The Many Layers Behind the “Sister Hong Incident”

Published

3 months agoon

Dear Reader,

A 60-year-old man from Nanjing became the biggest trending topic on Weibo recently after news circulated that he had cross-dressed as a woman, lured 1691 men into having sex with him, recorded the encounters, and then spread the videos online. It was suggested that he had exposed the men to HIV and infected at least eleven of them.

That particular story turned out to be inaccurate, but the real story behind the sensationalism was strange enough to pique the interest of countless netizens.

The actual case involves a much younger man: the 38-year-old Mr. Jiao who pretended to be a woman and arranged to hook up with many men, secretly recording the encounters and uploading the footage online.

The story first began circulating online in early July. It went viral across multiple Chinese social media platforms after local police arrested the man and publicly announced the case (likely also due to the rapid spread of sensationalized rumors).

This is what the police report of July 8 said:

Police notification

Recently, Jiangning police received reports from members of the public stating that their private videos had been disseminated online by others. Jiangning police immediately launched an investigation and, on July 5, arrested the suspect Jiao (焦) X.

Upon investigation, it was found that Jiao X. (male, 38 years old, person from outside the province) impersonated a woman, arranged to engage in sexual activities with multiple men, and secretly filmed the encounters to disseminate the videos online.

The widely spread online rumor that “a 60-year-old man in Nanjing dressed as a woman and had intimate relations with over a thousand people” is false.

On July 6, Jiao X. was criminally detained by Jiangning police in accordance with the law on suspicion of the crime of disseminating obscene materials. The case is currently under further investigation.

Jiangning Branch of the Nanjing Public Security Bureau

July 8, 2025

By now, the case has come to be known as the “Nanjing Old Guy Hong Incident” (南京红老头事件).

In Chinese, “Hong” (红) means “red,” which is not only a color but also carries connotations of celebrity or notoriety in this context.

Jiao initially used the online nickname Ah Hong (阿红). This nickname soon evolved into “Nanjing Sister Hong” (南京红姐), but was later changed by netizens to “Nanjing Old Guy Hong” (南京红老头) after some argued it was inappropriate to refer to Jiao as a woman. Official media posts calling Jiao “Sister” received hundreds of angry reactions, with people demanding an end to the use of the female title.

Jiao had reportedly posed as a woman for a long time, using various social platforms—from WeChat and QQ to Momo—to find men to hook up with.

He wore women’s clothing, a long wig, used heavy white make-up, and also relied on beauty filters and voice-changing tools to appear and sound more feminine to the men he met online.

Since Jiao didn’t charge any money for these encounters, some of the men apparently thought it polite to bring gifts. Leaked footage shows visitors arriving at his apartment with small offerings—from fruit and milk to half-full bottles of cooking oil.

Jiao had secretly set up a hidden camera in the rooms to capture the sexual encounters, and later spread these online through online groups where participants had to pay a membership fee of 150 yuan (US$21) per person to join the group.

Some of Jiao’s victims reported him to the police after discovering that videos of their encounters were being circulated online—allegedly after they were recognized by others. By now, several men have been identified by people who know them, and one woman reportedly recognized her own husband in one of the videos.

The exact number of men Jiao met and secretly filmed remains unknown. While authorities have dismissed the viral claim of over 1600 men as exaggerated (a number reportedly mentioned by Jiao himself), they have not released an official count, and the investigation is still ongoing.

The videos have since spread widely online, showing Jiao engaging in various forms of sexual activity with different male partners. While it’s unclear how many of the men initially believed he was a woman, it seems highly likely—if not inevitable—that many realized the truth at some point during the encounters.

Social media discussions around the case now touch on a range of issues, from privacy violations to gender identity and public health concerns.

🏛️ Legal Implications: From Violating Privacy to Endangering Public Health

First, the legal aspects of the case are drawing significant attention, with various lawyers and legal experts weighing in on what crimes Jiao may have committed. For now, he is under criminal detention for disseminating obscene materials—the production, distribution, and sale of sexually explicit content is illegal under Chinese law.

But Jiao also violated the privacy and portrait rights of others by sharing explicit videos that clearly show their faces without consent.

And what if Jiao is indeed HIV-positive and knowingly engaged in unprotected sex?

According to Legal Daily (法治日报), he could then be charged with “endangering public safety through dangerous means” (“以危险方法危害公共安全罪”).

This offense carries a sentence of 3 to 10 years in prison if no serious harm occurs, but if it results in severe injury, death, or major damage, it could lead to life imprisonment or even the death penalty.

On the morning of July 8, a local CDC official confirmed that health authorities were now involved in the case. While Jiao’s health status is considered private, officials said they’ll share updates if and when it’s appropriate.

💥 Social Shock: Public Health and “Hole-Sexuals”

There has also been significant social shock over the story. The footage that’s been circulating online shows dozens of different men visiting Jiao — from student types and businessmen to men from all walks of life, including fitness trainers, married men, college athletes, and also young foreign men.

Many netizens expressed that the story changed the way they view the people around them. The men visiting Jiao were not some ‘basket of deplorables’ — they included wealthy older men, young and attractive guys, educated tech professionals. That realization unsettled many, shaking their worldview on multiple levels.

Although this triggered many jokes, it also raised uncomfortable questions not just about how little people may know their friends, neighbors, or even romantic partners—but also about public health. If Jiao did pose an HIV risk, it means these men—many of whom are married or have families—may have unknowingly brought that risk home with them after these unprotected encounters arranged online.

Chinese commentators and bloggers therefore tied the case to women’s sexual health, suggesting that a significant number of gynecological infections among married women are actually caused by their own husbands.

There were multiple online posts suggesting that the entire story reflected the sexual repression experienced by many Chinese men. Jiao, as a man himself, may have understood male psychology well — and was simply giving these men the emotional and physical attention they were lacking at a time when their sexual needs were not being met.

Some argued that such situations are a byproduct of the crackdown on KTV bars and massage parlors, hinting at the shrinking space for illegal prostitution in mainland China.

“Sometimes it really feels like heterosexuality is a joke,” blogger Chen Shishi (@陈折折) wrote: “These men are so filthy, and yet they go back and pretend to be good boyfriends, good husbands, good fathers, good men.”

She added: “As long as there’s a hole, they’re in.”

In doing so, Chen used the term 洞性恋 (dòngxìngliàn), a satirical play on the Chinese word for “homosexual” (同性恋, tóngxìngliàn, literally “same-sex love”).

By replacing the first character 同 (“same”) with 洞 (meaning “hole”), the term becomes “hole-sexual” instead of “homosexual,” mocking those men who sought out Jiao without caring what “she” looked like — or even whether she was secretly a man — as long as there was a “hole” to satisfy them. Recently, 洞性恋 (dòngxìngliàn) has been used a lot by Chinese netizens commenting on this case.

🛑 Politically Sensitive: Controlling the Narrative

Apart from the criminal charges Jiao may face, this story inevitably has some deeper layers that are politically sensitive and are therefore flattened and rewritten into safer territories.

Chinese well-known blogger Lu Shihan (@卢诗翰) recently commented on this issue on Weibo and Zhihu, critiquing how Chinese media and public discourse have framed this story. According to Lu, the narrative was intentionally shifted away from any discussion of a possibly trans, marginalized sex worker.

Lu suggests that censorship, social discomfort, and political sensitivity around class struggles and LGBTQ+ issues force both media and the public to stick to the safest possible framing.

That “safe narrative” is a comical and odd case about a ridiculous old man in a wig, crossdressing for his own fetish pleasure and spreading obscenity, scamming straight men into a sex scandal.

Acknowledging that many of the men may have known (or didn’t care) that “Nanjing Sister Hong” was biologically male would turn the incident into a conversation about queer identity and sexuality. And as Lu points out, that’s a no-go zone.

In his commentary on the issue, Lu Shihan mentions the story of another “Sister Hong” (红姐), an older street sex worker who became well-known in Shenzhen’s Sanhe district and even gained some online fame at a national level.

“Sanhe Sister Hong” came from a mountainous village and ran away as a teenager to work in the city. After being abused and abandoned, she fell into homelessness and eventually turned to sex work to survive in Sanhe, a place known for its lower-class young (post-1990) male day laborers who hop from job to job, self-precariously calling themselves the “great gods of Sanhe” (三和大神).

In this environment, Sister Hong stood out not just as a sex worker but also as a vagabond woman, and she has almost reached cult-like status for some—she’s now known as the legendary Sister Hong.

“Nanjing Sister Hong” ultimately got that nickname because of the “Sanhe Sister Hong.”

Lu argues that around China, from Nanjing to Shenzhen to Guangdong, there are many “Sister Hongs,” and their vulnerable position, marginalization, and methods of income have to do with much deeper issues about gender and class struggles that go beyond some clueless straight men who just happen to stumble into their bedrooms.

On Chinese Q&A site Zhihu, some commenters are convinced that Jiao’s ‘customers’ were very well aware that he was not a woman — but that it is common to see men dressing up as women for a certain group of closeted men who feel more at ease in ambiguous, feminized encounters that don’t directly confront their own sexual identities. Also, for them, people like Sister Hong feel like safer territory.

🎭 Cultural Fascination: The Story of Shi Peipu

At the heart of this story also lies a deeper cultural fascination: the image of a male figure assuming a female persona to seduce other men — and the taboo topics that come with it. Cross-dressing has a long history in China, from traditional opera to contemporary media.

Some netizens — somewhat jokingly — compared “Sister Hong” (Jiao) to the case of Shi Peipu (时佩璞), a story that inspired the award-winning play M. Butterfly (1988) by David Hwang.

Shi Peipu (1938–2009) was a male Chinese opera singer who pretended to be a biological woman for over two decades. Shi Peipu worked for the Chinese secret service and was involved in what has been called one of the “strangest cases in international espionage.”

Shi Peipu was originally from Kunming and moved to Beijing in the 1960s. The then 26-year-old Shi met the French diplomat Bernard Bouriscot (布尔西, 1944) at a Christmas party in 1964, where Shi came dressed as a man.

Shi told Bouriscot that he was actually a female opera singer who had been forced by his father to present himself as a man because he desired a son so much. Bouriscot believed it, and their love affair took off — a romance that also continued when Bouriscot was stationed abroad.

For a period of twenty years, Shi pretended to be a woman during this ‘love relationship’ in order to gather intelligence information from Bouriscot.

Shi went to extreme measures to keep the Frenchman close to him, as ‘she’ even convinced Bouriscot that she had become pregnant with his child in 1965, just before the two would be apart for a long time. Shi adopted a boy from Xinjiang and presented him as their alleged child, which Bouriscot apparently believed.

In 1982, Shi and Bouriscot moved to Paris, where they were both arrested a year later — Shi’s secret allegedly finally came to light when the CIA informed the French government that secret information from the French Embassy in China had leaked during the 1970s.

Even when the police burst into their home to arrest them, the Frenchman allegedly still believed Peipu was his wife and the mother of his child. It took a medical report for him to realize the truth.

Bouriscot attempted suicide when he discovered that Shi was actually a man. He was convicted of espionage — news that made it to the front pages in France — and both men were sentenced to six years in prison (although both got out earlier).

Shi, who did not plead guilty to being a spy, passed away in Paris in 2009. About the affair, Bouriscot later said: “When I believed it, it was a beautiful story.”

Shi Peipu’s story has become one of those famous stories that is still discussed online and pops up every now and then — such as in the discussions talking about “Sister Hong.” Because the story is so bizarre, it is mostly discussed in certain frameworks that hardly challenge dominant ideas about gender and sexuality.

📌 So what’s the takeaway in the “Sister Hong” case? On the surface, it serves as a cautionary tale about meeting strangers online and the potential nightmare of seeing yourself butt-naked on the internet.

But more deeply, the reason this case shook the Chinese internet is because it points to something much larger. It touches on issues that usually remain hidden beneath the surface. It reveals vulnerability on all sides.

The vulnerability of people like “Nanjing Sister Hong” — whether cross-dressing or identifying as transgender, they are operating outside the gender binary. As research by scholars like Eileen Yuk-ha Tsang shows, individuals in this position often face intense social stigma, family rejection, discrimination, severe depression, and abuse by intimate partners (many of whom present as heterosexual men). While none of this excuses Jiao’s actions — secretly recording hundreds of men and exposing their faces and literal private parts online — it does shed light on some of the dynamics that may have pushed him into the internet’s darkest corners.

There’s also the vulnerability of the men who were filmed — now watching their lives collapse as their identities are exposed to the public.

And then there’s the vulnerability of the wives and partners at home, not only discovering their partners’ infidelity in the most public way possible, but also having to face the emotional and physical consequences it may carry for their own lives and health.

For now, the “Nanjing Sister Hong” case is already among the most-discussed topics on Chinese social media this year. It has become the source of countless memes and AI-generated parodies. The story got so big that people are now joking even Trump was one of his secret visitors (see AI meme).

There are even memes about the “Sister Hong starter kit” and others mocking the man who brought half a bottle of cooking oil.

Some joked that “Sister Hong” bears an uncanny resemblance to well-known Chinese political commentator Hu Xijin.

These jokes probably won’t help anyone much, but they’re an inevitable product of China’s meme machine. Still, they shine a bit of light on a topic of which many sides will inevitably remain in the dark for a long time to come.

Scroll down for more highlights of what’s been trending and noteworthy lately. (This is a long newsletter, so make sure to click through to read the full edition — including the controversy over a Chinese student expelled for a fling with a Ukrainian esports player.) A special thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping put together this edition.

I’m happy to see more requests coming in for group subscriptions. Are you reading What’s on Weibo at work? Group subscriptions are available at a discount for 10, 15, or 20 people. Let the person in charge of media or publication subscriptions know that subscribing to What’s on Weibo is a smart move for making sense of what’s trending in China (and that this is a 100% independent, reader-supported platform!) 🚀

Thanks, as always, for reading and for your support. And if there’s a topic you want to know more about, or something you think I should include—don’t hesitate to reach out.

Best,

Manya

PS I mentioned Eileen Yuk-ha Tsang here as one of the scholars focusing on Chinese transgender sex workers. Coincidentally, her new book Unlocking the Red Closet: Gay Male Sex Workers in China is coming out on July 29.

What’s Trending

Popular Topics at a Glance

Another major story that’s been trending involves a 31-year-old captain from Jilin working for China Southern Airlines, who reportedly stabbed two of his colleagues after a work-related dispute before jumping to his death from a high-rise building in Changchun in early July. His colleagues survived the attack.

This latest tragedy has sparked renewed discussion about the intense pressure faced by commercial pilots in China. Many pilots are locked into rigid, high-penalty contracts that make it financially difficult to leave their position at the company while struggling to go up in rank. Even when demoted or given fewer flight hours, they may feel unable to walk away—conditions that can severely impact mental health.

The 31-year-old captain from Jilin, named Li Xing, reportedly spiraled after failing a competency evaluation that disqualified him from flying. Some netizens remarked on the irony of how strict standards intended to guarantee flight safety may, in fact, also put more pressure on pilots and become risk factors that trigger accidents.

The incident, together with the recent Air India Flight 171 crash, has stirred public memory of the China Eastern Airlines MU5735 crash three years ago—an investigation that never reached an official conclusion, though many believe it was also a case of pilot suicide.

China’s Wahaha Group (娃哈哈集团) is once again in the spotlight this week — and not for good reasons. The head of the company, one of the largest food and beverage producers in China, is currently being sued by her presumed siblings over the enormous inheritance of their late father.

Wahaha has long been a beloved brand in China. When founder and chairman Zong Qinghou (宗庆后) passed away in March last year, many people showed their sympathy for the brand — and for Zong, who was seen as a patriotic and humble businessman — by buying Wahaha mineral water.

But since the company was taken over by Zong’s daughter, Zong Fuli (宗馥莉), things haven’t been running quite the same. Public sentiment has already been shifting, especially earlier this year when netizens discovered that the Wahaha water they purchased was actually produced by the cheaper brand Jinmailang (今麦郎).

The ongoing inheritance scandal is further damaging Wahaha’s public image — particularly because it involves Zong Qinghou’s three alleged illegitimate children, all of whom hold U.S. citizenship.

Last year, Wahaha was praised by netizens for being a patriotic brand, while its main competitor, Nongfu Spring, was accused of being unpatriotic — partly because its CEO’s son, Zhong Shuzi (钟墅子), also holds an American passport. That sparked online debate about corporate loyalty to China.

Now that it turns out Zong Qinghou has not one but three children in the U.S., together with former Wahaha senior executive Du Jianying (杜建英), public perception of both the brand and Zong’s legacy is starting to shift.

At the same time, this case offers a fascinating glimpse into the inner dynamics of one of China’s most iconic companies — and it’s definitely a topic that Chinese netizens will be closely following for some time to come (and so will we).

“Hot hot hot hot hot hot hot week ahead” (#未一周热热热热热热热#), was the hashtag pushed by Chinese state media this week, as large parts of the country brace for temperatures above 35°C (95°F) in the days to come.

In regions stretching from Shaanxi to Guizhou, highs are expected to reach 37–39°C (98.6–102.2°F), with some areas soaring past 40°C (104°F). Already, nine provinces and regions—including Xinjiang, Shanxi, Hubei, Hunan, Sichuan, Chongqing, Anhui, Jiangsu, and Jiangxi—have reported nighttime lows above 30°C (86°F).

The heatwave in Xinjiang has drawn particular attention online, with daytime temperatures in places like Turpan consistently exceeding 40°C (104°F).

What’s Noteworthy

Small news with big impact

This week, you also need to know the story of 21-year-old Chinese student Li, who was expelled by Dalian Polytechnic University (大连工业大学) for sleeping with Ukrainian e-sports player Danylo Teslenko—known online as ‘Zeus‘ —on the grounds of “harming national dignity.” The case has triggered a massive online debate, with people weighing in from all sides.

The 37-year-old Ukrainian man had shared some intimate footage of their encounter online—content that showed the two in a hotel room, clearly fond of each other, though not sexually explicit. Li, reportedly a fan, had allegedly flown to Shanghai to meet him during his “Asia tour” in December 2024.

The footage soon went viral on Douyin and beyond, leading to Li being doxxed and harassed. She was criticized for allegedly cheating on her boyfriend and for sleeping with a foreigner. Zeus eventually deleted the video once he realized the seriousness of the backlash.

Although the incident took place months ago, it only hit the top of trending lists this week—after the university’s decision to expel her became public. On July 8, the school posted the expulsion notice on its website, naming Li in full and claiming she had already been informed of their decision back in April 2025.

But for what, exactly? That’s the question at the heart of the controversy. People have combed through school regulations, and it’s still unclear which specific rule Li actually broke by having an intimate relationship with a foreigner.

“Huh? Being sexually open can be a reason for expulsion now? And the video wasn’t even uploaded by the girl herself,” one commenter wrote.

Many believe this case is about gender dynamics—and that a male student wouldn’t have faced the same consequences for sleeping with a foreign woman.

Although there are some who condemned Li for bringing shame upon her school and country, the majority view her as a victim on multiple levels. Zeus should never have posted private footage online. The university had no cause to expel or publicly shame her, and online harassment from netizens was unjustified.

Somewhat unexpectedly, prominent Chinese commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) has spoken out in her defense, arguing that it was Zeus who embarrassed Ukraine by uploading intimate footage—not Li who brought disgrace to China. He also questioned whether expelling a young woman and pushing her out into society was a proportionate or fair decision.

Li still has time to appeal the university’s decision—but whether she will remains unclear.

What’s On

Handpicked China events for our readers

In the last newsletter, I announced our new events page that keeps track of upcoming, insightful China events happening around the world. The page highlights talks, panels, and lectures covering everything from China’s (digital) culture and society to history, language, and broader geopolitical insights — with a particular focus on events that are accessible virtually.

Some events to look out for this month:

- July 24 (Livestreamed): “Chinese Views of the Indo-Pacific Strategy Part of the GIGA China Series, this session examines how Chinese policy experts perceive the Indo-Pacific concept — often seen as a strategy to contain China. While some analysts stress fears of a unified anti-China alliance, others point to strategic diversity among Indo-Pacific actors. Speakers Jérôme Doyon and Mathieu Duchâtel explore how China might respond, from shaping regional narratives to employing wedge strategies. Link.

- July 29 (livestreamed) “Shifting Currents: U.S.–China Economic Policy in Transition”

Hosted by Asia Society Northern California, this event gathers academic and policy experts to discuss recent shifts in U.S. economic policy and their implications for China. The panel will explore trade, geopolitics, and the evolving dynamics of the bilateral relationship.. Link. - July 29/30 (depending on your timezone) (Livestreamed): “US-China Relations and the Chinese American Experience”

Organized by the California Alumni Association Chinese Chapter, this talk features Professor Harvey Dong (UC Berkeley) and traces the influence of two centuries of US–China relations on Chinese American communities. From the Opium Wars to the Cold War and beyond, this session offers a timely perspective on diplomacy, migration, and racialization. Link.

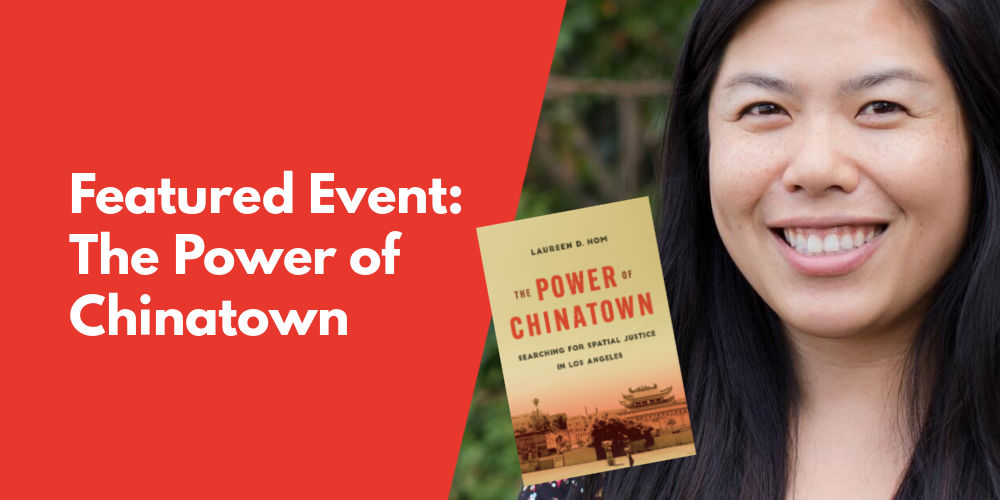

Another event that is not livestreamed but taking place at the CHSA Museum in San Francisco on July 26 is a talk by author Laureen D. Hom about The Power of Chinatown. This is the title of her most recent book, in which she explores the tensions between economic development and cultural preservation. Through stories from residents, activists, and business owners, Hom zooms in on L.A.’s Chinatown as a contested site of cultural identity, political struggle, and urban development. Link.

Since this list is manually curated, please do send in any events you think suit the list and interests of What’s on Weibo readers.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed the last newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know. No longer wish to receive these newsletters? You can unsubscribe at any time while remaining a premium member.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Memes & Viral

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From a tragic “wild child” case in Yunnan to the farewell of Nobel laureate Yang Chen-Ning, here’s what’s trending on Weibo and beyond this week across Chinese social media.

Published

2 days agoon

October 19, 2025

🔥What’s Trending in China This Week (Week 42, 2025)? Stay updated with China Trend Watch by What’s on Weibo — your quick overview of what’s trending on Weibo and across other Chinese social media.

1. “Wild Child” from Yunnan Sparks Concern and Investigation

Screenshots circulating on Chinese social media showing the “wild child” in Yunnan.

A tragic and widely discussed story from Yunnan has been trending on Weibo this week, centering on a 3-year-old boy from Nanjian County who was spotted near a highway service area — naked, neglected, and walking on all fours. Online videos led Chinese netizens to dub him the “feral child.”

There have been conflicting media reports on the case over the past few days. From The First Scene (@第一现场) to Shanghai Reporter (上观新闻) some claimed the child’s parents are impoverished and jobless while others reported the father and mother are actually highly educated and do have resources, but that the choice to raise their child like this is related to lifestyle philosophy. The parents reportedly insisted that the child used to suffer from eczema and found clothes irritating and painful, so “he doesn’t like wearing clothes.”

One thing that local villagers quoted in these reports agree on is that the situation is “not normal.” The child, who never wears clothing, allegedly mimics animal behavior and refuses to eat from his hands — preferring to eat food off the ground. Locals previously already villagers reported the situation to the police.

Authorities in Nanjian County have announced the creation of a special task force to investigate this case. Officials said no signs of human trafficking were found, and that the parents are currently outside Yunnan Province. According to Beijing Youth Daily, The child and his parents are now under supervision, although it is not clear what this actually means – since other sources say the parents are not willing to cooperate. They also have another boy, who is currently one year old. Authorities have also investigating whether the parents’ behavior constitutes a crime.

Manya’s Take:

The “wild child” story brings back memories of the Xuzhou mother of eight. That heartbreaking case also gained national attention after netizens shared a video showing a woman chained up in a shed next to her family home. The chaotic media coverage of that case mirrors what we’re seeing now: media outlets are quick to jump on the story, while local authorities — feeling public anger and pressure — rush to investigate, resulting in conflicting reports, rumors, and fake news. Both situations involve rural counties that would otherwise hardly ever make headlines, with local authorities often unequipped to handle such crises quickly. Hopefully, there will be a clearer update on this story soon.

2. China Responds to Trump’s Remarks on Soybean Trade and Cooking Oil

Soybeans have been trending this week. As China is boycotting American soybeans – the fourth most sold agricultural product from the country – farmers in the US are facing uncertain times, as it’s harvesting season and the biggest purchaser of soybean exports is China.

On Tuesday, Trump wrote on Truth Social that China was “deliberately halting U.S. soybean imports,” calling it an “economically hostile act.” He also threatened to terminate business with China regarding cooking oil and other areas of trade as retribution.

On Chinese social media, people seemed unimpressed. The term TACO is also seen more often, a popular abbreviation for “Trump Always Chickens Out.” The Foreign Ministry dismissed Trump’s claims as “unfounded” and emphasized China’s commitment to normal trade relations. On Weibo, commentator Hu Xijin wrote: “Haha, so he [Trump] slaps tariffs on China and blocks chip exports and that’s not considered ‘hostile’? But when China doesn’t buy soybeans, suddenly it is? What kind of logic is that!”

Manya’s Take:

Chinese netizens are treating this latest trade exchange with irony rather than outrage, not only viewing it as a sign of US inconsistency on trade but also there’s some banter about the ‘cooking oil’ threat: when the US side talks about banning imports of “Chinese cooking oil” many assume they meant edible oil (食用油), while what the US actually imports from China is used cooking oil (UCO, 废食用油/地沟油) — waste oil that’s recycled to make biofuels. So the joke is that even Trump himself is seemingly mixing up cooking oil and used cooking oil, moreover threatening a ban that would hurt itself more than China, turning this trade spat into a moment of internet humor.

3. Nanjing Deji Plaza Faces Backlash Over VIP-Only Restrooms

The exclusive members-only restroom at Nanjing’s Deji Plaza.

Nanjing’s luxury shopping mall Deji Plaza (德基广场) has sparked controversy after introducing members-only restrooms accessible exclusively to VIP members (天象会员) who spend over 200,000 yuan ($28,000) annually. Access requires scanning a Deji membership QR code.

Beyond offering peace and privacy, the restrooms feature Tom Ford vanity sets, Jo Malone handwash, and Dyson hairdryers. One Xiaohongshu blogger (and VIP member) noted, “The maintenance cost here is ten times that of a regular restroom.”

After news of the VIP restrooms went viral, it fueled debate about turning ‘a basic human need’ into a ‘class privilege’ or “privatizing a public facility.” One user commented, “Now even restrooms have to reflect the wealth gap?”

Despite the criticism, curiosity grew — many users purchased “code-scanning services” on secondhand platforms to gain access, quickly undermining the restroom’s exclusivity. In response to the controversy, Deji Plaza stated that the members-only restrooms would soon be dismantled and converted into a regular public facility. Regardless, and despite the backlash, the initiative seems to have been fruitful in terms of brand name recognition, as it got everyone talking about Deji Plaza.

Manya’s Take:

There’s some irony in this story: there’s controversy over a mall toilet being “VIP,” yet at the same time, it’s the exclusivity that makes people want to try it. According to the latest posts on Xiaohongshu (XHS) by Deji Mall visitors, the VIP toilets are already gone, and people are back to complaining about the restrooms being too crowded and dirty. One XHS commenter (西蒙吴) had the best take on the issue: in a time when Chinese media are working to downplay the country’s wealth gap and ease public resentment, Deji Mall made the right move by dismantling the card-access VIP toilets — if not for the pressure of online public opinion, authorities might have stepped in themselves. It was an unwise move simply because it was all about a toilet: unlike VIP waiting areas or service counters, consumers don’t like restrooms being divided by class. A smarter approach would have been to create a VIP lounge that just happens to include a restroom.

4. Arc’teryx Responds to Tibet Fireworks Show Environmental Damage Investigation

The controversial fireworks show held in Tibet on September 19.

This is a topic that has sparked outrage and continued discussion in China over the past weeks. On September 19, a major fireworks event was held at an altitude of around 5,500 m or 18,000 feet in Tibet’s Himalayas, created by famous Chinese artist Cai Guoqiang (蔡国强) and sponsored by the outdoor brand Arc’teryx.

The 52-second show, titled “Ascending Dragon” (升龙) was supposed to impress people for its spectacular and colorful use of 1,050 fireworks, but it triggered outrage instead: critics blasted it as tone-deaf commercialization and ecological abuse of sacred and fragile land, and soon an investigation was launched.

Now, the outcome of that investigation has also become a major talking point as it revealed disturbance to local wildlife and caused significant environmental damage of over 30 hectares of grassland.

Cai Guoqiang and his studio will be held legally accountable for environmental damage, and Arc’teryx, as a sponsor of the event, will also bear legal responsibilities. Furthermore, the relevant county officials who had initially approved the show without going through the proper channels are also punished: Party Secretary Chen Hao (陈浩) has been dismissed, and nine other county officials received formal penalties ranging from removal to warnings.

Manya’s Take:

A lot has already been said and written about this controversy. What it comes down to, in the public perception in China, is that the high ambitions and personal goals of the artist and the Arc’teryx brand — which built its image around environmental responsibility and authentic outdoor culture — were pursued at the expense of Tibet’s fragile environment and marginalized communities. Their so-called “dreamlike” event left lasting scars for a fleeting 52-second spectacle. More than just serving as a warning for brands to ensure their actions align with their “eco-friendly” promises, this entire case will undoubtedly go down in history as a moment of awareness — a case study for future art events and large-scale performances in nature in China — on what not to do, and on how to balance spectacle with responsibility.

5. Nobel Laureate Yang Chen-ning Passes Away at 103

Yang Chen-ning passed at the age of 103.

The death of the renowned Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), also known internationally as Chen-Ning Yang, China’s first Nobel laureate in physics, has been trending across Weibo, Douyin, Zhihu, and Toutiao in recent days. Yang passed away in Beijing on October 18, 2025, at the age of 103, just weeks after celebrating his birthday on October 1.

On social media, Yang is remembered as a legendary physicist who devoted his life to science and truth. He shared the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics with Li Zhengdao (李政道) for discovering parity violation in weak interactions, and co-developed the Yang–Mills theory with Robert Mills in 1954, a cornerstone of modern particle physics.

Many online tributes also recall Yang’s lifelong friendship with nuclear physicist Deng Jiaxian (邓稼先, 1924–1986). The two met in middle school and went on to become giants of Chinese science. Yang’s wife, Weng Fan (翁帆), has also become part of the online remembrances. Over 50 years his junior, she met Yang while she was a student; they married when she was 28 and he was 82. Her tribute to Yang, expressing gratitude for having shared his company for many years, has received over 140 million views on Weibo.

Manya’s Take:

There is certainly a strong sense of national pride in the accomplishments of Yang Chen-Ning, but on social media, much of the attention also centers on his relationship with his wife, who was 54 years younger. Many see Yang’s passing as a moment of reflection — was she there for the money and fame, or for love? Opinions are divided, but the fact remains that the two were married for over twenty years, and she stayed by his side throughout. Some argue that Yang was simply so extraordinary, in both mind and body, that he naturally connected with younger people — and they with him. Others say their love was “timeless,” that true soulmates (灵魂伴侣) do not see age. Either way, it’s clear that 2025 netizens aren’t all cynics — there are quite a few romantics out there.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Travel

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Did tents defeat China’s hotel industry during the National Day holiday?

Published

6 days agoon

October 15, 2025

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Now that China’s combined National Day and Mid-Autumn Festival holiday (国庆 + 中秋) has ended, social media has seen a surge in discussions about major 2025 travel trends. According to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, a lucky total of 888 million domestic trips were made during the eight-day holiday.

While many Chinese cities and regions focused on offering innovative experiences — from lantern festivals to street performances — to attract travelers, there was also a grassroots trend that stood out.

Especially among the 18-35 age group, more Chinese are now choosing tents over hotels. On October 10, Business Times China (财经时报) featured an article about how ‘tents’ are putting a ‘dent’ into China’s hotel industry (title: “Did Tents Defeat the Hotel Industry during the National Day Holiday? 这个十一假期,打败酒店行业的是帐篷”).

Over recent years, as domestic travel has boomed, hotel prices in China have skyrocketed during holiday periods, with rates often doubling or tripling. For many—particularly younger travelers—this has made trips less affordable and less worthwhile. (Average nightly prices for mid- to high-end hotels in major cities exceeded 800 RMB / $112 this season.)

So what are we seeing now?

🔸 People are looking for alternative overnight stays, even though some hotels have lowered their prices in light of disappointing bookings.

🔸 Bathhouses are one example: many bathhouses or spas in China have become all-in-one leisure complexes combining hot springs, saunas, massages, dining, entertainment, and overnight lodging—becoming a new competitor for hotels (dubbed 洗浴旅游, “bathhouse tourism”).

Luxury bathhouses aren often opened 24/7 and have come a popular destination among young travelers.

🔸 Tents are growing in popularity. The outdoor equipment industry is seeing explosive growth in China, and Business Times China connects this growth to consumer backlash against unreasonable prices and poor service in Chinese hotels, seeing a future for more luxury camping models.

🔸 But it’s not just luxury camping. Many netizens across China have shared videos of travelers setting up tents and sleeping outdoors by roadsides or in scenic spots. Not only are people enthusiastic about outdoor camping and the experience itself, they also see it as a “consumption awakening” (消费觉醒), where younger generations are not willing to blindly pay ten times more for one night in a hotel than the purchase of a tent.

🔸 Another term that has been popping up more frequently is “Tangping Travel” (躺平式旅游). Tangping means “lying flat,” a phrase often used by young Chinese who “lie flat” as a way to cope with social pressure and competitive stress (read more). Unlike previous travel trends, where “special forces travelers” would rush to clock in at as many destinations as possible in a short time, tangping travel — whether in bathhouses, hotels, or tents — is about doing as little as possible, reflecting a shift away from hectic travel schedules.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

House of Wahaha: Zong Fuli Resigns

How the “Nexperia Incident” Became a Mirror of China–Europe Tensions

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Rising Online Movement for Smoke-Free Public Spaces in China

China Trend Watch: Pagoda Fruit Backlash, Tiananmen Parade Drill & Alipay Outage (Aug 11–12)

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral3 months ago

China Memes & Viral3 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature12 months ago

China Books & Literature12 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral10 months ago

China Memes & Viral10 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained