China Through Others’ Lens

Published

1 month agoon

Dear Reader,

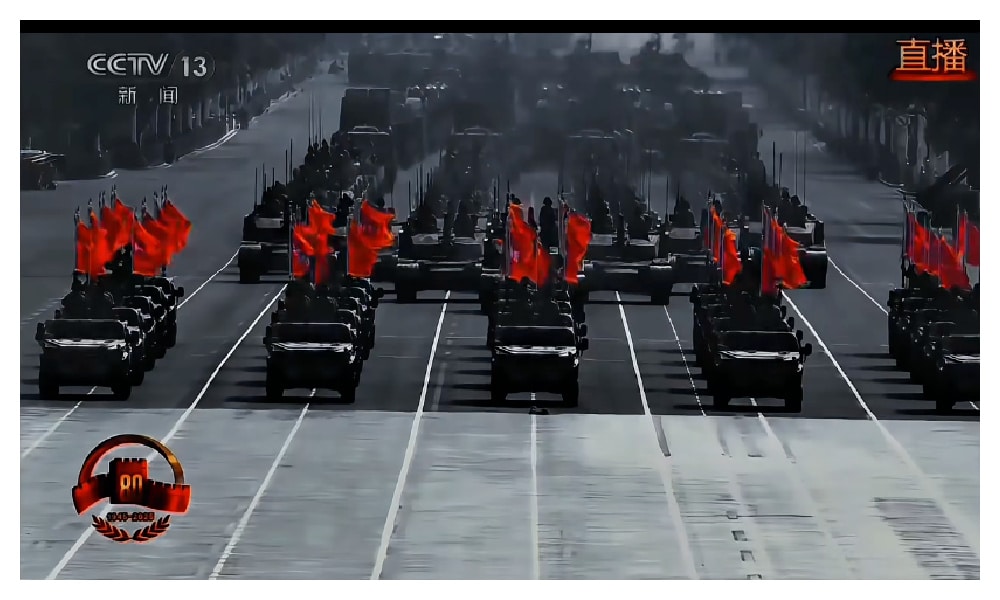

The past week following the military parade, Chinese social media remained filled with discussions about the much-anticipated September 3 V-Day parade, a spectacle that had been hyped for weeks and watched by millions across the country.

That morning, Chinese leader Xi Jinping, accompanied by his wife Peng Liyuan, welcomed international guests on the red carpet. When Xi arrived at Tiananmen Square alongside Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, office phone calls across the country quieted, and school classes paused to tune in to one of China’s largest-ever military parades along Chang’an Avenue in Beijing, held to commemorate China’s victory over Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

As tanks rolled and jets thundered overhead, and state media outlets such as People’s Daily and Xinhua livestreamed the entire event, many different details—from what happened on Tiananmen Square to who attended, and what happened before and after, both online and offline—captured the attention of netizens.

Amid all the discussions online (we will list more of them further in this newsletter), one particularly hot conversation was about the visual coverage of the event, and focused on AFP (法新社), Agence France Press, the global news agency headquartered in Paris.

Typing “AFP” (法新社) into Weibo in the days after the parade pulled up a long list of hashtags:

“Has AFP released their shots yet?” -“V-Day Parade through AFP’s lens” – “AFP’s god-tier photo” – “Did AFP show up for the parade?”

The fixation may seem odd—why would Chinese netizens care so much about a French news agency?

The story actually goes back to 2022. In July of that year, on the anniversary of the Communist Party’s founding, one Weibo influencer (@Jokielicious) noted that while domestic photographers portrayed the celebrations as bright and triumphant, she personally preferred the darker, almost menacing image of Beijing captured by Western journalists.

In her view, through their lens, China appeared more powerful—even a little terrifying.

The post went viral. Soon, netizens began comparing more of China’s state media photos with those from Western outlets. One photo in particular stood out: Xinhua’s casual, cheerful shot of Chinese soldiers contrasted sharply with AFP’s cold, almost cinematic frame.

Netizens joked that Xinhua had made the celebration look like the opening of a new hotel, while AFP had cast it as “the dawn of an empire.”

Gradually, what began as a dig at the bad aesthetics of state media turned into something else: a subtle shift in how Chinese netizens were rethinking their country’s international image.

Under the hashtag #ChinaThroughOthersLens (#老中他拍), netizens shared images of China as seen through the lenses of various Western media outlets.

This wasn’t the first time such talk had appeared. In the early days of the Chinese internet, people often spoke of the so-called “BBC filter.” The idea was that the BBC habitually put footage of China under a grayish filter, making its visuals give off a vibe of repression and doom, which many felt was at odds with the actual vibrancy on the ground. To them, it was proof that the West was bent on painting China as backward and gloomy.

These discussions have continued in recent years.

For example, on Weibo there were debates about a photo of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, shot by Peter Thomas for Reuters, and used in various Western media reports about Wuhan and Covid as early as 2021. The top image shows the photographer’s vantage point.

“Looks like a cockroach in the gutter,” one popular comment described it.

Another example is the alleged “smog filter” applied by Western media outlets to Beijing skies during the China visit of US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in 2024.

AFP, meanwhile, seemed to offer a different kind of ‘distortion.’

Netizens said AFP’s photos often had a low-saturation, high-contrast, solemn tone, with wide angles that made the scenes feel oppressive yet majestic. Over time, any photo with that look—whether taken by AFP or not—was dubbed the “AFP filter” (法新社滤镜).

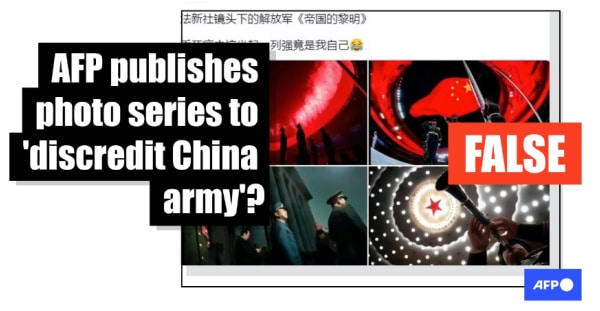

AFP has clarified multiple times that many of the viral examples weren’t even theirs—or that they were, but had been altered with an extra dark filter. They also refuted claims that AFP had published a photo series of Chinese soldiers titled “Dawn of Empire” to discredit China’s army.

Nevertheless, the “AFP filter” label stuck. It became shorthand for a Western gaze that cast China not as impoverished or broken—as some claimed the “BBC filter” did—but as formidable, like a looming supervillain.

One running joke summed it up neatly: domestic shots are the festive version; Western shots are the red-tyrant version. And increasingly, netizens admitted they preferred the latter, commenting that while AFP shots often emphasize red to suggest authoritarianism, they actually like the red and what it stands for.

So, when this year’s V-Day came around, many were eager to see how AFP and other Western outlets would frame China as the dark, dangerous empire.

But when the photos dropped, the reaction was muted. They looked average. Some called them “disappointing.” “Where are the dark angles? Not doing it this time?” one blogger wondered. “Where’s the AFP hotline? I’d like to file a complaint!”

“Xinhua actually beat you this time,” some commented on AFP’s official Weibo account. Others agreed, putting the AFP photos and Xinhua photos side by side.

To make up for the letdown, people began editing the photos themselves—darkening the tones, adding dramatic shadows, and proudly labeling them with the tag “AFP filter” or calling it “The September 3rd Military Parade Through a AFP Lens” (法新社滤镜下9.3阅兵).

“Now that’s the right vibe,” they said: “I fixed it for you!”

Official media quickly picked up on the trend. Xinhua rolled out its own hashtags—#XinhuaAlwaysDeliversEpicShots (#新华社必出神图的决心#) and #XinhuaWins (#新华社秒了#)—and positioned itself as the true master of a new aesthetic narrative.

The message was clear: China no longer needs the Western gaze to frame itself as powerful or intimidating; it can do that on its own.

The “AFP v Xinhua” contest, the online movement to “AFP-ify” visuals, and the Chinese fandom around AFP’s moodier shots may have been wrapped in jokes and memes, but they also pointed to something deeper: the once “demonized” image of China that Western media pushed as threatening is now not only accepted by Chinese netizens, it’s embraced. Many have made it part of a confident, playful form of online patriotism, applauding the idea of being seen by the West as fearsome, even villainous, believing it amplifies China’s global authority.

As one netizen wrote: “I like it when we look like we crawl straight into their nightmares.”

Chinese journalist Kai Lei (@凯雷) suggested that these kinds of trends showed how the Chinese public plays an increasingly proactive role in shaping China’s global image.

By now, the AFP meme has become so strong that it doesn’t even require AFP anymore. Ultra-dramatic shots are simply called “AFP-level photos” (法新社级别).

For now, as many are enjoying the “afterglow” of the military parade, their appreciation for the AFP-style only seems to grow. As one Weibo user summed it up: “AFP tried to create a sense of oppression with dark, low-angle shots, but instead only strengthened the Chinese military’s aura of majesty.”

– By Ruixin Zhang and Manya Koetse

PS from Manya: For the Dutch-speaking readers here: last week, I spoke on NPO Radio 1’s OVT about China’s military parade and how the country remembers and politicizes its wartime past from cinemas to social media. You can watch/listen the full interview here.

What’s Featured

A deeper dive behind the hashtag

An American Problem | The shocking Charlie Kirk shooting has become a huge topic of debate this week, and also went trending on Chinese social media, where Kirk was mostly described as “Trump’s ally” (特朗普盟友). How are Chinese netizens responding to his death? Although opinions and sentiments are mixed, most agree that his death is an ‘American problem.’ We covered the reactions:

What’s Trending

Popular Topics at a Glance

In the last newsletter, I promised to follow up with more ‘post-parade’ responses. On Weibo and other social media platforms in China, hundreds of hashtags have emerged around the theme of the “afterglow after the parade” (阅兵后劲). In addition to the featured ‘AFP versus Xinhua’ discussion, here are some other noteworthy social media trends following the September 3 event, which turned out to be one of China’s largest military parades:

1 🇨🇳 “I’m So Happy in China”: Putin and Kim Jong-un’s Daughter in the Picture

Besides everything happening on Tiananmen Square during the parade, many netizens were just as interested—if not more—in what was going on at the sidelines. The presence of Putin and Kim Jong-un drew a lot of attention, and since political discussions are highly controlled on Chinese social media—especially during such high-profile events—online conversations mostly focused on smaller, more personal details.

One viral clip posted by Ta Kung Wen Wei Media (大公文匯網, a pro-Beijing Hong Kong media outlet) showed Putin during his various visits to China, where he always seems to enjoy local delicacies. The video’s caption read: “You have no idea how happy I am in China!” (“我在中国的快乐谁懂啊?!”).

As for Kim Jong-un, his daughter Kim Ju Ae, who accompanied him on this trip to China, became the social media star of the day. Many netizens still remembered her from a few years ago, when she joined her father at a Pyongyang military banquet and a widely publicized military parade. At the time, she was believed to be around ten years old, and Chinese bloggers nicknamed the round-cheeked girl “Golden Chubby” (金胖子) and “Golden Fourth Fatty” (金四胖).

Now, however, the little girl has grown into a young lady. Many praised her style and grace, calling her a “little princess” (小公主). The hashtag “Kim Jong-un brought his daughter” (#金正恩把女儿金主爱带来了#) garnered over 190 million views on Weibo.

2 🎥 An Unexpected Face at Military Parade: US Pawnshop Owner Evan Kail

The American Evan Kail, a former pawnshop owner from Minnesota, was among the more unexpected faces at the parade. He appeared to be a semi-official guest, not watching the parade from Tiananmen Square but instead joining hundreds of locals to view it via livestream at the Temple of Heaven, where he was surrounded by cameras and media—making his attendance part of the broader media circus surrounding the military parade (#埃文凯尔天坛观看阅兵直播#).

Kail first went trending in 2022, when he posted a video asking for help after coming across an old war photo album he believed contained rare and previously unseen images of the Nanjing Massacre. He eventually donated the album to China. Although the book reportedly turned out not to contain photos of Nanjing but rather of Shanghai (with some images likely being mass-produced souvenir photos—and the authenticity of the album not really being the focus here), Kail is still well respected in China for bringing international attention to the atrocities of Nanjing. He recently published a book in China, and his story has been widely promoted by Chinese state media outlets.

3🏅 Parade Soldiers’ Sunburn Tan Lines Praised as “Special Medals”

Some of the post-parade “afterglow” discussions on social media focused on videos showing soldiers returning from the September 3 parade. They were easily recognizable at train stations and airports by the stark sun lines on their faces—caused by long hours of outdoor training and marching while wearing helmets with chin straps (see videos).

The “special medal” sun lines

Netizens called the marks a “special medal” (特殊的勋章), and the clips of soldiers returning home with their sunburnt faces also added a more vulnerable and human touch to those perfect military formations.

4 🤐 Man Detained Over “Parade-Insulting Comments”

It wasn’t all roses online during the military parade—although most netizens probably wouldn’t have noticed due to strict censorship. Some people were punished for expressing online criticism. One 47-year-old man surnamed Meng (孟) from Hubei was turned into a warning for others and was detained after posting “insulting” comments about the September 3 military parade on a livestream on WeChat. Another man from Tianjin saw his Weibo page blocked after he suggested that watching the parade is a shallow or fake form of patriotism—and it’s highly likely he was not the only one.

5 🚀 Military Model Toys Boom 175% in Sales Following Parade

Another post-parade effect: China has seen a surge in consumer interest in military-themed toys, from fighter jets to missiles and tanks. Starting on September 3, the military model category on Chinese e-commerce platform JD.com reported a 175% increase in sales.

6 🪖 The Next Military Parade

Thought this was it? Not quite. Chinese media are already stirring anticipation for future military parades with the hashtag “Looking Forward to the Next Military Parade” (#期待下次阅兵了#). While nothing has been confirmed, the next likely milestone years for large-scale parades are 2027 (the People’s Liberation Army’s 100th anniversary) and 2029 (the 80th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China). To be continued…

What’s Noteworthy

Small news with big impact

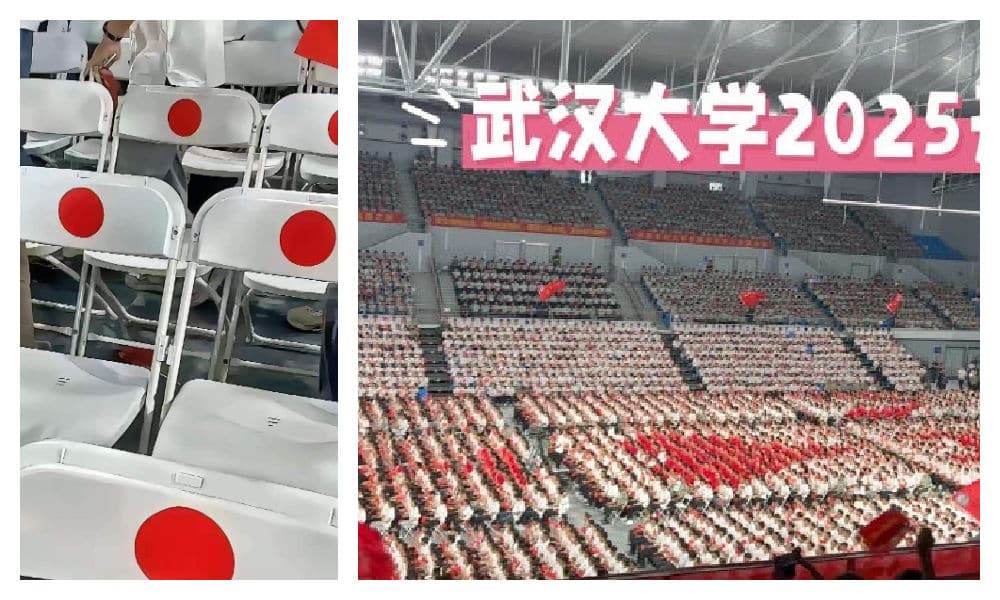

In these days after the big parade, when the history of war is a major theme in China, Wuhan University chose a particularly unfortunate and poorly timed way to mark its chairs for specific seating arrangements during a big start-of-semester photo moment. The result? The chairs, quite clearly, looked like the flag of Japan.

When netizens saw the arrangements (the design was actually meant to spell out “WHU” and the founding year “1893” using students wearing different colored shirts), it quickly erupted into a major controversy (dubbed “The Wuhan Uni Chair Incident” / 武大椅子事件).

While some conspiracies point to supposed pro-Japanese sentiments among Wuhan Uni staff, it’s more probable that someone was simply blindsided by the chore of getting hundreds of students into the right spots.

The university has since apologized for the lack of oversight. But the incident taps into broader public frustration, especially following an earlier scandal involving a female student who accused a male student of sexual harassment — claiming he had indecently touched himself in front of her at the school library. Wuhan Uni issued the male student a demerit, but it later emerged that he was not acting indecently at all: he suffers from a chronic rash near the crotch area, and had simply been scratching himself.

The university will definitely be paying more attention from now on. Whether it’s about red stickers or itchy crotches, another controversy won’t do its reputation much good.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed the last newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know. No longer wish to receive these newsletters? You can unsubscribe at any time while remaining a premium member.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Travel

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Did tents defeat China’s hotel industry during the National Day holiday?

Published

2 days agoon

October 15, 2025

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Now that China’s combined National Day and Mid-Autumn Festival holiday (国庆 + 中秋) has ended, social media has seen a surge in discussions about major 2025 travel trends. According to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, a lucky total of 888 million domestic trips were made during the eight-day holiday.

While many Chinese cities and regions focused on offering innovative experiences — from lantern festivals to street performances — to attract travelers, there was also a grassroots trend that stood out.

Especially among the 18-35 age group, more Chinese are now choosing tents over hotels. On October 10, Business Times China (财经时报) featured an article about how ‘tents’ are putting a ‘dent’ into China’s hotel industry (title: “Did Tents Defeat the Hotel Industry during the National Day Holiday? 这个十一假期,打败酒店行业的是帐篷”).

Over recent years, as domestic travel has boomed, hotel prices in China have skyrocketed during holiday periods, with rates often doubling or tripling. For many—particularly younger travelers—this has made trips less affordable and less worthwhile. (Average nightly prices for mid- to high-end hotels in major cities exceeded 800 RMB / $112 this season.)

So what are we seeing now?

🔸 People are looking for alternative overnight stays, even though some hotels have lowered their prices in light of disappointing bookings.

🔸 Bathhouses are one example: many bathhouses or spas in China have become all-in-one leisure complexes combining hot springs, saunas, massages, dining, entertainment, and overnight lodging—becoming a new competitor for hotels (dubbed 洗浴旅游, “bathhouse tourism”).

Luxury bathhouses aren often opened 24/7 and have come a popular destination among young travelers.

🔸 Tents are growing in popularity. The outdoor equipment industry is seeing explosive growth in China, and Business Times China connects this growth to consumer backlash against unreasonable prices and poor service in Chinese hotels, seeing a future for more luxury camping models.

🔸 But it’s not just luxury camping. Many netizens across China have shared videos of travelers setting up tents and sleeping outdoors by roadsides or in scenic spots. Not only are people enthusiastic about outdoor camping and the experience itself, they also see it as a “consumption awakening” (消费觉醒), where younger generations are not willing to blindly pay ten times more for one night in a hotel than the purchase of a tent.

🔸 Another term that has been popping up more frequently is “Tangping Travel” (躺平式旅游). Tangping means “lying flat,” a phrase often used by young Chinese who “lie flat” as a way to cope with social pressure and competitive stress (read more). Unlike previous travel trends, where “special forces travelers” would rush to clock in at as many destinations as possible in a short time, tangping travel — whether in bathhouses, hotels, or tents — is about doing as little as possible, reflecting a shift away from hectic travel schedules.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

House of Wahaha: Zong Fuli Resigns

In the year following her father’s death, Zong Fuli dealt with controversy after controversy as the head of Chinese food & beverage giant Wahaha.

Published

3 days agoon

October 14, 2025

It’s a bit like a Succession-style corporate drama 🍿.

Over the past few years, we’ve covered stories surrounding Chinese beverage giant Wahaha (娃哈哈) several times — and with good reason.

Since the passing of its much-beloved founder Zong Qinghou (宗庆后) in March 2024, the company has been caught in waves of internal turmoil.

Some context: Wahaha is regarded as a patriotic brand in China — not only because it’s the country’s equivalent of Coca-Cola or PepsiCo (they even launched their own cola in 1998 called “Future Cola” 非常可乐, with the slogan “The future will be better” 未来会更好), but also because its iconic drinks are tied to the childhood memories of millions.

Future Cola by Wahaha via Wikipedia.

There’s also the famous 2006 story when Zong Qinghou refused a buyout offer from Danone. Although the details of that deal are complex, the rejection was widely seen as Zong’s defense of a Chinese brand against foreign takeover, contributing to his status as a national business hero.

After the death of Zong, his daughter Zong Fuli, also known as Kelly Zong (宗馥莉), took over.

🔹 But Zong Fuli soon faced controversy after controversy, including revelations that Wahaha had outsourced production of some bottled water lines to cheaper contractors (link).

🔹 There was also a high-profile family inheritance dispute involving three illegitimate children of Zong Qinghou, now living in the US, who sued Zong Fuli in Hong Kong courts, claiming they were each entitled to multi-million-dollar trust funds and assets.

🔹 More legal trouble arrived when regulators and other shareholders objected to Zong Fuli using the “Wahaha” mark through subsidiaries and for new products outside officially approved channels (the company has 46% state ownership).

⚡️ The trending news of the moment is that Zong Fuli has officially resigned from all positions at Wahaha Group as chairman, legal representative, and director. She reportedly resigned on September 12, after which she started her own brand named “Wa Xiao Zong” (娃小宗). One related hashtag received over 320 million views on Weibo (#宗馥莉已经辞职#). Wahaha’s board confirmed the move on October 10, appointing Xu Simin (许思敏) as the new General Manager. Zong remains Wahaha’s second-largest shareholder.

🔹 To complicate matters further, Zong’s uncle, Zong Wei (宗伟), has now launched a rival brand — Hu Xiao Wa (沪小娃) — with product lines and distribution networks nearly identical to Wahaha’s.

As explained by Weibo blogger Tusiji (兔撕鸡大老爷), under Zong Qinghou, Wahaha relied on a family-run “feudal” system with various family-controlled factories. Zong Fuli allegedly tried to dismantle this system to centralize power, fracturing the Wahaha brand and angering both relatives and state investors.

Others also claim that Zong had already been engaged in a major “De-Wahaha-ization” (去娃哈哈化) campaign long before her resignation.

In August of this year, Zong gave an exclusive interview to Caijing (财经) magazine where she addressed leadership challenges and public controversies. In the interview, Zong spoke more about her views on running Wahaha, advocating long-term strategic growth over short-term results, and sharing her determination to not let controversy distract her from business operations. That plan seems to have failed.

While Chinese netizens are watching this family brand war unfold, many are rooting for Zong after everything she has gone through – they feel her father left her in a complicated mess after his death.

At the same time, others believe she tried to run Wahaha in a modern “Western” way and blame her for that.

For the brand image of Wahaha, the whole ordeal is a huge blow. Many people are now vowing not to buy the brand again.

As for Zong’s new brand, we’ll have to wait for the next episode in this family company drama to see how it unfolds.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

House of Wahaha: Zong Fuli Resigns

How the “Nexperia Incident” Became a Mirror of China–Europe Tensions

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

Nanchang Crowd Confuses Fan for Knife — Man Kicked Down and Taken Away

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Rising Online Movement for Smoke-Free Public Spaces in China

China Trend Watch: Pagoda Fruit Backlash, Tiananmen Parade Drill & Alipay Outage (Aug 11–12)

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral3 months ago

China Memes & Viral3 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature12 months ago

China Books & Literature12 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral10 months ago

China Memes & Viral10 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained