China Arts & Entertainment

Behind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

What’s behind the Dao Lang hit song that has everyone talking these days?

Published

12 months agoon

By

Zilan Qian

“Who is being mocked and cursed in this song?” This question has ignited a wildfire of speculation across the Chinese internet, as a recently released folk song by a relatively low-profile singer has amassed a staggering 8 billion plays, surpassing the success of previous hit songs.

A newly released Chinese song, composed and sung by a 52-year-old singer who was primarily active in the 2000s, has achieved an astounding milestone of 8 billion streams in less than two weeks since its release.

The song, titled “Luosha Haishi” (罗刹海市; “Raksha Sea Market” or “Luocha Kingdom”), has been widely acclaimed on various social media platforms, with many claiming that it has surpassed the Guinness World Record for the most streamed track worldwide, a record previously held by “Despacito” in 2017 with 5.5 billion plays. The official Weibo account of Guinness World Records recently stated that they haven’t received any application for a new record yet, and thus, no record has been officially confirmed broken at this time.

However, even 8 billion plays alone are enough to marvel at. The sudden surge in popularity of a song created by a low-profile singer, who has not participated in any major shows or held performances for the last few decades, has raised numerous questions: Who is the singer? What is in the song? And why has it become viral in China? We’ll answer some of these questions for you here.

Question 1: Who is Dao Lang?

Dao Lang (刀郎), whose real name is Luo Lin (罗林), embarked on his musical journey at a young age. Born in 1971, he made the decision to leave school at the age of 17 and fully immerse himself in learning keyboard instruments at a music hall in Neijiang. Over the next four years, he ventured to different locations such as Chengdu, Chongqing, Tibet, and Xi’an, where he gained experience and honed his musical skills. Throughout the 1990s, he actively participated in various music projects and bands, shaping his career in the music industry.

In 2004, Dao Lang’s album The First Snow of 2022 (2002年的第一场雪) was unexpectedly well-received, winning him nationwide popularity. After enjoying success with previous albums, Dao Lang diversified his musical endeavors, collaborating with other artists and exploring different genres, such as folk and ethnic music. Between 2010 and 2012, he participated in various performances and events, including appearing at Hong Kong singer Alan Tam’s concert and the Television Arts Evening Celebration for the 90th Anniversary of the Communist Party of China’s founding.

Dao Lang (Weibo).

Subsequently, Dao Lang appeared to withdraw from social media, only resurfacing with two albums in 2020 and 2021, which were released with minimal promotion. However, it is his latest album, titled There Are Few Folk Songs (山歌寥哉) that has brought him back into the public eye, primarily due to the “Luosha Haishi” song.

Question 2: What’s the Song About?

What makes a song so powerful that it has brought Dao Lang back into the public’s attention after almost 20 years?

The song carries strong folk and ethnic elements, and the lyrics are quite cryptic. The song itself has the same title as an ironic story in the famous Liaozhai Zhiyi (聊斋志异), or Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, a collection of supernatural and ghostly tales written by Pu Songling (蒲松龄) during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

The song’s sudden popularity is mainly attributed to the mocking implication embedded in the lyrics.

One particular verse, in particular, has sparked significant discussion:

那马户不知道他是一头驴

That Don Kee does not know that he is a donkey

那又鸟不知道他是一只鸡

That Scarlet does not know that she is a whore

勾栏从来扮高雅

Brothels have always pretended to be elegant

自古公公好威名

Since ancient times, eunuchs are fond of their mighty reputation

The terms “Mǎ Hù” (马户) and “Yòu Niǎo” (又鸟), translated here as ‘Don Kee’ and ‘Scarlet’ 1, are not commonly used terms in modern Chinese. Mǎ Hù (马户) is a combination of the characters 马 (mǎ), meaning “horse,” and 户 (hù), meaning “household” or “family.” If these two are combined as one character, you get “驴” (lü), meaning “donkey,” hence the ‘Don Kee’ translation to English.

Similarly, “Yòu Niǎo” (又鸟) is a made-up term consisting of two character components that, when put together, means “chicken” (“鸡”, jī).

Both ‘donkey’ and ‘chicken’ have been used as curses in China. People use phrases such as “as silly as a donkey” (“蠢得像头驴”) to describe foolish behavior. On the other hand, the term “chicken” (鸡) often implies prostitution when used in the singular form, but it can also take on the meaning of “trashy” (辣鸡, a phonetic adaptation of the word 垃圾, rubbish) or “weak” (菜鸡) when combined with other characters.

The term that is translated as “brothel” here is “gōulán” (勾栏), which refers to a type of performance venue for opera in urban areas during the Song and Yuan dynasties but is also used to refer to brothels.

The term “gōng gong” (公公) is used to address the father of one’s spouse, but is also has additional meanings and was historically used as an appellation for eunuchs, (castrated) male servants in the imperial court.

So we could say that the first two lines of these lyrics can be interpreted as mocking or cursing people who are unaware of their own silliness or weak status. When combined with the third and fourth lines, which describe things that are pretentious, we can deduce that these lyrics are meant to point out how some people perceive themselves as much more than they actually are, vainly focused on how they portray themselves to others and their status.

Question 3: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in This Song?

There are various online theories on what or who Dao Lang is actually referring to in this song.

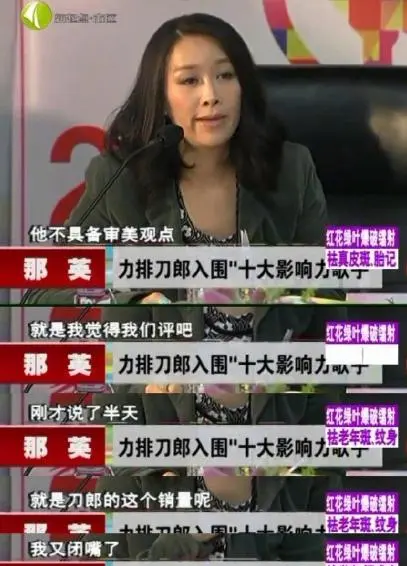

◼︎ One trending theory is that it is about Na Ying (那英). Na Ying is a Chinese singer who rose to national fame after serving as a coach in the the popular television singing show The Voice of China in 2012.

Despite gaining recognition in 2004 for his album The First Snow of 2002 (2003), Dao Lang was not widely celebrated as an artist at that time. When Chinese media asked various artists about their thoughts on the ‘rising star’ Dao Lang, he was often criticized and belittled. Among those with the deepest grudge against Dao Lang, it is widely rumored that Na Ying was the one.

In 2010, during the selection of the “Top 10 Most Influential Singers of the Decade,” Na Ying, as the jury chairwoman, vehemently opposed Dao Lang’s inclusion. She allegedly believed that Dao Lang’s songs lacked aesthetic value, despite their high sales, and that music should not be solely judged based on sales volume.

Na Ying commented that Dao Lang’s songs lack of aesthetic characteristic in the 2013’s show (source).

This publicly known clash with Na Ying has sparked widespread speculation that the person subtly mocked by Dao Lang in his song is actually her. Moreover, some interpret the repetition of the character “那” (nà, “that”) throughout the song as a reference to Na Ying’s surname.

Soon after the album’s release, Na Ying’s social media accounts were inundated with netizens convinced that the song was directed at her. Her follower count on Douyin (Chinese TikTok) surged from 770,000 to 1,800,000, and her recent video garnered millions of comments, with many referencing Dao Lang’s song and blaming her for belittling Dao Lang back in the day.

◼︎ Another trending theory is that Dao Lang is cursing the popular music talent show The Voice of China and its coaching panel. Besides Na Ying, singers Yang Kun and Wang Feng also received ten thousands of comments related to Dao Lang’s song on their social media accounts.

One of the reasons why people think the song refers to the show is because it contains the line “Before speaking, they turn around” (“未曾开言先转腚”), which reminds people of the show’s “chair turning moment” in which coaches, whose chairs are turned away from the blind audition stage, can press a button that turns their chair around to face the stage if they are impressed by the contestant’s voice and want to work with them.

In the 2015 season of “The Voice of China,” Wang Feng, Na Ying, and Yang Kun (from the second left to the right) participated as coaches (image source).

◼︎ A third trending theory suggests that the song’s meaning extends far beyond the music industry and carries geopolitical implications. Some netizens have let their imaginations run wild, arguing that the song is actually mocking the United States. The opening line “The land of Rakshasa extends 26,000 li to the east, crossing the Seven Gorges and the scorched Yellow Mud Land of three inches” (“罗刹国向东两万六千里,过七冲越焦海三寸的黄泥地”) is a point of focus.

Since 26,000 li is a traditional Chinese unit of distance, equivalent to half a kilometer, some believe it aligns precisely with China’s territory. Consequently, they speculate that the Rakshasa country, located 13,000 kilometers west of China, is a metaphor for the United States.

The Aftermath

Amidst the nationwide speculation on whom Dao Lang is targeting in his song, several “suspects” have responded to netizens’ guesses. Some chose to resolve the controversy humorously, while others indirectly expressed their distress over the online abuse stemming from these unfounded speculations. Recent reports indicate that Na Ying, in her latest debut, seemed to be greatly affected by the harsh comments made by netizens.

While the speculations surrounding the song have garnered significant attention for both the song and the singer, some discussions are not necessarily constructive. As some netizens point out, the song might not even aim to curse anyone.

It could also be that the song is simply inspired by one of the stories in the book Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (聊斋志异), which is set in a place called Rakshasa Country, located 26,000 li west of China, resembling a bustling market. In this country, people have peculiar and bizarre appearances, and the more non-human they look, the more attention they receive, while those who appear human live at the bottom of society. Therefore, it is possible that the song aims to narrate these stories instead of attacking someone in particular.

Moreover, the extensive speculations surrounding the song’s intention have also seemingly transformed Dao Lang’s music from a source of enjoyment into a source of analysis, with netizens now meticulously scrutinizing every lyric line.

Among the billions of streams, it begs the question: how many listeners are genuinely enjoying Dao Lang’s music, and how many are just eager sleuths, searching for clues to support their theories about the song’s targets? This raises some curiosity about the true significance of the song’s popularity.

On the other hand, Dao Lang would likely not mind if the song eventually finds its place in the Guinness Book of Records, alongside a note that recognizes it as “the no 1 one most-played hit song that kept everyone guessing.”

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

1. Part of the translation provided, namely the translation of ‘Ma Hu’ 马户 as ‘Don Kee’ and ‘You Niao’ 又鸟 as ‘the scarlet woman’ was created by Xiangdong Zhu & Ning Wan on Wenxuecity.com on August 1st 2023, although the original page has since been deleted.

This article has been edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Part of featured image via Xigua Shipin.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Zilan Qian is a China-born undergraduate student at Barnard College majoring in Anthropology. She is interested in exploring different cultural phenomena, loves people-watching, and likes loitering in supermarkets and museums.

Also Read

China Arts & Entertainment

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

“I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like listening to Alicia Keys.” Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers.

Published

2 months agoon

May 17, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Besides memes and jokes, Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers on Chinese social media.

In May, while the whole of Europe was gripped by the Eurovision Song Contest frenzy, Chinese audiences were eagerly anticipating the return of their own beloved singing competition, Singer 2024 (@湖南卫视歌手), formerly known as I Am a Singer (我是歌手).

The show, introduced from South Korea’s MBC Television and popular in China since 2013, only features professional singers who have already made a name for themselves.

Rather than watching unknown aspiring singers who are hoping to be discovered in many singing competitions, such as Sing! China, Singer 2024 gives audiences a show filled with professional and often stunning show performances by established names in the entertainment industry.

Since 2013, renowned singers from China and abroad have appeared on the show, including Chinese vocalist Tan Jing (谭晶), British pop singer Jessie J, and the late Hong Kong pop diva Coco Lee. However, no season managed to create as many waves as the 2024 season did, dominating all social media trending topics overnight.

So, what exactly happened?

COMPETING WITH FOREIGNERS

“The difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival”

In early May, the pre-show promotion of Singer 2024 was already buzzing on Chinese social media after a list of featured singers appeared on Weibo, including big names such as American singer-songwriter Bruno Mars, Korean-New Zealand singer Rosé from Blackpink, and Japanese diva LiSA.

Although Singer previously had many foreign singers on the show, this international celebrity lineup still caused a stir.

On the day of the first episode, only two foreign singers were announced to appear on the show: young Moroccan-Canadian singer Faouzia and the Grammy-nominated American singer-songwriter Chanté Moore. The other contestants were all Chinese singers who are already well-known among Chinese audiences. Because many people were unfamiliar with the two foreign singers, they joked that the winner of this season was already set in stone; surely it would be the famous Chinese singer Na Ying (那英), known for her beautiful voice.

However, that first episode surprised everyone as the two foreign singers, Faouzia and Chanté Moore, showed outstanding vocal skills. This not only startled many viewers but also made the Chinese contestants uneasy. Several experienced Chinese singers apparently were so unnerved after watching Faouzia and Chanté Moore’s performance that their voices trembled when singing.

Since the show was broadcast live – without post-production editing or autotune – audiences got to hear the actual vocal capabilities and see performers’ genuine reactions. It seemed undeniable that the foreign contestants did much better in terms of vocals and stage presence than the Chinese ones. Some online commenters even said that the gap between Chinese and foreign singers’ levels was like “the difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival” [a local Chinese music festival].

Chinese online influencer Yongkai (@陈咏开165) shared screenshots of Chanté Moore’s backstage reactions during the show. The American celebrity seemed puzzled when hearing the somewhat underwhelming performance by Chinese singer Yang Chenglin (楊丞琳), and she appeared much more positive when Na Ying sang.

This noteworthy scene, coupled with Chanté’s comments during an interview saying that she thought the Chinese production team had invited her on the show to be a judge, turned the entire show into a display of foreign singers outshining the Chinese contestants.

By the end of the first episode, Chanté Moore and Faouzia unsurprisingly ranked first and second, with Na Ying in third place.

After the show, some online commenters jokingly pointed out that Na Ying, being of Manchu descent like the rulers of China during the Qing Dynasty, showed some similarities to Empress Dowager Cixi’s defiance against Western colonizers in the way she “single-handedly took up against on foreigners” on the show.

They humorously turned Na Ying’s expressions into memes resembling Empress Dowager Cixi from an old Chinese TV show, with captions like “I want the foreigners dead” (“我要洋人死”).

Others suggested finding better Chinese singers for the show who could compete with Faouzia and Moore.

“SINGING WELL” CULTURALLY COLONIZED?

“I’m in Zibo eating BBQ, I really don’t want to listen to Alicia Keys.”

Initially, discussions about the show were light-hearted and humorous, until some netizens who couldn’t appreciate the jokes began to dampen the mood and made online discussions more serious.

Zou Xiaoying (@邹小樱), a music critic with nearly two million followers, posted on social media after the show, stating that he would have never voted for Chanté Moore or Faouzia. Not only did Zou question their vocal talent, he also wondered if the aesthetic of Chinese listeners had been influenced by Western music taste to such an extent that it has been “culturally colonized” (“文化殖民”). Meanwhile, he praised the members of Beijing rock band Second Hand Rose as “national heroes” (“民族英雄”).

He wrote:

If I had three votes for the first episode of “Singer 2024,” I’d vote for Second Hand Rose, Na Ying, and Silence Wang [note: Chinese singer-songwriter and record producer Wang Sushuang 汪苏泷]. The reason I wouldn’t vote for Chanté Moore or Faouzia is because — do they actually sing so well?

Has our definition of “singing well” perhaps been colonized? Just as our modern-day use of Chinese has little to do with our classical Chinese poems, with the foundation of modern Chinese actually being translations from the 20th century, is this also a form of ‘cultural colonization’?

You must think I’m talking nonsense again. But when I listen to Chanté Moore singing “If I Ain’t Got You,” I find it too boring. I know her singing is “good,” but this “good” has nothing to do with me. If, for Chinese listeners, Chanté Moore’s “good” is the standard, then is that what we in the music industry should be working towards? Isn’t that funny? When you open QQ Music or NetEase Cloud Music, and it recommends these songs to you every day, won’t you be convinced to practice again?

Of course, I know Chanté Moore is in good shape, very relaxed. Actually all of the Chinese singers tonight were very nervous. Yang Chenglin (杨丞琳) was nervous, Na Ying was also nervous. Even a seemingly carefree band like Second Hand Rose, if you listened to the introduction of their song, [you’ll find] they were so nervous that Yao Lan, supposedly “China’s No.1 Guitarist”, was so nervous that he hit the wrong note. It was not even a fast-paced solo (…), how nervous could he be? When everyone’s so tense, the confidence of Chanté Moore and Faouzia is indeed something that East Asia can’t match. In East-Asian [entertainment] circles, represented by China/Japan/Korea, our different cultural habits, upbringing, and ethnic characteristics have made it so that we don’t possess these kinds of singing abilities, even including our ways of emotional expression. I don’t know from which season it started with ‘Singer’ – and if it’s some kind of Catfish Effect (鲶鱼效应 ) – that they brought international singers with different cultural backgrounds into the competition. But this isn’t the Olympics, it’s not like Liu Xiang [刘翔, Chinese gold medal hurdler] is going to defeat opponents from the United States or Cuba. “I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like Alicia Keys.” (This line is not mine, I stole it from my WeChat friend).

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Anyway, no matter if they’re strong or not, I would never vote for the foreigner.

The comment about ‘I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like [listening to] Alicia Keys’ refers to the craze surrounding China’s ‘BBQ town’ Zibo. In Zibo, Chinese visitors like to sing, drink beer, and enjoy food together; it’s a simple and modest way of appreciating life and music, which contrasts with slick and smooth American or foreign styles of performing and singing.

Whether Zou’s criticism was for attention or genuine sentiment, it shifted the focus of the discussion from music to patriotism.

CHINESE SINGERS WITH MILITARISTIC UNDERTONES

“I volunteer to join the battle”

Amidst all this, some netizens, easily swayed by nationalist sentiments, began to seek help from the “national team” (国家队) of singers — musicians employed by national-level arts troupes — to “bring glory to the nation” and teach the foreigners a lesson. Some even questioned the intentions of the Singer 2024 TV show in inviting foreign singers to participate.

On May 12th, renowned Chinese singer and philanthropist Han Hong (韩红) posted on Weibo, fueling a wave of sentiment and support. In her post, Han Hong declared, “I am Chinese singer Han Hong, and I volunteer to join the battle,” tagging the production team of the TV show. Her invitation to join the battle quickly went viral.

Han Hong meme: “Who called for me?”

Han Hong has significant influence in the Chinese music industry and society as a whole. Her usual serious demeanor and avoidance of internet pop culture made netizens unsure whether she was joking or serious. Nevertheless, regardless of her intentions, a group of well-known singers began to volunteer via Weibo, emphasizing their identity as “Chinese singers” and using phrases with strong militaristic undertones like “fighting for the country” and “answering the call.”

Although many enjoyed this new wave of national pride in Chinese music and performers, some netizens criticized the trend of transforming an entertainment show into a nationalistic competition.

Film critic He Xiaoqin (何小沁) stated, “It’s okay to take the Qing-Dynasty-fighting-foreigners comparison as a joke, but taking it too seriously in today’s context is absurd.”

Others expressed fatigue with how quickly topics on Chinese internet platforms escalate to patriotic sentiments. To bring the focus back to entertainment, they turned “I volunteer to join the battle” (#我请战#) into a new internet catchphrase.

In response, the production team of Singer 2024 released a statement on Weibo, thanking all the singers for their self-recommendations. They emphasized the show’s competitive structure but clarified that “winning” is just one part of a singer’s journey..but that the love of music goes beyond all in connecting people, no matter where they’re from.

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Online reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among Chinese netizens.

Published

3 months agoon

April 18, 2024

The recent marriage announcement of the renowned Chinese calligrapher/painter Fan Zeng and Xu Meng, a Beijing TV presenter 50 years his junior, has sparked online discussions about the life and work of the esteemed Chinese artist. Some netizens think Fan lacks the integrity expected of a Chinese scholar-artist.

Recently, the marriage of a 86-year-old Chinese painter to his bride, who is half a century younger, has stirred conversations on Chinese social media.

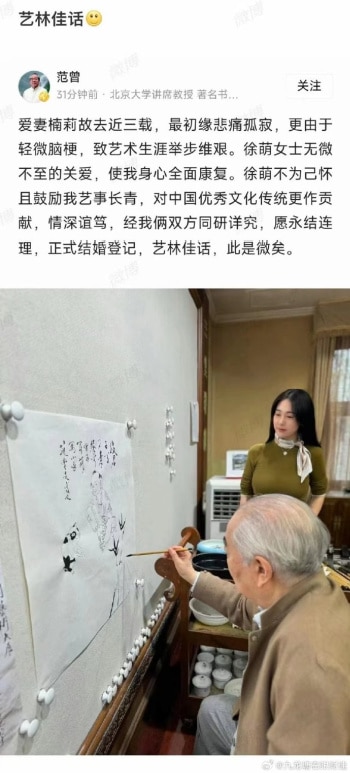

The story revolves around renowned Chinese artist, calligrapher, and scholar Fan Zeng (范曾, 1938) and his new spouse, Xu Meng (徐萌, 1988). On April 10, Fan announced their marriage through an online post accompanied by a picture.

In the picture, Fan is seen working on his announcement in calligraphic form.

Fan Zeng announces his marriage on Chinese social media.

In his writing, Zeng shares that the passing of his late wife, three years ago, left him heartbroken, and a minor stroke also hindered his work. He expresses gratitude for Xu Meng’s care, which he says led to his physical and mental recovery. Zeng concludes by expressing hope for “everlasting harmony” in their marriage.

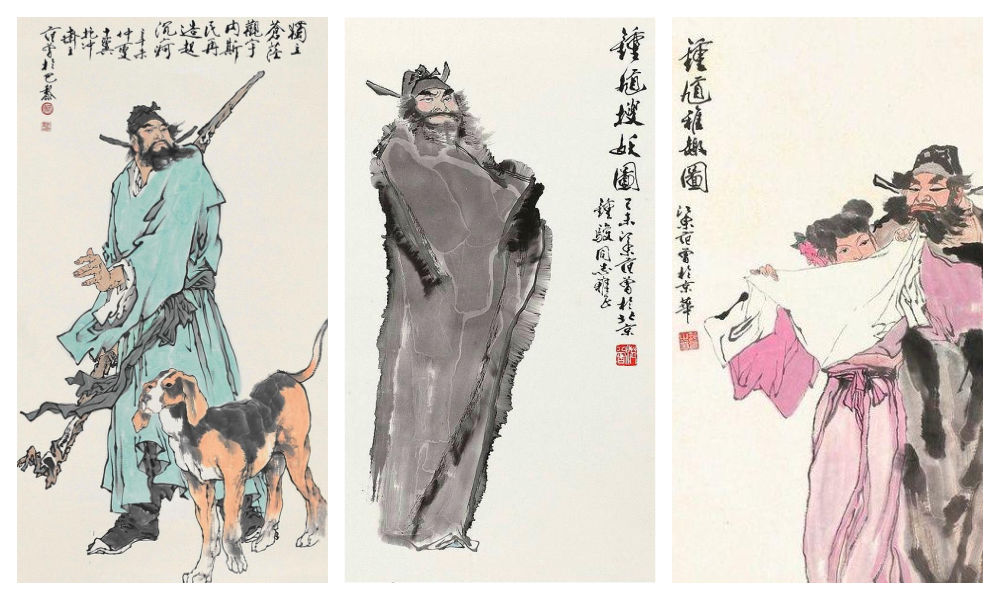

Fan Zeng is a calligrapher and poet, but he is primarily recognized as a contemporary master of traditional Chinese painting. Growing up in a well-known literary family, his journey in art began at a young age. Fan studied under renowned mentors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, including Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Jiang Zhaohe, and Li Kuchan.

Fan gained global acclaim for his simple yet vibrant painting style. He resided in France, showcased his work in numerous exhibitions worldwide, and his pieces were auctioned at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the 1980s.[1] One of Fan’s works, depicting spirit guardian Zhong Kui (钟馗), was sold for over 6 million yuan (828,000 USD).

Zhong Kui in works by Fan Zeng.

In his later years, Fan Zeng transitioned to academia, serving as a lecturer at Nankai University in Tianjin. At the age of 63, he assumed the role of head of the Nankai University Museum of Antiquities, as well as holding various other positions from doctoral supervisor to honorary dean.

By now, Fan’s work has already become part of China’s twentieth-century art history. Renowned contemporary scholar Qian Zhongshu once remarked that Fan “excelled all in artistic quality, painting people beyond mere physicality.”

A questionable “role model”

Fan’s third wife passed away in 2021. Later, he got to know Xu Meng, a presenter at China Traffic Broadcasting. Allegedly, shortly after they met, he gifted her a Ferrari, sparking the beginning of their relationship.

A photo of Xu and her Hermes Birkin 25 bag has also been making the rounds on social media, fueling rumors that she is only in it for the money (the bag costs more than 180,000 yuan / nearly 25,000 USD).

On Weibo, reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among netizens. Despite Fan’s reputation as a prominent philanthropist, many perceive his recent marriage as yet another instance of his lack of integrity and shamelessness.

Fan Zeng and Xu Meng. Image via Weibo.

One popular blogger (@好时代见证记录者) sarcastically wrote:

“Warm congratulations to the 86-year-old renowned contemporary erudite scholar and famous calligrapher Fan Zeng, born in 1938, on his marriage to Ms Xu Meng, a 50 years younger 175cm tall woman who is claimed to be China’s number one golden ratio beauty. Mr Fan Zeng really is a role model for us middle-aged greasy men, as it makes us feel much less uncomfortable when we’re pursuing post-90s youngsters as girlfriends and gives us an extra shield! Because if contemporary Confucian scholars [like yourself] are doing this, then we, as the inheritors of Confucian culture, can surely do the same!“

Various people criticize the fact that Xu Meng is essentially just an aide to Fan, as she can often be seen helping him during his work. One commenter wrote: “Couldn’t he have just hired an assistant? There’s no need to turn them into a bed partner.”

Others think it’s strange for a supposedly scholarly man to be so superficial: “He just wants her for her body. And she just wants him for his inheritance.”

“It’s so inappropriate,” others wrote, labeling Fan as “an old bull grazing on young grass” (lǎoniú chī nèncǎo 老牛吃嫩草).

Fan is not the only well-known Chinese scholar to ‘graze on young grass.’ The famous Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), now 101 years old, also shares a 48-year age gap with his wife Weng Fen (翁帆). Fan, who is a friend of Yang’s, previously praised the love between Yang and Weng, suggesting that she kept him youthful.

Older photo posted on social media, showing Fan attending the wedding ceremony of Yang Zhenning and his 48-year-younger partner Weng Fen.

Some speculate that Fan took inspiration from Yang in marrying a significantly younger woman. Others view him as hypocritical, given his expressions of heartbreak over his previous wife’s passing, and how there’s only one true love in his lifetime, only to remarry a few years later.

Many commenters argue that Fan Zeng’s conduct doesn’t align with that of a “true Confucian scholar,” suggesting that he’s undeserving of the praise he receives.

“Mr. Wang from next door”

In online discussions surrounding Fan Zeng’s recent marriage, more reasons emerge as to why people dislike him.

Many netizens perceive him as more of a money-driven businessman rather than an idealistic artist. They label him as arrogant, critique his work, and question why his pieces sell for so much money. Some even allege that the only reason he created a calligraphy painting of his marriage announcement is to profit from it.

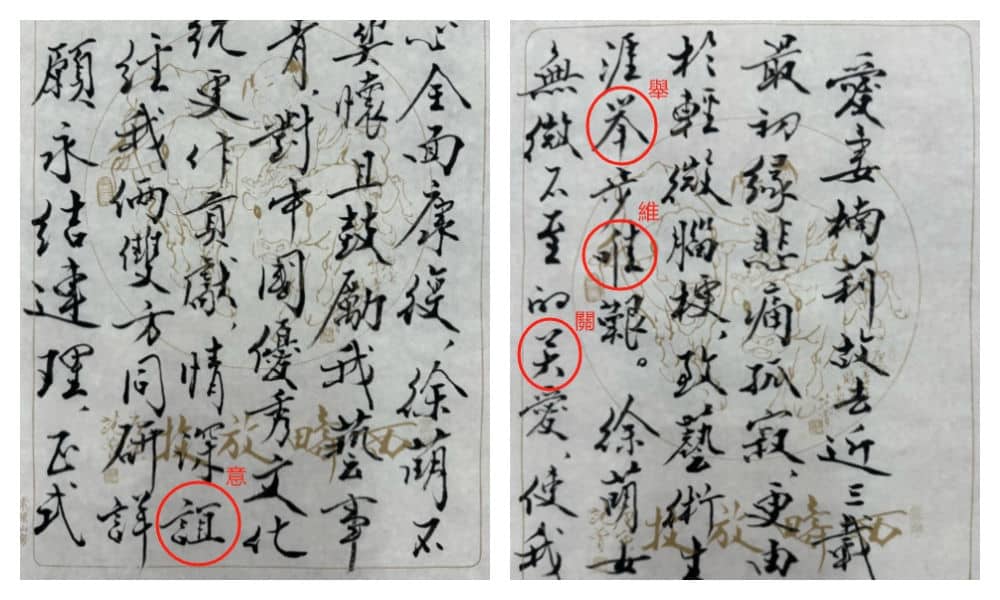

Others cast doubt on his status as a Chinese calligraphy ‘grandmaster,’ noting that his calligraphy style is not particularly impressive and may contain typos or errors. His wedding announcement calligraphy appears to blend traditional and simplified characters.

Netizens have pointed out what looks like errors or typos in Fan’s calligraphy.

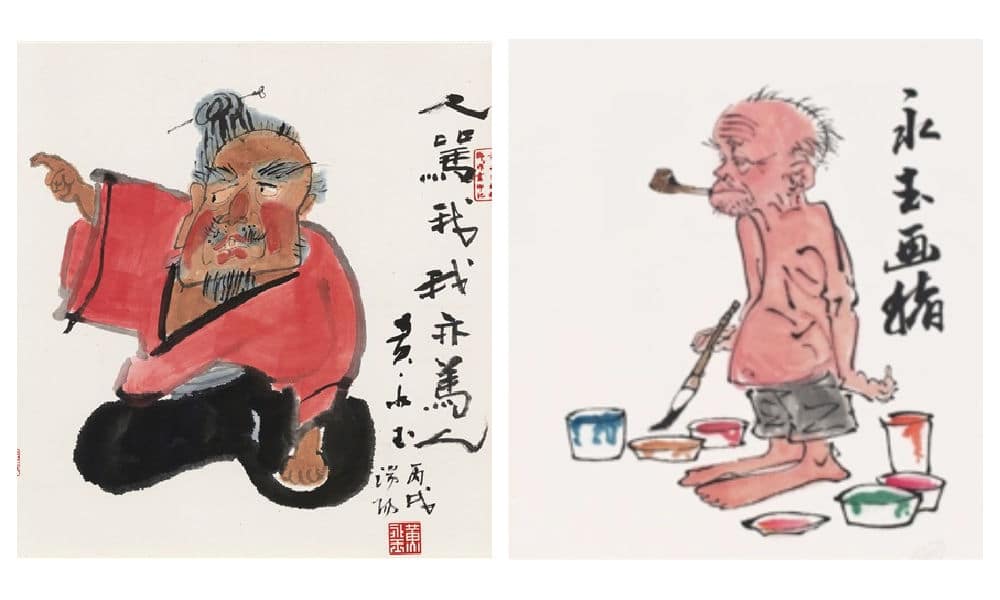

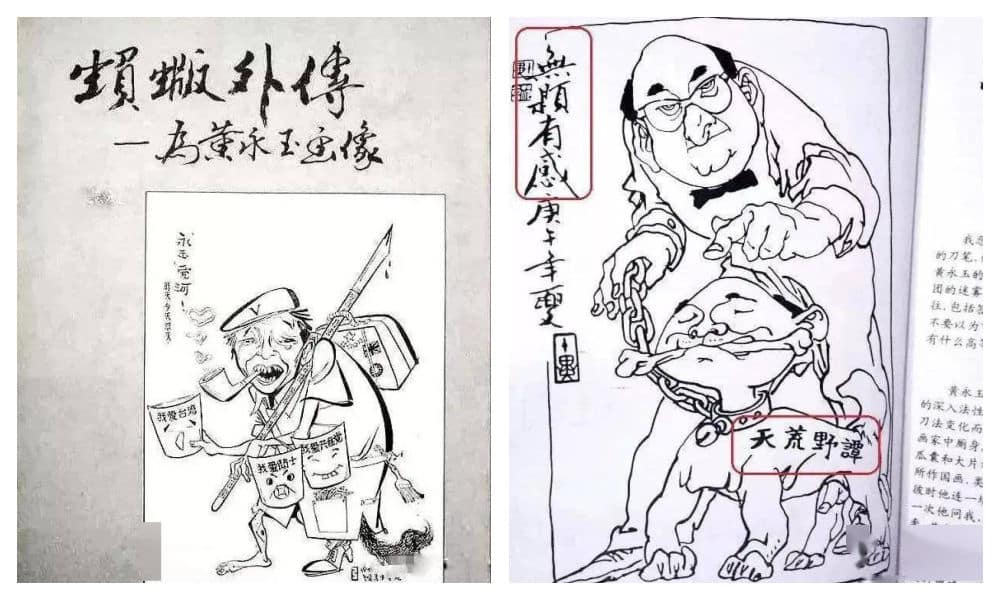

Another source of dislike stems from his history of disloyalty and his feud with another prominent Chinese painter, Huang Yongyu (黄永玉). Huang, who passed away in 2023, targeted Fan Zeng in some of his satirical paintings, including one titled “When Others Curse Me, I Also Curse Others” (“人骂我,我亦骂人”). He also painted a parrot, meant to mock Fan Zeng’s unoriginality.

Huang Yongyu made various works targeting Fan Zeng.

In retaliation, Fan produced his own works mocking Huang, sparking an infamous rivalry in the Chinese art world. The two allegedly almost had a physical fight when they ran into each other at the Beijing Hotel.

Fan Zeng mocked Huang Yongyu in some of his works.

Fan and Huang were once on good terms though, with Fan studying under Huang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Through Huang, Fan was introduced to the renowned Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文, 1902-1988), Huang’s first cousin and lifelong friend. As Shen guided Fan in his studies and connected him with influential figures in China’s cultural circles, their relationship flourished.

However, during the Cultural Revolution, when Shen was accused of being a ‘reactionary,’ Fan Zeng turned against him, even going as far as creating big-character posters to criticize his former mentor.[2] This betrayal not only severed the bond between Shen and Fan but also ended Fan’s friendship with Huang, and it is still remembered by people today.

Fan Zeng’s behavior towards another former mentor, the renowned painter Li Kuchan (李苦禪, 1899-1983), was also controversial. Once Fan gained fame, he made it clear that he no longer respected Li as his teacher. Li later referred to Fan as “a wolf in sheep’s clothes,” and apparently never forgave him. Although the exact details of their falling out remain unclear, some blame Fan for exploiting Li to further his own career.

There are also some online commenters who call Fan Zeng a “Mr Wang from next door” (隔壁老王), a term jokingly used to refer to the untrustworthy neighbor who sleeps with one’s wife. This is mostly because of the history of how Fan Zeng met his third wife.

Fan’s first wife was the Chinese female calligrapher Lin Xiu (林岫), who came from a wealthy family. During this marriage, Fan did not have to worry about money and focused on his artistic endeavours. The two had a son, but the marriage ended in divorce after a decade. Fan’s second wife was fellow painter Bian Biaohua (边宝华), with whom he had a daughter. It seems that Bian loved Fan much more than he loved her.

It is how he met his third wife that remains controversial to this day. Nan Li (楠莉), formerly named Zhang Guiyun (张桂云), was married to performer Xu Zunde (须遵德). Xu was a close friend of Fan, and helped him out when Fan was still poor and trying to get by while living in Beijing’s old city center.

Wanting to support Fan’s artistic talent, Xu let Fan Zeng stay over, supported him financially, and would invite him for meals. Little did he know that while Xu was away to work, Fan enjoyed much more than meals alone; Fan and Xu’s wife engaged in a secret decade-long affair.

When the affair was finally exposed, Xu Zunde divorced his wife. Still, they would use his house to meet and often locked him out. Three years later, Nan Li officially married Fan Zeng. Xu not only lost his wife and friend but also ended up finding his house emptied, his two sons now bearing Fan’s surname.

When Nan Li passed away in 2021, Fan Zeng published an obituary that garnered criticism. Some felt that the entire text was actually more about praising himself than focusing on the life and character of his late wife, with whom he had been married for forty years.

Fan Zeng and his four wives

An ‘old pervert’, a ‘traitor’, a ‘disgrace’—there are a lot of opinions circulating about Fan that have come up this week.

Despite the negativity, a handful of individuals maintain a positive outlook. A former colleague of Xu Meng writes: “If they genuinely like each other, age shouldn’t matter. Here’s to wishing them a joyful marriage.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Song, Yuwu. 2014. Biographical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China. United Kingdom: McFarland & Company, 76.

[2]Xu, Jilin. 2024. “Xu Jilin: Are Shen Congwen’s Tears Related to Fan Zeng?” 许纪霖:沈从文的泪与范曾有关系吗? The Paper, April 15. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_27011031. Accessed April 17, 2024.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions