Featured

Weibo Watch: The Last ‘T’ Standing

The last ‘T’ standing, Gaokao week, and why Chinese publishers are boycotting JD’s 618 festival.

Published

1 year agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #30

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – The Last T-Word

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s On Screen – Top TV Shows to watch

◼︎ 5. What’s Remarkable – Taiwan students lack knowledge on Chinese history

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Will China save Lululemon?

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Divorce peek after Gaokao

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – “Sunscreen Warriors”

Dear Reader,

This week marked the 35th anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown, a time when censorship and online control in China intensify.

Ten years ago, around the 25th Tiananmen anniversary, I was browsing a bookstore in Beijing when I came across a book titled My Homeland in the 1980s (我的故乡在八十年代), its cover showing students reading and sitting at Tiananmen Square. The book, featuring dozens of interviews, was supposed to discuss the events of the 1980s in China, reassessing the era’s impact on the country today.

I immediately bought the book, as I was curious to see how this work, published in 2013, would narrate the events of the summer of 1989. Perhaps I was naive, but after carefully hopping from chapter to chapter, from page to page, I was stunned to discover that while the Tiananmen Square was referred to several times throughout the book, which thoroughly discussed happenings from 1980-1990, there was no reference to the student protests or June 4th at all. Not one single sentence—it was as if it had never happened.

Of course, the surprise wasn’t that big. I was well aware of the so-called ‘Forbidden Ts,’ highly sensitive and often censored topics which are closely tied to the end of Twitter in China and the rise of Weibo in 2009.

These ‘Three Ts’—which even have their own Wikipedia page—refer to Chinese taboo topics: Tiananmen, Tibet, and Taiwan. You might even call it the ‘Four Ts’ if you include Xinjiang (for T’s sake, borrowing the T from its old reference as East Turkestan).

“The Last ‘T’ Standing”

Many things were happening in the summer of 2009, following a period of a relatively free Chinese internet since 2006 that saw a flourishing of new BBS sites and social media networks, including Facebook and Twitter. The year 2009 was a year of change and key events: the Jasmine revolution was taking place, there was growing unrest in Xinjiang including the Urumqi riots, and it was the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown.

That year, online censorship was particularly strict, and various websites and discussion boards became inaccessible around June 4th. Some sites displayed a message stating they were “closed for maintenance,” leading to the day sarcastically being nicknamed “Chinese Internet Maintenance Day” (中国网站维护日).

For some sites, their temporary ‘maintenance’ became permanent. While American Twitter disappeared from China, the domestic Sina Weibo emerged—a new social media platform designed to keep information flows under control by censoring sensitive topics and hiding posts containing blocked keywords.

The ‘Four Ts’ remained highly sensitive, and often there would be no results at all when searching for a term like ‘Xinjiang.’

Throughout the years, however, in line with China’s rising importance on the world stage and its growing assertiveness under Xi Jinping, wolf warrior diplomacy, new strategies in digital propaganda, and other factors, most of the forbidden Ts have become not so taboo nor forbidden at all anymore.

There have been various extensive online discussions about Tibet or about Xinjiang – and what Western media are getting wrong about these topics. Nowadays, even the words for ‘Taiwan independence’ – once a censored term – are ubiquitous in China’s online environment as part of the intensified Taiwan reunification social media campaign.

The primary change in these topics is how official accounts now control the narrative, framing them in ways that are not politically sensitive but rather vehicles of Chinese pride and nationalism. This shift enables these subjects to be addressed because there is now an official online discourse providing a context for the conversation.

Tiananmen, however, is the last ‘T’ standing.

If anything, censorship surrounding this ‘T’ has seemingly only grown stricter. During the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen student protests in 2019, there was a complete shutdown of searches for this term on Weibo. As in previous years, Weibo quietly removed the candle icon from its collection of “frequently used emoticons” just before June 4, and also started removing other emojis deemed remotely sensitive, such as the leaf, the cake, the ribbon, and the present.

“Internet Maintenance Day”

During the Tiananmen anniversary in 2022, Weibo saw an uptick in posts using the English phrase “It’s my duty,” relating to a video of a young student in 1989 Beijing answering a foreign reporter on why he was off to march at Tiananmen Square (“Why? I think it’s my duty” – see video). Following this, any mention of the “It’s my duty” slogan was meticulously scrubbed from Chinese social media.

The term ‘May 35’, which became a code word for ‘June 4,’ is also censored, like so many other plays on words. No matter if it’s numbers, different characters, English phrases, or emojis – once a creative way to commemorate Tiananmen’s June 4 becomes popular on Weibo or other platforms, it’s swiftly removed.

This year is no different. As described by Alexander Boyd, the breadth of censorship in China during this 35th Tiananmen anniversary was “breathtaking.”

And so it was somewhat noteworthy when New Zealand national Andy Boreham, a Chinese state media (Shanghai Daily) worker, posted a long thread on X [Twitter] this week about the “Tankman” and Tiananmen, in which he attempted ‘to set the record straight’ by claiming that the idea of the “Tiananmen Square Massacre” is “a U.S.-led myth based on a very real set of events over a few weeks in 1989.”

The first part of Boreham’s now-deleted X thread, screenshot via Fergus Ryan @fryan.

The ‘T-word’ is obviously not censored on X, where Boreham tweets for a foreign audience, not a domestic one. But considering Boreham’s position within the Chinese state media apparatus and the guidance that comes with it,[1] his lengthy discussion of Tiananmen was still unusual. Boreham wrote about the protests and did not deny that there were many casualties, while mainly focusing on the alleged “Tiananmen Square massacre,” which he claimed did not occur. (DW News reporter Monir Ghaedi explains more about Boreham’s post here).

A day later, after Boreham’s post was shared over 5000 times, the entire thread was suddenly deleted.

Although he posted another tweet about Americans dying from gun violence on June 4th, Boreham did not address the deletion of his detailed Tiananmen thread.

Instead, he wrote: “It seems the world isn’t ready for the truth, or even just to face the idea that what they believe is only one version.”

Not a single mention of the deleted post—it was as if it had never happened. Perhaps Boreham’s response had a double meaning when he wrote “it seems the world isn’t ready for the truth”, including how China isn’t ready for this T, even if it’s happening on X. Maybe he had his own private “Internet maintenance day” this June 4th.

Best,

Manya

[1]Ryan, Fergus, Matt Knight, and Daria Impiombato. 2023. “Singing from the CCP’s Songsheet: The Role of Foreign Influencers in China’s Propaganda System.” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 35-36. https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2023-11/Singing%20from%20the%20song%20sheet.pdf?VersionId=mdVBVPrFokz_xlEyhQdz0H3ZPmRs76el.

What’s New

1: Students vs. Chatbots | It’s Gaokao time! Over 13.4 million Chinese students are taking the national college entrance exams this week. For the first time, China’s Gaokao essay topic is about the latest AI developments, sparking discussions on social media platforms about whether AI is actually making life easier or not.

2: The Cost of Cheap Books | Interesting discussions are emerging ahead of JD.com’s major 618 shopping festival this year, following a joint statement from Chinese publishers declaring that the price war on books is no longer sustainable. Of course, bookworms always love getting a good deal on books, but when the deals are just too good, it could harm the publishing industry.

3: Uncle Wang Goes Phnom Penh | Various tribute videos are circulating on Chinese social media this week following the announcement that MFA spokesperson Wang Wenbin is starting his new post as China’s new ambassador to Cambodia. Wang served as the 32nd MFA spokesperson from 2020 to 2024. While some perceive his new role as a “downgrade,” it is more likely a reflection of his importance given the strengthening of Sino-Cambodian relations and Cambodia’s role as a key strategic partner to China in the region.

What’s Trending

- THURSDAY 30 MAY

- 270 million views for the hashtag “Gou Zhongwen Suspected of Serious Disciplinary Violations and Illegal Activities” #苟仲文涉嫌严重违纪违法#.

- Gou Zhongwen is a Chinese politician who served as director of the State General Administration of Sports from 2016 to 2022. He is under investigation for suspected severe violations of Party discipline and the law.

- The probe involving the retired Gou, who is currently being held in custody, is part of a wider government crackdown on corruption in sports. Read more on Caixin here.

- FRIDAY 31 MAY

- After a New York jury found Trump guilty on all 34 counts of falsifying business records in his hush-money criminal trial, his historic conviction – making Trump the first former U.S. president to be found guilty of felony crimes – went top trending on Weibo.

- On Chinese social media, the Trump trial is seen as a spectacle to enjoy, a “historical performance” featuring “Comrade Trump” as the leading figure.

- Political commentator Hu Xijin also commented on the issue, stating that the case triggers the curiosity of Chinese people because they mostly wonder about two things:

1. Will Trump actually go to jail?

2. Can he still run for president?

- MONDAY JUNE 3

- The topic “China has stopped giving away pandas for free for over 40 years” went trending on Weibo, garnering over 440 million views.

- This refers to the policy shift in the 1980s when China stopped gifting pandas to friendly nations for free and switched to “lending” them for shorter periods, with all pandas and their offspring remaining Chinese property.

- The policy, widely supported among Chinese commenters, sparked discussions because of Fu Bao, a panda born in 2020 as South Korea’s first naturally-bred panda.

- •As part of China’s “panda diplomacy” program, Fu Bao was returned to China in early April, but South Korean netizens have now set up a petition to ‘bring back’ their beloved panda.

- WEDNESDAY JUNE 5

- Chinese streaming platform iQIYI faced an online storm this week after asking its paying members to pay an additional fee to watch a livestream of an event related to its hit show, “Become a Farmer.”

- Adding to the frustration, the event itself was free for offline participants, leading to the hashtag “iQIYI – offline free, online paid” (爱奇艺 线下免费线上收费), which garnered 200 million views on Weibo.

- The criticism comes at a time when members are already dissatisfied with price hikes and additional charges for higher streaming quality and early access to content.

- To read more on the hit show “Become a Farmer,” check out our article here.

- FRIDAY, SATURDAY 7&8 JUNE

- Over 13.4 million students sat down for their Gaokao, the national college entrance exams, which started this week and dominated trending topics on Chinese social media.

- Platforms like Weibo and Douyin saw a flood of videos featuring relieved students emerging from the exam room. For many, it’s finally time to relax after weeks of intense studying.

- Some provinces and regions, including Henan and Jiangsu, are offering freebies for those who took the exam, such as free entrance to scenic areas.

What’s the Drama

The latest TV drama to create a lot of buzz and discussion this week is The Double (墨雨云间 Mò Yǔ Yún Jiān), a superdramatic romance/costume series starring, among others, Chinese actress Wu Jinyan (吴谨言), and Chinese actors Wang Xingyue (王星越) and Chen Xinhai (陈鑫海). Wu stars as the female lead, Xue Fangfei, the daughter of a county magistrate who leads a happy and privileged life until everything changes and she gets buried alive by her husband. Don’t worry, she’ll assume another identity to go on a quest for revenge.

To know:

▶️ The series is adapted from the Chinese web novel “Marriage of the Di Daughter” (嫡嫁千金) by Qian Shan Cha Ke (千山茶客).

▶️ The Double immediately became top ranking on Youku’s drama list for 2024, becoming the fastest drama this year to hit 10,000 on Youku’s “heat index.” The series is also scoring well outside of China, scoring 8.5/10 on MyDramaList.

▶️ The drama is a true social media hit: its hashtag has received a staggering 1.59 billion views on Weibo.

The Double is available with English subtitles on Viki here.

What’s Noteworthy

Chinese state media have recently taken a new approach in the discourse surrounding cross-straits relations, highlighting how students in Taiwan lack knowledge about Chinese history and are victims of a “de-Chinafication” education policy. This policy is supposedly embedded in the Chinese history education in Taiwan.

On May 30, state broadcaster CCTV News released a street interview video with Taiwanese students after their college entrance exams, asking them about Chinese history. Some students mentioned that Chinese history was only covered in one or two questions, while others responded with “What is Chinese history?” This topic quickly became the number one trending topic on Weibo (#台湾高中生问中国史是什么#).

In online discussions, many netizens argued that Taiwan’s “pro-independence” education curriculum is purposely distorting views on Chinese history, allegedly leading to a lack of identification with being ‘Chinese,’ raising concerns about the long-term impact of such ‘educational policies.’

What’s Popular

American athletic apparel brand Lululemon has recently been trending on Chinese social media for two reasons. First, reports highlighted significant growth in the Chinese market. In the first quarter of 2024, Lululemon’s sales increased by 10%, with a notable 45% surge in revenue from China. Second, the company’s stock price recently dropped due to concerns over its outlook, exacerbated by the departure of a key executive, Sun Choe, and the significant slowdown in revenue growth in the Americas market in the final quarter of 2023.

These developments have led to speculation in China about whether the Chinese market might be the one to ‘rescue’ the American brand, sparking conversations about the willingness of Chinese consumers to purchase the relatively pricey activewear brand.

However, on social media, many believe Lululemon’s success in China might not be everlasting. Searching for ‘Lululemon alternatives’ on China’s online shopping platforms, some argue that a 50-yuan sweater ($7) is just as comfortable as the original, which costs over 1,000 yuan ($138). Chinese sellers claim that the Lululemon alternatives produced by Chinese OEM factories are indistinguishable from the real product at a much better price. This sentiment is echoed by many Chinese consumers, who find the cheaper made-in-China alternatives to Lululemon just as satisfactory. A related hashtag received over 140 million views on Weibo this week.

What’s Memorable

For this pick from the archive, we revisit an article from 2018 about the post-Gaokao divorce trend. For millions of Chinese students and their parents, the national college entrance exams – taking place this week – are incredibly stressful. To support their child’s performance, some unhappy couples decide to postpone their plans to divorce, leading to a spike in divorce rates shortly after the exams end. Read more here.👇

Weibo Word of the Week

“Sun Protection Warriors” | Our Weibo Word of the Week is fángshài zhànshì (防晒战士), translated as “sun protection warriors” or “sunscreen warriors.”

In recent years, China has seen a rise in anti-tan, sun-protection garments. More than just preventing sunburn, these garments aim to prevent any tanning at all, helping Chinese women—and some men—maintain as pale a complexion as possible, as fair skin is deemed aesthetically ideal.

As temperatures are soaring across China, online fashion stores on Taobao and other platforms are offering all kinds of fashion solutions to prevent the skin, mainly the face, from being exposed to the sun.

On the social lifestyle platform Xiaohongshu, women share all kinds of strategies to avoid sun exposure, from enormous sunhats to reverse hoodies. This extreme anti-sun fashion has led some users to label themselves or others as “sun protection warriors.”

Some people think the trend is going too far, saying that fashionable women nowadays are more like “sunscreen terrorists” (防晒恐怖分子, fángshài kǒngbùfènzǐ).

Image shared on Weibo by @TA们叫我董小姐, comparing pretty girls before (left) and nowadays (right), also labeled “sunscreen terrorists.”

To see more examples of extreme anti-tan fashion and read more about this phenomenon, click here 👇

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Featured image: Part of the image is based on photo taken by photographer Liu Xiangcheng, depicting dozens of students sitting down at Tiananmen Square.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform resurfaces in Africa, a new winter hotspot, why Chinese elites ‘run’ to Tokyo, and more.

Published

2 days agoon

November 21, 2025

🌊 Signals — Week 47 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China, Signals highlights slower trends and online currents behind the daily scroll. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Different from the China Trend Watch (check the latest one here if you missed it), this edition, part of the new Signals series, is about the slower side of China’s social media: the recurring themes and underlying shifts that signal broader trends beyond the quick daily headlines. Together with the deeper dives, the three combined aim to give you clear updates and a fuller overview of what’s happening in China’s online conversations & digital spaces.

For the coming two weeks, I’ll be traveling from Beijing to Chongqing and beyond (more on that soon) so please bear with me if my posting frequency dips a little. I’ll be sure to pick it up again soon and will do my best to keep you updated along the way. In the meantime, if you know of a must-try hotpot in Chongqing, please do let me know.

In this newsletter: Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform in Angola, a new winter hotspot, discussions on what happens to your Wechat after you die, why Chinese elites rùn to Tokyo, and more. Let’s dive in.

- 💰 The richest woman in China, according to the latest list by Hurun Research Institute, is the “queen of pharmaceuticals” Zhong Huijuan (钟慧娟) who has accumulated 141 billion yuan (over 19 billion USD). Women account for over 22% of Chinese billionaires (those with more than 5 billion RMB), underscoring China’s globally leading position in producing wealthy female entrepreneurs.

- 🧩 What happens to your WeChat after you die? A user who registered for NetEase Music with a newly reassigned phone number unexpectedly gained access to the late singer Coco Lee’s (李玟) account, as the number had originally belonged to her. The incident has reignited debate over how digital accounts should be handled after death, prompting platforms like NetEase and Tencent to reconsider policies on long-inactive accounts and take stronger measures to protect them.

- 📱 Although millions of viewers swoon over micro-dramas with fantasy storylines where rich, powerful men win over the “girl next door” through money and status, Chinese regulators are now stepping in to curb exaggerated plots featuring the so-called “dominant CEO” (霸道总裁) archetype, signaling stricter oversight for the booming short drama market.

- ☕ A popular Beijing coffee chain calling itself “People’s Cafe” (人民咖啡馆), with its style and logo evoking nationalist visual nostalgia, has changed its name after facing criticism for building its brand – including pricey coffee and merchandise – on Mao era and state-media political connotations. The cafe is now ‘Yachao People’s Cafe’ (要潮人民咖啡馆).

- 👀 Parents were recently shocked to see erotic ads appear on the Chinese nursery rhymes and children’s learning app BabyBus (宝宝巴士), which is meant for kids ages 0–8. BabyBus has since apologized, but the incident has sparked discussions about how to keep children safe from such content.

- 🧧The 2026 holiday schedule has continued to be a big topic of conversation as it includes a 9-day long Spring Festival break (from February 15 to February 23), making it the longest Lunar New Year holiday on record. The move not only gives people more time for family reunions, but also gives a huge boost to the domestic travel industry.

Hasan Piker’s Chinese Tour & The US–China Content Honeymoon

Livestreamer Hasan Piker during his visit to Tiananmen Square flag-rising ceremony.

It’s not time for the end-of-year overviews just yet – but I’ll already say that 2025 was the US–China ‘honeymoon’ year for content creation. It’s when China became “cool,” appealing, and eye-grabbing for young Western social media users, particularly Americans. The recent China trip of the prominent American online streamer Hasan Piker fits into that context.

This left-wing political commentator also known as ‘HasanAbi’ (3 million followers on Twitch, recently profiled by the New York Times) arrived in China for a two-week trip on November 11.

Piker screenshot from the interview with CGTN, published on CGTN.

His visit has been controversial on English-language social media, especially because Piker, known for his criticism of America (which he calls imperialist), has been overly praising China: calling himself “full Chinese,” waving the Chinese flag, joining state media outlet CGTN for an interview on China and the US, and gloating over a first-edition copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao (the Little Red Book). He portrays China as heavily misrepresented in the West and as a country the United States should learn from.

Hasan Piker did an interview with CGTN, posing with Li Jingjing 李菁菁.

During his livestreaming tour, Hasan, who is nicknamed “lemonbro” (柠檬哥) by Chinese netizens, also joined Chinese platforms Bilibili and Xiaohongshu.

But despite all the talk about Piker in the American online media sphere, online conversations, clicks, and views within China are underwhelming. As of now, he has around 24,000 followers on Bilibili, and he’s barely a topic of conversation on mainstream feeds.

Piker’s visit stands in stark contrast to that of American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins), who toured China in March. With lengthy livestreams from Beijing to Chongqing, his popularity exploded in China, where he came to be seen by many as a representative of cultural diplomacy.

IShowspeed in China, March 2025.

IShowSpeed’s success followed another peak moment in online US–China cultural exchange. In January 2025, waves of foreign TikTok users and popular creators migrated to the Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu amid the looming TikTok ban.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against Trump and US policies. In a playful act of political defiance, they downloaded Xiaohongshu to show they weren’t scared of government warnings about Chinese data collection. (For clarity: while TikTok is a made-in-China app, it is not accessible inside mainland China, where Douyin is the domestic version run by the same parent company).

The influx of foreigners — who were quickly nicknamed “TikTok refugees” — soon turned into a moment of cultural celebration. As American creators introduced themselves, Chinese users welcomed them warmly, eager to practice English and teach newcomers how to navigate the app. Discussions about language, culture, and societal differences flourished. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor. It was a rare moment of social media doing what we hope it can do: connect people, build bridges, and replace prejudice with curiosity.

Some of that same enthusiasm was also visible during IShowSpeed’s China tour. Despite the tour inevitably getting entangled with political and commercial interests, much of it was simply about an American boy swept up in the high energy of China’s vibrant cities and everything they offer.

Different from IShowSpeed, who is known for his meme-worthy online presence, Piker is primarily known for his radical political views. His China enthusiasm feels driven less by cultural curiosity and more by his critique of America.

Because of his stances — such as describing the US as a police state — it’s easy for Western critics to accuse him of hypocrisy in praising China, especially after a brief run-in with security police while livestreaming at Tiananmen Square.

Seen in broader context, Piker’s China trip reflects a shift in how China is used in American online discourse.

Before, it was Chinese ‘public intellectuals’ (公知) who praised the US as a ‘lighthouse country’ (灯塔国), a beacon of democracy, to indirectly critique China and promote a Western modernization model. Later, Chinese online influencers showcased their lives abroad to emphasize how much ‘brighter the moon’ was outside China.

In the post-Covid years, the current reversed: Western content creators, from TikTok influencers to political commentators, increasingly use China to make arguments that are fundamentally about America.

Between these cycles, authentic cultural curiosity gets pushed to the sidelines. The TikTok-refugee moment in early January may have been the closest we’ve come in years: a brief window where Chinese and American users met each other with curiosity, camaraderie, and creativity.

Hasan’s tour, in contrast, reflects a newer phase, one where China is increasingly used as a stage for Western political identity rather than a complex and diverse country to understand on its own terms. I think the honeymoon phase is over.

“Liu Sihan, Your School Uniform Ended Up in Angola”: China’s Second-Hand Clothing in Africa

A Chinese school uniform went viral after a Chinese social media user spotted it in Angola.

“Liu Sihan, your schooluniform is hot in Africa” (刘思涵你的校服在非洲火了) is a sentence that unexpectedly trended after a Chinese blogger named Xiao Le (小乐) shared a video of a schoolkid in Angola wearing a Chinese second-hand uniform from Qingdao Xushuilu Primary School, that had the nametag Liu Sihan on it.

The topic sparked discussions about what actually happens to clothing after it’s donated, and many people were surprised to learn how widely Chinese discarded clothing circulates in parts of Africa.

Liu Sihan’s mother, whose daughter is now a 9th grader in Qingdao, had previously donated the uniform to a community clothing donation box (社区旧衣回收箱) after Liu outgrew it. She intended it to help someone in need, never imagining it to travel all the way to Africa.

In light of this story, one netizen shared a video showing a local African market selling all kinds of Chinese school items, including backpacks, and people wearing clothing once belonging to workers for Chinese delivery platforms. “In Africa, you can see school uniforms from all parts of China, and even Meituan and Eleme outfits,” one blogger wrote.

When it comes to second-hand clothing trade, we know much more about Europe–Africa and US–Africa flows than about Chinese exports, and it seems there haven’t been many studies on this specific topic yet. Still, alongside China’s rapid economic transformations, the rise of fast fashion, and the fact that China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of textiles, the country now has an enormous abundance of second-hand clothing.

According to a 2023 study by Wu et al. (link), China still has a long way to go in sustainable clothing disposal. Around 40% of Chinese consumers either keep unwanted clothes at home or throw them away.

But there may be a shift underway. Donation options are expanding quickly, from government bins to brand programs, and from second-hand stores to online platforms that offer at-home pickup.

Chinese social media users posting images of school/work uniforms from China worn by Africans.

As awareness grows around the benefits of donating clothing (reducing waste, supporting sustainability, and the emotional satisfaction of giving), donation rates may rise significantly. The story of Liu Sihan’s uniform, which many found amusing, might even encourage more people to donate. And if that happens, scenes of African children (and adults) wearing Chinese-donated clothes may become much more common than they now are.

Laojunshan: New Hotspot in Cold Winter

Images from Xiaohongshu, 背包里的星子, 旅行定制师小漾

Go to Zibo for BBQ, go to Tianshui for malatang, go to Harbin for the Ice Festival, cycle to Kaifeng for soup dumplings, or head to Dunhuang to ride a camel — over recent years, a number of Chinese domestic destinations have turned into viral hotspots, boosted by online marketing initiatives and Xiaohongshu influencers.

This year, Laojunshan is among the places climbing the trending lists as a must-visit spot for its spectacular snow-covered landscapes that remind many of classical Chinese paintings. Laojunshan (老君山), a scenic mountain in Henan Province, is attracting more domestic tourists for winter excursions.

Xiaohongshu is filled with travel tips: how to get there from Luoyang station (by bus), and the best times of day to catch the snow in perfect light (7–9 AM or around 6–6:30 PM).

With Laojunshan, we see a familiar pattern: local tourism bureaus, state media, and influencers collectively driving new waves of visitors to the area, bringing crucial revenue to local industries during what would otherwise be slower winter months.

WeChat New Features & Hong Kong Police on Douyin

🟦 WeChat has been gradually rolling out a new feature that allows users to recall a batch of messages all at once, which saves you the frantic effort of deleting each message individually after realizing you sent them to the wrong group (or just regret a late-night rant). Many users are welcoming the update, along with another feature that lets you delete a contact without wiping the entire chat history. This is useful for anyone who wants to preserve evidence of what happened before cutting ties.

🟦The Hong Kong Police Force recently celebrated its two-year anniversary on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), having accumulated nearly 5 million followers during that time. To mark the occasion, they invited actor Simon Yam to record a commemorative video for their channel (@香港警察). The presence of the Hong Kong Police on the Chinese app — and the approachable, meme-friendly way they’ve chosen to engage with younger mainland audiences — is yet another signal of Hong Kong institutions’ strategic alignment with mainland China’s digital infrastructure, a shift that has been gradually taking place. The anniversary video proved popular on Douyin, attracting thousands of likes and comments.

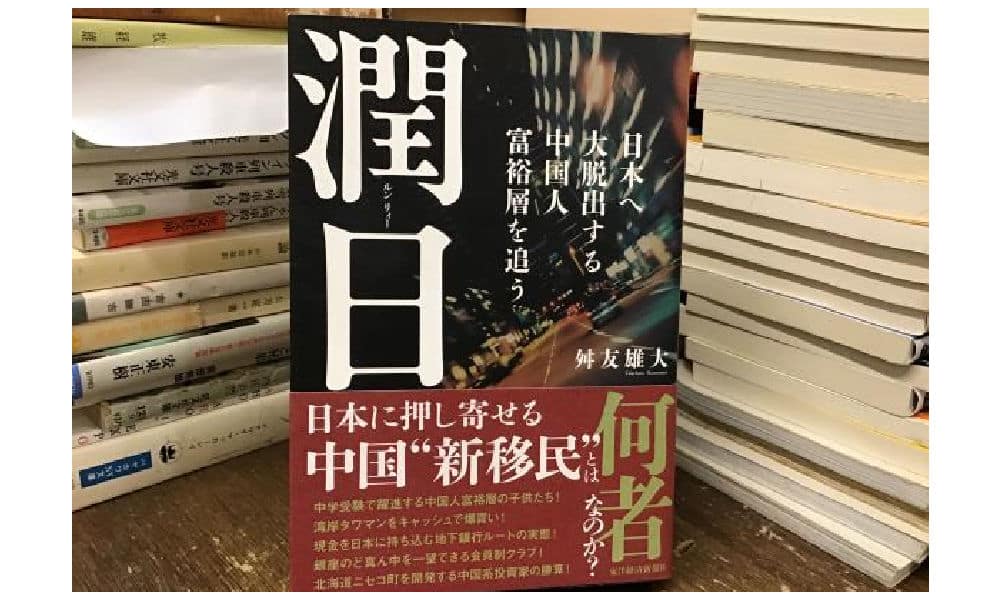

Why Chinese Elite Rùn to Japan (by ChinaTalk)

Over the past week, Japan has been trending every single day on Chinese social media in light of escalating bilateral tensions after Japanese PM Takaichi made remarks about Taiwan that China views as a direct military threat. The diplomatic freeze is triggering all kinds of trends, from rising anti-Japanese sentiment online and a ban on Japanese seafood imports to Chinese authorities warning citizens not to travel to Japan.

You’d think Chinese people would want to be anywhere but Japan right now — but the reality is far more nuanced.

In a recent feature in ChinaTalk, Jordan Schneider interviewed Japanese journalist & researcher Takehiro Masutomo (舛友雄大) who has just published a book about Japan’s new Chinese diaspora, explaining what draws Chinese dissidents, intellectuals, billionaires, and middle-class families to Tokyo.

The book is titled Run Ri: 潤日 Following the Footsteps of Elite Chinese Escaping to Japan (only available in Japanese and Traditional Chinese for now). (The word Rùn 润/潤, by the way, is Chinese online slang and meme expresses the desire to escape the country.)

A very interesting read on how Chinese communities are settling in Japan, a place they see as freer than Hong Kong and safer than the U.S., and one they’re surprisingly optimistic about — even more so than the Japanese themselves.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China Signals. For fast-moving trends and deeper dives, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you just so happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

A small housekeeping note:

This Eye on Digital China newsletter is co-published for subscribers on both Substack and the main site. If you’re registered on both platforms, you’ll receive duplicate emails — so if that bothers you, please pick your preferred platform and unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Trend Watch

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

From quick scrolls to the discussions that matter, these are the topics trending in China this week.

Published

7 days agoon

November 16, 2025

🔥 China Trend Watch — Week 45-46 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to the Eye on Digital China newsletter. It has been an especially tumultuous week on Chinese social media: from the crisis triggered by Takaichi’s remarks to the Nexperia clash and the near-total blackout surrounding the Yunnan “wild child” case. Despite their differences, all of these stories share a common thread — mistrust, whether on the geopolitical stage or at home in institutions and state media.

Thank you for the kind reactions I received after the last newsletter, in which I took a bird’s-eye view of China’s evolving social media landscape and announced a soft goodbye to What’s on Weibo (if you haven’t read it yet, you can find it here).

I’m very grateful to everyone who has followed my journey with What’s on Weibo, and I’m excited to start this new chapter together.

Under the Eye on Digital China newsletter, you can expect updates in three categories: fast-moving trends, slower-burn signals, and longer thematic explorations — plus the occasional personal story, including from the road as I travel through China. (I’ll soon be covering roughly 3,000 miles across the country, so I’m sure I’ll run into plenty worth sharing.)

This is the China Trend Watch edition — a quick catch-up on real-time conversations. Let’s dive in.

- 🔺 A new 32-country survey by The Economist and GlobeScan found a sharp increase in the share of respondents who prefer China over the US as the world’s “leading power,” and younger people are driving much of this shift.

- 🛵 As Ele.me (China’s No.2 food-delivery platform) rebrands to “Taobao Flash Delivery” (淘宝闪购), competitor Meituan used it as the perfect marketing moment by bidding farewell to its long-time competitor with a virtual “memorial service,” complete with “farewell coupons.”

- 👀 Famous Chinese author and Nobel laureate Mo Yan (莫言) made his debut on the social media app Xiaohongshu this week, with a meme-ready video and posts. He’s been praised as a “meme king” for quickly adapting to the app’s community — gaining over 950,000 followers in just five days.

- 🏳️🌈 Two of China’s most popular gay apps, Blued and Finka (翻咔), have been removed from from Apple App Store in China as at the request of Chinese internet regulatory authorities. Last month, Blued – which has over 40 million registered users in China – temporarily suspended new user registrations after media reports accused the platform of facilitating encounters that led to HIV infections among minors.

- 🏆 A remarkable moment during the Golden Rooster Awards went viral after Ne Zha 2 won the award for Best Art Film — yet no one came to pick it up. Director Jiaozi (饺子) had already announced earlier in the year that he and his entire team would be too busy working on Ne Zha 3 to attend any events — and he, very clearly, is a man of his word.

- 🔻 Chinese-Canadian celebrity Kris Wu (吴亦凡), convicted in 2022 for rape and sentenced to 13 years in prison, keeps reappearing in online discussions — but only through rumors. This week, speculation about his possible death in prison spread across social media yet again (“What, did he die again?” some joked). Local authorities have denied the rumors.

1. Sino-Japanese Tensions Escalate After Takaichi’s Taiwan Remarks

Political cartoon circulating on Chinese social media, made by Jun Zhengping (钧正平), official social media name/persona used by the People’s Liberation Army.

With the recent appointment of conservative politician Sanae Takaichi (高市早苗) as the new prime minister of Japan, seen as the ideological successor to Shinzo Abe, many expected renewed Sino-Japanese tensions due to her stances on various sensitive bilateral issues, from wartime history to Taiwan. But perhaps few expected relations to escalate so quickly and so intensely.

This week, Japan and Takaichi have been top trending topics after she made provocative remarks during a hearing in the Diet about potential military intervention in Taiwan-related matters, suggesting Japan’s Self-Defense Forces could exercise the right of collective self-defense if such a situation were recognized as “survival-threatening.” She is also pushing defense-related policy changes, including exploring revisions to Japan’s “three non-nuclear principles.”

The remarks have set off a chain of events — and online trends — marking what may be the worst flare-up in ties since 2012, when major anti-Japanese protests erupted in China following Japan’s purchase of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Chinese officials are sharpening their tone, issuing angry and escalatory diplomatic statements via X, domestic social media, and Foreign Ministry press briefings.

The recent escalations have also led to official warnings about safety risks for Chinese nationals in Japan. On Sunday, China’s Ministry of Education advised Chinese citizens to exercise caution when planning study-abroad arrangements in Japan.

Beyond nationalist discourse and general anti-Japanese sentiment on Chinese social media — and users vowing not to travel or study there — many discussions are also focusing on geopolitics and history rather than consumer boycotts. Well-known nationalist knowledge blogger Pingyuan Gongzi Zhao Sheng (@平原公子赵胜) posted a lengthy post on Weibo (crossposted to Xiaohongshu) suggesting that Japan is filled with ‘deadly energy’ (死气 sǐqì) – acting irrationally and aggressively because it is in complete decline — socially, economically, technologically, and militarily — but unable to accept it. He argues that a strong and stable country would never gamble its future like this, and that only a “zombie-like” nation in denial would provoke China unnecessarily. A related hashtag about Japan’s gloomy status-quo (#日本死气#) has also been used by other commentators across social media.

2. New Updates in Yunnan’s “Wild Child” Case Raise More Questions

Last month, I wrote about a distressing case involving a 3-year-old boy from Nanjian County (南涧县) in Yunnan who was seen walking on all fours, behaving dog-like with possible spinal deformities, naked and apparently neglected by his parents. Several netizens recorded the scene, and videos quickly spread online in mid October, with thousands referring to the boy as the “wild child” (野孩子 or “naked child” 赤裸小孩) of Yunnan and demanding that authorities intervene and hold the parents accountable.

What followed was a wave of confusing — and sometimes contradictory — media reports. Some outlets initially claimed the boy’s parents were impoverished and struggling, while others reported they were well-educated and financially stable, framing their dubious parenting approach as a deliberate and philosophical “lifestyle choice.”

The parents, who live a camper-van lifestyle, turned out to both hold university degrees (the mother even holds a post-graduate degree). They claimed they practice “natural education” (自然教育法) and said their son disliked wearing clothes because of eczema. Some reports said they refused to cooperate with local authorities; others said they agreed to stop letting their child crawl around naked. Neither the 3-year-old nor his younger brother had ever been registered for a household hukou (registered permanent residence), raising further concern.

Online, speculation intensified. Many netizens feared the child was being deliberately mistreated for profit, suggesting a dark-web content industry behind the scenes.

This week, local authorities and state media posted a new update, releasing a video of the boy — referred to as Pingping (平平, an alias) — walking and playing normally. According to officials, the parents are now receiving support and guidance in raising their children, and both boys are being issued official household registrations by local authorities. The investigation, they said, found no evidence that the parents were involved in “illegal online profit-making.”

But many netizens are anything but convinced. They argue the child shown in the video isn’t the same boy — his face is blurred, and his voice appears overdubbed. Posts questioning the official narrative are being censored. And although authorities say the case is now closed, with the family under ongoing guidance, many people online feel the story is anything but over, and that the real truth still hasn’t surfaced.

Some of the doubts about the veracity of the story and videos are being expressed in more subtle ways to avoid censorship. One Weibo commenter simply wrote that “mild spinal deformities in a 3-year-old may improve within 3–6 months through corrective treatment (…) while recovery from severe deformities may take 1–2 years or even longer” — subtly suggesting that it would be impossible for the boy to be walking and playing normally now if he had shown signs of spinal deformity just weeks earlier. On Douyin, users also questioned what happened to the supposedly severe eczema that had allegedly prevented the boy from wearing clothes. A Zhihu writer expressed frustration: “The official report is extremely fake, but there’s no way to talk about it.” Another commenter echoed the sentiment: “People today aren’t stupid. Even if you forbid them to speak, do you think they won’t know something is wrong?” For many, the case is troubling not only because of the child’s situation, but because the official handling of it has reinforced a growing sense that the public is being managed rather than informed.

3. Nexperia and Dutch ‘Pirate Gene’ Discussions

It wasn’t just bilateral relations with Japan that took a hit this week — tensions between China and the Netherlands have also deepened due to the ongoing dispute surrounding Dutch intervention in the chipmaker Nexperia. This is an issue I wrote about last month. After the incident made international headlines, China responded by blocking the export of Nexperia chips from its factory in China, putting major European automakers at risk of running short on critical components for vehicle electronics.

In brief: Nexperia (安世半导体), a Dutch semiconductor company based in Nijmegen and wholly owned by the Chinese conglomerate Wingtech (闻泰科技) since 2019, became the center of a major diplomatic clash after the Dutch government reportedly ordered a one-year freeze on strategic and governance changes within the company on September 30. Citing national security concerns and a desire to secure domestic chip production, the Dutch move came amid reports that Nexperia CEO Zhang Xuezheng was relocating production facilities and sensitive technology from Europe to China.

While tensions had previously seemed to ease, the conflict escalated again this week. The Dutch public broadcasting organization reported on a widening rift as Nexperia China accused the Dutch branch of disrupting production by refusing to send chip components to the Dongguan factory. Meanwhile, Nexperia Netherlands claimed the Chinese side had been urging customers to reroute payments away from the Netherlands and into Chinese bank accounts. A Dutch delegation is expected to travel to Beijing next week to discuss the situation and attempt to break the deadlock.

On Chinese social media, many users view the Dutch actions as an unfair use of a Cold-War-era law to target a modern, legally operating multinational company. The move is widely seen as another example of Western countries shifting rules to maintain technological dominance when faced with strong competition from Chinese firms. As a result, what began as a company-specific dispute has grown into a broader geopolitical struggle over global chip control and economic sovereignty.

Modern Opium [当代鸦片] (dāngdài yāpiàn)

Over the past year, the term “modern opium” has become more common on Chinese social media— used as a popular term to promote food or other products. It’s perhaps not unlike the famous “finger-licking good” slogan in the West, but applied far more broadly, also to refer to “addictive” online accounts, collector toys, or restaurants. In fact, it has become so commonplace that you can now find “modern-opium food recommendation” suggestions on platforms when searching for good places to eat in major Chinese cities.

Recently, the term began trending as a controversial expression after Chinese media focused on an official online complaint arguing that it “turns national trauma into entertainment” (将民族伤痛娱乐化) and trivializes a painful chapter of Chinese history, drawing a direct connection to the Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860).

The complaint has put the term at the center of public attention — but how controversial is it, really? While Chinese media are eager to highlight how inappropriate the phrase is, given China’s collective memory of the “century of humiliation,” many Xiaohongshu users nevertheless seem to think it’s perfectly acceptable to describe their newfound addiction to a milky drink, a sweet dessert, or the perfect hotpot. (I can relate to the latter.)

During this year’s Single’s Day Shopping Festival (11.11), “Europe” was a popular item on shopping lists, not for its fashion or chocolate, but for anti-theft tools. Using “Europe is not safe” slogans and real footage of pickpockets in action, hundreds of Taobao sellers promoted handy anti-theft accessories for Chinese tourists traveling abroad, some even labeled for specific countries, from Spain to Germany.

This year’s shopping festival reportedly generated 1.695 trillion RMB ($238B) across platforms — still up 14.2% year-on-year, but with far slower growth than in previous years (2024: 26.6% growth). Jing Daily noted a noticeably more negative social media vibe surrounding the festival, with young consumers on Xiaohongshu growing more skeptical and questioning its purpose. Gen Z users are prioritizing timeless purchases over trend cycles and embracing more practical spending (like gadgets to avoid getting robbed in Europe).

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China China Trend Watch. For slower-moving trends and deeper structural analysis, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or

email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral4 months ago

China Memes & Viral4 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained