China Media

No Hashtags for Mahsa Amini on Chinese Social Media

“Why is that every time Mahsa Amini is mentioned, it somehow gets linked to America?”

Published

3 years agoon

While the death of Mahsa Amini and the unrest in Iran is a major news story worldwide, the incident and its aftermath received relatively little attention in Chinese media, where the narrative is more focused on how Western responses to the issue are intensifying anti-American sentiments within Iran.

Her name in Chinese is written as 玛莎·阿米尼, Mǎshā Āmǐní. Mahsa Amini is the young Iranian woman whose death made international headlines this month and triggered social unrest and fierce protests across Iran for the past ten days, killing at least 41 people.

The 22-year-old Amini was arrested by morality police in Tehran on 16 September for allegedly not wearing her hijab according to the mandatory dress code for women while she was visiting the city together with her family. According to eyewitness accounts, Amini was severely beaten by officers before she collapsed and was taken to the hospital where she died three days later.

The protests following Amani’s death were visible in the streets, but also on social media where Iranian women posted videos of themselves cutting off their hair as a sign of mourning and protest, asking others to help raise awareness on Amini’s death and violence against women amid internet shutdowns in the country.

There were also protests outside of Iran in other places across the world. In London, protesters clashed with police officers during a demonstration outside the Iranian embassy on Monday.

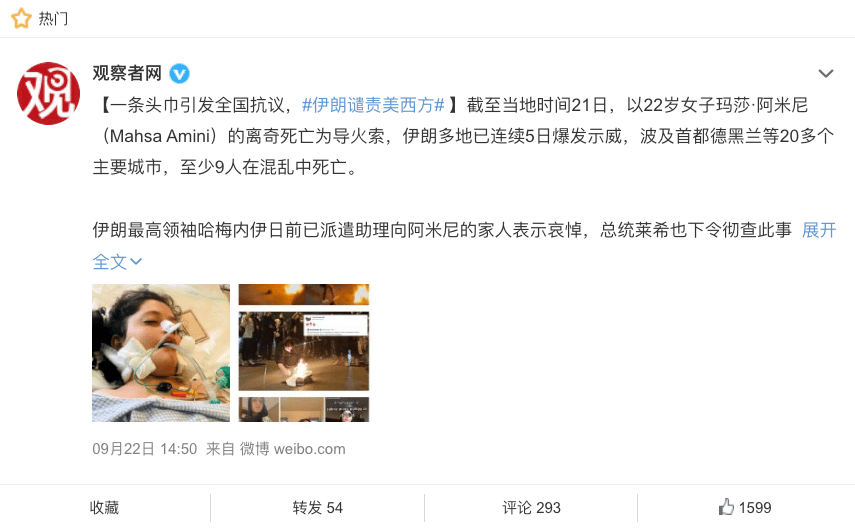

On Chinese social media platform Weibo, Chinese news site The Observer (观察者网) reported Amini’s death and the ensuing protests on September 22, but the hashtag selected to highlight the post did not focus on Amini.

Instead, it emphasized the reaction of the Iranian Foreign Ministry, which accused the United States and other Western countries of using the unrest as an opportunity to interfere in Iran’s internal affairs (hashtag: “Iran Denounces the US and other Western Countries #伊朗谴责美西方#).

The hashtag decision is noteworthy and also telling of how the developments in Iran have been reported by Chinese (online) media sources, which evade the topic of anti-government protests and instead focus on pro-regime marches and anti-American sentiments.

On China’s Tiktok, Douyin, as well as on Weibo, the Chinese media outlet iFeng News posted a video showing Iranian pro-government, anti-American protests on September 25, featuring interviews with veiled women speaking out in support of their country and showing “down with America” slogans and people burning the American flag.

In the comment sections, however, people were critical. One of the most popular comments said: “It must have been difficult organizing all these people.” Another person wrote: “Ah now I am starting to understand that it must have been Americans who beat the girl to death for not properly wearing her hijab.”

But there were also Chinese netizens who said that Iran was seeing a “color revolution” (颜色革命) initiated by the West, suggesting that foreign forces, mainly the U.S., are trying to get local people to cause unrest through riots or demonstrations to undermine the stability of the government.

China Daily also published a video on Douyin in which they featured Iranian political analyst Foad Izadi who said that the demonstrators in Iran could be divided into two groups: one group cared about “a young woman losing her life,” but a second group are people “linked to terrorist organisations based outside Iran.”

Chinese media commentator Zhao Lingmin (赵灵敏) posted a video in which she spoke about the situation in Iran and provided more background information on the history of the country, during which she noted how one Iranian official had supposedly said that “the only two civilizations in Asia worth mentioning are Iran and China.”

Zhao explained how Iran officially became the Islamic Republic in April of 1979 as 98.2% of the Iranian voters voted for the establishment of the republic system in a national referendum.

Videos using the Douyin hashtag “Iran’s Amini” (#伊朗阿米尼) were seemingly taken offline while various images included in Weibo posts about Mahsa Amini and the unrest in Iran were also censored.

“It’s good that we can follow the situation here [on this account], because it’s been removed at others,” one commenter said in response to one post about the many protests following the young woman’s death.

Searches for Amini’s name came up with zero results on the website of Chinese state media outlets CCTV and Xinhua, where the last article about Iran was about how Iranian people think “America can’t be trusted.”

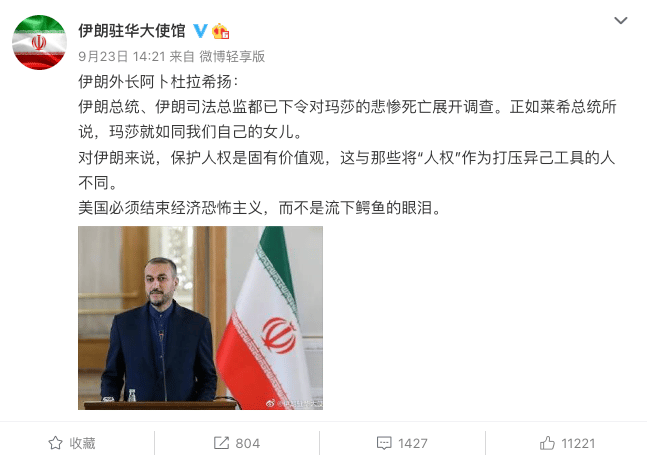

The official Weibo account of the Iranian Embassy in China did post a statement about Amini on September 23, writing that Iranian authorities have ordered an investigation into her tragic death and that the protection of human rights is an intrinsic value to Iran, “unlike those who use ‘human rights’ as a tool to suppress others.” “America must end its economic terrorism instead of shedding crocodile tears,” the last line said. That post received over 11,000 likes.

“Why is that everytime the Mahsa incident is mentioned, it somehow gets linked to America?!” one popular comment said, with another person also responding: “Sure enough, the U.S. gets blamed for everything.”

“So it was the Americans who killed her?” some Chinese netizens sarcastically wrote in response to the post by The Observer, which also mentioned the U.S. in their report of Mahsa’s death.

“I don’t know the exact circumstances, but I support the right of women not to wear a veil,” others said. “Men and women are equal, women should have the freedom to wear what they want and have education and get a job and have some fun,” another Weibo commenter wrote.

One Zhejiang-based Weibo user wrote: “The courage of people marching in the streets for freedom is moving. I wish that women will no longer have their freedom restricted through a hijab. What will the 21st century look like? The answer is still blowing in the wind.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our weekly newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

From China’s first soap opera Yearnings to the rise of AI-fueled nostalgia.

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 2, 2025

The year is 1990, and the streets of Beijing’s Fangshan District are eerily quiet. You can almost hear a pin drop in the petrochemical town, as tens of thousands of workers and their families huddle around their televisions, all tuned to the same channel for something groundbreaking: China’s very first soap opera, Yearnings (渴望 Kěwàng).

Yearnings tells the story of Liu Huifang (刘慧芳), a female factory worker from a traditional working-class family in Beijing, and her unlikely marriage to university graduate Wang Husheng (王沪生), who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Liu finds an abandoned baby girl, she adopts her and raises her as her own, against her husband’s wishes.

The couple is unaware that the foundling is actually the illegitimate child of Wang’s snobbish sister, Yaru. After Liu and Wang have a biological son, the marriage comes under further pressure, eventually leading to divorce. Liu is left as a single mother, raising two children on her own.

Still from Yearnings, via OurChinaStory.

Drawing inspiration from foreign dubbed television shows, Yearnings was produced as China’s first truly domestic, long-form indoor television drama. Spanning 50 episodes, the series traces a timeline from the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s through to the late 1980s—one of the most turbulent periods in modern Chinese history.

Before the series aired nationally on CCTV and achieved record viewership, the first station to air Yearnings in the Beijing region was the Yanshan Petrochemical TV Station (燕山石化电视台), China’s first major factory TV station (厂办电视台) located in Fangshan District.

Here, in this town of over 100,000, Yearnings garnered an astonishing and unprecedented 98% audience share. The series was truly groundbreaking and became a national sensation—not just because it was China’s first long-form television drama, or because it was a locally produced drama that challenged the long-standing monopoly of state broadcaster CCTV, but because Yearnings marked a major shift in television storytelling.

Until then, Chinese TV stories had always revolved around communist propaganda, or featured great heroes of the revolution. Yearnings, on the other hand, was devoid of political content and focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary people and their everyday struggles—love, desire, marital tension, single motherhood—topics that had never before been so openly portrayed on Chinese television.

The show’s creators had perfectly tapped into what was changing: the Communist Party was slowly withdrawing from private life, and people were beginning to see themselves less defined by their work unit and more by their home life—as consumers, as partners and parents, as citizens of a new China filled with aspirations for the future. Yearnings’ storyline was a reflection of that.

Chinese-Style “Nostalgia Core”

Yearnings marked a cultural turning point, coinciding with the rapid spread of TV sets in Chinese households. In 1992, economic reforms triggered a new era in which Chinese media became increasingly commercialized and thriving, before the arrival of the internet, social media, and AI tools once again changed everything.

Today, Yearnings still is a topic that often comes up in Chinese online media. On apps like Douyin, old scenes from Yearnings are reposted and receive thousands of shares.

📌 It’s emblematic of a broader trend in which more netizens are turning to “nostalgia-core.” In Chinese, this trend is known as “中式梦核” (Zhōngshì Mènghé), which literally means “Chinese-style dreamcore.”

Dreamcore is an internet aesthetic and visual style—popular in online communities like Tumblr and Reddit—that blends elements of nostalgia, surrealism, and subconscious imagery. Mixing retro images with fantasy, it evokes a sense of familiarity, yet often feels unsettling and deserted.

The Chinese-style dreamcore (中式梦核), which has become increasingly popular on platforms like Bilibili since 2023-2024, is different from its Western counterpart in how it incorporates distinctly Chinese elements and specifically evokes the childhood experiences of the millennial generation. Content tagged as “Chinese-style dreamcore” on Chinese social media is often also labeled with terms like “nostalgia” (怀旧), “childhood memories” (童年回忆), “when we were little” (小时候), and “Millennial Dream” (千禧梦).

According to the blogging account Yatong Local Life Observer (娅桐本地生活观察), the focus on the millennial childhood can be explained because the formative years of this generation coincided with a decade of rapid social change in China —leaving little in today’s modern cities that still evokes that era.

🌀 Of course, millennials in the West also frequently look back at their childhood and teenage years, particularly the 1980s and 1990s—a trend also embraced by Gen Z, who romanticize these years through media and fashion. In China, however, Gen Z is at the forefront of the “nostalgia-core” trend, reflecting on the 1990s and early 2000s as a distant, almost dreamlike past. This sense of distance is heightened by China’s staggering pace of transformation, modernization, and digitalization over the past decades, which has made even the recent past feel remote and irretrievable.

🌀 Another factor contributing to the trend is that China’s younger generations are caught in a rat race of academic and professional competition, often feeling overwhelmed by the fast pace of life and the weight of societal expectations. In this high-pressure environment—captured by the concept of “involution” (内卷)—young people develop various coping mechanisms, and digital escapism, including nostalgia-core, is one of them. It’s like a cyber-utopia (赛博乌托邦).

🌀 Due to the rise of AI tools available to the general public, Chinese-style nostalgia core has hit the mainstream because it’s now possible for all social media users to create their own nostalgic videos and images—bringing back the 1990s and early 2000s through AI-generated tools, either by making real videos appear more nostalgic or by creating entirely fictional videos or images that recreate scenes from those days.

So what are we seeing? There are images and videos of stickers kids used to love, visuals showing old classrooms, furniture, and children playing outside, accompanied by captions such as “we’re already so far apart from our childhood years” (example).

Images displayed in Chinese Dreamcore.

And notably, there are videos and images showing family and friends gathering around those old big TVs as a cultural, ritualized activity (see some examples here).

Stills from ‘nostalgia core’ videos.

These kinds of AI-generated videos depict a pre-mobile-era family life, where families and communities would gather around the TV—both inside and outside—from classrooms to family homes. The wind blows through the windows, neighbors crack sunflower seeds, and children play on the ground. Ironically, it’s AI that is bringing back the memories of a society that was not yet digitalized.

Nowadays, with dozens of short video apps, streaming platforms, and livestream culture fully mainstream in China—and AI algorithms personalizing feeds to the extreme—it sometimes feels like everyone’s on a different channel, quite literally.

In times like these, people long for an era when life seemed less complicated—when, instead of everyone staring at their own screens, families and neighbors gathered around one screen together.

There’s not just irony in the fact that it took AI for netizens to visualize their longing for a bygone era; there’s also a deeper irony in how Yearnings once represented a time when people were looking forward to the future—only to find that the future is now looking back, yearning for the days of Yearnings.

It seems we’re always looking back, reminiscing about the years behind us with a touch of nostalgia. We’re more digitalized than ever, yet somehow less connected. We yearn for a time when everyone was watching the same screen, at the same time, together, just like in 1990. Perhaps it’s time for another Yearnings.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Sources (other sources included in hyperlinks)

Koetse, Manya. 2016. “From Woman Warrior to Good Wife – Confucian Influences on the Portrayal of Women in China’s Television Drama.” In Stefania Travagnin (ed), Religion and Media in China. New York: Routledge.

Rofel, Lisa B. 1994. Yearnings: Televisual Love and Melodramatic Politics in Contemporary China. American Ethnologist 21(4):700-722.

Wang, Dan (汪丹). 2018. “《渴望》的艺术价值” [The Artistic Value of Yearnings].” Originally published in Beijing Daily (北京日报), October 12, 2018. Reprinted in Digest News (文摘报), October 20, 06 edition. Also see Sohu: 当年红遍大江南北的《渴望》.

Wang Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, a Chinese television soap opera with a message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Zhuge Kanwu. 2021. “重温1990《渴望》:苦得“刘慧芳”希望被导演写“死” [Revisiting 1990’s Yearnings: The Suffering Liu Huifang Hoped to Be Written Off by the Director]. Zhuge Dushu Wu (诸葛读书屋), January 22. https://wapbaike.baidu.com/tashuo/browse/content?id=b699ee532cf79f862bfa14ad.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

From historic speeches to trending slogans, this is China’s official media response to the US tariff escalation.

Published

3 months agoon

April 13, 2025

What do Mao’s 1953 Korean War speech and Yang Jiechi’s 2021 Alaska Summit remarks have to do with the escalating US–China trade war? In Chinese official media responses, history and emotionally charged rhetoric are used to clearly signal China’s stance and boost national confidence. Here, we explore three dominant narratives.

As you probably know by now, April 9 marked “D-Day” for Trump’s rollout of steep tariffs. On Chinese social media, the escalating trade war between China and the US dominated conversation, especially on that “D-Day Wednesday,” when nearly all of Weibo’s top 10 most-viewed hashtags were related to Trump’s tariffs and China’s retaliation.

Since developments are unfolding rapidly, here’s a quick recap:

- 🇺🇸💥 On Wednesday, April 2, President Trump announced steep new tariffs, including a universal 10% “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods, and an additional 34% reciprocal tariff specifically targeting China as part of the so-called “Liberation Day,” set to begin on April 9. Combined with pre-existing tariffs, this would bring the total tariff rate on Chinese goods entering the United States to over 54%.

- 🇨🇳⚔️On Friday, April 4, China’s State Council Customs Tariff Commission Office issued an announcement stating that, starting April 10, an additional 34% tariff would be levied on all imported goods originating from the United States, on top of existing tariff rates.

- 🇺🇸⚔️On Tuesday, April 8, Trump vowed to increase tariffs on Chinese exports by an additional 50% if Beijing would not withdraw its 34% counter-tariffs.

- 🇨🇳💥On Wednesday, April 9, China’s finance ministry announced it would further raise tariffs on US goods to 84% starting the following day, in retaliation for the newly imposed 104% tariff on Chinese goods.

- 🇺🇸💣On Wednesday, April 9, Trump then did a U-turn and halted the new steep tariffs for dozens of countries for 90 days, except for China, followed by yet another threat of an additional 21%, bringing those import taxes to 125%.

- 🇺🇸🚨On Thursday, April 10, it was clarified by the White House that tariffs on China would actually total 145%, combining the previously announced 125% with a 20% import tax levied for fentanyl smuggling.

- 🇨🇳💣On Friday, April 11, Chinese official channels reported that China would adjust its tariff measures on important goods from the US starting April 12, raising the rate from 84% to 125%. A related hashtag became no 1 trending topic on Weibo, where it received over 500 million views by Friday night (#对美所有进口商品加征125%关税#).

- 🇺🇸⬅️ On Friday, April 11, Trump’s administration announced that it will exempt smartphones, computers and some other electronic devices from the new tariffs, including the 125% levies imposed on Chinese imports (#特朗普政府再度退缩#; #美国免除智能手机电脑对等关税#).

There are hundreds of hashtags and trending topics circulating across Chinese platforms — from Weibo to Toutiao, from Kuaishou to Douyin — related to the latest developments in the US–China trade war. The topic is super popular, but censored comment sections and removed images also reveal just how sensitive it can be at times.

The biggest hashtags and slogans are those initiated and amplified by official channels. From press conferences to hashtags and visual propaganda, you can see a clear strategic media narrative that draws on history, national pride, and patriotism to frame recent developments, mobilize public sentiment domestically, and show China’s resilience to the rest of the world.

Here, I’ll highlight three hashtags that have recently become top trending, each representing a different kind of official narrative or rhetoric in response to the ongoing developments.

1. China Won’t Back Down

(China will see it through to the end #美方一意孤行中方必将奉陪到底#)

The message that China will not be intimidated by the US is one that echoes across Chinese social media these days, reinforced by official channels.

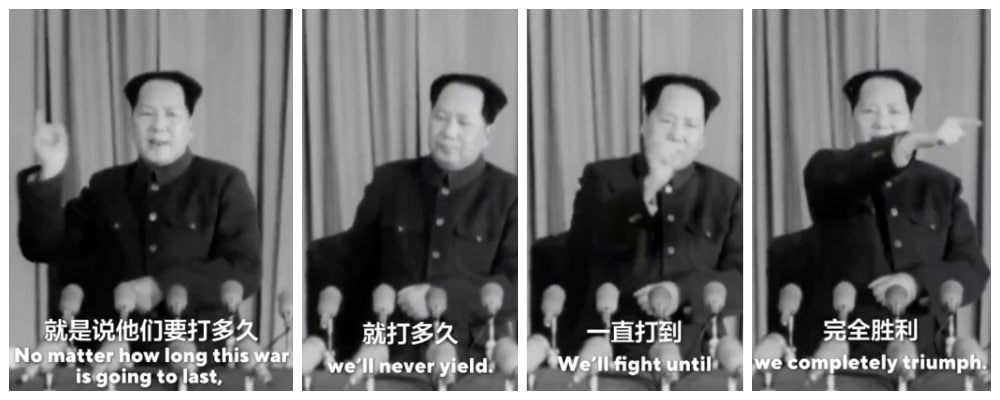

On April 9, the Weibo account of Chinese media outlet Guancha (@观察者网) and the state-run New Era China Foreign Affairs Think Tank (@新时代中国外交思想库) posted a video showing part of a speech given by Mao Zedong on February 7, 1953, during the final stages of the Korean War at the 4th Session of the 1st National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).

In the short fragment, Mao Zedong says:

🇨🇳📢 “As to how long this war will last, we are not the ones who can decide. It used to depend on President Truman, and it will depend on President Eisenhower, or whoever becomes the next US President. It’s up to them. No matter how long this war is going to last, we’ll never yield. We’ll fight until we completely triumph.”

The 1953 speech by Mao was also posted on the US social media platform X by Mao Ning (@毛宁), spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The video was then also spread by blogging accounts and regular netizens. History blogger Zijin Gongzi (@紫禁公子), who has over 435k fans on Weibo, reposted the video, writing:

💬 “Our forefathers never bowed their heads to strong enemies. How could we easily accept defeat? (..) We must not lose this spirit, we must let everyone know that we have a strong backbone and will never bow down.”

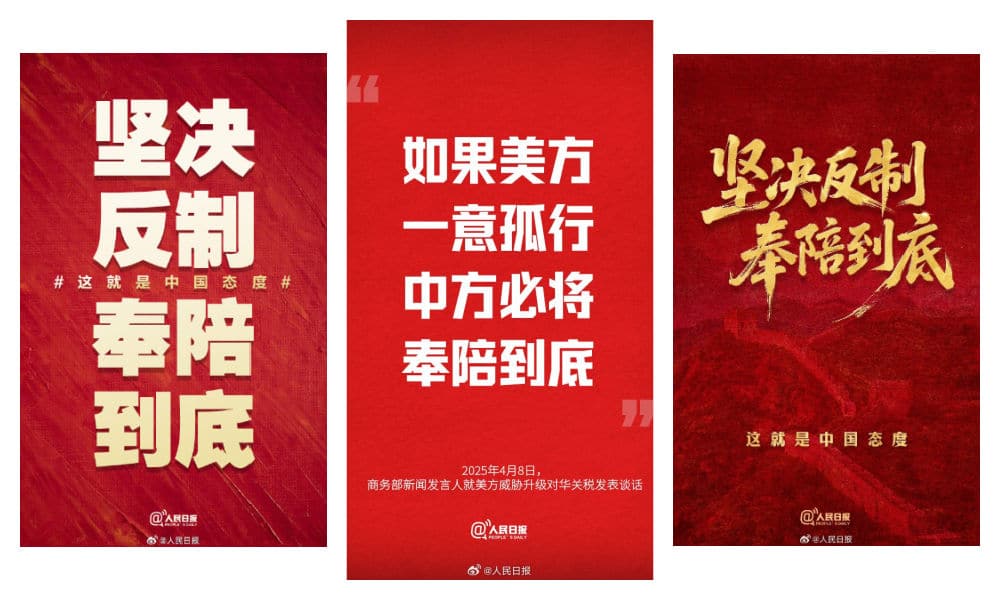

Together with the Mao video, the hashtag used by the Think Tank and many other Chinese media accounts, such as People’s Daily (@人民日报), is “If the US obstinately clings to its course, China will fight to the end [lit. accompany them to the end]” (#美方一意孤行中方必将奉陪到底#) and “fight to the end” (#我们奉陪到底#).

These phrases in part come from a press conference given by Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) on April 8. Here, he said:

🇨🇳📢 “I want to emphasize once again that there are no winners in trade wars and tariff wars, and protectionism is no way forward. The Chinese people do not provoke trouble, but they are also not afraid. Pressure, threats, and blackmail are not the proper ways to deal with China. China will inevitably take necessary measures and resolutely safeguard its legitimate rights and interests. If the American side disregards the interests of both countries and the international community and insists on waging a tariff war and trade war, China will fight to the end [lit. inevitably accompany them to the end 中方必将奉陪到底].”

The next day, these words had been turned into digital propaganda posters, with some slight variations in the phrases used. One People’s Daily graphic underlined: “We resolutely take countermeasures, and follow through until the end (坚决反制 奉陪到底),” accompanied by the line: “This is China’s attitude,” which was also turned into a hashtag (#这就是中国态度#).

2. This Is No Way to Deal with China

(Chinese people aren’t buying it #中国人从来不吃这一套#)

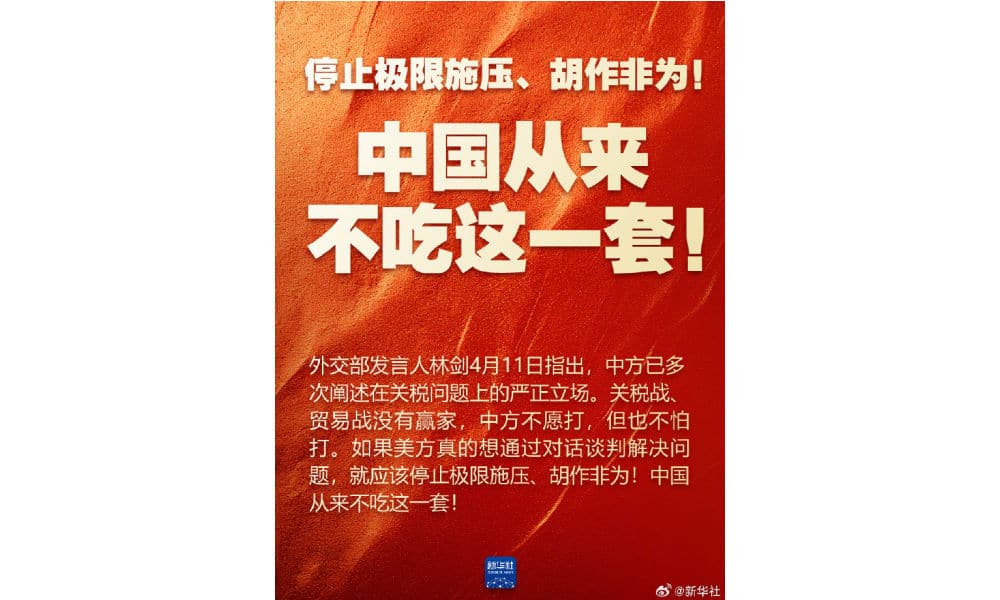

Another related yet somewhat different sentiment that dominates Chinese social media—led by official channels—is that China is not only rejecting the trade games played by the US, but is also distancing itself from the American playbook. The message is: this is no way to deal with China. This narrative, and the hashtag surrounding it, emerged slightly later than the first. While the earlier phrase about China not backing down trended as China matched the US in its tariff measures, this one took off with China’s final blow—raising the rate on US imports from 84% to 125% in response to the latest US tariff hikes.

The April 11 statement on the Ministry of Finance website (财政部网站), also posted on Weibo by Xinhua News (@新华社), announced that China would adjust its additional tariff measures on imports originating from the United States effective April 12. It also stated that China strongly condemns the US imposition of excessively high tariffs and will no longer engage in further tariff escalations:

🇨🇳📢 “Given that, at the current tariff level, US goods entering China effectively have no market viability, if the US continues to raise tariffs on Chinese exports to the US, China will no longer respond.”

The main hashtag used by Xinhua and many other media channels is “中国从来不吃这一套” (Zhōngguó cónglái bù chī zhè yī tào), which can be translated as: “The Chinese people have never accepted this,” or more colloquially, “We’re not buying it.”

The phrase initially became popular in 2021, after it was used by China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi (杨洁篪) during the first major strategic talks of the Biden administration, held in Anchorage on March 19. Due to the occasionally heated exchanges between the two delegations, some called the Alaska talks a “diplomatic clash.”

Yang Jiechi during the Alaska Summit

At the time, Yang delivered a lengthy statement to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, stressing that Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang are “inseparable parts of China,” and that China strongly opposes US interference in its internal affairs. Suggesting the US should focus more on its own human rights issues and racial problems instead of lecturing China, he added the now-famous line: “The US is not qualified to speak to China from a position of strength. The Chinese people don’t buy that” (美国没有资格居高临下同中国说话,中国人不吃这一套).

The phrase quickly went viral—boosted by state media, celebrated by netizens, and turned into a marketing slogan. It now appears on t-shirts, teacups, phone cases, and other patriotic merchandise.

The translation of the phrase still triggers discussions. While merchandise typically translates it as “Stop interfering in China’s internal affairs,” that’s not an accurate translation. During the Alaska Summit, interpreter Zhang Jing (张京) (who gained viral fame at the time) translated it in real-time as “This is not the way to deal with the Chinese people.” However, some commentators and professional translators argued this was a missed opportunity to take a tougher stance, as the Chinese phrase is much sharper and could be loosely translated as: “We Chinese people don’t swallow this crap.”

In Alaska, Yang emphasized that dealing with China requires mutual respect, and that history will prove that trying to strangle China’s rise would ultimately hurt the US itself (“与中国打交道,就要在相互尊重的基础上进行。历史会证明,对中国采取卡脖子的办法,最后受损的是自己。”)

Similar sentiments now dominate online media discourse in China. The slogan has evolved from “The Chinese people don’t buy this” (中国人不吃这一套) to the more authoritative “China has never bought this” (#中国从来不吃这一套#)

Adding fuel to this message are hashtags like “America’s repeated imposition of excessively high tariffs on China has become a joke” (#美方对华轮番加征畸高关税已沦为笑话#).

Ridiculing America (especially Trump) has become a popular pastime on Chinese social media this past week, with a flood of Chinese and international memes circulating widely.

Especially popular are memes mocking the idea of America as a future “Made-in-America” manufacturing hub, the irony of iconic American products (like MAGA hats) being made in China, and how everyday essentials such as eggs have reached historic price highs in the US (a crisis partly caused by bird flu but now worsened by the tariffs).

On April 13, the hashtag “The 145% tariff makes one panda plush toy cost 80 dollars” (#145%关税让1只熊猫玩偶卖80美元#) also went trending, sparking jokes about how even the most trivial things could suddenly become luxuries in the US.

3. China is the Most Stabile Superpower

(Countering America’s madness with China’s stability #以中国稳应对美国疯#)

A third stance that has been dominant in Chinese official online discourse is that China’s development does not rely on anyone’s favors (#中国发展从不靠谁的恩赐#, derived from a quote by Xi Jinping), and that despite the US’s measures, China’s rise on the world stage cannot be stopped. In fact, the narrative suggests that these actions by the US are only accelerating China’s ascent.

A commentary piece published by state broadcaster CCTV (@央视新闻) on April 11 quoted Professor Li Haidong (李海东) of China Foreign Affairs University, who stated that the US’s increasingly aggressive behavior reinforces the notion that it is using tariffs as a tool of extreme pressure; as a weapon to serve its own interests. According to Li, this reflects America’s hegemonic mindset, aiming to assert superiority by intentionally creating crises.

But rather than strengthening the US, the commentary argues, these recent measures are backfiring and are damaging the US’s domestic economy and undermining its global credibility.

In contrast to the US’s presumed recklessness and “hysterical approach,” China is depicted as a “responsible world leader,” bringing certainty to an uncertain world by “responding with its own stability” and proving to be, supposedly, a more reliable engine of global growth. The commentary states:

🇨🇳📢 “As the tariff storm strikes, China is using its own ‘stability’ to resist the trials and tribulations, by upholding rules, defending justice, and steering the big ship of globalization through treacherous countercurrents, toward the right path of openness and cooperation.”

To promote the piece on social media, CCTV used the hashtag “Responding to America’s madness with China’s stability” (#以中国稳应对美国疯#).

This sentiment was echoed by nationalist bloggers, such as Tangzhe Tongxue (@唐哲同学), who posted on April 13:

💬 “In this world, besides China, the rest are all just a poorly equipped small-town theater troupe (草台班子).”

The phrase “草台班子” (cǎotái bānzi) literally refers to a makeshift opera troupe performing on a shabby rural stage, and is used to describe an incompetent group of amateurs.

The blogger’s comment indirectly responds to comments made by US Vice President JD Vance, who defended Trump’s tariffs in a Fox News interview by saying: “To make it a little more crystal clear, we borrow money from Chinese peasants to buy the things those Chinese peasants manufacture.”

That remark sparked controversy online, with many netizens calling it ignorant. Some pointed out that Chinese people were already wearing fine silks when Westerners were still wrapped in animal skins fishing in the sea, and flipping the narrative to portray Americans as the real “country bumpkins.”

Meme shared online.

This sentiment was reinforced by another hashtag trending on Weibo on April 13: “You think we’re scared, but we actually don’t care” (#你以为我们scared其实我们不care#).

That line comes from a Channel 4 interview with Gao Zhikai (Victor Gao/高志凯), Vice President of the Center for China & Globalization (CCG), who stated:

🇨🇳📢 “China is fully prepared to fight to the very end. Because the world is big enough that the United States is not the totality of the market in the world. So if the United States wants to go in that direction of completely shutting itself out of the Chinese market, be my guest. [Interviewer: Yes and China will lose the US market..] We don’t care. We don’t care. China has been here for 5000 years, and for most of the time there was no United States and we survived. If the United States wants to bully China, we will deal with the situation without the United States. And we except to survive for another 5000 years.”

While this reflects the official position and is widely echoed across social media, others stress the importance of remembering history; particularly China’s “Century of Humiliation” (百年国耻), which was marked by war, aggression, and unequal treaties imposed by foreign powers. Just like other historical anniversaries, some bloggers argue that Trump’s tariff “D-Day,” April 9, should not be forgotten (“今天是每个中国人难以释怀的日子”) and that it marks another reason for China’s renewed rise.

In a video posted by CCTV’s short video platform Xiaoyang Shipin (小央视频) on April 13 (link), the narrator states:

🇨🇳📢 “The so-called global “beacon” now puts “America first.” It slaps allies in the face, treats the world with predatory practices, and makes other countries pay for MAGA, pushing the fragile word economy over the edge, and pitching itself against the whole world. With China here, the sky won’t fall. With around 5% economic growth, China adds the output of a mid-sized European economy every year. China has hundreds of millions of skilled workers. The Chinese people are well known for their strong work ethic. China’s development over the past seven decades is a result of self-reliance and hard work, not favors from others, (..) Global businesses believe the next China is still China and the best is yet to come (..) Markets need to restore faith. Between the pond of closed markets, and the ocean of economic interconnectivity, which one would you choose?”

Overall, packaged across different media — from hashtags to short videos, from press conferences to news reports, and from digital slogan posters to Ministry of Foreign Affairs tweets — China’s strategic political media messaging is clear and quite powerful, despite the fragile and censored environment it operates in: China is not afraid to strike back, China will lead with calm, and eventually, China will emerge as the winner. Whatever happens next remains to be seen, but when it comes to turning crisis into opportunity, China’s official media channels have already done just that.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: “THE US-CHINA TARIFF WAR ON CHINESE SOCIAL MEDIA“

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

Jiehun Huazhai (结婚化债): Getting Married to Pay Off Debts

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

Behind the Mysterious Death of Chinese Internet Celebrity Cat Wukong

Do You Know Who Li Gang Is? Anti-Corruption Official Arrested for Corruption

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

Earring Gate: Huang Yangdiantian and the 2.3 Million RMB Emerald Earrings

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Society10 months ago

China Society10 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoTeam China’s 10 Most Meme-Worthy Moments at the 2024 Paris Olympics

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoAbout Wang Chuqin’s Broken Paddle at Paris 2024

Mary

October 1, 2022 at 2:00 am

Im an Iranian . The things you probably dont know about Iran is that the anti American protest that you mentioned is completely designed and directed by regime and all of those veil women and bearded men are somehow connected to the regime if not actors and actresses . They are Basij and their families . You called them “people “ they are not people at all . i dont know any Iranian that has ever said down to America or burn their flags when we were kids they made us do this in school every morning these are all fake and forced . Iranian people have nothing against the west . You mentioned that you read the comments and … Today in Iran regime admitted that they have hired 8000 people for commenting on social media to their fake news and in advance scenarios . We Iranians got used to this method