China History

Did This TikToker Find Unseen Nanjing Massacre Photos? Regardless, Chinese Netizens Want the World to Know about 1937

Although it is yet unclear if the photos are authentic, Chinese netizens just want the world to know more about the Nanjing Massacre.

Published

2 years agoon

Did an American pawn shop owner find unseen photos of the Nanjing Massacre? As his Tiktok video is going viral online, Chinese netizens are shocked to find how little Western social media users know about what happened during the Japanese invasion of Nanjing in 1937. They hope the video helps strengthen international awareness on the ‘Rape of Nanjing’.

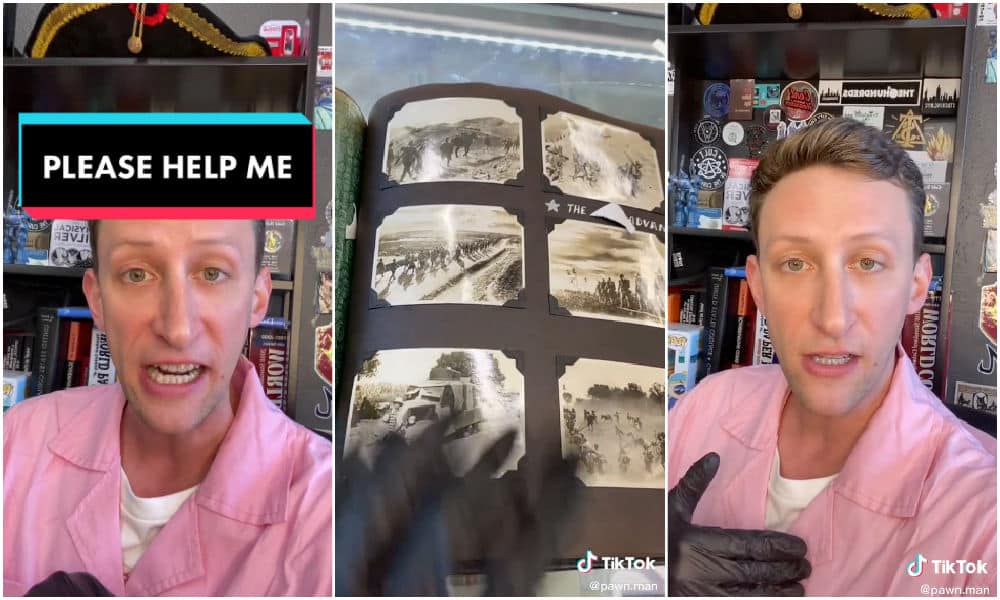

Over the past week, an American TikTok video has attracted the attention of Chinese netizens. On September 1st, Minnesota pawn shop owner Evan Kail, who runs the Pawn Master Kail (@pawn.man) Tiktok account, turned to his followers and asked for help in a video after coming across an old photo book that he believed contained extremely rare and unseen photos of the Nanjing Massacre.

Kail also posted some of the photos from the book on his Twitter account (viewer discretion advised).

Some photos from the tiktok about the Rape of Nanjing that I could not publish on that platform — pic.twitter.com/ew7mAmq6cz

— Evan Kail (PAWN MAN) (@EvanKail) September 1, 2022

The so-called Nanjing or Nanking Massacre (南京大屠杀, also known as the ‘Rape of Nanjing’) happened during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) – which became part of WWII in 1941 after Pearl Harbor – and refers to the mass murder of Chinese civilians by Japanese invaders during a six-week period from December 13, 1937, to January 1938.

According to China’s official data, at least 300,000 residents, including children and elderly, lost their lives during the massacre that became the most notorious Japanese atrocity of the Second Sino-Japanese War. In October 2015, UNESCO added Nanjing Massacre historical documents to its Memory of the World Register.

In his September 1st video, the pawn shop owner Evan Kails says: “This is the most disturbing thing I’ve ever seen in my career and I desperately need your help (..) Had a customer reach out and they told me they had this old book of photos from WWII. It’s been in their family for a while and they wanted me to try and sell it.”

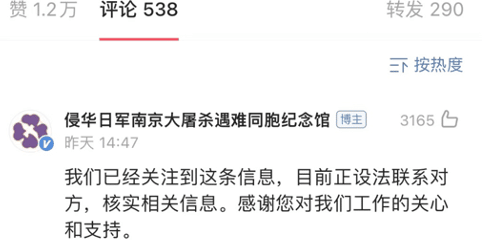

Kail then explains the book is by a soldier who was stationed in South East Asia around 1937-1938 and who allegedly photographed life in China and other countries. The album includes a series of war-related images that Kail claims are too shocking to share with his followers (“worse than anything I have seen on the Internet”) and which he believes were taken during the Japanese invasion of Nanjing in 1937.

The pawn shop owner said he believes that these photos “need to be seen, documented, and preserved” and asked his followers to share his video as widely as possible, hoping that the appropriate channels, such as museums, could contact him.

Shortly after, Kail’s video was also shared on Chinese social media. The U.S.-based Weibo user RuruRin, who has more than one million followers, posted the video on Thursday afternoon with Chinese subtitles, after which it quickly became a top trending topic on Weibo.

Many Chinese social media users mentioned and tagged the official Weibo account of The Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders, which is a Nanjing-based museum to memorialize those who were killed in the Nanjing Massacre. About three hours later, the official Weibo account of the museum responded and stated that they had seen the post, and had attempted to contact Kail to verify the information.

The Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum responds on Weibo, thanking everyone for alerting them and saying they are attempting to get in touch with Kail.

The video shared by RuruRin so far has received nearly 300,000 likes and thousand of comments on Weibo. The hashtag “Foreign netizen May Have Discovered Color Photos of the Nanjing Massacre” (#国外网友或发现南京大屠杀彩照#) appeared on the trending list of Weibo and climbed to the second position by late night of September 1. By Sunday, it had received over 960 million clicks.

While there is still doubt regarding the authenticity of the photos, many Chinese Weibo users suggest that if the photos are authentic, the Chinese government should purchase them regardless of the cost because it will provide additional evidence to counter Japan’s denial of this history.

Some are concerned that this book will be sold to a Japanese buyer, while others are worried about Kail’s personal safety after his discovery, given that Iris Chang, author of renowned The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II, received frequent harassment and threats from some Japanese after her book was published in 1997. Chang committed suicide in 2004 at the age of 36.

One of the issues that has become a big part of Chinese online discussions regarding the Pawn Master video is how many Americans and other foreigners are not aware of the history of what happened in Nanjing. Weibo user RuruRin dedicated a post to this issue, sharing many Tiktok comments from people writing they had never even heard about the Nanjing Massacre.

“Regardless of how this story turns out,” Rururin wrote: “It is gratifying to know because of this photo album video, millions of people have now become aware of the existence of the Nanjing Massacre, and many are willing to learn more about it because of this video. Most American schools do not teach this history, so while basically everyone in the U.S. knows about the Holocaust, few people know about the Nanjing Massacre.”

China has done a lot to create more awareness about what happened in Nanjing. Besides the countless books, movies, documentaries, and TV series dedicated to the topic, China also introduced the “National Memorial Day for the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre” in 2014. It is an annual memorial day on December 13, which is the day the imperial Japanese army invaded Nanjing.

An important site where visitors are educated about this painful history is the Memorial Hall of the Nanjing Massacre which was opened on August 15, 1985. This official memorial museum is built near the site of the “pit of ten thousand corpses” where thousands of bodies were buried during the killings. The Memorial Hall covers a total area of 103,000 square meters is home to important historical records, victim testimonies, artifacts, and photographs.

“When it’s about the Nanjing Massacre, we are never short of evidence – we are short of international attention for it.”

Despite all the stories and evidence on record, there are many people across the world who have no knowledge of this Nanjing history. One Weibo user wrote: “When it’s about the [Nanjing Massacre] history, we are never short of evidence – we are short of international attention for it.”

Renowned Chinese director and actor Jiang Wen (姜文) previously commented on this lack of international attention for the Nanjing Massacre. In 2018, he was asked why he chose 1937 as the background setting for his movie Hidden Man. Jiang replied that he wanted to use the film to “let the world know what the Japanese did” and said:

“China in 1937 faced a broken country and millions of ruined families. The entire Chinese population stood up to resist the invaders. The theme of resisting invaders should be expressed all over the world. On this aspect, China doesn’t do it as well as the West. The reason why Chinese people now know that the Nazis were bad, and the Jews were persecuted, is because Western artists and investors work hard every year to make sure that a young person growing up in China, even if they’re from a small town, will know what kind of things the Nazis did. However, the majority of the world is unaware of what the Japanese did.”

Regarding Evan Kail’s discovery and Tiktok video, many Chinese netizens seem to care less about the photos being authentic but more about how the photos and the video increase international historical awareness about the Nanjing Massacre.

In a follow-up video, Kail told that his phone had been ringing non-stop since the video and that his story was featured in, among others, Rolling Stone and Newsweek. Kail also shared that the photo book owner agreed that only a museum would be getting the photo book.

Kail claimed that he had been in touch with Chinese officials regarding the book, but that he felt he was facing a “dilemma” because he did not want the photo album to be used for a certain “political agenda” where only some of the photos would be selected with others disregarded. “There are so many histories in this book,” Kail said: “It has to be properly treasured.”

Meanwhile, on Twitter, there are multiple people involved in helping in the process of authenticating this photo album. The popular ‘Fake History Hunter’ account claims the album is genuine as a souvenir album countless sailors bought when their tour of duty was about to begin, but that some of the photos in the album are not unique and can also be found online.

This video has gone viral on tiktok, man finds album that he thinks may have extremely rare and unusual photos of the Nanjing (Nanking) massacre.

But things are not like they seem, I'll explain in the following tweets. 🧵https://t.co/8bnhv9AuM0— Fake History Hunter (@fakehistoryhunt) September 1, 2022

On Weibo as well, there are some convincing expert bloggers who claim they have come across similar photo albums and that the person who it belonged to had not necessarily been to Nanjing (#国内博主称有相似南京大屠杀彩照相册#).

Chinese blogger shares that he has a similar photo album.

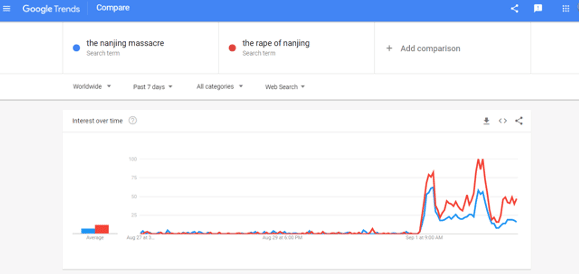

Where will this old photo book eventually end up? That is still unclear. Regardless, Kail is pleased that the video educated more people about this war history, while Weibo netizens are glad that more people outside of China have started to look up information regarding the ‘Nanjing Massacre’ to learn more about what happened there.

Google trends shows, starting from Sep 1, the worldwide search volume of the term “the Nanjing Massacre” went up suddenly.

“Actually I don’t think it really matters whether the color photos are genuine or not, there’s is enough evidence of the Nanjing Massacre,” one Weibo user (@不知江月V) writes: “But a positive effect of this incident is how it went viral and led foreign netizens to take the initiative to learn and understand the history of the Nanjing Massacre. The classroom WWII history in foreign countries is basically limited to the German military and there is not much explanation of the atrocities committed by the Japanese in Asia. So this has achieved the goal of foreign netizens knowing and understanding more about the blood debt owed by the Japanese to the Chinese people.”

By Wendy Huang, with contributions by Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Wendy Huang is a China-based Beijing Language and Culture University graduate who currently works for a Public Relations & Media software company. She believes that, despite the many obstacles, Chinese social media sites such as Weibo can help Chinese internet users to become more informed and open-minded regarding various social issues in present-day China.

China History

A Chinese Christmas Message: It’s Not Santa Bringing Peace, but the People’s Liberation Army

On social media, Chinese official channels are not celebrating a Merry Christmas but instead focus on a Military Christmas.

Published

7 months agoon

December 26, 2023

It is not Santa bringing you peace and joy, it is the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Chinese state media and other influential social media accounts have been pushing an alternative Christmas narrative this year, which makes it very clear that this ‘Merry Christmas’ is brought by China’s military forces, not by a Western legendary figure.

On December 24, Party newspaper People’s Daily published a video on Weibo featuring various young PLA soldiers, writing:

“Thank you for your hard work! Thanks to their protection, we have a peaceful Christmas Eve. They come from all over the country, steadfastly guarding the front lines day and night. “With our youth, we defend our prosperous China!” Thank you, and salute!”

People’s Daily post on Weibo, December 24 2023.

The main argument that is propagated, is that this time in China should not be about Christmas and Santa Claus, but about remembering the end of the Korean War and paying tribute to China’s soldiers.

This narrative is not just promoted on social media by Chinese official media channels, it is also propagated in various other ways.

One Weibo user shared a photo of a mall in Binzhou where big banners were hanging reminding people of the 73rd anniversary of the Battle of Chosin Reservoir during the Korean War: “December 24 is not about Christmas Eve, but about the victory at Chosin Reservoir.”

Mall banners reminding Chinese that December 24 is about commemorating the end of the Second Phase Offensive (photo taken at 滨州吾悦广场/posted by 武汉潘唯杰).

Another blogger posted a video showing LED signs on taxis, allegedly in the Hinggan League in Inner Mongolia, with the words: “December 24 is NOT Christmas Eve, it is the military victory of the Battle of Chosin Reservoir” (“12.24不是平安夜,是长津湖战役胜利日”).

Chinese taxis with a message: December 24 is NOT "Christmas Eve" but a day to commemorate the Chinese victory during the Second Phase Offensive of the Korean War in 1950. It's not a Merry Christmas but a military one. Video posted on Weibo, allegedly recorded in Inner Mongolia. pic.twitter.com/XZlRTinmXr

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) December 26, 2023

One social media video showed a teacher at a middle school in Chongqing also emphasizing to her students that “it’s not Father Christmas who brings us a happy and peaceful life, but our young soldiers!”

In the context of the Korean War (1950-1953), December 24 marks the conclusion of the Second Phase Offensive (1950), which was launched by the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army against the United Nations Command forces–primarily U.S. and South Korean troops.

The Chinese divisions’ surprise attack countered the ‘Home-by-Christmas’ campaign. This name stemmed from the UN forces’ belief that they would soon prevail, end the conflict, and be home well in time to celebrate Christmas. Instead, they were forced into retreat and the Chinese reclaimed most of North Korea by December 24, 1950.

The Battle of the Chosin Reservoir, also known as the the Battle at Lake Changjin, is part of this history. The battle began on November 27 of 1950, five months after the start of the Korean War. The 2021 movie Changjin Lake (长津湖/The Battle at Lake Changjin) provides a Chinese perspective on the lead-up and unfolding of this massive ground attack of the Chinese 9th Army Group, in which thousands of soldiers died.

Especially in recent years and in light of the launch of the blockbuster movie, there is an increased focus on the Chinese attack at Chosin as a glorious victory and strategic success for turning around the war situation in Korea and defending its own borders, underscoring the military strength of the People’s Republic of China as a new force to be reckoned with (read more here).

This Chinese Christmas narrative of honoring the PLA coincides with a series of popular social media posts from bloggers facing criticism for celebrating Christmas in China.

One of them is Liu Xiaoguang (刘晓光 @_恶魔奶爸_, 1.7 million followers), who wrote on December 25:

“Some people are criticizing me for celebrating Christmas Eve, because, by celebrating a foreign festival, I would be unpatriotic and forgetful of our martyrs. What can I say, in our family Christmas must be a big deal, even if I don’t come home it must be celebrated, because my mom is a Christian, and she’s very devout (..) So you see, on one hand I should promote traditional Chinese virtues, and show filial piety, on the other hand I should be patriotic and not celebrate foreign festivals.”

Meanwhile, other popular bloggers stress the importance of remembering China’s military heroes during this time. Influential media blogger Zhang Xiaolei (@晓磊) posted: “It’s not Santa Claus who gives you peace, it’s the Chinese soldiers! #ChristmasEve” (“给你平安的不是圣诞老人,而是中国军人!🙏#平安夜#”). With his post, he added various pictures showing Chinese soldiers frozen in the snow as also depicted in the Battle at Lake Changjin movie.

Throughout the years, Christmas has become more popular in China, but as a predominantly atheist country with a small proportion of Christians, the festival is more about the commercial side of the holiday season including shopping and promotions, decorations, entertainment, etc.

Nevertheless, Christmas in China is generally perceived as “a foreign” or “Western” festival, and there have been consistent concerns that the festivities associated with Christmas clash with traditional Chinese culture.

In the past, these concerns have led to actual bans on Christmas celebrations. For instance, in 2017, officials in Hengyang were instructed not to partake in Christmas festivities and several universities throughout China have previously cautioned students against engaging in Christmas-related activities.

Chinese political and social commentator Hu Xijin (@胡锡进) also weighed in on the issue. In his December 24 social media column, the former Global Times editor-in-chief wrote that there is no problem with Christmas Eve and the Second Phase Offensive victory day both receiving attention on the same day. Even if the younger generations in China view Christmas more as a commercial event rather than a religious one, it’s understandable for businesses to capitalize on this period for additional revenue. He wrote:

“In this era of globalization, holiday cultures inevitably influence each other. The Chinese government does not actively promote the rise of “Western holidays” for its own reasons, but they also have no intention to “suppress foreign holidays.” Some Chinese celebrate “Western holidays” and it is their right to do, they should not face criticism for it.”

Although many Chinese netizens post different viewpoints on this year’s Christmas debate, there are some who just don’t understand what all the fuss is about. “December 24 can be both Christmas Eve, and it can be Victory Day. It’s not like we need to pick one over the other. We are free to choose whatever.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Backgrounder

“Oppenheimer” in China: Highlighting the Story of Qian Xuesen

Qian Xuesen is a renowned Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s.

Published

10 months agoon

September 16, 2023By

Zilan Qian

They shared the same campus, lived in the same era, and both played pivotal roles in shaping modern history while navigating the intricate interplay between science and politics. With the release of the “Oppenheimer” movie in China, the renowned Chinese scientist Qian Xuesen is being compared to the American J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In late August, the highly anticipated U.S. movie Oppenheimer finally premiered in China, shedding light on the life of the famous American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967).

Besides igniting discussions about the life of this prominent scientist, the film has also reignited domestic media and public interest in Chinese scientists connected to Oppenheimer and nuclear physics.

There is one Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s. This is aerospace engineer and cyberneticist Qian Xuesen (钱学森, 1911-2009). Like Oppenheimer, he pursued his postgraduate studies overseas, taught at Caltech, and played a pivotal role during World War II for the US.

Qian Xuesen is so widely recognized in China that whenever I introduce myself there, I often clarify my last name by saying, “it’s the same Qian as Qian Xuesen’s,” to ensure that people get my name.

Some Chinese blogs recently compared the academic paths and scholarly contributions of the two scientists, while others highlighted the similarities in their political challenges, including the revocation of their security clearances.

The era of McCarthyism in the United States cast a shadow over Qian’s career, and, similar to Oppenheimer, he was branded as a “communist suspect.” Eventually, these political pressures forced him to return to China.

Although Qian’s return to China made his later life different from Oppenheimer’s, both scientists lived their lives navigating the complex dynamics between science and politics. Here, we provide a brief overview of the life and accomplishments of Qian Xuesen.

Departing: Going to America

Qian Xuesen (钱学森, also written as Hsue-Shen Tsien), often referred to as the “father of China’s missile and space program,” was born in Shanghai in 1911,1 a pivotal year marked by a historic revolution that brought an end to the imperial dynasty and gave rise to the Republic of China.

Much like Oppenheimer, who pursued further studies at Cambridge after completing his undergraduate education, Qian embarked on a journey to the United States following his bachelor’s studies at National Chiao Tung University (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University). He spent a year at Tsinghua University in preparation for his departure.

The year was 1935, during the eighth year of the Chinese Civil War and the fourth year of Japan’s invasion of China, setting the backdrop for his academic pursuits in a turbulent era.

Qian in his office at Caltech (image source).

One year after arriving in the U.S., Qian earned his master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Three years later, in 1939, the 27-year-old Qian Xuesen completed his PhD at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the very institution where Oppenheimer had been welcomed in 1927. In 1943, Qian solidified his position in academia as an associate professor at Caltech. While at Caltech, Qian helped found NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

When World War II began, while Oppenheimer was overseeing the Manhattan Project’s efforts to assist the U.S. in developing the atomic bomb, Qian actively supported the U.S. government. He served on the U.S. government’s Scientific Advisory Board and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel.

The first meeting of the US Department of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board in 1946. The predecessor, the Scientific Advisory Group, was founded in 1944 to evaluate the aeronautical programs and facilities of the Axis powers of World War II. Qian can be seen standing in the back, the second on the left (image source).

After the war, Qian went to teach at MIT and returned to Caltech as a full-time professor in 1949. During that same year, Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Just one year later, the newly-formed nation became involved in the Korean War, and China fought a bloody battle against the United States.

Red Scare: Being Labeled as a Communist

Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen both had an interest in Communism even prior to World War II, attending communist gatherings and showing sympathy towards the Communist cause.

Qian and Oppenheimer may have briefly met each other through their shared involvement in communist activities. During his time at Caltech, Qian secretly attended meetings with Frank Oppenheimer, the brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Monk 2013).

However, it was only after the war that their political leanings became a focal point for the FBI.

Just as the FBI accused Oppenheimer of being an agent of the Soviet Union, they quickly labeled Qian as a subversive communist, largely due to his Chinese heritage. While the government did not succeed in proving that Qian had communist ties with China during that period, they did ultimately succeed in portraying Qian as a communist affiliated with China a decade later.

During the transition from the 1940s to the 1950s, the Cold War was underway, and the anti-communist witch-hunts associated with the McCarthy era started to intensify (BBC 2020).

In 1950, the Korean War erupted, with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) joining North Korea in the conflict against South Korea, which received support from the United States. It was during this tumultuous period that the FBI officially accused Qian of communist sympathies in 1950, leading to the revocation of his security clearance despite objections from Qian’s colleagues. Four years later, in 1954, Robert Oppenheimer went through a similar process.

The 1950’s security hearing of Qian (second left). (Image source).

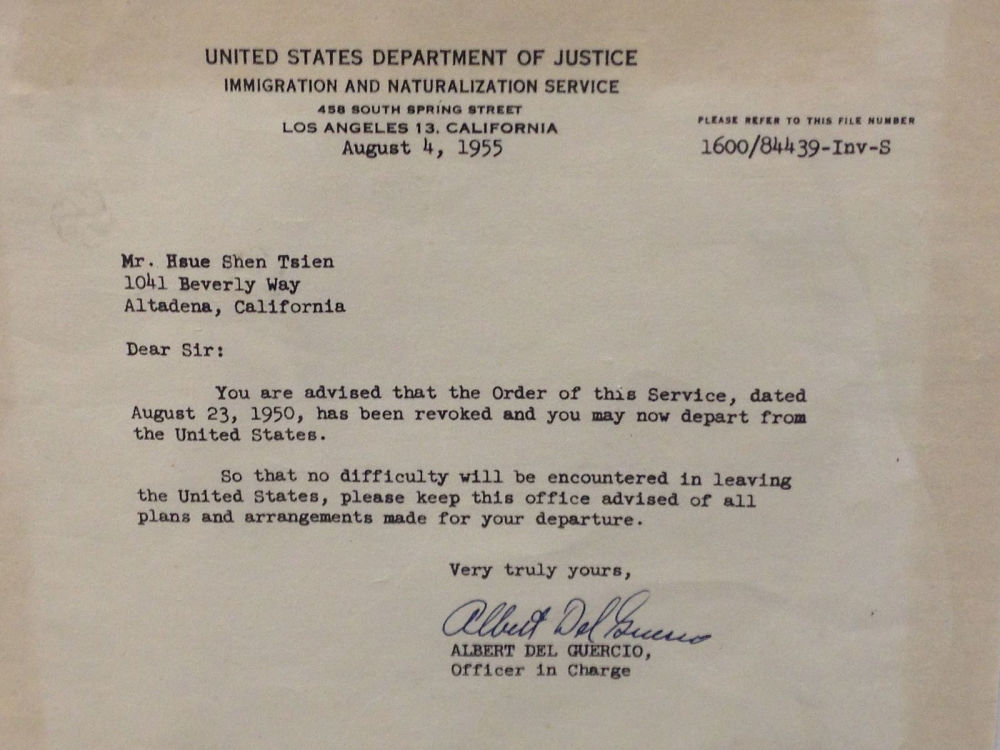

After losing his security clearance, Qian began to pack up, saying he wanted to visit his aging parents back home. Federal agents seized his luggage, which they claimed contained classified materials, and arrested him on suspicion of subversive activity. Although Qian denied any Communist leanings and rejected the accusation, he was detained by the government in California and spent the next five years under house arrest.

Five years later, in 1955, two years after the end of the Korean War, Qian was sent home to China as part of an apparent exchange for 11 American airmen who had been captured during the war. He told waiting reporters he “would never step foot in America again,” and he kept his promise (BBC 2020).

A letter from the US Immigration and Naturalization Service to Qian Xuesen, dated August 4, 1955, in which he was notified he was allowed to leave the US. The original copy is owned by Qian Xuesen Library of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where the photo was taken. (Caption and image via wiki).

Dan Kimball, who was the Secretary of the US Navy at the time, expressed his regret about Qian’s departure, reportedly stating, “I’d rather shoot him dead than let him leave America. Wherever he goes, he equals five divisions.” He also stated: “It was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a communist than I was, and we forced him to go” (Perrett & Bradley, 2008).

Kimball may have foreseen the unfolding events accurately. After his return to China, Qian did indeed assume a pivotal role in enhancing China’s military capabilities, possibly surpassing the potency of five divisions. The missile programme that Qian helped develop in China resulted in weapons which were then fired back on America, including during the 1991 Gulf War (BBC 2020).

Returning: Becoming a National Hero

The China that Qian Xuesen had left behind was an entirely different China than the one he returned to. China, although having relatively few experts in the field, was embracing new possibilities and technologies related to rocketry and space exploration.

Within less than a month of his arrival, Qian was welcomed by the then Vice Prime Minister Chen Yi, and just four months later, he had the honor of meeting Chairman Mao himself.

Qian and Mao (image source).

In China, Qian began a remarkably successful career in rocket science, with great support from the state. He not only assumed leadership but also earned the distinguished title of the “father” of the Chinese missile program, instrumental in equipping China with Dongfeng ballistic missiles, Silkworm anti-ship missiles, and Long March space rockets.

Additionally, his efforts laid the foundation for China’s contemporary surveillance system.

By now, Qian has become somewhat of a folk hero. His tale of returning to China despite being thwarted by the U.S. government has become like a legendary narrative in China: driven by unwavering patriotism, he willingly abandoned his overseas success, surmounted formidable challenges, and dedicated himself to his motherland.

Throughout his lifetime, Qian received numerous state medals in recognition of his work, establishing him as a nationally celebrated intellectual. From 1989 to 2001, the state-launched public movement “Learn from Qian Xuesen” was promoted throughout the country, and by 2001, when Qian turned 90, the national praise for him was on a similar level as that for Deng Xiaoping in the decade prior (Wang 2011).

Qian Xuesen remains a celebrated figure. On September 3rd of this year, a new “Qian Xuesen School” was established in Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, becoming the sixth high school bearing the scientist’s name since the founding of the first one only a year ago.

In 2017, the play “Qian Xuesen” was performed at Qian’s alma mater, Shanghai Jiaotong University. (Image source.)

Qian Xuesen’s legacy extends well beyond educational institutions. His name frequently appears in the media, including online articles, books, and other publications. There is the Qian Xuesen Library and a museum in Shanghai, containing over 70,000 artefacts related to him. Qian’s life story has also been the inspiration for a theater production and a 2012 movie titled Hsue-Shen Tsien (钱学森).2

Unanswered Questions

As is often the case when people are turned into heroes, some part of the stories are left behind while others are highlighted. This holds true for both Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen.

The Communist Party of China hailed Qian as a folk hero, aligning with their vision of a strong, patriotic nation. Many Chinese narratives avoid the debate over whether Qian’s return was linked to problems and accusations in the U.S., rather than genuine loyalty to his homeland.

In contrast, some international media have depicted Qian as a “political opportunist” who returned to China due to disillusionment with the U.S., also highlighting his criticism of “revisionist” colleagues during the Cultural Revolution and his denunciation of the 1989 student demonstrations.

Unlike the image of a resolute loyalist favored by the Chinese public, Qian’s political ideology was, in fact, not consistently aligned, and there were instances where he may have prioritized opportunity over loyalty at different stages of his life.

Qian also did not necessarily aspire to be a “flawless hero.” Upon returning to China, he declined all offers to have his biography written for him and refrained from sharing personal information with the media. Consequently, very little is known about his personal life, leaving many questions about the motivations driving him, and his true political inclinations.

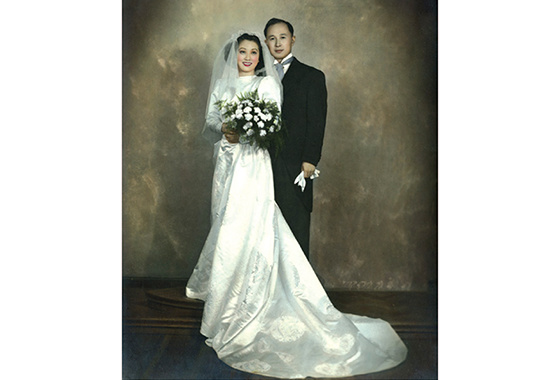

The marriage photo of Qian and Jiang. (Image source).

We do know that Qian’s wife, Jiang Ying (蒋英), had a remarkable background. She was of Chinese-Japanese mixed race and was the daughter of a prominent military strategist associated with Chiang Kai-shek. Jiang Ying was also an accomplished opera singer and later became a professor of music and opera at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing.

Just as with Qian, there remain numerous unanswered questions surrounding Oppenheimer, including the extent of his communist sympathies and whether these sympathies indirectly assisted the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Perhaps both scientists never imagined they would face these questions when they first decided to study physics. After all, they were scientists, not the heroes that some narratives portray them to be.

Also read:

■ Farewell to a Self-Taught Master: Remembering China’s Colorful, Bold, and Iconic Artist Huang Yongyu

■ “His Name Was Mao Anying”: Renewed Remembrance of Mao Zedong’s Son on Chinese Social Media

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

1 Some sources claim that Qian was born in Hangzhou, while others say he was born in Shanghai with ancestral roots in Hangzhou.

2The Chinese character 钱 is typically romanized as “Qian” in Pinyin. However, “Tsien” is a romanization in Wu Chinese, which corresponds to the dialect spoken in the region where Qian Xuesen and his family have ancestral roots.

This article has been edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

References (other sources hyperlinked in text)

BBC. 2020. “Qian Xuesen: The man the US deported – who then helped China into space.” BBC.com, 27 October https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-54695598 [9.16.23].

Monk, Ray. 2013. Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center, First American Edition. New York: Doubleday.

Perrett, Bradley, and James R. Asker. 2008. “Person of the Year: Qian Xuesen.” Aviation Week and Space Technology 168 (1): 57-61.

Wang, Ning. 2011. “The Making of an Intellectual Hero: Chinese Narratives of Qian Xuesen.” The China Quarterly, 206, 352-371. doi:10.1017/S0305741011000300

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

charles baer

September 6, 2022 at 12:42 am

you could say that this was the begining of W W I I .