China Society

Nobody’s Baby? Chinese Girl in Canceled Surrogacy Case Has No Birth Certificate, No Hukou

From surrogacy baby to ‘heihaizi’ – her biological parents canceled the surrogacy agreement, but she was born anyway.

Published

5 years agoon

The news story of a child born through surrogacy is the talk of the day on Weibo, leading to heated discussions on China’s ‘underground’ surrogacy practices.

The tragic story of a 3-year-old girl born through surrogacy is top trending on Chinese social media today, where the child is referred to as the ‘unregistered surrogacy girl’ (“黑户代孕女童”).

The child was meant to grow up with her two biological parents, but when the surrogate mother tested positive for a syphilis infection halfway through the pregnancy, the intended parents canceled the surrogacy agreement. The story was told in a short video report by Chinese news outlet The Paper.

The poverty-stricken surrogate mother ended up having the baby herself, but could not afford her bills and sold the baby’s birth certificate. The biological parents have refused to take responsibility for the girl.

Without her formal papers and household registration, the 3-year-old girl cannot go to school and is not registered anywhere.

From Surrogacy Baby to ‘Heihaizi’

On January 12, Chinese media outlet Time Weekly (时代周报) published a lengthy interview with the surrogacy mother recounting the entire story of the canceled surrogacy agreement.

The story starts in 2016 when the then 38-year-old* Wu Chuanchuan (吴川川, alias) became a surrogate mother as a way to earn money. The older couple who wanted a baby came from Inner Mongolia and had previously lost a child. *(In the interview, Wu claims she is actually younger than the age indicated on her official papers, which say she is now 47.)

The surrogacy agreement, arranged through an underground company, was settled at 170,000 yuan ($26,200). It concerned a gestational surrogacy, in which the child is not biologically related to the surrogate mother.

During the pregnancy, Wu was living together with other surrogate mothers. When she was four months pregnant, she unexpectedly tested positive for syphilis. Wu says she suspects that the infection was spread within the small surrogacy mother community she lived in.

Syphilis in pregnant women is risky and can have a major impact on the baby’s health. It can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, or death as a result of the infection as a newborn.

“The intended parents decided to withdraw from the surrogacy arrangement, asking for a refund and offering to pay for an abortion.”

Due to syphilis, the intended parents of the baby decided to withdraw from the surrogacy arrangement, asking for a refund and offering to pay for an abortion. Wu would only receive 20,000 yuan ($3085).

This situation left Wu, who already felt the fetus moving, in a very difficult situation. She eventually refused to terminate the pregnancy and withdrew from the surrogacy agency’s home.

Staying at cheap hotels in the city of Chengdu and unable to find a suitable adoption family, Wu eventually gave birth to a baby girl that she would raise herself.

But there was one major issue: money. Wu already could not afford the hospital admittance fee, let alone the 12,000 yuan ($1850) in hospital bills she had to pay after needing a C-section delivery.

To pay for her medical bills, Wu was forced to take desperate measures and ended up selling her baby’s birth certificate. Through the internet’s black market, she found someone who would pay 20,000 yuan ($3085) for it.

Once the baby was born, things looked up for Wu. She soon married a kind man who was willing to raise baby girl ‘Xiao Rang’ (小让, alias) together with her, and the child’s congenital syphilis was cured.

But Xiao Rang still had no birth certificate, and thus no hukou.

Wu and Xiao Rang, screenshot from The Paper video report.

The hukou or ‘household registration’ system is a registered permanent residence policy. A hukou is assigned at birth based on one’s community and family. China’s hukou system, amongst others, separates rural from urban citizens and is essential to access social services, including education and healthcare.

Without a hukou, the child cannot attend kindergarten, and will not be able to go to school – she will be a heihaizi (黑孩子, lit. ‘black child’), an ‘illegal child’ not registered anywhere.

In December of 2020, as reported by The Paper, Wu traveled from Chengdu to Inner Mongolia in search of her daughter’s biological parents.

The girl’s intended parents turned out to have twin sons now. They bought a house and went through the process to get their twins through another surrogate mother. After spending approximately 700,000 yuan ($108,000), the family allegedly could not afford to also be legally responsible for Xiao Rang. Afraid of the consequences, the 50-year-old biological father initially also seemed unwilling to formally arrange adoption papers for his daughter, Wu told Time Weekly.

Banned Baby Business

On Weibo, a hashtag page about Xiao Rang’s story received over 550 million views on Tuesday, making it one of the most-discussed topics on January 12 (#首个遭代孕客户退单女童无法上户#).

Due to the media attention, and the biological father’s identity being exposed, the case was still developing while Chinese netizens looked on.

According to the latest reports, Xiao Rang’s biological father will now provide assistance in arranging registration papers for the little girl while Wu Chuanchuan will still raise the child.

The fact that the father himself came forward to tell his side of the story also became a trending topic (#遭退单代孕女童生物学父亲现身#), garnering over 260 million views by Tuesday night Beijing time. The biological father confirms that they gave up on the baby once they were informed of Wu’s syphilis infection, and that they did not expect Wu to have the baby after all.

Meanwhile, on social media, there seems to have been a shift in sentiments regarding this story. Netizens initially sided with the surrogate mother and her tragic story.

But as the media continue to report on this story, more and more people are starting to doubt Wu’s sincerity, wondering if she used media exposure to portray herself as a victim to gain the public’s sympathy.

Online commenters criticize Wu for being part of the surrogacy agreement, for choosing to have the child despite her syphilis, and for selling the child’s birth certificate. Many call her ‘immoral’ and ‘irresponsible.’

“Surrogacy exploits women, and it is a serious violation of social ethics and morals. Taking part in surrogacy should be severely punished.”

Surrogacy has been a hot topic on Chinese social media recently. Just a month ago, a short film titled “10 Months With You” (‘宝贝儿’) by famous Chinese director Chen Kaige (陈凯歌) also stirred controversy for supposedly presenting surrogacy in China in a relatively positive light.

Screenshot from “10 Months With You” by Chen Kaige

The 30-minute film revolves around a young girl who signs a surrogacy contract with intended parents without telling her boyfriend. When she gets emotionally attached to the baby during her pregnancy, things get complicated. But she eventually is persuaded by her boyfriend that the child is not intended to be with them, after which she is willing to part with the baby.

Chinese state media outlets, including Global Times and China Daily emphasized that surrogacy is illegal in China and that those who take part in surrogacy will face fines or even criminal prosecution.

Nevertheless, the practice of surrogacy is a somewhat legislative grey area in China. China’s Ministry of Health introduced regulations in 2001 that made it illegal for medical staff to offer surrogacy services. In 2015, there were official plans to completely curb surrogate pregnancies. But that strict ban on surrogacy pregnancies was later reversed.

In 2017, People’s Daily even published a controversial article that suggested a loosening of surrogacy bans to boost China’s birth rates. Meanwhile, there have been ongoing reports about China’s booming underground surrogacy market (here, here ).

In 2018, state media outlet Global Times quoted Qiu Renzong, a bioethics expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Science in saying: “The Chinese government should consider setting some rules to allow surrogacy in certain circumstances.”

With discussions on Xiao Rang’s case and surrogacy in China being a major topic on Weibo, the legal side is also receiving much attention. Law expert Zhang San (@普法达人张三) uses the hashtag “Criminalize Surrogacy” (#建议代孕入刑#) when he writes:

“Although surrogacy is illegal, it is a blank space in the criminal law. Surrogacy exploits women, and it is a serious violation of social ethics and morals. Taking part in surrogacy should be severely punished. If the freedom is not restricted, it will surely lead to exploitation of the weak by the strong.”

Some people on Weibo argue that most of the people involved in Xiao Rang’s story are filthy and immoral, and that they need to be punished. But virtually everyone agrees that the little girl needs to be registered in order to still have a chance to lead a normal life: “The child is innocent.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2021 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Memes & Viral

Nanchang Crowd Confuses Fan for Knife — Man Kicked Down and Taken Away

An unfortunate misunderstanding led to one innocent man being the only person injured in a crowd of thousands.

Published

1 month agoon

October 5, 2025

On the evening of October 1st, National Day and the start of a week-long holiday, Nanchang was celebrating with a spectacular fireworks/drone show, drawing an enormous crowd of people (see video).

But the fireworks weren’t the only thing drawing attention. One man on Nanchang’s crowded Shimao Road caught bystanders’ eyes.

He was shirtless, strongly built with a visible tattoo, and was waving a pointed object while loudly shouting something that sounded like, “I’ll kill you! I’ll kill you!”

At first, the people around him seemed unsure of what to do, keeping their distance and too afraid to approach. A large crowd formed but stayed back.

Then, a brave young man in red rushed forward and snatched the pointed object from his hand, while another young man leapt in with a flying kick that knocked him to the ground.

Several others then joined in, working together to restrain the man, as onlookers surrounded the scene and held him there until police arrived and took him to the station.

Soon, videos of the incident spread online (see video here), and rumors quickly surfaced that the man had been trying to attack people with a knife.

But that all turned out to be one major misunderstanding.

The next day, local police clarified what had actually happened, followed by an explanation from the man himself.

The man in question, a 31-year-old local second-hand car dealer named Li, had come to see the fireworks together with his family, including his sisters and three nephews.

Because of the very hot weather, he had taken off his shirt and was cooling himself with a 10-yuan folding fan he had just bought along the way.

After the show, while walking back, Li realized one of his nephews was missing and searched for him, calling out in his local dialect: “Where’s my kid? Where’s my kid?” (“我崽尼 我崽尼” wǒ zǎi ní).

Bystanders misheard this as “我宰你 我宰你” (wǒ zǎi nǐ, wǒ zǎi nǐ, “I’ll kill you, I’ll kill you”) and mistook his folding fan for a machete.

Meanwhile, Li couldn’t understand why people around him were avoiding him and keeping their distance from him while he was searching for his nephew (see that moment here, also see more footage here). People were watching him, and recording the scene from a distance.

Before Li realized what was happening, the fan was snatched from his hands and he was violently kicked. A crowd swarmed him, beat him, and pushed him to the ground.

The police then detained him, and it wasn’t until the early hours of October 2, after thorough questioning, that he was finally released.

“I’m still confused about it,” Li said the next day. Holding the fan up to the camera, he asked: “Can a fan like this really scare people? I don’t understand — I just got beaten for nothing.”

Mr Li in his video, showing the fan he bought for 10RMB/$1.4 at the Nanchang fireworks.

Some commenters remarked that out of the 1.2 million people who were out in Nanchang that night, he was the only one injured.

Li seems to be doing ok apart from a sore backside and a puzzled mind, and his nephew apparently is also safe and well.

The bizarre misunderstanding has sparked widespread banter online, with people now referring to Li as “Nanchang Brother Fan” (南昌扇子哥).

“I’m dying of laughter. It’s both tragic and hilarious,” one Douyin user wrote, while others simply called the situation “so drama” (抓马 zhuāmǎ): “I’m not supposed to laugh, but I can’t help it.”

Some also noted that they understood why people at the scene mistook Li for a criminal: “At night, a guy with tattoos, holding a long stick-like object, shouting loudly all the way, what would you think?”

All joking aside, the public’s response on such a crowded night — when so many people gathered together, potentially making a tempting target for those with bad intentions — shows a heightened sense of vigilance. Unlike the U.S., where gun violence is more common, shootings are rare in China. But random stabbings have increasingly made headlines.

For Nanchang in particular, a stabbing incident that shocked the nation had taken place only weeks earlier: a 19-year-old woman was attacked and stabbed more than ten times by a 23-year-old man she did not know, and later died from her injuries.

But there have also been other recent cases, from Wuhan to Leiyang. And in 2024 especially, a spate of stabbing incidents shocked the country. In Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, a mass stabbing left eight people dead and 17 others injured.

The positive takeaway from this entire mix-up is that the quick action of the crowd — despite their wrong assessment of the situation — shows that people weren’t afraid to step in for the sake of public safety.

But others claim the exact opposite is true. Illustrator and commentator ‘Wu Zhiru’ (吴之如), former editor at Zhenjiang Daily, saw the incident as an example of toxic herd mentality. He posted an illustration of a fan being held up with the characters 清风徐来 (qīng fēng xú lái, “a cool breeze slowly blows”), an idiom to describe a pleasant atmosphere. A finger from the right points at the fan-holder, saying “Look, he’s gonna commit violence!” (“哇,他要行凶啦!”)

Wu Zhiru warns against panic-driven mob mentality and wonders why the first man, who snatched the “knife” from Li’s hands, did not stop the crowd from attacking Li as soon as he discovered that he had snatched away a fan and not a blade. Drawing historical parallels to the Cultural Revolution, Wu argues that people are sometimes so set on doing the “heroic” thing that they hesitate to correct misunderstandings once better information is available — a mindset that can lead to serious, harmful consequences.

For Li himself, despite the unfortunate night he had, the situation has actually brought him some unexpected fame and extra attention for his second-hand car dealership, which undoubtedly makes his boss happy (in a very recent livestream, Li was praised for being kind and loyal).

Many netizens also argued that the real lesson to draw from this ordeal is the importance of speaking proper standard Chinese. Some even framed the incident as “The Importance of Mandarin” (论普通话的重要性), pointing out that the whole problem began because Li was misunderstood while speaking dialect.

Image posted on Weibo in support of the “fan-waving brother.” The character on the fan says “tolerate.”

Others joked that the misunderstanding was just a grave injustice to shirtless men everywhere, writing: “From now on, the world has one less sincere guy who goes shirtless in the streets. He’ll never be the same again.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

China’s National Day Holiday Hit: Jingdezhen’s “Chicken Chop Bro”

From viral street food vendors to China’s donkey crisis and new eldercare services, here’s this week’s Weibo highlights in What’s on Weibo’s China Trend Watch.

Published

2 months agoon

September 30, 2025

🔥 What’s Trending in China This Week? Stay updated with China Trend Watch by What’s on Weibo — your quick overview of what’s trending on Weibo and across other Chinese social media, curated by Manya Koetse.

What’s inside:

- 1. Jingdezhen’s “Chicken Chop Bro” Becomes Nationwide Meme

- 2. China’s 2025 Golden Week Travel Trends

- 3. China Faces Donkey Shortage Crisis

- 4. Word of the Week: “Ride-hailing for Relatives” 亲属打车 Qīnshǔ Dǎchē

- 5. What’s Inside at a Glance

1. Jingdezhen’s “Chicken Chop Bro” Becomes Nationwide Meme

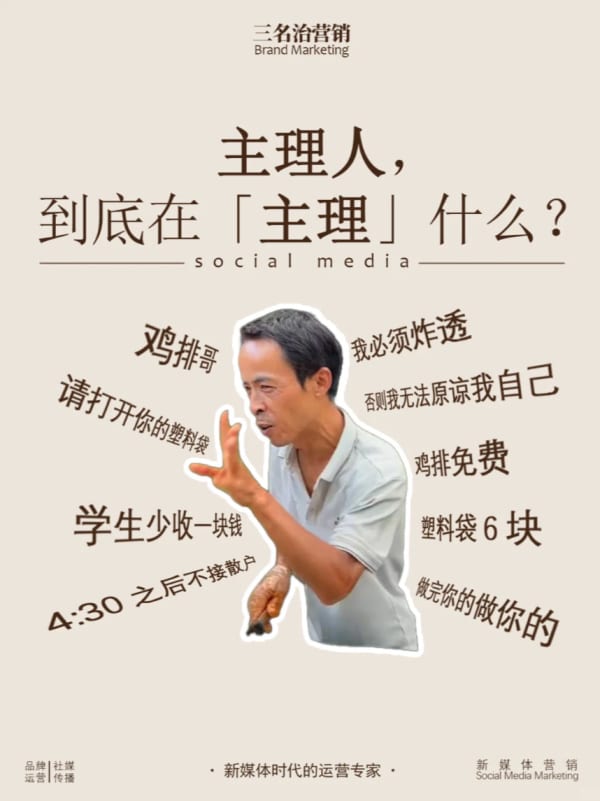

From Beijing to Zibo, every now and then, food stall vendors go viral — for their charm, their uniqueness, and most of all, their tasty food. The star of this moment is 48-year-old Li Junyong (李俊永), who runs a small fried chicken stall in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, with tight rules on who he serves, when, and how.

Li has suddenly become one of the most trending people on Chinese social media under the nickname “Chicken Chop Brother” (鸡排哥 jīpáigē).

Li initially gained popularity among customers for his frantic, multitasking energy — he doesn’t mess around when it comes to his chicken chop business, with superspeed and a clear order of serving customers (“I’ll first do you, then finish yours, then I’ll serve you 做完你的做你的”) and rules such as: no individual customers after 4:30 PM; students pay 1 yuan (about $0.15) less than regular passersby (after 12:00 PM, however, it costs 1 yuan more as punishment for being indecisive); and customers must open the plastic bag themselves before he puts the hot chicken cutlet inside.

The serious way he goes about dealing with his chicken chops almost makes you think he was making big business deals instead of selling to middle school students. In the end, it’s that attitude that gained him social media fame, as students started referring to him as “Head of Chicken Cutlet Operations” (free translation for 鸡排主理人 Jīpái gē Zhǔlǐrén).

Head of Chicken Chop Operations: “Please open your plastic bag”, “No individual customers after 4:30 PM”, etc.

In light of Li’s explosive popularity, his chicken chop stall now sees extremely long queues, and local authorities and city management have had to intervene in order to control the crowds and keep the location safe.

There are definite downsides to such sudden fame, and Li is not the first street vendor this has happened to.

In 2023, for example, Beijing’s ‘Auntie Goose Legs’ (鹅腿阿姨) went viral, and the food stall owner became so overwhelmed that she temporarily had to take a break from her food stall, emotionally sharing how she said she felt too much pressure because of how the situation was unfolding, and that she just wanted to sell her goose legs in peace (“只想平平安安做烧烤”).

Long lines for Auntie’s goose legs.

It seems that “Brother Chicken Chops”, in line with his reputation as the chicken chop CEO, is trying to turn his viral moment into a sustainable business. According to Sina News, Li has drawn in relatives to help him. He reportedly has taught them how to make and sell his tasty fried chicken chops, and now his Chicken Chop Family (“鸡排家族”) has grown to a total of nine stalls.

Over the past week, Li has also joined several social media platforms, including Xiaohongshu, to build a social following that will last after the hype calms down.

Meanwhile, Li is the meme of the moment. As many Chinese workers experience working stress before the National Day holiday, they’ve used his superspeed working style videos to express the pressure they feel to finish all their deadlines. See videos here.

— What Else Is Trending —

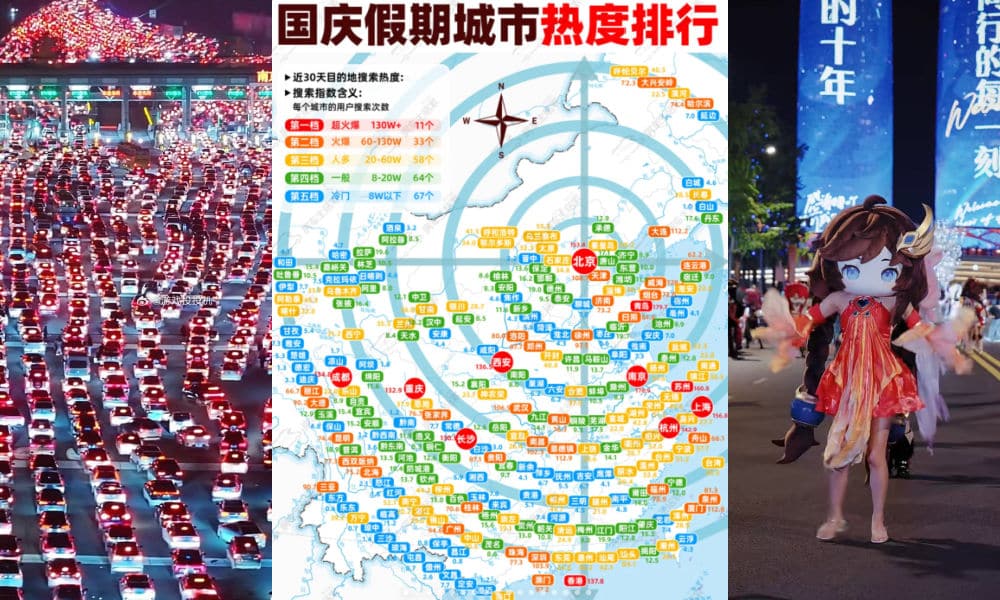

2. China’s 2025 Golden Week Travel Trends

China’s longest holiday of 2025 is coming up, combining National Day (国庆节) and Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节) into an eight-day Golden Week from October 1–8. If you’re traveling in China this week, good luck — the country’s transportation infrastructure is being pushed to its operational limits.

On September 30, the first “smart people” who opted to leave early to avoid traffic jams already found themselves stuck in them. China’s Ministry of Transport estimates a staggering 2.36 billion trips will be made during this period, with October 1 expected to see over 340 million travelers — surpassing the historical peak of 339 million recorded during Spring Festival earlier this year.

🔸 This week is going to see a lot of events. According to the Ministry of Culture & Tourism, more than 12,000 cultural activities will be held across China during the eight-day holiday period, including over 300 large-scale light shows.

🔸 Chinese local tourism offices are going all in on city marketing and are finding new strategies to make themselves more appealing to young travelers. Chengdu, for example, as Tencent’s gaming hub, is integrating the 10th anniversary of the super popular mobile game Honor of Kings (王者荣耀, Wángzhě Róngyào) into its cultural tourism strategy this year, organizing game-themed city walks, exhibitions, and more.

🔸 China’s travel platform Trip.com reported that interprovincial travel bookings have surged 45% year-on-year, with particularly strong interest in remote destinations like Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia. Searches for hotels in these regions jumped 60% compared to last year. This reflects a shift among middle-class Chinese tourists toward experiential travel and natural landscapes rather than crowded urban attractions.

🔸 The holidays are a time for relaxation, reunions, and eating mooncakes, but it’s also a stressful time for Chinese employers who must comply with labor regulations while managing workforce availability and overtime obligations. Under China’s Labor Law, employees working on statutory public holidays—October 1–3 and October 6 (the official Mid-Autumn Festival date)—must receive at least 300% of their normal daily wage. For adjusted rest days (October 4–5 and October 7–8), employers must provide either 200% overtime pay or compensatory time off. The State Council designated September 28 (Sunday) and October 11 (Saturday) as make-up workdays, but private companies have flexibility to adjust their own schedules.

3. China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

China is facing a serious donkey shortage. China’s donkey population is far below market demand, and the prices of donkey-related products continue to rise. The Donkey Branch of China’s Livestock Association (中国畜牧业协会驴业分会) addressed this issue in Chinese media earlier last week, telling China News Weekly (中国新闻周刊): “We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

4. “Ride-hailing for Relatives” 亲属打车 Qīnshǔ Dǎchē

Tencent has rolled out a new function via WeChat Mini Programs on September 26, aimed at helping seniors who struggle with app-based ride-hailing. Thanks to the new function, now live nationwide, users can order rides on behalf of older relatives directly in WeChat.

Adult children who want to help out their less tech-savvy (grand)parents or other senior relatives can now bind their account to their own, remotely pre-set pickup and drop-off locations, as well as payment methods, and track their journey for safety.

What makes this different from the possibility of just ordering a ride for someone else is that the seniors stay in control to some extent and can see their own journeys on their own phones. Children can configure settings on their side, while the interface for the elderly users is simplified. This allows seniors to ride independently, with a little help from their family.

The move is part of a broader effort in China to make it easier for seniors to stay involved in the digitalization of society.

The word to know is 亲属打车 qīnshǔ dǎchē, consisting of “亲属” qīnshǔ (relatives) and ride-hailing 打车 dǎchē.

5. What’s Trending at a Glance

- ✈️ The 27-year-old Sichuan creator “Tang Feiji” (唐飞机) died in a plane crash while livestreaming on Sept 27. The ultralight aircraft, piloted and purchased by Tang himself, went out of control and crashed before catching fire. Over 1,000 viewers were watching live, with the chat flooded by messages pleading for someone to rescue him. Local village officials confirmed his death. The tragedy is fueling debate over amateur aviation and extreme content creation.

- 🟢 Weibo has rolled out a visible “online status” feature on personal pages, showing when users are online, and not everyone is happy with it. The new feature is met with criticism from concerned users who don’t want others to see they’re online. It brings back memories of China’s legendary IM app QQ, which, like MSN, showed the online status of users.

- 🥿 A Chinese Marriott hotel location in Changzhou has come under scrutiny adn triggered hygiene concerns after guests found out that the in-room hotel slippers were being reused. The hotel has admitted to disinfected the disposable slippers and reusing them 2–3 times, without disclosing this to guests in advance.

- ⚖️ China’s cyberspace authorities issued stern warnings and announced penalties on various Chinese social platforms recently, including Xiaohongshu, Weibo, and Kuaishou, which are blamed for not keeping celebrity gossip and low-quality content in check and for influencing their hot search rankings. This is all about algorithm governance and the tightrope platforms walk in serving readers, attracting attention, and satisfying regulators.

- 👵 “Outsourced Children” services for Chinese seniors went trending recently. In Dalian, an initiative offering companionship and mediation services for seniors charges 500–2,500 yuan ($70–$350) per visit and has apparently been quite a success, underscoring strong market demand of eldercare-related services and new opportunities for Chinese students.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

“It’s in the Details” – The Xi-Trump ‘G2’ Meeting on Chinese Social Media

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

China’s “AFP Filter” Meme: How Netizens Turned a Western Media Lens into Online Patriotism

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral4 months ago

China Memes & Viral4 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Markus Havemann

January 13, 2021 at 9:35 am

“Through the internet’s black market, she found someone who would pay 20,000 yuan ($3085) for it.”

Who buys a birth certificate and why and for so much money?

After all, the birth certificate states the name of the child and the parents, so it should be easy to track down the buyer once he presents the birth certificate at any official place. And then the certificate can be retransfered to the girl it belongs to… So it is more or less worthless for the buyer?