Nothing Sacred: ‘Maskpark Gate’ & Karmic Justice

Published

2 days agoon

Dear Reader,

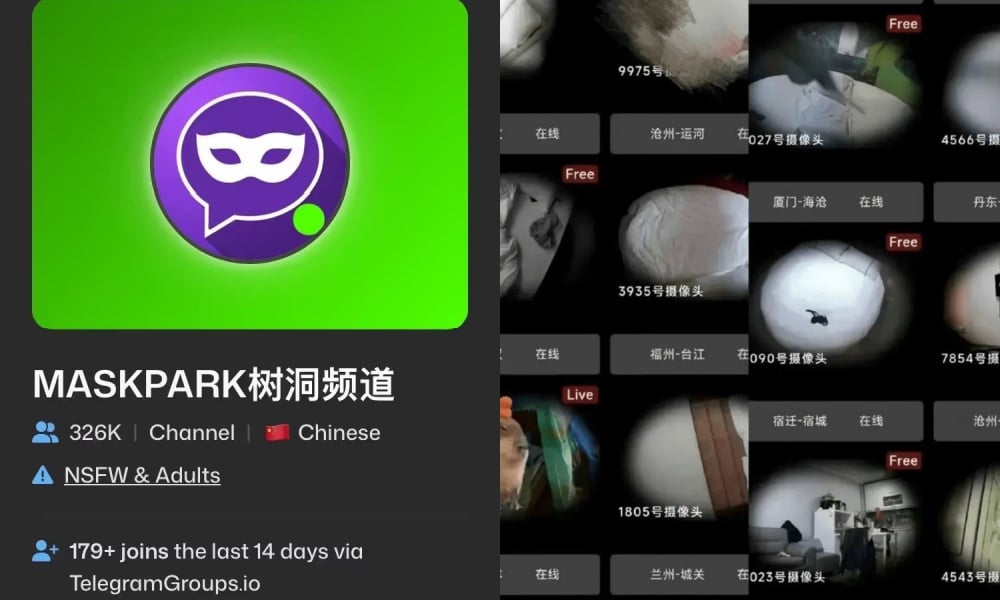

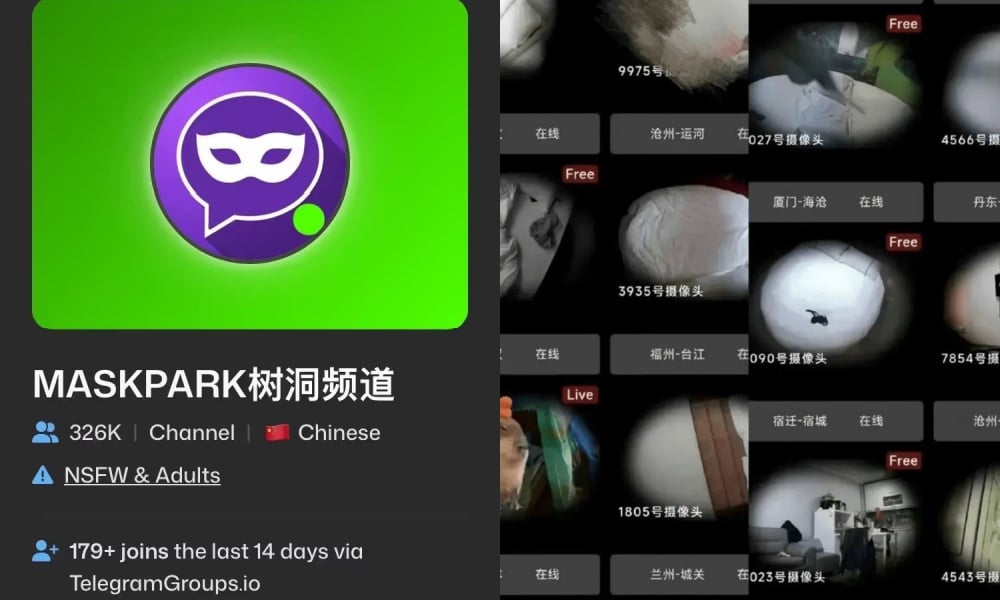

Earlier this month, a female Weibo user nicknamed “The Armpit-Haired Dude” (@腋毛大汉) posted an exposé on Weibo, revealing the existence of a large-scale anonymous Chinese-language sex exploitation and voyeuristic content community on the encrypted messaging app Telegram.

In this Telegram network called “Maskpark Treehole Forum” (面具公园树洞论坛), participants shared hidden camera footage, non-consensual intimate videos, and fetishised depictions of thousands of women. (The word “treehole” or “tree hollow” 树洞 refers to a place of anonymous confessions.)

News of the community spread across social media like wildfire and set off a storm of outrage.

It soon became clear that what was happening within this network was deeply disturbing, and that the scale of the activities was enormous.

“Maskpark” had over 100,000 active members—mostly Chinese men—and dozens of sub-channels, each with tens of thousands of members sharing images and footage, impacting countless victims.

There were all kinds of victims whose images and videos were shared in these groups in dozens of ways.

Some girls were recorded with hidden pinhole cameras in public bathrooms; some women’s videos were taken through private home surveillance; some females were unknowingly recorded in hotels or even hospitals; some were simply taking the subway when unknowingly filmed up their skirts; some material was taken from private social media accounts.

Some of the women were the sharers’ own sisters, mothers, girlfriends, wives, colleagues, or even daughters—exposed to thousands of online strangers for sexual gratification.

The group even had a specific term for this practice of sharing women’s images and videos: “offering tributes” (shàng gòng 上供).

Soon, netizens linked ‘Maskpark’ to a man named Mai Zihao (麦梓豪), known online as @麦Mako, who had previously operated a dating app also called Maskpark. On that platform, men had to be invited and pay to meet women online. The app ran for two years before it was taken offline in 2020 as an illegal mobile application. Among other issues, the platform routinely turned a blind eye to explicit content and sex work taking place on its network.

In response to the online accusations, Mai initially issued a brief statement denying any involvement with the Maskpark Telegram community, but then proceeded to wipe all his social media accounts across every platform, which only further fueled suspicions.

Meanwhile, the Maskpark Telegram group was switched to private, and is now no longer searchable on the app.

On Chinese social media, frustration has continued to grow as days — now weeks — have passed without a single word from Chinese authorities. So far, there have been no reports of any official investigations into the key individuals involved in the Telegram group.

Telegram, which was founded by Russian tech entrepreneurs Pavel and Nikolai Durov in 2013, is officially blocked in mainland China. The app company is headquartered in Dubai.

“It’s not China’s Nth Room”

The ‘Maskpark incident’ is now also widely referred to as the “Chinese Nth Room” (中国版N号房). The original Nth Room scandal made headlines in South Korea in August 2019, after the existence of a vast Telegram chat network involving blackmail, cybersex trafficking, and the distribution of sexually exploitative videos—run by South Korean men—was exposed.

But some argue that calling the Maskpark scandal the “Chinese Nth Room” oversimplifies the issue and obscures its broader scale.

“There isn’t just one Nth Room in China, there are many,” Weibo user Fanzhexi (@饭哲惜) wrote, compiling a list of digital sex scandals that have been labeled as “China’s Nth Room” in recent years.

Among them, the following incidents:

- 2019: Twitter users uncovered numerous Chinese-language accounts selling date-rape drugs. They launched a widespread campaign under the hashtag #ChinaWakeUp, hoping to draw attention from Chinese women and authorities. But these voices barely made it through China’s Great Firewall and eventually faded into silence.

- 2022: Weibo user Liangzhou (@梁州Zz) exposed an online child sexual exploitation forum with nearly 50,000 members. This was a disturbingly active community sharing videos sexually exploiting underage girls, even with detailed tactics on how to lure victims using sweet words and small gifts.

- 2023: BBC Eye released a documentary titled Catching a Pervert: Sexual Assault for Sale, following a year-long investigation into a public molestation and hidden-camera sexual exploitation ring run by a group of young Chinese men living in Japan. The filmmakers even tracked down the ringleaders, whose identities were later published on Chinese social media platforms.

- 2024: Chinese netizens uncovered a paid website streaming live feeds from pinhole cameras. Rumors circulating on Weibo suggested the platform had as many as 140,000 members. The revelation sparked fierce online debate, yet no major media outlets covered the story.

And all of this is still only scratching the surface, leading to growing public questions about why those responsible haven’t been brought to justice.

This is also one of the reasons why some online commentators think that this digital sex scandal, as well as previous ones, shouldn’t be lumped under the “Chinese Nth Room” label.

After the scandal broke in South Korea, politicians and authorities swiftly acted to step up against these kinds of crimes. A special task force was set up, suspects were arrested, and stricter laws were introduced to crack down on secret filming and the distribution of exploitative videos.

In contrast, online commenters argue, recent years have shown that Chinese authorities have responded with less urgency and toughness to similar crimes, such as in the cases mentioned above.

“I was the one being secretly filmed”

Another major issue fueling the whirlwind of emotion and anger on Chinese social media is the censorship of articles, comments, hashtags, and posts related to ‘Maskpark Gate.’ The story is being kept off trending search lists, and searching #maskpark# or #麦梓豪# (Mai Zihao) on Weibo returns the message: “Sorry, this topic content cannot be displayed.”

Since awareness of the case has been driven by online sleuths, concerned netizens, and female victims, their goal is to amplify their voices so that authorities will take action.

But instead of being heard, they see their posts getting deleted—while seeing no progress in how the case is being handled.

“I’ve lost faith,” one user despairingly posted on Weibo “It feels like we’re stuck in a vicious cycle: anger, helplessness, forced forgetting, and then anger again. The harm has been done multiple times, but there’s been no progress.”

Others are beginning to feel a sense of apathy, questioning whether continuing to raise awareness even makes a difference. One Xiaohongshu user wrote: “We just endlessly pass along broken bits to those who already broke it into pieces. Eventually, there’s nothing left for us to break. Once it turns to dust, a gust of wind will blow it all away.”

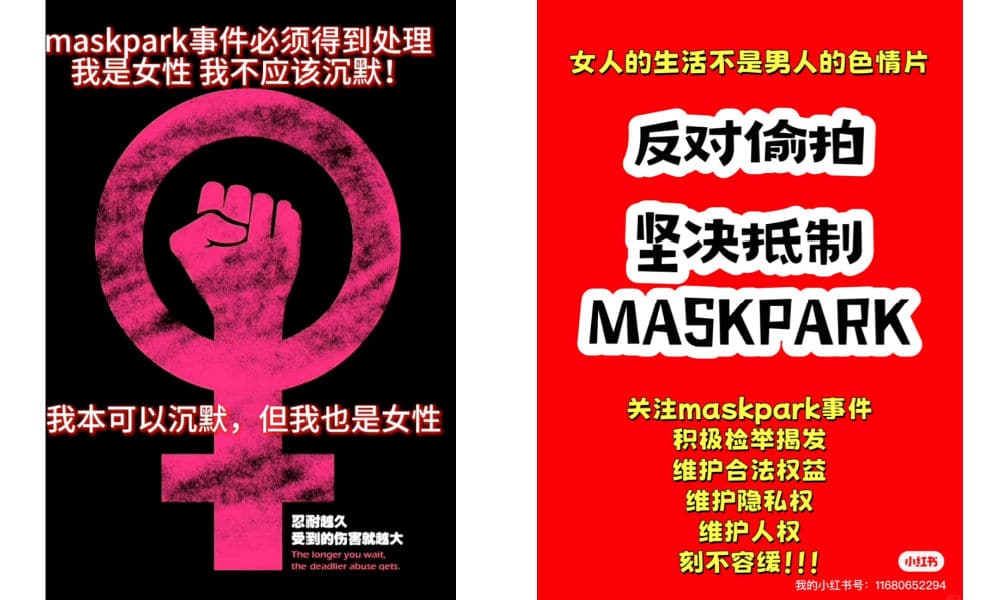

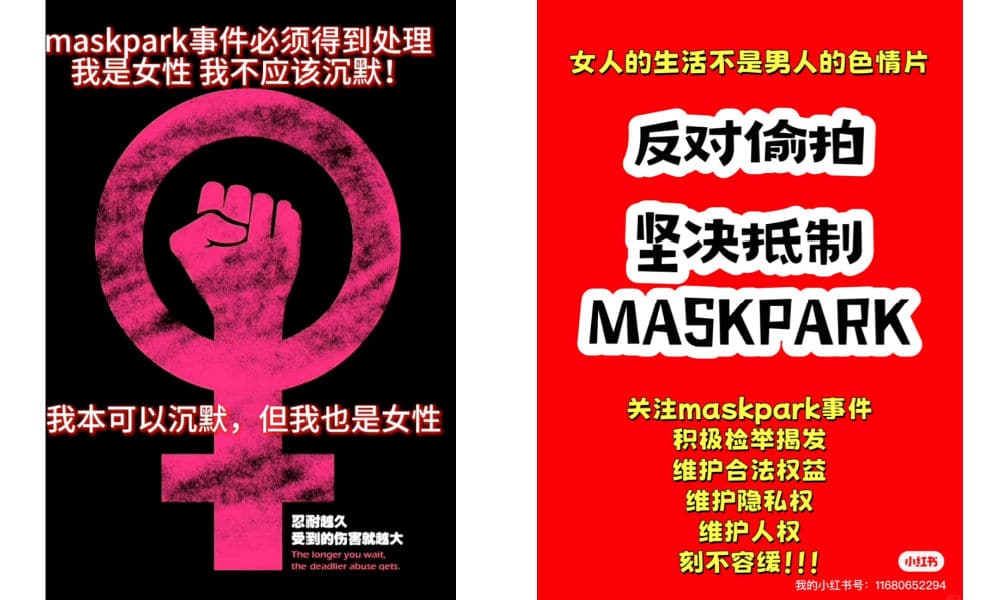

Some have turned to creating digital art and letting the images speak for them.

By now, the case feels like an elephant in the room across platforms like Weibo, Douyin, and Xiaohongshu, where many are left wondering: who is actually standing up against sexual exploitation and for women’s safety?

One protest sign says: “Women’s lives are not a porn movie for men. Fight against secret filming. Stand up against Maskpark.”

Another protest phrase is “The one who was secretly recorded is me” (“被偷拍的就是我”), suggesting that every woman is potentially a victim of Maskpark. Those who haven’t been alerted by someone have no way of knowing if they’re among the thousands of videos and images circulating within the community.

Others point out that this scandal reveals how advanced and precise hidden camera technologies have become, making this not just a women’s issue, but a serious national problem.

Waiting for Karma

A major aspect of the Maskpark scandal is the shocking way thousands of Chinese men used their own female family members, friends, and colleagues as content to “offer tributes” to the Telegram group—exposing those they were meant to protect.

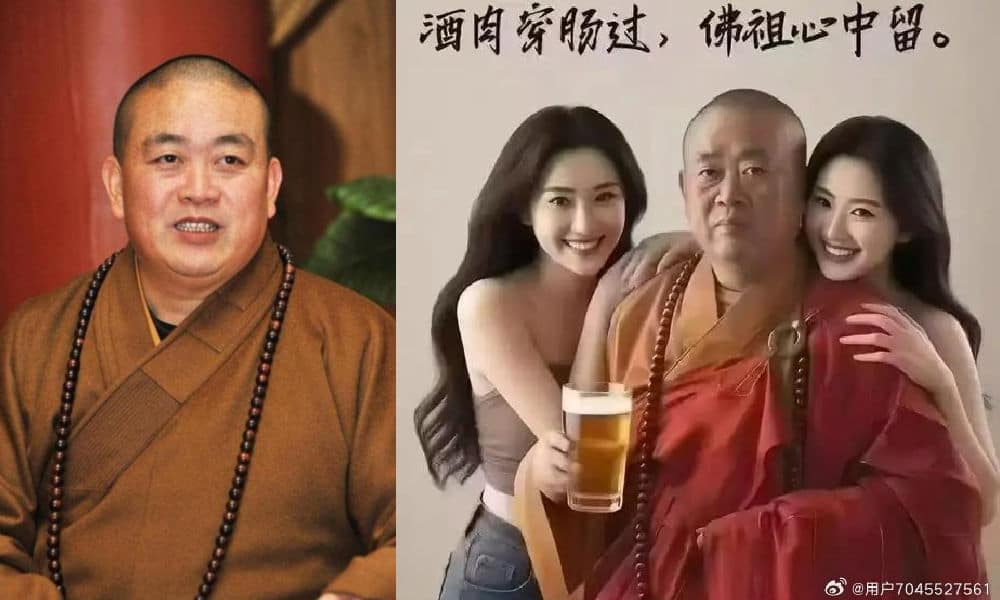

In another scandal dominating Chinese social media this week, one of the country’s well-known Buddhist monks—Shi Yongxin (释永信), the abbot of the world-famous Shaolin Temple—was revealed to be a money-grabbing playboy who embezzled temple funds, had multiple affairs, and fathered illegitimate children.

Shi Yongxin, who also was an active Weibo user sharing Buddhist wisdoms, had been at the Shaolin Temple since 1981. In our latest featured article, we explore how the controversy unfolded and what has happened since.

Though entirely different in nature, both the Maskpark and Shaolin scandals have been called just “the tip of the iceberg” (冰山一角) by netizens who believe these events represent far broader, systemic problems.

One part of the Shaolin scandal that has raised discussions is that one of Shi Yongxin’s disciples, Shi Yanlu (释延鲁), had already tried to raise the alarm about the abbot’s ethical, monastic, and financial misconduct ten years ago. Together with fellow monks, Shi Yanlu submitted a fifty-page formal complaint detailing the abbot’s fraudulent behavior and sexual misconduct in 2015.

However, the Henan provincial investigation concluded that the accusations lacked evidence, and no action was taken, allowing Shi Yongxin to continue a temple career marked by embezzlement and affairs for another decade.

People therefore feel that Shi Yongxin’s fall from his Buddhist throne is just one part of the story — there was a structure in place that kept him in power for many years, protected by those in various positions who turned a blind eye to his wrongdoings.

The Shi Yongxin scandal has negatively impacted public perception of monasteries and monks across China. If a monk in such a high and influential position could stray so far from the Buddhist path, what does that say about the rest? Where do temple donations go? Have Chinese temples become mere “chessboards for capital” (资本的棋盘), as one person wondered, where dirty games are played on the backs of believers?

Both the Maskpark incident and the Shaolin scandal reveal that nothing feels sacred anymore — not a woman’s privacy in a public bathroom, not a monk’s vows in a sacred temple.

If there’s one thing that remains, though, it’s karma.

In the case of Shi Yongxin, commenters wrote that karma has come for him (“如今他的因果报应终于来了”); he’s been stripped of his title, arrested, and is now awaiting the legal consequences of his misdeeds.

In the case of the key figures behind the Maskpark groups and all those men who “offered tributes,” netizens can only hope that karma will come for them, too.

Best,

Manya Koetse & Ruixin Zhang

What’s Featured

A deeper dive behind the hashtag

Bad Karma | This trending story is bound to have implications for Chinese religious, social, and political spheres in various ways. Shi Yongxin is a well-known head monk of the world-renowned Shaolin Temple. Although we’re not exactly sure yet about the scope of his misdeeds, we do know he has embezzled a lot of money, had a very active love life, and fathered multiple illegitimate children. His actions and arrest will inescapably affect Chinese monastery spheres and the public’s perceptions of them. Click to read more.

Something in the Water | Earlier this month, locals in Yuhang, a district of Hangzhou, noticed something fishy about their running water. It had turned brown, and smelled unpleasant. While residents were worried about ‘poop water’ coming from their tap, they also became angry about how slow the local officials were in giving them more information about what was actually going on. Read more in this featured article here.

What Else Is Trending

Hot topics at a glance

⛈️ Extreme rain in Beijing | Over the past week, the two characters “暴雨” have been among the biggest topics on Chinese social media, meaning rainstorm (bàoyǔ). Beijing and neighboring regions have experienced days of torrential rain, with serious consequences. In Miyun, a mountainous district in the north, the rain triggered floods that trapped residents inside their homes. More than 30 people have been killed in the extreme weather and flooding.

🏭 Six Chinese students dead after falling into flotation tank during mine visit | A tragic accident at a mineral processing plant that killed six Chinese students in Inner Mongolia became a major topic of discussion over the past week. The incident occurred on July 23, when the students, all studying engineering at Northeastern University, visited the plant as part of their studies and fell into a flotation tank used for mineral processing after a metal grate above the tanks collapsed. The tank was deep and the slurry inside made it impossible to swim. By the time the students were taken out of the tank, they had already drowned. Read more about the incident here.

🎬 Dead to Rights | A new Chinese war movie has become a major talking point on Chinese social media. Loosely based on a true story, Dead to Rights (南京照相馆) is about a group of young Chinese who take refuge in a photography studio during the Japanese invasion and brutal occupation of Nanjing in 1937, at the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. When a Japanese military photographer asks them to develop his films, they discover the atrocities occurring beyond the studio walls. The film is being promoted by Chinese official media as a testament to history, but it also evokes some strong emotional responses among moviegoers about a horrific past that, as most commenters express, should never be forgotten. We’ll cover more about this movie in the upcoming week.

What’s Noteworthy

Small news with big impact

FreeWeibo, FreeZhihu, and FreeWeChat are platforms with a mission: in the fight against censorship, they uncover search terms blocked on Chinese social media platforms — Weibo, Zhihu, and WeChat — providing insights into exactly what content gets taken offline. These projects, some already live for over a decade, are run by GreatFire.org, which uses AI to monitor censorship in China and beyond.

Now, GreatFire is under fire themselves. Tencent, the tech giant behind WeChat, has taken legal action to shut down FreeWeChat, citing trademark and copyright infringement. GreatFire, however, sees the claim as a thin pretext “to mask what is clearly a politically motivated act of censorship.”

While one hosting provider complied and removed an instance of the site, the FreeWeChat domain is still live. Its X account, however, has been suspended, reportedly due to Tencent’s trademark complaints.

Still, GreatFire says it will fight to keep its platforms live, writing on X:

“Hey @ElonMusk! As free speech absolutists, why is X playing Tencent’s censorship game? We’re just archiving WeChat’s deleted truths — like a digital museum of the forbidden. Absolute free speech… unless trademarks are involved? Let’s uncensor the censors!”

What’s Popular

The latest obsession on China’s internet

“Rat people” (lǎoshǔrén 老鼠人) is a term that has become popular online in China over the past few months to describe a lifestyle marked by low energy, staying in bed, doomscrolling on the phone during the night, ordering food online, and sleeping the day away.

It’s a lifestyle that’s blown up on Douyin and Xiaohongshu, where young Chinese people are documenting and sharing these kinds of “rat lifestyles.”

In this short feature about the “rat people” movement, I spoke with CNN about what’s behind this trend. Watch here.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed the last newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know. No longer wish to receive these newsletters? You can unsubscribe at any time while remaining a premium member.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Dear Reader

Waiting for Karma in the Maskpark Scandal

From Telegram to Shaolin Temple, the two scandals that rocked Chinese social media this week.

Published

2 days agoon

August 3, 2025

🔥 This column also appeared in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Earlier this month, a female Weibo user nicknamed “The Armpit-Haired Dude” (@腋毛大汉) posted an exposé on Weibo, revealing the existence of a large-scale anonymous Chinese-language sex exploitation and voyeuristic content community on the encrypted messaging app Telegram.

In this Telegram network, called “Maskpark Treehole Forum” (面具公园树洞论坛), participants shared hidden camera footage, non-consensual intimate videos, and fetishised depictions of thousands of women. (The word “treehole” or “tree hollow” 树洞 refers to a place of anonymous confessions.)

News of the community spread across social media like wildfire and set off a storm of outrage, as it soon became clear that what was happening within this network was deeply disturbing, and that the scale of the activities was enormous.

“Maskpark” had over 100,000 active members—mostly Chinese men—and dozens of sub-channels, each with tens of thousands of members sharing images and footage, impacting countless victims.

There were all kinds of victims whose images and videos were shared in these groups in dozens of ways.

Some girls were recorded with hidden pinhole cameras in public bathrooms; some women’s videos were taken through private home surveillance; some females were unknowingly recorded in hotels or even hospitals; some were simply taking the subway when unknowingly filmed up their skirts; some material was taken from private social media accounts.

Some of the women were the sharers’ own sisters, mothers, girlfriends, wives, colleagues, or even daughters—exposed to thousands of online strangers for sexual gratification.

The group even had a specific term for this practice of sharing women’s images and videos: “offering tributes” (shàng gòng, 上供).

Soon, netizens linked ‘Maskpark’ to a man named Mai Zihao (麦梓豪), known online as @麦Mako, who had previously operated a dating app also called Maskpark. On that platform, men had to be invited and pay to meet women online. The app ran for two years before it was taken offline in 2020 as an illegal mobile application. Among other issues, the platform routinely turned a blind eye to sex work and explicit transactions taking place on its network.

In response to the online accusations, Mai initially issued a brief statement denying any involvement with the Maskpark Telegram community, but then proceeded to wipe all his social media accounts across every platform, which only further fueled suspicions.

Meanwhile, the Maskpark Telegram group was switched to private, and is now no longer searchable on the app.

On Chinese social media, frustration has continued to grow as days — now weeks — have passed without a single word from Chinese authorities. So far, there have been no reports of any official investigations into the key individuals involved in the Telegram group.

Telegram, which was founded by Russian tech entrepreneurs Pavel and Nikolai Durov in 2013, is officially blocked in mainland China. The app company is headquartered in Dubai.

“It’s not China’s Nth Room”

The ‘Maskpark incident’ is now also widely referred to as the “Chinese Nth Room” (中国版N号房). The original Nth Room scandal made headlines in South Korea in August 2019, after the existence of a vast Telegram chat network involving blackmail, cybersex trafficking, and the distribution of sexually exploitative videos—run by South Korean men—was exposed.

But some argue that calling the Maskpark scandal the “Chinese Nth Room” oversimplifies the issue and obscures its broader scale.

“There isn’t just one Nth Room in China, there are many,” Weibo user Fanzhexi (@饭哲惜) wrote, compiling a list of digital sex scandals that have been labeled as “China’s Nth Room” in recent years.

Among them, the following incidents:

- 2019: Twitter users uncovered numerous Chinese-language accounts selling date-rape drugs. They launched a widespread campaign under the hashtag #ChinaWakeUp, hoping to draw attention from Chinese women and authorities. But these voices barely made it through China’s Great Firewall and eventually faded into silence.

- 2022: Weibo user Liangzhou (@梁州Zz) exposed an online child sexual exploitation forum with nearly 50000 members. This was a disturbingly active community sharing videos sexually exploiting underage girls, even with detailed tactics on how to lure victims using sweet words and small gifts.

- 2023: BBC Eye released a documentary titled Catching a Pervert: Sexual Assault for Sale, following a year-long investigation into a public molestation and hidden-camera sexual exploitation ring run by a group of young Chinese men living in Japan. The filmmakers even tracked down the ringleaders, whose identities were later published on Chinese social media platforms.

- 2024: Chinese netizens uncovered a paid website streaming live feeds from pinhole cameras. Rumors circulating on Weibo suggested the platform had as many as 140,000 members. The revelation sparked fierce online debate, yet no major media outlets covered the story—and once again, authorities remained silent.

And all of this is still only scratching the surface, leading to growing public questions about why those responsible haven’t been brought to justice.

This is also one of the reasons why some online commentators think that this digital sex scandal, as well as previous ones, shouldn’t be lumped under the “Chinese Nth Room” label.

After the scandal broke in South Korea, politicians and authorities swiftly acted to step up against these kinds of crimes. A special task force was set up, suspects were arrested, and stricter laws were introduced to crack down on secret filming and the distribution of exploitative videos.

In contrast, online commenters argue, recent years have shown that Chinese authorities have responded with less urgency and toughness to similar crimes, such as in the cases mentioned above.

“I was the one being secretly filmed”

Another major issue fueling the whirlwind of emotion and anger on Chinese social media is the censorship of articles, comments, hashtags, and posts related to ‘Maskpark Gate.’ The story is being kept off trending search lists, and searching #maskpark# or #麦梓豪# (Mai Zihao) on Weibo returns the message: “Sorry, this topic content cannot be displayed.”

Since awareness of the case has been driven by online sleuths, concerned netizens, and female victims, their goal is to amplify their voices so that authorities will take action.

But instead of being heard, they see their posts getting deleted—while seeing no progress in how the case is being handled.

“I’ve lost faith,” one user despairingly posted on Weibo “It feels like we’re stuck in a vicious cycle: anger, helplessness, forced forgetting, and then anger again. The harm has been done multiple times, but there’s been no progress.”

Others are beginning to feel a sense of apathy, questioning whether continuing to raise awareness even makes a difference. One Xiaohongshu user wrote: “We just endlessly pass along broken bits to those who already broke it into pieces. Eventually, there’s nothing left for us to break. Once it turns to dust, a gust of wind will blow it all away.”

Some have turned to creating digital art and letting the images speak for them.

Digital art spread online. Right image by 菠萝菠萝咪, left image original creator unknown.

By now, the case feels like the elephant in the room across platforms like Weibo, Douyin, and Xiaohongshu, where many are left wondering: who is actually standing up against sexual exploitation and for women’s safety?

Examples of protest images and digital posters on Chinese social media.

One protest sign says: “Women’s lives are not a porn movie for men. Fight against secret filming. Stand up against Maskpark.”

Another protest phrase is “The one who was secretly recorded is me” (“被偷拍的就是我”), suggesting that every woman is potentially a victim of Maskpark. Those who haven’t been alerted have no way of knowing if they’re among the thousands of videos and images circulating within the community.

Others point out that this scandal reveals how advanced and precise hidden camera technologies have become, making this not just a women’s issue but a national problem.

Waiting for Karma

A major aspect of the Maskpark scandal is the shocking way thousands of Chinese men used their own female family members, friends, and colleagues as content to “offer tributes” to the Telegram group—exposing those they were meant to protect.

In another scandal dominating Chinese social media this week, one of the country’s well-known Buddhist monks—Shi Yongxin (释永信), the abbot of the world-famous Shaolin Temple—was revealed to be a money-grabbing playboy who embezzled temple funds, had multiple affairs, and fathered illegitimate children.

Shi Yongxin, who also was an active Weibo user sharing Buddhist wisdoms, had been at the Shaolin Temple since 1981. In our latest featured article, we explore how the controversy unfolded and what has happened since.

Left: image of Shaolin abbot Shi Yongxin. Right: AI/photoshopped image made by netizens saying: “Alcohol and meat goes through th stomach, Buddha remains in the heart.”

Though entirely different in nature, both the Maskpark and Shaolin scandals have been called just “the tip of the iceberg” (冰山一角) by netizens who believe these events represent far broader, systemic problems.

One part of the Shaolin scandal that has raised discussions is that one of Shi Yongxin’s disciples, Shi Yanlu (释延鲁), had already tried to raise the alarm about the abbot’s ethical, monastic, and financial misconduct ten years ago. Together with fellow monks, Shi Yanlu submitted a fifty-page formal complaint detailing the abbot’s fraudulent behavior and sexual misconduct in 2015.

However, the Henan provincial investigation concluded that the accusations lacked evidence, and no action was taken, allowing Shi Yongxin to continue a temple career marked by embezzlement and affairs for another decade.

People therefore feel that Shi Yongxin’s fall from his Buddhist throne is just one part of the story — there was a structure in place that kept him in power for many years, protected by those in various positions who turned a blind eye to his wrongdoings.

The Shi Yongxin scandal has negatively impacted public perception of monasteries and monks across China. If a monk in such a high and influential position could stray so far from the Buddhist path, what does that say about the rest? Where do temple donations go? Have Chinese temples become mere “chessboards for capital” (资本的棋盘), as one person wondered, where dirty games are played on the backs of believers?

Both the Maskpark incident and the Shaolin scandal reveal that nothing feels sacred anymore — not a woman’s privacy in a public bathroom, not a monk’s vows in a sacred temple.

If there’s one thing that remains, though, it’s karma.

In the case of Shi Yongxin, commenters wrote that karma has come for him (“如今他的因果报应终于来了”); he’s been stripped of his title, arrested, and is now awaiting the legal consequences of his misdeeds.

In the case of the key figures behind the Maskpark groups and all those men who “offered tributes,” netizens can only hope that karma will come for them, too.

– By Manya Koetse & Ruixin Zhang

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

The Secret Life of Monks: Shi Yongxin’s Shaolin Scandal Casts a Shadow on Monastic Integrity

“To put it bluntly, temples have been places of deception, corruption, opportunism, and exploitation since ancient times.”

Published

1 week agoon

July 28, 2025

This week, news about a well-known Chinese monk going off the Buddhist path has triggered many discussions on Chinese social media.

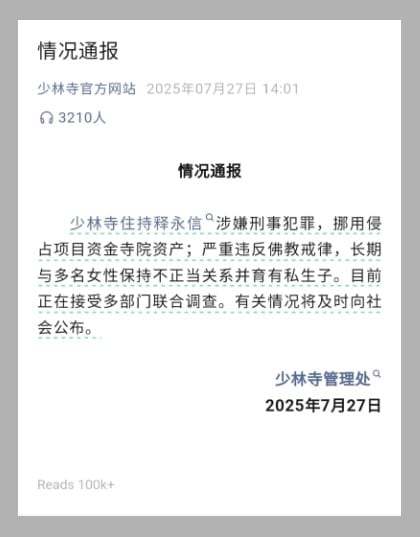

The story revolves around Shi Yongxin (释永信), the head monk at China’s famous Shaolin Temple (少林寺) in Dengfeng, Henan. Shi is suspected of embezzlement of temple funds and illicit relationships, and is currently under investigation.

In recent days, wild rumors have been circulating online claiming that Shi fled to the United States after being exposed. On July 26, a supposed “police bulletin” began circulating, alleging that Shi Yongxin had attempted to leave the country with seven lovers, 21 children, and six temple staff. It also claimed he was stopped by authorities before exiting China, that he had secretly obtained U.S. citizenship a decade ago, and that he had misused donations and assumed fake identities.

Although that specific report has since been refuted by Chinese official media, it quickly became clear that there was real fire behind all that smoke.

The report that circulated online and was later confirmed to be fake

Because despite all the sensationalized gossip (some posts even claimed Shi had 174 illegitimate children!), what’s certain is that Shi Yongxin seriously crossed the line. On July 27, 2025, the Shaolin Temple Management Office (少林寺管理处) issued an official statement through its verified channels, including its WeChat account. The statement read:

The report that circulated online and was later confirmed to be fake.

Shi Yongxin, the Abbot of Shaolin Temple, is suspected of criminal offenses, including misappropriating and taking project funds and temple assets. He seriously violated Buddhist discipline, maintained improper relationships with multiple women over a long period and fathered illegitimate children. He is currently under joint investigation by multiple departments. Relevant information will be made public in due course.

Shaolin Temple Management Office

July 27, 2025

China’s Buddhist Association (中国佛教协会) also released a statement on July 28, in which it stated that, in coordination with the Henan Provincial Buddhist Association (河南省佛教协会), Shi Yongxin has been officially stripped of his monastic status.

Various Chinese media sources report that Shi Yongxin was taken away by police on Friday, July 25. Chinese media outlet Caixin suggests that it must not have come as a complete surprise, since Shi had allegedly already been restricted from leaving the country since around the Spring Festival period (late January 2025) (#释永信春节前后已被限制出境#).

About Shi Yongxin

Shi Yongxin is not just any abbot. He’s the abbot of the Shaolin Monastery (少林寺), which is one of the most famous Buddhist temples in the world and is known as the birthplace of Shaolin Kung Fu. The temple was founded in 495 CE. Besides being a Buddhist monastery, it also operates as a popular tourist attraction, a kung fu school, and a cultural brand.

Shi has been running the monastery for 38 years, a fact that also went trending on Weibo these days (#释永信已全面主持少林寺38年#, 140 million views by Monday).

Shi Yongxin is the monastic name of Liu Yingcheng (刘应成), born in Yinshang county in Fuyang, Anhui, in 1965. He came to Shaolin Temple in 1981 and became a disciple of abbot Shi Xingzheng (释行正), who passed away in 1987. Shi Yongxin then followed in his footsteps and managed the temple affairs. He formally became head monk in 1999.

Moreover, Shi Yongxin reportedly served as President of the Henan Provincial Buddhist Association since 1998 and as Vice President of the Buddhist Association of China since 2002.

Shi Yongxin, photos via Weibo.

Shi Yongxin was thus an incredibly powerful figure—not only because of the decades he spent overseeing temple affairs, but also due to his influence within public, institutional, and religious spheres.

Holding such a visible role, Shi Yongxin (释永信) also had (or has—though it’s unlikely he’ll ever post again) a Weibo account with over 882,000 followers (@释永信师父). His last post, made on July 24, was a Buddhist text about the ‘Pure Land’ (净土)—a realm said to make the path toward enlightenment easier.

That post has since attracted hundreds of replies. While some devoted followers express disbelief over the scandal, many others respond with cynicism, questioning whether anything about Buddhism remains truly ‘pure.’

One widely shared post shows an artist sitting in front of a painting of Shi Yongxin, writing, “Worked on this painting for six months, just finished late last night—feels like the sky’s collapsed.” The second picture, posted by someone else, says, “Just change it a bit.”

One aspect of the scandal fueling online discussions is the fact that Shi Yongxin had led the monastery for so long. Rumors about his “chaotic private life” and unethical behavior surfaced years ago, going back to at least 2015 (#释永信10年前就曾被举报私生活混乱#; #释永信曾被举报向弟子索要供养钱#). One of the questions now echoing across social media is: why wasn’t he held accountable sooner? “Who was protecting him?”

“The Tip of the Iceberg”

The Shi Yongxin scandal does not just hurt the reputation and cultural brand of the Shaolin Monastery; it also damages a certain image of Buddhist monks as a collective of people with true faith and integrity.

According to well-known knowledge blogger Pingyuan Gongzi Zhao Sheng (@平原公子赵胜), many people’s understanding of abbots or Buddhist masters (“方丈大师们”) is flawed, since it’s generally believed they attained their high positions within the monasteries due to their moral virtue or deep understanding of Buddhism. In reality, Zhao Sheng argues, these individuals often rise to power because they are skilled at earning money and gaining influence.

“To put it bluntly,” Zhao Sheng writes, “temples have been places of deception, corruption, opportunism, and exploitation since ancient times.”

The blogger argues that much of the influence and power of Buddhist masters was stripped away under Mao Zedong, but that some new famous monks rose in the 1980s, using their skills and connections to rebuild temples and turn them into thriving enterprises.

“If you want to find a few people in temples who truly have faith, who truly have personal integrity, and who are truly dedicated to saving all living things, it’s not that they don’t exist—but it’s rather difficult, like finding a needle in a haystack,” Zhao Sheng wrote.

Some commenters suggest that Shi Yongxin is just the tip of the iceberg (“冰山一角”). They believe that if someone as influential as him can be involved in such misconduct—despite whistleblowers having tried to expose him for over a decade—there must be many more cases of power abuse and corruption within China’s monasteries.

“I previously donated money to the temple,” one commenter on Xiaohongshu wrote: “Although it wasn’t much, it does make me a bit uncomfortable now.”

Another person posted that the Shi Yongxin scandal gave them a sense of despair.

Some older posts about the extravagant lifestyles of head monks — including their luxury cars — have also resurfaced online and are once again making the rounds, suggesting that netizens are actively revisiting other potential instances of misconduct within the monastic world.

Abbot Guangquan Fashi (光泉法师) with a Ferrari California T, Kaihao Fashi (开豪法师) with a Porsche Panamera, Shi Yongxin (释永信) linked to an Audi Q7, and Huiqing (慧庆) and a BMW 7 Series.

One image that resurfaced online shows Shi Yongxin—allegedly driving an Audi Q7—alongside other abbots, such as Guangquan Fashi (光泉法师), the head monk of Lingyin Temple (灵隐寺), who is associated with a Ferrari.

More images like these are now circulating, as people delve into the ‘secret lives of monks’ beyond the spiritual, shifting focus to their material lives instead.

Monks from major temples, including Qin Shangshi (钦尚师) of Famen Temple, E’erdeni (鄂尔德尼) of Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, Yin Le (印乐) of Baima Temple, and Huiqing (慧庆) of Baishou Temple, are rumored to be associated with high-end cars like BMWs, a Porsche Cayenne, and a Range Rover.

While the results of the investigation into Shi Yongxin are still pending, many netizens are already looking beyond him. One person writes: “Are you realizing now? It’s not just Shaolin Temple that has money, other temples aren’t exactly short on money either.”

Another person wonders: “Are the monks in today’s temples actually still truly devoted to spiritual practice at all?”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Waiting for Karma in the Maskpark Scandal

The Secret Life of Monks: Shi Yongxin’s Shaolin Scandal Casts a Shadow on Monastic Integrity

Six Chinese Students Dead After Falling Into Flotation Tank During Mine Visit

Something In the Water: How Yuhang’s Smelly Water Went from Odor Incident to Trust Crisis

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

Behind the Mysterious Death of Chinese Internet Celebrity Cat Wukong

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

Earring Gate: Huang Yangdiantian and the 2.3 Million RMB Emerald Earrings

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

10 Viral Chinese Phrases You Didn’t Know Came From Video Games

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral3 weeks ago

China Memes & Viral3 weeks agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature9 months ago

China Books & Literature9 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Society10 months ago

China Society10 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World12 months ago

China World12 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media