China Health & Science

That Time of The Month? Chinese State Media Explain How to Use Sanitary Towels

Shortly after a large-scale fake sanitary pad scandal has been exposed in China, state-run newspaper People’s Daily explains women how to correctly use menstrual pads and how to differentiate real from fake ones.

Published

9 years agoon

Shortly after a large-scale fake sanitary pad scandal has been exposed in China, state-run newspaper People’s Daily teaches women how to correctly use menstrual pads and how to differentiate real from fake ones. Many netizens do not appreciate the ‘non-counterfeit sanitary towel’ crash course.

A few days after a ‘fake sanitary pad’ scandal sparked health concerns in China, People’s Daily – the most influential state-run newspaper in China – explains to women on Weibo how to correctly use sanitary pads, and how to tell if they are real or fake.

“Girls, are you really using sanitary pads correctly?”

“Girls, after all these years, are you really using sanitary pads correctly?”, the People’s Daily posted on Sina Weibo on October 29, as spotted by What’s on Weibo.

Nanchang police recently discovered counterfeit sanitary pads that were sold under Chinese well-known brand names such as ‘ABC’ or ‘Sophie (苏菲). The fake sanitary pads were produced in a factory without the proper sterilization, which could potentially cause health problems for women using them.

“How can you tell if a sanitary pad is counterfeit?”, People’s Daily posted: “And what are the common misconceptions about the use of sanitary pads? How can women choose the right type of sanitary towel?”

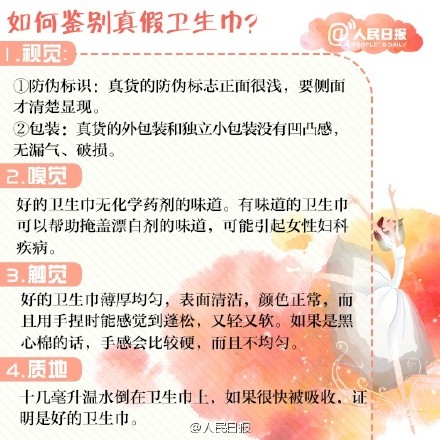

People’s Daily posted several infographics explaining how to differentiate a fake pad from a real one, and how to properly use sanitary pads.

“How to differentiate real from fake menstrual pads?”

Under the header of “how to differentiate real from fake menstrual pads?” (“如何鉴别真假卫生巾”), the Chinese newspaper warns women to pay attention to the look, smell, shape, and quality of sanitary pads.

Non-counterfeit sanitary towels are properly packed and have no visible damages. There should be no chemical smell to the pads, and their thickness should be even. They should also be able to quickly absorb 10mm or more of water – which is a quick test to see if a sanitary pad is real, according to the Weibo post.

Besides offering a crash course in differentiating fake from real menstrual pads, People’s Daily advises women to change their sanitary pads every 2-3 hours – no matter whether their menstruation is heavy or light – to avoid reproduction of bacteria.

The infographic also warns women not to use old sanitary towels, even if they have never been opened, because keeping them for too long after the production date might allegedly affect its quality and hygienic standard.

The state media outlet advises women to frequently change sanitary napkins that have high absorption capacity and not to use sanitary pads if it is not necessary to do so.

Lastly, People’s Daily says that women should be cautious about buying menstrual pads that are sold at a discount price and to buy reputable brands instead of new or unknown ones.

“It should not be up to women to distinguish real sanitary pads from counterfeit ones.”

The People’s Daily Weibo post soon triggered thousands of reactions from netizens. Many are angry that the newspaper advises women on how to look out for fake menstrual pads.

“I feel that it should not be up to women to distinguish real sanitary pads from counterfeit ones; it is up to the concerning departments to control and supervise [the sale of menstrual pads],” one netizen comments: “The people involved in illegal sales should be heavily punished!”

“This is too funny!”, another Weibo user says: “Now all women have to master how to differentiate between fake and real sanitary napkins.”

[rp4wp]

“We are already in pain, and now we also have to think about if what we buy is real or not,” another female netizen complains.

“You don’t realize how poor many people are, and how expensive menstrual pads are. And now they can not only be fake, but you also tell us to change them every 2-3 hours, well that’s at least 7 pads a day (..) – the costs are just too high.”

“When you live in China, you have to able to tell if meat is fake, if alcohol is fake, if hotpot ingredients are fake, if gasoline is fake (..), and now even women ‘whose aunt is visiting’ are encountering fake products!”

“Now my menstruation just scares me even more.”

By now, the People’s Daily post has been shared thousands of times on Chinese social media, with the hashtag “Are you really using sanitary towels correctly? (#你真的用对卫生巾了吗#) being one of the top trending topics on Weibo’s ‘hot search’ list.

The issue has also been covered by other media outlets, from newspapers to (local) TV channels. Although People’s Daily is serious in its intention to teach women how to correctly use non-counterfeit menstrual pads, most netizens are either angered or humored by this ‘crash course.’

“As women, we already have to endure so much and now this too,” one person writes.

For other Weibo users, all this talk about ‘that time of the month’ just is another reason to dread it. “Now my menstruation just scares me even more,” one netizen writes.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow on Twitter or Like on Facebook

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

[showad block=1]

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chapter Dive

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

Han Futao’s explosive report on fake patients and systemic abuse has triggered a heated online debate over hospital malpractices, the fragility of the welfare system, and the vital role of investigative reporting.

Published

11 hours agoon

February 15, 2026By

Ruixin Zhang

In early February, as China settled into the quiet anticipation of the Chinese New Year, one of the country’s leading investigative journalists, Han Futao (韩福涛), dropped a bombshell report that sent shockwaves of anger across the country.

Han Futao is known for breaking massive scandals. In 2024, he exposed how tank trucks that delivered chemical products also transported cooking oil, without being cleaned. That food safety scandal sparked waves of outrage and prompted a high-level official investigation, leading to criminal charges for those involved.

In his latest explosive report, published by Beijing News (新京报), Han has turned his lens to malpractice in China’s hospital sector. His investigation led him to Xiangyang, in Hubei province, a city with more than twenty psychiatric hospitals, cropping up on every corner “like beef noodle shops” over recent years.

Recruiting Patients

Han found that multiple private psychiatric hospitals lure people in under the guise of free care, promising treatment for little or no cost, along with medication and daily expenses. Some even dispatched staff to rural villages to recruit “patients.”

Troubled by the unusual marketing procedures of these psychiatric hospitals, Han went undercover at several facilities as a caregiver, and sometimes posing as a patient’s family member, only to expose a disturbing reality.

Except for a handful of genuine patients, these hospitals were filled with healthy people who actually received no treatment. Many were elderly citizens swayed by the promise of “free care,” checking in with the hope of finding a free retirement home.

When Han, posing as a patient’s family member, spoke to a hospital manager at Xiangyang Yangyiguang Psychiatric Hospital (襄阳阳一光精神病医院), the director enthusiastically pitched their “free hospitalization” by saying medical fees were completely waived and promising the potential patient a great stay: “Lots of patients stay here for years and don’t even go home for Chinese New Year!”

Meanwhile, the hospitals’ own staff, including caregivers, nurses, and security guards, were also officially registered as patients, complete with admission and hospitalization procedures.

The motive was simple: insurance fraud (骗保 piànbǎo). In China, even after state medical insurance covers part of psychiatric care costs, patients are typically still responsible for a co-pay. These hospitals, both in Xiangyang and in the city of Yichang, exploited the financial vulnerability of those unwilling or unable to pay, using the lure of free accommodation to attract the misinformed. Once admitted, the hospitals used their identities to fabricate medical records and bill the state for non-existent treatments.

According to internal billing records, medication accounted for only a small fraction of patients’ costs. The bulk of the charges came from psychotherapy and behavioral correction therapy, which often leave little material trace and, in these cases, were never actually provided. Many of these hospitals even lacked basic medical equipment and qualified personnel.

Staff were essentially manufacturing invoices, generating around 4,000 yuan (US$580) in fraudulent charges per patient each month, with most funds diverted from the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA).

With each patient yielding thousands of yuan, profitability became a numbers game: the more bodies in beds, the higher the revenue. This perverse incentive gave rise to a specialized workforce of marketers who recruited ordinary people from rural areas, developing sales pitches and establishing referral-based kickback chains, offering bonuses of 400 ($58) to 1,000 yuan ($145) for every new “patient” successfully brought in.

To stay under the radar, hospitals periodically discharged patients on paper to avoid scrutiny from insurance auditors, only to readmit them immediately, or never actually let them leave at all. One story involved a patient who was discharged seven times, each time being readmitted on the same day he was “discharged.”

Day after day, the national medical insurance fund, built on the collective contributions and trust of the entire population, was drained through these calculated deceptions.

From Patients to Prisoners

Han uncovered more. Even more harrowing than the scale of the medical insurance fraud was the condition of those trapped inside. To maximize profit margins, these hospitals slashed costs to the bone. Living conditions were terrible: wards overcrowded, beds crammed side-by-side, and daily activities and food substandard at best.

The hospitals treated their patients more like profit-generating assets than human beings. Patients were subjected to a strict regime: they were forced to follow rigid schedules, restricted to designated zones, and faced physical violence if they did not comply.

During Han’s undercover research, he witnessed the horrific sight of patients being tied to a bed for not following orders, with some patients allegedly being restrained for up to three days and three nights.

Photo by Han Futao, in Beijing News, showing a hall filled with beds at the Yichang Yiling Kangning Psychiatric Hospital, where more than 160 people were housed in just one ward. The lower photo, also by Han Futao, shows elderly “patients” kept in their wheelchairs all day at Xiangyang Hong’an Psychiatric Hospital.

Some patients, despite technically being the ones receiving care, were forced to perform manual labor for the staff. They scrubbed pots, cleaned wards, mopped latrines, and moved supplies. Others even had to take on nursing tasks for fellow patients, such as feeding, bathing, and changing clothes, all in exchange for a few cents to buy a cigarette. Their personal freedom and quality of life were virtually non-existent.

Escape was also difficult. The hospitals had no intention of releasing their cash cows. Rarely was a patient discharged on the scheduled date. To ensure long-term residency, many hospitals confiscated patients’ phones and cut off contact with their families.

Some individuals spent nearly ten years in these prison-like conditions; some even died there. Meanwhile, those truly suffering from mental illness received no real treatment, often seeing their condition worsen or developing deep-seated trauma toward psychiatric care.

Fragile Public Trust in Welfare-Related Institutions

In China, there is a common belief that if you spot one cockroach in the room, there are already a hundred more hiding. As the story has gone viral over the past two weeks, netizens pointed out that Xiangyang and Yichang were likely not the only cities using such predatory tactics to cannibalize the national treasury. Han’s investigation struck a deeper nerve, and public anxiety over the security of social insurance once again bubbled to the surface.

China’s national health insurance is a cornerstone of the broader social insurance system and a vital part of life for nearly every citizen. It is generally divided into two categories: Employee Medical Insurance and Resident Medical Insurance. Employers are legally, at least in theory, required to contribute to the employee scheme, typically 6% to 9% of a worker’s salary. Non-employees, such as farmers, students, and freelancers, usually pay for Resident Insurance out of pocket, currently costing around 400 yuan ($58) annually. Under the employee scheme, inpatient reimbursement rates are roughly 80% to 85%; after approximately 25 years of contributions, members enjoy lifelong coverage without further payments. The Resident Insurance, however, offers significantly lower protection.

This system was designed as a fundamental safety net to alleviate the fear of falling into poverty due to illness or being left destitute in old age. For young Chinese job seekers, whether a company pays into social security used to be a non-negotiable criterion. However, as scandals shaking the foundation of this system have become more frequent, the mindset of the youth is shifting: Is it even worth paying into anymore?

Recent years have seen a steady stream of corruption scandals involving the embezzlement of social security funds.

Despite the authorities’ firm stance and high-profile punishments, 2025 was still marked by reports of officials — including the insurance bureau’s finance head — misappropriating funds to play the stock market. A June 2025 report even alleged that 40.6 billion yuan (US$5.8 billion) in national pension funds had been misappropriated or embezzled by local governments.

In one surreal case from Shanxi, a CDC employee’s records were doctored 14 times to create an absurd history of “starting work at age 1 and retiring at 22,” allowing them to pocket 690,000 yuan ($100,000) in pension while still drawing a salary at a new job.

These stories exposing large-scale abuse of the medical insurance system, combined with the extension of the minimum contribution period for retirement from 15 to 20 years amid a slowing job market and a gradually rising retirement age, are leading netizens to question the necessity of paying into the system. This is reflected in comments such as:

-“First it was 20 years, then 25, then 30. They move the goalposts whenever they want, but the benefits never improve.”

-“I won’t buy anything beyond the bare minimum resident insurance; who knows if there will even be a payout in the future?”

-“With a deficit this large, whether we’ll ever see that money is a huge question mark.”

-“I’m not even sure I’ll live to see 65 anyway.”

Echoes of the Cuckoo’s Nest

In response to Han’s latest exposure, local authorities immediately launched investigations, and state-run media outlets issued sharp criticism. By now, fourteen hospital executives have been criminally detained on suspicion of fraud.

Although the official report, published on the night of February 13, acknowledged that there was widespread medical fraud, with patients remaining hospitalized after recovery or empty beds being registered without any patients there, it said no evidence was found that people without mental disorders were admitted, which was one major finding of Han’s undercover operation.

This led to new questions, because how could fraud, abuse, fake discharges, and official corruption be acknowledged while denying the central allegation: that healthy people were being locked up? And how could people prove they were not mentally ill, while being a patient inside a psychiatric hospital?

Political & social commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) wrote on Weibo that, while he applauded Han and his team for exposing the mismanagement at psychiatric hospitals in Hubei, he also saw the report’s conclusions about the patients as a reminder that journalists should exercise caution when making accusations. Some sarcastic commenters suggested that perhaps Han had not sacrificed enough and should have admitted himself as a patient instead.

And so, in a way, the debate has now slowly also shifted – from the initial shock over Han’s report, to the anger and distrust surrounding state institutions and social security abuse, to the role of investigative journalism in China today. “He’s a hero,” some commenters said about Han.

In the end, the entire story is so absurd that some commentators have drawn parallels to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (飞越疯人院), where Randle P. McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) fakes insanity to serve his sentence in a mental hospital instead of a prison work farm, only to find out that the endless chain of control and abuse at the psych ward is much more brutal than a prison cell.

The question inescapably becomes who the sane ones actually are.

Meanwhile, the scandal shows that public anxiety about the future and distrust of state institutions tend to rise quickly and deepen slowly with each new controversy. As trust in the national welfare system appears fragile, one sentiment persists: that there is far more to uncover, and that there are far too few Han Futaos to do it.

By Ruixin Zhang

With additional reporting by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Animals

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

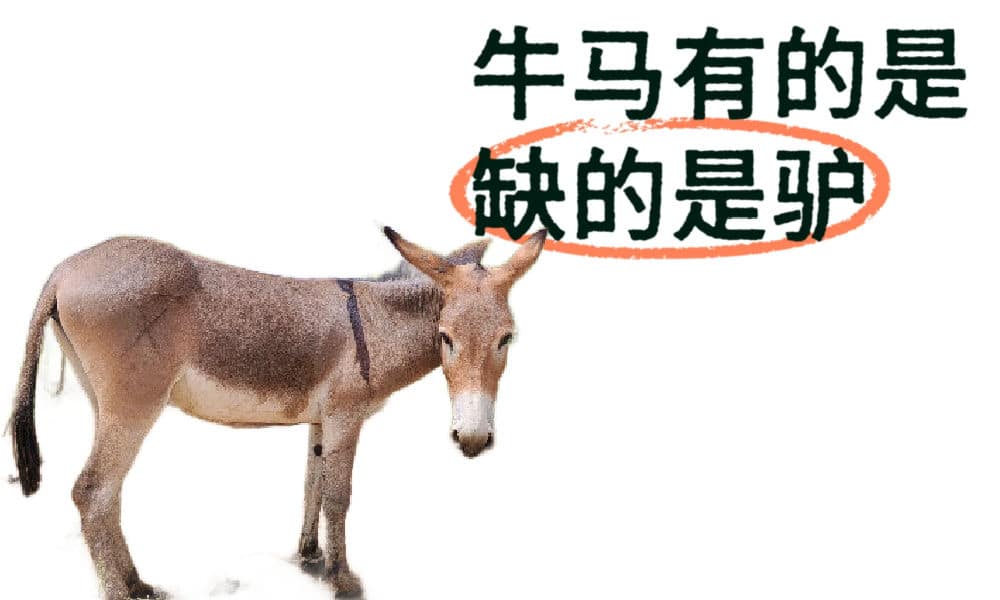

“We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

Published

4 months agoon

October 5, 2025

China is facing a serious donkey shortage. China’s donkey population is far below market demand, and the prices of donkey-related products continue to rise.

Recently, this issue went trending on Weibo under hashtags such as “China Currently Faces a Donkey Crisis” (#我国正面临缺驴危机#).

The Donkey Branch of China’s Livestock Association (中国畜牧业协会驴业分会) addressed this issue in Chinese media earlier last week, telling China News Weekly (中国新闻周刊): “We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

China’s donkey population has plummeted by nearly 90% over the past decades, from 11.2 million in 1990 to just 1.46 million in 2023.

The massive drop is related to the modernization of China’s agricultural industry, in which the traditional role of donkeys as farming helpers — “tractors” — has diminished. As agricultural machines took over, donkeys lost their role in Chinese villages and were “laid off.”

Donkeys also reproduce slowly, and breeding them is less profitable than pigs or sheep, partly due to their small body size.

Since 2008, Africa has surpassed Asia as the world’s largest donkey-producing region. Over the years, China has increasingly relied on imports to meet its demand for donkey products, with only about 20–30% of the donkey meat on the market coming from domestic sources.

China’s demand for donkeys mostly consists of meat and hides. As for the meat — donkey meat is both popular and culturally relevant in China, especially in northern provinces, where you’ll find many donkey meat dishes, from burgers to soups to donkey meat hotpot (驴肉火锅).

However, the main driver of donkey demand is the need for hides used to produce Ejiao (阿胶) — a traditional Chinese medicine made by stewing and concentrating donkey skin. Demand for Ejiao has surged in recent years, fueling a booming industry.

China’s dwindling donkey population has contributed to widespread overhunting and illegal killings across Africa. In response, the African Union imposed a 15-year ban on donkey skin exports in February 2023 to protect the continent’s remaining donkey population.

As a result of China’s ongoing “donkey crisis,” you’ll see increased prices for donkey hides and Ejiao products, and oh, those “donkey meat burgers” you order in China might actually be horse meat nowadays. Many vendors have switched — some secretly so (although that is officially illegal).

Efforts are underway to reverse the trend, including breeding incentives in Gansu and large-scale farms in Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang.

China is also cooperating with Pakistan, one of the world’s top donkey-producing nations, and will invest $37 million in donkey breeding.

However, experts say the shortage is unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

The quote that was featured by China News Weekly — “We have cows and horses, but no donkeys” (“牛马有的是,就缺驴”) — has sparked viral discussion online, not just because of the actual crisis but also due to some wordplay in Chinese, with “cows and horses” (“牛马”) often referring to hardworking, obedient workers, while “donkey” (“驴”) is used to describe more stubborn and less willing-to-comply individuals.

Not only is this quote making the shortage a metaphor for modern workplace dynamics in China, it also reflects on the state media editor who dared to feature this as the main header for the article. One Weibo user wrote: “It’s easy to be a cow or a horse. But being a donkey takes courage.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West