Newsletter

The 315 Gala: A Night of Scandals, A Year of Distrust

From sanitary pads to shrimp: these were 315 Gala’s biggest scandals. It’s business as usual.

Published

11 months agoon

Dear Reader,

Since yesterday, China’s trending topic lists are all about recycled sanitary pads, unhygienic disposable underwear, and water-injected shrimp.

Why, you might wonder?

It has everything to do with the 35th edition of China’s consumer day show, ‘CCTV 3.15 Gala’ (3·15晚会). It aired on Saturday night, becoming one of the most-discussed topics on Chinese social media for exposing malpractices across various companies and industries.

The famous consumer rights show, which coincides with World Consumer Rights Day, is a joint collaboration between CCTV and government agencies. It has been broadcast live on March 15 since 1991.

Each year, the theme of the show varies slightly, but its core mission remains unchanged: to educate people on consumer rights and expose violations while holding companies accountable.

At the time of writing, topics exposed on the show are dominating trending & hot lists across multiple platforms, from Weibo to Douyin, and from Kuaishou to Toutiao.

Weibo’s hot trending list dominated by 315-related topics.

I’ll give you a quick walkthrough of three major stories that have sparked the most discussion online.

1️⃣🚨 “Recycled” Counterfeit Diapers & Sanitary Napkins

The first big story involves a company from Liangshan in Jining called Liangshan Xixi Paper Products (希希纸制品有限公司), which was exposed for selling so-called “refurbished” (翻新) sanitary pad and baby diapers.

The company’s owner, Mr. Liu (刘), bought up scraps and defective sanitary napkins and baby diapers from recognized brands for anything from 260 RMB ($36) to 1400 RMB ($193) per ton. He then repackaged and resold them to unsuspecting consumers, both online and offline, making significant profits.

The incident has a lot of impact. Some of the brands involved are big and reputable Chinese companies, including Freemore (自由点) and Sofy (苏菲), some of China’s most popular feminine hygiene brands.

On Saturday night, after the scandal was brought to light, virtually all of the brands involved halted their e-commerce livestreams. Behind the scenes, marketing crises teams gathered to create statements, which soon were published online.

Sofy responded by stating that the disposal of their non-conforming products is 100% handled within a closed-loop system, ensuring they cannot be resold or reused. They also denied manufacturing the products with their branding shown in the 315 Gala and pledged to fully cooperate with authorities to combat counterfeit and substandard goods (hashtag #苏菲发声明#, over 130 million views).

In response to this incident, the authorities in Jining have undertaken various actions. They have detained those responsible and launched a citywide campaign to oversee the production and sale of sanitary napkins and baby diapers.

In online comment sections, many Chinese netizens argue that the entire industry should be investigated to prevent similar violations from recurring, as this is not the first time such issues have come to light. How did products with defects end up for sale? How can people be sure that their diapers and sanitary pads aren’t counterfeit?

In 2024, there have been multiple online discussions about the safety of Chinese sanitary pads after an online film maker exposed how illegal factories are recycling used materials, including shredded pads and diapers, into new sanitary products. These contaminated pads, sold cheaply on e-commerce platforms, have been linked to pelvic inflammation and other gynecological problems.

2️⃣🚨 Disposable Underwear Sewn by Hand, Stored Next to Trash

The second major story revealed by the 315 Gala involves disposable underwear produced by local manufacturers in the city of Shangqiu. It was uncovered by investigative reporters that many of these manufacturers do not sterilize their disposable underwear products at all. They store them in unsanitary conditions, and use toxic chemicals. Additionally, they falsely advertise their products as 100% cotton when, in reality, they are made of polyester.

Disposable underwear has become more popular in China in recent years. This is not necessarily disposable incontinence underwear, or the kind you only see in hospitals, but it’s one-time wear underwear that is sold at Miniso or Watsons and promoted as a hygienic and convenient solution for workers or travelers, for use in hotels, spas, and beyond.

Among the various companies found to be violating production standards, one company (Mengyang Clothing 梦阳服饰) had a particularly chaotic production workshop. A reporter, going undercover as a potential buyer, entered the factory and saw how workers were sewing disposable underwear with bare hands, without any sterilization, and storing them right next to piles of garbage.

Among the brands involved are those regularly sold on platforms like Taobao, including Beiziyan (贝姿妍), Chuyisheng (初医生), and Langsha (浪莎). They’ve now been removed, and Shangqiu authorities have already established a joint task force to further tackle and investigate the situation.

A related hashtag (#一次性内裤爆雷#) has received over 310 million views by now on Weibo, showing just how concerned people are about the topic. Last year, one Douyin influencer (@黑犬酱·MO) also exposed a factory for the messy and chaotic circumstances under which they produce disposable underwear, after she ended up with a gynecological infection after wearing disposable underwear. Other people shared similar experiences.

3️⃣🚨 Shrimp, with an Extra Serving of Phosphates

The third big story exposed fraudulent practices in the seafood industry, where frozen shrimp suppliers were found illegally adding excessive amounts of phosphates as a water-retention agent.

Phosphates are widely used as food additives in seafood to preserve freshness and texture, but in this case, the process was exploited to artificially increase the weight of shrimp for profit.

One reporter uncovered a facility where shrimp were soaked in phosphates for over 10 hours, resulting in a phosphate content of 30%—far exceeding legal limits.

At another seafood facility, shrimp were rapidly frozen after chemical soaking, followed by an additional coating process to further increase weight. In some cases, only 30% of the final weight was actual shrimp after defrosting.

Beyond the deceptive nature of these practices, the overuse of phosphates poses serious health risks, including digestive issues, or increased risk of cardiovascular diseases.

One worker at the seafood plant interviewed by one of the reporters admitted that they never eat the shrimp they process, saying: “Here on the coast, we only eat fresh shrimp.”

🔁🇨🇳 Business as Usual

These stories, along with other brands and fraudulent practices exposed by CCTV, have sparked anger among netizens. Many women voiced concerns about the safety of sanitary pads. Others wondered about the quality of their seafood. Some vowed never to buy disposable underwear again. Parents angrily asked why they had to question the safety of the diapers for their babies.

An old Dutch saying goes, “Trust arrives on foot and leaves on horseback.” It can take years to build a reputation, but a single bad incident can ruin people’s trust in an instant. This is especially true in China, where public trust in well-known brands has been repeatedly shaken by scandals. A single product crisis can not only severely damage a company’s reputation, but even lead to an erosion of trust in the entire industry.

➡️ The most infamous and devastating example, which left a deep scar on consumer trust, was the 2008 melamine scandal, in which dairy manufacturers deliberately added melamine, an industrial chemical—to diluted raw milk to falsely boost its protein content. Among the infants and children who consumed the tainted milk, over 250,000 cases of health problems were reported. 52,000 children were hospitalized, and six infants lost their lives.

Although the milk powder scandal became a turning point for food and product safety regulations in China, leading to stricter oversight and improved industry standards, it also fueled deep consumer distrust. Even as Chinese brands worked to enhance quality and adopt international safety standards, many consumers remained hesitant to trust them.

➡️ Last year’s cooking oil scandal, involving transport trucks and cargo ships being used to carry both cooking oil and toxic chemicals without proper cleaning procedures, again fueled many discussions about public safety and if people can trust the products they use on a daily basis. It raised public concern not just about unsafe food-handling practices, but also about a myriad of other problems, including a lack of enforcement, bureaucratic inefficiency, power plays, public deception, and especially a lack of transparent communication in the aftermath of such scandals.

🔹 Somewhat ironically, CCTV’s 315 Gala is tackling precisely this issue. By exposing unsafe products and illegal business practices, the show puts brand names, details, and investigations into the public eye. In doing so, they help shape an online discourse where state media, local authorities, and consumers unite in their fight against industry misconduct.

At the end of the day, both brands and consumers have become familiar with the playbook that follows such crises when they are exposed on the 315 Gala.

🔍 Today, an interesting blog by Market News (市场资讯) published on Sina Finance (“开了24年的315晚会 四大规律你懂么”), voiced a critique of the Consumer Day show, arguing that the show, instead of an actual solution for China’s food & product safety, has become more like an annual ritualistic spectacle for the people, a cathartic pressure valve for public frustration.

The author observes four patterns in relation to scandals exposed on the show.

📌 Businesses & consumers follow the same old script

The apologies are ready, the bows are rehearsed, and the damage control strategies are in place.

After so many years of getting exposed, Chinese companies no longer panic after being featured on the show. They have their response templates prepared and a crisis strategy to manage public outrage. Meanwhile, e-commerce platforms swiftly cut ties with implicated brands and showcase new quality control measures, while consumers are comforted with apology letters and discount coupons before getting distracted by the next headlines.

📌 Authorities/regulators also stick to their routine playbook

Similarly, Chinese regulators have a scripted response ready to demonstrate their proactiveness in handling the situation. They quickly issue official statements, ensuring to include phrases like “immediate shutdown,” “ongoing investigation,” and “fines will be imposed.”

📌 The dark side of the industry will still be there

Big businesses prioritize profit over ethics, and as long as the profits outweigh the fines, companies will continue to test regulatory boundaries. There will always be loopholes to exploit, ensuring that these scandals will happen again.

📌 Only small companies face real consequences

While major corporations have the capital and resources to weather a public relations crisis, it is only the small companies without strong investor backing that fail to recover after being exposed on the 315 Gala. This also means that these scandals often don’t actually lead to industry reform.

Scrolling through Chinese social media today, it’s evident that the combined force of social media and the CCTV 315 Gala show has an immense impact.

But public outrage has a short lifespan.

The more consumers grow accustomed to scandals, the more consumer tolerance increases, and the more corporate ethics degrade.

Public distrust remains. The anger is there. But the scandals continue.

The CCTV 315 Gala provides an opportunity for everyone to be angry about it for a day.🔚

There were even more consumer scandals this week, which you can read about below. Special thanks to Miranda Barnes for her input and contributions to this week’s newsletter—be sure to check out her podcast recommendation as well.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

What’s Trending

What’s Behind the Headlines

Last week and into the beginning of this week, the Two Sessions—China’s annual parliamentary meetings—were trending on Weibo and other Chinese social media platforms. Chinese online media were filled with coverage, yet Western newspapers had surprisingly little to say about these meetings.

I listened to a well-known podcast by two British political commentators: The Rest Is Politics, hosted by Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart. They talked about how little the Western world has been reporting about the Two Sessions in China.

This is how the podcast was started by Campbell:

“(..) Because most of our media hasn’t bothered with it, we should talk about the China National Congress they just had (..) The reason I wanted to talk about China is that we are in this world where we all tell each other that there are two superpowers in the world: the United States and China. And the United States, we cover and discuss every single aspect of everything that’s been happening inside Donald Trump’s White House—(..), we’re even talking about the woman who walks alongside Trump carrying his bags and knocking the dandruff off his suit and all that sorts of stuff. And yet China has just held its Two Sessions, which is the National Congress and the big advisory body, and it’s as if it never happened.

Over the past few days, I’ve been asking people if they’re aware of anything big happening in China recently, and nobody knows.

Now, I won’t put you on the spot, Rory, because it would be too cruel, but if I asked people to name the seven members of the Chinese Communist Party Politburo Standing Committee—probably the seven most powerful people in China—most of our listeners won’t know.

So, is this a language thing? Is it because Trump floods the zone with so much shit that we just find ourselves poking in the turds, deciding which piece to focus on before he drops the next one?

Or is it that we maybe haven’t fully caught up with just how important China is now in terms of our lives, as much as their own?”

In this podcast, the two hosts acknowledged that Trump, and, of course, the ongoing war, dominate media coverage in the West. But they made a very valid point in questioning how people could be ignoring such a major political event in China, emphasizing just how crucial China is on the world stage.

They argued that mainstream media editors simply don’t prioritize China—not because there aren’t great journalists covering it, but because it’s not seen as a pressing topic. They also suggested that this lack of coverage isn’t always due to disinterest (there’s no doubt the world is interested in China), but that language and cultural barriers might also play a role.

Yet, as pointed out in the podcast, here we are: the West, living under Trump’s influence, reacting from tweet to tweet, tantrum to tantrum, while practically disregarding Xi’s long-term vision—his roadmap for China from 2021 to 2035 and then from 2035 to 2050—which follows a methodical strategy that will inevitably shape the future.

You can watch or listen to the podcast here.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

Dear Reader

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

A look back at the three major phases of China’s social media — and why What’s on Weibo is evolving into Eye on Digital China.

Published

3 months agoon

November 12, 2025

This edition of the Eye on Digital China newsletter by Manya Koetse was sent to premium subscribers. Subscribe now to receive future issues in your inbox.

“Do you still remember going to the internet cafe, paying 2 yuan ($0.30) per hour during the day or 7 yuan ($1) for an all-nighter? Staying up playing games and surfing around?”

It’s the kind of content you’ll often see today on platforms like Douyin or Bilibili — nostalgic videos showing smoky internet cafes (wangba 网吧) from the early 2000s, where people chatted on QQ or played World of Warcraft on old Windows PCs while eating instant noodles. These clips trigger waves of nostalgia, even among internet users too young to remember that era themselves.

Internetcafe in 2005, image via 021zhaopin.com

The current nostalgia wave you see on Chinese social media is indicative of how China’s digital world has evolved over the past 25 years, shifting from one era to the next.

As I welcome a new name for this newsletter and say goodbye to ‘Weibo Watch’— and, in the longer run, to the ‘What’s on Weibo’ title, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic myself. It seems like a good moment to look back at the three major stages of Chinese social media, and at the reason I started What’s on Weibo in the first place.

1. The Blogging Boom (2002–2009): The Early Rise of Chinese Social Media

When I first came to China and became particularly interested in its online environment, it was the final phase of the early era of Chinese social media — a period that followed soon after the country had laid the foundations for its internet revolution. By 1999, the first generation of Chinese internet giants — Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Sina — had already been founded.

China’s blogging era began with the 2002 launch of the platform BlogChina.com (博客中国), followed by a wave of new platforms and online communities, among them Baidu Tieba and Renren. By around 2005, there were roughly 111 million internet users and 16 million bloggers, and the social impact was undeniable. 2005 was even dubbed China’s “year of blogging.” 1

Chinese writer Han Han (韩寒, born 1982), a high-school-dropout-turned–rally car racer, became one of the most-read figures on the Chinese internet with his sharp and witty blogs. He was just one among many who rose to fame during the blog era, becoming the voice of China’s post-1980s youth.

The rebel of China’s blog era, Han Han, became of voice of his generation.

When I moved to Beijing in 2008, I had a friend who was always out of money and practically lived in an internet cafe in the city’s Wudaokou district, not far from where I studied. We would visit him there as if it were his living room — the wangba was a local hangout for many of us.

Not only online forums and blogging sites were flourishing at the time, but there was also instant messaging through QQ (腾讯QQ), online news reading, and gaming. Platforms like the YouTube equivalents Tudou (土豆) and Youku (优酷) were launched, and soon Chinese companies began developing more successful products inspired by American digital platforms, such as Fanfou (饭否), Zuosa (做啥), Jiwai (叽歪), and Taotao (滔滔), creating an online space that was increasingly, and uniquely, Chinese.

That trajectory only accelerated after 2009, when popular Western internet services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, became inaccessible from within mainland China.

⚡ The launch of Sina Weibo in 2009 came at a crossroads for China’s social media landscape: it was not only a time when many foreign platforms exited China, but also when internet cafes faced major crackdowns.

As a foreigner, I don’t think I ever visited internet bars in Beijing anymore by that point — internet use had largely shifted to home connections. Laptop ownership was rising, and we all had (pre-smartphone) mobile phones, which we used to text each other constantly, since texting was cheaper than calling.

Some of the mobile phones in China’s 2009 top 10 lists.

Weibo came at just the right time. It filled the vacuum left by the online crackdowns across China’s internet while still benefiting from the popularity of blogging. Weibo (微博), after all, literally means “micro-blog” — micro because the number of characters was limited, just like Twitter, making short-form posts the main way of communication.

Weibo quickly became hugely successful, for many more reasons than just timing. Its impact on society was so palpable that its trending discussions often seeped into everyday conversations I had with friends in China.

In English-language media, I kept reading about what was being censored on the Chinese internet, but that wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to know — I also wanted to know what was on Weibo, so I could keep up with my social circles.

That question planted the seed for What’s on Weibo: the simple curiosity of “What are people talking about?” What TV series are popular? What jokes and controversies are everyone discussing (but that I never fully grasped)? I wanted to get a sense of an online world that was, in many ways, intangible to outsiders — including myself. As I had moved back to Europe by then, it was also a way for me to stay connected to those everyday conversations unfolding online in China.

With scissors, glue, and some paper, I started sketching out what a future website might look like.

Papercrafting the idea for a website named ‘What’s on Weibo’ in 2012.

And in March 2013, after doing my best to piece it together, I launched What’s on Weibo and began writing — about all kinds of trends, like the milk powder crisis, about China’s many unmarried “leftover men” (shengnan 剩男), and about the word of the moment, “Green Tea Bitch” (lǜchá biǎo 绿茶婊) — a term used to stereotype ambitious women who act sweet and innocent while being seen as calculating or cunning.

2. From Weibo to the Taobao Moment: China’s Mobile Social Era: (2010–2019)

Around 2014–2015, people started saying Weibo was dead. In fact, it hadn’t died at all — some of its most vibrant years were still ahead. It had simply stumbled into the mobile era, along with China’s entire social media landscape.

As mobile internet became more widespread and everyone started using WeChat (launched in 2011), new mobile-first platforms began to emerge.2 In 2012–2013, for example, apps like Toutiao and Xiaohongshu (小红书, RED) were launched as mobile community platforms. With the rapid rise of China’s new tech giants — Bytedance, Meituan, and Didi — a new mobile era was blossoming, leaving the PC-based social media world far behind.

Spending another summer in Beijing in 2014, I called it the “Taobao Moment” — Taobao being China’s most successful online marketplace, a platform for buying and selling practically everything from clothes and furniture to insurance and even Bitcoins. At the time, I thought Taobao captured everything Beijing was at that moment: a world of opportunities, quick decisions, and endless ways to earn and spend money.

On weekends, some of my friends would head to the markets near the Beijing Zoo to buy the latest dresses, purses, jeans, or shoes. They’d buy stock on Saturday, do a photo shoot on Sunday, and sell the goods online by Monday. You could often spot young people on the streets of Beijing staging their own fashion shoots for Taobao — friends posing as models, Canon cameras in hand.

During that period, What’s on Weibo gradually found its audience, as more people became curious about what was happening on Chinese social media.

Around 2016, Weibo entered another prime era as the “celebrity economy” took off and a wave of “super influencers” (超级红人) emerged on the platform. Papi Jiang stood out among them — her humorous videos on everyday social issues made her one of China’s most recognizable online personalities, helping to drive Weibo’s renewed popularity.

Witty Papi Jiang was a breath of fresh air on Weibo in 2016.

People were hooked on social media. Between 2015 and 2018, China entered the age of algorithm- & interest-driven multimedia platforms. The popularity of Kuaishou’s livestreaming and Bytedance’s Douyin signaled the start of an entirely new era.

3. The New Social Era of AI-fication and Diversification (2020–Current)

China’s social media shifts over the past 25 years go hand in hand with broader technological, social, and geopolitical changes. Although this holds true elsewhere too, it’s especially the case in China, where central leadership is deeply involved in how social media should be managed and which direction the country’s digital development should take.

Since the late 2010s, China’s focus on AI has permeated every layer of society. AI-driven recommendation systems have fundamentally changed how Chinese users consume information. Far more than Weibo, platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu have become popular for using machine-learning algorithms to tailor feeds based on user behavior.

China’s social media boom has put pressure on traditional media outlets, which are now increasingly weaving themselves into social media infrastructure to broaden their impact. This has blurred the line between social media and state media, creating a complex online media ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s not just AI and media convergence that are reshaping China’s online landscape — social relationships now dominate both information flows and influence flows. 3 Not everyone is reading the same headlines anymore; people spend more time within their own interest-based niches. It’s no longer about microblogging but about micro-communities.

China now has 1.12 billion internet users. Among new users, young people (aged 10–19) and the elderly (60+) account for 49% and nearly 21%, respectively. The country’s digital environment has never been more lively, and social media has never been more booming.

As a bit of a dinosaur in China’s social media world, Weibo still stands tall — and its trending topics still matter. But the community that was once at the heart of the Chinese internet has dispersed across other apps, where people now engage in more diverse ways than ever.

In China, I notice this shift: where I once saw the rise of Weibo, the Taobao boom, or the Douyin craze, I now see online and offline media increasingly converging. Social media shapes real-life experiences and vice versa, and AI has become integrated into nearly every part of the media ecosystem — changing how content is made, distributed, consumed, and controlled.

In this changing landscape, the mission of What’s on Weibo — to explain China’s digital culture, media, and social trends, and to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online spaces — has stayed the same. But the name no longer fits that mission.

Over the past few years, my work has naturally evolved from Weibo-focused coverage to exploring China’s digital culture through a broader lens. The analysis and trend updates will continue, but under a new name that better reflects a time when Weibo is no longer at the center of China’s social media world: Eye on Digital China.

For you as a subscriber (subscribe here), this means you can expect more newsletter-based coverage: shorter China Trend Watch editions to keep you up to date with the latest trends, along with other thematic features and ‘Chapter’ deep dives that explore the depth behind fleeting moments.

For now, the main website will remain What’s on Weibo, but it will gradually transition into Eye on Digital China. I’ll keep the full archive alive — more than twelve years of coverage that helps trace the digital patterns we’re still seeing today. After all, the story of China’s past online moments often tells us more about the future than the trends of the day.

Thank you for following along on this new journey.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 Liu, Fengshu. 2011. Urban Youth in China: Modernity, the Internet and the Self. New York: Routledge, 50.

2 Mao Lin (Michael). 2020. “中国互联网25年变迁:两次跃迁,四次浪潮,一次赌未来” [25 Years of China’s Internet: Two Leaps, Four Waves, and a Gamble on the Future]. 人人都是产品经理 (Everyone Is a Product Manager), January 3. https://www.woshipm.com/it/3282708.html.

3 Yang, Shaoli (杨绍丽). 2025. “研判2025!中国社交媒体行业发展历程、重点企业分析及未来前景展望:随着移动互联网兴起,社交媒体开始向移动端转移 [Outlook for 2025! The Development History, Key Enterprises, and Future Prospects of China’s Social Media Industry: With the Rise of Mobile Internet, Social Media Has Shifted to Mobile Platforms].” Zhiyan Consulting (智研咨询), February 7. https://www.chyxx.com/industry/1211618.html.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in the comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient — we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo.

Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. Both feature the same new content — so you can subscribe or read wherever you prefer. If you’re already subscribed on one platform and would like to move your subscription over, just let me know and I’ll help you get set up.

© 2025 Manya Koetse. All rights reserved.

China Media

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Published

10 months agoon

March 30, 2025

“This man is doing God’s work. In just six hours, he eliminated all Western media propaganda about China,” Chinese influencer Li Sanjin (李三金) said in one of his videos this week. The man he referred to, allegedly doing ‘God’s work,’ is the American YouTuber and online streamer Darren Watkins, better known as IShowSpeed or Speed, who visited China this week and livestreamed from various locations.

With 37 million followers on his YouTube account, Watkins’ visit hasn’t exactly flown under the radar. His streams from China have already accumulated over 17.5 million views on YouTube alone, and he also became the talk of the week on Chinese social media.

In China, the 20-year-old IShowSpeed is known as Jiǎkànggē (甲亢哥), or “Hyper Bro,” since the immensely popular YouTube star is known for being highly energetic.

Although IShowSpeed is originally known for soccer and gaming-related content, he’s been streaming live from various countries over the past year, from Ecuador to Bolivia, from Australia to Indonesia, from Romania to Japan, and also from the Netherlands, where a mob of fans harassed the YouTuber to such an extent that the influencer fled and panicked, until the police intervened and asked him to shut down the livestream for safety reasons — which he did not comply with.

It was not the only time IShowSpeed’s visit got chaotic. He also got into trouble during livestreams from other countries. While streaming from Norway, he injured his ankle and was swarmed by a crowd while trying to get out. In Greece and Indonesia, he had to ask for police support as well. In Thailand, he crashed a tuk-tuk into a temple wall.

In China, IShowSpeed’s livestreams went far more smoothly, and netizens, state media, and other official channels raved about his visit and its favorable portrayal of the country and its culture.

🔹 Symbol of Cultural Exchange & Positive Diplomacy

“Jiǎkànggē” became one of the viral terms of the week, on Weibo, Kuaishou, Douyin, and Toutiao. During his China trip, the livestreamer hit several YouTube milestones — not only breaking the 37 million subscriber mark while on stream, but also surpassing the magic number of 10 million views in total.

Watkins, also known for being (sometimes aggressively) loud and chaotic, suddenly emerged as a symbol of cultural exchange and positive diplomacy. The past week saw hashtags such as:

#️⃣”IShowSpeed gives young foreigners a full-window view into China” (#甲亢哥给国外年轻人开了全景天窗#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed’s Shanghai livestream breaks Western filter on China” (#甲亢哥上海直播打破西方对中国滤镜#)

#️⃣”American influencer IShowSpeed amazed by stable wifi on China’s high-speed train” (#美国网红甲亢哥被高铁稳定网络震惊#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed praised deep tried tripe for being incredibly delicious” (#甲亢哥赞爆肚太好吃了#), or

#️⃣ “IShowSpeed bridges the cultural divide” (#甲亢哥弥合文化鸿沟#).

While in Chinese media, Watkins was lauded for shining a positive light on China, this message was also promoted on English-language social media, where he was praised by the Chinese embassy in the US (#驻美大使馆称赞甲亢哥中国行#), writing:

Post by Chinese Embassy in the US on X, March 26.

“This 20-year-old American internet star is bridging cultural gaps through digital means and creating new channels for foreign audiences to better understand China.”

So what exactly did IShowSpeed do while in China?

On March 24, Watkins livestreamed from Shanghai. He wandered around the city center, visited a KFC, danced with fellow streamers, stopped by a marriage market, ate noodles, played ping-pong, had hotpot, joined a dragon dance group and got acquainted with some traditional Chinese opera performance, and walked along the Bund.

On March 26, he streamed from Beijing, starting in Donghuamen before briefly entering the Forbidden City—dressed in a Dongbei-style floral suit. He later took a stroll around Nanluoguxiang and the scenic Houhai lake, rode a train, and finally visited the Great Wall, where he did backflips.

In his stream on March 28, Watkins traveled to Henan to visit the famous Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng, hoping to find a master to teach him kung fu. He trained with Shaolin monks—footage that quickly went viral.

Lastly, on March 29, he opened his own Weibo account and published his first post. On Douyin, he shared a video of his visit to Fuxi Mountain in Zhengzhou, featuring the popular “Stairway to Heaven” tourist spot.

On social media, many viewers were captivated by the content. One major talking point was the remarkably strong internet connection that allowed him to livestream for six-hour stretches without losing signal in Shanghai. (Though his Beijing stream started off patchier, the drop was minor.) For many, it symbolized the quality of China’s 5G services.

Foreign viewers also praised how safe, friendly, and clean the country appeared, and how his streams highlighted various aspects of Chinese culture—from everyday people to traditional arts and local cuisine.

🔹 Telling & Spreading China’s Stories Well

It is no wonder the success of the Jiǎkànggē livestreams is celebrated by Chinese official media in an age where China’s foreign communication aims to increase China’s international discourse power, shaping how the world views China and making that image more credible, more respectable, and more lovable.

That’s not just an observation — it’s an official strategy. Introduced by Xi Jinping in 2013, “Telling China’s Story Well” (“讲好中国故事”) is a political slogan that has become a key propaganda strategy for China and continues to be a priority in finding different ways of promoting Chinese culture — new ways of telling China’s story in the social media age – while countering Western dominant narratives about China.

In increasingly digitalized times, it is not just about telling China’s story well, but also spreading China’s message effectively — preferably through genuine and engaging stories (Cai 2013; Qiushi 2021).

Especially young, non-official ‘storytellers’ can make China’s image more relatable and dynamic. One major example, highlighted in a 2022 case study by Zeng Dan (曾丹), is Chinese influencer Li Ziqi (李子柒). You’ve probably heard of her, or seen snippets of her videos: she creates soothing, cinematic content depicting China’s countryside lifestyle, focused on cooking, crafts, and gardening. With 26 million followers on YouTube, Li Ziqi became a viral sensation who successfully communicated an authentic and appealing ‘China story’ to a broad global audience.

Li Ziqi in one of her YouTube videos.

Although the calm and composed Li Ziqi and the loud, chaotic IShowSpeed couldn’t be more different, they have some things in common: both have large international fanbases, including their millions of YouTube subscribers; they offer perspectives that differ from Chinese state media or official channels; and they have the capacity not just to tell China’s story well, but to spread it effectively through videos and livestreams.

🔹 Spontaneous Stream or Scripted Propaganda?

IShowSpeed’s China streams have triggered a wave of responses from fans and viewers, sparking discussions across international social media and even making newspaper headlines.

In English-language online media spheres, there appear to be a range of perspectives on Watkins’ China trip:

📌 One prominent view—also echoed by various foreign influencers on YouTube and other platforms—is that IShowSpeed’s visit counters “Western media lies” about China and has successfully shown the “real China” through his livestreams. The Shanghai-based media outlet Radii claimed that “IShowSpeed’s China Tour is doing more for Chinese Soft Power than most diplomats ever could.”

📌 Others challenge this narrative, questioning which dominant Western portrayals of China IShowSpeed has actually disproven. Some argue that the idea of China being a “bleak place with nothing to do where people live in misery” is itself a false narrative, and that presenting IShowSpeed’s livestreams as a counter to that is its own form of propaganda (see: Chopsticks and Trains).

📌 There are also those who see Watkins’ trip as a form of scripted propaganda. To what extent were his livestreams planned or orchestrated? That question has become one of the central points of debate surrounding the hype around his visit.

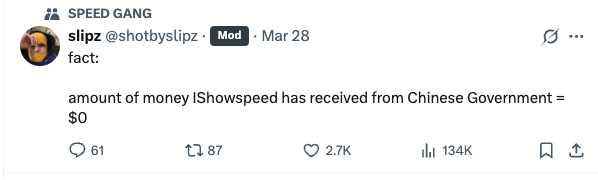

These rumors have been addressed by cameraman Slipz (@shotbyslipz), who took to X on March 28, 2025. Slipz posted that the team is “(..) not making political content, not any documentary and no journalism,” and later added: “Fact: amount of money IShowSpeed has received from Chinese Government = $0.”

But does the fact that IShowSpeed did not receive money from the Chinese government mean that it wasn’t also a form of China promotion?

➡️ Organized — it definitely was. Any media trip in China has to be. IShowSpeed would have needed a visa, he had translators with him, and throughout the streams it’s evident that local guards and public security officers were present, walking alongside and helping to keep things under control, especially in crowded areas and at major tourist spots — from Nanjing Road in Shanghai to an entire group of guards seemingly accompanying the entourage in the Forbidden City.

One logistical “advantage” to his visit was the fact that YouTube is blocked in China. While some Chinese fans do bypass the Great Firewall to access the platform, IShowSpeed remains far less known in China than in many other countries — a factor that likely contributed to how smoothly the streams went and helped prevent chaos. The team also launched a Douyin account during the trip, where he now has over two million followers. (To stream directly to their 37 million followers on YouTube, Watkins’ team either needed a VPN to access WiFi or had arranged roaming SIM cards to stay connected.)

➡️ Was it staged? Many parts clearly weren’t: casual public conversations, spontaneous barber visits in both Shanghai and Beijing (with barbers looking unsure of how to handle the situation), and wholesome fan encounters. There was even a moment when Watkins walked into a public restroom and forgot to mute the sound.

But other parts of the trip were undeniably staged — or at least framed to appear spontaneous. When visiting a marriage market in Shanghai, for instance, two actors appeared, including one woman with a sign stating she was looking for someone “capable of doing backflips.”

When Watkins took a “random” ride in what was described as the fastest car in China — the Xiaomi SU7 Ultra — the vehicle appeared to be conveniently parked and ready.

Similarly, when the streamer “ran into” Chinese-American TikTok influencer Miles Moretti (李美越) in Beijing, it turned out to be the person who would give him the now-iconic bright Dongbei flower suit and accompany him on his journey.

The ping-pong, the kung fu, the Peking opera, the hotpot, the Forbidden City tour — it all plays into the kinds of experiences that official channels also like to highlight. While likely planned by Watkins’ team in coordination with local partners, it was all far more orderly and tourism-focused than, for example, Watkins’ chaotic visit to the Netherlands.

Watkins and his entourage were also well-informed about the local dos and don’ts. At one point, Watkins even mentions “following the rules,” and when Moretti tells him mid-stream that “somebody very important lives on our left,” Watkins asks “Who?” — but the camera zooms out and the question goes unanswered, suggesting they may have been reminded that certain names or topics were off-limits (judge the moment for yourself here).

The livestream didn’t always go exactly the way Watkins wanted, either. When he attempted to take more random walks around the city, the crew appeared to be informed that some areas were off-limits, and he was asked to return to the car to continue the trip (clips here and here).

🔹 The “Nàge” Song

One major talking point surrounding IShowSpeed’s China livestreams was “the N-word.” No, not that N-word — but the Chinese filler word “nàge” or “nèige” (那个). Like “uhm” in English or “eto” in Japanese, “nàge” is a hesitation marker commonly used in everyday Mandarin conversation. It also functions as a demonstrative pronoun meaning “that.”

The word has previously stirred controversy because of its phonetic resemblance to a racial slur in English. In 2020, an American professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business was even temporarily suspended after using the word during an online communications class — some students misunderstood its context and took offense.

The word — and the song “Sunshine, Rainbow, White Pony” (阳光彩虹小白马) by Chinese singer Wowkie Zhang (大张伟), which repeatedly features the word nàge in its chorus — popped up multiple times during Watkins’ trip. The catchy tune essentially became the theme song of his visit.

The first nàge moment actually already appeared within the first five minutes of Watkins’ Shanghai stream, when a Chinese comedian approached him on the street, trying to recall a joke. “What?!” Watkins reacted, with laughter in the background. “That’s not a joke, you said n**! It’s my first five minutes in China!” he exclaimed, before patting the man’s back in a friendly gesture, clearly not offended.

🔄 It resurfaced again within the first hour when Watkins visited a marriage market and one of the performers sang the Wowkie Zhang song. Watkins initially acted shocked, then demanded they sing it again — only to burst out laughing and start singing along.

🔄 Later, he sang the song again with a street saxophonist and encouraged others to join in.

🔄 At other moments, he played up the drama again, feigning anger when a crowd broke into the chorus, and it became a recurring gag throughout the streams.

These incidents all seem staged. One of the main reasons Watkins is known to many netizens in China is because of an older video clip showing his exaggerated reaction to the nàge song — dating back to at least 2022. So while it may have looked spontaneous, Watkins was already familiar with the word and the viral song long before his China trip.The attention given to the nàge ‘controversy’ was likely amplified for views and engagement.

While Watkins was clearly in on this part of the show — as with others — he also seemed genuinely, and at times amusingly, unaware of many things in China. He repeatedly referred to RMB as “dollars,” mistook elderly women for retired YouTube streamers, and even assumed that a woman livestreaming near the Forbidden City was reading his chat and trying to collaborate with him — although she seemed totally uninterested and was just minding her own business.

🔹 A Win-Win Situation

In the end, IShowSpeed’s visit highlighted two sides effectively doing their job. Watkins and his team successfully arranged a YouTube trip that generated high ad revenue, attracted millions of new subscribers, and boosted his brand and global fame.

On the Chinese side, there was clearly coordination behind the scenes to ensure the trip went smoothly: avoiding controversy, ensuring safety, and showcasing positive aspects of Chinese culture. From traditional opera and kung fu to ping pong, IShowSpeed’s content gave center stage to the kinds of cultural highlights that align closely with China’s official narratives and tourism goals. Even if the government didn’t pay the YouTuber directly, as his team has emphasized (and there’s no reason to doubt them), the trip still fit seamlessly into China’s soft power strategy.

IShowSpeed’s China visit has created a unique media moment that resonates for several reasons: it’s the encounter of a young modern American with old traditional China; it is a streamer known for chaos visiting a nation known for control. And it brings different benefits to both sides: clicks and ad revenue for IShowSpeed, and free foreign-facing publicity for China.

No, IShowSpeed didn’t undo years of critical Western media coverage on China. But what his visit shows is that we’ve entered a phase where China is becoming more skilled at letting others help tell its story — in ways that resonate with a global, young, online audience. He didn’t do “God’s work.” He simply did what he always does: stream. And with China’s help, he streamed China very well.

There’s so much more I want to share with you this week — from Chinese reactions to the devastating Myanmar earthquake, to a recent podcast I joined with Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf (link in Dutch, for those interested). But it also happens to be my birthday today, and I’m really hoping to still grab some birthday hotpot — so I’ll wrap this up here. I’ll keep you informed on the other trends in the next newsletter.📨.

Best,

Manya

(@manyapan)

References:

Cai, Mingzhao 蔡名照. 2013. “Telling China’s Stories Well and Spreading China’s Voice: Thoroughly Studying and Implementing the Spirit of Comrade Xi Jinping’s Important Speech at the National Conference on Propaganda and Ideological Work [讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音——深入学习贯彻习近平同志在全国宣传思想工作会议上的重要讲话精神].” People’s Daily 人民日报, October 10. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1010/c1001-23144775.html. Accessed March 29.

Qiushi 求是网. 2021. “Xi Jinping: Telling China’s Story Well, Spread China’s Voice Well [习近平:讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音].” Qs Theory, June 6. http://www.qstheory.cn/zhuanqu/2021-06/02/c_1127522386.htm. Accessed March 29.

Zeng Dan 曾丹. 2022. “How to Tell China’s Story Well: Taking Li Ziqi as an Example [如何讲好中国故事——以李子柒为例].” Progress in Social Sciences 社会科学进展 4 (1): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.35534/pss.0401002.

What’s Featured

Quite terrifying and interesting, as this trending story touched upon so many different issues.

What started as a single snarky comment on Weibo spiraled into an online witch hunt, exposing not just some dark sides of online Kpop fandom but also, most importantly, the vulnerabilities in China’s digital privacy.

Read the story, the latest by Ruixin Zhang 👀

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment7 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West