Chapter Dive

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

From Comrade Trump to the Tariff Beauty, Trump has many nicknames on Chinese social media.

Published

9 months agoon

As the tariff turmoil between the US and China continues, President Trump has earned himself a new nickname on Chinese social media.

Over the years, Chinese netizens have come up with many different nicknames for the American President, whose Chinese name is usually transliterated as 川普 Chuānpǔ for phonetic reasons (read more here: Why Trump Has Two Different Names in Chinese).

But Chinese netizens call Trump many other things than just Chuānpǔ. You might have come across nicknames like “Comrade Build the Country” or “Build-the-Country Trump.”

Trump as China’s “Comrade Build-the-Nation”

“Build-the-Country Trump” or “Trump the Nation-Builder” (川建国 Chuān Jiànguó) has been an online joke on Chinese social media for years, often used alongside the related nickname “Comrade Build-the-Nation” (建国同志 Jiànguó Tóngzhì).

The joke began circulating in the early days of Trump’s first presidency, though even earlier there were humorous memes and satirical stories claiming Trump wasn’t truly American at all — the story goes that he was born in Zigong, Sichuan Province (四川自贡) in China.

When it was confirmed that Trump had won the presidency, proud Sichuan locals joked that he was one of their own, claiming that his Chinese name Chuānpǔ paid homage to their province, as it contained the “Chuan” from “Sichuan” (which literally means “river”). From this, an entire fabricated yet fascinating story about Trump’s Chinese roots emerged.

According to these stories circulating since late 2016, Trump’s father Fred Trump (referred to as Old Trump 老川普) was a businessman who came to China during World War II and stayed until 1947, supposedly a year after Donald’s birth. This version of events claims that Old Trump lived through both the Anti-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War while in China.

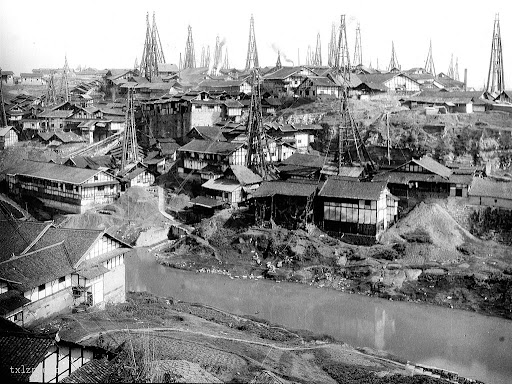

Zigong in 1929, the fabricated hometown of Donald Trump (image via Tianxia Laozhaopianwang).

The story further claims that the Trump family lived on Guangda Street in Zigong’s Guojia’ao neighborhood (光大街郭家坳), now the site of the Salt Industry Drilling Team’s club. Trump was said to have been born there before leaving China. Zigong is known for its high-quality, expensive salt, and according to the tale, ‘Old Trump’ shipped this salt to northern China or back to the US, earning a fortune that laid the foundation for the Trump family’s future wealth — and Trump’s eventual rise to the White House.

Old screenshot from a Weibo user who found it funny to discover the father-in-law actually believed the fabricated story about Trump being from Sichuan.

What does this entire online fairy tale have to do with Trump’s nicknames?

When Trump was in power, it soon appeared that he was doing all kinds of things that raised eyebrows. He once said that Korea used to be part of China, and then made a series of moves — like withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, pulling out of the Paris Climate Accords, and announcing that the US would leave UNESCO — which Chinese netizens saw as a weakening of US global influence, and therefore indirectly as a boost to China’s rising power. The trade war and Trump’s tough stance on Chinese tech companies were also, in a way, seen as forcing China into tech self-reliance, further accelerating the country’s domestic innovation.

Comrade Trump memes.

All of this combined earned Trump the nickname “Comrade Build-the-Nation,” jokingly fuelling the idea that he was actually China’s ‘secret agent’ on a mission to undermine American imperialism and support China’s rise on the world stage.

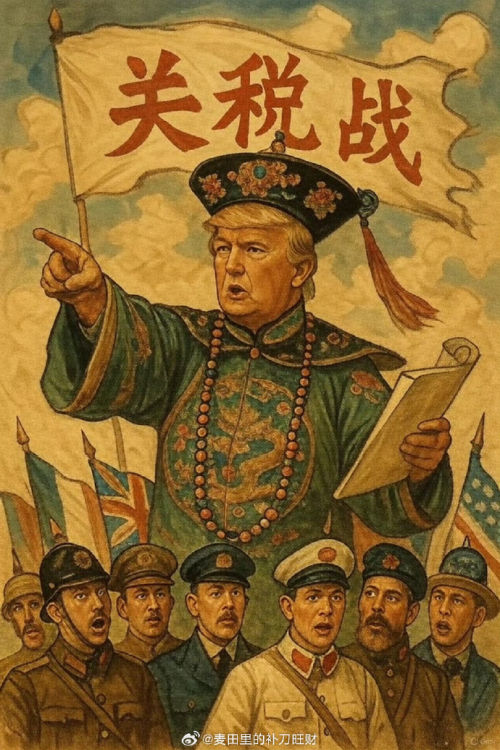

Trump the “Tariff Beauty”

Trump’s latest nickname incorporates some of the same sentiments that led to him being jokingly called a “comrade” of China.

Amid ongoing tariff tensions, some Chinese netizens,including some creators of meme-style ‘nation personification’ videos (鬼畜动画) on Douyin and Bilibili, as well as some commenters on Weibo and Xiaohongshu, have started referring to Trump as “税美人” (shuìměirén), which literally means “Tariff Beauty.”

Meme-style videos on Bilibili and Douyin titled “Shuimeiren.”

The nickname is a clever pun, since it sounds exactly the same as the Chinese name for the Sleeping Beauty fairytale: 睡美人 (shuìměirén) (there is also a South Korean 2016 movie of the same name 税美人, Tax Beauty).

What makes the nickname extra catchy is the wordplay: “税” (shuì) means “tax” or “tariff,” and “美” is also an abbreviation for America (from Měiguó, 美国). So, “税美人” not only brings to mind a fairytale princess, but also evokes the idea of “the American who taxes,” perfectly capturing Trump’s dramatic tariff policies in a playful way.

The nickname was especially used in comment sections when Trump began threatening additional tariffs, eventually bringing the total tariffs on Chinese goods to 145% on April 10.

Meanwhile, the “Comrade Trump” meme is more relevant than ever. Both China’s official and unofficial reactions to Trump’s tariffs reflect a general belief that the policies will ultimately harm the American economy and its global influence, while boosting China’s domestic market (also read our latest here).

Trump the Tariff Beauty, on Weibo.

On April 16, Harvard University Assistant Professor Moira Weigel published a commentary titled “Long Live Comrade Trump’s Tariffs” in The New York Times, which was later elaborately discussed by Chinese media outlet Guancha.

The article opens by briefly referencing China’s “Comrade Build-the-Nation” meme. Weigel argues that there’s some truth to the sentiment behind the nickname, suggesting that Trump’s tariffs won’t bring manufacturing back to the US, but will instead strengthen China’s position in global e-commerce. She notes that Americans will simply end up paying more for the same goods they’ve always bought, while Chinese companies are accelerating innovation, expanding internationally, and finding clever ways to circumvent tariffs by working with third-party companies and establishing US-based warehousing.

There’s perhaps also another layer to Trump’s new nickname — it also suggests that he is asleep, and, meanwhile, like the “Comrade” meme, is actually hurting the US and strengthening China. One netizen suggested that when it momentarily seemed Trump was backing down by exempting electronic goods from the tariff, a handsome prince had given him a kiss that made him wake up.

But with Trump later declaring that there was no “exception” at all, it seems that the confusion — as well as tariff tensions — are only growing. For now, there’s no happy ending in sight.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

PART OF WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: “THE US-CHINA TARIFF WAR ON CHINESE SOCIAL MEDIA“

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China World

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

How Chinese social media is making sense of the first geopolitical shockwaves of 2026.

Published

23 hours agoon

January 8, 2026

2026 hasn’t exactly seen a peaceful start. In a shocking turn of geopolitical events, Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro was captured by the US on Saturday. Facing narco-terrorism charges, he was flown to New York, where he is still being held in custody alongside his wife, Cilia Flores. President Trump announced that the United States would be taking control in Venezuela, stating they are going to “get the oil flowing.”

Maduro has pleaded not guilty to the charges during an initial hearing in federal court. Meanwhile, Maduro ally Delcy Rodríguez was formally sworn in as Venezuela’s interim president, while up to 50 million barrels of oil resources are set to go to the US.

Further shaking up geopolitical tensions were Donald Trump’s comments suggesting an American takeover of Greenland, arguing that the US needs to control Greenland to ensure the security of the NATO territory in the face of rising threats from China and Russia in the Arctic.

On Chinese social media, these developments have been dominating trending lists, with “Greenland” (格陵兰岛), “military force” (武力), “Trump” (特朗普), “Venezuela” (委内瑞拉), and “Maduro” (马杜罗) among the hottest keywords across various platforms from January 6 to today.

So what is the main gist of these discussions? From official reactions to dominant interpretive frames used by Chinese commentators and bloggers, there are various angles that are highlighted the most. I’ll explore them here.

🔴 China’s Official Response: Stressing Sovereignty & Strategic Ties

Chinese officials strongly condemned the capture of the Venezuelan president. Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) stated in Beijing on Sunday that China has never accepted the idea that any country has the right to act as an “international police” or an “international judge.” The Ministry of Foreign Affairs called for Maduro’s immediate release.

Spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) described the strikes on Venezuela as “a grave violation of international law and the basic norms governing international relations,” while spokesperson Mao Ning (毛宁) condemned what she called the United States’ “long-standing and illegal sanctions” on Venezuela’s oil sector.

These statements match the broader trajectory of China–Venezuela relations.

Over the past decades, particularly since Xi Jinping’s leadership began, the relationship between the two countries has evolved from a basic economic partnership into a more strategically significant one.

During Maduro’s 2023 visit to Beijing, the two sides elevated China–Venezuela ties to a so-called “all-weather strategic partnership” (全天候战略伙伴关系), signaling close, deep, and broad bilateral relations that go beyond a general partnership, with oil cooperation as a central pillar. (In 2025 alone, Venezuela exported around 470,000 barrels per day of crude oil to China.)

Following China’s condemnation of the US actions, Venezuelan Foreign Minister Gil expressed gratitude for China’s support, underscoring their bilateral friendship.

Beyond the official response to the recent developments, there are three main frameworks within which the ‘Trump turmoil’ is discussed on Chinese social media.

🔴 Three Main Angles in China’s Online Debate

🔷 1. Major Power Politics & US Aggression

Chinese media commentators are calling Trump’s capture of Maduro a potential “major turning point” for the world. While many described the developments as a sign that “the world has gone crazy” (这个世界太疯狂了), those trying to make sense of what happened see the US move as a warning: that relatively weak countries may increasingly become playgrounds for major powers & potential targets of US aggression.

Within this reading, China is portrayed as the most stable and peaceful superpower, increasingly important in a future multipolar world order.

On the popular podcast Qiánliáng Hútòng FM (钱粮胡同), recent developments were discussed as part of America’s dominant behavior on the world stage over decades. The hosts argued that, unlike previous US leaders, Trump is far less secretive about his goals and, in this case, no longer even follows the process of seeking UN authorization or congressional approval.

Similar views appeared elsewhere, including in a trending Bilibili video by the political commentary channel Looking at America from the Inside (内部看美国), which described the Venezuela raid not as an endpoint, but as a “signal” of what is yet to come, as the US, sensing structural decline, increasingly acts reactively rather than strategically.

Zhihu author Fēng Lěng Mù Shī (枫冷慕诗), whose post rose in the platform’s popularity charts on Wednesday, also framed the moment as pivotal. While the US may once have held the upper hand, they argue, other countries now have an actual choice in which side to take in a world ruled by superpowers. They write:

💬 “If the US truly had the strength to crush everyone and dominate everything completely, it might still be able to control global affairs. But now, with the rise of China, countries bullied by the US have new choices. If you were one of them, what would you choose? To cooperate with a bandit who might kill you with an axe at any moment? Or to cooperate with a reasonable businessman who follows the rules? I believe any rational person would make the obvious choice.“1

Social media posts made with AI featuring “Know-It-All Trump” or “The King of Understanding.”

At the same time, US behavior also became a source of banter. Some netizens, from Bilibili to Xiaohongshu, posted about “The Know-It-All King” (懂王 Dǒng Wáng—a Chinese nickname for Trump reflecting his often-quoted claims to understand complex issues better than anyone) as a comical villain on a shopping spree for new territories to conquer.

Weibo post: a creative solution to the Greenland issue?

One poster offered a creative solution to the Greenland issue:

💬 “Regarding Greenland, a simple diplomatic solution would be for Barron Trump [Trump’s son, b. 2006] to marry Princess Isabella [of Denmark, b. 2007], with Greenland given to the United States as the dowry. 😁”

🔷 2. The Taiwan Parallel

Taiwan also quickly entered the discussion. In English-language media, some commentators suggested that the raid on Venezuela could smooth and accelerate Beijing’s path toward taking Taiwan.

China’s Taiwan Affairs Office firmly rejected such comparisons. Spokesperson Chen Binhua (陈斌华) emphasized that the Taiwan issue is China’s internal affair and fundamentally different from Venezuela’s situation. Many social media commenters also argued that comparing Venezuela to Taiwan makes little sense, stressing that Venezuela is a sovereign state while Taiwan is considered a province of China.

Even so, Taiwan continues to surface in discussions on Venezuela in various ways. Some users jokingly suggested that the US has now provided a “copy-paste example” of what a tactically impressive raid might look like, while others more seriously draw comparisons between the arrest of Maduro and a hypothetical arrest of Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te.

The central question in these debates, also raised by Taiwanese media commentator Hou Han-ting (侯汉廷), is this: if Lai Ching-te were captured alive in Beijing today, what right would the United States have to object? A common view in these discussions is that Trump’s actions lower the threshold for such scenarios and implicitly pave the way for China’s ‘reunification’ with Taiwan.

This reading seems to sharply contrast Washington’s own framing. In a speech on Monday, US Defense Secretary Hegseth described China as the US’s primary competitor and claimed that America is “reestablishing deterrence that’s so absolute and so unquestioned that our enemies will not dare to test us.”

On Chinese social media, however, this claim is openly questioned: does the raid on Venezuela actually deter China or Russia, or does it instead give them greater freedom of action?

💬 As political commentator Hu Xijin wrote on Weibo: “Americans might do well to ask the Taiwan authorities, and look at the global media commentaries, if the US military action in Venezuela has made the Democratic Progressive Party authorities pushing Taiwan independence feel more secure, or more anxious?”2

🔷 3. Little Europe and the Big Striped Wolf

A third major angle centers on Europe’s role. Hu Xijin has been particularly active in commenting on these developments, especially after Tuesday’s joint statement by the leaders of seven European countries pushing back against Trump’s Greenland remarks.

Hu described the moment as one of “unprecedented turmoil within the Western bloc” and, with Denmark (including Greenland) being a NATO member, as a signal of “the collapse of the so-called ‘values alliance’.”3 This idea was further strengthened by Trump’s withdrawal from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, alongside exits from 65 other organizations, which he described as “contrary to the interests of the United States.”

On Chinese social media, Europe is, on the one hand, seen as one of the weakest actors in this geopolitical episode, while at the same time being criticized as the biggest “hypocrite.”

This week’s joint statement—and Europe’s broader position—are framed as weak due to Europe’s structural dependence on the US.

Weibo commentator Zhang Jun (@买家张俊) argues that Europe leans on a “rules-based international order” which, in reality, would amount to little more than a “US-based order” should Trump succeed in taking Greenland. At the same time, the European statement lacked economic sanctions or concrete follow-up measures, amounting to little more than mere rhetoric.

💬 As one nationalistic account put it: “Europe wonders why, even after kneeling down and licking America’s shoes, it still ends up getting hit.”4

Europe is mainly criticized for being “hypocritical” for remaining largely silent on Venezuela, while forcefully defending Greenland’s sovereignty once Trump turned his attention there.

Britain, in particular, has been singled out in Chinese media narratives surrounding the developments in Venezuela. Guancha ran a piece accusing the BBC of instructing journalists not to use the word “kidnap” when describing Maduro’s capture, suggesting the broadcaster was “whitewashing” the US’s illegal actions. It also pointed to Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s response in a BBC interview, describing his comments on US actions against Venezuela as “playing tai chi” (打起了太极)—a Chinese idiom for being evasive and dodging the question.

One Weibo user (@突破那一天) noted that a Jan 5 speech by Foreign Secretary Cooper appeared to frame US actions as contextually justified, while simultaneously stressing that Greenland’s future is a matter solely for Greenlanders and Danes—accusing her of applying a double standard on sovereignty and speaking out clearly only when the target is a Western ally.

Other users summed up Europe’s role as one of “deceiving others and deceiving themselves” (自欺欺人).

Another commenter suggested that Europe has been so focused on perceived threats from Russia and China while throwing itself into America’s arms, that it failed to notice the real danger. “Oh Europe, little piggy Europe,” they mocked. “You’ve let the wolf into the house.”

🔴 “You Think the US Invasion of Venezuela is None of Your Concern?”

How unexpected was the American military operation in Venezuela, really? One final aspect that trended online was how eerily familiar it all felt.

In the second book of the popular 2008 Chinese sci-fi trilogy The Three-Body Problem, author Liu Cixin (刘慈欣) described a scenario in which Venezuela, ruled by the fictional President Manuel Rey Diaz, is attacked by the US. That Venezuela storyline from the sci-fi novel has become widely discussed for its parallels to the current developments.

The Three Body Problem from 2008 featured a storyline about the US invading Venezuela.

The famous Japanese anime series Black Jack (怪医黑杰克) by Osamu Tezuka (1928–89) also went trending for featuring a fictional plot that many netizens see as strikingly similar to what happened in Venezuela.

It involves the president of the United Federation, named Kelly, citing “global justice” to justify cross-border airstrikes on the presidential residence of the small, oil-rich fictional country Republic of Aldiga, before arresting its leader, General Cruz. Some netizens noted how the blond President “Kelly” even somewhat resembles Trump.

Scenes from Black Jack (怪医黑杰克) by Osamu Tezuka

(Some commenters argued that Osamu Tezuka was not predicting the future so much as drawing on an already familiar pattern of US interventions abroad, and that the character “Kelly” was more likely modeled on Ronald Reagan.)

In Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem, there’s a classic line told by retired Beijing teacher Yang Jinwen to former construction worker Zhang Yuanchao, who dismisses world news as “irrelevant”. In the book, Yang tells him:

📖 “Every major national and international issue, every major national policy, and every UN resolution is connected to your life, through both direct and indirect channels. You think the US invasion of Venezuela is none of your concern? I say it has more than a penny’s worth of lasting implications for your pension.”5

In the current situation, some netizens think that the quote needs to be rewritten. In 2026, it would be:

💬“Do you really think the US arresting Venezuela’s president Maduro, conflicts in the Middle East, tensions across the Taiwan Strait, or Europe’s energy crisis are none of your concern? Don’t be naive. They drive up electricity bills, food prices, and mortgage rates. In the end, what gets drained is both your wallet and your future retirement security.”

It’s clear that many people are, in fact, deeply concerned about these geopolitical developments. As some have noted, science fiction is not always about distant futures. Sometimes, it turns out, we are already living in them.

In Liu Cixin’s version of the story, ‘Rey Diaz’ drives the Americans away through a united fight of the people, breaking the streak of victories by major powers over developing countries and turning the Venezuelan president into a hero of his time.

This story, I suspect, is going to end very differently. For now, it is still being written.🔚

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 “如果说美国人有实力碾压一切,彻底的一家独大,那或许他还可以继续操控世界的局势,但如今随着咱们的崛起,全世界被美国欺凌的国家就有了新的选择,假如你是他们,你会做出什么样的决定? 是和一个随时会砍死你的强盗合作?还是和一个讲道理讲规则的生意人合作?我觉得所有的正常人都会做出合理的判断.”

2 “美国人最好问一问台湾当局,也看一看世界媒体的评论:美军在委内瑞拉的行动究竟让推动“台独”的民进党当局更加安心了,还是更加惶恐不安了?”

3 “欧洲7国领导人和丹麦领导人共同发表声明,反对美国吞并格陵兰岛,这标志着西方集团前所未有的内乱以及 它们的所谓”价值同盟”面临崩溃.”

4 “欧洲:我都跪下舔美国鞋子了、你为什么还要打我.”

5 “我告诉你老张,所有的国家和世界大事,国家的每一项重大决策,联合国的每一项决议,都会通过各种直接或间接的渠道和你的生活发生关系。你以为美国入侵委内瑞拉与你没关系?我告诉你,这事儿对你退休金的长远影响可不止半分钱”

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Eye on Digital China/What’s on Weibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Chapter Dive

Why Were 100,000 Pregnant Women’s Blood Samples Smuggled Out of China?

How and why fetal sex testing became a national security story

Published

2 weeks agoon

December 25, 2025

A noteworthy story in Chinese media recently, which also made it to the top trending lists on Kuaishou and Weibo, concerns the uncovering of a widespread criminal network that smuggled blood samples from over 100,000 pregnant women across the border, exposing a black-market chain active across all provinces of China. In this deeper dive, I look at what received far less attention: why so many pregnant women were willing to provide their blood in the first place.

The case was part of a major operation by Guangzhou’s anti-smuggling authorities following a year-long investigation and the mobilization of 265 officers. As part of the operation, two professional criminal groups specializing in the smuggling of pregnant women’s blood samples were dismantled, and a total of 26 people were arrested.

The groups earned a staggering 30 million yuan (US$4.2 million) from their blood-smuggling activities.

So far, the story reads almost like a vampire novel, especially with Chinese media detailing how the blood was smuggled: smugglers reportedly strapped tubes of blood to their bodies to cross the border. Others hid them in specially modified suitcases with concealed compartments.

Some commenters framed the story as the smuggling of “life samples carrying the genetic code of Chinese citizens,” and as the “poaching of ethnic genetic resources,” arguing that the data security implications could be serious if the blood were to be used for research by those with ulterior motives.

Other netizens suggested that “insiders within medical institutions must be involved,” possibly even through broader “cross-border project collaborations.” These suspicions were fueled by official reporting. Overall, the online media discourse surrounding the case focused on the risks these practices pose to national biosecurity, with fears that foreign entities could appropriate China’s human genetic information.

In reality, however, this story is about the widespread demand in China for prenatal blood testing for fetal sex determination.

The groups uncovered by Guangzhou authorities received blood from some 100,000 pregnant women because the women provided it themselves. The groups (illegally) advertised on social media that they offered non-invasive fetal sex identification and genetic disease screening, with clients paying fees of 2,000–3,000 yuan (US$285–US$426) for these blood tests.

According to Guancha.cn, the blood would be drawn by “acquaintances” or through online medical platforms, after which the samples would be mailed by courier to a designated address, where they were collected, concealed by smugglers, and delivered to overseas laboratories for testing.

Smuggled blood as seen in CCTV feature

Although none of the Chinese news reports on this case disclose where these “overseas labs” are actually located, the reports mention cooperation between authorities in Guangzhou, Foshan, and Shenzhen, and the details provided make it highly probable that the case concerns the mainland–Hong Kong border.

In a recent CCTV feature on the news, Zheng Zhong (郑重), Deputy Director of the Investigation Division of the Guangzhou Customs Anti-Smuggling Bureau, said:

“China has explicitly prohibited the determination of fetal sex for non-medical needs, which is a protection of the fetus’s right to life. It is also to maintain a healthy population ratio. Blood sample smuggling poses a high potential risk to public interests and national biosecurity.”

Fetal sex determination has been illegal in China since the first regulation in 1989, with later laws specifically outlawing the use of ultrasound imaging or other techniques to identify fetal sex.

Why Fetal Sex Determination Still Matters

Why did Zheng mention the prohibition of fetal sex determination tests in China to “maintain a healthy population ratio”?

Although abortion has generally been permitted in China—which has one of the most lenient abortion regimes in the world—strict controls on sex-selective abortions have been in place since the early 1990s.

One of the unintended effects of China’s one-child policy since 1979 has been the widespread occurrence of sex-selective pregnancy terminations, linked to traditional son preference. Fetal sex identification has been a precursor to these abortions, contributing to severe distortions in the country’s sex ratio. Non-medical fetal sex identification and sex-selective abortion came to be known as the “two illegitimates.”[1]

Now that China is entering its first decade since the end of the one-child policy, you might expect that these “two illegitimates” have become less pressing issues. After all, with couples now allowed to have more than one child (even three children or more), why would sex determination still be so relevant that 100,000 women would continue to submit blood samples despite the practice officially being illegal?

🔎 In reality, research suggests that the end of China’s one-child policy has not been the turning point it was perhaps expected to be. Although it has reduced pressures, its impact on son preference and sex-selective practices has been somewhat underwhelming.[2]

Since 2016, there has indeed been a rise in daughter preference and gender indifference, as well as a decline in male-to-female sex ratios at birth, but significant regional differences remain and son preference persists, alongside sex-selective abortion.[3] As a result, the sex ratio at birth remains skewed in certain provinces, especially for first births.[4]

👉 So what does this mean in practice? It means that, despite laws and regulations, expecting parents are still eager to find ways to identify fetal sex by whatever means possible (blood-based tests, ultrasound scans), and that agencies able to profit from this desire have been widespread for years.

In provinces like Jiangxi, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hubei, and Hunan, which together with Hainan accounted for more than a third of all births in China in 2020, there is still a deeply rooted familism culture and an abnormally high number of male births.[5]

Even though Chinese authorities introduced specific measures more than a decade ago to ban the mailing of blood samples overseas for fetal sex identification, underground networks smuggling fetal blood samples to Hong Kong for gender testing have been rampant—and this goes well beyond 100,000 samples.

Framing Pregnant Women’s Blood Smuggling in Chinese State Media

It is noteworthy that Chinese coverage of this case leaves out issues related to fetal sex selection, the persistence of sex-selective practices in post–one-child China, and parents’ willingness to learn the sex of their fetus to such an extent that they are prepared to pay large sums of money for this information.

In the 8-minute CCTV feature on this case, as well as in other reports, the core narrative centers on how an organized criminal network that endangered national biological security by illegally smuggling pregnant women’s blood samples was successfully dismantled by Chinese authorities through state surveillance and coordinated law enforcement.

China has, in fact, strict laws on the protection of human genetic resources. Since 2019, regulations have specifically prohibited foreign entities from collecting genetic material within China and restricted the transfer of genetic material and related data out of China. Any research involving Chinese human genetic resources must be conducted through approved collaboration with a qualified Chinese institution (see China Law Translate).

In the CCTV report, fetal sex identification is mentioned only briefly: first, in describing how the criminal group attracted customers online, and second, by Zhong, to emphasize that the practice is illegal. This framing places the entire issue within the domains of legality, regulation, and security, while the ethical, socio-cultural, and gender dimensions that lie at the root of the practice are entirely ignored.

Word cloud generated with the assistance of AI, based on the fully transcribed and translated text of the main CCTV investigative report on the blood-smuggling case.

Instead, the case is narrated using dominant language such as “blood smuggling,” “genetic resources,” and “security.” This framing has led to some confusion online. One of the most popular search queries related to the story on Weibo was: “What is the purpose of smuggling pregnant women’s blood samples abroad?” (孕妇血液样本走私境外目的是什么).

On Xiaohongshu, some commenters similarly asked: “I just don’t understand what pregnant women’s blood is used for.” Another user replied: “They can extract genetic codes, create a virus, and kill us with it.”

There are, however, many commenters who directly connect the case to its underlying issue. One woman on Xiaohongshu asked: “Isn’t it possible to tell [the fetus’s sex] just by doing a B-ultrasound? Why would they spend so much money to draw blood?” Another commenter replied: “It takes several months before you can do an ultrasound. A blood test is faster, and you can know the result before the abortion deadline.” (In some regions of China, non-medical abortions are not permitted after 14 weeks of pregnancy.)

Demographic Anxiety and Shifts in Narratives

Chinese headlines about the uncovering of the blood-smuggling operations appeared in the same week when netizens discussed unofficial reports about China’s 2025 estimated birth rates, suggesting that the country’s fertility rate will hit another historic low and fall to second-lowest in the world (higher only than South Korea), with a total fertility rate of about 1.09.

“Let people with money have kids,” some commenters suggested. “Right now, it’s hard for young people to get a job. When you can’t even find a job, who would think of having kids?”

Another person on Weibo wrote: “I’m part of the elite social class with a PhD degree, and yet I’m miserable. I’m pessimistic and disappointed about the future. I won’t have kids, won’t buy [a house], and won’t get married.”

Over the past years, and especially recently, Chinese authorities have introduced numerous measures in attempts to boost the country’s birth rates, from child-rearing subsidies to taxes on contraceptives.

In this light, tackling illegal practices involving fetal sex identification is more relevant than ever—and pushing such news to the top of China’s trending lists, together with frightening narratives about blood thieves and biosecurity risks, serves as a warning as much to smugglers as to expecting mothers not to engage in such practices. In this context, expecting parents would not only be crossing legal red lines by testing the sex of their unborn child, but would also be framed as handing over China’s national DNA to potential foreign enemies.

🔴 In doing so, Chinese official narratives shift, yet also fall back into old habits: at a time when fertility is dramatically dropping and confidence among young people in love & marriage is eroding, the state does more than regulate or guide ideas about family planning and fetal sex determination; it changes the meanings attached to it.

But there’s also a side effect to these stories. Because official news coverage presents the case as one of potential risks of Chinese genetic data being stolen, while largely leaving out the relevant social context, some ordinary Chinese netizens have begun to worry about what happens to their blood samples at hospitals once they leave their check-up appointments.

“Can they profit from it?” some wonder, while others worry about unintentionally contributing to future biological warfare.

Ultimately, the story of “blood smuggling” is not just about smugglers or overseas laboratories. It is about how, in an era of increasing demographic anxiety, reproductive behavior is increasingly reframed through the language of security.

Luckily, many genuinely don’t see what all the fuss is about: “People would really smuggle pregnant women’s blood abroad for what? Is it really so important to know whether you’re having a boy or a girl?”🔚

📌🎬 Although I also published last week, I didn’t send that article as a newsletter. So, in case you missed it, here’s a short recap: the past year has been a tumultuous one for China’s entertainment industry, and especially for renowned director Wong Kar-wai. After the success of the TV drama Shanghai Blossoms, a former screenwriter accused Wong and his team of discrediting, exploiting, and abusing him.

The case was already explosive, but it became even more sensitive when audio recordings were leaked in which Wong criticised the Party. Almost any other celebrity would likely have been blacklisted for such remarks, yet Wong seems to have escaped that fate. Why? You can explore the case in this in-depth article by Ruixin Zhang. It’s worth the read.

👉 This piece is part of Chapters, the format I use for deeper, more analytical pieces. Alongside Chapters, I also publish Signals, which tracks slower-moving shifts in Chinese online culture and digital life, and China Trend Watch, which offers a regular overview of what has been trending across China’s digital platforms. Keep an eye on the upcoming editions to follow the thread.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

[1] Ruby Lai Yuen Shan, “The Transformation of Abortion Law in China,” in Research Handbook on International Abortion Law, edited by Mary Ziegler (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023), 172–73.

[2] Xinyi Zhang, “Estimating the Effect on the Sex Ratio of the Two-Child Policy: Evidence from China,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies 9 (2023): 1–8.

[3] Li Mei and Quanbao Jiang, “Sex-Selective Abortions over the Past Four Decades in China,” Population Health Metrics 23, no. 6 (2025): 1–16.

[4] Mengjun Tang and Jiawei Hou, “Changes of Sex Ratio at Birth and Son Preferences in China: A Mixed Method Study,” China Population and Development Studies 8 (2024): 1–27.

[5] Tang and Hou, “Changes of Sex Ratio at Birth,” 4–5.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

Why Were 100,000 Pregnant Women’s Blood Samples Smuggled Out of China?

When an Entertainment Scandal Gets Political: How Wong Kar-wai Survived a Nationalist Storm

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment6 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment6 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital12 months ago

China Digital12 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest