Featured

Liberal Writer Li Jingrui Angers Chinese Feminists: “Weaklings and Warriors Are Not Defined by Gender”

Why do prominent mainland liberals speak out against Chinese feminism?

Published

8 years agoon

While Chinese feminist social media accounts are facing an online crackdown, a major discussion has erupted on Weibo after prominent liberal writer Li Jingrui voiced her negative stance on the feminist movement in the PRC today. The incident highlights the existing conflict between ‘mainland liberals’ and ‘mainland feminists.’

In the days following International Women’s Day, discussions on feminism in the PRC have been buzzing on Chinese social media.

A discussion that particularly received attention on Chinese social media this week is one that is taking place between mainland liberal thinkers and Chinese feminists on the issue of women’s power struggle in China.

The discussion was triggered when Li Jingrui (李静睿), a well-known female author and supporter of Chinese democratic activists, spoke out about China’s feminist movement. An online crackdown affecting various feminism-related social media accounts fuelled the debate.

FEMINIST VOICES SILENCED

“The account won’t be reactivated because it has posted ‘sensitive and illegal information.'”

On the eve of March 8, the renowned feminist Weibo account ‘Feminist Voices‘ (@女权之声), which had over 181,000 followers, was pulled offline after it had actively posted about Women’s Day during the day. The Feminist Voices’ Wechat account also disappeared the next day.

The ‘Feminist Voices’ Weibo and Wechat account were taken offline on and after March 8.

The Feminist Voices platform’s founding editor Lü Pin (吕频) spoke out on Twitter about the issue, saying that she was told by Sina Weibo’s customer service staff that the account would not be reactivated because it has posted “sensitive and illegal information.”

Lü Pin stated that preceding the account’s deletion, Feminist Voices had encouraged people on Weibo to announce their “anti-sexual harassment declaration” in response to the international #MeToo campaign.

Besides Feminist Voices, other accounts were also affected by the online crackdown around Women’s Day 2018. Amongst them was the ‘Feminist Forum’ (女权主义贴吧), which saw more than 19,000 Weibo posts erased from the internet by late February.

THE LI JINGRUI CONTROVERSY

“I would never use my female sex as an excuse for being weak. Weaklings and warriors are not defined by gender.”

While the heightened censorship caused outrage amongst many feminists on social media, a controversial post by the liberal writer and former legal journalist Li Jingrui (李静睿) popped up on Weibo. Li is well known for her involvement in social justice movements together with her husband Xiao Han (萧瀚), a prominent liberal scholar.

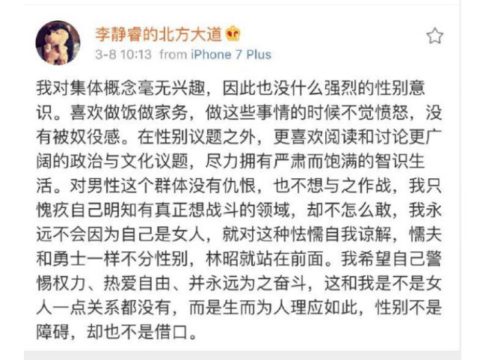

One of the Weibo posts by Li Jingrui triggering debate on Weibo.

In her post, Li addressed the Chinese feminist movement, writing:

“I have no interest in the concept of social collectives, and I have no strong sense of gender awareness. I like to cook and do housework. I don’t feel angered when I do these things, nor do I feel enslaved. Instead of focusing on gender issues, I prefer to study and discuss broader political and cultural issues, and spare no efforts to lead a serious and full intellectual life. I feel no hostility towards the male sex, and I do not feel like fighting them. I just feel guilty that I know there are certain things I really want to fight, but I do not have the guts to do so. I would never use my female gender as an excuse for being weak. Weaklings and warriors are not defined by gender. Lin Zhao* stood on the barricades. I hope I’ll [continue to be] be aware of power and treasure freedom – I’ll always fight for it. This has nothing to do with being a woman. It is a matter of humanity. Gender is not an obstacle, nor should it ever be an excuse.”

*Lin Zhao is a prominent Chinese dissident who was imprisoned and later executed during the Cultural Revolution for her criticism of Mao Zedong’s policies.

Shortly after Li Jingrui published her post, she received a lot of criticism from the online feminist community, of which many people previously supported Li for her contribution to civil rights activism in China, and for the fact that she and her husband address politic issues while facing strict censorship.

Some of the main problematic points of Li’s post as addressed by disgruntled feminists on Weibo are the following:

– That Li considers feminism as a social collective.

– That she reinforces the stereotype that feminists hate cooking and cleaning, and that they dislike men.

– That Li is unaware of her privilege to be able to choose if she wants to cook or clean, but that many women do not enjoy that same privilege.

– That she implies that her intellectual goals are more important and of a ‘higher standard’ than feminist goals are.

– That she hints that feminists are cowards who hide behind their gender.

– That she does not realize that feminists pursue the same human equality and freedom as she herself does.

Another issue that caused some consternation online is that Li’s husband Xiao Han also left a comment on Li’s post saying he agreed with her stance. Some commenters used this against Li, saying that she is “brainwashed” by her husband and relies on him to build her self-worth.

BROADER POLITICAL TOPICS

“My friends who are lawyers, public intellectuals, or Tibetan, have no platform to have their voices heard.”

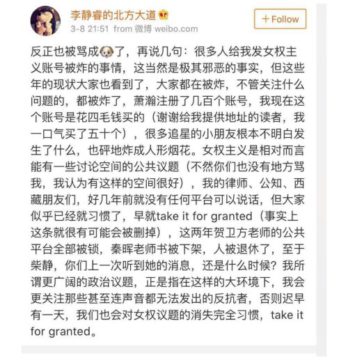

In response to the controversy her post evoked, Li Jingrui published another post on March 8 in which she reiterated her idea that there are more important matters in China’s public debate than feminist issues.

Li Jingrui

In this post, Li warns Chinese feminists that they still enjoy relative freedom of discussion compared to other activists in the PRC. Li mentions that lawyers, public intellectuals, and her “Tibetan friends” have since long been silenced and have no platform to speak from, something which seems to have already been “taken for granted.”

Li’s post, in which she writes: “My friends who are lawyers, public intellectuals, or Tibetan, have no platform to have their voices heard.”

Li explains that, instead of a focus on Chinese feminism, she would rather see attention shifted towards more “broad political topics” and to those whose voices are consistently silenced.

Her second post again received much criticism, with some commenters from feminist circles arguing that they were all facing “high censorship,” and that those topics undergoing more censorship were not necessarily more important than those facing less control.

Li’s main opponents come from a new generation of young Chinese feminists (both male and female) and online influentials such as Zhou Yun (周韵, @一音顷夏) or ‘@Linsantu.'[1]

But Li also received much support from like-minded commenters, including from influential accounts such as Luo Zhiqiu (@洛之秋) and Dagudu (@大咕咕咕鸡).

People speaking out for Li claimed that Chinese feminists are not “real feminists,” but “feminazis” (女权纳粹) or “countryside feminists” (中华田园女权: a term to describe women who label themselves as feminists but cherry pick the rights they think they should have).

In their defense of Li Jingrui, these commenters say that people such as Li and her husband are fighting the “real fight,” and are in touch with reality, supposedly unlike the Chinese feminists they attack.

MAINLAND LIBERALS VERSUS CHINESE FEMINISTS

“Li Jingrui just prioritizes human rights over women’s rights, what’s wrong with that?”

This is not the first time that China’s ‘mainland liberals’ clash with feminists. In “Mainland Liberalism and Feminism” (大陆自由派和女权主义 2016), Weibo blogger @bdf84 writes: “We may think that liberals pursue freedom and democracy, and oppose the oppression of totalitarianism. And since feminists oppose the oppression of women, the two are seemingly natural allies. But this is not true.” [2]

Although both mainland liberals and feminists care about people’s equality and oppression, their perspective on how oppression works and freedom can be attained is radically different. Whereas feminists mostly seek to explain (female) oppression through social and cultural (gender) constructions, mainland liberals are concerned with political systems, and generally, do not believe that culturally constructed power dimensions constitute oppression.

Now that the Li Jingrui has gained much attention on Chinese social media, there are also some people who do not understand the two sides of the discussion. “Since when do human rights oppose women’s rights?”, one netizen (@文盲摇曳有声) wonders. “Li Jingrui just prioritizes human rights over women’s rights, what’s wrong with that?”, others write.

But the two sides of the discussion show no signs of mutual understanding, as some feminist commenters respond with much indignation and are met with derision by their opponents.

Meanwhile, as fierce online debates continue, Li Jingrui has deleted the posts on her Weibo account related to the discussion. “My personal life has come under attack,” she says: “It’s useless. In the future, I will not participate in these kinds of discussions again.”

On Twitter, the editor of Feminist Voices is not involved in these discussions – she is mourning the account’s erasure during the recent crackdown. “The trace of us has been totally erased from social media in China,” Lü Pin writes: “We are still in shock.”

By Boyu Xiao & Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

[1] As described by Hariette Evans on Wagic.com, these new feminist communities are often transnational. @Linsantu, for example, is a Columbia University graduate, whereas Zhou Yun is a PhD candidate at Harvard University’s Sociology department.

[2] A 2013 article by Li Sipan (李思磐, alias of the political sociologist Li Jun) titled “Why don’t Chinese mainland liberals support feminism?” (“中国大陆自由主义者为何不支持女权主义?”) is also fully focused on this polarized discussion.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Boyu Xiao is an MPhil graduate in Asian Studies (Leiden University/Peking University) focused on modern China. She has a strong interest in feminist issues and specializes in the construction of memory in contemporary China.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform resurfaces in Africa, a new winter hotspot, why Chinese elites ‘run’ to Tokyo, and more.

Published

1 week agoon

November 21, 2025

🌊 Signals — Week 47 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China, Signals highlights slower trends and online currents behind the daily scroll. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Different from the China Trend Watch (check the latest one here if you missed it), this edition, part of the new Signals series, is about the slower side of China’s social media: the recurring themes and underlying shifts that signal broader trends beyond the quick daily headlines. Together with the deeper dives, the three combined aim to give you clear updates and a fuller overview of what’s happening in China’s online conversations & digital spaces.

For the coming two weeks, I’ll be traveling from Beijing to Chongqing and beyond (more on that soon) so please bear with me if my posting frequency dips a little. I’ll be sure to pick it up again soon and will do my best to keep you updated along the way. In the meantime, if you know of a must-try hotpot in Chongqing, please do let me know.

In this newsletter: Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform in Angola, a new winter hotspot, discussions on what happens to your Wechat after you die, why Chinese elites rùn to Tokyo, and more. Let’s dive in.

- 💰 The richest woman in China, according to the latest list by Hurun Research Institute, is the “queen of pharmaceuticals” Zhong Huijuan (钟慧娟) who has accumulated 141 billion yuan (over 19 billion USD). Women account for over 22% of Chinese billionaires (those with more than 5 billion RMB), underscoring China’s globally leading position in producing wealthy female entrepreneurs.

- 🧩 What happens to your WeChat after you die? A user who registered for NetEase Music with a newly reassigned phone number unexpectedly gained access to the late singer Coco Lee’s (李玟) account, as the number had originally belonged to her. The incident has reignited debate over how digital accounts should be handled after death, prompting platforms like NetEase and Tencent to reconsider policies on long-inactive accounts and take stronger measures to protect them.

- 📱 Although millions of viewers swoon over micro-dramas with fantasy storylines where rich, powerful men win over the “girl next door” through money and status, Chinese regulators are now stepping in to curb exaggerated plots featuring the so-called “dominant CEO” (霸道总裁) archetype, signaling stricter oversight for the booming short drama market.

- ☕ A popular Beijing coffee chain calling itself “People’s Cafe” (人民咖啡馆), with its style and logo evoking nationalist visual nostalgia, has changed its name after facing criticism for building its brand – including pricey coffee and merchandise – on Mao era and state-media political connotations. The cafe is now ‘Yachao People’s Cafe’ (要潮人民咖啡馆).

- 👀 Parents were recently shocked to see erotic ads appear on the Chinese nursery rhymes and children’s learning app BabyBus (宝宝巴士), which is meant for kids ages 0–8. BabyBus has since apologized, but the incident has sparked discussions about how to keep children safe from such content.

- 🧧The 2026 holiday schedule has continued to be a big topic of conversation as it includes a 9-day long Spring Festival break (from February 15 to February 23), making it the longest Lunar New Year holiday on record. The move not only gives people more time for family reunions, but also gives a huge boost to the domestic travel industry.

Hasan Piker’s Chinese Tour & The US–China Content Honeymoon

Livestreamer Hasan Piker during his visit to Tiananmen Square flag-rising ceremony.

It’s not time for the end-of-year overviews just yet – but I’ll already say that 2025 was the US–China ‘honeymoon’ year for content creation. It’s when China became “cool,” appealing, and eye-grabbing for young Western social media users, particularly Americans. The recent China trip of the prominent American online streamer Hasan Piker fits into that context.

This left-wing political commentator also known as ‘HasanAbi’ (3 million followers on Twitch, recently profiled by the New York Times) arrived in China for a two-week trip on November 11.

Piker screenshot from the interview with CGTN, published on CGTN.

His visit has been controversial on English-language social media, especially because Piker, known for his criticism of America (which he calls imperialist), has been overly praising China: calling himself “full Chinese,” waving the Chinese flag, joining state media outlet CGTN for an interview on China and the US, and gloating over a first-edition copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao (the Little Red Book). He portrays China as heavily misrepresented in the West and as a country the United States should learn from.

Hasan Piker did an interview with CGTN, posing with Li Jingjing 李菁菁.

During his livestreaming tour, Hasan, who is nicknamed “lemonbro” (柠檬哥) by Chinese netizens, also joined Chinese platforms Bilibili and Xiaohongshu.

But despite all the talk about Piker in the American online media sphere, online conversations, clicks, and views within China are underwhelming. As of now, he has around 24,000 followers on Bilibili, and he’s barely a topic of conversation on mainstream feeds.

Piker’s visit stands in stark contrast to that of American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins), who toured China in March. With lengthy livestreams from Beijing to Chongqing, his popularity exploded in China, where he came to be seen by many as a representative of cultural diplomacy.

IShowspeed in China, March 2025.

IShowSpeed’s success followed another peak moment in online US–China cultural exchange. In January 2025, waves of foreign TikTok users and popular creators migrated to the Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu amid the looming TikTok ban.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against Trump and US policies. In a playful act of political defiance, they downloaded Xiaohongshu to show they weren’t scared of government warnings about Chinese data collection. (For clarity: while TikTok is a made-in-China app, it is not accessible inside mainland China, where Douyin is the domestic version run by the same parent company).

The influx of foreigners — who were quickly nicknamed “TikTok refugees” — soon turned into a moment of cultural celebration. As American creators introduced themselves, Chinese users welcomed them warmly, eager to practice English and teach newcomers how to navigate the app. Discussions about language, culture, and societal differences flourished. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor. It was a rare moment of social media doing what we hope it can do: connect people, build bridges, and replace prejudice with curiosity.

Some of that same enthusiasm was also visible during IShowSpeed’s China tour. Despite the tour inevitably getting entangled with political and commercial interests, much of it was simply about an American boy swept up in the high energy of China’s vibrant cities and everything they offer.

Different from IShowSpeed, who is known for his meme-worthy online presence, Piker is primarily known for his radical political views. His China enthusiasm feels driven less by cultural curiosity and more by his critique of America.

Because of his stances — such as describing the US as a police state — it’s easy for Western critics to accuse him of hypocrisy in praising China, especially after a brief run-in with security police while livestreaming at Tiananmen Square.

Seen in broader context, Piker’s China trip reflects a shift in how China is used in American online discourse.

Before, it was Chinese ‘public intellectuals’ (公知) who praised the US as a ‘lighthouse country’ (灯塔国), a beacon of democracy, to indirectly critique China and promote a Western modernization model. Later, Chinese online influencers showcased their lives abroad to emphasize how much ‘brighter the moon’ was outside China.

In the post-Covid years, the current reversed: Western content creators, from TikTok influencers to political commentators, increasingly use China to make arguments that are fundamentally about America.

Between these cycles, authentic cultural curiosity gets pushed to the sidelines. The TikTok-refugee moment in early January may have been the closest we’ve come in years: a brief window where Chinese and American users met each other with curiosity, camaraderie, and creativity.

Hasan’s tour, in contrast, reflects a newer phase, one where China is increasingly used as a stage for Western political identity rather than a complex and diverse country to understand on its own terms. I think the honeymoon phase is over.

“Liu Sihan, Your School Uniform Ended Up in Angola”: China’s Second-Hand Clothing in Africa

A Chinese school uniform went viral after a Chinese social media user spotted it in Angola.

“Liu Sihan, your schooluniform is hot in Africa” (刘思涵你的校服在非洲火了) is a sentence that unexpectedly trended after a Chinese blogger named Xiao Le (小乐) shared a video of a schoolkid in Angola wearing a Chinese second-hand uniform from Qingdao Xushuilu Primary School, that had the nametag Liu Sihan on it.

The topic sparked discussions about what actually happens to clothing after it’s donated, and many people were surprised to learn how widely Chinese discarded clothing circulates in parts of Africa.

Liu Sihan’s mother, whose daughter is now a 9th grader in Qingdao, had previously donated the uniform to a community clothing donation box (社区旧衣回收箱) after Liu outgrew it. She intended it to help someone in need, never imagining it to travel all the way to Africa.

In light of this story, one netizen shared a video showing a local African market selling all kinds of Chinese school items, including backpacks, and people wearing clothing once belonging to workers for Chinese delivery platforms. “In Africa, you can see school uniforms from all parts of China, and even Meituan and Eleme outfits,” one blogger wrote.

When it comes to second-hand clothing trade, we know much more about Europe–Africa and US–Africa flows than about Chinese exports, and it seems there haven’t been many studies on this specific topic yet. Still, alongside China’s rapid economic transformations, the rise of fast fashion, and the fact that China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of textiles, the country now has an enormous abundance of second-hand clothing.

According to a 2023 study by Wu et al. (link), China still has a long way to go in sustainable clothing disposal. Around 40% of Chinese consumers either keep unwanted clothes at home or throw them away.

But there may be a shift underway. Donation options are expanding quickly, from government bins to brand programs, and from second-hand stores to online platforms that offer at-home pickup.

Chinese social media users posting images of school/work uniforms from China worn by Africans.

As awareness grows around the benefits of donating clothing (reducing waste, supporting sustainability, and the emotional satisfaction of giving), donation rates may rise significantly. The story of Liu Sihan’s uniform, which many found amusing, might even encourage more people to donate. And if that happens, scenes of African children (and adults) wearing Chinese-donated clothes may become much more common than they now are.

Laojunshan: New Hotspot in Cold Winter

Images from Xiaohongshu, 背包里的星子, 旅行定制师小漾

Go to Zibo for BBQ, go to Tianshui for malatang, go to Harbin for the Ice Festival, cycle to Kaifeng for soup dumplings, or head to Dunhuang to ride a camel — over recent years, a number of Chinese domestic destinations have turned into viral hotspots, boosted by online marketing initiatives and Xiaohongshu influencers.

This year, Laojunshan is among the places climbing the trending lists as a must-visit spot for its spectacular snow-covered landscapes that remind many of classical Chinese paintings. Laojunshan (老君山), a scenic mountain in Henan Province, is attracting more domestic tourists for winter excursions.

Xiaohongshu is filled with travel tips: how to get there from Luoyang station (by bus), and the best times of day to catch the snow in perfect light (7–9 AM or around 6–6:30 PM).

With Laojunshan, we see a familiar pattern: local tourism bureaus, state media, and influencers collectively driving new waves of visitors to the area, bringing crucial revenue to local industries during what would otherwise be slower winter months.

WeChat New Features & Hong Kong Police on Douyin

🟦 WeChat has been gradually rolling out a new feature that allows users to recall a batch of messages all at once, which saves you the frantic effort of deleting each message individually after realizing you sent them to the wrong group (or just regret a late-night rant). Many users are welcoming the update, along with another feature that lets you delete a contact without wiping the entire chat history. This is useful for anyone who wants to preserve evidence of what happened before cutting ties.

🟦The Hong Kong Police Force recently celebrated its two-year anniversary on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), having accumulated nearly 5 million followers during that time. To mark the occasion, they invited actor Simon Yam to record a commemorative video for their channel (@香港警察). The presence of the Hong Kong Police on the Chinese app — and the approachable, meme-friendly way they’ve chosen to engage with younger mainland audiences — is yet another signal of Hong Kong institutions’ strategic alignment with mainland China’s digital infrastructure, a shift that has been gradually taking place. The anniversary video proved popular on Douyin, attracting thousands of likes and comments.

Why Chinese Elite Rùn to Japan (by ChinaTalk)

Over the past week, Japan has been trending every single day on Chinese social media in light of escalating bilateral tensions after Japanese PM Takaichi made remarks about Taiwan that China views as a direct military threat. The diplomatic freeze is triggering all kinds of trends, from rising anti-Japanese sentiment online and a ban on Japanese seafood imports to Chinese authorities warning citizens not to travel to Japan.

You’d think Chinese people would want to be anywhere but Japan right now — but the reality is far more nuanced.

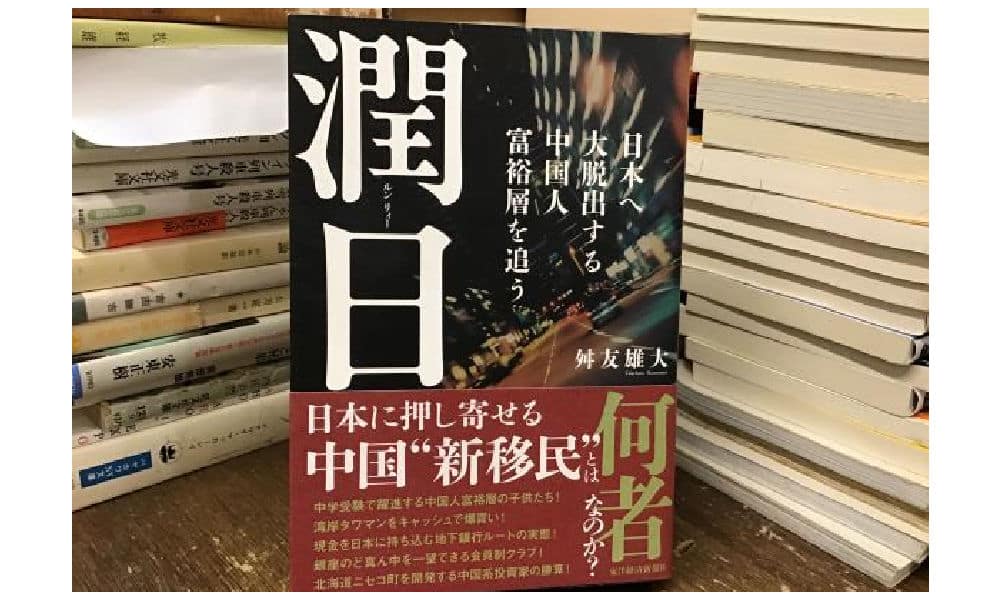

In a recent feature in ChinaTalk, Jordan Schneider interviewed Japanese journalist & researcher Takehiro Masutomo (舛友雄大) who has just published a book about Japan’s new Chinese diaspora, explaining what draws Chinese dissidents, intellectuals, billionaires, and middle-class families to Tokyo.

The book is titled Run Ri: 潤日 Following the Footsteps of Elite Chinese Escaping to Japan (only available in Japanese and Traditional Chinese for now). (The word Rùn 润/潤, by the way, is Chinese online slang and meme expresses the desire to escape the country.)

A very interesting read on how Chinese communities are settling in Japan, a place they see as freer than Hong Kong and safer than the U.S., and one they’re surprisingly optimistic about — even more so than the Japanese themselves.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China Signals. For fast-moving trends and deeper dives, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you just so happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

A small housekeeping note:

This Eye on Digital China newsletter is co-published for subscribers on both Substack and the main site. If you’re registered on both platforms, you’ll receive duplicate emails — so if that bothers you, please pick your preferred platform and unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Trend Watch

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

From quick scrolls to the discussions that matter, these are the topics trending in China this week.

Published

2 weeks agoon

November 16, 2025

🔥 China Trend Watch — Week 45-46 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to the Eye on Digital China newsletter. It has been an especially tumultuous week on Chinese social media: from the crisis triggered by Takaichi’s remarks to the Nexperia clash and the near-total blackout surrounding the Yunnan “wild child” case. Despite their differences, all of these stories share a common thread — mistrust, whether on the geopolitical stage or at home in institutions and state media.

Thank you for the kind reactions I received after the last newsletter, in which I took a bird’s-eye view of China’s evolving social media landscape and announced a soft goodbye to What’s on Weibo (if you haven’t read it yet, you can find it here).

I’m very grateful to everyone who has followed my journey with What’s on Weibo, and I’m excited to start this new chapter together.

Under the Eye on Digital China newsletter, you can expect updates in three categories: fast-moving trends, slower-burn signals, and longer thematic explorations — plus the occasional personal story, including from the road as I travel through China. (I’ll soon be covering roughly 3,000 miles across the country, so I’m sure I’ll run into plenty worth sharing.)

This is the China Trend Watch edition — a quick catch-up on real-time conversations. Let’s dive in.

- 🔺 A new 32-country survey by The Economist and GlobeScan found a sharp increase in the share of respondents who prefer China over the US as the world’s “leading power,” and younger people are driving much of this shift.

- 🛵 As Ele.me (China’s No.2 food-delivery platform) rebrands to “Taobao Flash Delivery” (淘宝闪购), competitor Meituan used it as the perfect marketing moment by bidding farewell to its long-time competitor with a virtual “memorial service,” complete with “farewell coupons.”

- 👀 Famous Chinese author and Nobel laureate Mo Yan (莫言) made his debut on the social media app Xiaohongshu this week, with a meme-ready video and posts. He’s been praised as a “meme king” for quickly adapting to the app’s community — gaining over 950,000 followers in just five days.

- 🏳️🌈 Two of China’s most popular gay apps, Blued and Finka (翻咔), have been removed from from Apple App Store in China as at the request of Chinese internet regulatory authorities. Last month, Blued – which has over 40 million registered users in China – temporarily suspended new user registrations after media reports accused the platform of facilitating encounters that led to HIV infections among minors.

- 🏆 A remarkable moment during the Golden Rooster Awards went viral after Ne Zha 2 won the award for Best Art Film — yet no one came to pick it up. Director Jiaozi (饺子) had already announced earlier in the year that he and his entire team would be too busy working on Ne Zha 3 to attend any events — and he, very clearly, is a man of his word.

- 🔻 Chinese-Canadian celebrity Kris Wu (吴亦凡), convicted in 2022 for rape and sentenced to 13 years in prison, keeps reappearing in online discussions — but only through rumors. This week, speculation about his possible death in prison spread across social media yet again (“What, did he die again?” some joked). Local authorities have denied the rumors.

1. Sino-Japanese Tensions Escalate After Takaichi’s Taiwan Remarks

Political cartoon circulating on Chinese social media, made by Jun Zhengping (钧正平), official social media name/persona used by the People’s Liberation Army.

With the recent appointment of conservative politician Sanae Takaichi (高市早苗) as the new prime minister of Japan, seen as the ideological successor to Shinzo Abe, many expected renewed Sino-Japanese tensions due to her stances on various sensitive bilateral issues, from wartime history to Taiwan. But perhaps few expected relations to escalate so quickly and so intensely.

This week, Japan and Takaichi have been top trending topics after she made provocative remarks during a hearing in the Diet about potential military intervention in Taiwan-related matters, suggesting Japan’s Self-Defense Forces could exercise the right of collective self-defense if such a situation were recognized as “survival-threatening.” She is also pushing defense-related policy changes, including exploring revisions to Japan’s “three non-nuclear principles.”

The remarks have set off a chain of events — and online trends — marking what may be the worst flare-up in ties since 2012, when major anti-Japanese protests erupted in China following Japan’s purchase of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Chinese officials are sharpening their tone, issuing angry and escalatory diplomatic statements via X, domestic social media, and Foreign Ministry press briefings.

The recent escalations have also led to official warnings about safety risks for Chinese nationals in Japan. On Sunday, China’s Ministry of Education advised Chinese citizens to exercise caution when planning study-abroad arrangements in Japan.

Beyond nationalist discourse and general anti-Japanese sentiment on Chinese social media — and users vowing not to travel or study there — many discussions are also focusing on geopolitics and history rather than consumer boycotts. Well-known nationalist knowledge blogger Pingyuan Gongzi Zhao Sheng (@平原公子赵胜) posted a lengthy post on Weibo (crossposted to Xiaohongshu) suggesting that Japan is filled with ‘deadly energy’ (死气 sǐqì) – acting irrationally and aggressively because it is in complete decline — socially, economically, technologically, and militarily — but unable to accept it. He argues that a strong and stable country would never gamble its future like this, and that only a “zombie-like” nation in denial would provoke China unnecessarily. A related hashtag about Japan’s gloomy status-quo (#日本死气#) has also been used by other commentators across social media.

2. New Updates in Yunnan’s “Wild Child” Case Raise More Questions

Last month, I wrote about a distressing case involving a 3-year-old boy from Nanjian County (南涧县) in Yunnan who was seen walking on all fours, behaving dog-like with possible spinal deformities, naked and apparently neglected by his parents. Several netizens recorded the scene, and videos quickly spread online in mid October, with thousands referring to the boy as the “wild child” (野孩子 or “naked child” 赤裸小孩) of Yunnan and demanding that authorities intervene and hold the parents accountable.

What followed was a wave of confusing — and sometimes contradictory — media reports. Some outlets initially claimed the boy’s parents were impoverished and struggling, while others reported they were well-educated and financially stable, framing their dubious parenting approach as a deliberate and philosophical “lifestyle choice.”

The parents, who live a camper-van lifestyle, turned out to both hold university degrees (the mother even holds a post-graduate degree). They claimed they practice “natural education” (自然教育法) and said their son disliked wearing clothes because of eczema. Some reports said they refused to cooperate with local authorities; others said they agreed to stop letting their child crawl around naked. Neither the 3-year-old nor his younger brother had ever been registered for a household hukou (registered permanent residence), raising further concern.

Online, speculation intensified. Many netizens feared the child was being deliberately mistreated for profit, suggesting a dark-web content industry behind the scenes.

This week, local authorities and state media posted a new update, releasing a video of the boy — referred to as Pingping (平平, an alias) — walking and playing normally. According to officials, the parents are now receiving support and guidance in raising their children, and both boys are being issued official household registrations by local authorities. The investigation, they said, found no evidence that the parents were involved in “illegal online profit-making.”

But many netizens are anything but convinced. They argue the child shown in the video isn’t the same boy — his face is blurred, and his voice appears overdubbed. Posts questioning the official narrative are being censored. And although authorities say the case is now closed, with the family under ongoing guidance, many people online feel the story is anything but over, and that the real truth still hasn’t surfaced.

Some of the doubts about the veracity of the story and videos are being expressed in more subtle ways to avoid censorship. One Weibo commenter simply wrote that “mild spinal deformities in a 3-year-old may improve within 3–6 months through corrective treatment (…) while recovery from severe deformities may take 1–2 years or even longer” — subtly suggesting that it would be impossible for the boy to be walking and playing normally now if he had shown signs of spinal deformity just weeks earlier. On Douyin, users also questioned what happened to the supposedly severe eczema that had allegedly prevented the boy from wearing clothes. A Zhihu writer expressed frustration: “The official report is extremely fake, but there’s no way to talk about it.” Another commenter echoed the sentiment: “People today aren’t stupid. Even if you forbid them to speak, do you think they won’t know something is wrong?” For many, the case is troubling not only because of the child’s situation, but because the official handling of it has reinforced a growing sense that the public is being managed rather than informed.

3. Nexperia and Dutch ‘Pirate Gene’ Discussions

It wasn’t just bilateral relations with Japan that took a hit this week — tensions between China and the Netherlands have also deepened due to the ongoing dispute surrounding Dutch intervention in the chipmaker Nexperia. This is an issue I wrote about last month. After the incident made international headlines, China responded by blocking the export of Nexperia chips from its factory in China, putting major European automakers at risk of running short on critical components for vehicle electronics.

In brief: Nexperia (安世半导体), a Dutch semiconductor company based in Nijmegen and wholly owned by the Chinese conglomerate Wingtech (闻泰科技) since 2019, became the center of a major diplomatic clash after the Dutch government reportedly ordered a one-year freeze on strategic and governance changes within the company on September 30. Citing national security concerns and a desire to secure domestic chip production, the Dutch move came amid reports that Nexperia CEO Zhang Xuezheng was relocating production facilities and sensitive technology from Europe to China.

While tensions had previously seemed to ease, the conflict escalated again this week. The Dutch public broadcasting organization reported on a widening rift as Nexperia China accused the Dutch branch of disrupting production by refusing to send chip components to the Dongguan factory. Meanwhile, Nexperia Netherlands claimed the Chinese side had been urging customers to reroute payments away from the Netherlands and into Chinese bank accounts. A Dutch delegation is expected to travel to Beijing next week to discuss the situation and attempt to break the deadlock.

On Chinese social media, many users view the Dutch actions as an unfair use of a Cold-War-era law to target a modern, legally operating multinational company. The move is widely seen as another example of Western countries shifting rules to maintain technological dominance when faced with strong competition from Chinese firms. As a result, what began as a company-specific dispute has grown into a broader geopolitical struggle over global chip control and economic sovereignty.

Modern Opium [当代鸦片] (dāngdài yāpiàn)

Over the past year, the term “modern opium” has become more common on Chinese social media— used as a popular term to promote food or other products. It’s perhaps not unlike the famous “finger-licking good” slogan in the West, but applied far more broadly, also to refer to “addictive” online accounts, collector toys, or restaurants. In fact, it has become so commonplace that you can now find “modern-opium food recommendation” suggestions on platforms when searching for good places to eat in major Chinese cities.

Recently, the term began trending as a controversial expression after Chinese media focused on an official online complaint arguing that it “turns national trauma into entertainment” (将民族伤痛娱乐化) and trivializes a painful chapter of Chinese history, drawing a direct connection to the Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860).

The complaint has put the term at the center of public attention — but how controversial is it, really? While Chinese media are eager to highlight how inappropriate the phrase is, given China’s collective memory of the “century of humiliation,” many Xiaohongshu users nevertheless seem to think it’s perfectly acceptable to describe their newfound addiction to a milky drink, a sweet dessert, or the perfect hotpot. (I can relate to the latter.)

During this year’s Single’s Day Shopping Festival (11.11), “Europe” was a popular item on shopping lists, not for its fashion or chocolate, but for anti-theft tools. Using “Europe is not safe” slogans and real footage of pickpockets in action, hundreds of Taobao sellers promoted handy anti-theft accessories for Chinese tourists traveling abroad, some even labeled for specific countries, from Spain to Germany.

This year’s shopping festival reportedly generated 1.695 trillion RMB ($238B) across platforms — still up 14.2% year-on-year, but with far slower growth than in previous years (2024: 26.6% growth). Jing Daily noted a noticeably more negative social media vibe surrounding the festival, with young consumers on Xiaohongshu growing more skeptical and questioning its purpose. Gen Z users are prioritizing timeless purchases over trend cycles and embracing more practical spending (like gadgets to avoid getting robbed in Europe).

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China China Trend Watch. For slower-moving trends and deeper structural analysis, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or

email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral5 months ago

China Memes & Viral5 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

docphd

March 15, 2018 at 5:39 am

Both sides are full of ideologues intolerant of differences and uninterested in human beings other than in an abstract sense. How is that different from the mentality of Red Guards? U know what? AT least the communists know how to run a huge mess of a country that is China. These anti-chicom ‘freedom fighters’ can’t organise a piss up in a brewery.