China Fashion & Beauty

Clicking Into the Craze: Exploring the Rise of “Ethnic-Themed Photos” Among Chinese Tourists

Patriotic, problematic, or purely photogenic? The trend of ethnic photoshoots has sprouted across Chinese social media platforms.

Published

2 years agoon

By

Zilan Qian

PREMIUM CONTENT

What looks like a professional photoshoot in a fashion magazine, is actually a local photo service found in one of China’s many popular tourist destinations. Dressing up as various ethnic minorities is not just a souvenir for domestic Chinese travelers; it presents a chance to indulge in a glamorous fantasy.

Exquisitely blushing cheeks, voluminous artificial eyelashes, meticulously styled hairdos, alluring ethnic garments, and enchanting landscapes. These are the captivating elements of the “ethnic-themed photo” (民族风写真) trend that has become increasingly popular on Chinese social media.

The trend is all about Chinese domestic tourists, predominantly young women, who adorn themselves in the traditional attire of China’s ethnic minorities while exploring various regions across the mainland, seeking to capture glamorous moments for their social media posts.

The favored destinations for these photoshoots predominantly encompass regions like Yunnan, Xinjiang, or Tibet— home to various Chinese ethnic communities. For the shoots, they usually wear popular ethnic dresses that are aimed to simulate those worn by people belonging to the Tibetian, Miao, Naxi, or other ethnic groups who each have their own unique cultures and traditional clothing.

Meanwhile, a flourishing industry has emerged to cater to the production of these ethnic photos for tourists. While some visitors simply rent ethnic dresses from shops, many opt for more comprehensive and professional services provided by local photo studios that offer a convenient “one-stop” experience.

Ethnic photos shared by netizens on Xiaohongshu.

Situated in popular tourist destinations, these studios not only provide an extensive selection of ethnic dresses and accessories, but also skilled makeup artists catering to individual preferences, professional photographers capturing moments throughout the daytime excursions, and photo editors perfecting the final photos.

For example, a studio located in Lijiang, Yunnan, promoting its services on the social media app Xiaohongshu, boasts a diverse collection of more than 300 dress choices along with complementary accessories. Their offerings encompass makeup services, ranging from applying false eyelashes and intricate small-scale face painting to skillfully braiding hair.

A studio located in Lijiang advertising on Xiaohongshu. It offers ethnic dresses, makeup, photography, and retouching starting as low as 59 yuan ($8.5).

The studio even promises to deliver the final retouched photos within just 24 hours. Prices for these convenient “one-stop services” differ, starting from less than 100 yuan (approximately US$14) and going up to over 1700 yuan (about US$240). The final cost depends on several factors, including the studio preference, preferred styles, the number of people in the photographs, and the quantity of retouched photos the tourists opt for.

Unique Captures: The Thriving Dress-Up Photography Industry

As the trend of snapping ethnic-inspired photos during trips gains traction in China, the idea of indulging in dress-up photoshoots with stunning makeup and glamorous outfits is not exactly new.

Photography studios specializing in diverse personal portrait services have been a fixture in China for quite a while. These all-inclusive packages usually encompass makeup, hairstyling, outfit selection, backdrop arrangement, skilled photography, and the final retouching.

Some of these studios focus on offering uniquely themed photo shoots, from Tang Dynasty to Disneyland or the magic world of Harry Potter. The customs and backdrops are usually carefully crafted to create extraordinary settings. It is quite common for people to have a series of artistic photos captured for special occasions, such as birthdays, anniversaries, graduations, or weddings (read more about wedding photoshoots in China here).

Haimati (海马体), a trending photography studio, advertising their new styles of Alice in Wonderland and Harry Potter photoshoots.

In recent years, this concept of unique photoshoot experiences has been embraced within the realm of travel. What were previously staged backgrounds painted on canvases have evolved into real tourist attractions, and the studio attire has made way for genuine local outfits. Rather than opting for Disney princesses or Hogwarts students’ costumes, Chinese tourists are now embracing a variety of outfits like kimonos, Hanbok, and Chut Thai as they explore destinations like Japan, South Korea, and Thailand.

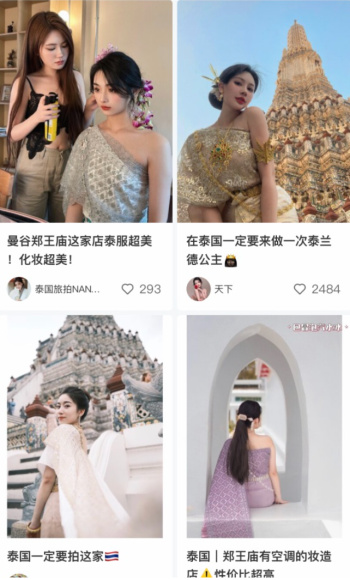

Netizens posting photos of themselves in Chut Thai, traditional Thai clothing, when visiting Thailand on Xiaohongshu.

Netizens posting photos of themselves in Hanbok, the traditional clothing of Korea, when visiting Seoul on Xiaohongshu.

Netizens posting photos of themselves in kimonos when visiting Kyoto and Tokyo on Xiaohongshu.

The popularity of these practices has grown so much that many Chinese internet users have shared stories of mistaking young women wearing kimonos for locals and asking them for directions, only to find out they are fellow Chinese tourists. As one internet user commented on a video featuring people in kimonos in Kyoto, “It seems like around 90% of the people wearing kimonos on the streets of Kyoto are Chinese.”

In answer to this tourist trend, Chinese photography studios have started to broaden their horizons and new industries have sprung up in bustling domestic tourist spots in China. These industries offer comprehensive services similar to those provided by traditional studios, but making the people in the photographs look more exotic, elegant, and enchanting.

Following the Stars and Praising the Country: Embracing Ethnic Attire

While the trend of donning ‘exotic’ outfits for sophisticated photoshoots is not new (and not unique to China), the recent growing popularity of local photoshoots themed around Chinese ethnic minority groups is about more than China’s thriving themed-focused photography industry alone – ethnic-themed photos possess a unique appeal for Chinese travelers.

Chinese social media and celebrities have played a significant role in inspiring numerous people to embrace the ethnic clothing trend. Celebrities like Yang Chaoyue (杨超越) and Mao Xiaotong (毛晓彤) frequently appear in online conversations about ethnic-themed photography. Admiring the beauty of these celebrities in ethnic dresses, many bloggers on Xiaohongshu use their photos as references to analyze outfits and photo filters, aiming to recreate similar styles during their own travels. One Xiaohongshu user excitedly shared, “I can’t believe I achieved the same kind of ethnic look as Yang Chaoyue!” alongside a picture of herself dressed similarly to the Miao ethnic group.

Some individuals take the trend a step further by fully immersing themselves in a fantasy world through dressing up. One Chinese blogger portrays herself as a “playful chieftain’s daughter, beloved by many,” while adorned in ethnic attire. Another, set against a backdrop of snow-covered mountains, describes the liberating sensation of embodying a carefree “daughter of the gods” (神明少女) and a radiant Gesang flower (格桑花) — a bloom cherished by the Tibetan people as a sacred symbol of love and good fortune. To them, ethnic clothing offers an escape from the ordinary routines of daily life, allowing them to embrace a desirable alternate reality within their imaginations.

Furthermore, in contrast to foreign attires such as kimonos, ethnic dresses hold a unique allure as they symbolize the ethnic diversity within China, evoking a sense of patriotism among Chinese travelers.

Recently, numerous videos have emerged featuring bloggers proudly donning traditional clothing from the 55 ethnic groups, apart from the Han majority, with the goal of showcasing ‘the charm of Chinese culture.’

A screenshot from a Bilibili video featuring the blogger wearing traditional costumes of various ethnic minority groups. The video proudly presents itself as “Showcasing the beauty and allure of China’s 56 ethnic groups.”

The growing trend of ethnic photos is being embraced as a way to honor China’s abundant cultural legacy and the essence of being Chinese. “Chinese girls indeed look stunning in red,” one netizen expressed in a blog post featuring photos of her donning a vibrant red Monongalia dress, accompanied by a national flag emoji within the sentence.

A screenshot of the netizen’s Xiaohongshu post.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this trend and its patriotic undertones have garnered support from Chinese state media, with the People’s Daily recognizing ethnic minority-themed photoshoots as a contemporary portrayal of Chinese ethnic traditions, highlighting “the distinct aesthetics inherent in Chinese traditional culture.”

Perpetuating Problematic Portrayals of Ethnic Minorities?

While there may be plenty of positive stemming from the revival of public interest in China’s ethnic minority communities through the ethnic photoshoot trend, there are also some less rose-colored consequences to consider.

Firstly, certain popular ethnic photoshoots might inadvertently perpetuate problematic portrayals of ethnic minority cultures. While ethnic photos claim to provide a glimpse into the cultures of ethnic minorities, their primary focus lies in showcasing the beauty of those being photographed for social media purposes, often at the expense of the authenticity of the minority culture they claim to represent.

The ethnic dresses provided by studios for tourists often display mismatches with local traditions. For instance, some tourists dress up as Tibetans in Miao villages, while studios located in Yunnan, home to major ethnic groups like Yi, Bai, Hani, Zhuang, Dai, and Miao, allow customers to don Uyghur outfits, even though Uyghurs are primarily found in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Additionally, many so-called ethnic dresses are often modified to serve customers’ demands. This may include incorporating elements like black chiffon skirts into traditional Miao attire or introducing ditsy floral patterns to traditional Tibetan dress.

These disparities highlight that the contemporary trend often diverges significantly from the genuine portrayal of the minorities it purports to represent (sometimes, the costumes really have more to do with imaginary minorities than representing actual traditional attire). Instead, it frequently caters more to tourists seeking a fantastical and fun experience rather than fostering genuine insights into local traditions and realities.

A traditional Miao dress posted by China & Asia Cultural Travel (left) and the “Miao dress” provided by a photography studio (right).

A traditional Tibetan dress posted by Tibet Vista (left) and the “Tibetan dress” provided by a photography studio.

As the ethnic photo industry continues to expand, questions also arise concerning its repercussions on local economies and the communities residing within these popular tourist spots.

Accounts from tourists in Lijiang, Yunnan, paint a vivid picture of a bustling scene, where the entire Lijiang old town is alive with visitors seeking opportunities for ethnic-themed photography. One observant netizen notes, “It’s not an exaggeration to say that you can find an ethnic photography studio every ten steps in Lijiang.”

Does this intense enthusiasm for ethnic photos actually serve as a catalyst for local economic growth? Or will it inadvertently reduce the rich cultural experience in these tourist destinations into mere picturesque settings for photography? Is there a risk of these places becoming the next Zibo, experiencing a temporary surge in popularity at the expense of the peaceful lives of local communities, only to eventually face a decline in popularity?

Chinese netizens seem less preoccupied with deeper discussions about the impact of ethnic minority representations and their influence on these tourist destinations. Online conversations are largely dominated by tourists showcasing pretty photos of themselves, while studios vigorously promote their services in a fiercely competitive market.

Photo by Life Photo

生活视觉女子写真摄影.

Where does the future trajectory of the trend of ethnic photos lead? Will it simply continue to exist as another form of exquisite photo service, providing people with an opportunity to escape from mundane life and experiment with different styles for cherished memories? Or will it evolve into something more significant, igniting broader discussions on cultural representations and the far-reaching influence of tourism?

Images via photo studios promoting their services on Taobao.

While some may find the trend problematic and complex, many see it as merely photogenic and fun. In the end, regardless of where the ethnic photo hype ultimately will lead, it crystallizes a moment where the interplay of China’s social media’s lens, the surge in domestic tourism, and the intrigue surrounding ethnic minorities seamlessly intersect. Whether it’s a mere snapshot in time or a lasting chapter, this phenomenon captures a blend of cultural curiosity, social media dynamics, and new Chinese traditions in the digital era.

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

Featured image is part of a ethnic photoshoot in Lhasa in 2021, copyright by What’s on Weibo.

This article has been edited for clarity and commissioned by Manya Koetse.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Zilan Qian is a China-born undergraduate student at Barnard College majoring in Anthropology. She is interested in exploring different cultural phenomena, loves people-watching, and likes loitering in supermarkets and museums.

China ACG Culture

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

Published

3 hours agoon

July 6, 2025

In our last article, we’ve determined how Wakuku’s rise is not just about copying & following in Labubu’s footsteps and more about how China is setting the pace for global pop culture IPs. I now want to give you a small peek into the main characters in the field that are currently relevant.

Even if these dolls aren’t really your thing, you’ll inevitably run into them and everything happening around them.

Before diving into the top trending characters, a quick word on the challenges ahead for Labubu & co:

🚩 Bloomberg Opinion columnist Shuli Ren recently argued that Labubu’s biggest threat isn’t competition from Wakuku or knockoffs like “Lafufu,” but the fragility of its resale ecosystem — particularly how POP MART balances supply, scarcity, and reseller control.

Scarcity is part of what makes Labubu feel premium. But if too many dolls go to scalpers, it alienates real fans. If scalpers can’t profit, Labubu risks losing its luxury edge. Managing this dynamic may be POP MART’s greatest long-term challenge.

🚩 Chinese Gen Z consumers value authenticity — and that’s something money can’t manufacture. If China’s booming IP toy industry prioritizes speed and profit over soul, the hype may die out at a certain point.

🚩 The same goes for storytelling. Characters need a solid universe to grow in. Labubu had years to build out its fantasy universe. Cute alone isn’t enough — characterless toys don’t leave a lasting impression and don’t resonate with consumers.

Examples of popularity rankings of Chinese IP toys on Xiaohongshu.

With that in mind… let’s meet the main players.

On platforms like Xiaohongshu, Douyin, and Weibo, users regularly rank the hottest collectible IPs. Based on those rankings, here’s a quick who’s-who of China’s current trend toy universe:

1. Labubu (拉布布)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Kasing Lung

Year launched: 2015 (independent), 2019 with POP MART.

The undisputed icon of China’s trend toy world, Labubu is a mischievous Nordic forest troll with big eyes, nine pointy teeth, and bunny ears. Its quirky, ugly-cute design, endless possibilities of DIY costume changes, and viral celebrity endorsements have made it a must-have collectible and a global pop culture phenomenon.

2. Wakuku (哇库库)

Brand & Creator: Letsvan, backed by QuantaSing Group

Year launched: 2024 with first blind box

Wakuku, a “tribal jungle hunter” with a cheeky grin and unibrow, is seen as the rising star in China’s trend toy market. Wakuku’s rapid rise is fueled by celebrity marketing, pop-up launches, and its strong appeal among Gen Z, especially considering Wakuku is more affordable than Labubu.

3. Molly (茉莉)

Brand: POP MART

Designer: Kenny Wong (王信明)

Year launched: 2006 (creator concept); POP MART 2014, first blind boxes in 2016

Molly is a classic trend toy IP, one of POP MART’s favorites, with a massive fanbase and long-lasting popularity. The character was allegedly inspired by a chance encounter with a determined young kid at a charity fundraiser event, after which Kenny Wong created Molly as a blue-eyed girl with short hair, a bit of a temperament, and an iconic pouting expression that never leaves her face.

4. SKULLPANDA (骷髅熊猫)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Chinese designer Xiong Miao

Year launched: 2018 (creator concept); POP MART 2020

Skullpanda is one of POP MART’s flagship IPs —it’s a goth-inspired fantasy design. According to POP MART, SKULLPANDA journeys through different worlds, taking on various personas and living out myriad lives. On this grand adventure, it’s on a quest to find its truest self and break new ground all while contemplating the shape of infinity.

5. Baby Zoraa

Brand: TNT SPACE

Creator: Wang Zequn, CEO of TNT SPACE

Year launched: 2022, same year as company launch

Baby Zoraa is cute yet devlish fierce and is one of the most popular IPs under TNT SPACE. Baby Zoraa is the sister of Boy Rayan, another popular character under the same brand. Baby Zoraa’s first blind box edition reached #1 on Tmall’s trend toy sales charts and sold over 500,000 units.

6. Dora (大表姐)

Brand: TNT SPACE

Year Launched: 2023

Dora is a cool, rebellious “big sister” figure, instantly recognizable for her bold attitude and expressive style. She’s a Gen Z favorite for her gender-fluid, empowering persona, and became a breakout sucess under TNT when it launched its bigger blind boxes in 2023.

7. Twinkle Twinkle [Star Man] (星星人)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Illustrators Daxin and Ali

Year launched: In 2024 with POP MART

This character has recently skyrocketed in popularity as a “healing star character” inspired by how stars shine even in darkness. POP MART markets this character as being full of innocence and fantasy to provide some relaxation in this modern society full of busyness and pressure.

8. Hirono (小野)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Lang

Year launched: In 2024 with POP MART

This freckled, perpetually grumpy boy has a wild spirit combining introversion and playful defiance. Hirono highlights the subtle fluctuations of life, its ups and downs, incorporating joy, sadness, fear, and more – a personification of profound human emotions.

9. Crybaby (哭娃)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Thai artist Molly Yllom (aka Nisa “Mod” Srikamdee)

Year launched: 2017 (creator concept), 2023 POP MART launch

Like Wakuku, Crybaby suddenly went from a niche IP to a new hot trend toy in 2025. Together with Wakuku, it is called the “next Labubu.” Thai artist Molly Yllom created the character after the loss of her beloved dog. Crybaby is a symbol of emotional expression, particularly the idea that it’s okay to cry and express feelings.

10. Pouka Pouka (波卡波卡)

Brand: 52TOYS

Creator: Ma Xiaoben

Year launched: 2025

With its round, chubby face, squirrel cheeks, playful smile, and soft, comforting appearance, Pouka Pouka aims to evoke feelings of warmth, healing, and emotional comfort.

Other characters to watch: CiciLu, Panda Roll (胖哒幼), NANCI (囡茜), FARMER BOB (农夫鲍勃), Rayan, Ozai (哦崽), Lulu the Piggy (LuLu猪), Pucky (毕奇).

We’re still working on this list!

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China ACG Culture

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

From ugly-cute rebellion to a new kind of ‘C-pop,’ the breakout success of Wakuku sheds light on Chinese consumer culture and the forces driving China’s trend toy industry.

Published

5 hours agoon

July 6, 2025

Wakuku is the most talked-about newcomer in China’s trend toy market. Besides its mischievous grin, what’s perhaps most noteworthy is how closely Wakuku follows the marketing success of Labubu. As the strongest new designer toy of 2025, Wakuku says a lot about China’s current creative economy — from youth-led consumer trends to hybrid business models.

As it is becoming increasingly clear that Chinese designer toy Labubu has basically conquered the world, it’s already time for the next made-in-China collectible toy to start trending on Chinese social media.

Now, the name that’s trending is Wakuku, a Chinese trend toy created by the Shenzhen-based company Letsvan.

In March 2025, a new panda-inspired Wakuku debuted at Miniso Land in Beijing, immediately breaking records and boosting overall store revenue by over 90%. Wakuku also broke daily sales records on May 17 with the launch of its “Fox-and-Bunny” collab at Miniso flagship stores in Shanghai and Nanjing. At the opening of the Miniso Space in Nanjing on June 18, another Wakuku figure sold out within just two hours. Over the past week, Wakuku went trending on Chinese social media multiple times.

From left to right: the March, May, and June successful Wakuku series/figurines

Like Labubu, Wakuku is a collectible keychain doll with a soft vinyl face and a plush body. These designer toys are especially popular among Chinese Gen Z female consumers, who use them as fashion accessories (hanging them from bags) or as desk companions.

We previously wrote in depth about the birth of Labubu, its launch by the Chinese POP MART (founded 2010), and the recipe for its global popularity in this article, so if you’re new to this trend of Chinese designer toys, you’ll want to check it out first (link).

Labubu has been making international headlines for months now, with the hype reaching a new peak when a human-sized Labubu sold for a record 1.08 million RMB (US$150,700), followed by a special edition that was purchased for nearly 760,000 RMB (US$106,000).

Now, Wakuku is the new kid on the block, and while it took Labubu nine years to win over young Chinese consumers, it barely took Wakuku a year — the character was created in 2022–2023, made its retail debut in 2024, and went viral within months.

Its pricing is affordable (59–159 RMB, around $8.2-$22) and some netizens argue it’s more quality for money.

While Labubu is a Nordic forest elf, Wakuku is a tribal jungle warrior. It comes in various designs and colors depending on the series and is sold in blind boxes (盲盒), meaning buyers don’t know exactly which design they’re getting — which adds an element of surprise.

➡️ There’s a lot to say about Wakuku, but perhaps the most noteworthy aspect is how closely it mirrors the trajectory of POP MART’s Labubu.

Wakuku’s recent success in China highlights the growing appeal and rapid rise of Chinese IPs (beyond its legal “intellectual property” meaning, ‘IPs’ is used to refer to unique cultural brands, characters, or stories that can be developed into collectibles, merchandise, and broader pop culture phenomena).

Although many critics predict that the Labubu trend will blow over soon, the popularity of Wakuku and other Labubu-like newcomers shows that these toys are not just a fleeting craze, but a cultural phenomenon that reflects the mindset of young Chinese consumers, China’s cross-industry business dynamics, and the global rise of a new kind of ‘C-pop.’

Wakuku: A Cheeky Jungle Copycat

When I say that Wakuku follows POP MART’s path almost exactly, I’m not exaggerating. Wakuku may be portrayed as a wild jungle child, but it’s definitely also a copycat.

It uses the same materials as Labubu (soft vinyl + plush), the name follows the same ABB format (Labubu, Wakuku, and the panda-themed Wakuku Pangdada), and the character story is built on a similar fantasy universe.

In fact, Letsvan’s very existence is tied to POP MART’s rise — the company was only founded in 2020, the same year POP MART, then already a decade old, went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and became a dominant industry force.

In terms of marketing, Wakuku imitates POP MART’s strategy: blind boxes, well-timed viral drops, limited-edition tactics, and immersive retail environments.

It even follows a similar international expansion model as POP MART, turning Thailand into its first stop (出海首站) — not just because of its cultural proximity and flourishing Gen Z social media market, but also because Thailand was one of the first and most successful foreign markets for Labubu.

Its success is also deeply linked to celebrity endorsement. Just as Labubu gained global traction with icons like BLACKPINK’s Lisa and Rihanna seen holding the doll, Wakuku too leans heavily on celebrity visibility and entertainment culture.

Like Labubu, Wakuku even launched its own Wakuku theme song.

Since 2024, Letsvan has partnered with Yuehua Entertainment (乐华娱乐) — one of China’s leading talent agencies — to tap into its entertainment resources and celebrity network, powering the Wakuku marketing engine. Since stars like Esther Yu (虞书欣) were spotted wearing Wakuku as a jeans hanger, demand for the doll skyrocketed. Yuehua’s founder, Du Hua (杜华), even gifted a Wakuku to David Beckham as part of its celebrity strategy.

From Beckham to Esther Yu; celebrity endorsements play a big role in the viral marketing of Wakuku.

But what’s most important in Wakuku’s success — and how it builds on Labubu — is that it fully embraces the ugly-cute (丑萌 chǒu méng) aesthetic. Wakuku has a mischievous smile, expressive eyes, a slightly crooked face, a unibrow, and freckles — fitting perfectly with what many young Chinese consumers love: expressive, anti-perfectionist characters (反精致).

“Ugly-Cute” as an Aesthetic Rebellion

Letsvan is clearly riding the wave of “ugly trend toys” (丑萌潮玩) that POP MART spent years cultivating.

🔍 Why are Chinese youth so obsessed with things that look quirky or ugly?

A recent article by the Beijing Science Center (北京科学中心) highlights how “ugly-cute” toys like Labubu and Wakuku deviate from traditional Chinese aesthetics, and reflect a deeper generational pushback against perfection and societal expectations.

The pressure young people face — in education, at work, from family expectations, and information overload — is a red thread running through how China’s Gen Z behaves as a social media user and consumer (also see the last newsletter on nostalgia core).

To cope with daily stress, many turn to softer forms of resistance, such as the “lying flat” movement or the sluggish “rat lifestyle” in which people reject societal pressures to succeed, choosing instead to do the bare minimum and live simply.

This generational pushback also extends to traditional norms around marriage, gender roles, and ideals of beauty. Designer toys like Labubu and Wakuku are quirky, asymmetrical, gender-fluid, rebellious, and reflect a broader cultural shift: a playful rejection of conformity and a celebration of personal expression, authenticity, and self-acceptance.

Another popular designer toy is Crybaby, designed by Thai designer Molly, and described as follows: “Crybaby is not a boy or a girl, it is not even just human, it represents an emotion that comes from deep within. It can be anything and everything! Laughter isn’t the only way to make you feel better, crying can be healing too. If one day, a smile can’t alleviate your problems, baby, let’s cry together.”

But this isn’t just about rejecting tradition. It’s also about seeking happiness, comfort, and surprise: emotional value. And it’s usually not brand-focused but influencer-led. What matters is the story around it and who recommends it (unless the brand becomes the influencer itself — which is what’s ultimately happening with POP MART).

One of the unofficial ambassadors of the chǒu méng ugly-cute trend is Quan Hongchan (全红婵), the teenage diving champion and Olympic gold medallist from Guangdong. Quan is beloved not just for her talent, but also for her playful, down-to-earth personality.

During the Paris Olympics, she went viral for her backpack, which was overflowing with stuffed animals (some joked she was “carrying a zoo on her back”) — and for her animal-themed slippers, including a pair of ugly fish ones.

Quan Hongchan with her Wakuku, and her backpack and slippers during her Paris Olympics days.

It’s no surprise that Quan Hongchan is now also among the celebrities boosting the popularity of the quirky Wakuku.

From Factory to Fandom: A New Kind of “C-pop” in the Making

The success of Wakuku and other similar toys shows that they’re much more than Labubu 2.0; they’re all part of a broader trend tapping into the tastes and values of Chinese youth — which also speaks to a global audience.

And this trend is serious business. POP MART is one of the world’s fastest-growing consumer brands, with a current market value of approximately $43 billion, according to Morgan Stanley.

No wonder everyone wants a piece of the ‘Labubu pie,’ from small vendors to major companies.

It’s not just the resellers of authentic Labubu dolls who are profiting from the trend — so are the sellers of ‘Lafufu,’ a nickname for counterfeit Labubu dolls, that have become ubiquitous on e-commerce platforms and in toy markets (quite literally).

Wakuku’s rapid rise is also a story of calculated imitation. In this case, copying isn’t seen as a flaw but as smart market participation.

The founding team behind Letsvan already had a decade of experience in product design before setting out on their journey to become a major player in China’s popular designer toy and character merchandise market.

But their real breakthrough came in early 2025, when QuantaSing (量子之歌), a leading adult learning ed-tech company with no previous ties to toys, acquired a 61% stake in the company.

With QuantaSing’s financial backing, Yuehua Entertainment’s marketing power, and Miniso’s distribution reach, Wakuku took it to the next level.

The speed and precision with which Letsvan, QuantaSing, and Wakuku moved to monetize a subcultural trend — even before it fully peaked — shows just how advanced China’s trend toy industry has become.

This is no longer just about cute (or ugly-cute) designs; it’s about strategic ecosystems by ‘IP factories,’ from concept and design to manufacturing and distribution, blind-box scarcity tactics, immersive store experiences, and influencer-led viral campaigns — all part of a roadmap that POP MART refined and is now adopted by many others finding their way into this lucrative market. Their success is powered by the strength of China’s industrial & digital infrastructure, along with cross-industry collaboration.

The rise of Chinese designer toy companies reminds of the playbook of K-pop entertainment companies — with tight control over IP creation, strong visual branding, carefully engineered virality, and a deep understanding of fandom culture. (For more on this, see my earlier explanation of the K-pop success formula.)

If K-pop’s global impact is any indication, China’s designer toy IPs are only beginning to show their potential. The ecosystems forming around these products — from factory to fandom — signal that Labubu and Wakuku are just the first wave of a much larger movement.

– By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

Jiehun Huazhai (结婚化债): Getting Married to Pay Off Debts

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Media12 months ago

China Media12 months agoA Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoThe “City bu City” (City不City) Meme Takes Chinese Internet by Storm

-

China Society9 months ago

China Society9 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media