China Health & Science

How Could a Cancer Patient’s ‘Crazy Shopping Spree’ Become the Subject of Ridicule on Weibo?

A trending story about a rich woman allegedly spending $600,000 during a shopping spree in a Sichuan mall has taken an unexpected turn.

Published

8 years agoon

A story that went trending on Chinese social media this week about a rich woman spending $600,000 during a shopping expedition in a Sichuan mall has taken an unexpected turn. Family members have stepped forward to deny the rumors, and say the woman is suffering from brain cancer. She went missing after photos of her shopping spree went viral.

A young woman from Sichuan caught the attention of netizens on Weibo this week when images emerged of her extravagant shopping spree. Some people on Chinese social media alleged the woman had spent at least 4 million yuan (±600,000$) in one day.

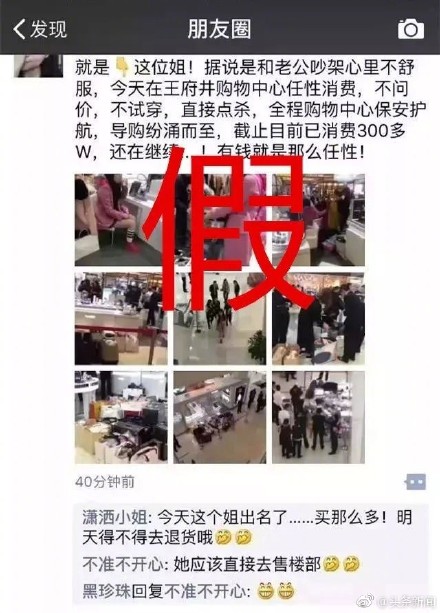

The photos and videos, taken by bystanders, show the woman’s growing pile of shopping bags at the Wangfujing Shopping Mall in Chengdu on Sunday night. Dressed in a pink coat, the woman can be seen purchasing various items while being assisted by a group of employees at the mall’s boutique brand stores.

The woman was ridiculed on Weibo when she attracted the attention of netizens during her shopping spree.

She was called the “pink lady” on Weibo, with some saying: “We’ll never understand the tuhao.” Tuhao (土豪) is a popular word to describe China’s ‘uncultured’ nouveau riche.

Some netizens suggested that the woman was from a rich family and purposely spent large amounts of money to take revenge on her husband after having an argument. The story was spread on social media with the hashtag: “Woman spends thousands of dollars after fighting with husband” #女子和老公吵架商场狂刷上百万#).

“They do not care about the fight, they do not care about the frantic shopping, they just care about the thought that money is the answer to anything.”

After rumors of the woman’s shopping spree made their rounds on Weibo on October 23, family members of the woman came forward, saying that the woman was recently diagnosed with brain cancer and that she has gone missing since Monday. They told Chinese media that they fear she might be suicidal.

Family members also dispelled the trending rumors about the woman and the alleged extravagant amount of money she spent. They say her bank records show that she only spent 50.000 yuan (±7530$), rather than the alleged 4 million yuan.

FAKE NEWS: rumors about the woman were dispelled earlier this week.

The truth behind the trending topic shocked many commenters. “How could the ‘crazy shopping spree’ of a cancer patient be ridiculed by the masses?”, one Chinese blogger wondered.

“This is not the first time these kinds of carelessly fabricated and exaggerated rumors make it on social media, and it won’t be the last time,” the Weibo blogger nicknamed ‘Listen Up’ (@青听我说) writes.

‘Listen Up’ argues that the masses, craving for material wealth, are so obsessed with the extravagant behavior of China’s ‘crazy rich’ that they will feverishly make up any “fake news” when the facts are lacking:

“The majority of onlookers really don’t care about the reasons behind the ‘crazy shopping spree’ or about the true amount of money spent. From their point of view, the more they exaggerate the story and the bigger the amount of money, the more excited they get.”

“At the same time, it is also about self-pity. It is about ‘look at her, she can max out her credit card when she’s having trouble at home, while I would have to return to my parents in my hometown.'”

The writer notes that there is a powerful mass hysteria bubble when it comes to news about China’s rich; people do not care that this woman might have had a fight, they do not even care about her frantic shopping, they just care about the thought that money is the answer to anything.

“A woman, who was just diagnosed with cancer, is distraught and goes shopping. Even if her spending 50,000 yuan might go against logic, it is something to understand and to sympathize with. In this case, it is the onlookers who have to be ashamed of themselves.”

“In the eyes of the masses, everything has become ‘entertainment’ now. Too often, they do not look at the facts, they do not question the what & how, and they do not investigate the outcome. They just want to satisfy a temporary crave for some excitement, and it doesn’t matter what it is. This is not just harmful to the persons involved and who become the target of ridicule, it is also harmful to yourself because eventually, it is really your own life that is becoming ridiculous.”

“Money has become the sole criterion by which they judge the world.“

Writer Zeng Li recently noted on sixthtone.com that for many Chinese, “money has become the sole criterion by which they judge the world.”

As Chinese economy is growing, so is the gap between social classes. According to Zeng Li, a so-called ‘chain of contempt’ (鄙视链) is at work in Chinese society, where – like a food chain – there is a hierarchy of social layers where certain groups of people always look down on the other. On top of the chain are China’s rich and successful people.

But on Chinese social media, it is apparent that China’s ‘tuhao‘ or ‘filthy rich’ are also frequently mocked and despised, even if it might come with some sense of envy and self-pity as suggested by the ‘Listen Up’ blogger.

Some of the crazy rich stories that go trending online are a source of much hilarity, like a fancy tuhao car that gets stuck in the mud of a rural area – literally becoming a ‘filthy rich’ car.

This tuhao’s fancy car got stuck in the mud.

But people seem to be so hungry for “crazy rich” stories that they easily add to the hysteria by making up facts – soon turning one event into a completely different story.

“She’s gone missing because of you.”

It is unsure if the woman, whose identity has not been revealed, has been found yet. According to insiders, before her disappearance, the woman was informed that her shopping spree had gone viral on Weibo and WeChat and was very unhappy about it.

On Weibo, many netizens now express their anger over the situation: “She just spent some money, so what? Now she’s gone missing because of you – the internet is a bad place,” some netizens write.

“Even if she had spent in fact 4 million yuan, then what’s it to you?,” another person commented: “She just spent 50,000 yuan and you all stand in a circle, watch her, and take pictures. Would you take pictures of other people spending money?”

Despite the support for the woman, there are also many people who are still wondering if she did in fact spent 50,000 yuan or more.

“What’s wrong with you people?”, some answer: “The only thing that matters is that she returns home safely.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Animals

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

“We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

Published

2 months agoon

October 5, 2025

China is facing a serious donkey shortage. China’s donkey population is far below market demand, and the prices of donkey-related products continue to rise.

Recently, this issue went trending on Weibo under hashtags such as “China Currently Faces a Donkey Crisis” (#我国正面临缺驴危机#).

The Donkey Branch of China’s Livestock Association (中国畜牧业协会驴业分会) addressed this issue in Chinese media earlier last week, telling China News Weekly (中国新闻周刊): “We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

China’s donkey population has plummeted by nearly 90% over the past decades, from 11.2 million in 1990 to just 1.46 million in 2023.

The massive drop is related to the modernization of China’s agricultural industry, in which the traditional role of donkeys as farming helpers — “tractors” — has diminished. As agricultural machines took over, donkeys lost their role in Chinese villages and were “laid off.”

Donkeys also reproduce slowly, and breeding them is less profitable than pigs or sheep, partly due to their small body size.

Since 2008, Africa has surpassed Asia as the world’s largest donkey-producing region. Over the years, China has increasingly relied on imports to meet its demand for donkey products, with only about 20–30% of the donkey meat on the market coming from domestic sources.

China’s demand for donkeys mostly consists of meat and hides. As for the meat — donkey meat is both popular and culturally relevant in China, especially in northern provinces, where you’ll find many donkey meat dishes, from burgers to soups to donkey meat hotpot (驴肉火锅).

However, the main driver of donkey demand is the need for hides used to produce Ejiao (阿胶) — a traditional Chinese medicine made by stewing and concentrating donkey skin. Demand for Ejiao has surged in recent years, fueling a booming industry.

China’s dwindling donkey population has contributed to widespread overhunting and illegal killings across Africa. In response, the African Union imposed a 15-year ban on donkey skin exports in February 2023 to protect the continent’s remaining donkey population.

As a result of China’s ongoing “donkey crisis,” you’ll see increased prices for donkey hides and Ejiao products, and oh, those “donkey meat burgers” you order in China might actually be horse meat nowadays. Many vendors have switched — some secretly so (although that is officially illegal).

Efforts are underway to reverse the trend, including breeding incentives in Gansu and large-scale farms in Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang.

China is also cooperating with Pakistan, one of the world’s top donkey-producing nations, and will invest $37 million in donkey breeding.

However, experts say the shortage is unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

The quote that was featured by China News Weekly — “We have cows and horses, but no donkeys” (“牛马有的是,就缺驴”) — has sparked viral discussion online, not just because of the actual crisis but also due to some wordplay in Chinese, with “cows and horses” (“牛马”) often referring to hardworking, obedient workers, while “donkey” (“驴”) is used to describe more stubborn and less willing-to-comply individuals.

Not only is this quote making the shortage a metaphor for modern workplace dynamics in China, it also reflects on the state media editor who dared to feature this as the main header for the article. One Weibo user wrote: “It’s easy to be a cow or a horse. But being a donkey takes courage.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Health & Science

Breaking the Taboo: China’s Sanitary Pad Controversy Sparks Demand for Change

After realizing domestic sanitary pads were literally falling short, Chinese netizens are demanding greater awareness and improvements in long-overlooked issues of quality, affordability, and societal attitudes toward menstruation.

Published

1 year agoon

December 6, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Sanitary pads have never been a bigger topic of debate on Chinese social media as it’s been over the past few weeks. What began with one blogger’s discovery of menstrual pads falling short of their advertised size has grown into a broader movement, demanding better-quality products and greater awareness of menstrual health.

Despite being a natural part of life for women around the world, menstruation remains a sensitive and taboo subject in many parts of China, particularly in more conservative, rural areas and smaller cities.

Essential feminine hygiene products like sanitary pads or tampons are often discreetly wrapped in dark plastic bags to avoid drawing attention.

However, this month, the silence was broken. “Sanitary pads” and related topics dominated online discussions, igniting a heated conversation that started with pad length but quickly expanded to include concerns about health, safety, and women’s rights.

EXPOSING THE “SHORTCOMINGS” IN SANITARY PADS

“Buy it if you want, or just don’t.”

In early November, a viral post on Xiaohongshu (later deleted) brought attention to a troubling issue. A woman who purchased sanitary pads online found them significantly shorter than advertised—a supposed 290mm pad measured only 250mm.

When she confronted the seller, they dismissed her concerns, citing a “normal 4% margin of error” and claiming, “If you order 290mm, we can only send 250mm—that’s the rule.”

The post struck a nerve. Netizens began measuring their own pads and discovered that many brands similarly fell short of their advertised lengths. This perceived deception ignited widespread outrage:

“They market themselves as designed for women, but even the lengths are misleading?”

“We pay the highest taxes for subpar products!”

The controversy soon spread to platforms like Douban and Weibo, where more and more people started comparing advertised versus actual pad lengths. The results revealed that many well-known brands consistently fell short, raising accusations of industry-wide cost-cutting.

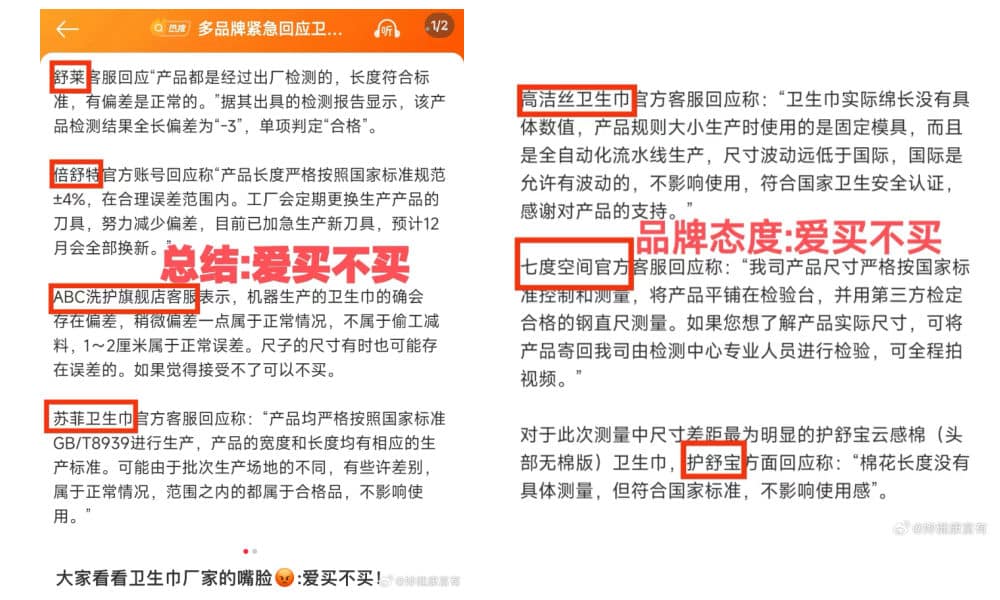

Facing mounting pressure, several Chinese brands issued responses claiming their products adhered to the national standard that allows a ±4% length deviation. According to this standard, a 290mm pad can legally measure between 278mm and 302mm.

However, consumer measurements consistently showed pads at the lower limit—or even shorter. This raised suspicions that manufacturers were exploiting the -4% allowance as an industry norm to cut costs.

Some netizens compiled a crowdsourced chart comparing the advertised length, actual length, and cotton coverage of various brands. The findings revealed similar discrepancies across major brands.

Various brands’ responses to the controversy listed by blogger @妳健康富有.

Some brands, with size deviations as large as -15%, responded evasively to consumer concerns, claiming that such deviations are normal and do not affect usage. These responses only fueled further frustration among netizens, who accused the brands of dismissing their concerns. As one blogger (@你健康富有) remarked, the brands’ attitude couldn’t be clearer: “‘Buy it if you want, or just don’t.'”

BEYOND LENGTH: A DEEPER ISSUE

“Society tolerates or even reinforces menstrual stigma.”

While the pad length scandal initially focused on cost-cutting, the ensuing discussions uncovered far more serious concerns. A resurfaced video by documentary filmmaker and blogger Fourfire (四火, @为了玲飞护肤纪录片) revealed the industry’s dark side. The video exposed illegal factories recycling used materials, including shredded pads and diapers, into new sanitary products. These contaminated pads, sold cheaply on e-commerce platforms, have been linked to pelvic inflammation and other gynecological problems.

In the video, Fourfire urged women to stick to well-known brands and purchase from reputable retailers.

Still from the video by documentary filmmaker and blogger Fourfire (四火, @为了玲飞护肤纪录片)

But are pricier pads from major retailers truly safe? Quality issues with domestic brands have surfaced repeatedly, and this latest length discussion reignited those concerns. Consumer-created “red-flagged brands” for domestic pads feature numerous well-known brands with prior reports of containing maggots, mold, and other contaminants.

This renewed scrutiny prompted questions and discussions among female netizens. One user asked, “Is there any brand of sanitary pads that’s actually safe to use?” Among the hundreds of replies and shares, one prevailing sentiment emerged: “None of them.” Many users began to view previous quality issues not as isolated incidents but as indicative of broader problems within the industry.

Adding fuel to the fire, one blogger (@迷宝吃不饱) claimed that the national standards for sanitary pads in China allow a pH range of 4–9. This range aligns with standards for non-intimate textiles, such as jackets or curtains. Given that human skin is slightly acidic, with a pH between 4.1 and 5.8 (3.8–4.5 for intimate zones), products in close contact with the skin, such as sanitary pads, should ideally be designed to maintain the skin’s natural pH balance and prevent irritation.

This seemingly loose standard sparked further concerns among female consumers. Many began reflecting on their past experiences, sharing issues they’d faced while using sanitary pads—frequent inflammation, allergic reactions, itching, and other symptoms. Few had considered the possibility that these problems might be linked to the pads themselves.

In response, experts argued that the materials, hygiene, and sterilization of pads were far more critical than pH levels. However, in today’s China, where public trust in such authorities is relatively low (read: “Experts Are Advised Not to Advise“), this explanation not exactly reassured the public. Gynecologists and popular science influencers, such as Sixthfloor (@六层楼先生), pointed out that similar products like baby diapers and men’s sanitary pads are held to stricter production standards. This disparity naturally fueled suspicion and concern about women being disadvantaged and the role of societal taboos surrounding menstruation.

One Douban user commented: “Society tolerates or even reinforces menstrual stigma. The less we talk about sanitary pads, the easier it is for companies to profit from women.”

BREAKING THE SILENCE

“Decisions about menstrual products are being made by people who don’t menstruate.”

Sanitary pads in China are relatively expensive and not covered by health insurance. A single daytime pad from a common brand costs around 1 RMB ($0.15), while nighttime pads can be twice as expensive. Over a typical six-day period, a woman might spend 30-40 RMB ($4.15-$5.50) each month. Tampons, though less popular in China, are even more costly.

For women in impoverished or rural areas, this expense can be a significant burden. Many are forced to purchase low-cost, unregulated “three-no” products (no license, no standards, no brand), often manufactured by the shady companies exposed in Fourfire’s video. On Taobao, product reviews for these pads reveal heartbreaking stories. Some users recommend switching to safer, higher-quality options, but responses often reflect the harsh reality: “I don’t have a choice.”

Now, as major brands face public backlash, many women are turning to “medical-grade sanitary pads,” originally made for surgical recovery or heavy bleeding. According to the Sichuan Observation media channel (@四川观察), online searches for these products have jumped by over 3,000%. While safer, these pads are even more expensive.

The frustration is clear: “Do we really have to keep paying more for basic necessities just to protect our health? Why not just make regular sanitary pads safe and reliable? Is that too much to ask?”

So why is it so hard to produce affordable, safe sanitary pads without cost-cutting tricks? The answer may lie in a regulatory change made over a decade ago. In 2008, new national standards for sanitary pads eliminated quality grading classifications and reduced minimum requirements for the length of filling cotton. This gave manufacturers more freedom to cut costs, often at the expense of quality.

One glaring detail hasn’t gone unnoticed: the revised standards were drafted entirely by men. As one netizen commented, “Decisions about menstrual products are being made by people who don’t menstruate.” For women, the lack of female representation in an industry directly affecting them is both absurd and infuriating, highlighting a deeper issue of gender imbalance in industries and regulatory frameworks that shape women’s lives.

At the time of writing, distrust in domestic sanitary pad brands in China has reached a peak. Whether driven by exaggerated fears or valid concerns, one thing is clear: after years of menstrual stigma and neglect of women’s health issues, many women feel unheard and are now speaking out. This growing frustration has given rise to an online feminist movement, calling for accountability and demanding change from an industry—and a culture—that has long overlooked some of women’s basic rights.

GRASSROOTS EFFORTS FOR CHANGE

“Girls should never feel ashamed of their periods”

With policymakers mostly male, Chinese women have had to take matters into their own hands. Over the years, various incidents related to menstrual products have gone viral and triggered grassroots efforts to improve the status quo.

The last major public outcry about sanitary pads occurred in 2022 when a woman on a high-speed train discovered they weren’t available for purchase. She vented her frustration online, and the issue quickly gained traction. Many commenters, mostly men, argued that pads weren’t “essential items” and didn’t warrant taking up retail space onboard. The railway authority’s official response—categorizing sanitary pads as “personal items” that didn’t need to be sold—only intensified the outrage.

In the same year, a young woman in Covid quarantine in Xi’an went viral after she tearfully begged anti-epidemic staff for sanitary pads. When workers at her quarantine hotel told her there was nothing they could do, she asked, “So what? Does that mean I have to bleed a river of blood?”

For many women, these incidents highlighted how little society understands or respects their basic needs. In response, people organized online campaigns, flooded hotlines with complaints, and raised awareness about why menstrual products are essential. “Girls should never feel ashamed of their periods,” one netizen wrote.

Sometimes, progress is made. The woman in Xi’an’s quarantine later posted an update, saying she eventually received the menstrual pads she needed. And although pads are still not available on all high-speed trains, they are now provided on many routes—a small but meaningful step.

This time, the debate over pad quality has drawn even greater attention, involving public figures, celebrities, and even tech mogul and Xiaomi founder Lei Jun (雷军), with some hoping that a trusted brand like Xiaomi could play a role in making Chinese sanitary pads safer and more innovative. Women have launched cross-platform campaigns like #ShowYourSanitaryPads (#晒出你的卫生巾#), encouraging people to share posts on Weibo, Douban, and Xiaohongshu to call out brands for inaccurate sizing or poor quality.

Activists are also sharing step-by-step guides on filing formal complaints and advocating for stricter national production standards. The movement is gaining momentum, driven by a collective determination to demand safer, more reliable products.

On November 21, China News Weekly reported that a new national standard for sanitary pads is being drafted. CNR News also called for tighter industry oversight, signaling an urgent response to recent public criticism.

Yet, this response only scratches the surface of the deeper issues surrounding menstrual products in China. Challenges such as the high cost of pads, their limited availability in public spaces, and inadequate menstrual education persist. Will meaningful change continue to rely solely on grassroots efforts? Hopefully, this marks the beginning of a broader, systemic shift that not only addresses these immediate concerns but also redefines how society values and prioritizes women’s basic needs.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral5 months ago

China Memes & Viral5 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital11 months ago

China Digital11 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained