Featured

About Xi Jinping’s Third Term Trending on Weibo

A hashtag related to Xi Jinping’s third term received over 1.2 billion views on Weibo.

Published

3 years agoon

It is the news that was widely expected yet still made international headlines on Friday, March 10: Xi Jinping secured his third term as president.

The official appointment happened after the members of the National People’s Congress (NPC) voted unanimously for Xi Jinping. There was no other candidate.

In February 2018, it was announced that the constitution of mainland China would change in some important ways, including the indefinite rule for Xi Jinping after his second five-year term of the presidency would end in 2023.

At that time, What’s on Weibo reported how the news of a third Xi Jinping term caused some consternation on Chinese social media, where some called the idea of Xi’s potential indefinite rule “scary” and some netizens joked about “our emperor has received the Mandate of Heaven, so we have to kneel and accept.”

Now, three years later, there is less room for such discussions at a time of the Two Sessions, when the social media environment is always more controlled.

The online discourse surrounding Xi Jinping is also less playful than before. In 2017, during the 19th Party Congress, an online game that allowed netizens to “clap” for Xi became a social media hit.

Around the same time, state media outlets published short videos or gifs featuring Xi as a cartoon character. In 2023, the overall tone of state media reports on Xi is much more serious.

On Friday, Xi Jinping’s third term went top trending on Weibo, where one related topic received over 800 million views. A day later the hashtag had over 1.2 billion clicks (#习近平当选中华人民共和国主席#).

While refreshing and searching on the Weibo platform, some comment sections were closing and opening, some videos went online and offline, and even Xi’s own name was temporarily unsearchable on the Weibo site, suggesting that online control systems were going into overdrive.

A video of Xi Jinping taking his oath received over 75 million views (times played) and over 14,000 comments on Weibo.

“Serve the people,” “congratulations,” and “strong country, happy people,” were among the typical comments listed in the reply sections below the news posts on Xi’s third term.

Another hashtag was also promoted on Chinese social media by state broadcaster CCTV, namely that of Xi Jinping always focusing on putting the people first (#始终把人民放在心中最高的位置#).

The phrase “the people first” (人民至上 rénmín zhìshàng), also “putting the people in the first place,” is an important part of the Party’s ‘people-based, people-oriented’ governing concept. The phrase became especially relevant as part of Xi Jinping’s now-famous “put people and their life first” slogan (人民至上,生命至上, rénmín zhìshàng, shēngmìng zhìshàng), which became one of the most important official phrases of 2020 in light of the fight against Covid19.

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Memes & Viral

Two Sessions, a Celebrity Meltdown, and the Rise of China’s “Forget It” Mindset

Inside this week’s trends: Two Sessions talking points, a massive celebrity meltdown, and a pet gym in Shanghai charging $275 a month.

Published

1 day agoon

March 8, 2026

🔥 China Trend Watch (week 10 | 2026) Part of Eye on Digital China by Manya Koetse, China Trend Watch is an overview of what’s trending and being discussed on Chinese social media. The previous newsletter was a chapter dive into the Chinese online discourse surrounding the Iran war. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

“Taiwan never was, is not, and never will become a country,” China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) said during the annual press conference this Sunday on the sidelines of the Two Sessions, China’s most important political gathering of the year.

Besides Taiwan, Wang Yi spoke about the Iran war (“should not have happened”), Palestine (“two-state solution”), Sino-American relations (“mutual respect”), and more. Although there are undoubtedly many things to disagree on, one thing Wang mentioned more than once is just how turbulent the world we live in today has become – I think we all agree about that.

If you missed Wednesday’s newsletter about China’s online discourse on the Iran war, you can find it here. In this edition, let’s dive into other trending topics beyond that conflict, which dominated much of the discussion this week.

Quick Scroll

-

- 🌸 Women’s Day, March 8, falls on a Sunday in 2026, which ironically means women are not entitled to their usual half-day off under China’s national holiday regulations this time.

- 🤖 China has released its first national standards framework for humanoid robots and embodied AI, unveiled at an industry conference in Beijing. The move signals Beijing’s push to accelerate commercialization and large-scale production as China positions itself as a global leader in humanoid robotics.

- 🎬 Zhang Yimou’s latest crime thriller Scare Out (惊蛰无声), about national security officers battling enemy spies and produced under the guidance of China’s Ministry of State Security, has become the highest-grossing crime film of the Spring Festival season at the Chinese box office.

- 🚗 A Chinese Lynk & Co Z20 car owner recently crashed into a road divider at night after asking the car’s voice assistant to turn off all reading lights, but the system mistakenly turned off the headlights instead. When he tried to turn them back on, the AI assistant replied, “I can’t do that yet.” The company has since apologized, but the incident has sparked criticism of automakers putting smart features ahead of safety.

- 🐶 A pet gym in Shanghai charging around 2,000 yuan ($275) for a monthly membership shows just how hot China’s pet economy is becoming. At the upscale gym, dogs can walk on treadmills, swim, get massages, and receive one-on-one training.

- 🍑 The latest costume drama Pursuit of Jade (逐玉), which premiered on iQIYI and Tencent Video on March 6, has become a breakout success during its opening weekend, setting a record for the fastest-rising drama on Weibo, driven by a massive fandom known as the “Peach Blossom Chasers” (桃花逐理人).

- 🚆 A Chinese student suffered cardiac arrest after traveling 31 hours in a hard-seat train back to school after Spring Festival. She survived, with doctors diagnosing ‘economy-class syndrome’ (经济舱综合征): blood clots caused by prolonged immobile sitting.

- 📱 The Chinese Honor brand came out with the world’s thinnest Android tablet this week. The MagicPad 4 measures just 4.8mm thick, making it thinner than the iPad Pro or Samsung Galaxy Tab. As it also debuted OpenClaw collaboration technology, becoming the first commercial device to officially support running open-source AI agents, the device became a much-discussed ‘wannahave.’

What Really Stood Out This Week

Holiday Debt, Bride Prices, and Meme CEOs: What’s Trending from China’s Two Sessions

The annual Two Sessions—China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) plenary and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC)—are convening from March 4 to March 11. As usual, they’ve become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media this week, alongside the ongoing developments in Iran.

This year, topics such as pensions, holidays, healthcare, tech, and AI have been receiving special attention. Here are three talking points that have generated considerable online discussion.

📍 One issue that netizens especially seemed to care about is the phenomenon of China’s “compensatory working day” system (调休 tiáoxiū), which allows people longer holiday blocks (such as seven days for the National Day holiday, or nine days for the recent Spring Festival) but requires people to make up for some of those days by working weekend days on either side of the holiday.

NPC delegate Tian Xuan (田轩) has proposed reducing or avoiding the use of these “make-up days,” and instead increasing the number of public holidays. The proposal is receiving strong support from workers who have long been frustrated by this system of “borrowing” free days, which creates a sense of being in holiday “debt.”

📍 Another proposal that went viral concerns child safety and stricter punishment for sex offenders. Female NPC delegate Fang Yan (方燕) suggested that convicted sex offenders against minors should be banned from professions involving close contact with children, prohibited from entering kindergartens and schools, and subjected to mandatory electronic location monitoring after serving their sentence.

📍 NPC delegate Zhang Qiang (张强) put forward another proposal that generated online discussions, focusing on the topic of China’s bride prices (彩礼 cǎilǐ), payments made by the groom’s family to the bride’s family. The issue has been widely debated for years as bride prices have been skyrocketing in rural China, where there are more men of marriageable age than women.

Zhang proposes that, in line with village rules, bride prices should be capped at no more than 20,000 yuan (US$ 2,900). Zhang spoke from experiences from his own village, where some bride prices rose to a staggering 188,000 yuan (US$27,260) – which allegedly almost made the marriage fall apart before it even started. Although many agree that there should be measures to break the cycle that puts rural families in debt, others think that the government shouldn’t intervene in private family customs.

📍 The most discussed NPC delegates are Xiaomi CEO Lei Jun (雷军) and Zhou Yunjie (周云杰), top executive at the Haier Group. Xiaomi is one of China’s leading smartphone and electronics makers, while Haier is one of the country’s largest home-appliance groups. The two delegates already appeared together at the Two Sessions last year, when their contrasting roles drew attention: one representing China’s younger, fast-moving digital companies, the other the face of China’s older, traditional manufacturing industry.

This year, the two appearing together has become a source of memes, often portraying Lei Jun as the more playful, younger figure leading Zhou Yunjie into the world of social media. The stark difference between the two business leaders is what strikes a chord—Zhou is seen as the more serious, traditional senior business leader. The pair is affectionately called the “HaiMi Brothers” (海米兄弟) by netizens.

Many netizens hope that beyond the Two Sessions, Lei and Zhou will continue to hang out and collaborate more by combining their strengths and expertise.

The Celebrity Drama Taking Over Chinese Social Media

Earlier this week, I promised to update you on the juicy celebrity story that almost managed to rival the Iran war as one of the most talked-about topics of the week—despite being entirely insignificant in comparison (which, of course, is exactly what makes it so irresistible🍿).

At the heart of the story is a decade-old celebrity feud involving singer Joker Xue (薛之谦 Xue Zhiqian) that was reignited by his messy former girlfriend Li Yutong (李雨桐). On March 2, she posted a chaotic online rant filled with grievances against Xue, who left her in 2017 before reconciling with his ex-wife. Apparently, there is still a lot of unprocessed grief from those days, because there is no other obvious reason to explain why Li decided to share her since-deleted meltdown with millions of Chinese netizens earlier this week.

In more than 20 posts of threats and dirty laundry—from “I will expose everything” to accusing Xue of forcing her into an abortion and filing a public police report against him for bigamy—Li dragged her ex down while also mentioning details about Xue being nasty toward celebrity colleagues. Among them, she referenced mean remarks about Chinese pop star Zhang Jie (张杰), also known as Jason Zhang. With more than 81 million Weibo followers and record-breaking ticket sales for 12 consecutive concerts at Beijing’s National Stadium, he is about as famous as you can get. His wife, Xie Na (谢娜), is arguably the most recognizable female television host in China.

The situation then spiraled into a much bigger controversy when fans began linking Li’s claims about Joker Xue’s remarks to a 2017 comedy roast program (吐槽大会 Tǔcáo Dàhuì). Soon after, Xie Na published an open letter on her personal Weibo directly addressing Joker Xue and demanding a formal apology to her husband Zhang Jie for the remarks—essentially accusing him of belittling Zhang’s supposedly “low-class” singing style.

As if that wasn’t enough, another ex-girlfriend entered the scene with a Weibo post. Duan Xi (段曦), seemingly triggered by Xie Na’s intervention, asked: if people are publicly demanding apologies now—“can I have one too?” In a lengthy message, she recounted how she fell into loneliness and depression after Xie Na entered the life she had shared with Zhang Jie more than two decades ago, suggesting that their past behavior might not have been entirely clean either.

Should we care about this story? Not at all. But it contains all the elements of a soap drama. Former lovers seeking revenge, bitter jealousy, and long-standing feuds. Reality, in this case, is hardly less dramatic than a scripted series. Above all, it offers a glimpse into the lives of China’s rich and famous. Although they often seem far removed from ordinary netizens, these occasional meltdown moments reveal something much more familiar: fragile egos, messy relationships, and very public outbursts.

There is also a commercial side to it. Besides other celebrities jumping in to boost their own online visibility and renew their relevance, the entire spectacle is lucrative for Weibo, once the central stage of China’s celebrity culture. Even though regulators have spent years trying to curb celebrity gossip and “vulgar” online content on platforms like Weibo, it remains exactly the kind of content that generates the most traffic and clicks.

In between news about the war in Iran and China’s Two Sessions, it is stories like these that keep people returning to social media—not for foreign news or state media narratives, but for drama.

On the Feed

The Little “Coal Mining” Panda

One little panda cub born last summer at a conservation base in Sichuan has recently gone viral for its muddy black appearance, with some joking that it’s “cosplaying” a black bear and others calling it the “coal mining bear” (挖煤小熊). The cub, now often referred to as the “Su Jin cub” (苏锦崽) since giant panda Su Jin is its mother, has quickly become a crowd favorite. Although there has been a lot of speculation about its color, the explanation is simple: even though staff wipe it down every day, little Su Jin just loves rolling through the mud.

Word of the Week

“算了型人格” (suànle xíng rénge — “forget-it personality type”)

The “forget-it personality” can be seen as a kind of coping strategy for younger generations navigating modern life, where they face information overload and decision fatigue. In that sense, it can be added to the list of other self-labeling terms we’ve seen in Chinese youth culture before, from “lying flat” (躺平 tǎng píng) to “rat people” (老鼠人 lǎoshǔrén).

The “forget-it personality,” however, is somewhat more pragmatic: it reflects a day-to-day attitude in which someone decides it’s simply not worth the trouble to fuss over something. You say “forget it” because you already have enough on your plate.

One thing these terms have in common is a sense of emotional exhaustion, yet adopting such an attitude is not necessarily about giving up; for some people it has even become something to aspire to.

One Douyin user wrote:

“I like browsing online, but sometimes comments make me so angry that I want to reply. Then I think about how many words I’d have to type and how much I’d have to think about the response, and suddenly I’m too lazy to comment. My temper is bad, but I also hate hassle.”

—That’s a wrap.

See you next edition.

Best,

Manya

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo. Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. If you no longer wish to receive these newsletters, or are receiving duplicate editions, you can unsubscribe at any time.

Chapter Dive

Inside the Great Chinese Debate Over the Iran War

From official reactions and armchair generals to women’s rights defenders: China’s online discourse surrounding the war in Iran.

Published

5 days agoon

March 4, 2026

This is a deep dive into how the latest developments in Iran are being discussed and reflected on in China, focusing on four aspects: (1) China’s official response, (2) key dynamics within the online discourse, (3) clashing views among key opinion leaders, and (4) polarized reactions within grassroots online communities.

“We’re witnessing history.” That was one sentiment seemingly shared by almost everyone across Chinese social media as news broke of a joint US-Israeli strike on Iran on February 28. Over the past few days, military operations in Iran, Iran’s retaliatory strikes against US military bases across the Middle East, and the death of Supreme Leader Khamenei (哈梅内伊) have been top trending topics across virtually all Chinese social media platforms, from Kuaishou to Douyin and beyond.

Even with the Two Sessions about to start, roughly one in every five posts on Weibo’s main feed have been about Iran in the four days since the attack. Some hashtags there, such as “Khamanei Killed” (#哈梅内伊遇害#), have accumulated over a billion views in less than three days. News of a Chinese civilian killed in the attack reached over 250 million views in a day (#伊朗一名中国公民遇难#).

China’s online responses to the developments in Iran cannot be captured in a few sentences. Interpretations vary among netizens, online commentators, and official actors.

At the same time, sentiments have shifted in response to ongoing strikes and emerging reports, ranging from geopolitical and economic concerns to questions about what this war means for ordinary Chinese citizens.

● China’s Official Response and State Media Coverage

One element that has not changed over the past few days—and was to be expected—is China’s official disapproval of the US-Israeli strikes on Iran.

China-Iran relations have deepened since 1979, and the two countries have been economic and military allies for decades. China is Iran’s largest trading partner, and the Sino-Iranian partnership is strategically important to China, especially in light of the Belt and Road Initiative.

On Saturday, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded, stating that China was “highly concerned” about the military operations, calling for an immediate halt to attacks, urging against further escalation, and advocating a return to diplomatic negotiations. A day later, Beijing described the killing of Iran’s highest leader as a “severe violation of Iran’s sovereignty and security” and a trampling of the principles of the UN Charter.

In a phone conversation with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) called the attack “unacceptable” (‘不可接受”) and outlined China’s three-point position:

– Immediately cease military operations.

– Return to dialogue and negotiations as soon as possible.

– Jointly oppose these actions that ignore the rules-based order.

What’s particularly noticeable in the official Chinese hashtags surrounding developments in Iran is that they closely align with the perspective of Iranian media reports rather than Western coverage.

Beyond voicing China’s official expression of concern about the war and highlighting the safety and evacuation of Chinese citizens abroad, the majority of official media hashtags fall into four main categories. Although the reporting tone is relatively neutral, the selection of hashtags—and, because this is social media, the discussions they generate—reveals a clear editorial direction in how the US-Israel war on Iran is framed.

📢 1. Iranian Regime Shock: Continuity Over Collapse

State-media-backed narratives on Chinese social media frame the military attack on Iran as a systemic shock to the regime. While focusing on the leadership crisis, presented as directly caused by the US and indirectly fueled by “internal betrayal,” these stories ultimately prioritize themes of Iranian institutional continuity and the preservation of order, with no attention to popular resistance or potential grassroots power shifts.

Hashtag Examples:

- CCTV: “How Will Iran’s New Supreme Leader Arise?” #伊朗新的最高领袖如何产生#

- China News Service: “Iran Interim Leadership Committee Begins Work” #伊朗临时领导委员会开始工作#

- Global Times: “Internal Traitors Are Iran’s Deadly Danger” #伊朗的致命隐患是内奸#

- China News Service: “Iran’s Foreign Minister Says the US and Israel Cannot Overthrow the Iranian Regime” #伊外长称美以不可能推翻伊朗政权#

📢 2. Iran Fights Back: Agency & Retaliation

There is another set of hashtags that mainly focus on Tehran’s retaliation, military actions, and refusal to negotiate with the United States. These hashtags promote narratives about the agency and strength of Iran’s leadership, and its successful resistance to US-Israeli attacks.

Hashtag Examples:

- Global Times: “Advisor to Iran’s Supreme Leader Promises Further Retaliation Against US and Israel” #伊朗最高领袖顾问承诺进一步报复美以#

- CCTV: “Iranian President Says Enemies Will Be Driven to Despair” #伊朗总统称将让敌人绝望#

- CCTV: “Iranian Missiles Break Through Israel’s Defense System” #伊朗导弹突破以色列防御系统#

- Global Times: “Iran Says It Won’t Talk to US” #伊朗称不会与美国进行谈判#

- CCTV: “Iran Says It’s Preparing for a Long-Term War” #伊朗称已准备好长期战争#

- China Blue News: “Iranian Foreign Minister Says: Though the Leader Was Killed, Iran Will Not Fall” #伊朗外长称领袖虽遇难但伊朗不会倒下#

📢 3. Focus on Iranian Suffering and Human Impact

A third overarching narrative seen in the hashtags is a moral one that highlights death & destruction brought by US–Israeli strikes in Iran and beyond, and their impact on civilians. Especially on Saturday, this perspective became prominent through many hashtags emphasizing how a girls’ elementary school in Minab, southern Iran, was reportedly hit by missiles during the military operation, resulting in around 150 deaths, according to Iranian media.

Hashtag examples:

- CCTV: “US–Israeli Attack Kills 555 People” #美以袭击致伊朗555人死亡#

- China Blue News: “Hospital Bombed: Iranian Medics Rescue Baby from Incubator” #医院被炸伊朗医护抢出保温箱内婴儿#

- Dazhong News: “Iranian People Do Their Best to Escort Chinese to Safety” #伊朗人民拼全力护送中国人安全离开#

📢 4. US–Israeli Actions as Global Destabilization

Another trend in Chinese media headlines over the past few days portrays US and Israeli actions as not only illegitimate and irresponsible but also as the trigger for wider global ripple effects. One post by People’s Daily claimed that the US and Israel are “undermining the foundations of peace established after World War II,” and a provocative AI video posted by China Daily, titled “The Bloody Arsenal,” suggested that the US only engages in bloody warfare for profit and power.

Hashtag examples:

- China News Service: “US-Israel Strike May Lead to a Global Food Crisis” #美以袭击伊朗或引发全球粮食危机#

- CCTV International: “America and Israel Can’t Attack Iran and then Walk Away” #美以不可能打了伊朗就一走了之#

- The Paper: “U.S. Strikes Iran Without Congressional Authorization” #美国未经国会授权空袭伊朗#

- Xinhua: “Iran Will Not Allow a Single Drop of Oil to Flow Out” #伊朗不允许一滴石油流出#

- CCTV: “Protests in US Capital Against US–Israel Strikes on Iran” #美首都集会抗议美以对伊朗动武#

“The Bloody Arsenal” AI video cover, by China Daily. Editor-in-charge, He Si (何思)

Notably, none of the approximately 450 Chinese media hashtags I have gathered and analyzed from Feb 28-March 4 portray Iranians as welcoming American intervention or celebrating Khamenei’s death. Nor do they express any pro-US or pro-Israeli sentiment, directly or indirectly.

Besides Iranian women appearing as victims of strikes, there are also no trending headlines highlighting Iranian women’s voices or women’s rights in this context.

Another viewpoint missing from these official media talking points is how the conflict is directly affecting China, diplomatically or economically, and how China’s own interests are being harmed in this war.

● Beyond the Headlines: Debate, Skepticism, and China-Focused Concerns

Although the main online narratives surrounding the war in Iran are led by Chinese media outlets (mainly CCTV, Xinhua, and China News Service), a lot is happening in the comment sections of state media social posts.

I find three things particularly noteworthy about these comment sections in general:

📌 There is room for relatively open discussion, but within a geopolitical frame

There is room for discussion. For many major international events, especially when China itself is involved, comment sections are often limited or completely closed. Content surrounding the Iranian conflict, however, has become one of the biggest drivers of engagement on Chinese social media in recent days.

In the past, some Iran-related news was heavily censored in China. For example, in 2022, the death of Mahsa Amini—the young woman who died after being detained and beaten by Tehran police for not properly wearing a hijab—made international headlines. The incident sparked outrage and protests worldwide. In China, however, coverage was limited, and there were no hashtags about Mahsa Amini on Chinese social media.

This time, reporting on developments in Iran focuses mainly on geopolitical aspects. By omitting certain grassroots elements (anti-regime demonstrations, pro-American sentiments), the Iranian war becomes less sensitive for China.

At the same time, the story is shaped and amplified in ways that reinforce Chinese narratives portraying the United States and Israel as irresponsible, unreliable aggressors driven by hegemony, while positioning China as a stable and trustworthy great power calling for peace in a multipolar world order.

📌 Netizens push back against state media narratives and are critical of Iran’s regime

Another noteworthy aspect is the overall tone of the comments. Especially in the first two days after the attacks began, I’ve seen far less overwhelming anti-Americanism than one might expect. Compared to other major international news moments, such as the US military operation in Venezuela, there appears to be not only less overt anti-American sentiment but also more skepticism toward Chinese state media reporting on the war, with many comments going against state media narratives.

When initial reports confirmed Khamanei’s death and the Israeli military claimed it had also killed other top Iranian regime officials, state media emphasized official condemnation and mourning, yet waves of Douyin users responded with thumbs-up and applause emojis.

On Kuaishou, some highly upvoted comments under videos of missile attacks, such as the Minab schoolgirl airstrike, questioned the authenticity of the reported facts. Others simply concluded that “war is always cruel.”

Some social media users also called out the algorithms of these short video platforms (Douyin & Kuaishou) for excessively pushing and amplifying Iranian military claims. Some joked that if they believed what their feeds were showing them, not only had the USS Abraham Lincoln already been sunk by Iran, but the United States itself had already been destroyed.

Sarcastic Weibo post: “On Douyin, the USS Lincoln aircraft carrier is about to be sunk by Iran,” responding to fake viral war footage circulating on the platform..

Other videos posted by state media outlets, such as Beijing Times, showing Iranian state media footage of people mourning the death of Khamenei, received top comments such as: “Why cry? Stand up and revolt,” or “They must have hired these people to cry, right?”

Following reports on the death of former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, popular comments praised the US-Israeli intelligence system for its strength and efficiency, while also expressing surprise at the perceived fragility of Iran’s regime following the decapitation of its senior leadership.

The fact that public sentiment is not uniformly condemning the US—and that many comments openly push back against official narratives—does not necessarily indicate a decline in anti-American sentiment on Chinese social media. Rather, it reflects clear negative sentiment toward the Iranian regime, making public responses to recent developments more complex and less monolithic than in previous international crises.

📌 Chinese netizens want to know what the Iran war means for China

Although official media reports and hashtags avoid focusing on how the Iranian conflict directly affects China, the war’s direct consequences are top of mind for netizens – not only do they want to know what it means for China, but also how it could affect them personally.

Perhaps as part of a broader simmering economic anxiety, people immediately began discussing commodity prices and personal financial planning after the attacks were reported.

Besides oil prices and crypto crashes, there’s been a special focus on gold buying. China is seeing a “gold rush” among Chinese consumers. Gold jewelry prices (金饰克价) have soared to 1,600 yuan (US$232) per gram, a historic milestone widely discussed on Chinese social media. Silver and crude oil prices have also risen sharply, while the cryptocurrency market has suffered a major decline, much to the dismay of those who admitted they had just invested.

In response to a video posted on Douyin by Chinese journalist Li Rui (李睿) showing Iranians weeping over Khamenei’s death, people in the comment sections joked:

💬 “I’m also weeping. My gold investment hadn’t recovered yet, and now I’ve lost money on it all over again 😭😭😭” (9300+likes)

💬 “I’m crying more. I just bought oil😭”

💬 “I also wanna cry. I just went all in on tech stocks on Friday.”

Footage shared by journalist Li Rui on Douyin showing Iranians mourning the loss of their Supreme Leader, while many reactions joked that they were also weeping due to rising prices and dropping stocks. Some even joked they found the carpet pretty, and where to get it.

Another popular talking point in this context is energy vulnerability and how the Iranian military locked down the Strait of Hormuz, a critical chokepoint for global energy.

The Strait of Hormuz is important to China because of its reliance on energy imports. In 2025, over 80% of Iran’s shipped oil went to China. Although this represents only about 13.4% of China’s total oil imports, China’s dependence on imported crude oil exceeds 70%, and roughly 40% of its total oil imports pass through Hormuz.

One widely shared Sina Finance article by “Wangye Talks Finance” (王爷说财经讯) predicted “severe turbulence” for the global energy market, leading to dramatic price jumps, not just in China’s domestic fuel windows, but also in driving costs and logistics, adding that “even courier fees and vegetable prices may climb.”

Other sources (Phoenix News, now offline) also covered other risks of supply disruptions, including how the war affects China’s chemical industry. (Iran is the world’s second-largest methanol producer, and over 60% of China’s methanol imports reportedly come from Iran.)

At the same time, there are also voices (such as blogger 枫冷慕诗, with 640k+ followers) who argue that Iran is not nearly as important to China as many believe, and that its role is often overestimated while its relationship with China is misunderstood.

Pointing to Iran’s inconsistent foreign policy, its relative weakness, and China’s limited economic ties with Iran (as well as its diversified energy imports), they argue that China likely anticipated the conflict and would not suffer catastrophic damage, even under the most extreme circumstances.

● Competing Narratives Among China’s Online Commentators

The complexity of US–Israeli military operations in Iran—and what they could mean for China and the rest of the world—is also reflected in the responses of China’s online key opinion leaders (KOLs). Rather than presenting a single narrative, many prominent commentators have offered sharply differing interpretations of the conflict, at times sparking heated debates among their followers.

🗣️ “The only one who can beat Hu Xijin is the Hu Xijin of the next day”

▪️Hu Xijin (胡锡进, former Global Times editor-in-chief, 24.9 million followers) immediately took to Weibo after the first reports came out about strikes on Iran. In one post, he called it “Iran’s tragedy” (“伊朗的悲剧”) that its people have to pay a heavy price for ambitions that exceed its actual strength and for confronting powers much greater than itself. He also proposed that it would be better for Israel to “move to Mars to find a place of peace there,” as the nation is “bound to fight one party after the other in the Middle East.”

But his focus shifted with the news of Khamenei’s death, moving from military escalation to the possible political outcomes in Iran. He described it as a historic turning point and leadership transition that could push the country either toward a harder anti-US/anti-Israel stance to preserve regime unity and deter domestic revolt, or toward a more conciliatory, American-friendly approach.

At the same time, Hu became a target of online jokes. When the first rumors of Khamenei’s death surfaced, he suggested the Iranian leader was probably keeping a low profile and preparing a public address that would be a major blow to the US and Israel, only to acknowledge the next day that Khamenei had indeed died. Later, Hu predicted that Iran’s new leader would be swiftly elected. As none of his predictions seem to be aging well, some netizens joked: “The only one who can beat Hu Xijin is the Hu Xijin of the next day” (“能打败胡锡进的是第二天的胡锡进”).

🗣️ “This is warfare with warmth and humanity, a new realm of the art of war”

▪️Zhu Zhiyong (朱智勇, blogger / formerly an author at the now-defunct China Elections and Governance academic website, 中国选举与治理, 210k followers) also shared a controversial opinion on March 1. He initially suggested that “Iran has taken the wrong path and made the wrong choices, it’s time to correct course,” and then praised the US-Israeli strategy.

💬 “Khamenei was precisely targeted and killed. Israel and the United States are writing a new era in the history of warfare: targeted elimination with minimal civilian and military casualties – this is warfare with warmth and humanity, a new realm of the art of war.”

The framing drew sharp pushback in comments from users who pointed to the bombing of the elementary school and called Zhu’s comments a rationalization of political assassination under international law.

His comments seem to have been deleted at the time of writing.

🗣️ “Iran should concentrate more missiles on striking Israel”

Other key opinion leaders and influencers took a completely different stance. Instead of praising the US and Israel, they praised Iranian counterattacks and promoted anti-American and anti-Israeli aggression.

▪️Sima Pinbang (司马平邦, military blogger, 7 million followers) suggested that Iran should focus more on missiles aimed specifically at Israel, and speculated that confiscated Starlink (星链) devices could give Iran a more useful targeting capability.

▪️Korolev (科罗廖夫, military affairs blogger, 6 million followers) made a bold post suggesting that Iran had only “one single move” left to counter both America and Israel, which would be a full-blown attack on Israel’s city centers, writing:

💬 “Iran should (..) exhaust all means to strike Israel’s population centers and civilian infrastructure. It should strike airports, fuel depots, electric power plants, transportation hubs, and communications centers..”

🗣️ “Iran’s counterattack against the US and Israel is something that will rewrite global military history”

▪️Luosifen Ge (螺蛳粉哥, a commentary account with 330k followers) shared another popular thread, where he suggested that Iran’s ability to bypass Israeli missile defenses reveals their weakness and serves as a lesson for China on the shortcomings of US/Israel military power.

💬 “The harder Iran’s missiles strike, the more the United States fears the nation-destroying capabilities of China and Russia. Many people have not realized that Iran’s counterattack against the US and Israel is an event that will rewrite global military history. (..) The reason is that Iran’s strikes represent the largest-scale missile war in human history, and also the first comprehensive real-combat stress test of modern strategic and tactical air-defense systems. (..) Iran used more than one hundred missiles to give the world a very real lesson. After this lesson, one conclusion is clear: the US homeland is no longer truly secure in the face of China and Russia.”

● The Armchair Generals and Women’s Rights Defenders on Chinese Social Media

While official media outlets are shaping China’s online discourse in response to developments in Iran, and key opinion leaders are sharing their views on the future of the conflict, there are also large numbers of commentators who focus on specific and often polarized views of the war in Iran.

⚔️ China’s online army of military strategists

Chinese social media users like the aforementioned “Luosifen Ge” are part of a large group of nationalist commentators with a specific interest in military affairs, who believe they know the best strategies for handling the war. We’ve seen them in action before, such as during the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war and in the years afterward.

Now, these supposed “military strategists” (军师们) have appeared in various online discussions, such as in the comment section under the Douyin account of the Iranian Embassy in China, sharing detailed plans and strategic outlines for how Iran should build defense lines, strike civilian infrastructure, and eliminate its enemies.

Some commenters even went so far as to list the names and exact coordinates of major Israeli desalination plants, concluding: “Don’t stop, attack until the coast.” Others listed multiple US bases in Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, the UAE, Iraq, and Syria, including geolocations and troop numbers, and described their strategic functions.

These “armchair generals” seem to use the conflict as a way to fulfill militaristic fantasies while also showing Chinese nationalist feelings.

They are the ones who want Iran to retaliate against America for Chinese gains. Maybe because they believe that if Iran collapses, China loses a key strategic buffer in the broader Middle East, or because they see Iran as a counterweight to challenge US dominance. Or perhaps because they view Iran as a prime military learning example for China, especially given that its main vulnerability is said to be not just military capacity but also counterintelligence failures.

“The weak get beaten. I suggest we significantly increase military spending this year,” some wrote. Such messaging is also in part boosted by Chinese official military accounts, writing things like: “The law of the jungle still prevails across human history. The moment vigilance slackens, it may bring irreversible disaster upon the nation and the people.”

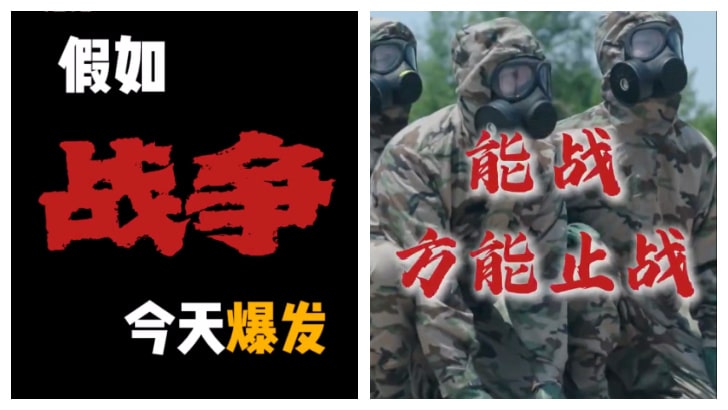

On Kuaishou, one of China’s official military accounts posted a video featuring Chinese armed forces, with the text reading, “Only by being able to fight can you stop war.” The video clearly conveyed that “if war breaks out today,” China is prepared for it.

Screenshots from the video posted by China’s military account on Kuaishou: “If war breaks out today, only those who are able to fight can stop it.”

China’s “armchair generals,” who are mostly found on Bilibili besides Douyin, show little empathy for ordinary Iranians. Instead, their discussions focus on military analysis, market watching, and a general sympathy for Iran as the party being attacked by the US and Israel — not for its people as potential beneficiaries of regime change.

⚔️ “A new era has begun”: Iran through a women’s rights lens

On the other end of the online spectrum, there’s a group of social media users whose voices have also become prominent over the past few days. They focus not on the military aspect but on women’s freedom, and are generally positive about the US-Israeli strikes as a possible liberation for Iranian women.

These days, one of the most-liked non-state-media posts on Weibo about Iran was a video shared by one Weibo user (光影总管) showing an Iranian woman crying tears of joy after hearing about the death of Khamenei, shouting: “Khamenei is dead! Finally! We are free! I can’t believe it!” It received at least 81,000 likes before being taken offline.

Many commenters expressed empathy for ordinary Iranians like her who lived under Khamenei’s theocratic rule, writing things like “Iranian women and children are [finally] seeing some light” (“伊朗女人,儿童看到光明了”) and: “In a country where women get killed for wearing the wrong headscarf, how could she not be glad?”

Examples of images shared by netizens: Iranian women in the 1970s, a meme about women in Islam being covered up, and a post with an AI image suggesting women in Iran lived under a regime that’s like a prison.

One Douyin user posted a photo showing women drinking beer and seemingly celebrating the death of the Iranian supreme leader, writing “Iranian girls tear off their face coverings and reveal their true faces, how beautiful.”

“A new era has begun,” others wrote, and some even called Khamenei’s death, which coincided with the end of the Spring Festival, the “first joy of the year” (“开年第一喜”).

Image posted on Douyin discussing Iranian women removing their headscarves and celebrating: ““Iranian girls tear off their face coverings and reveal their real faces.” (Original photo source unverified).

Others who expressed delight over the death of Khamenei called him “an enemy of civilization, the rule of law, openness, and progress,” and took this as an opportunity to remember Mahsa Amini.

Netease creator “Legal Classroom” (@法律学堂) expressed his hope that the death of the supreme leader represents a form of historical justice: “Today, the Iranian girl Mahsa Amini may finally be able to rest in peace.”

In comment sections, people cheer on women who celebrate a new beginning: “Iran, stand strong!”

One social media user (狮子头萌萌) wrote:

💬 “Iranian women are different, okay? They have always stood at the very front of resistance, whether during the struggle against the imperial monarchy back then, or later in opposition to the religious regime. The mistake they made was believing that religion and modern democracy could coexist.”

Meanwhile, there are also voices condemning these sentiments. One well-known nationalist account (@子午侠士) criticized a Chinese-speaking woman in Tehran who livestreamed, rejoicing during her broadcast. She said that because the United States and Israel launched a war against Iran, the political climate inside the country has changed. On the streets of Iran, fewer women are wearing headscarves, and Iranian women are moving toward greater freedom.

The Chinese blogger argued: “A headscarf does not represent everything, and the happiness of a people cannot be measured solely by whether they wear one,” and suggested the woman was an “anti-regime traitor.”

Those who disagree responded: “Did you go to Iran? Did you live there? Did you ask them? Do you know what they want?” Others echo this sentiment: “Go and ask Iranian women.”

Another commenter added: “There is nothing wrong with wanting to fight for freedom.”

Aside from detailed discussions regarding Iran, “armchair generals,” and women’s rights advocates, celebrity news continues as usual. Although the conflict in Iran remains a major topic, a juicy new scandal involving a popular Chinese singer has begun dominating headlines.

As the initial shock over the war in Iran subsides, it is becoming just another part of the daily news cycle. It now competes with Chinese celebrity gossip and is being shaped, reshaped, and contested in ways that, perhaps, reveal more about China’s online discourse than about the events in Iran themselves.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for her research contributions to this newsletter. Stay tuned for an overview of other trending news (including that juicy celebrity story) in our next edition.

Best,

Manya

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Two Sessions, a Celebrity Meltdown, and the Rise of China’s “Forget It” Mindset

Inside the Great Chinese Debate Over the Iran War

Spring Festival Trend Watch: Gala Highlights, Small-City Travel, and the Mazu Ritual Controversy

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive8 months ago

Chapter Dive8 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Arts & Entertainment5 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment5 months agoThe Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’