China Arts & Entertainment

Behind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

What’s behind the Dao Lang hit song that has everyone talking these days?

Published

2 years agoon

By

Zilan Qian

“Who is being mocked and cursed in this song?” This question has ignited a wildfire of speculation across the Chinese internet, as a recently released folk song by a relatively low-profile singer has amassed a staggering 8 billion plays, surpassing the success of previous hit songs.

A newly released Chinese song, composed and sung by a 52-year-old singer who was primarily active in the 2000s, has achieved an astounding milestone of 8 billion streams in less than two weeks since its release.

The song, titled “Luosha Haishi” (罗刹海市; “Raksha Sea Market” or “Luocha Kingdom”), has been widely acclaimed on various social media platforms, with many claiming that it has surpassed the Guinness World Record for the most streamed track worldwide, a record previously held by “Despacito” in 2017 with 5.5 billion plays. The official Weibo account of Guinness World Records recently stated that they haven’t received any application for a new record yet, and thus, no record has been officially confirmed broken at this time.

However, even 8 billion plays alone are enough to marvel at. The sudden surge in popularity of a song created by a low-profile singer, who has not participated in any major shows or held performances for the last few decades, has raised numerous questions: Who is the singer? What is in the song? And why has it become viral in China? We’ll answer some of these questions for you here.

Question 1: Who is Dao Lang?

Dao Lang (刀郎), whose real name is Luo Lin (罗林), embarked on his musical journey at a young age. Born in 1971, he made the decision to leave school at the age of 17 and fully immerse himself in learning keyboard instruments at a music hall in Neijiang. Over the next four years, he ventured to different locations such as Chengdu, Chongqing, Tibet, and Xi’an, where he gained experience and honed his musical skills. Throughout the 1990s, he actively participated in various music projects and bands, shaping his career in the music industry.

In 2004, Dao Lang’s album The First Snow of 2022 (2002年的第一场雪) was unexpectedly well-received, winning him nationwide popularity. After enjoying success with previous albums, Dao Lang diversified his musical endeavors, collaborating with other artists and exploring different genres, such as folk and ethnic music. Between 2010 and 2012, he participated in various performances and events, including appearing at Hong Kong singer Alan Tam’s concert and the Television Arts Evening Celebration for the 90th Anniversary of the Communist Party of China’s founding.

Dao Lang (Weibo).

Subsequently, Dao Lang appeared to withdraw from social media, only resurfacing with two albums in 2020 and 2021, which were released with minimal promotion. However, it is his latest album, titled There Are Few Folk Songs (山歌寥哉) that has brought him back into the public eye, primarily due to the “Luosha Haishi” song.

Question 2: What’s the Song About?

What makes a song so powerful that it has brought Dao Lang back into the public’s attention after almost 20 years?

The song carries strong folk and ethnic elements, and the lyrics are quite cryptic. The song itself has the same title as an ironic story in the famous Liaozhai Zhiyi (聊斋志异), or Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, a collection of supernatural and ghostly tales written by Pu Songling (蒲松龄) during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

The song’s sudden popularity is mainly attributed to the mocking implication embedded in the lyrics.

One particular verse, in particular, has sparked significant discussion:

那马户不知道他是一头驴

That Don Kee does not know that he is a donkey

那又鸟不知道他是一只鸡

That Scarlet does not know that she is a whore

勾栏从来扮高雅

Brothels have always pretended to be elegant

自古公公好威名

Since ancient times, eunuchs are fond of their mighty reputation

The terms “Mǎ Hù” (马户) and “Yòu Niǎo” (又鸟), translated here as ‘Don Kee’ and ‘Scarlet’ 1, are not commonly used terms in modern Chinese. Mǎ Hù (马户) is a combination of the characters 马 (mǎ), meaning “horse,” and 户 (hù), meaning “household” or “family.” If these two are combined as one character, you get “驴” (lü), meaning “donkey,” hence the ‘Don Kee’ translation to English.

Similarly, “Yòu Niǎo” (又鸟) is a made-up term consisting of two character components that, when put together, means “chicken” (“鸡”, jī).

Both ‘donkey’ and ‘chicken’ have been used as curses in China. People use phrases such as “as silly as a donkey” (“蠢得像头驴”) to describe foolish behavior. On the other hand, the term “chicken” (鸡) often implies prostitution when used in the singular form, but it can also take on the meaning of “trashy” (辣鸡, a phonetic adaptation of the word 垃圾, rubbish) or “weak” (菜鸡) when combined with other characters.

The term that is translated as “brothel” here is “gōulán” (勾栏), which refers to a type of performance venue for opera in urban areas during the Song and Yuan dynasties but is also used to refer to brothels.

The term “gōng gong” (公公) is used to address the father of one’s spouse, but is also has additional meanings and was historically used as an appellation for eunuchs, (castrated) male servants in the imperial court.

So we could say that the first two lines of these lyrics can be interpreted as mocking or cursing people who are unaware of their own silliness or weak status. When combined with the third and fourth lines, which describe things that are pretentious, we can deduce that these lyrics are meant to point out how some people perceive themselves as much more than they actually are, vainly focused on how they portray themselves to others and their status.

Question 3: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in This Song?

There are various online theories on what or who Dao Lang is actually referring to in this song.

◼︎ One trending theory is that it is about Na Ying (那英). Na Ying is a Chinese singer who rose to national fame after serving as a coach in the the popular television singing show The Voice of China in 2012.

Despite gaining recognition in 2004 for his album The First Snow of 2002 (2003), Dao Lang was not widely celebrated as an artist at that time. When Chinese media asked various artists about their thoughts on the ‘rising star’ Dao Lang, he was often criticized and belittled. Among those with the deepest grudge against Dao Lang, it is widely rumored that Na Ying was the one.

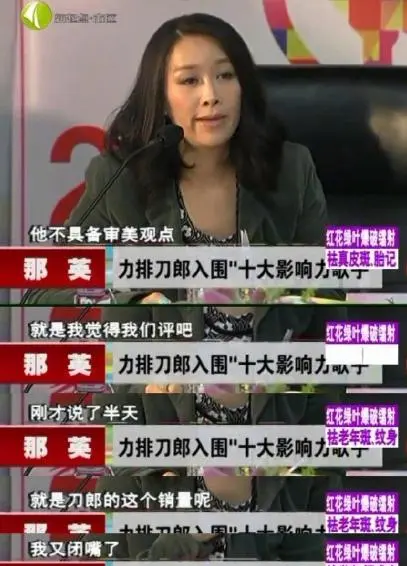

In 2010, during the selection of the “Top 10 Most Influential Singers of the Decade,” Na Ying, as the jury chairwoman, vehemently opposed Dao Lang’s inclusion. She allegedly believed that Dao Lang’s songs lacked aesthetic value, despite their high sales, and that music should not be solely judged based on sales volume.

Na Ying commented that Dao Lang’s songs lack of aesthetic characteristic in the 2013’s show (source).

This publicly known clash with Na Ying has sparked widespread speculation that the person subtly mocked by Dao Lang in his song is actually her. Moreover, some interpret the repetition of the character “那” (nà, “that”) throughout the song as a reference to Na Ying’s surname.

Soon after the album’s release, Na Ying’s social media accounts were inundated with netizens convinced that the song was directed at her. Her follower count on Douyin (Chinese TikTok) surged from 770,000 to 1,800,000, and her recent video garnered millions of comments, with many referencing Dao Lang’s song and blaming her for belittling Dao Lang back in the day.

◼︎ Another trending theory is that Dao Lang is cursing the popular music talent show The Voice of China and its coaching panel. Besides Na Ying, singers Yang Kun and Wang Feng also received ten thousands of comments related to Dao Lang’s song on their social media accounts.

One of the reasons why people think the song refers to the show is because it contains the line “Before speaking, they turn around” (“未曾开言先转腚”), which reminds people of the show’s “chair turning moment” in which coaches, whose chairs are turned away from the blind audition stage, can press a button that turns their chair around to face the stage if they are impressed by the contestant’s voice and want to work with them.

In the 2015 season of “The Voice of China,” Wang Feng, Na Ying, and Yang Kun (from the second left to the right) participated as coaches (image source).

◼︎ A third trending theory suggests that the song’s meaning extends far beyond the music industry and carries geopolitical implications. Some netizens have let their imaginations run wild, arguing that the song is actually mocking the United States. The opening line “The land of Rakshasa extends 26,000 li to the east, crossing the Seven Gorges and the scorched Yellow Mud Land of three inches” (“罗刹国向东两万六千里,过七冲越焦海三寸的黄泥地”) is a point of focus.

Since 26,000 li is a traditional Chinese unit of distance, equivalent to half a kilometer, some believe it aligns precisely with China’s territory. Consequently, they speculate that the Rakshasa country, located 13,000 kilometers west of China, is a metaphor for the United States.

The Aftermath

Amidst the nationwide speculation on whom Dao Lang is targeting in his song, several “suspects” have responded to netizens’ guesses. Some chose to resolve the controversy humorously, while others indirectly expressed their distress over the online abuse stemming from these unfounded speculations. Recent reports indicate that Na Ying, in her latest debut, seemed to be greatly affected by the harsh comments made by netizens.

While the speculations surrounding the song have garnered significant attention for both the song and the singer, some discussions are not necessarily constructive. As some netizens point out, the song might not even aim to curse anyone.

It could also be that the song is simply inspired by one of the stories in the book Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (聊斋志异), which is set in a place called Rakshasa Country, located 26,000 li west of China, resembling a bustling market. In this country, people have peculiar and bizarre appearances, and the more non-human they look, the more attention they receive, while those who appear human live at the bottom of society. Therefore, it is possible that the song aims to narrate these stories instead of attacking someone in particular.

Moreover, the extensive speculations surrounding the song’s intention have also seemingly transformed Dao Lang’s music from a source of enjoyment into a source of analysis, with netizens now meticulously scrutinizing every lyric line.

Among the billions of streams, it begs the question: how many listeners are genuinely enjoying Dao Lang’s music, and how many are just eager sleuths, searching for clues to support their theories about the song’s targets? This raises some curiosity about the true significance of the song’s popularity.

On the other hand, Dao Lang would likely not mind if the song eventually finds its place in the Guinness Book of Records, alongside a note that recognizes it as “the no 1 one most-played hit song that kept everyone guessing.”

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

1. Part of the translation provided, namely the translation of ‘Ma Hu’ 马户 as ‘Don Kee’ and ‘You Niao’ 又鸟 as ‘the scarlet woman’ was created by Xiangdong Zhu & Ning Wan on Wenxuecity.com on August 1st 2023, although the original page has since been deleted.

This article has been edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Part of featured image via Xigua Shipin.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Zilan Qian is a China-born undergraduate student at Barnard College majoring in Anthropology. She is interested in exploring different cultural phenomena, loves people-watching, and likes loitering in supermarkets and museums.

You may like

China Arts & Entertainment

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

Whenever reports surfaced about the harsh conditions on Wong Kar-wai’s sets, mainstream media and fans often brushed off his tyrannical habits as the quirks of a genius. This time, it feels different.

Published

2 weeks agoon

October 3, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

After renowned director Wong Kar-wai was accused of exploiting a young writer during the production of the hit TV drama Blossoms Shanghai, a scandal unfolded that may be one of the biggest stories in China’s entertainment industry this year.

Even if you don’t recognize him by face, you most likely know him by name: Wong Kar-wai (王家卫, 1958), the internationally acclaimed Hong Kong movie director.

Director Wong Kar-wai, characteristically in sunglasses. (Image via Iazimao).

In late 2023, Wong Kar-wai released his first television series, Blossoms Shanghai (繁花), which was referred to a being the third part of an informal Wong Kar-wai trilogy that started with his films In the Mood for Love and 2046. Thanks to its superior production quality, star-studded cast, and Wong Kar-wai’s signature visual style, it became one of the most talked-about Chinese TV dramas of the time.

Scenes from Shanghai Blossom.

Adapted from Jin Yucheng’s award-winning novel, Blossoms Shanghai is set in 1990s Shanghai and tells the story of a young man, A Bao (played by Hu Ge 胡歌), who aspires to become a successful businessman and self-made millionaire during China’s booming reform era. The series contrasts the protagonist’s troubled past with the city’s vibrant present—and even sparked a wave of visitors to Shanghai landmarks featured in the show.

“Overnight, the headline “Wong Kar-wai Suspected of Exploiting Employees” became the biggest story in Chinese entertainment news”

However, in September, screenwriter Gu Er (古二,real name Cheng Junnian 程骏年) stirred controversy when he published a post on his WeChat official account, @GuErNewWords (古二新语), accusing Wong Kar-wai and lead writer Qin Wen (秦雯) of serious exploitation during the production of Blossoms Shanghai.

Qin Wen, image via Tencent News.

Overnight, the headline “Wong Kar-wai Suspected of Exploiting Employees” (王家卫《繁花》被爆疑似压榨员工) became the biggest story in Chinese entertainment news.

Gu Er is an experienced young screenwriter. After earning a master’s degree from the New York Film Academy, he returned to China, where he worked in theater and dabbled in online films. Though he never became a household name, he had carved out a modest presence in the entertainment industry.

According to a series of diaries he began sharing on WeChat in 2022, Gu Er first joined the Blossoms production team in 2019.

Example of Gu Er’s writings, where he talked about the difficult conditions of working on the Blossoms production.

He described the experience as “powered purely by love” (用爱发电)—in other words, long hours, meager pay, and sheer passion keeping him afloat. These early posts detailed many interactions with Wong Kar-wai and lead scriptwriter Qin Wen, but since the drama had not yet aired, his satirical, lightly veiled critiques attracted little attention.

“When the credits rolled, Gu Er’s name was nowhere to be found under the screenwriting slot”

In 2023, upon the premiere of the series, Gu Er published an article titled “The Truth Behind the Writing of Blossoms” (《繁花》剧本的创作真相). In it, he claimed to have written substantial portions of the storyline and character arcs—work that, he said, had been personally approved by Wong.

He also shared chat screenshots and presented several key concepts he had pitched, many of which viewers later recognized in the broadcast series.

Yet when the credits rolled, his name was nowhere to be found under the screenwriting slot. Instead, he was listed only as “preliminary editor” (前期责编), buried at the very end of the credits in a position so minor it was almost negligible.

For Gu Er, this was humiliating. He believed that his field research, character development, and story-building should have earned him recognition as at least one of the principal writers. The post sparked some discussion, but once again, the controversy quickly faded.

Cheng Junnian is Gu Er’s real name, and in the later recordings he posted, Wong Kar-wai also called him by his real name.

It wasn’t until September 16, 2025—nearly two years later—that Gu Er released another definitive essay, “My Experience as a Screenwriter for Blossoms: A Summary” (《我给〈繁花〉做编剧的经历——小结》).

This time, he laid bare every painstaking detail of his creative process for the main female character’s storyline. He claimed that the production refused to reimburse any of his research and interview expenses—not even for meals or books. He recalled one particular moment: “Once I spent 100 yuan [$7], and the Hong Kong producer immediately scolded me in public: ‘How does writing cost any money?’”

“It’s just a few thousand yuan; he is an assistant and can also write the script—it’s a bargain”

Besides writing duties, Gu Er said he also had to cook meals and run endless errands for Wong Kar-wai. In fact, Gu Er suffers from Kennedy’s disease, a motor neuron illness similar to ALS but slower in progression. Like ALS patients, he is gradually losing strength in his limbs. The intense, high-pressure work environment on set made his condition much worse. When he first told Wong Kar-wai about his health, Wong allegedly responded with nothing but suspicion: “What do you want from me?”

Gu Er, image from the time he was a guest chef at Dee Hsu’s reality show.

Wong Kar-wai wasn’t the only person Gu Er accused of exploitation. He also named lead screenwriter Qin Wen, one of the most prominent figures in Chinese television, known for hit dramas such as The First Half of My Life (我的前半生) and My Heroic Husband (赘婿). Qin is also credited as the screenwriter of Blossoms. According to Gu Er, once his draft script was handed to Qin Wen, she “made a few revisions,” and it was then presented as her work.

He further alleged that Qin tried to push him out of the production team, but Wong Kar-wai intervened, saying: “It’s just a few thousand yuan; he is an assistant and can also write the script—it’s a bargain.”

This post finally drew widespread attention. While the public was shocked by the alleged misconduct of a beloved director, many also questioned Gu Er’s credibility.

The Blossoms production team quickly issued a statement, asserting that more than 2,000 crew members had all been properly credited, and later clarified that Gu Er had only been part of the early-stage research team.

“The very type of boss you’d be too afraid to confront in your own workplace”

However, netizens began combing through Gu Er’s WeChat account and discovered that, in recent months, he had uploaded a series of audio recordings of conversations among the production staff—including Wong and Qin.

These recordings became crucial evidence in Gu Er’s defense. In one recording, a producer admitted that Qin had used ghostwriters and that several major plotlines had, in fact, been written by Gu Er. She also acknowledged that it would be difficult for him to receive proper credit.

Other tapes revealed the director’s harsh treatment of crew members; in one instance, Gu Er himself was publicly humiliated and accused of being “a dog using its master’s power” (狗仗人势).

On September 22, Gu Er released another recording. This time, it featured Wong Kar-wai and Qin Wen gossiping about several well-known actors; when the conversation ended, they asked Gu Er to serve them their food.

Having studied at Le Cordon Bleu in San Francisco, Gu Er had apparently been cooking for Wong without pay. Netizens were particularly angered by how arrogant and condescending Wong sounded in the recording, which many said reminded them of the very type of boss they had been too afraid to confront in their own workplaces.

At the same time, netizens dug up a 2024 report from Hong Kong’s Ming Pao (明报), which detailed how a female screenwriter’s script for Blossoms had also allegedly been exploited by Wong Kar-wai. That writer, too, reportedly suffered from depression as a result.

“The Gu Er incident is a snapshot of class solidification”

On September 23, Gu Er’s WeChat account was taken down, rendering all of his articles and audio recordings inaccessible.

Since both WeChat and the parent company of Blossoms’ production house, Tencent Pictures, are owned by Tencent, netizens immediately speculated that the platform had silenced Gu Er to contain the scandal. The move only fueled public suspicion that Wong had indeed exploited young writers—and calls grew louder for an official response from Wong Kar-wai.

As the controversy spread, screenwriter Qin Wen posted a denial on Weibo, insisting that she had been slandered.

Oscar-winning cinematographer Peter Pau (鲍德熹), who worked on Blossoms, also weighed in, saying that all responsibilities had been clearly outlined in the contracts and accusing Gu Er of deliberately stirring trouble. Hong Kong director Wong Jing (王晶) likewise voiced his support for Wong Kar-wai.

However, the broader public—the majority of netizens as well as many within the industry—stood by Gu Er.

The film news account Qiangbaoshan (@誓要抢包山) commented that regardless of the exact truth of Gu Er’s claims, it was already alarming and unjust that major figures in the film industry had banded together to discredit him while his own platform was banned.

Commenters on Xiaohongshu wrote thousands of posts in defense of Gu Er, calling the incident “a snapshot of class solidification,” or writing: “I also stand with Gu Er. Either you hire a proper chef, or you clearly define the work. If someone contributes ideas and creativity, then give them the pay and credit they deserve.”

Gu Er’s friend Ma Nong (玛侬) also published an article on her WeChat official account in his defense, sharing new photos of Gu Er at work and on set to prove that he had indeed played an important role in the Blossoms production.

Yet through it all, to this day, Wong Kar-wai himself has not uttered a single word in response.

“Because of his cinematic achievements, the media and fans often laughed off his tyrannical behavior as the eccentric quirks of a genius”

Some netizens, after learning the details, were puzzled by Gu Er’s behavior. They criticized him as weak and overly servile, suggesting that what he faced now was partly the result of his own personality flaws.

Yet this very dynamic may be why the public’s anger toward Wong Kar-wai ran so deep. Wong is arguably one of the most influential directors in Chinese cinema. Works such as In the Mood for Love, Chungking Express, and Happy Together have left an indelible mark on world cinema and inspired generations of filmmakers. For a relative ‘nobody’ like Gu Er, Wong Kar-wai would have seemed an idol—a god-like figure (Gu Er also expressed his love and admiration for Wong in his previous articles). And it may have been precisely this sense of awe and worship that left Gu Er vulnerable to workplace bullying and manipulation.

Wong Kar-wai’s harsh treatment of his actors and crew has actually never been a secret. Famous actors who previously worked with him, such as Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung, have spoken openly about his extreme working methods. After filming Happy Together, Leslie Cheung announced that he would never work with Wong again, later revealing that he felt the director had exploited his sexuality. During the shoot of Ashes of Time (东邪西毒), Cheung nearly died from poisoning in the desert. Even in their earlier collaborations, he was often tormented by Wong’s constant changes and endless demands.

Wong’s obsessive pursuit of his own has repeatedly come at the expense of those around him. While filming The Grandmaster, he reportedly withheld actress Song Hye-kyo’s passport and kept her on set for months, only to use a handful of shots in the final cut.

Yet, because of his cinematic achievements, the media and fans often laughed off his tyrannical behavior as the eccentric quirks of a genius.

After the Gu Er controversy, however, many began to re-examine the man behind the perpetual sunglasses—not as an untouchable auteur, but as an employer accountable for his power. Wong Kar-wai has long been known for procrastination, perfectionism, and “torturing actors,” but the stakes of this reputation now feel different.

Meanwhile, Gu Er’s WeChat account remains banned. It is difficult to imagine why a man already battling a degenerative illness would continue to fight so publicly for recognition, unless he felt he had nothing left to lose.

Writer Shuimuding (水木丁) raised deeper concerns about Gu Er’s desperate, all-or-nothing stance, reminding readers of the darker history of the Chinese film industry, where young talent has been pushed to despair—and sometimes even to death—by powerful figures. The most haunting example is Hu Bo (胡波), the brilliant director of An Elephant Sitting Still (大象席地而坐), who took his own life after facing similar pressures.

This is why the Wong Kar-wai scandal matters. No matter how talented the director, actual exploitation can never be justified for the sake of the project. Perhaps it is time to stop using exceptional artistic talent as an excuse for unacceptable workplace dynamics.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

Evil Unbound (731): How a Chinese Anti-Japanese War Film Backfired

731 was China’s most anticipated war movie of the year — how could it fail so miserably to live up to public expectations?

Published

3 weeks agoon

September 24, 2025

🔥 This is premium content and also appeared in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

How did Evil Unbound (731), one of the most anticipated Chinese war movies of 2025, go from patriotic hype to online backlash? A deep dive into the official narrative, the audience reception, and everything that’s particular about this movie.

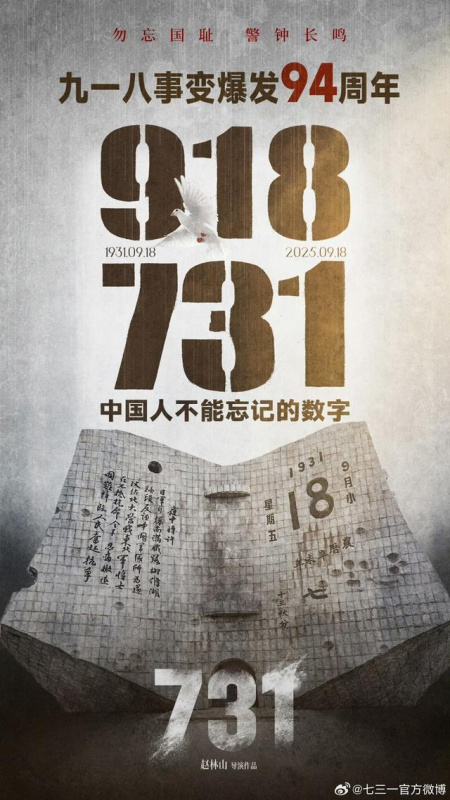

731 and 918, those were the numbers dominating Chinese social media over the past week. Both numbers carry heavy historical weight, but the recent discussions surrounding them reveal two parallel worlds of the official narrative vs the audience experience of a controversial new World War II film.

It was “9.18” on Thursday, when China commemorated the 94th anniversary of the September 18th Incident (九一八事变). On that day in 1931, a small explosion on a Japanese-owned railway near Shenyang (Mukden) was used as a pretext to invade Manchuria.

While many older Chinese were taught in school that the war began in 1937, recent state-led campaigns increasingly emphasize 1931 as the true beginning of China’s “14-year-long war” (1931–1945). Over the past decade, the 918 commemorations have become more prominent online, shaping public memory through nationalistic messaging.

This year, the commemoration had an extra dimension, as it wove the release of Evil Unbound (English title), also known as 731, into the patriotic media narratives around 918.

Patriotic film poster putting 918 and 731 together.

The much-anticipated war movie 731 depicts the atrocities of Japan’s Unit 731 (731部队), notorious for conducting horrific biological warfare experiments in Harbin during World War II under Major General Shiro Ishii (石井四郎), a former army surgeon and biologist with a particular interest in historical plagues. Under his command, Japan’s biological warfare and human experimentation in China were carried out on a larger scale than anywhere else between the 1930s and 1940s.

After the war, because the US felt his knowledge on bioweapons was of great value, Ishii was granted political immunity deal and was never brought to trial.

Together with the Nanjing Massacre, Unit 731 has come to symbolize the peak horrors of Japan’s wartime atrocities. Public attention for this history has grown in recent years, especially since the 2015 opening of the Harbin-based Museum of Evidence of War Crimes by Unit 731.

It was around that same time, about a decade ago, when Chinese director Zhao Linshan (赵林山) started working on the movie Evil Unbound (731), produced by Changchun Film Group in collaboration with the Propaganda Departments of Shandong, Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Harbin.

It finally premiered nationwide on Thursday, ‘9.18’ at exactly 9:18 and shattered 10 box office records on its opening day. Screened 258,000 times in a single day, it rapidly surpassed 200 million yuan (US$28 million) in ticket sales. After three days, the box office exceeded 1 billion yuan (US$140 million).

The film focuses on Unit 731 in the final days before Japan’s defeat in 1945, portraying how local salesman Wang Yongzhang (王永章, played by Jiang Wu 姜武) is imprisoned together with other civilians. They are promised freedom in exchange for “health checks and epidemic prevention cooperation,” and are subjected to frostbite experiments, poison gas, and vivisections.

Official film posters for Evil Unbound/731.

“What we made is not a movie — it is historical evidence,” director Zhao said about the film.

A state-orchestrated hashtag ecosystem is currently amplifying the film’s ‘success.’ Similar to previous viral war film hits such as The Battle at Lake Changjin (长津湖) and Nanjing Photo Studio (Dead to Rights 南京照相馆), the media campaigns highlight the film’s commercial performance, its educational and historical value, the ‘authenticity’ of its production process, and its emotional reception and overseas recognition.

Recent trending hashtags, from Kuaishou to Weibo and beyond, include:

- 电影731票房再创新高 – “Film 731 sets another box office record”

- 没有人能在看731时不流泪 – “No one can watch 731 without crying”

- 观众掩面哭泣 / 哭到没法接受采访 – “Audiences cover faces in tears” or “Audiences too moved to be interviewed”

- 观众自发起立唱国歌 – “Audience spontaneously stand up to sing national anthem”

- 海外观众看731不停抹泪 – “Overseas audiences weeping when seeing 731”

- 9岁小孩看完731后泪奔 – “9-year-old child burst into tears after watching 731”

- 日本观众看完电影731后情绪崩溃 – “Japanese audiences having emotional breakdown after watching 731”

- 让731这段历史不再沉默 – “The history of 731 can no longer be silenced”

There are hundreds of other hashtags contributing to this official narrative, that portrays Evil Unbound as an absolute patriotic and commercial triumph.

From Anticipation to Backlash: 731 Between Shawshank and Squid Game

Outside of this official narrative, however, audiences are telling a very different story. Despite months of anticipation, the film has been met with overwhelmingly negative reviews.

On Weibo, the hashtag “731 Film Review” (#731影评#) was pulled offline. On Douban, the movie’s ratings meter was switched off entirely (“暂无评分”). On IMDb, the film is currently rated 3.1.

Usually, criticism of patriotic films is a slippery slope. People have been censored, blocked, or even detained for criticizing war films. But criticism of this film is so widespread, and so ubiquitous across social media platforms, that it is barely containable.

Many viewers called the movie “trash,” while others said they felt “defrauded”.[1] One commenter suggested the director tried to make The Shawshank Redemption but ended up with Squid Game.[2] Others called it “bizarre”[3], or concluded: “The short review section doesn’t even allow enough characters to describe how unbearable this movie is.”[4]

Viewing the film, I must admit I also felt confused – the movie is nothing like you would expect after the state-led promotion of the film.

The opening minutes quickly set a messy historical context, leaping from the 1925 Geneva Protocol to China’s 1943 counteroffensives, to Iwo Jima, and to Japan’s “Operation PX” plan (Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night), a scheme to attack the United States with biological weapons—before landing in Harbin and Unit 731 in the year 1945.

About ten minutes in, the movie seems to switch tracks and take inspiration from Squid Game, the 2021 South Korean survival drama.

Some details appear almost one-to-one from the Netflix show: the cold speaker voice, characters labeled by numbers, stylized lighting (including the Japanese flag’s red dot turned into menacing red spotlight), and eerily sterile sets that create a cold, clinical atmosphere stripped of humanity.

Scenes from 731.

Narrative elements also echo Squid Game’s deadly competitions, including an actual life-or-death rope pulling game. In 731, “winners” are promised freedom (but actually sent for experiments) and “losers” surviving slightly longer, until even these rules seemingly disappear, leaving viewers just as lost as the characters.

Beyond these echoes of Squid Game and The Shawshank Redemption (with their themes of prison break, brotherhood, and hope), where horror meets drama and occasionally even comedy, I also thought I saw traces of The Green Mile (there’s even a befriended mouse), The Shining, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and even Kill Bill.

If this all sounds like a fever dream, that’s about right.

While the film undoubtedly has artistic value in its visual references and symbolism, at times it seems more intent on presenting itself as an arthouse production than on telling a coherent historical war story.

731 scene showing Japanese flags with red lasers/spotlights one the left. Some of the movie’s camera angle points, color use, narrative elements and settings show some similarities with Squid Game (image on right).

731 (left), Squid Game (right)

Scene from 731, which I thought sometimes had some echoes from The Shining.

Another reference to Stanley Kubrick? 731 on the left, Clockwork Orange on the right.

Prison mouse friend. 731 (left) and The Green Mile (right).

And that is also what most of the online critique is about – people feel that while the movie is supposed to be about creating awareness of a particularly horrific part of Chinese war history, the actual factual history seems to have ended up in the background.

One commenter from Harbin wrote:[5]

💬 “For Harbin, 731 is the most painful chapter of history. This movie uses a mass of absurd visuals and music to tell a story that has almost nothing to do with real history. All the information that truly should have been shown is brushed over in passing words, and in the end it just tells audiences ‘never forget history’? This tramples on the history of 731. Stupid and vulgar.”

Others are also upset over historical inaccuracies in the film — from the makeup to the sets, the props, and the biological experiments. Even the toilet paper used by the prisoners isn’t very realistic, with some commenters saying these kinds of details ‘drove them crazy’:

💬 “I’m born after 1990, and even I grew up with worse toilet paper than what the aggressors in those years apparently gave to their prisoners. Theirs was so high-quality you could fold it into bows and baby shoes. Must have been strong, durable, and waterproof.”[6]

One other reviewer on Douban wrote:

💬 “As a prison break film it’s not exciting, as a historical film it’s too careless, and as a drama it’s too fragmented.”[7]

Douban reviewer Qingyun (青云) noted that it jumps from relatively calm scenes to intense emotional outbursts or extreme cruelty without any buildup — instead of moving viewers to tears, it alienates them from the story and its characters.

He adds:

💬 “The film wants to exploit history’s seriousness to entertain the public, but also fears the theme is too depressing and will affect the box office, so it stuffs in commercial gimmicks (jokes, fantasy, spectacle). This opportunism sacrifices the solemnity that is rewired for the historical topic, while also failing to provide as qualified entertainment. The result: it offends history and disappoints audiences.”[8]

Most of these disappointed reviewers argued that the chance to tell the story of Unit 731 was wasted by a director and script that offered little context to the subject, with some even suggesting that another, 37-year-old film (Men Behind the Sun, 黑太阳731, 1988) did a better job of conveying the history of Japan’s biological warfare in China.

A ‘Masterful Cult Film,’ But a ‘Total Failure’ as a War Movie

Despite the wave of strongly negative feedback, there are also those who did find the film moving, giving it five-star reviews — some from those who stress the film’s value as a reminder to “never forget national humiliation,” while others genuinely appreciate its creative vision.

Douban commenter ‘Bat Lord’ (蝙蝠君) called it a “masterful cult film” with the film’s aesthetics being “built on a foundation of Western stereotypical Orientalism of Japan and layered with Christian martyrdom.”[9]

As an example, Bat Lord describes a recurring scene in which prisoners are taken from their cells toward “freedom,” only to be taken to lethal human experiments. They are escorted by Japanese guards in traditional kimonos with samurai swords, led by a geisha carrying a bright red umbrella and wearing impossibly high okobo clogs, followed by Edo-period guards with topknots and white kimono. Bat Lord calls it “Orientalist punk seen through a Western gaze” (“有一种西方视角的东方主义朋克的味道”).

The reviewer also interprets the main characters, the Chinese prisoners, as representations of Christian martyrdom. Cross symbols are indeed everywhere in the film, with prisoner No. 017 constantly drawing crosses on the wall, and an ingenious escape plan hidden in a dictionary as a series of crosses.

At the climax, after battling guards in kimonos with wooden swords, the prisoners flee toward a crematorium resembling a cathedral of light, where crosses formed from pure white beams symbolize freedom. But behind the cross loom the Japanese executioners. After a bloody massacre, the survivors are captured and executed — tied to crosses arranged around a pit, with fleas dropped on them from above as Japanese officers watch from a grandstand.

Cross symbols appear throughout the film.

💬 “It’s clearly a direct homage to Christian martyrs who were sacrificed in the Colosseum during the ancient Roman Empire. In the end, all the protagonists die martyrs’ deaths,” Bat Lord writes.[10]

He concludes that the film is “4/5 as an art house film, but zero points as a war movie”:

💬 “As a mainstream patriotic commercial blockbuster, it is a complete and utter failure (..) But as a niche cult prank film, it actually has some positive points (…) – built on exaggerated Orientalist visions of Japan, it feels strangely authentic. This kind of deconstruction of Japanese culture isn’t something the Japanese themselves could do — only the West or China, as seen in works like The Last Samurai, Ghost of Tsushima, and Shogun.” [11]

He adds:

💬 “The biggest problem is the subject matter. Using 731 — such a solemn, tragic history — only to hollow out its pain, exploit national emotions, and repackage it as a cult prank film disguised as a patriotic blockbuster, inevitably backfires. If it had been framed as a semi-fictional low-budget black comedy, the backlash wouldn’t be so severe.”[12]

“No Japanese in Heaven”: Over-‘Othering’ the Enemy

How could 731 have failed so miserably to live up to public expectations?

In recent years, Chinese museums, books, and popular culture have made many attempts to revitalize the history of war and make it more relevant to younger generations. In many cases, this has been successful, from popular war dramas to blockbuster films.

But Unit 731 is perhaps an especially difficult subject to adapt into a commercially successful film for a broad audience, especially since it chose to leave out the kind of contextualization that Oppenheimer provided in exploring the history, process, and character development that led to the atomic bomb.

Like the gas chambers of Auschwitz or Mengele’s brutal experiments, its history is so gruesome that there is little to focus on beyond the suffering of the victims and the cruelty of the perpetrators. (The film had already been postponed once, as it allegedly failed to pass official screenings due to its graphic scenes.)

War films in China are expected to reflect — or help shape — national identity. In 731, this means boosting national unity by focusing on Japan as the ultimate “Other,” the ‘constructed outsider’ against which the own national identity is defined.

The entire nation is cast as an enemy, depicted through exaggerated cultural symbols — geishas, kimonos, samurai, and cherry blossoms — regardless of whether they belonged in the actual prison setting. Japan’s national colors and imagery are fused with scenes of bloody and barbaric slaughter, turning Japanese cultural identity itself into a target.

References to Japanese cultural symbols in the film.

In doing so, the film not only holds Japan as a whole responsible for its wartime aggression, but also strengthens Chinese identity by defining it in opposition to Japan, visually contrasting “good” versus “evil” through opposing characters, colors, and symbols.

Clear visual symbols: dead Chinese bodies covered in white dust. With the red circle of blood, the scene resembles a Japanese flag.

This contrast is also made explicit in dialogue: at the beginning of the film, for instance, a young boy enters the stark white prison halls and asks, “Master, are we in heaven?” to which the older Chinese man replies, “Nonsense, how could there be Japanese in heaven?”

In promoting the film, director Zhao Linshan (赵林山) reinforced the image of Japan as the eternal “Other” by explaining that he had insisted none of the Japanese roles could have possibly played by Chinese actors, suggesting they would not be able to convey their evilness. Despite the difficulty of bringing over more than 80 Japanese actors during China’s ‘zero Covid’ era, when 731 was largely filmed, Zhao maintained that “only the Japanese can play this dual nature.”

While Chinese social media is often filled with anti-Japanese sentiment, many viewers criticized the depiction of “Japan” and the Unit 731 staff — not because of the anti-Japanese angle, but because they felt it trivialized history. They argued that Unit 731 was already so horrific that it needed no added gimmicks, tropes, or exaggerated villains to make it look bad.

As Douban reviewer Qingyun wrote:

💬 “Portraying devils as clowns diminishes their true guilt. The real criminals were rational, organized, and intelligent, embodying the will of Japanese militarism as a systematic project. Making them idiots (..) greatly underestimates the danger and organization of militarism, and is a severe simplification of history.”[13]

This critique goes further, suggesting the film both weakens its warning value (“the true terror is that advanced civilization and barbarism can coexist”) and cheapens the victims’ suffering (“if the enemy is so stupid, the tragedy seems less grave”).

On Weibo, one commenter criticized this one-sided approach:

💬 “I saw an auntie in Hangzhou who, after watching the movie 731, said she hated the Japanese devils so much — that she would hate them for her entire life. But this elderly woman, brainwashed by hatred education for a lifetime, doesn’t stop to think that (..) so many other brutal slaughters happened throughout Chinese history. If you only speak of hate, can your hate keep up with all of them? Shouldn’t we instead explore and reflect more deeply on the underlying causes of these events? Better to talk less of hate and more of love — because only the most genuine love from the depths of the human heart can ultimately prevent such tragedies from happening again.”[14]

Some viewers who appreciated the film, however, disagreed. One Weibo user wrote: “I watched the film with my husband and on our way home we scolded the Japanese, wishing we could throw two more atomic bombs on them. It was a good film.”

Between the history and the hate, the official narrative, the polarized audience reactions, and disagreements over the film’s message, 731 has brought more controversy than clarity.

But beyond the debate and confusion, one message remains clear. As one viewer wrote:

“The film wasn’t what I expected, but I’m not sure what I even expected? A good story? More like a documentary? There’s one thing I can say for sure: this movie is just a shell — the history itself is the soul.”[15]

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

References

- “看完有种被诈骗的感觉” (source: Douban).

- “一句话评价《731》,导演按照《肖申克的救赎》拍出了《鱿鱼游戏》” (source: Xiaohongshu).

- “令人非常迷惑” (source: Douban).

- “短评骂的字数不够了实在是忍不了了” (source: Douban).

- “作为一个哈尔滨人,去过至少三次纪念馆,731对于哈尔滨就是最沉痛的一段历史,这个电影用大量极其荒诞的镜头和音乐,讲述一个基本跟真实历史毫无关系的故事,所有真正需要拍出来的信息全部是文字一笔带过,最后却告诉观众勿忘历史?这是对731这段历史的践踏。弱智且下流” (Source: comment section Sina).

- “作为一个90后,我出生的那个年代卫生纸质量都达不到侵略者给实验体使用的,纸的质量太好了,又是编蝴蝶结,又是编鞋子的,我猜应该是坚韧又耐用,透水都不断的那种吧” (Source: Douban long reviews).

- “或许是删减太多或许是各种局限,当做越狱不精彩,当做历史片太随意,当做剧情片太碎片”(Source: Douban).

- “影片既想利用沉重历史的严肃性作为宣传噱头,又担心题材过于压抑影响票房,于是强行注入商业娱乐元素(搞笑、幻想、刺激场面)。这种“既要…又要…”的投机心态导致影片既失去了历史题材必需的敬畏感,又未能提供合格的娱乐体验。最终,它既冒犯了历史,也辜负了观众”(Source Douban, review by Qingyun (青云).

- “西方刻板印象东方主义日本与基督殉难的碰撞,cult片的杰出之作”(Source: Douban, review by ‘Bat Lord’ (蝙蝠君).

- “很明显也在致敬古罗马帝国时期殉道在斗兽场的圣徒们。最终主角团全员殉道,无一幸免。”

- “这个片作为主流主旋律商业大片是完全的,彻头彻尾的失败,彷佛那纯纯的依托!甚至从预告片开始这电影就没有任何一丝一毫的符合历史,我从一开始就完全没有抱任何期望的去看,结果发现这片作为小众邪典整蛊片却颇有可取之处(。。)当你不认为这片是正常电影之后,这片表达出的那股子真的是超正宗的外国视角下的刻板印象东方主义日本美学、东方朋克味,这种对日本文化的魔怔向的解构其实我个人还真感觉挺不错的。这种解构日本人是搞不出来的,目前只有欧美和中国能搞出来,代表作就是《最后的武士》、《对马岛》、《幕府将军》之类的作品,里面的日本文化,日本武士道精神一个赛一个魔怔,欧美是往骑士幻想的那个路子去走的,我们是往黑暗邪典的路子去走的“

- “所以这片的最大问题还是选择了731这个严肃题材,完全在消解历史的悲痛,消费民族的情感,拍了个小众邪典整蛊片后,还按照主流商业片来包装和宣发,如果他拍成半架空的超小成本黑色喜剧我觉得反噬恐怕不会有这么大”(Source: Douban).

- “它美化了真正的邪恶:将恶魔塑造成小丑,实际上减轻了他们的罪责。真实的731部队不是一群疯癫的傻瓜,而是清醒的、有组织的、高智商的罪犯。他们的行为是日本军国主义国家意志的体现,是一个系统性的工程。把他们拍得弱智,仿佛这场悲剧只是一群笨蛋造成的意外,这极大地低估了军国主义的危害性和组织性,是对历史的严重简化”(source: Douban).

- “看到一位杭州阿姨看完电影731后讲太恨日本鬼子了,要一辈子一辈子的恨。这个被仇恨教育洗脑一辈子的老太太,您也不思考一下,嘉定三屠,江东六十四屯,南京大屠杀等等一系列的野蛮屠杀事件在中国历史上发生的太多了,光讲恨您恨的过来吗?不应该是更多的探究和反省发生这些事的深层原因嘛!还是少谈恨多讲爱吧,只有发自心底人类最真实的爱才能最后解决这些惨案在人类世界的发生吧”(Source: Weibo).

- Weibo user “红屋顶上的猫”: “我不知道该怎么评。首先在这个忙乱的日子里安排自己去看这个电影,我也说不清楚我是想铭记那段历史,还是想比较小时候看过的《荒原城堡731》,还有那部《黑太阳》。其次我也不知道电影从越狱视角切入,写实和魔幻风格交替,是好还是不好?但它和我想象的不一样,可我也不知道自己想看到的到底是什么样?甚至我也说不清我对这场电影的期待是什么?讲好故事?还是拍成纪录片?我只能确定,电影只是个壳子,那段历史才是灵魂。”

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

House of Wahaha: Zong Fuli Resigns

How the “Nexperia Incident” Became a Mirror of China–Europe Tensions

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

Nanchang Crowd Confuses Fan for Knife — Man Kicked Down and Taken Away

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Rising Online Movement for Smoke-Free Public Spaces in China

China Trend Watch: Pagoda Fruit Backlash, Tiananmen Parade Drill & Alipay Outage (Aug 11–12)

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral3 months ago

China Memes & Viral3 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature12 months ago

China Books & Literature12 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral10 months ago

China Memes & Viral10 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained