China Celebs

Zhai Tianlin’s Alleged Plagiarism Triggers Discussions on Academic Cheating in Chinese Universities

“Colleges and Universities face great corruption problems, that is what you should be looking into.”

Published

7 years agoon

By

Gabi Verberg

Earlier this month, Chinese actor Zhai Tianlin (翟天临) drew the public’s attention for his appearance at the CCTV Spring Festival Gala, where he starred as a police officer preventing his parents from being scammed. Now, Zhai, again, is at the center of attention: not for his acting skills, but for allegedly committing academic fraud.

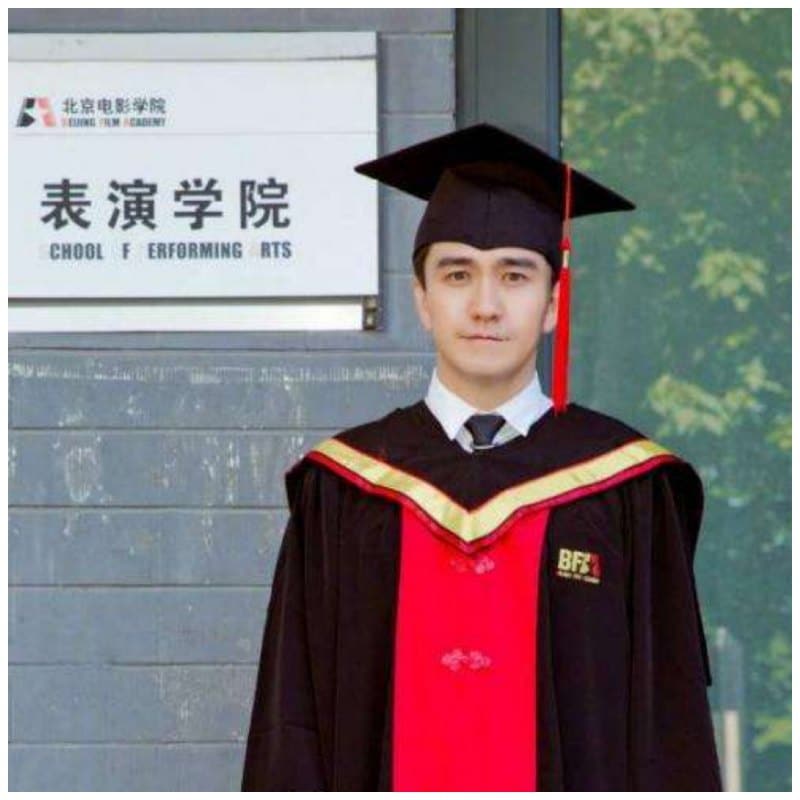

The famous actor is a Beijing Film Academy Ph.D. graduate and postdoctoral candidate at Peking University, one of China’s most renowned universities.

His alleged academic misconduct has been a topic of discussion for some days now. During a live broadcast with fans, Zhai apparently said he did not know what CNKI (知网) is, an academic database that all scholars in China will be familiar with.

It led to suspicions on Zhai’s academic standing, and people on the Quora-like Q&A platform Zhihu accused Zhai of not publishing any academic papers in recognized scholarly journals – something that is mandatory for Ph.D. students in China in order to fulfill their graduation requirements.

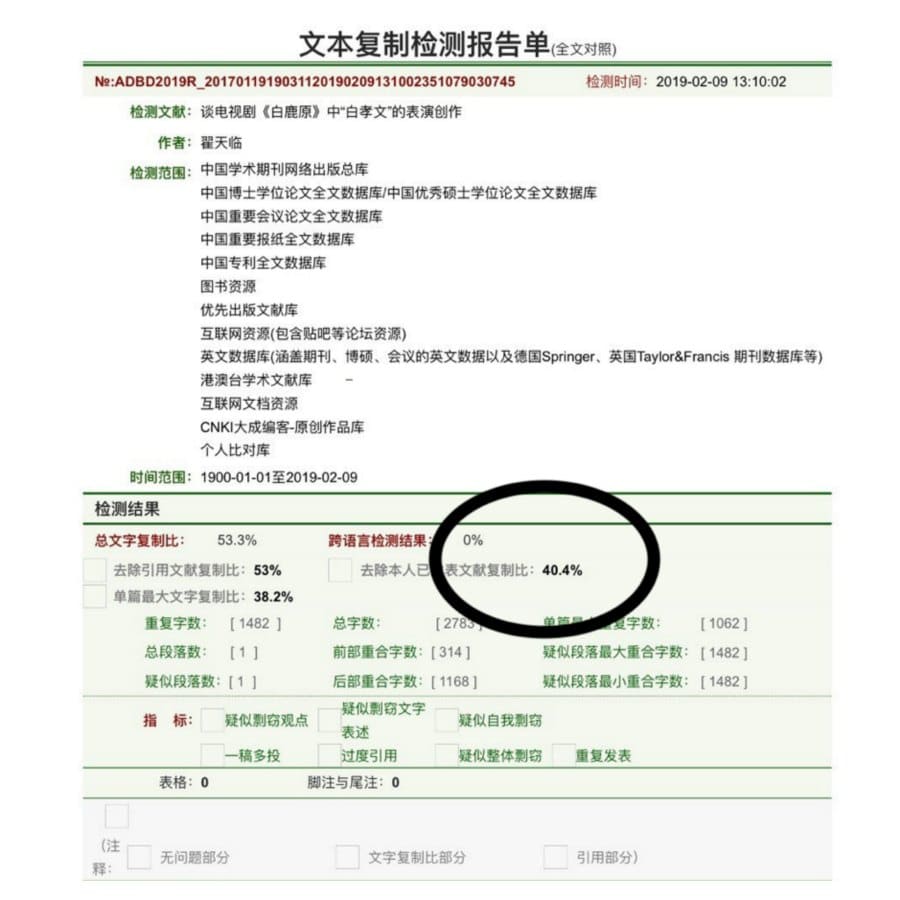

Zhai’s academic records increasingly became the focus of attention on February 9th, when one Weibo user (PITD亚洲虐待博士组织), a graduate student from Beijing, posted the results of a plagiarism detection test that was run on one of Zhai’s papers.

The test result revealed that of the 2783 words used in the paper, that was published last year, 1482 words were copied from other texts, indicating a 40.4% similarity score.

After the Beijing Film Academy released a statement that they would be investigating Zhai Tianlin, state media outlet China Daily posted a message on their Weibo account, stating that “academic standards must be the same for everyone” and that “postdoctoral researchers are a university’s greatest honor, ” and that “who wants to carry the crown should also carry the weight.”

On that same day, Peking University also published a statement saying that they are investigating the incident.

Zhai Tianlin (1987), who is also known as Ronald Zhai, is most known for starring in various popular Chinese TV shows and dramas, such as White Deer Plain and The Advisors Alliance.

The plagiarism allegation case has become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media this week. The hashtag “Peking University Responds to Zhai Tianlin Case” (#北大回应翟天临事件#) has been viewed a staggering 650 million times on Weibo at time of writing, while the hashtag “Beijing Film Academy Sets Up Zhai Tianlin Investigation Team” (#北电成立翟天临事件调查组#) received more than 490 million views.

The storm is not likely to blow over soon, as new reports now also allege that Zhai’s MA-thesis relies heavily on the scholarly work of Chen Kun, a famous Chinese actor who also attended the Beijing Film Academy.

Although the scandal has triggered countless reactions condemning Zhai, there are also many people on social media who are directing their anger towards the universities and state media, with one typical comment saying: “By solely focusing on Zhai, you are avoiding the real problem. Colleges and universities face great corruption problems, that is what you should be looking into.”

Another person wrote: “I feel like the public opinion is focused too much on this case of ‘academic misconduct.’ What the media should be investigating is: why was the paper not checked for plagiarism before its publication? What the Beijing Film Academy should be looking into is how somebody can graduate with a paper that is not up to standard? And how someone who clearly doesn’t hold the appropriate academic abilities has access to its programme.”

“Peking University and Beijing Film Academy are both responsible for this fraud. How could they ever enroll such a fraudulent person?!” others wrote.

Some commenters seem to have no trust in China’s academic standard, saying: “Are you telling me you [the universities] didn’t know about this when you admitted him? Now you are setting up investigation teams, but it is all just for show.”

Academic corruption in the Chinese educational context has been a well-known problem for years. As early as 2002, the Ministry of Education implemented various policies to combat academic misconduct, defining it as an act of academic dishonesty that is punishable, but the problem is still widespread (Kai 2012).

Some studies suggest that one of the factors that play a role in plagiarism in China relate to the fact that ‘plagiarism’ is something that is often defined in very general terms, with university handbooks nor policies clearly codifying instances of “appropriate and inappropriate source use” (Hu & Lei 2015, 236).

There are also many other factors at play, however, such as the pressure for doctorate students to publish their papers, and the phenomenon of “publishing cash incentives,” which would allegedly trigger more academic fraud.

On Chinese social media, many people express that they hope that the institutions involved will “set an example” for other universities and “be transparent” in the way they’ll handle Zhai in case he is found guilty of plagiarism.

Many also pointed out the irony in the fact that it was Zhai who played the police officer that prevented his parents from being scammed during the CCTV New Years’ Eve Gala.

“This is just all so embarrassing,” some write: “Now it looks like not just Zhai’s PhD status should be taken from him, but also his MA title.”

Others suggest that this whole scandal would make an excellent topic for another TV drama, starring Zhai Tianlin, doing what he does best: acting. Some voices suggest that people should wait for the investigations into Zhai’s work to be completed before condemning him. With the massive online attention for this case, it might not take too long for more facts to surface on the case. We’ll keep you updated.

By Gabi Verberg and Manya Koetse

References

Hu, Guangwei and Jun Lei. 2015. “Chinese University Students’ Perceptions of Plagiarism.” ETHICS & BEHAVIOR 25(3): 233–255.

Kai, Ren. 2012. “Fighting against Academic Corruption: A Critique of Recent Policy Developments in China.” Higher Education Policy (25): 19–38.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Gabi Verberg is a Business graduate from the University of Amsterdam who has worked and studied in Shanghai and Beijing. She now lives in Amsterdam and works as a part-time translator, with a particular interest in Chinese modern culture and politics.

China Celebs

China Trend Watch: Quiet Nationalism, Loud Statements, and Nanjing Memorial Day

From war memory to viral eggs, salty cakes, an unfortunate dinner party and farewell to an iconic actress.

Published

4 weeks agoon

December 14, 2025

🔥 China Trend Watch — Week 50 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to the Eye on Digital China newsletter. This is the China Trend Watch edition — a quick catch-up on real-time conversations.

I’ve rounded up my latest China trip that brought me from Chongqing to Nanjing, Wuhan, Zaozhuang and Beijing, for some of my research on Chinese remembrances of war. Along the way, I have met many friendly people and had interesting converations, from hanging out with a group of Wuhan teenagers to lively conversations with retired seniors in Shandong.

A small and short personal observation, if I may, regarding the current tensions between China and Japan.

I vividly remember the atmosphere on the streets during earlier moments when tensions ran sky-high—most notably in 2012, after a major diplomatic crisis erupted over Japan’s nationalization of several disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. That episode triggered large-scale anti-Japanese protests across China and spilled unmistakably into everyday life. In Beijing’s Sanlitun area, for instance, there was a street food vendor who put up a large sign proclaiming, “The Diaoyu Islands belong to China.” In the hutong neighborhoods, it seemed as though virtually every household had hung a Chinese flag by its door. Books about Japan that I purchased locally later turned out to have entire pages ripped out. My favorite sushi restaurant suddenly displayed a sign explaining that its brand was, in fact, very Chinese and had nothing to do with Japan. Nearby, in the clothing markets around the Beijing Zoo, T-shirts bearing nationalistic slogans related to the islands dispute were on sale at multiple stalls.

By contrast, during my most recent stay in Nanjing and beyond—despite the increasingly militant tone of state media and social media campaigns surrounding Japan, and despite the undeniable persistence of anti-Japanese sentiment—I noticed far fewer visible expressions of it in daily life. There were no slogan T-shirts, no banners, no overt street-level signaling. While news came out that a string of Japanese performances in China were canceled, I noticed hotel waitress fully dressed in a Japanese kimono at an in-house Japanese restaurant. Local bookstores are filled with works by Japanese authors, and Japanese popular culture appear to be thriving and coexisting comfortably with China’s own flourishing ACG (anime, comics, and games) industry.

Is there simply less anti-Japanese sentiment than over a decade ago? Or is it, perhaps, that in today’s highly digitalized Xi Jinping era, nationalist narratives are more tightly managed and increasingly channeled online—making people more cautious, more restrained, or simply less inclined to express political sentiments openly in public space?

A cab driver in Chongqing told me he believed there was “something wrong” with Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi and the influence she has had on bilateral relations since her rise to power. While supporting his government’s tough stance and expressing sadness over the scars left by war, he also mentioned that he had enjoyed a pleasant conversation earlier that same morning with a young Japanese man he had driven to the train station.

“We didn’t talk about the latest clash,” he said. “If find that too sensitive to mention. He spoke Chinese, he studied Chinese, like you. I don’t hate today’s Japanese people at all. In the end, we’re all just people. What’s happening now is something between the leadership.”

He spoke at length while driving me to the station, signaling that the topic clearly weighed on him. It left me with the sense that the absence of banners or T-shirts does not mean the issue has faded from everyday life, only that it is not expressed as a mass spectacle like it was in earlier years. It has become quieter, more online, and more filtered through official narratives, but it is still very much alive.

There is a lot more to say, but it is Sunday after all, and there is plenty more to read here, so let’s dive in.

- 🍓 Chinese consumers were pretty salty this week when discovering their pricey strawberry cake from Alibaba supermarket chain Hema (盒马) tasted all wrong. Hema acknowledged a production issue (they didn’t say it outright, but salt was allegedly used instead of sugar) and the incident triggered discussions about food safety & quality control in automated food production, especially when such a major mistake happens at high-profile companies.

- 🌡️ China’s announced ban on mercury thermometers (as of Jan 1st 2026) has sparked a buying frenzy, as many consumers, reluctant to switch to electronic alternatives, still prefer mercury models for their perceived accuracy and convenience. Despite nearly half of annual mercury poisoning cases being linked to broken thermometers, prices have now surged from around 4 yuan ($0.6) to over 30 yuan ($4.25), and stores have reported complete sellouts.

- ❄️ Beijing welcomed its first snowfall of winter 2025 this week, leading to lovely social media pics and the Beijing Palace Museum tickets selling out instantly. Experiencing and capturing that first snowfall at the Forbidden City has become somewhat of a holy grail on social media.

- 🕵️♂️ A local construction site in Shanghai unexpectedly became the scene of a modern-day treasure hunt after dozens of residents armed with shovels and metal detectors rushed to the area following online rumors that silver coins (including valuable older ones) had been found. Authorities had to intervene and, while not confirming the rumors, emphasized that any buried cultural relics belong to the state.

- 🇷🇺 Since this month, Chinese citizens can enter Russia visa-free for up to 30 days, a policy that led Chinese state media to claim that “Russia is replacing Japan as a new favorite among Chinese tourists.” On social media, however, the vibe is different, with travelers complaining about high prices, poor internet, lack of online payments, unreliable ATMs, and the need for thorough trip preparation — all reasons why Russia is unlikely to become the go-to destination for the Chinese New Year.

- 🫏 An investigation by Beijing Evening News revealed that many of the capital’s popular donkey meat sandwich shops are actually serving horse meat without informing customers. China’s donkey shortage — driven by declining domestic supply, rising demand for the traditional Chinese medicine Ejiao (which uses donkey hides), and an African export ban — has been a hot topic this year. Now that it’s directly affecting a beloved delicacy, the issue is drawing even more public attention.

1. Why This Year’s Nanjing Memorial Day Felt Different

Posters published by various Chinese state media outlets to commemorate the Nanjing Massacre.

December 13 marked the 88th anniversary of the fall of Nanjing, and this year’s Nanjing Memorial Day (南京大屠杀难者国家公祭日), although described as a low-key commemoration by foreign media, was trending all over Chinese social media.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, on December 12, 1937, the Japanese army attacked Nanjing from various directions, and defending Chinese forces suffered heavy casualties. A day later, the city was captured. It marked the beginning of a six-week-long massacre filled with looting, arson, and rape, during which, according to China’s official data, at least 300,000 residents, including children, elderly, and women, were brutally murdered.

This year, the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Day, which was first officially held as a state-level event in 2014, carried extra weight. This dark chapter of history has continuously been a sensitive topic in Sino-Japanese relations, but with recent diplomatic tensions between the two countries reaching new heights, the Memorial Day was especially tied to current-day relations between China and Japan and to Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who has been described by Chinese media as an “ultranationalist” with tendencies to downplay Japan’s wartime aggression. Takaichi’s November 2025 parliamentary statement that a Chinese military action against Taiwan could be considered a “survival-threatening situation” for Japan, allowing for the deployment of its Self-Defense Forces, continues to fuel Chinese anger.

The link between history and current-day bilateral relations was visible not only on social media, but also during the commemoration itself, where Shi Taifeng (石泰峰), head of the ruling Communist Party’s Organization Department, said that any attempt to revive militarism and challenge the postwar international order is “doomed to fail.”

Besides the many online posters disseminated by Chinese official accounts on social media focusing on mourning, quiet commemoration, and honoring the lives of the 300,000 Chinese compatriots killed in Nanjing, one official online visual stood out for displaying a louder and more aggressive message—namely that posted by the official Weibo account of the Eastern Theater Command of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (@东部战区).

The visual posted by the PLA Eastern Theater Command, titled: Rite of the Great Saber (大刀祭).

The visual showed a strong hand holding a giant blood-stained blade that is beheading a skeleton wearing a helmet marked “militarism,” with images related to the Nanjing Massacre visible on the blade and, behind it, a map of East Asia. The number “300000” appears in red, dripping like blood. At the top, the characters read “Rite of the Great Saber” or “The Great Saber Sacrifice” (大刀祭).

The official account explained the visual, writing: “(…) 88 years have passed and the blood of the heroic dead has not yet dried, [yet] the ghost of militarism is making a comeback. Each year, on National Memorial Day, a deafening alarm is sounded, reminding us that we must—at all times hold high the great saber offered in blood sacrifice, resolutely cut off filthy heads, never allow militarism to return, and never allow historical tragedy to be repeated.”

The text’s “cut off filthy heads” phrasing is similar to part of a now-deleted tweet sent out last month by the Chinese Consul General in Osaka, Xue Jian (薛剑), who responded to Takaichi’s controversial Taiwan remarks by writing (in Japanese): “If you come charging in on your own like that, there’s nothing to do but cut that filthy neck down without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared?” (“勝手に突っ込んできたその汚い首は一瞬の躊躇もなく斬ってやるしかない。覚悟が出来ているのか。”)

The recent visuals, social media approach, and shifts in texts reflect a clear change in tone in Chinese official discourse regarding Japan and the memory of war, moving the narrative from victimhood toward a more confrontational and militant tone.

2. He Qing, China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty”, Passes Away at 61

He Qing. Images on the sides: the four famous roles in China’s most iconic tv dramas.

China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty” (古典第一美女), He Qing (何晴), who starred in all four of China’s most beloved and canonical television dramas, passed away on Saturday at the age of 61. On December 14, news of the famous actress’s passing was trending across virtually all Chinese social media apps.

Born in 1964 into an artistic family in Jiangshan, Zhejiang Province, He Qing received traditional Chinese opera (Kunqu) training at the Zhejiang Kunqu Opera Troupe. Her debut in the entertainment industry may have come by chance, as she reportedly once met Chinese director Yang Jie (杨洁) on a train, which led to her joining the production of Journey to the West (西游记), where she played Lingji Bodhisattva (灵吉菩萨).

In China, He Qing is remembered as a veteran actress in much the same way that some famous Hong Kong actresses became renowned for their beauty, iconic roles, and for essentially becoming household names. More than just glitter and glamour, He Qing was especially a symbol of classical Chinese beauty and literary culture. She was the only actress to star in screen adaptations of all four of China’s “Four Great Classical Novels” (演遍四大名著): besides Journey to the West (西游记, 1986), she also appeared in Dream of the Red Chamber (红楼梦, 1987), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义, 1994), and Water Margin (水浒传, 1998).

She was married to fellow actor Xu Yajun (许亚军), with whom she had a son, Xu He (许何). Although the two later divorced, she remained close to her ex-husband and even befriended his new (and fourth) wife, Zhang Shu (张澍).

In 2015, He Qing was diagnosed with a brain tumor. After her diagnosis, she withdrew from the entertainment industry to focus on her recovery and lived a low-key life in her later years.

Her passing has prompted an outpouring of tributes from Chinese netizens and colleagues in the entertainment industry. Mourning her loss comes with a sense of nostalgia for the past, and many have praised He Qing for her timeless beauty and authenticity, which will be remembered long after her passing.

3. And Then There Were None: Dinner Party of Ten Leaves One Man with the Bill

Ten dine together, nine slip away..one left for the bill, who he refused to pay…

Do you know that nursery rhyme where ten little soldiers disappear one by one until none remain at the end? That is more or less what happened earlier this month in Chongqing, when ten people dined together at a restaurant, but—once it came time to pay—nine people left one by one.

One had to answer a phone call, another had to use the restroom, and in the end, just before midnight, only Mr. Zhang was left, facing a bill of 1,262 yuan ($180), which he refused to pay. He argued that he could not afford it and that the dinner party hadn’t been initiated by him at all; as merely a participant, the bill shouldn’t have been his responsibility.

After the restaurant called the police, the organizer of the dinner was contacted. But he, too, said he couldn’t pay. Through police mediation, Mr. Zhang then wrote a written commitment promising to pay the bill the following day and left his ID as collateral, but he still failed to make the payment.

By now, the restaurant is planning to sue and has also contacted the Chinese media. According to Zhang, who apparently has been unable to contact his “friends” to collect the money: “I did make the promise, but if I pay the money, wouldn’t that make me a sucker?” (“我的确承诺了,但你说我把钱付了,我是不是冤大头啊”)

As the story went completely viral (by now, even Hu Xijin has weighed in) comment sections filled with broader social reflections on alcohol-fueled group gatherings and unclear payment rules, where one person sometimes ends up paying for everything despite feeling it wasn’t their role to do so. In this era of digital payments, many argue it should be easy enough to go Dutch and settle the bill immediately via a group payment app.

Although Zhang is seen by some as a victim, others argue that he is still a “sucker” for not paying after having promised to do so. As one commenter put it: “Out of the ten of them, not a single one is a good person.”

Real Person Vibes [活人感 (huóréngǎn)

Every December, the ten most popular buzzwords, key terms, or expressions of the year are listed by the Chinese linguistics magazine Yǎowén Jiáozì (咬文嚼字), selecting words that reflect present-day society and changing times. Each year, the list goes trending and is widely disseminated by Chinese media.

This week, the 2025 list was released, including terms such as Digital Nomads 数字游民 (shù zì yóu mín), Sū Chāo (苏超), referring to the hugely popular amateur Jiangsu Super League football competition, and “Pre-made ××” (预制, yù zhì), following a year filled with discussions about pre-fab and pre-made food (see article).

My favorite word on the list is “Real-Person Vibes” (活人感 huó rén gǎn). The term literally consists of three characters meaning “living – human – feeling,” and it describes people, stories, or things that feel unpolished, spontaneous, and unfiltered—something that has become increasingly relevant in a year dominated by AI-generated content and visuals.

Amid over-curated feeds and AI-produced text, we crave huóréngǎn: authenticity, small imperfections, and liveliness as an antidote to a digital, artificial world.

The 9:12 Boiled Egg That Took Over Douyin

How do you get a perfect boiled egg? A Douyin user known as “Loves Eating Eggs” (爱吃蛋) has become all the rage after leaving a precise comment on how to boil eggs. His advice: First boil the water, then add the eggs, boil for exactly 9 minutes and 12 seconds, remove, and immediately run under cold water.

That simple tip catapulted his follower count from around 200 to over 3.5 million in a single week (I just checked—he’s up to 4.2 million now).

The new viral hit is a 24-year-old self-proclaimed egg expert (of course, his English nickname should be the Eggxpert). He claims to have eaten 40 eggs a day for the past five years and knows exactly how every second of boiling, frying, or stirring affects an egg. He regularly posts videos showing eggs cooked for different lengths of time.

It has earned him the nicknames “Egg God” (蛋神) and “Boiled Egg Immortal” (煮蛋仙人), and has sent boiled eggs (9 minutes and 12 seconds exactly) all over social media feeds.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China China Trend Watch. For slower-moving trends and deeper structural analysis, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

Housekeeping reminder: if you’re receiving duplicate newsletters, it’s likely because you signed up on both the main What’s on Weibo website and the Eye on Digital China Substack. If you’re a paying member on one of the two, you may receive the premium newsletter twice. Please keep the one you’re paying for, and feel free to unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or

email me. First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Celebs

He Qing, China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty”, Passes Away at 61

He Qing is remembered as a veteran actress, a symbol of classical Chinese beauty and literary culture.

Published

4 weeks agoon

December 14, 2025

🔥China Trend Watch — Week 50 (2025) This text is part of the Eye on Digital China newsletter which was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty” (古典第一美女), He Qing (何晴), who starred in all four of China’s most beloved and canonical television dramas, passed away on Saturday at the age of 61. On December 14, news of the famous actress’s passing was trending across virtually all Chinese social media apps.

Born in 1964 into an artistic family in Jiangshan, Zhejiang Province, He Qing received traditional Chinese opera (Kunqu) training at the Zhejiang Kunqu Opera Troupe. Her debut in the entertainment industry may have come by chance, as she reportedly once met Chinese director Yang Jie (杨洁) on a train, which led to her joining the production of Journey to the West (西游记), where she played Lingji Bodhisattva (灵吉菩萨).

In China, He Qing is remembered as a veteran actress in much the same way that some famous Hong Kong actresses became renowned for their beauty, iconic roles, and for essentially becoming household names. More than just glitter and glamour, He Qing was especially a symbol of classical Chinese beauty and literary culture. She was the only actress to star in screen adaptations of all four of China’s “Four Great Classical Novels” (演遍四大名著): besides Journey to the West (西游记, 1986), she also appeared in Dream of the Red Chamber (红楼梦, 1987), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义, 1994), and Water Margin (水浒传, 1998).

She was married to fellow actor Xu Yajun (许亚军), with whom she had a son, Xu He (许何). Although the two later divorced, she remained close to her ex-husband and even befriended his new (and fourth) wife, Zhang Shu (张澍).

In 2015, He Qing was diagnosed with a brain tumor. After her diagnosis, she withdrew from the entertainment industry to focus on her recovery and lived a low-key life in her later years.

Her passing has prompted an outpouring of tributes from Chinese netizens and colleagues in the entertainment industry. Mourning her loss comes with a sense of nostalgia for the past, and many have praised He Qing for her timeless beauty and authenticity, which will be remembered long after her passing.

Read the entire newsletter here.

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me. First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission — contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

Why Were 100,000 Pregnant Women’s Blood Samples Smuggled Out of China?

When an Entertainment Scandal Gets Political: How Wong Kar-wai Survived a Nationalist Storm

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment6 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment6 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital12 months ago

China Digital12 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

Rob

February 15, 2019 at 4:40 pm

I did research into Chinese Universities and their (lack of) academic policies – not a single University among the top 50 in China had clear written policies. More to the point, the Universities I and friends worked in (USTB, Renmin, UIR, BFSU, UIBE) not only had no policies, but teachers who caught students were not allowed to apply suitable consequences (I caught two Masters students and the Department Head tried to convince me not to fail them).

Zhai’s case is only at issue because he’s highly public; nobodies in China who cheat and plagiarize still manage to get away with it, and University departments permit it and defend students who do it.

Of course, Chinese academia is full of this; there was a scandal in Beijing back in 2010-2011 where a group were translating academic papers into Chinese and selling them to Chinese scholars for publishing; in other cases, Uni profs were stealing their students’ work and publishing it as their own (USTB had a couple of cases of this).

Plagiarism is like any form of corruption in China – it only matters if you get caught in a very public way.