Chinese Signals

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

From top trends to platform scandals, these were the biggest online topics of the year.

Published

2 months agoon

Entering 2026, let’s take this time to reflect on a year of social media in China and the most noteworthy trending stories.

This is a list of major controversies & online moments that not only went completely viral but were also intrinsically connected to China’s social media sphere, either because they blew up on Weibo, originated on Douyin, or would not have even come to light if it weren’t for Xiaohongshu or other Chinese apps.

This is my pick of the top 10 topics and discussions that stood out most this year, capturing the broader sentiments shaping China’s social media landscape in 2025.

(PS: The items on this list are numbered chronologically and are not indicative of the importance/weight of the story.)

10. The ‘TikTok Refugee’-Xiaohongshu Honeymoon

At the beginning of 2025, a rare moment unfolded on Chinese social media. As American TikTok users faced a looming U.S. ban, they migrated to the Chinese app Xiaohongshu. This massive influx of so-called “TikTok refugees” (TikTok 难民) unexpectedly propelled Xiaohongshu to the number-one spot in app stores across the U.S. and beyond.

While the movement initially began as a tongue-in-cheek protest mocking U.S. authorities’ panic over Chinese companies stealing data, it soon turned into a genuine moment of cultural connection, as international users began building real relationships with the Chinese community on a fully domestic platform—sharing recipes, discussing culture, and practicing language.

Amid geopolitical tensions and a desire for cultural exchange, the fictional character ‘Li Hua’ unexpectedly emerged as a bridge between Chinese and American netizens. Li Hua (李华) is a familiar figure in China’s English writing exams, often used as a ‘stand-in’ for students to write letters to an imaginary foreign friend. Chinese users began digging up old exam papers and sharing the letters they had written years ago, often with captions like “Why didn’t you reply?” as a playful suggestion that Chinese students had been reaching out to foreign friends for years without ever hearing back.

Then, something extraordinary happened: Americans started replying to Li Hua. Posts appeared addressed to the fictional character, with messages like, “Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry the world kept us apart.”

These exchanges came to symbolize the distance that has long separated Chinese and American people. For many, this ‘Xiaohongshu moment’ underscored how anti-Chinese and anti-American sentiments have shaped narratives for years, fostering mutual misunderstanding. At the same time, the moment demonstrated not only the growing reach of Chinese-made platforms, but more importantly the power of online spaces to reshape relationships & create moments of unity amid a widening digital and geopolitical divide.

9. The China Tour of American Livestreamer IShowSpeed

Before March of 2025, many people in China had never heard of American livestreamer IShowSpeed. In the United States, many followers of the online celebrity, whose real name is Darren Jason Watkins Jr, knew little about China. That all changed when the YouTuber, who already had over 34 million followers at the time, toured across China and did a total of eight livestreams, filming over 43 hours of footage from, among others, Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, and Chongqing.

IShowspeed’s China tour was an important media moment for several reasons. In China, where the 20-year-old IShowSpeed is known as Jiǎkànggē (甲亢哥) or ‘Hyperthyroid Bro’ for overdrive being his modus operandi, his tour was seen as a huge win for China’s foreign-facing propaganda and cultural diplomacy. Watkins’ livestreams became an ultimate representation of the Chinese cultural promotion playbook, featuring traditional opera, pandas, Kung-fu, the Great Wall, and traditional medicine alongside futuristic cities, high-speed rail, dancing robots and stunning drone shows.

Outside of China, the streams filled with cultural highlights mixed with cutting-edge technology were also embraced by fans who loved seeing the encounter of a young modern American with old traditional China, and appreciated how his energetic livestreams showed an entirely different side of China than that usually highlighted in American mainstream media. The tour attracted millions of new subscribers, and boosted Watkins’ brand and global fame.

What his visit showed is that China has entered a phase in which it is becoming more skilled at letting others help tell its story in ways that resonate with a young, global, online audience, with more livestreamers and influencers now following in his footsteps through similar trips and China-focused promotions. Even if the government did not pay the YouTuber directly (as his team emphasized), the trip was clearly coordinated and fit seamlessly into China’s broader soft power strategy.

8. The Mysterious Death of Internet Celebrity Cat Wukong

Wukong became one of China’s most beloved internet celebrity cats after Douyin bikepacking vlogger Zhao Shuo (赵朔) met the stray while camping during his journey across China (video). Cold and hungry, the cat meowed outside Zhao’s tent until he let her warm up inside his sleeping bag.

Zhao named her “Wukong,” after the Monkey King from Journey to the West, and took her along on his travels through western China, winning over millions of netizens in the process.

The happy story took a dark turn in April of 2025 in Ruoqiang County, Xinjiang, when Wukong suddenly went missing from the campsite. Using her GPS collar, Zhao found her lifeless body beside a highway just two hours later. Veterinarians found no signs of trauma, ruling out a vehicle collision or accident, while GPS data suggested the cat had been moved unusually far in a short time, raising unanswered questions about what had happened.

As Zhao searched for answers, local authorities became involved. Soon after, Zhao suddenly released a video apologizing for the “negative impact” of the incident and said he would stop pursuing the matter. Online mourning over Wukong quickly turned into backlash, with many netizens accusing local officials of pressuring Zhao into an apology and prioritizing narrative control over transparency.

As the story was muted, tributes to Wukong spread across China in the form of graffiti, artwork, and memorial posts (see here). For many, Wukong became more than an internet cat: her story became a symbol of ordinary citizens searching for truth in the face of official silence. Beyond representing the limits of speaking out online, this story was above all else about the special and moving bond between a man and his cat friend.

7. The Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal of the Year

Many things came together in late April of 2025 when a letter written by the legal wife of the renowned Beijing surgeon Xiao Fei (肖飞) at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital was widely circulated from WeChat to Weibo, Zhihu, and beyond.

In the letter, addressed to the hospital’s Disciplinary Committee, the wife exposed her husband’s serious violations of professional ethics and his extramarital affairs with, among others, a head nurse and the young resident physician Dong Xiying (董袭莹). Most shockingly, she provided evidence that Xiao had left a patient on the operating table for 40 minutes during a surgery due to a dispute involving his mistress.

As the hospital verified the claims, Xiao’s employment was terminated and he was expelled from the Communist Party, briefly becoming one of the most hated figures on the Chinese internet. Public attention then shifted toward Dong Xiying and her suspicious academic rise. Netizens questioned how she managed to transition from an economics degree to becoming a “model student” at the prestigious Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) in just a few years.

The scandal intensified when PUMC, which had previously promoted Dong as a success story, suddenly deleted articles about her and edited her name out of official commencement addresses.

The entire story caused something of an earthquake—not just within medical circles, but also in academic ones and across the internet at large, where netizens were particularly concerned about the broader social issues this story touched on: from fairness in education and corruption in academia to medical negligence and moral integrity.

6. The Labubu Craze & Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Known and loved by tweens, teens, and (female) Gen Z consumers all over the world, Labubu became the hottest toy and fashion accessory of 2025—as well as a breakthrough success for the Chinese designer toy market at large.

Labubu is a Gremlin-like character created by renowned Hong Kong-born artist Kasing Lung (龍家昇), whose work is inspired by Nordic legends of elves. Although Labubu has been around since 2015, it wasn’t until it became part of Chinese pop culture store POP MART’s toy lineup in 2019 that it began reaching a mass audience.

And so, the story of Labubu’s success is just as much the story of the success of POP MART and that of other Chinese companies following a similar journey by covering the entire chain of trendy toys, from product development to retail and marketing. From Labubu to other dolls such as Wakuku and Baby Three (BB3), these brands managed to hit such a cultural and commercial sweet spot over the past year.

Following the global popularity of the Chinese game Black Myth: Wukong and with China’s animation hit Ne Zha 2 hitting cinemas across the world, Labubu is lauded as another example of a successful Chinese cultural export, with experts calling it ‘a benchmark for China’s pop culture’ and viewing its success as a sign of the globalization of Chinese designer toys.

5. The “Nanjing Sister Hong” Case That Shook People’s Worldview

Recently, I was talking to a group of young Chinese students in Wuhan, explaining the kind of trending topics I write about for What’s on Weibo / Eye on Digital China. I mentioned a few examples, and not all stories seemed to ring a bell, but when I said I also covered the “Nanjing Sister Hong” (南京红姐) case, every single one of them had a strong reaction—from squeaks to giggles to burying their faces in their hands. It’s clear that this is a story that not only became one of the most discussed viral topics of the year, but also one that has become part of China’s popular cultural memory, with references to the story popping up everywhere, from online memes to comedy shows and Halloween costumes.

The case centers on the 38-year-old Mr. Jiao, who posed as a woman on different Chinese dating apps. As the red-haired ‘Ahong,’ he hooked up with many men in his rented room, secretly recording these encounters and uploading all of the footage online. The scandal surfaced online in July of 2025.

The exact number of men Jiao met and filmed remains unknown. While authorities have dismissed the viral claim of over 1,600 men as exaggerated, dozens of videos spread widely online, showing Jiao engaging in various forms of sexual activity with different male partners from all walks of life, from married businessmen to fitness trainers and foreign exchange students. Some women who saw the videos recognized their own partners in them.

The story caused significant social shock; the fact that so many (married) men would be willing to hook up with a stranger online who arguably, yet obviously, wasn’t actually female shook people’s worldviews on multiple levels. Although this triggered many jokes, it also raised uncomfortable questions about how many of these men put their wives and romantic partners at risk because of these unprotected encounters.

Chinese commentators and bloggers therefore tied the case to women’s sexual health, but social media discussions around the case also touched on other issues such as privacy violations, gender identity, fluid sexuality, and marginalized communities.

4. The Maskpark Scandal That Couldn’t be Displayed

Back in 2020, an online sex crime scandal known as the “Nth Room” shook South Korea. It made global headlines after news revealed that dozens of women and underage girls had fallen victim to a network of cybersex trafficking and exploitation on Telegram.

In August 2025, the Chinese internet was hit by a similar storm. The discovery of a large-scale, anonymous Chinese-language community on the encrypted Telegram app revealed a vast network of sexual exploitation and voyeuristic content, leading many to label the case China’s own “Nth Room.”

The group, named “Maskpark,” had over 100,000 members and dozens of subchannels sharing voyeuristic footage: girls recorded with hidden cameras in bathrooms; videos leaked through private home surveillance; and women unknowingly filmed in hotels, hospitals, or on the subway. The group even had a specific term for members sharing footage of their own sisters, mothers, wives, or daughters: “offering tributes” (shàng gòng, 上供).

As Maskpark switched to private, frustration grew over the lack of official investigation into the matter. Another major issue fueling the anger was the censorship of “Maskpark Gate.” The story was kept off trending lists, and searching the hashtag on Weibo returned the message: “This topic content cannot be displayed.”

While online sleuths and victims tried to amplify their voices to force action, they instead saw their posts deleted. This left many wondering who is actually standing up for women’s safety, while others pointed out that the scandal reveals how advanced hidden camera technology has become, making this not just a women’s issue, but a national problem.

3. The Jiangyou Incident: From School Bullying to Public Protests

In August 2025, the city of Jiangyou in Sichuan became the scene of a rare, large-scale protest following public outrage over a severe bullying incident and how it was handled.

The bullying incident at the center of this story happened outside school premises, involving three girls between the ages of 13 and 15 who ganged up on a 14-year-old girl named Lai (赖). Footage of the assault, recorded by bystanders, began circulating widely on Chinese social media, sparking widespread outrage among concerned netizens and parents.

When authorities acted not only slowly but also leniently towards the bullies, public anger grew—especially because one of the bullies could be heard saying in the videos, “It’s not like I haven’t been taken in [to jail] before.” The incident sparked anger due to lenient laws for minors, the calculated moves by the brutal bullies, and the epidemic of school violence that has been ongoing in China for years, which many feel is being inadequately handled by local authorities.

The outrage in Jiangyou grew so large that it spilled from online to offline, with crowds gathering outside the municipal building. As the crowd grew, tensions escalated, leading to rare clashes between protesters and police, footage of which spread online before being censored.

The case showed that as the rising number of bullying cases continues to fuel public frustration nationwide, local anger will continue to intensify, especially if authorities fail to address and prevent school bullying. Most of all, it shows that while public protests rarely grow so big on Chinese social media, it only takes a spark to create a heated crowd.

2. The Jingdezhen “Chicken Chop Bro”

Andy Warhol’s famous “15 minutes of fame” phrase, coined around 1967, predicted that modern media & pop culture would eventually make everyone briefly famous. By now, we know there is truth to his words. While social media didn’t make everyone famous, it has proven that anyone could be, if only for a little while.

But Warhol perhaps couldn’t have predicted that the recipe for online fame in China’s 2025 isn’t about money, flashy fashion, or showbiz talent. Instead, it is about being down-to-earth and raw. One of the Chinese hot phrases of the year was “Real-Person Vibes” (huó rén gǎn, 活人感), describing people or stories that feel unpolished and unfiltered—something that has become increasingly precious in a year dominated by AI-generated content.

Around the National Day holiday, a seller of chicken chops in the town of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi became insta-famous. Not just because his chicken chops suited the tastes of locals, but mostly due to his pragmatic attitude and lively energy, along with his superspeed service and clear order of serving customers. He ran his little food stall like a serious operation, and people appreciated that.

Under the nickname “Chicken Chop Brother” (鸡排哥 jīpáigē), Li Junyong (李俊永) became an overnight viral sensation, so successful that local authorities had to implement crowd management for his stall.

While these kinds of successes aren’t always everlasting, their impacts are major. In a time when many are trying to replicate this viral formula, his story shows that for a moment to truly strike a chord with the masses, it needs to be real—and tasty, too.

1. The Kuaishou Livestream Controversy

On the night of December 22, 2025, users scrolling through livestreams on the popular short video app Kuaishou noticed something deeply disturbing: their screens suddenly filled with pornographic and violent content. Soon, millions of users scrolled into the same shocking footage. The chaos continued for approximately 90 minutes before Kuaishou—which has over 415 million daily active users, including many minors—eventually shut down its entire livestreaming function around 11:30 PM.

In a statement the following day, Kuaishou claimed the platform had fallen victim to an attack by “the underground and gray industries,” announcing that the incident had been reported to the police. The event is not just China’s worst platform-level catastrophe of the year; it is one of the most dramatic management failures in Chinese internet history, considering millions witnessed explicit content in real-time for an hour and a half.

The incident is indicative of Kuaishou’s failing security operations, particularly its slow response time and lack of emergency protocols. More significantly, it revealed the advanced techniques of the attackers. They used approximately 17,000 “zombie accounts” acquired through long-term “account farming” to exploit vulnerabilities and bypass reviews. They then pushed pre-recorded explicit files to livestream servers while simultaneously paralyzing Kuaishou’s banning system.

This serves as a massive wake-up call for both Chinese platforms and authorities. In what is already one of the most extensive & sophisticated internet censorship systems in the world, regulatory control and scrutiny will only further intensify in China’s online environment in the year to come.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Eye on Digital China/What’s on Weibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform resurfaces in Africa, a new winter hotspot, why Chinese elites ‘run’ to Tokyo, and more.

Published

3 months agoon

November 21, 2025

🌊 Signals — Week 47 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China, Signals highlights slower trends and online currents behind the daily scroll. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Different from the China Trend Watch (check the latest one here if you missed it), this edition, part of the new Signals series, is about the slower side of China’s social media: the recurring themes and underlying shifts that signal broader trends beyond the quick daily headlines. Together with the deeper dives, the three combined aim to give you clear updates and a fuller overview of what’s happening in China’s online conversations & digital spaces.

For the coming two weeks, I’ll be traveling from Beijing to Chongqing and beyond (more on that soon) so please bear with me if my posting frequency dips a little. I’ll be sure to pick it up again soon and will do my best to keep you updated along the way. In the meantime, if you know of a must-try hotpot in Chongqing, please do let me know.

In this newsletter: Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform in Angola, a new winter hotspot, discussions on what happens to your Wechat after you die, why Chinese elites rùn to Tokyo, and more. Let’s dive in.

- 💰 The richest woman in China, according to the latest list by Hurun Research Institute, is the “queen of pharmaceuticals” Zhong Huijuan (钟慧娟) who has accumulated 141 billion yuan (over 19 billion USD). Women account for over 22% of Chinese billionaires (those with more than 5 billion RMB), underscoring China’s globally leading position in producing wealthy female entrepreneurs.

- 🧩 What happens to your WeChat after you die? A user who registered for NetEase Music with a newly reassigned phone number unexpectedly gained access to the late singer Coco Lee’s (李玟) account, as the number had originally belonged to her. The incident has reignited debate over how digital accounts should be handled after death, prompting platforms like NetEase and Tencent to reconsider policies on long-inactive accounts and take stronger measures to protect them.

- 📱 Although millions of viewers swoon over micro-dramas with fantasy storylines where rich, powerful men win over the “girl next door” through money and status, Chinese regulators are now stepping in to curb exaggerated plots featuring the so-called “dominant CEO” (霸道总裁) archetype, signaling stricter oversight for the booming short drama market.

- ☕ A popular Beijing coffee chain calling itself “People’s Cafe” (人民咖啡馆), with its style and logo evoking nationalist visual nostalgia, has changed its name after facing criticism for building its brand – including pricey coffee and merchandise – on Mao era and state-media political connotations. The cafe is now ‘Yachao People’s Cafe’ (要潮人民咖啡馆).

- 👀 Parents were recently shocked to see erotic ads appear on the Chinese nursery rhymes and children’s learning app BabyBus (宝宝巴士), which is meant for kids ages 0–8. BabyBus has since apologized, but the incident has sparked discussions about how to keep children safe from such content.

- 🧧The 2026 holiday schedule has continued to be a big topic of conversation as it includes a 9-day long Spring Festival break (from February 15 to February 23), making it the longest Lunar New Year holiday on record. The move not only gives people more time for family reunions, but also gives a huge boost to the domestic travel industry.

Hasan Piker’s Chinese Tour & The US–China Content Honeymoon

Livestreamer Hasan Piker during his visit to Tiananmen Square flag-rising ceremony.

It’s not time for the end-of-year overviews just yet – but I’ll already say that 2025 was the US–China ‘honeymoon’ year for content creation. It’s when China became “cool,” appealing, and eye-grabbing for young Western social media users, particularly Americans. The recent China trip of the prominent American online streamer Hasan Piker fits into that context.

This left-wing political commentator also known as ‘HasanAbi’ (3 million followers on Twitch, recently profiled by the New York Times) arrived in China for a two-week trip on November 11.

Piker screenshot from the interview with CGTN, published on CGTN.

His visit has been controversial on English-language social media, especially because Piker, known for his criticism of America (which he calls imperialist), has been overly praising China: calling himself “full Chinese,” waving the Chinese flag, joining state media outlet CGTN for an interview on China and the US, and gloating over a first-edition copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao (the Little Red Book). He portrays China as heavily misrepresented in the West and as a country the United States should learn from.

Hasan Piker did an interview with CGTN, posing with Li Jingjing 李菁菁.

During his livestreaming tour, Hasan, who is nicknamed “lemonbro” (柠檬哥) by Chinese netizens, also joined Chinese platforms Bilibili and Xiaohongshu.

But despite all the talk about Piker in the American online media sphere, online conversations, clicks, and views within China are underwhelming. As of now, he has around 24,000 followers on Bilibili, and he’s barely a topic of conversation on mainstream feeds.

Piker’s visit stands in stark contrast to that of American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins), who toured China in March. With lengthy livestreams from Beijing to Chongqing, his popularity exploded in China, where he came to be seen by many as a representative of cultural diplomacy.

IShowspeed in China, March 2025.

IShowSpeed’s success followed another peak moment in online US–China cultural exchange. In January 2025, waves of foreign TikTok users and popular creators migrated to the Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu amid the looming TikTok ban.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against Trump and US policies. In a playful act of political defiance, they downloaded Xiaohongshu to show they weren’t scared of government warnings about Chinese data collection. (For clarity: while TikTok is a made-in-China app, it is not accessible inside mainland China, where Douyin is the domestic version run by the same parent company).

The influx of foreigners — who were quickly nicknamed “TikTok refugees” — soon turned into a moment of cultural celebration. As American creators introduced themselves, Chinese users welcomed them warmly, eager to practice English and teach newcomers how to navigate the app. Discussions about language, culture, and societal differences flourished. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor. It was a rare moment of social media doing what we hope it can do: connect people, build bridges, and replace prejudice with curiosity.

Some of that same enthusiasm was also visible during IShowSpeed’s China tour. Despite the tour inevitably getting entangled with political and commercial interests, much of it was simply about an American boy swept up in the high energy of China’s vibrant cities and everything they offer.

Different from IShowSpeed, who is known for his meme-worthy online presence, Piker is primarily known for his radical political views. His China enthusiasm feels driven less by cultural curiosity and more by his critique of America.

Because of his stances — such as describing the US as a police state — it’s easy for Western critics to accuse him of hypocrisy in praising China, especially after a brief run-in with security police while livestreaming at Tiananmen Square.

Seen in broader context, Piker’s China trip reflects a shift in how China is used in American online discourse.

Before, it was Chinese ‘public intellectuals’ (公知) who praised the US as a ‘lighthouse country’ (灯塔国), a beacon of democracy, to indirectly critique China and promote a Western modernization model. Later, Chinese online influencers showcased their lives abroad to emphasize how much ‘brighter the moon’ was outside China.

In the post-Covid years, the current reversed: Western content creators, from TikTok influencers to political commentators, increasingly use China to make arguments that are fundamentally about America.

Between these cycles, authentic cultural curiosity gets pushed to the sidelines. The TikTok-refugee moment in early January may have been the closest we’ve come in years: a brief window where Chinese and American users met each other with curiosity, camaraderie, and creativity.

Hasan’s tour, in contrast, reflects a newer phase, one where China is increasingly used as a stage for Western political identity rather than a complex and diverse country to understand on its own terms. I think the honeymoon phase is over.

“Liu Sihan, Your School Uniform Ended Up in Angola”: China’s Second-Hand Clothing in Africa

A Chinese school uniform went viral after a Chinese social media user spotted it in Angola.

“Liu Sihan, your schooluniform is hot in Africa” (刘思涵你的校服在非洲火了) is a sentence that unexpectedly trended after a Chinese blogger named Xiao Le (小乐) shared a video of a schoolkid in Angola wearing a Chinese second-hand uniform from Qingdao Xushuilu Primary School, that had the nametag Liu Sihan on it.

The topic sparked discussions about what actually happens to clothing after it’s donated, and many people were surprised to learn how widely Chinese discarded clothing circulates in parts of Africa.

Liu Sihan’s mother, whose daughter is now a 9th grader in Qingdao, had previously donated the uniform to a community clothing donation box (社区旧衣回收箱) after Liu outgrew it. She intended it to help someone in need, never imagining it to travel all the way to Africa.

In light of this story, one netizen shared a video showing a local African market selling all kinds of Chinese school items, including backpacks, and people wearing clothing once belonging to workers for Chinese delivery platforms. “In Africa, you can see school uniforms from all parts of China, and even Meituan and Eleme outfits,” one blogger wrote.

When it comes to second-hand clothing trade, we know much more about Europe–Africa and US–Africa flows than about Chinese exports, and it seems there haven’t been many studies on this specific topic yet. Still, alongside China’s rapid economic transformations, the rise of fast fashion, and the fact that China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of textiles, the country now has an enormous abundance of second-hand clothing.

According to a 2023 study by Wu et al. (link), China still has a long way to go in sustainable clothing disposal. Around 40% of Chinese consumers either keep unwanted clothes at home or throw them away.

But there may be a shift underway. Donation options are expanding quickly, from government bins to brand programs, and from second-hand stores to online platforms that offer at-home pickup.

Chinese social media users posting images of school/work uniforms from China worn by Africans.

As awareness grows around the benefits of donating clothing (reducing waste, supporting sustainability, and the emotional satisfaction of giving), donation rates may rise significantly. The story of Liu Sihan’s uniform, which many found amusing, might even encourage more people to donate. And if that happens, scenes of African children (and adults) wearing Chinese-donated clothes may become much more common than they now are.

Laojunshan: New Hotspot in Cold Winter

Images from Xiaohongshu, 背包里的星子, 旅行定制师小漾

Go to Zibo for BBQ, go to Tianshui for malatang, go to Harbin for the Ice Festival, cycle to Kaifeng for soup dumplings, or head to Dunhuang to ride a camel — over recent years, a number of Chinese domestic destinations have turned into viral hotspots, boosted by online marketing initiatives and Xiaohongshu influencers.

This year, Laojunshan is among the places climbing the trending lists as a must-visit spot for its spectacular snow-covered landscapes that remind many of classical Chinese paintings. Laojunshan (老君山), a scenic mountain in Henan Province, is attracting more domestic tourists for winter excursions.

Xiaohongshu is filled with travel tips: how to get there from Luoyang station (by bus), and the best times of day to catch the snow in perfect light (7–9 AM or around 6–6:30 PM).

With Laojunshan, we see a familiar pattern: local tourism bureaus, state media, and influencers collectively driving new waves of visitors to the area, bringing crucial revenue to local industries during what would otherwise be slower winter months.

WeChat New Features & Hong Kong Police on Douyin

🟦 WeChat has been gradually rolling out a new feature that allows users to recall a batch of messages all at once, which saves you the frantic effort of deleting each message individually after realizing you sent them to the wrong group (or just regret a late-night rant). Many users are welcoming the update, along with another feature that lets you delete a contact without wiping the entire chat history. This is useful for anyone who wants to preserve evidence of what happened before cutting ties.

🟦The Hong Kong Police Force recently celebrated its two-year anniversary on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), having accumulated nearly 5 million followers during that time. To mark the occasion, they invited actor Simon Yam to record a commemorative video for their channel (@香港警察). The presence of the Hong Kong Police on the Chinese app — and the approachable, meme-friendly way they’ve chosen to engage with younger mainland audiences — is yet another signal of Hong Kong institutions’ strategic alignment with mainland China’s digital infrastructure, a shift that has been gradually taking place. The anniversary video proved popular on Douyin, attracting thousands of likes and comments.

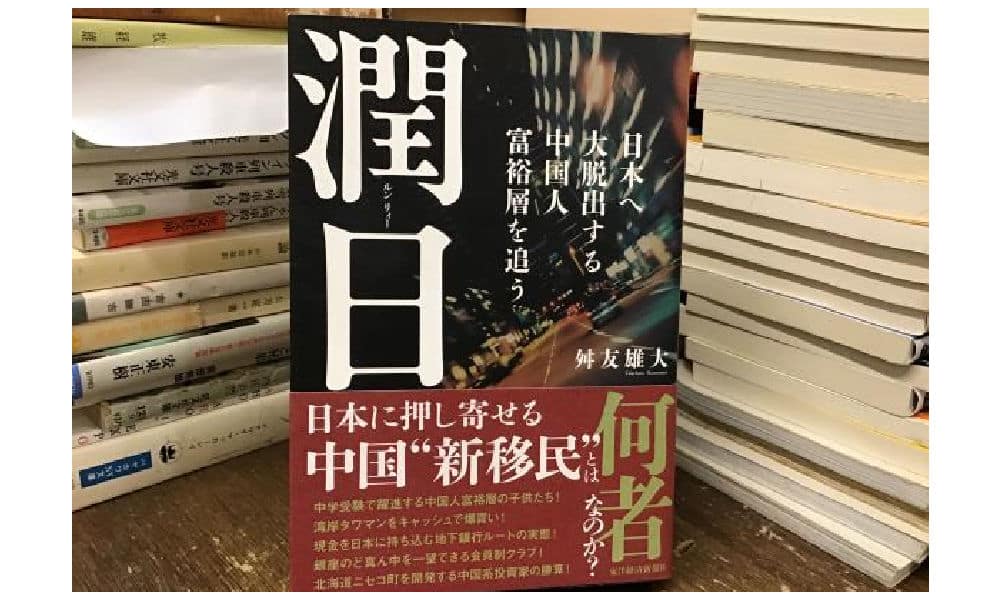

Why Chinese Elite Rùn to Japan (by ChinaTalk)

Over the past week, Japan has been trending every single day on Chinese social media in light of escalating bilateral tensions after Japanese PM Takaichi made remarks about Taiwan that China views as a direct military threat. The diplomatic freeze is triggering all kinds of trends, from rising anti-Japanese sentiment online and a ban on Japanese seafood imports to Chinese authorities warning citizens not to travel to Japan.

You’d think Chinese people would want to be anywhere but Japan right now — but the reality is far more nuanced.

In a recent feature in ChinaTalk, Jordan Schneider interviewed Japanese journalist & researcher Takehiro Masutomo (舛友雄大) who has just published a book about Japan’s new Chinese diaspora, explaining what draws Chinese dissidents, intellectuals, billionaires, and middle-class families to Tokyo.

The book is titled Run Ri: 潤日 Following the Footsteps of Elite Chinese Escaping to Japan (only available in Japanese and Traditional Chinese for now). (The word Rùn 润/潤, by the way, is Chinese online slang and meme expresses the desire to escape the country.)

A very interesting read on how Chinese communities are settling in Japan, a place they see as freer than Hong Kong and safer than the U.S., and one they’re surprisingly optimistic about — even more so than the Japanese themselves.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China Signals. For fast-moving trends and deeper dives, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you just so happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

A small housekeeping note:

This Eye on Digital China newsletter is co-published for subscribers on both Substack and the main site. If you’re registered on both platforms, you’ll receive duplicate emails — so if that bothers you, please pick your preferred platform and unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Society

How Female Comedians Are Shaping China’s Stand-Up Boom

Female comedians are taking center stage in a new era of Chinese stand-up, challenging stereotypes and turning jokes into real-life impact.

Published

6 months agoon

August 30, 2025

Nearly 40% of the lineup on China’s latest hit stand-up comedy shows is female. From ‘Director Fang’ to Wang Yue, this wave of new voices is not just funny—it’s reshaping China’s comedy scene and opening conversations once considered off-limits.

The summer of 2025 has once again put Chinese stand-up comedy in the spotlight. The second season of both iQiyi’s The King of Stand-up Comedy (喜剧之王单口季) and Tencent Video’s Stand-up Comedy and Friends (脱口秀和Ta的朋友们) sparked multiple trending topics across social media—not just for the jokes, but for who’s telling them.

This year, women account for nearly 40% of the combined lineups: 42 out of 107 comedians across both shows.

Just a decade ago, when Tonight 80s Talk Show (今晚80后脱口秀) dominated the field, there was often only one woman—Siwen (思文)—on stage. Even last year, women only made up 24% of The King of Stand-up Comedy’s debut lineup and 27% of Stand-up Comedy and Friends’.

With more women performing, audiences are hearing more stories rooted in lived experiences, touching on relationships, workplace dynamics, and everyday challenges faced by women.

The Rise of New Female Voices

One of the most talked-about breakouts is 50-year-old Fang Zhuren (房主任, literally “Director Fang”).

Her entry into the stand-up comedy world came by chance during an audience interaction. During a performance by Li Bo (李波), a talk show actress, Fang was randomly selected for an interaction with Li. Her nickname “Director Fang” stems from her spontaneous response, as she humorously introduced herself as the “director of the village information center (or the village gossip hub).”

This interaction impressed Li and eventually led her to a contract signing with Li’s talk show* club. Weibo netizens summarized this story with the label of “girls help girls” (#房主任李波girls help girls#).

[*This use of ‘talk show’ refers to the Chinese tuokou xiu 脱口秀, which usually does not refer to a Western-style talk show but (live) stand-up comedy.]

Fang Zhuren (房主任)

Fang’s debut on The King of Stand-up Comedy 2 highlighted the struggles of rural women caught between traditional expectations and harsh realities. Her act, drawing on her own life as an unhappily married rural housewife seeking independence, was even hailed online as the “talk show version” of Like a Rolling Stone (#房主任脱口秀版出走的决心#), referencing the film about China’s “road trip auntie” Su Min (苏敏), who left behind domestic life to pursue freedom.

Other female performers are also making their mark with sharp, personal perspectives:

From left to right: Wang Yue王越, Bu Jingyun (步惊云), Xiaopa (小帕).

🔹 Wang Yue (王越) often addresses the under-discussed topic of menstrual pain, a routine yet overlooked experience for many women.

🔹 Bu Jingyun (步惊云) critiques traditional chastity expectations, referencing the tragic case of a young woman driven to suicide by malicious rumors. She uses the metaphor of “a robot with foot binding going to space” to expose the absurdity of outdated moral codes in modern life.

🔹 Xiaopa (小帕), a young comedian from Xinjiang, draws humor from her turbulent family life. She portrays her father—a man who wasted savings and cycled through marriages—as a “50-year-old boy who never grew up.”

Such routines have sparked heated debates online, many extending far beyond comedy into wider social issues, particularly gender dynamics.

When the Punchline Draws a Battle Line

On July 20, Zhejiang Xuanchuan (浙江宣传), a WeChat account affiliated with the Zhejiang government, published an article titled “Beware of Talk Shows Slipping into the Quagmire of Gender Antagonism” (“谨防脱口秀滑向性别对立的泥潭“).

The controversial article

The article warned against “lazy gender gags” that pit men and women against each other, suggesting comedy should strive for “constructive offense” (建设性冒犯) rather than deepening resentment.

The article has found support among readers but also sparked a wave of retort from some netizens. Some argued that it overlooked the value of talk show actresses in exposing real-life hardships faced by women.

They questioned whether the accusation of “gender antagonism” was, in fact, masking deeper gender inequalities–some netizens argued that male comedians have long relied on sexist jokes.

Examples resurfaced online, such as top comedian Li Dan (李诞) mocking actress Liu Yan (柳岩), or comedian Chi Zi (池子) making offensive remarks about actress Wang Lin (王琳).

The timing added fuel to the fire. On the day the article was published, residents in Hangzhou’s Yuhang District were complaining of foul-smelling tap water, suspected to be sewage, yet local media like Zhejiang Xuanchuan focused on “female talk shows” over a pressing local issue.

A Weibo user wrote: “Between the choice of checking if it is algae or feces in the water pipes, Zhejiang chose to check the talk shows instead.”

Just as the backlash was cooling, veteran entrepreneur Luo Yonghao (罗永浩) reignited the debate.

As a guest on Stand-up Comedy and Friends 2, Luo reposted a review from a viewer who criticized him and host Zhang Shaogang (张绍刚), while praising well-known Chinese stand-up comedian Pang Bo (庞博) on rival show The King of Stand-up Comedy 2. Luo defended Zhang but lashed out at the reviewer, later turning his criticism toward female fan culture.

Responding to netizens, Luo argued that women’s behavior toward male idols was excessively indulgent. He further claimed that admiration for Pang Bo was largely driven by appearance, dismissing it as little more than “looks-based favoritism.”

In a lengthy follow-up post titled “A Veteran Feminist’s Last Piece of Paternalistic Advice” (“老牌女权主义者最后的“爹味儿忠告”), Luo described himself as a longtime feminist but warned against comedians “exploiting” gender issues for cheap laughs. If the industry continues down this path, he argued, it risks “industry-wide collapse.”

Beyond Gender: Comedy as Social Mirror

While topics related to gender and feminism have become a proven traffic driver, another rising theme in Chinese stand-up is comedians transforming personal struggles into humor.

One of them is Xiaopa (小帕), who has openly discussed living with bipolar disorder. By joking about her own diagnosis, she offers the audience a rare mix of vulnerability and wit.

🔹 Then there is Chen Ai (陈艾), who has lived with depression and anxiety. She dryly joked about her visit to a psychiatric hospital that “the depression and anxiety test was the only exam I ever scored high on,” while poking fun at the absurdity of psychiatric questionnaires.

Chen Ai (陈艾)

🔹 Wang Ying (王颖) brings her breast cancer experience into her comedy sets, jokingly calling it a “new comedy track” she has opened up, making breast cancer a subject of shared laughter.

Wang Ying (王颖)

Before them, physically disabled stand-up comedians were already gaining popularity in China, such as Hei Deng (黑灯), who is blind, and Xiao Jia (小佳), a rising star with cerebral palsy. Both earned recognition from netizens by telling jokes about their disabilities and the experiences that came with them.

Hei Deng (黑灯) on the left, and Xiao Jia (小佳) on the right.

These performances show how stand-up comedy can spark laughter while simultaneously addressing deeper social issues.

Some audience members, however, feel such heavy topics weigh down the art form, arguing that comedy should remain funny and light. Others argue the stage itself is a public space, reflective of society at large, where laughter is only one layer, and deeper reflection is inevitable.

But beyond reflection, these comedians can translate humor into real, practical impact.

Hei Deng once joked about strips of tactile paving made from slippery steel—meant to guide the visually impaired, it instead put them in harm’s way on rainy days. The clip went viral, and surprisingly, city officials in Shenzhen soon replaced the material and fixed the problem. A simple gag actually ended up changing public infrastructure.

Hei joked about these paves that are meant to guide visually impaired pedestrians, but actually makes them slip after the rain (source).

Fixing the slippery steel guidance for visually impaired.

The same kind of dynamic plays out when female comedians bring menstruation, cramps, or the burdens of motherhood on stage. These are not just personal stories or “women’s issues.”

When Wang Yue joked about menstrual pain on stage, show guest Guo Qilin (郭麒麟)—a well-known Chinese actor and xiangsheng (相声, or crosstalk) performer—remarked that her performance didn’t sound like a complaint, but more like a science lecture— allowing many male viewers to better understand the experience for the first time. His reaction underscores a quiet truth: when women’s experiences are silenced, men also lose the chance to understand, empathize, and adjust their behavior.

Host Chen Luyu (陈鲁豫): “Women make up half of humanity, and the female perspective is, in fact, the human perspective.”

Gender stereotypes don’t just confine women; they warp expectations for everyone. Take menstrual pain, for example. It isn’t only about the suffering women endure, but also about arguments between couples, company leave policies, and even restroom design. Likewise, son preference is not just about undervaluing women; it also places crushing pressure on young men, who are expected to buy an apartment before getting married. In other words, when women’s issues are properly addressed, everyone benefits.

As host Chen Luyu (陈鲁豫) put it, “Women make up half of humanity, and the female perspective is, in fact, the human perspective.”

Luckily, more women are stepping into the spotlight, reshaping China’s stand-up scene, and opening conversations that were once considered off-limits.

And this is just the beginning. As comedian Pang Bo observed: “They (她们, specifically women) still have a lot of issues to discuss with everyone.”

As both the iQiyi and Tencent competitions head toward their finals in early September, many wonder if a female comedian will take the crown this year?

Whatever the outcome, the stage has already changed.

By Wendy Huang

Edited by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at

info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive9 months ago

Chapter Dive9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West