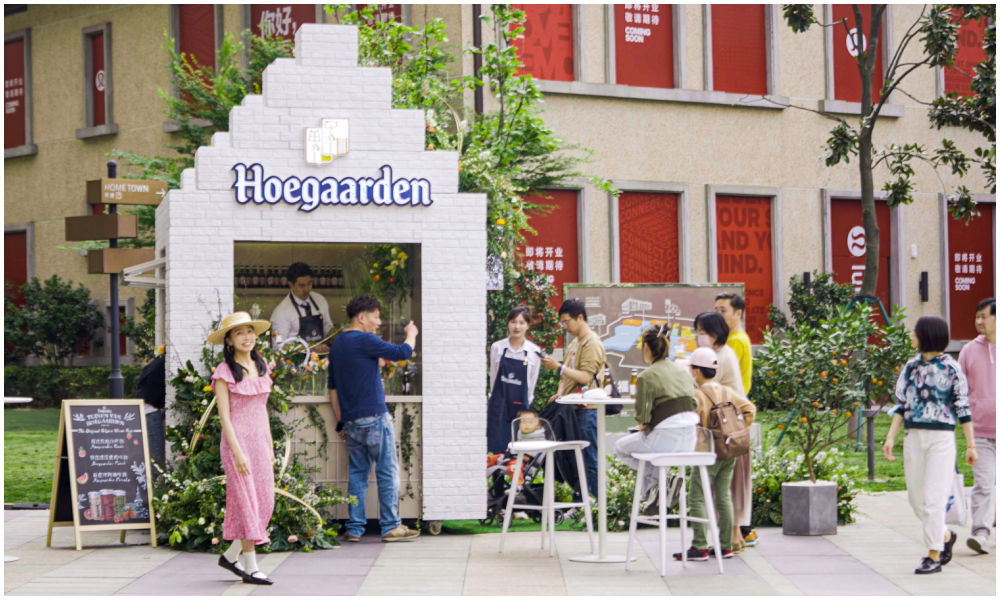

Hoegaarden beer shop, image via Creative Adquan.

Changing an old nucleic acid testing booth into a beer bar is a marketing initiative by the Shanghai McCann ad agency for the Belgium beer brand Hoegaarden.

The idea behind the bar is to celebrate a new spring after the pandemic. The ad agency has revamped a total of six formr nucleic acid booths into small Hoegaarden ‘beer gardens.’

8: Police Box

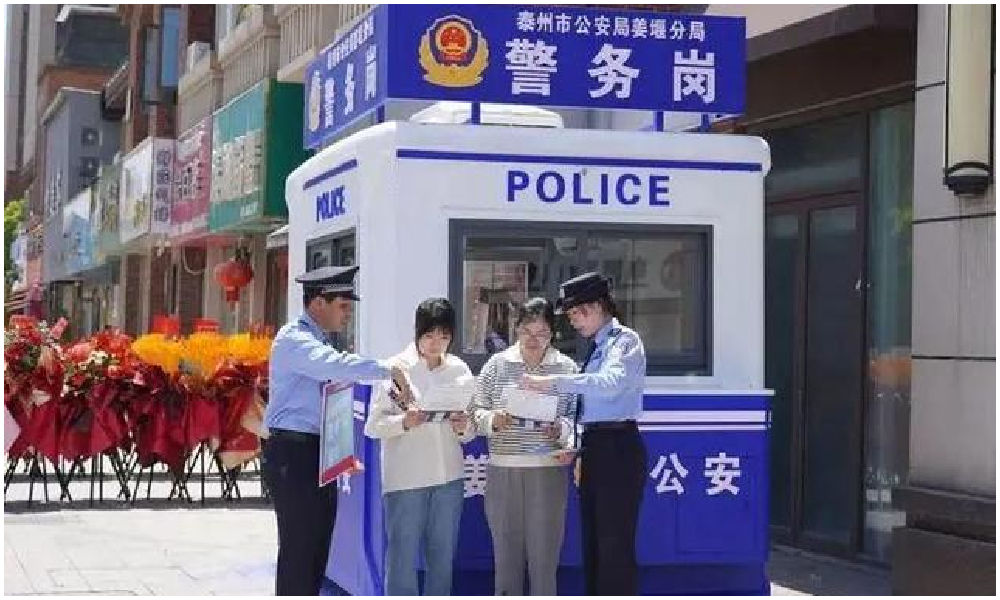

In Taizhou City, Jiangsu Province, authorities have repurposed old testing booths and transformed them into ‘police boxes’ (警务岗亭) to enhance security and improve the visibility of city police among the public.

Currently, a total of eight vacant nucleic acid booths have been renovated into modern police stations, serving as key points for police presence and interaction with the community.

9: Lottery Ticket Booths

Image via The Paper

Some nucleic acid booths have now been turned into small shops selling lottery tickets for the China Welfare Lottery. One such place turning the kiosks into lottery shops is Songjiang in Shanghai.

Using the booths like this is a win-win situation: they are placed in central locations so it is more convenient for locals to get their lottery tickets, and on the other hand, the sales also help the community, as the profits are used for welfare projects, including care for the elderly.

10: Mini Fire Stations

Micro fire stations, images via ZjNews.

Some communities decided that it would be useful to repurpose the testing points and turn them into mini fire kiosks, just allowing enough space for the necessary equipment to quickly respond to fire emergencies.

Want to read more about the end of ‘zero Covid’ in China? Check our other articles here.

By Manya Koetse,

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

confuciuscries

May 26, 2022 at 5:39 am

ahhhhh. the acceleration of Convergent Devolution and its infiltration into society at large are finally in play. a big salute from our advanced degenerate brethren of the west who LDAR (ie ‘lay down and rot’) and from the 三和大神 in longhua, shenzhen. wuts next??? when will we all finally transform into balding h0mosexual post-op cockroaches?

charles baer

May 29, 2022 at 4:10 am

I enjoyed reading this article .

Suprith

October 13, 2022 at 2:52 pm

I am also lying flat these days. I worked a very hard in school and College to get good grades and I was a topper in my school. But only after graduation, I faced the slap of reality, couldn’t get a decent paying job and had to take up a factory job that paid just 56 cents(US) per hour, and had to struggle a lot. Now with some savings I’ve quit my job and decided to lie flat, actually many people here in India do like this, but they just don’t call it lying flat. Now I’m having peace of mind and calmness in my life.

Though i know i need to go back to work sooner or later, i like this break and even back in work, i won’t toil or work hard, I’ll work just enough to live peacefully, without giving in to society’s expectations..