China Military

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

Published

2 minutes agoon

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China this week. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

In the last newsletter, I promised to follow up with more ‘post-parade’ responses. On Weibo and other social media platforms in China, hundreds of hashtags have emerged around the theme of the “afterglow after the parade” (阅兵后劲). In addition to the featured ‘AFP versus Xinhua’ discussion, here are some other noteworthy social media trends following the September 3 event, which turned out to be one of China’s largest military parades:

1 🇨🇳 “I’m So Happy in China”: Putin and Kim Jong-un’s Daughter in the Picture

Besides everything happening on Tiananmen Square during the parade, many netizens were just as interested—if not more—in what was going on at the sidelines. The presence of Putin and Kim Jong-un drew a lot of attention, and since political discussions are highly controlled on Chinese social media—especially during such high-profile events—online conversations mostly focused on smaller, more personal details.

One viral clip posted by Ta Kung Wen Wei Media (大公文匯網, a pro-Beijing Hong Kong media outlet) showed Putin during his various visits to China, where he always seems to enjoy local delicacies. The video’s caption read: “You have no idea how happy I am in China!” (“我在中国的快乐谁懂啊?!”).

As for Kim Jong-un, his daughter Kim Ju Ae, who accompanied him on this trip to China, became the social media star of the day. Many netizens still remembered her from a few years ago, when she joined her father at a Pyongyang military banquet and a widely publicized military parade. At the time, she was believed to be around ten years old, and Chinese bloggers nicknamed the round-cheeked girl “Golden Chubby” (金胖子) and “Golden Fourth Fatty” (金四胖).

In 2023 versus 2025

Now, however, the little girl has grown into a young lady. Many praised her style and grace, calling her a “little princess” (小公主). The hashtag “Kim Jong-un brought his daughter” (#金正恩把女儿金主爱带来了#) garnered over 190 million views on Weibo.

2 🎥 An Unexpected Face at Military Parade: US Pawnshop Owner Evan Kail

The American Evan Kail, a former pawnshop owner from Minnesota, was among the more unexpected faces at the parade. He appeared to be a semi-official guest, not watching the parade from Tiananmen Square but instead joining hundreds of locals to view it via livestream at the Temple of Heaven, where he was surrounded by cameras and media—making his attendance part of the broader media circus surrounding the military parade (#埃文凯尔天坛观看阅兵直播#).

Kail first went trending in 2022, when he posted a video asking for help after coming across an old war photo album he believed contained rare and previously unseen images of the Nanjing Massacre. He eventually donated the album to China. Although the book reportedly turned out not to contain photos of Nanjing but rather of Shanghai (with some images likely being mass-produced souvenir photos—and the authenticity of the album not really being the focus here), Kail is still well respected in China for bringing international attention to the atrocities of Nanjing. He recently published a book in China, and his story has been widely promoted by Chinese state media outlets.

3🏅 Parade Soldiers’ Sunburn Tan Lines Praised as “Special Medals”

Some of the post-parade “afterglow” discussions on social media focused on videos showing soldiers returning from the September 3 parade. They were easily recognizable at train stations and airports by the stark sun lines on their faces—caused by long hours of outdoor training and marching while wearing helmets with chin straps (see videos).

The “special medal” sun lines

Netizens called the marks a “special medal” (特殊的勋章), and the clips of soldiers returning home with their sunburnt faces also added a more vulnerable and human touch to those perfect military formations.

4 🤐 Man Detained Over “Parade-Insulting Comments”

It wasn’t all roses online during the military parade—although most netizens probably wouldn’t have noticed due to strict censorship. Some people were punished for expressing online criticism. One 47-year-old man surnamed Meng (孟) from Hubei was turned into a warning for others and was detained after posting “insulting” comments about the September 3 military parade on a livestream on WeChat. Another man from Tianjin saw his Weibo page blocked after he suggested that watching the parade is a shallow or fake form of patriotism—and it’s highly likely he was not the only one.

5 🚀 Military Model Toys Boom 175% in Sales Following Parade

Another post-parade effect: China has seen a surge in consumer interest in military-themed toys, from fighter jets to missiles and tanks. Starting on September 3, the military model category on Chinese e-commerce platform JD.com reported a 175% increase in sales.

6 🪖 The Next Military Parade

Thought this was it? Not quite. Chinese media are already stirring anticipation for future military parades with the hashtag “Looking Forward to the Next Military Parade” (#期待下次阅兵了#). While nothing has been confirmed, the next likely milestone years for large-scale parades are 2027 (the People’s Liberation Army’s 100th anniversary) and 2029 (the 80th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China). To be continued…

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Media

China’s “AFP Filter” Meme: How Netizens Turned a Western Media Lens into Online Patriotism

Chinese netizens embraced a supposed “demonizing” Western gaze in AFP photos and made it their own.

Published

4 days agoon

September 10, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For a long time, Chinese netizens have criticized how photography of Chinese news events by Western outlets—from BBC and CNN to AFP—makes China look more gloomy or intimidating. During this year’s military parade, the so-called “AFP filter” once again became a hot topic—and perhaps not in the way you’d expect.

In the past week following the military parade, Chinese social media remained filled with discussions about the much-anticipated September 3 V-Day parade, a spectacle that had been hyped for weeks and watched by millions across the country.

That morning, Chinese leader Xi Jinping, accompanied by his wife Peng Liyuan, welcomed international guests on the red carpet. When Xi arrived at Tiananmen Square alongside Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, office phone calls across the country quieted, and school classes paused to tune in to one of China’s largest-ever military parades along Chang’an Avenue in Beijing, held to commemorate China’s victory over Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

As tanks rolled and jets thundered overhead, and state media outlets such as People’s Daily and Xinhua livestreamed the entire event, many different details—from what happened on Tiananmen Square to who attended, and what happened before and after, both online and offline—captured the attention of netizens.

Amid all the discussions online, one particularly hot conversation was about the visual coverage of the event, and focused on AFP (法新社), Agence France Press, the global news agency headquartered in Paris.

Typing “AFP” (法新社) into Weibo in the days after the parade pulled up a long list of hashtags:

- Has AFP released their shots yet?

- V-Day Parade through AFP’s lens

- AFP’s god-tier photo

- Did AFP show up for the parade?

The fixation may seem odd—why would Chinese netizens care so much about a French news agency?

Popular queries centered on AFP.

The story actually goes back to 2022.

In July of that year, on the anniversary of the Communist Party’s founding, one Weibo influencer (@Jokielicious) noted that while domestic photographers portrayed the celebrations as bright and triumphant, she personally preferred the darker, almost menacing image of Beijing captured by Western journalists. In her view, through their lens, China appeared more powerful—even a little terrifying.

The original post.

The post went viral. Soon, netizens began comparing more of China’s state media photos with those from Western outlets. One photo in particular stood out: Xinhua’s casual, cheerful shot of Chinese soldiers contrasted sharply with AFP’s cold, almost cinematic frame.

Same event, different vibe. Chinese social media users compared these photos of Xinhua (top) versus AFP (down). AFP photo shot by Fred Dufour.

Netizens joked that Xinhua had made the celebration look like the opening of a new hotel, while AFP had cast it as “the dawn of an empire.”

Gradually, what began as a dig at the bad aesthetics of state media turned into something else: a subtle shift in how Chinese netizens were rethinking their country’s international image.

Under the hashtag #ChinaThroughOthersLens (#老中他拍), netizens shared images of China as seen through the lenses of various Western media outlets.

This wasn’t the first time such talk had appeared. In the early days of the Chinese internet, people often spoke of the so-called “BBC filter.” The idea was that the BBC habitually put footage of China under a grayish filter, making its visuals give off a vibe of repression and doom, which many felt was at odds with the actual vibrancy on the ground. To them, it was proof that the West was bent on painting China as backward and gloomy.

These discussions have continued in recent years.

For example, on Weibo there were debates about a photo of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, shot by Peter Thomas for Reuters, and used in various Western media reports about Wuhan and Covid as early as 2021. The top image shows the photographer’s vantage point.

“Looks like a cockroach in the gutter,” one popular comment described it.

Top image by Chinese media, lower image by Peter Thomas/Reuters, and was used in various Western media reports about Wuhan and Covid since as early as 2021.

Another example is the alleged “smog filter” applied by Western media outlets to Beijing skies during the China visit of US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in 2024.

The alleged “smog filter” applied to Beijing skies during Blinken’s visit. Top image: Chinese media. Middle: BBC. Lower: Washington Post.

AFP, meanwhile, seemed to offer a different kind of ‘distortion.’

Netizens said AFP’s photos often had a low-saturation, high-contrast, solemn tone, with wide angles that made the scenes feel oppressive yet majestic. Over time, any photo with that look—whether taken by AFP or not—was dubbed the “AFP filter” (法新社滤镜).

AFP has clarified multiple times that many of the viral examples weren’t even theirs—or that they were, but had been altered with an extra dark filter. They also refuted claims that AFP had published a photo series of Chinese soldiers titled “Dawn of Empire” to discredit China’s army.

AFP refuted claims that their photos discredited the Chinese army.

Nevertheless, the “AFP filter” label stuck. It became shorthand for a Western gaze that cast China not as impoverished or broken—as some claimed the “BBC filter” did—but as formidable, like a looming supervillain.

One running joke summed it up neatly: domestic shots are the festive version; Western shots are the red-tyrant version. And increasingly, netizens admitted they preferred the latter, commenting that while AFP shots often emphasize red to suggest authoritarianism, they actually like the red and what it stands for.

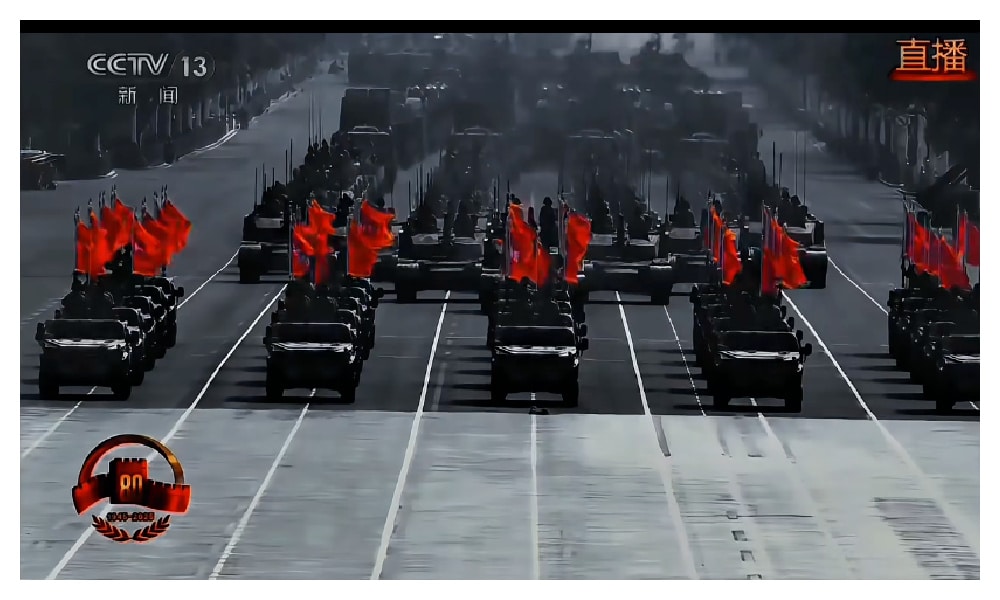

So, when this year’s V-Day came around, many were eager to see how AFP and other Western outlets would frame China as the dark, dangerous empire.

But when the photos dropped, the reaction was muted. They looked average. Some called them “disappointing.” “Where are the dark angles? Not doing it this time?” one blogger wondered. “Where’s the AFP hotline? I’d like to file a complaint!”

“Xinhua actually beat you this time,” some commented on AFP’s official Weibo account. Others agreed, putting the AFP photos and Xinhua photos side by side.

AFP photos on the left versus Xinhua photos on the right.

To make up for the letdown, people began editing the photos themselves—darkening the tones, adding dramatic shadows, and proudly labeling them with the tag “AFP filter” or calling it “The September 3rd Military Parade Through a AFP Lens” (法新社滤镜下的9.3阅兵). “Now that’s the right vibe,” they said: “I fixed it for you!”

Netizen @哔哔机 “AFP-fied” photos of the military parade by AFP.

Official media quickly picked up on the trend. Xinhua rolled out its own hashtags—#XinhuaAlwaysDeliversEpicShots (#新华社必出神图的决心#) and #XinhuaWins (#新华社秒了#)—and positioned itself as the true master of a new aesthetic narrative.

The message was clear: China no longer needs the Western gaze to frame itself as powerful or intimidating; it can do that on its own.

The “AFP v Xinhua” contest, the online movement to “AFP-ify” visuals, and the Chinese fandom around AFP’s moodier shots may have been wrapped in jokes and memes, but they also pointed to something deeper: the once “demonized” image of China that Western media pushed as threatening is now not only accepted by Chinese netizens, it’s embraced. Many have made it part of a confident, playful form of online patriotism, applauding the idea of being seen by the West as fearsome, even villainous, believing it amplifies China’s global authority.

As one netizen wrote: “I like it when we look like we crawl straight into their nightmares.”

Chinese journalist Kai Lei (@凯雷) suggested that these kinds of trends showed how the Chinese public plays an increasingly proactive role in shaping China’s global image.

By now, the AFP meme has become so strong that it doesn’t even require AFP anymore. Ultra-dramatic shots are simply called “AFP-level photos” (法新社级别).

For now, as many are enjoying the “afterglow” of the military parade, their appreciation for the AFP-style only seems to grow. As one Weibo user summed it up: “AFP tried to create a sense of oppression with dark, low-angle shots, but instead only strengthened the Chinese military’s aura of majesty.”

– By Ruixin Zhang and Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Military

The Final Countdown: China’s Military Parade on Social Media

The social media storylines behind China’s Victory Day parade.

Published

2 weeks agoon

September 2, 2025

🔥 A version of this column also appeared in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

The final hours of the final countdown to China’s Victory Day, commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, have begun. On Wednesday, September 3rd, China will hold what may be its largest-ever military parade, and the social media build-up to the spectacle has started weeks in advance.

The hashtag “Three Day Countdown to the 9.3 Military Parade” (#九三阅兵倒计时3天#) was top trending on Sunday, initiated by Beijing Daily (北京日报), and on Tuesday, Xinhua boosted the big 9.3 countdown hashtag (#九三阅兵倒计时#).

What can we expect? It will be a massive event. Even the empty Tiananmen Square in prep mode already looked impressive.

More than 10,000 troops, over 100 aircraft, and hundreds of pieces of ground equipment will appear in the 70-minute military parade, which will be attended by twenty-six foreign heads of state and government.

Over the past two weeks, I’ve been tracking the trending hashtags related to the parade. Starting from August 11 up to August 31, there have been about 225 different popular hashtags on Chinese social media (Weibo, Douyin, Kuaishou) related to the parade and its preparations.

According to official discourse, as stated by Major General Wu Zeke (吴泽棵) and described China Daily, the military parade is meant to reaffirm China’s commitment to “defending the victorious outcomes of World War II” and “contributing to world peace and development.”

But the hashtags tell a somewhat different story.

💬 A brief note on how hashtags are made, with a focus on Weibo: a hashtag is created by placing a topic between two # signs, which then turns it into a clickable link. In theory, anyone can initiate a hashtag, but in practice, almost all of the trending hashtags related to the parade—as a major political event—are initiated and promoted by officials channels and Chinese state media outlets such as the Communist Youth League, People’s Daily, Global Times, and CCTV Military (央视军事).

I say “almost” because, although the online narrative is largely shaped by official rhetoric, a few hashtags are instead launched by commercial accounts, such as Weibo Military Affairs (微博军事) or Sina Military (新浪军事).

I found that the narratives around the military parade can roughly be grouped into four broad themes:

🔸 Memory & Identity (WWII): V-Day as living heritage, reinforcing Party legitimacy and national identity. Use of wartime songs, veterans’ descendants, and “cross-time dialogues” to bind past sacrifice to present duty, with the “never forget” slogan reiterated everywhere.

🔸 Military Strength & Modernization: Centers on the PLA’s advanced tech and China’s military self-reliance: new weapons making their debut, 100% domestic “active main battle systems,” precision formations, and new PLA flags help build the image of China as a military powerhouse, romanticized by Chinese media.

🔸 Chinese Society (Youth & Women): The parade as a mass-participation event, weaving parade patriotism with everyday life across gender & generations. Focus on participation by China’s younger generations (00后), including viral slang to make it more appealing to youth, and clear attempt to make female honor-guard and militia especially visible.

🔸 China in the World: The parade is perhaps just as much—some say even more—about politics as it is about the military. The guest list is like a diplomatic barometer: attendance by leaders like Putin and Kim Jong-un (amid very few Western counterparts) is read as a signal of China’s global power vs the US.

The red thread through all of this is the power of the Chinese nation under the guidance of the Party.

#1: HISTORY: National Identity through Memory of WWII

Examples of trending hashtags:

- #中国人民抗战胜利80周年# 80th Anniversary of the Chinese People’s Victory in the War of Resistance

- #这段与先辈的跨时空对话看哭了# This Cross-Time Dialogue With Forefathers Made People Cry

- #烽火战歌# Songs of Fire and War

- #让战歌点燃我们的烽火记忆# Let War Songs Ignite Our Fiery Memories

- #九三阅兵这些旗帜将亮相# These Flags Will Be Unveiled at the 9/3 Military Parade

Memories of World War II—more specifically, the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), known in China as the War of Resistance Against Japan (抗日战争)—have occupied a central place in online narratives this summer. I wrote about this remembrance of war, particularly in Chinese cinemas, in the previous newsletter.

Of course, it is no surprise that a national V-Day event is about the history of war, but what is remembered and how this is done, managed by whom, says a lot about the present and the future.

Here, wartime memory serves as the foundation for Party legitimacy, national identity, and strength. Just as a tree is connected to its roots, the people are meant to remain connected to the history of war—a message that is continuously reiterated in Chinese media: “never forget, always remember.”

The connection between past and present is clarified through art, videos, and music. Wartime, anti-Japanese songs play a big role in the parade, and are also being revived in new settings, such as in a 10-part patriotic production released by CCTV ahead of the parade where these songs are performed by various artists in a historical stage performance that incorporates real WWII footage (watch on Youtube here).

This year, the “cross-time dialogue” (跨时空对话) video trend has also been promoted by official media, spreading (AI) videos imagining encounters where China’s wartime fighters meet modern-day soldiers, who then deliver the message to them that China won, setting their spirit “free” through the power of the new China (see videos).

There is an emphasis on wartime legacies and their continuity into the present military force.

One trending video shows a military training for the parade, with the troops shouting: “Never forget, never forget, never forget! It’s difficult? Think of the national humiliation. Tired? Think of our forefathers during the War of Resistance against Japan.”

The commander then says: “Exactly, this is why we hold military parades. It’s to remember history. Pay tribute to the martyrs. And especially, to carry forward the great spirit of the War of Resistance.”

Another trending topic focused on how the parade will, for the first time, feature new military flags. Under the leadership of the Party flag, national flag, and military flag, several new banners will make their debut, including flags for the PLA Cyberspace Force and the PLA Aerospace Force.

Not only is the debut of these flags symbolic, but so is the selection of their bearers: young, experienced soldiers with personal connections to the past. The Party flag bearer, Wang Zihao (王子赫), for example, is a descendant of WWII fighters. Chinese media have highlighted how he sees his role in the parade as a way to honor his family’s legacy—another example of the media’s emphasis on continuity and strength, grounded in the Party’s leadership.

#2: MILITARY: Showcasing China’s Strength and Modernization

Examples of trending hashtags:

- #揭秘九三阅兵装备# Unveiling the Equipment of the 9/3 Parade

- #九三阅兵首次亮新型装备占比很大# High Proportion of New Weapons Making Debut at the 9/3 Parade

- #天坛和战机同框震一幕# Stunning Scene of the Temple of Heaven and Fighter Jets in the Same Frame

- #所有受阅武器装备都是国产现役主战装备# All Parade Equipment To Be Domestic Active Main Battle Systems

- #中国战机一出现就是硬核浪漫# The Moment Chinese Fighter Jets Appear, It’s Hardcore Romance

- #中国战机披上晚霞金甲# Chinese Fighter Jets Donned in Golden Armor of Sunset Glow

The upcoming parade is not only an event to commemorate history, but also a showcase of the rapid modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Weibo is filled with clips and commentary about the new generation of high-tech weaponry set to appear—from the 191 automatic rifle and the 99A main battle tank to fighter jets, combat drones, and ballistic missiles.

But past-meets-present themes also run through the military displays. Traditional weapons are featured alongside modern equipment, and the connection to history is reinforced through visual imagery that’s propagated by official channels.

The Communist Youth League, for example, shared a video that showed the ancient Temple of Heaven and modern fighter jets captured together in a single frame.

The romanticization of China’s military strength is clear: fighter jets glowing in the dawn light, dazzling sky formations, and military choreography executed with perfect precision.

Beyond the visuals, there is also a strong emphasis on military hardware being 100% made in China—developed and produced domestically, and actively in use.

#3: SOCIETY: Patriotic Youth, Strong Women

Examples of trending hashtags:

- #想阅兵的心到达了顶峰# My Desire to Watch the Parade Has Hit a Peak

- #九三阅兵徒步方队最小队员只有17岁# Youngest Member of the 9/3 Parade Marching Unit Is Just 17

- #这就是又美又飒的中国仪仗女兵# These Are China’s Honor-Guard Women: Beautiful and Fierce

- #阅兵训练现场女民兵真飒# Women’s Militia at the Parade Training Base Are Truly “Sa” [Fierce]

- #仪仗女兵说誓做军中花木兰# Female Honor Guards Swear to Be the Mulan of the Army

Another thing that stands out in the official social media campaign surrounding the military parade is the effort by Chinese media to make the event appeal to a wider domestic audience, especially younger people, by highlighting elements that link the parade to everyday life and by featuring topics that speak to younger viewers.

One way this is done is through the use of internet slang and popular language, such as describing how “super hyped” everyone is for the parade (#九三阅兵期待值拉满#), or that watching China’s parade is “pure satisfaction” (#看中国阅兵一整个舒适了#).

There is also emphasis on how China’s youth play an important role in the V-Day events, with a high number of participants being post-2000s (#九三阅兵仪仗方队00后含量有点高#) and the youngest just 17 years old (#九三阅兵徒步方队最小队员只有17岁#).

The role of women is similarly spotlighted, with multiple stories focusing on the “heroic female militia” and the striking presence of female honor guards (仪仗女兵).

At the rehearsal grounds, one spokesperson of the female guards of honor declared the women swore to be like Hua Mulan for the army, referring to the legendary Chinese heroine who disguised herself as a man to fight for her family and country.

The phrase (#仪仗女兵说誓做军中花木兰#) went viral and drew widespread praise, though some commenters also questioned why the female honor guards wear skirts instead of trousers.

#4: CHINA IN THE WORLD: A Diplomatic Stage

Example of trending hashtags:

- #普京和金正恩等出席抗战纪念活动# Putin & Kim Jong-Un Will Attend V-Day Commemorations

- #解读九三阅兵出席嘉宾名单# Decoding the Guest List of the 9/3 Parade

- #外媒关注普京和金正恩出席九三阅兵# Foreign Media Focus on Putin and Kim Jong-un Attending the 9/3 Parade

- #鸠山由纪夫参加九三阅兵# Yukio Hatoyama Will Attend the 9/3 Parade

- #日本妄图给中国九三阅兵按下暂停键# Japan’s Futile Attempt to Hit Pause on China’s 9/3 Parade

- #日本呼吁各国别参加九三阅兵意欲何为# What Is Japan’s Intention in Urging Countries Not to Attend the 9/3 Parade

A major theme on Chinese social media regarding the military parade revolves around who will attend, and what message that attendance sends.

On August 28, it was announced that Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un are both among 26 foreign heads of state and government leaders expected to attend the military parade.

That Putin would attend the upcoming major parade is no surprise, but the presence of Kim Jong-un is more noteworthy—especially alongside leaders from Iran, Pakistan, Cuba, Nepal, Myanmar, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Cambodia, with a clear absence of leaders from Western countries.

The gathering of Xi, Putin, and Kim Jong-un in the heart of Beijing is seen not just as a commemorative event, but as a symbolic ‘win’ for China. One political commentator on Weibo noted it was a loss for Washington, pointing out that Trump recently expressed his wish to meet Kim, while US–Russia efforts to end the war in Ukraine have yielded little progress. The September 3 attendance of these leaders underscores China’s shifting and expanding role on the global stage, as well as its alliances in an increasingly tense geopolitical climate.

On August 31, the Taipei Times published a piece about a symposium hosted by the Foundation on Asia-Pacific Peace Studies in Taipei, where several experts and academics discussed the meaning of the upcoming parade.

Steve Yates, former US deputy national security adviser, described the parade as ‘more political than military.’

Chang Kuo-Cheng (張國城), professor of international relations at Taipei Medical University, called it a ‘governance capability competition’ between China and the US, adding that the guest list is meant to signal that China, Russia, and North Korea stand united in the East against NATO.

Tung Li-wen (董立文), executive director of Asia-Pacific Studies, argued that the real highlight of the military parade is not the weapons, but who is invited to watch.

While the foreign guest list serves as a diplomatic barometer, the numerous press briefings, rehearsal videos, and multilingual livestreams highlight how the parade is staged as a global spectacle; a carefully choreographed show of Chinese power.

As the countdown to the September 3 parade reaches its final days, it is becoming clear that the spectacle serves multiple purposes. While the official narrative stresses its role as a tribute to global peace, the parade is just as much about projecting China’s unity and strength — and about Xi Jinping’s ultimate authority over the PLA — at a time of domestic economic stagnation and an unpredictable, turbulent international environment.

💬 In terms of hashtags, the military-themed ones are the most dominant on social media (about 60% of posts, by my count), followed by those stressing the parade’s international significance (18%), with more historical and social themes lagging behind. Still, who knows — the military parade could yet feature some surprise elements, which also wouldn’t surprise me.

Also want to watch the parade? There will be multiple broadcasts and livestreams available on Wednesday (for example, CCTV directly). The parade is expected to start at 10:00 AM 9AM Beijing time — though it might be worth tuning in earlier.

Will be watching closely, and I’ll share some key highlights once the parade concludes.

Best,

Manya

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

China’s “AFP Filter” Meme: How Netizens Turned a Western Media Lens into Online Patriotism

The Final Countdown: China’s Military Parade on Social Media

How Female Comedians Are Shaping China’s Stand-Up Boom

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral2 months ago

China Memes & Viral2 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature11 months ago

China Books & Literature11 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Society12 months ago

China Society12 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China Insight4 months ago

China Insight4 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal