China Insight

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

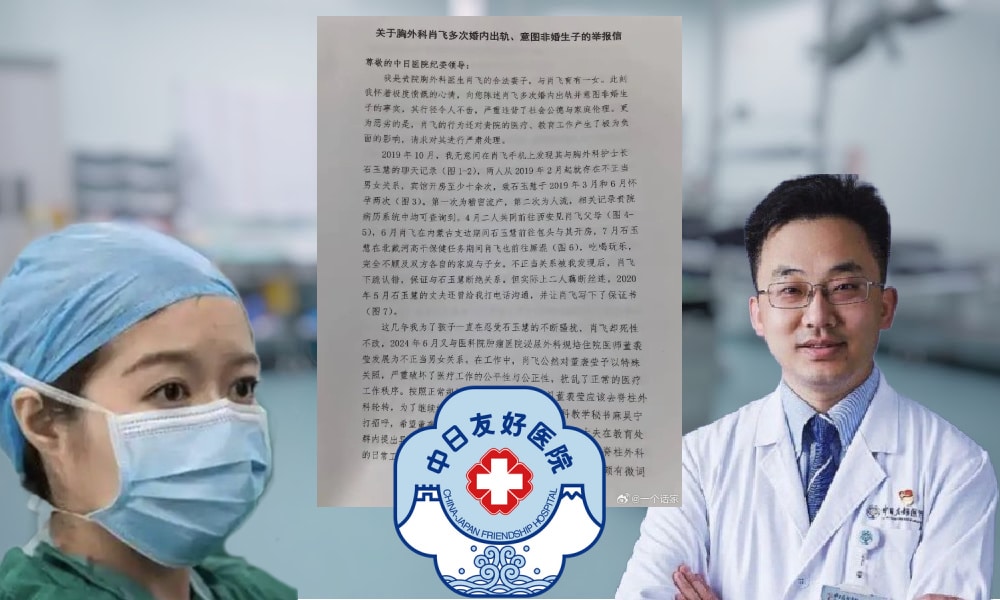

Behind the scandal at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital: the doctor, the trainee, and the letter that took over the Chinese internet.

Published

3 months agoon

FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Dear Reader,

A controversy that has been brewing recently has completely taken over the Chinese internet over the past week, becoming the biggest public scandal on Chinese social media in 2025 so far.

At the center of it all is Dr. Xiao Fei, a well-known thoracic surgeon at the prestigious China-Japan Friendship Hospital in Beijing who has come under fire in the medical world following revelations that he cheated on his wife with a head nurse, a trainee, and others.

This may sound like a Chinese version of an episode of Grey’s Anatomy, but it goes far beyond messy relationships alone and reveals serious social concerns and exposes deeper systemic problems involving academic and medical institutions.

To understand how this unfolded, I’ll walk you through the main people involved, the events that led up to it, and the key issues that turned this medical controversy into a nationwide talking point.

Main People Involved

👨⚕️ Xiao Fei (肖飞): associate chief thoracic surgeon at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital (中日友好医院) in Beijing, with a PhD in surgery from Peking University’s medicine department. He had worked at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital since 2012, rising from resident doctor to associate chief surgeon, and was selected for the hospital’s “Elite Program” (菁英计划). He also served as a graduate advisor at Peking Union Medical College (北京协和医学院). A former Communist Party member, he was awarded the title of “Outstanding Communist Party Member” (优秀共产党员) at the hospital in 2020. Xiao is the central figure in the scandal involving multiple affairs and professional misconduct. Born in 1986 and a native of Shaanxi.

The main people involved: Gu Xiaoya (lower left) and Xiao Fei, and Shi Yuhui (top left) and Dong Xiying.

👩⚕️ Gu Xiaoya (谷潇雅): associate chief ophthalmologist at Beijing Hospital. Legal wife of Xiao Fei and mother to their daughter. She also holds a PhD in clinical medicine from Peking University. She is the “whistleblower” who exposed the scandal through a detailed letter and supporting material backing up her claims. Native Beijinger.

👩⚕️ Shi Yuhui (石玉慧): head nurse of the thoracic surgery department at China-Japan Friendship Hospital. She began an affair with Xiao Fei in early 2019—both were married at the time. During their relationship, she became pregnant twice and miscarried both times. Despite interventions of her own husband and Xiao’s wife, she maintained contact with Xiao and allegedly harassed Gu Xiaoya through 2024. Born in 1981.

👩⚕️ Dong Xiying (董袭莹): former urology resident at China-Japan Friendship Hospital. Studied economics at Barnard College in New York (graduated in 2019), then earned her medical doctorate through the “4+4” clinical medicine program at Peking Union Medical College (北京协和医学院). Currently serves as a resident physician at the Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. She comes from a privileged background: her father is an executive at a state-owned enterprise; her mother is a vice president at the University of Science and Technology Beijing (北京科技大学). She began a relationship with Xiao in 2024 and is reportedly pregnant with his child, due in June.

From One Letter to Nationwide Concern

This story first started to gain traction within various circles on Chinese social media since around April 21, when a long letter written by Gu Xiaoya (谷潇雅), the legal wife of the renowned surgeon Xiao Fei, was widely circulated, from WeChat to Weibo and Zhihu and beyond.

Soon, Chinese media outlets picked up the story, causing it to snowball and going trending on social media. The first time it trended on Weibo was on Sunday, April 27.

✉️ The letter that started it all

Gu’s letter, dated April 18, 2025, was addressed to the Disciplinary Committee at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital in Beijing. In the letter and attached materials, Gu Xiaoya details how her husband had been cheating on her since 2016 — including exact dates, locations, and chat records to support her claims.

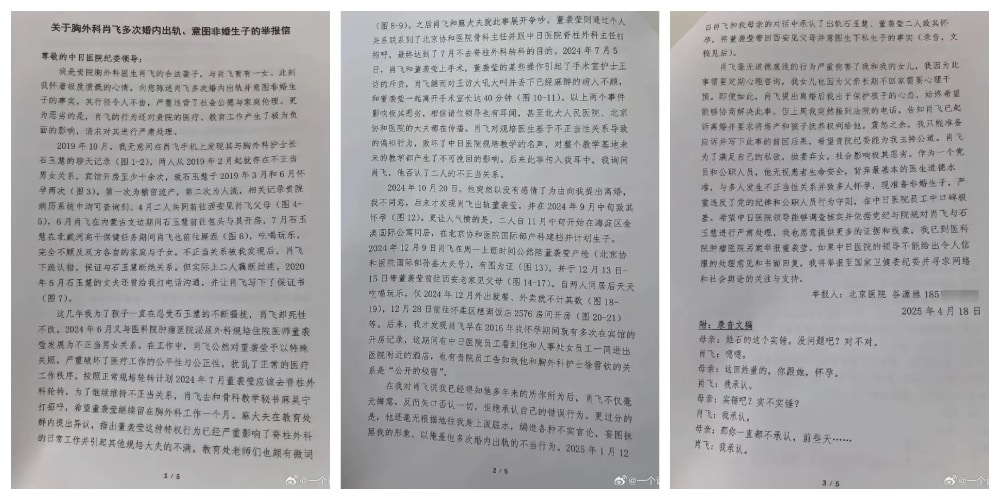

First part of Gu’s letter

She writes that she wanted to report her husband’s extramarital affairs, as well as his apparent intent to have a child out of wedlock, because she believed his behavior “seriously violated social morality and professional ethics, and had a profoundly negative impact on both the hospital and the education of medical students.”

Gu explains that she first discovered Xiao Fei’s infidelity when she checked his phone in October 2019 and uncovered his secret affair with Shi Yuhui (石玉慧), a head nurse in his department, with whom he had been involved since at least February of that year. The two would also stay in hotel rooms together during trips, some work-related. According to Gu — and backed by hospital records — Shi became pregnant twice in 2019, both pregnancies ending in miscarriages.

Gu says that efforts to stop the affair were fruitless, even when Shi’s own husband was involved in trying to end the affair, and that Shi Yuhui continued to harass Gu for years afterward.

However, in June 2024, while on duty in the operating room, Xiao began another new affair — this time with Dong Xiying, a urology resident physician. Their relationship developed quickly. According to her medical training schedule, Dong was supposed to move on to another department in July 2024, but Xiao allegedly intervened to ensure she remained in thoracic surgery.

During this period, Gu claims that during a surgery on July 5, 2024, Xiao Fei had a dispute in the operating room involving his affair partner, Dong Xiying, and a nurse. As a result, Xiao left the operating room with Dong (allegedly to comfort her), even though a patient had already been anesthetized and was lying on the operating table. They were gone for 40 minutes, during which the anesthetist and nurse were left to manage the patient alone.

Gu mentions that medical staff involved in or aware of the operation later raised concerns in internal group chats or reported the incident directly to the hospital’s education or supervisory offices.

In a screenshot of the Surgical Anesthesia Department Nurses Group, one nurse said:

💬 “First thing in the morning, Xiao Fei was chaotic – he completely lost his temper on a phone call, tore off his surgical gown, and left the operating room. He called Zhang Ying (张颖) angrily saying if the circulating nurse wasn’t replaced, he would cancel the surgery. He then unfastened the scrubs of the trainee doctor Dong, and left with her. The surgery was left undone! They had just connected the electrosurgical unit when Xiao left with the trainee doctor, leaving the anesthetized patient lying in the OR. There is no doctor present during surgical time!”

In October 2024, Xiao filed for divorce. Gu later discovered that he was already living with Dong Xiying, who had become pregnant the previous month.

Gu also learned that Xiao had been involved in other affairs dating back to 2016, when Gu was pregnant with their daughter, and that he would stay at different hotels with various female members of staff and nurses.

She claims she initially hoped to avoid legal action, but Xiao’s threats to seek full custody of their daughter pushed her to expose his affairs and seek justice.

💥 Far-reaching consequences

On April 27 – the day this topic dropped in Weibo’s top trending lists – the China-Japan Friendship Hospital issued an official statement to respond to the controversy. The hospital confirmed that the allegations involving their staff member Dr. Xiao were basically true (#中日友好医院通报肖某问题属实#). They suspended Xiao while investigating the matter.

Soon, one statement after another, news reports and hashtags followed. Dr. Xiao was expelled from the Communist Party, his profile was removed from the hospital’s website, and his employment was terminated.

Around April 30, public attention began shifting toward Dong Xiying (董袭莹) and her academic credentials. The young physician, who graduated from Barnard College in New York with a degree in economics, entered the “4+4” MD/PhD medical training program at Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) in 2019. Within a few years, she was praised as a model student within the 4+4 track (non-medical undergraduate + 4 years medical training).

Netizens soon discovered that PUMC had been quietly removing articles from its website related to Dong. Her PhD thesis disappeared from public databases, and her name was edited out of the President’s Commencement Address. As more details about her privileged background surfaced, growing doubts emerged about her qualifications and how she gained admission to the program.

It is rumored that Dong has now left China for the US.

The hospital has not yet released details on how – and if – Shi Yuhui will be dealt with.

On May 1st, China’s National Health Commission announced an official investigation into the matter, looking into the allegations against Xiao and also reviewing the academic and work history of Dong Xiying.

The scandal has caused something of an earthquake — not just within medical circles, but also in academic ones, and across the internet at large, where netizens are particularly concerned about the broader social issues this story touches on.

Some netizens made mindmaps of the scandal to explain who the main persons nvolved are and what the key issues are. Shared by Qiao Kaiwan on Weibo.

There are many layers to this story, and perhaps more yet to be uncovered. One popular Weibo blogger (Qiao Kaiwan @乔凯文) commented about the scandal, and the role played by Dong Xiying:

💬 “(..) it’s rare for a central figure in a single case to touch on five major socially sensitive issues all at once: educational fairness (教育公平), doctor-patient trust (医患信任), marital fidelity (婚姻忠诚), class solidification [lack of upward mobility] (阶层固化), and academic corruption (学术腐败)…”

At its core, public concern centers around various major themes that are all tied to deeply rooted cultural values or long-standing social issues. Since there is some overlap within these topics, I’ll focus on three main values vs concerns here.

1. Fairness in Education & Corruption in Academia

Fairness and corruption within China’s education system are recurring hot social topics. Education is widely regarded as the main path to upward mobility, which makes the system fiercely competitive—starting as early as kindergarten. The pressure to succeed in the gaokao college entrance exams begins years before the tests are actually taken.

Most Chinese parents are willing to invest heavily in their children’s education, driven by the fear that their kids will fall behind. This intense competition is reflected in the popularity of the term nèijuǎn (内卷), “involution,” which describes a situation where students (or professionals) must overwork and go above and beyond just to keep up with peers. Everyone ends up standing on their toes to keep pushing the bar—yet no one moves forward (read more about this here).

Especially in such a competitive system, where entire families invest so much time, energy, and resources into helping younger generations succeed, academic corruption is a sensitive issue that affects trust in the entire system and exacerbates common people’s disillusionment with meritocracy. Yet academic corruption—ranging from plagiarism and data manipulation to power abuse and favoritism—has been a widespread and increasingly discussed problem in mainland China since the 1990s.

Central to the current controversy surrounding Xiao Fei and Dong Xiying is the “4+4 program,” an experimental and relatively new medical education model inspired by the American system. Unlike China’s traditional path (five years of undergraduate study in medicine followed by three years of graduate training), this program allows students to complete four years of non-medical undergraduate education, followed by four years of medical training. It’s a fast track in which students can begin practicing medicine after just one year of residency instead of three. It was originally intended to create opportunities for talented individuals who decide to pursue medicine later on in their academic careers.

It sounds good in theory, but many feel that the program—with its high undergraduate standards and required letters of recommendation—essentially serves as a “backdoor” into medicine for the elite. Only a small number of applicants are admitted: the quota for both the 2025 and 2026 cohorts at PUCM is just 45 students.

Online, many are questioning whether Dong really met the proper standards for admission. How could someone with an economics degree from a liberal arts college become a so-called “medical talent” in just a few years? In contrast, people have pointed to Chen Ruyue (陈如月), a finance graduate from the prestigious Peking University who was also passionate about medicine and applied for the same program, but was rejected. Netizens wonder, “Where is the fairness in medical education?”

Many suspect Dong benefited from privileged access via family connections—her mother Mi Zhenli (米振莉) is a vice president at the University of Science and Technology Beijing (USTB), and her father Dong Xiaohui (董晓辉) is a senior executive at a state-owned enterprise.

Suspicions deepened when people discovered that Dong’s PhD supervisor, the orthopedic academician Qiu Guixing (邱贵兴), had no connection to her research field. Her clinical trajectory involves many different areas, from gynecological imaging and internal medicine to thoracic surgery and urology, a seemingly patchy path that raised further questions because this “magical and legendary swift crossovers between medical fields”of Dong could supposedly only mean that she is either an “unprecedented genius” or that her stardom medical rise was faciliated by “countless invisible hands” (comments by popular Weibo blogger @庚白星君).

There’s more that’s raised eyebrows.

Dong’s academic publishing history shows that she authored eleven research papers over a period of three years across various disciplines, from orthopedics to gynecology and urology. There are doubts over the exact role played by Dong in some of these studies. Dong was still a resident at the lowest level with relatively little experience, yet was able to publish bladder cancer diagnosis and treatment guidelines—she was listed as the first author on three English-language papers about bladder cancer clinical guidelines. Some allege that her contributions, like translating Chinese guidelines to English, do not merit a first-author mention.

There are also concerns about plagiarism. Claims have emerged that Dong’s 2023 doctoral thesis shows significant similarities to an invention patent submitted in 2022 by several professors and Zhao Jihuai (赵基淮), a hearing-impaired graduate student from the University of Science and Technology Beijing (USTB), who is mentored by Professor Ban Xiaojuan (班晓娟), Dong’s aunt.

It also does not help that PUMC, once promoting Dong as a success story, has now deleted related articles from its site and edited her name out of the President’s Commencement Address that mentioned her.

Concerns about Dong’s academic background and the apparent bending of rules inevitably also cast a shadow over the medical institutions where she trained. According to Gu’s letter, Dong was expected to rotate through various departments as part of her residency. However, instead of moving on to spinal surgery after completing her thoracic surgery rotation, she was allowed to remain—allegedly due to personal connections and pressure from Dr. Xiao—even though the hospital’s education team had initially objected.

If true, this could not only point to routine abuses of power within the medical training systems, but also creates unease over how qualified doctors such a Dong actually are, which also affects the trust patients place in hospitals.

2. Trust Between Patients and Doctors & Medical Negligence

The main incident in this scandal that has sparked widespread controversy is the moment when Dr. Xiao reportedly left the operating room together with Dong for an entire 40 minutes during a surgery, leaving the anesthetized patient on the table.

The idea that even a chief doctor such as Xiao can violate medical ethics by leaving a surgery mid-procedure for 40 minutes deepens fears about medical professionalism.

Trust between patients and doctors and worries over medical negligence are recurring topics on Chinese social media. There have been dozens of incidents that previously went viral showing how some doctors abuse or scam patients, or put commercial interests above the health of their patients. Some stories that gained nationwide attention in previous years include an anesthesiologist from Shandong who live-streamed while a patient was undergoing gynecological surgery, or a young patient who was asked to pay more money while already undergoing a surgery.

Such distrust in doctor-patient relations flared up again in light of this incident, in which a sedated patient was, against all protocol, left on the operating table mid-surgery—allegedly due only to a quarrel between another nurse and Xiao’s mistress that made him angry.

Xiao has given two media interviews in response to the allegations. Regarding the claim that he stormed out of the operating room with Dong, leaving a patient behind, he reportedly stated that he was not gone for 40 minutes, but for a maximum of 20 minutes to calm down after a dispute.

Although Xiao has admitted to inappropriate relationships with a head nurse and a training resident physician (refuting allegations of affairs with other nurses or members of staff), he firmly denied more serious allegations involving medical safety.

In an interview with Jiupai News, he said:

💬 “I have clear supporting evidence that around 9 AM, I left the operating table after an argument. I left to coordinate, not to ‘demand.’ I coordinated with a senior staff member in the operating room about whether it would be possible to replace the circulating nurse under these circumstances. Then I went upstairs to measure my blood pressure, drink some water, and take some blood-pressure medication. After calming down a bit, I immediately returned to the OR. I believe this was entirely reasonable. In fact, I was precisely concerned about the patient’s safety. Before I left, I gave specific instructions to the nurse at the table. Our anesthesiologist was present as well, and their professional competence is fully sufficient to ensure the safety of a patient who had not yet undergone any surgical procedure.”

Regardless of the circumstances, the fact that Xiao Fei left an anesthetized patient during surgery is not only one of the reasons that cost him his job—it’s also one of the reasons why he has temporarily become the most hated doctor in China among the public.

The fact that he tried to defend his actions only seemed to aggravate public opinion against him: “So he thinks 20 minutes is a short time to leave a surgery?” some say; “completely outrageous,” “a serious threat to patient safety.”

“Xiao is morally bankrupt,” another commenter wrote: “He is still trying to make excuses for leaving the OR mid-surgery. As chief surgeon he seriously violated his professional values. Not only doesn’t he reflect, he doesn’t even have remorse.”

3. Moral Integrity & Marital Infidelity

In the end, this entire scandal started because Xiao was caught cheating with multiple women at his workplace. That alone is seen as a lack of moral integrity and a violation of professional ethics, which are also tied to corruption and power abuse.

In China’s corruption cases, extramarital affairs often serve as red flags — not every official with a mistress is corrupt, but most corrupt officials do have one.

One of the most high-profile public cases involving an extramarital affair was in 2023, when Chinese official Hu Jiyong (胡继勇), who held a high-ranking position at PetroChina, was caught walking hand in hand with his mistress by a TikTok photographer during a work trip to Chengdu.

Chinese state media wrote that “being a Communist Party of China member, Hu has moral obligations, which he transgressed by having an alleged extramarital affair.”

Hu Jiyong was dismissed from his positions as executive director, general manager, and Party Committee secretary. His mistress, coincidentally also a Miss Dong, also lost her job at the company. For Xiao Fei and Dong Xiying, the exposure of their illicit affair might have even more serious repercussions.

In the end, Gu’s letter had a major impact on everyone involved. Xiao’s actions not only carried serious consequences for Gu and their young daughter, but also ended his career, affected both Dong Xiying and Shi Yuhui and their families, and damaged the reputations of the China-Japan Friendship Hospital and PUMC.

The entire scandal is not really about Xiao or Dong anymore. It is about the entire system around them that facilitated their affair and made it possible to bend the rules and engage in unethical and unprofessional behavior.

On May 5, Chinese political commentator and columnist Sima Pingbang (@司马平邦), who has 7 million followers on Weibo, wrote: “What I think of the Xiao Fei and Dong Xiying incident: The academic authorities behind them must be brought down!”

Meanwhile, despite the serious concerns behind the scandal, plenty of people are also just enjoying the online spectacle. Some performers are even incorporating the story of Xiao and Dong into their comedy shows. It’s not Grey’s Anatomy — it’s actually much more dramatic, and hasn’t even reached its final episode yet…

Thanks to Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang for their input and contributions to this newsletter.

Also, welcome to the new premium members of What’s on Weibo! Please know that I’m always open to suggestions—if you spot any noteworthy trends you’d like to learn more about, don’t hesitate to reach out. I always enjoy receiving your emails. It’s great to see the subscriber community growing.

That said, What’s on Weibo still needs to expand its member base to cover all costs and keep subscription prices as they are. If you enjoy one of our articles, this newsletter, or the site in general, please spread the word (or consider gifting a subscription to someone who might love it too)!

Best,

Manya

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Thanks to Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang for their input and contributions to this newsletter.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Insight

The Secret Life of Monks: Shi Yongxin’s Shaolin Scandal Casts a Shadow on Monastic Integrity

“To put it bluntly, temples have been places of deception, corruption, opportunism, and exploitation since ancient times.”

Published

7 days agoon

July 28, 2025

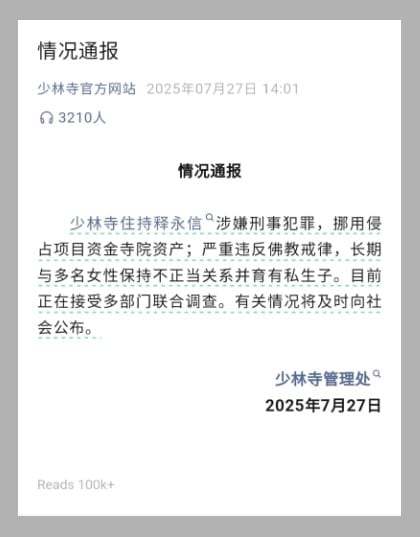

This week, news about a well-known Chinese monk going off the Buddhist path has triggered many discussions on Chinese social media.

The story revolves around Shi Yongxin (释永信), the head monk at China’s famous Shaolin Temple (少林寺) in Dengfeng, Henan. Shi is suspected of embezzlement of temple funds and illicit relationships, and is currently under investigation.

In recent days, wild rumors have been circulating online claiming that Shi fled to the United States after being exposed. On July 26, a supposed “police bulletin” began circulating, alleging that Shi Yongxin had attempted to leave the country with seven lovers, 21 children, and six temple staff. It also claimed he was stopped by authorities before exiting China, that he had secretly obtained U.S. citizenship a decade ago, and that he had misused donations and assumed fake identities.

Although that specific report has since been refuted by Chinese official media, it quickly became clear that there was real fire behind all that smoke.

The report that circulated online and was later confirmed to be fake

Because despite all the sensationalized gossip (some posts even claimed Shi had 174 illegitimate children!), what’s certain is that Shi Yongxin seriously crossed the line. On July 27, 2025, the Shaolin Temple Management Office (少林寺管理处) issued an official statement through its verified channels, including its WeChat account. The statement read:

The report that circulated online and was later confirmed to be fake.

Shi Yongxin, the Abbot of Shaolin Temple, is suspected of criminal offenses, including misappropriating and taking project funds and temple assets. He seriously violated Buddhist discipline, maintained improper relationships with multiple women over a long period and fathered illegitimate children. He is currently under joint investigation by multiple departments. Relevant information will be made public in due course.

Shaolin Temple Management Office

July 27, 2025

China’s Buddhist Association (中国佛教协会) also released a statement on July 28, in which it stated that, in coordination with the Henan Provincial Buddhist Association (河南省佛教协会), Shi Yongxin has been officially stripped of his monastic status.

Various Chinese media sources report that Shi Yongxin was taken away by police on Friday, July 25. Chinese media outlet Caixin suggests that it must not have come as a complete surprise, since Shi had allegedly already been restricted from leaving the country since around the Spring Festival period (late January 2025) (#释永信春节前后已被限制出境#).

About Shi Yongxin

Shi Yongxin is not just any abbot. He’s the abbot of the Shaolin Monastery (少林寺), which is one of the most famous Buddhist temples in the world and is known as the birthplace of Shaolin Kung Fu. The temple was founded in 495 CE. Besides being a Buddhist monastery, it also operates as a popular tourist attraction, a kung fu school, and a cultural brand.

Shi has been running the monastery for 38 years, a fact that also went trending on Weibo these days (#释永信已全面主持少林寺38年#, 140 million views by Monday).

Shi Yongxin is the monastic name of Liu Yingcheng (刘应成), born in Yinshang county in Fuyang, Anhui, in 1965. He came to Shaolin Temple in 1981 and became a disciple of abbot Shi Xingzheng (释行正), who passed away in 1987. Shi Yongxin then followed in his footsteps and managed the temple affairs. He formally became head monk in 1999.

Moreover, Shi Yongxin reportedly served as President of the Henan Provincial Buddhist Association since 1998 and as Vice President of the Buddhist Association of China since 2002.

Shi Yongxin, photos via Weibo.

Shi Yongxin was thus an incredibly powerful figure—not only because of the decades he spent overseeing temple affairs, but also due to his influence within public, institutional, and religious spheres.

Holding such a visible role, Shi Yongxin (释永信) also had (or has—though it’s unlikely he’ll ever post again) a Weibo account with over 882,000 followers (@释永信师父). His last post, made on July 24, was a Buddhist text about the ‘Pure Land’ (净土)—a realm said to make the path toward enlightenment easier.

That post has since attracted hundreds of replies. While some devoted followers express disbelief over the scandal, many others respond with cynicism, questioning whether anything about Buddhism remains truly ‘pure.’

One widely shared post shows an artist sitting in front of a painting of Shi Yongxin, writing, “Worked on this painting for six months, just finished late last night—feels like the sky’s collapsed.” The second picture, posted by someone else, says, “Just change it a bit.”

One aspect of the scandal fueling online discussions is the fact that Shi Yongxin had led the monastery for so long. Rumors about his “chaotic private life” and unethical behavior surfaced years ago, going back to at least 2015 (#释永信10年前就曾被举报私生活混乱#; #释永信曾被举报向弟子索要供养钱#). One of the questions now echoing across social media is: why wasn’t he held accountable sooner? “Who was protecting him?”

“The Tip of the Iceberg”

The Shi Yongxin scandal does not just hurt the reputation and cultural brand of the Shaolin Monastery; it also damages a certain image of Buddhist monks as a collective of people with true faith and integrity.

According to well-known knowledge blogger Pingyuan Gongzi Zhao Sheng (@平原公子赵胜), many people’s understanding of abbots or Buddhist masters (“方丈大师们”) is flawed, since it’s generally believed they attained their high positions within the monasteries due to their moral virtue or deep understanding of Buddhism. In reality, Zhao Sheng argues, these individuals often rise to power because they are skilled at earning money and gaining influence.

“To put it bluntly,” Zhao Sheng writes, “temples have been places of deception, corruption, opportunism, and exploitation since ancient times.”

The blogger argues that much of the influence and power of Buddhist masters was stripped away under Mao Zedong, but that some new famous monks rose in the 1980s, using their skills and connections to rebuild temples and turn them into thriving enterprises.

“If you want to find a few people in temples who truly have faith, who truly have personal integrity, and who are truly dedicated to saving all living things, it’s not that they don’t exist—but it’s rather difficult, like finding a needle in a haystack,” Zhao Sheng wrote.

Some commenters suggest that Shi Yongxin is just the tip of the iceberg (“冰山一角”). They believe that if someone as influential as him can be involved in such misconduct—despite whistleblowers having tried to expose him for over a decade—there must be many more cases of power abuse and corruption within China’s monasteries.

“I previously donated money to the temple,” one commenter on Xiaohongshu wrote: “Although it wasn’t much, it does make me a bit uncomfortable now.”

Another person posted that the Shi Yongxin scandal gave them a sense of despair.

Some older posts about the extravagant lifestyles of head monks — including their luxury cars — have also resurfaced online and are once again making the rounds, suggesting that netizens are actively revisiting other potential instances of misconduct within the monastic world.

Abbot Guangquan Fashi (光泉法师) with a Ferrari California T, Kaihao Fashi (开豪法师) with a Porsche Panamera, Shi Yongxin (释永信) linked to an Audi Q7, and Huiqing (慧庆) and a BMW 7 Series.

One image that resurfaced online shows Shi Yongxin—allegedly driving an Audi Q7—alongside other abbots, such as Guangquan Fashi (光泉法师), the head monk of Lingyin Temple (灵隐寺), who is associated with a Ferrari.

More images like these are now circulating, as people delve into the ‘secret lives of monks’ beyond the spiritual, shifting focus to their material lives instead.

Monks from major temples, including Qin Shangshi (钦尚师) of Famen Temple, E’erdeni (鄂尔德尼) of Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, Yin Le (印乐) of Baima Temple, and Huiqing (慧庆) of Baishou Temple, are rumored to be associated with high-end cars like BMWs, a Porsche Cayenne, and a Range Rover.

While the results of the investigation into Shi Yongxin are still pending, many netizens are already looking beyond him. One person writes: “Are you realizing now? It’s not just Shaolin Temple that has money, other temples aren’t exactly short on money either.”

Another person wonders: “Are the monks in today’s temples actually still truly devoted to spiritual practice at all?”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

Something In the Water: How Yuhang’s Smelly Water Went from Odor Incident to Trust Crisis

“Tap water safety is a barometer of a city’s level of civilization.”

Published

1 week agoon

July 25, 2025

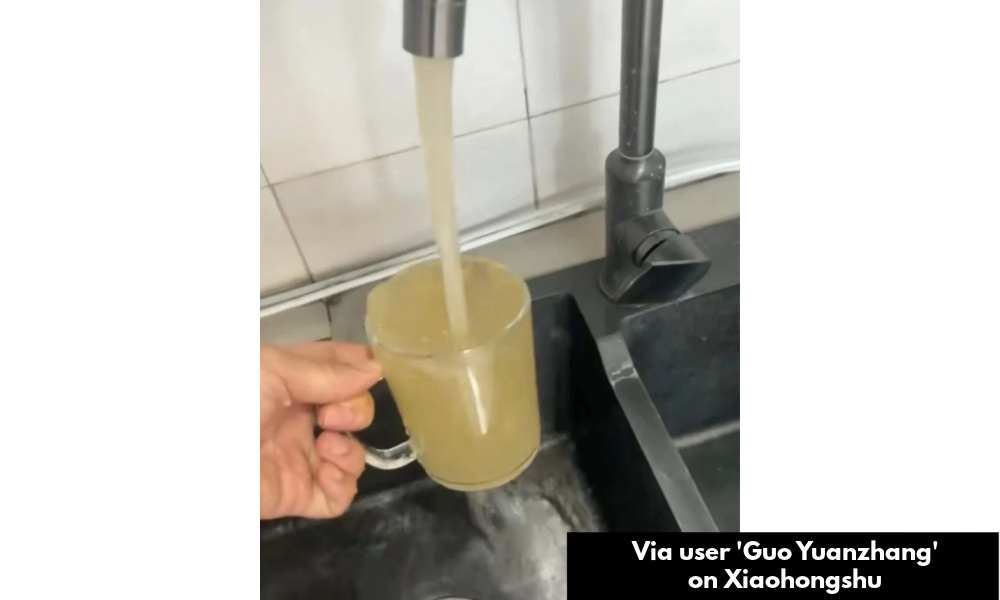

On July 16, locals in Yuhang (余杭), a district of Hangzhou, noticed something fishy about their running water. It had turned brown and smelled unpleasant.

From residential compounds in Liangzhu to Renhe Street (良渚街道–仁和街道), some residents complained that their water smelled like “dead rats,” while others thought it resembled the odor of sewage, and later started smelling like disinfectant or other chemicals.

Soon, rumors began to spread that there was poop in the water, sparking panic among residents from Yuhang and beyond, especially because no official bulletin had been released explaining what was wrong with their tap water, despite its strange color and scent.

Worried about what was in the water, many people refrained from bathing, cooking, or cleaning, and rushed to supermarkets to stock up on bottled water.

The incident became known among netizens as the “Hangzhou Stinky Water Incident” (杭州臭水事件).

Later that same day, the water utility company stated that the quality of the main pipeline water had been restored, recommending local communities and residents to flush out the pipes and let the faucets run for up to 30 minutes to get rid of residual water.

In some neighborhoods, however, the water remained brown for some time – perhaps due to water tanks that had not been thoroughly cleaned yet.

Even days after, on July 24 and also later, locals posted on social media about the water being yellowish or leaving brownish residue on white cloths inside the sink. Videos posted online showed that the run on bottled water continued after July 16.

“They say it’s ok for us to use,” one commenter said: “But how can ordinary people like us actually use it?!”

Algae in the Water, Officials Punished

On July 19, official media reported that preliminary findings linked the water issues to algae contamination. Yuhang authorities issued an apology, and the water company announced it would waive 5 tons of water fees per household—roughly 20 yuan ($2.8) (or about the price of a takeaway milk tea, which many suggested) (hashtag: #余杭水务承诺为臭水用户免5吨水费#).

Nearly a week after residents first started noticing a problem with their water, an official report on the issue was finally released on July 23, following an investigation launched by Hangzhou authorities.

The report confirmed that the extremely warm weather had indeed led to rapid algae growth in the water bodies near the intake point of the Renhe Water Plant (人和水厂) on the Dongtiaoxi (东苕溪) River, which supplies treated drinking water to Hangzhou and nearby areas.

After recent rainfall and runoff, algae and their breakdown products (which include foul-smelling sulfur compounds) accumulated near the intake and entered the plant in the early hours of July 16. After discovering the issue that morning, the water company quickly switched to a new water source.

Following the incident, the relevant water authorities conducted a city-wide inspection and found that all water plants met national standards, with no harmful bacteria such as E. coli detected.

Nevertheless, the Hangzhou municipal authorities concluded that the response to the water crisis was flawed on multiple levels. The water supply company, for instance, failed to promptly notify residents, while the district government was slow in coordinating the response and reporting it to city-level authorities.

In total, seven local officials were formally held accountable for their handling of the incident. Some received official warnings, while others faced more serious consequences, including the Deputy General Manager of the Yuhang Environmental Protection Science and Tech Company (under the Yuhang Water Group), who was removed from his position and expelled from the Party.

Awakening a Trust Crisis That Already Existed

On Chinese social media, the entire “stinky water incident” has been trending for days. The anger isn’t just about the algae itself, but more about how officials handled the situation: the delay in informing residents, the late investigation, and the media machine that echoes the official line.

It’s also because this is about running water — the lifeline of any city. It’s what you bathe in, cook with, and wash your child with. It crosses the boundary between public infrastructure and private life.

One post on Xiaohongshu called tap water safety “a barometer of a city’s level of civilization” (“自来水安全是城市文明的试纸”).

Multiple people felt that they weren’t — and still aren’t — getting the right information about what is wrong with their water. One Weibo commenter wrote:

“In our country, you absolutely do not want to let your child major in journalism. Just look at news media organizations nationwide, including state-run media, which one is actually truly fulfilling their journalistic responsibilities? Every time a social incident happens, all the news outlets do is forward official notices and they’re not doing any on-site news investigation reports. Take the recent lead poisoning incident, or the Yuhang tap water case as examples. At first, all the reports were just reposts of local government notices. Later, when local officials were arrested, the updates again just came from forwarded investigation team reports.

Earlier this month, the Tianshui lead scandal also made headlines after more than 250 children in a kindergarten in Tianshui, Gansu Province, were poisoned after staff used industrial pigments to color food, some containing over 20% lead and far exceeding safety limits.

The Yuhang stinky water incident isn’t introducing new fears, but rather awakening a trust crisis that already existed. It’s sharpening public awareness around food and water safety, and fueling skepticism toward the official narratives and media reports that follow.

On July 23, residents in Rizhao’s Wulian County also reported murky tap water in their homes and posted videos about it.

According to some Chinese media reports, the problems with the muddy tap water in Rizhao – like in Hangzhou – also related to the hot weather. One spokesperson reportedly stated that water levels in the reservoirs wa dropping quickly. Combined with low water pressure, this led to water quality problems in the pipes and supply lines. Some neighborhoods reportedly have no water at all.

“How can unqualified water even enter the pipes?” some concerned netizens asked.

“Is this the beginning of a water crisis?” others wonder.

Despite the seriousness of the situation, some commenters joked: “They saw Hangzhou trending and felt competitive, and wanted to make the hot search lists too.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Waiting for Karma in the Maskpark Scandal

The Secret Life of Monks: Shi Yongxin’s Shaolin Scandal Casts a Shadow on Monastic Integrity

Six Chinese Students Dead After Falling Into Flotation Tank During Mine Visit

Something In the Water: How Yuhang’s Smelly Water Went from Odor Incident to Trust Crisis

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

Behind the Mysterious Death of Chinese Internet Celebrity Cat Wukong

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

Earring Gate: Huang Yangdiantian and the 2.3 Million RMB Emerald Earrings

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral3 weeks ago

China Memes & Viral3 weeks agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature9 months ago

China Books & Literature9 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Society10 months ago

China Society10 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World12 months ago

China World12 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media

Pingback: What the “4+4” Medical Scandal Reveals About Second-Generation Privilege | theTotalStory | Conservative News & Opinion