Weiblog

Story of 7-Year-Old Delivery Boy Raises Awareness for China’s Uneducated Migrant Children

Published

8 years agoon

After a young boy from Yunnan went viral on Chinese social media earlier this week for his “icy looks” after walking 4.5 kilometers to school in the freezing cold while his parents are out working in the city, the story of another young Chinese migrant child is now making its rounds on Weibo.

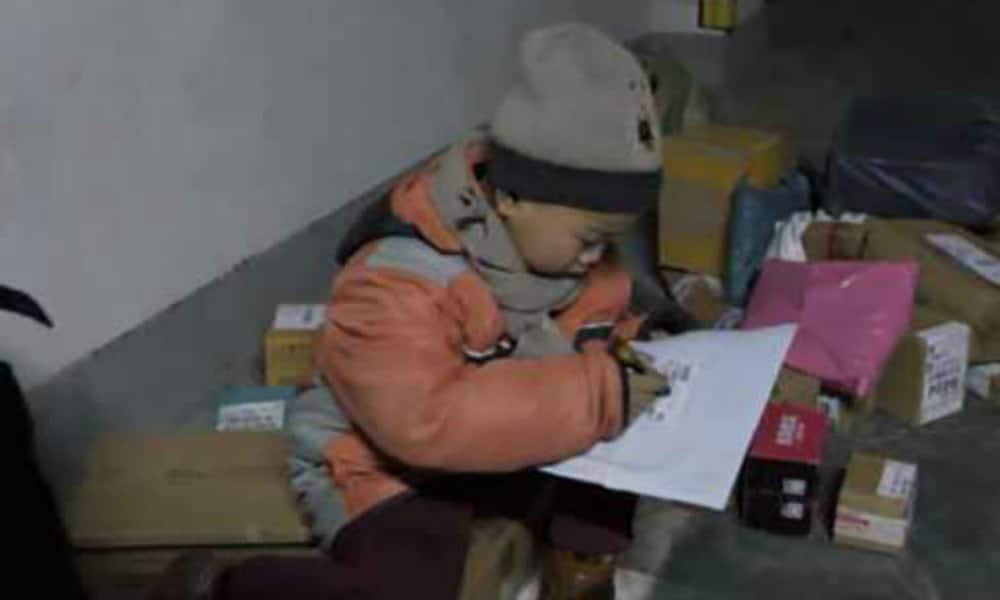

This time it concerns the 7-year-old boy named Chang Jiang (长江) who works as a ‘kuaidi’ (快递) express delivery boy in a district of Qingdao city.

Chinese media outlet Pear Video (@梨视频) reports that the boy’s father has passed away due to illness and that his mother has been remarried, and has since been out of touch with her son.

The boy is now living with his father’s former colleague, his “uncle,” whom he started helping in his daily work as a kuaidi. After a while, Chang Jiang got so experienced in delivering packages that he is now doing the work by himself.

The boy is delivering around 30 packages a day in Qingdao’s Shibei district and has become somewhat of a local celebrity. Chang Jiang told reporters that he was happy doing his job and still wants to be a delivery man when he grows up.

Since a video on Chang Jiang’s story has gained wide attention in the Chinese media, local authorities stated that they would look into how to get Chang Jiang to go to school, and that they are helping the boy to get back in touch with his mother. The boy has a rural ‘hukou’ (household registration) and has no access to public education in Qingdao.

“First the ice boy, now the kuaidi boy,” a typical comment on Weibo said: “How many of these children are out there?”

Although a nine-year education is compulsory in China, children with a rural hukou (registration) have restricted access to public schools and social services in urban areas; this means that many children of migrant workers in the cities receive no formal education.

It also is one of the reasons why some parents leave their children behind in their hometowns to be looked after by grandparents or elder siblings when they go out to work in urban areas.

According to the latest reports, Chang’s mother has not been found yet. One school in Qingdao, however, has offered to take Chang in as a student.

On Weibo, many people speak out in support for Chang Jiang and his ‘uncle,’; they also condemn the boy’s mother: “The mother does not take any responsibility – what a poor kid! I just hope a bright future awaits him.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China World

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

How Chinese social media is making sense of the first geopolitical shockwaves of 2026.

Published

2 days agoon

January 8, 2026

2026 hasn’t exactly seen a peaceful start. In a shocking turn of geopolitical events, Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro was captured by the US on Saturday. Facing narco-terrorism charges, he was flown to New York, where he is still being held in custody alongside his wife, Cilia Flores. President Trump announced that the United States would be taking control in Venezuela, stating they are going to “get the oil flowing.”

Maduro has pleaded not guilty to the charges during an initial hearing in federal court. Meanwhile, Maduro ally Delcy Rodríguez was formally sworn in as Venezuela’s interim president, while up to 50 million barrels of oil resources are set to go to the US.

Further shaking up geopolitical tensions were Donald Trump’s comments suggesting an American takeover of Greenland, arguing that the US needs to control Greenland to ensure the security of the NATO territory in the face of rising threats from China and Russia in the Arctic.

On Chinese social media, these developments have been dominating trending lists, with “Greenland” (格陵兰岛), “military force” (武力), “Trump” (特朗普), “Venezuela” (委内瑞拉), and “Maduro” (马杜罗) among the hottest keywords across various platforms from January 6 to today.

So what is the main gist of these discussions? From official reactions to dominant interpretive frames used by Chinese commentators and bloggers, there are various angles that are highlighted the most. I’ll explore them here.

🔴 China’s Official Response: Stressing Sovereignty & Strategic Ties

Chinese officials strongly condemned the capture of the Venezuelan president. Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) stated in Beijing on Sunday that China has never accepted the idea that any country has the right to act as an “international police” or an “international judge.” The Ministry of Foreign Affairs called for Maduro’s immediate release.

Spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) described the strikes on Venezuela as “a grave violation of international law and the basic norms governing international relations,” while spokesperson Mao Ning (毛宁) condemned what she called the United States’ “long-standing and illegal sanctions” on Venezuela’s oil sector.

These statements match the broader trajectory of China–Venezuela relations.

Over the past decades, particularly since Xi Jinping’s leadership began, the relationship between the two countries has evolved from a basic economic partnership into a more strategically significant one.

During Maduro’s 2023 visit to Beijing, the two sides elevated China–Venezuela ties to a so-called “all-weather strategic partnership” (全天候战略伙伴关系), signaling close, deep, and broad bilateral relations that go beyond a general partnership, with oil cooperation as a central pillar. (In 2025 alone, Venezuela exported around 470,000 barrels per day of crude oil to China.)

Following China’s condemnation of the US actions, Venezuelan Foreign Minister Gil expressed gratitude for China’s support, underscoring their bilateral friendship.

Beyond the official response to the recent developments, there are three main frameworks within which the ‘Trump turmoil’ is discussed on Chinese social media.

🔴 Three Main Angles in China’s Online Debate

🔷 1. Major Power Politics & US Aggression

Chinese media commentators are calling Trump’s capture of Maduro a potential “major turning point” for the world. While many described the developments as a sign that “the world has gone crazy” (这个世界太疯狂了), those trying to make sense of what happened see the US move as a warning: that relatively weak countries may increasingly become playgrounds for major powers & potential targets of US aggression.

Within this reading, China is portrayed as the most stable and peaceful superpower, increasingly important in a future multipolar world order.

On the popular podcast Qiánliáng Hútòng FM (钱粮胡同), recent developments were discussed as part of America’s dominant behavior on the world stage over decades. The hosts argued that, unlike previous US leaders, Trump is far less secretive about his goals and, in this case, no longer even follows the process of seeking UN authorization or congressional approval.

Similar views appeared elsewhere, including in a trending Bilibili video by the political commentary channel Looking at America from the Inside (内部看美国), which described the Venezuela raid not as an endpoint, but as a “signal” of what is yet to come, as the US, sensing structural decline, increasingly acts reactively rather than strategically.

Zhihu author Fēng Lěng Mù Shī (枫冷慕诗), whose post rose in the platform’s popularity charts on Wednesday, also framed the moment as pivotal. While the US may once have held the upper hand, they argue, other countries now have an actual choice in which side to take in a world ruled by superpowers. They write:

💬 “If the US truly had the strength to crush everyone and dominate everything completely, it might still be able to control global affairs. But now, with the rise of China, countries bullied by the US have new choices. If you were one of them, what would you choose? To cooperate with a bandit who might kill you with an axe at any moment? Or to cooperate with a reasonable businessman who follows the rules? I believe any rational person would make the obvious choice.“1

Social media posts made with AI featuring “Know-It-All Trump” or “The King of Understanding.”

At the same time, US behavior also became a source of banter. Some netizens, from Bilibili to Xiaohongshu, posted about “The Know-It-All King” (懂王 Dǒng Wáng—a Chinese nickname for Trump reflecting his often-quoted claims to understand complex issues better than anyone) as a comical villain on a shopping spree for new territories to conquer.

Weibo post: a creative solution to the Greenland issue?

One poster offered a creative solution to the Greenland issue:

💬 “Regarding Greenland, a simple diplomatic solution would be for Barron Trump [Trump’s son, b. 2006] to marry Princess Isabella [of Denmark, b. 2007], with Greenland given to the United States as the dowry. 😁”

🔷 2. The Taiwan Parallel

Taiwan also quickly entered the discussion. In English-language media, some commentators suggested that the raid on Venezuela could smooth and accelerate Beijing’s path toward taking Taiwan.

China’s Taiwan Affairs Office firmly rejected such comparisons. Spokesperson Chen Binhua (陈斌华) emphasized that the Taiwan issue is China’s internal affair and fundamentally different from Venezuela’s situation. Many social media commenters also argued that comparing Venezuela to Taiwan makes little sense, stressing that Venezuela is a sovereign state while Taiwan is considered a province of China.

Even so, Taiwan continues to surface in discussions on Venezuela in various ways. Some users jokingly suggested that the US has now provided a “copy-paste example” of what a tactically impressive raid might look like, while others more seriously draw comparisons between the arrest of Maduro and a hypothetical arrest of Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te.

The central question in these debates, also raised by Taiwanese media commentator Hou Han-ting (侯汉廷), is this: if Lai Ching-te were captured alive in Beijing today, what right would the United States have to object? A common view in these discussions is that Trump’s actions lower the threshold for such scenarios and implicitly pave the way for China’s ‘reunification’ with Taiwan.

This reading seems to sharply contrast Washington’s own framing. In a speech on Monday, US Defense Secretary Hegseth described China as the US’s primary competitor and claimed that America is “reestablishing deterrence that’s so absolute and so unquestioned that our enemies will not dare to test us.”

On Chinese social media, however, this claim is openly questioned: does the raid on Venezuela actually deter China or Russia, or does it instead give them greater freedom of action?

💬 As political commentator Hu Xijin wrote on Weibo: “Americans might do well to ask the Taiwan authorities, and look at the global media commentaries, if the US military action in Venezuela has made the Democratic Progressive Party authorities pushing Taiwan independence feel more secure, or more anxious?”2

🔷 3. Little Europe and the Big Striped Wolf

A third major angle centers on Europe’s role. Hu Xijin has been particularly active in commenting on these developments, especially after Tuesday’s joint statement by the leaders of seven European countries pushing back against Trump’s Greenland remarks.

Hu described the moment as one of “unprecedented turmoil within the Western bloc” and, with Denmark (including Greenland) being a NATO member, as a signal of “the collapse of the so-called ‘values alliance’.”3 This idea was further strengthened by Trump’s withdrawal from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, alongside exits from 65 other organizations, which he described as “contrary to the interests of the United States.”

On Chinese social media, Europe is, on the one hand, seen as one of the weakest actors in this geopolitical episode, while at the same time being criticized as the biggest “hypocrite.”

This week’s joint statement—and Europe’s broader position—are framed as weak due to Europe’s structural dependence on the US.

Weibo commentator Zhang Jun (@买家张俊) argues that Europe leans on a “rules-based international order” which, in reality, would amount to little more than a “US-based order” should Trump succeed in taking Greenland. At the same time, the European statement lacked economic sanctions or concrete follow-up measures, amounting to little more than mere rhetoric.

💬 As one nationalistic account put it: “Europe wonders why, even after kneeling down and licking America’s shoes, it still ends up getting hit.”4

Europe is mainly criticized for being “hypocritical” for remaining largely silent on Venezuela, while forcefully defending Greenland’s sovereignty once Trump turned his attention there.

Britain, in particular, has been singled out in Chinese media narratives surrounding the developments in Venezuela. Guancha ran a piece accusing the BBC of instructing journalists not to use the word “kidnap” when describing Maduro’s capture, suggesting the broadcaster was “whitewashing” the US’s illegal actions. It also pointed to Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s response in a BBC interview, describing his comments on US actions against Venezuela as “playing tai chi” (打起了太极)—a Chinese idiom for being evasive and dodging the question.

One Weibo user (@突破那一天) noted that a Jan 5 speech by Foreign Secretary Cooper appeared to frame US actions as contextually justified, while simultaneously stressing that Greenland’s future is a matter solely for Greenlanders and Danes—accusing her of applying a double standard on sovereignty and speaking out clearly only when the target is a Western ally.

Other users summed up Europe’s role as one of “deceiving others and deceiving themselves” (自欺欺人).

Another commenter suggested that Europe has been so focused on perceived threats from Russia and China while throwing itself into America’s arms, that it failed to notice the real danger. “Oh Europe, little piggy Europe,” they mocked. “You’ve let the wolf into the house.”

🔴 “You Think the US Invasion of Venezuela is None of Your Concern?”

How unexpected was the American military operation in Venezuela, really? One final aspect that trended online was how eerily familiar it all felt.

In the second book of the popular 2008 Chinese sci-fi trilogy The Three-Body Problem, author Liu Cixin (刘慈欣) described a scenario in which Venezuela, ruled by the fictional President Manuel Rey Diaz, is attacked by the US. That Venezuela storyline from the sci-fi novel has become widely discussed for its parallels to the current developments.

The Three Body Problem from 2008 featured a storyline about the US invading Venezuela.

The famous Japanese anime series Black Jack (怪医黑杰克) by Osamu Tezuka (1928–89) also went trending for featuring a fictional plot that many netizens see as strikingly similar to what happened in Venezuela.

It involves the president of the United Federation, named Kelly, citing “global justice” to justify cross-border airstrikes on the presidential residence of the small, oil-rich fictional country Republic of Aldiga, before arresting its leader, General Cruz. Some netizens noted how the blond President “Kelly” even somewhat resembles Trump.

Scenes from Black Jack (怪医黑杰克) by Osamu Tezuka

(Some commenters argued that Osamu Tezuka was not predicting the future so much as drawing on an already familiar pattern of US interventions abroad, and that the character “Kelly” was more likely modeled on Ronald Reagan.)

In Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem, there’s a classic line told by retired Beijing teacher Yang Jinwen to former construction worker Zhang Yuanchao, who dismisses world news as “irrelevant”. In the book, Yang tells him:

📖 “Every major national and international issue, every major national policy, and every UN resolution is connected to your life, through both direct and indirect channels. You think the US invasion of Venezuela is none of your concern? I say it has more than a penny’s worth of lasting implications for your pension.”5

In the current situation, some netizens think that the quote needs to be rewritten. In 2026, it would be:

💬“Do you really think the US arresting Venezuela’s president Maduro, conflicts in the Middle East, tensions across the Taiwan Strait, or Europe’s energy crisis are none of your concern? Don’t be naive. They drive up electricity bills, food prices, and mortgage rates. In the end, what gets drained is both your wallet and your future retirement security.”

It’s clear that many people are, in fact, deeply concerned about these geopolitical developments. As some have noted, science fiction is not always about distant futures. Sometimes, it turns out, we are already living in them.

In Liu Cixin’s version of the story, ‘Rey Diaz’ drives the Americans away through a united fight of the people, breaking the streak of victories by major powers over developing countries and turning the Venezuelan president into a hero of his time.

This story, I suspect, is going to end very differently. For now, it is still being written.🔚

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 “如果说美国人有实力碾压一切,彻底的一家独大,那或许他还可以继续操控世界的局势,但如今随着咱们的崛起,全世界被美国欺凌的国家就有了新的选择,假如你是他们,你会做出什么样的决定? 是和一个随时会砍死你的强盗合作?还是和一个讲道理讲规则的生意人合作?我觉得所有的正常人都会做出合理的判断.”

2 “美国人最好问一问台湾当局,也看一看世界媒体的评论:美军在委内瑞拉的行动究竟让推动“台独”的民进党当局更加安心了,还是更加惶恐不安了?”

3 “欧洲7国领导人和丹麦领导人共同发表声明,反对美国吞并格陵兰岛,这标志着西方集团前所未有的内乱以及 它们的所谓”价值同盟”面临崩溃.”

4 “欧洲:我都跪下舔美国鞋子了、你为什么还要打我.”

5 “我告诉你老张,所有的国家和世界大事,国家的每一项重大决策,联合国的每一项决议,都会通过各种直接或间接的渠道和你的生活发生关系。你以为美国入侵委内瑞拉与你没关系?我告诉你,这事儿对你退休金的长远影响可不止半分钱”

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Eye on Digital China/What’s on Weibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Featured

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

From top trends to platform scandals, these were the biggest online topics of the year.

Published

2 weeks agoon

December 30, 2025

Entering 2026, let’s take this time to reflect on a year of social media in China and the most noteworthy trending stories.

This is a list of major controversies & online moments that not only went completely viral but were also intrinsically connected to China’s social media sphere, either because they blew up on Weibo, originated on Douyin, or would not have even come to light if it weren’t for Xiaohongshu or other Chinese apps.

This is my pick of the top 10 topics and discussions that stood out most this year, capturing the broader sentiments shaping China’s social media landscape in 2025.

(PS: The items on this list are numbered chronologically and are not indicative of the importance/weight of the story.)

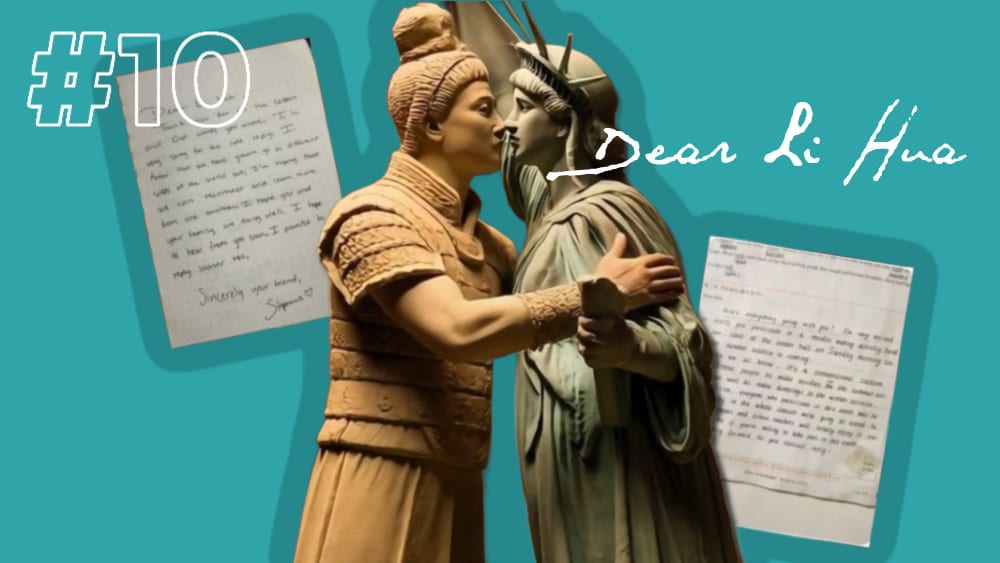

10. The ‘TikTok Refugee’-Xiaohongshu Honeymoon

At the beginning of 2025, a rare moment unfolded on Chinese social media. As American TikTok users faced a looming U.S. ban, they migrated to the Chinese app Xiaohongshu. This massive influx of so-called “TikTok refugees” (TikTok 难民) unexpectedly propelled Xiaohongshu to the number-one spot in app stores across the U.S. and beyond.

While the movement initially began as a tongue-in-cheek protest mocking U.S. authorities’ panic over Chinese companies stealing data, it soon turned into a genuine moment of cultural connection, as international users began building real relationships with the Chinese community on a fully domestic platform—sharing recipes, discussing culture, and practicing language.

Amid geopolitical tensions and a desire for cultural exchange, the fictional character ‘Li Hua’ unexpectedly emerged as a bridge between Chinese and American netizens. Li Hua (李华) is a familiar figure in China’s English writing exams, often used as a ‘stand-in’ for students to write letters to an imaginary foreign friend. Chinese users began digging up old exam papers and sharing the letters they had written years ago, often with captions like “Why didn’t you reply?” as a playful suggestion that Chinese students had been reaching out to foreign friends for years without ever hearing back.

Then, something extraordinary happened: Americans started replying to Li Hua. Posts appeared addressed to the fictional character, with messages like, “Dear Li Hua, I’m sorry the world kept us apart.”

These exchanges came to symbolize the distance that has long separated Chinese and American people. For many, this ‘Xiaohongshu moment’ underscored how anti-Chinese and anti-American sentiments have shaped narratives for years, fostering mutual misunderstanding. At the same time, the moment demonstrated not only the growing reach of Chinese-made platforms, but more importantly the power of online spaces to reshape relationships & create moments of unity amid a widening digital and geopolitical divide.

9. The China Tour of American Livestreamer IShowSpeed

Before March of 2025, many people in China had never heard of American livestreamer IShowSpeed. In the United States, many followers of the online celebrity, whose real name is Darren Jason Watkins Jr, knew little about China. That all changed when the YouTuber, who already had over 34 million followers at the time, toured across China and did a total of eight livestreams, filming over 43 hours of footage from, among others, Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, and Chongqing.

IShowspeed’s China tour was an important media moment for several reasons. In China, where the 20-year-old IShowSpeed is known as Jiǎkànggē (甲亢哥) or ‘Hyperthyroid Bro’ for overdrive being his modus operandi, his tour was seen as a huge win for China’s foreign-facing propaganda and cultural diplomacy. Watkins’ livestreams became an ultimate representation of the Chinese cultural promotion playbook, featuring traditional opera, pandas, Kung-fu, the Great Wall, and traditional medicine alongside futuristic cities, high-speed rail, dancing robots and stunning drone shows.

Outside of China, the streams filled with cultural highlights mixed with cutting-edge technology were also embraced by fans who loved seeing the encounter of a young modern American with old traditional China, and appreciated how his energetic livestreams showed an entirely different side of China than that usually highlighted in American mainstream media. The tour attracted millions of new subscribers, and boosted Watkins’ brand and global fame.

What his visit showed is that China has entered a phase in which it is becoming more skilled at letting others help tell its story in ways that resonate with a young, global, online audience, with more livestreamers and influencers now following in his footsteps through similar trips and China-focused promotions. Even if the government did not pay the YouTuber directly (as his team emphasized), the trip was clearly coordinated and fit seamlessly into China’s broader soft power strategy.

8. The Mysterious Death of Internet Celebrity Cat Wukong

Wukong became one of China’s most beloved internet celebrity cats after Douyin bikepacking vlogger Zhao Shuo (赵朔) met the stray while camping during his journey across China (video). Cold and hungry, the cat meowed outside Zhao’s tent until he let her warm up inside his sleeping bag.

Zhao named her “Wukong,” after the Monkey King from Journey to the West, and took her along on his travels through western China, winning over millions of netizens in the process.

The happy story took a dark turn in April of 2025 in Ruoqiang County, Xinjiang, when Wukong suddenly went missing from the campsite. Using her GPS collar, Zhao found her lifeless body beside a highway just two hours later. Veterinarians found no signs of trauma, ruling out a vehicle collision or accident, while GPS data suggested the cat had been moved unusually far in a short time, raising unanswered questions about what had happened.

As Zhao searched for answers, local authorities became involved. Soon after, Zhao suddenly released a video apologizing for the “negative impact” of the incident and said he would stop pursuing the matter. Online mourning over Wukong quickly turned into backlash, with many netizens accusing local officials of pressuring Zhao into an apology and prioritizing narrative control over transparency.

As the story was muted, tributes to Wukong spread across China in the form of graffiti, artwork, and memorial posts (see here). For many, Wukong became more than an internet cat: her story became a symbol of ordinary citizens searching for truth in the face of official silence. Beyond representing the limits of speaking out online, this story was above all else about the special and moving bond between a man and his cat friend.

7. The Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal of the Year

Many things came together in late April of 2025 when a letter written by the legal wife of the renowned Beijing surgeon Xiao Fei (肖飞) at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital was widely circulated from WeChat to Weibo, Zhihu, and beyond.

In the letter, addressed to the hospital’s Disciplinary Committee, the wife exposed her husband’s serious violations of professional ethics and his extramarital affairs with, among others, a head nurse and the young resident physician Dong Xiying (董袭莹). Most shockingly, she provided evidence that Xiao had left a patient on the operating table for 40 minutes during a surgery due to a dispute involving his mistress.

As the hospital verified the claims, Xiao’s employment was terminated and he was expelled from the Communist Party, briefly becoming one of the most hated figures on the Chinese internet. Public attention then shifted toward Dong Xiying and her suspicious academic rise. Netizens questioned how she managed to transition from an economics degree to becoming a “model student” at the prestigious Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) in just a few years.

The scandal intensified when PUMC, which had previously promoted Dong as a success story, suddenly deleted articles about her and edited her name out of official commencement addresses.

The entire story caused something of an earthquake—not just within medical circles, but also in academic ones and across the internet at large, where netizens were particularly concerned about the broader social issues this story touched on: from fairness in education and corruption in academia to medical negligence and moral integrity.

6. The Labubu Craze & Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Known and loved by tweens, teens, and (female) Gen Z consumers all over the world, Labubu became the hottest toy and fashion accessory of 2025—as well as a breakthrough success for the Chinese designer toy market at large.

Labubu is a Gremlin-like character created by renowned Hong Kong-born artist Kasing Lung (龍家昇), whose work is inspired by Nordic legends of elves. Although Labubu has been around since 2015, it wasn’t until it became part of Chinese pop culture store POP MART’s toy lineup in 2019 that it began reaching a mass audience.

And so, the story of Labubu’s success is just as much the story of the success of POP MART and that of other Chinese companies following a similar journey by covering the entire chain of trendy toys, from product development to retail and marketing. From Labubu to other dolls such as Wakuku and Baby Three (BB3), these brands managed to hit such a cultural and commercial sweet spot over the past year.

Following the global popularity of the Chinese game Black Myth: Wukong and with China’s animation hit Ne Zha 2 hitting cinemas across the world, Labubu is lauded as another example of a successful Chinese cultural export, with experts calling it ‘a benchmark for China’s pop culture’ and viewing its success as a sign of the globalization of Chinese designer toys.

5. The “Nanjing Sister Hong” Case That Shook People’s Worldview

Recently, I was talking to a group of young Chinese students in Wuhan, explaining the kind of trending topics I write about for What’s on Weibo / Eye on Digital China. I mentioned a few examples, and not all stories seemed to ring a bell, but when I said I also covered the “Nanjing Sister Hong” (南京红姐) case, every single one of them had a strong reaction—from squeaks to giggles to burying their faces in their hands. It’s clear that this is a story that not only became one of the most discussed viral topics of the year, but also one that has become part of China’s popular cultural memory, with references to the story popping up everywhere, from online memes to comedy shows and Halloween costumes.

The case centers on the 38-year-old Mr. Jiao, who posed as a woman on different Chinese dating apps. As the red-haired ‘Ahong,’ he hooked up with many men in his rented room, secretly recording these encounters and uploading all of the footage online. The scandal surfaced online in July of 2025.

The exact number of men Jiao met and filmed remains unknown. While authorities have dismissed the viral claim of over 1,600 men as exaggerated, dozens of videos spread widely online, showing Jiao engaging in various forms of sexual activity with different male partners from all walks of life, from married businessmen to fitness trainers and foreign exchange students. Some women who saw the videos recognized their own partners in them.

The story caused significant social shock; the fact that so many (married) men would be willing to hook up with a stranger online who arguably, yet obviously, wasn’t actually female shook people’s worldviews on multiple levels. Although this triggered many jokes, it also raised uncomfortable questions about how many of these men put their wives and romantic partners at risk because of these unprotected encounters.

Chinese commentators and bloggers therefore tied the case to women’s sexual health, but social media discussions around the case also touched on other issues such as privacy violations, gender identity, fluid sexuality, and marginalized communities.

4. The Maskpark Scandal That Couldn’t be Displayed

Back in 2020, an online sex crime scandal known as the “Nth Room” shook South Korea. It made global headlines after news revealed that dozens of women and underage girls had fallen victim to a network of cybersex trafficking and exploitation on Telegram.

In August 2025, the Chinese internet was hit by a similar storm. The discovery of a large-scale, anonymous Chinese-language community on the encrypted Telegram app revealed a vast network of sexual exploitation and voyeuristic content, leading many to label the case China’s own “Nth Room.”

The group, named “Maskpark,” had over 100,000 members and dozens of subchannels sharing voyeuristic footage: girls recorded with hidden cameras in bathrooms; videos leaked through private home surveillance; and women unknowingly filmed in hotels, hospitals, or on the subway. The group even had a specific term for members sharing footage of their own sisters, mothers, wives, or daughters: “offering tributes” (shàng gòng, 上供).

As Maskpark switched to private, frustration grew over the lack of official investigation into the matter. Another major issue fueling the anger was the censorship of “Maskpark Gate.” The story was kept off trending lists, and searching the hashtag on Weibo returned the message: “This topic content cannot be displayed.”

While online sleuths and victims tried to amplify their voices to force action, they instead saw their posts deleted. This left many wondering who is actually standing up for women’s safety, while others pointed out that the scandal reveals how advanced hidden camera technology has become, making this not just a women’s issue, but a national problem.

3. The Jiangyou Incident: From School Bullying to Public Protests

In August 2025, the city of Jiangyou in Sichuan became the scene of a rare, large-scale protest following public outrage over a severe bullying incident and how it was handled.

The bullying incident at the center of this story happened outside school premises, involving three girls between the ages of 13 and 15 who ganged up on a 14-year-old girl named Lai (赖). Footage of the assault, recorded by bystanders, began circulating widely on Chinese social media, sparking widespread outrage among concerned netizens and parents.

When authorities acted not only slowly but also leniently towards the bullies, public anger grew—especially because one of the bullies could be heard saying in the videos, “It’s not like I haven’t been taken in [to jail] before.” The incident sparked anger due to lenient laws for minors, the calculated moves by the brutal bullies, and the epidemic of school violence that has been ongoing in China for years, which many feel is being inadequately handled by local authorities.

The outrage in Jiangyou grew so large that it spilled from online to offline, with crowds gathering outside the municipal building. As the crowd grew, tensions escalated, leading to rare clashes between protesters and police, footage of which spread online before being censored.

The case showed that as the rising number of bullying cases continues to fuel public frustration nationwide, local anger will continue to intensify, especially if authorities fail to address and prevent school bullying. Most of all, it shows that while public protests rarely grow so big on Chinese social media, it only takes a spark to create a heated crowd.

2. The Jingdezhen “Chicken Chop Bro”

Andy Warhol’s famous “15 minutes of fame” phrase, coined around 1967, predicted that modern media & pop culture would eventually make everyone briefly famous. By now, we know there is truth to his words. While social media didn’t make everyone famous, it has proven that anyone could be, if only for a little while.

But Warhol perhaps couldn’t have predicted that the recipe for online fame in China’s 2025 isn’t about money, flashy fashion, or showbiz talent. Instead, it is about being down-to-earth and raw. One of the Chinese hot phrases of the year was “Real-Person Vibes” (huó rén gǎn, 活人感), describing people or stories that feel unpolished and unfiltered—something that has become increasingly precious in a year dominated by AI-generated content.

Around the National Day holiday, a seller of chicken chops in the town of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi became insta-famous. Not just because his chicken chops suited the tastes of locals, but mostly due to his pragmatic attitude and lively energy, along with his superspeed service and clear order of serving customers. He ran his little food stall like a serious operation, and people appreciated that.

Under the nickname “Chicken Chop Brother” (鸡排哥 jīpáigē), Li Junyong (李俊永) became an overnight viral sensation, so successful that local authorities had to implement crowd management for his stall.

While these kinds of successes aren’t always everlasting, their impacts are major. In a time when many are trying to replicate this viral formula, his story shows that for a moment to truly strike a chord with the masses, it needs to be real—and tasty, too.

1. The Kuaishou Livestream Controversy

On the night of December 22, 2025, users scrolling through livestreams on the popular short video app Kuaishou noticed something deeply disturbing: their screens suddenly filled with pornographic and violent content. Soon, millions of users scrolled into the same shocking footage. The chaos continued for approximately 90 minutes before Kuaishou—which has over 415 million daily active users, including many minors—eventually shut down its entire livestreaming function around 11:30 PM.

In a statement the following day, Kuaishou claimed the platform had fallen victim to an attack by “the underground and gray industries,” announcing that the incident had been reported to the police. The event is not just China’s worst platform-level catastrophe of the year; it is one of the most dramatic management failures in Chinese internet history, considering millions witnessed explicit content in real-time for an hour and a half.

The incident is indicative of Kuaishou’s failing security operations, particularly its slow response time and lack of emergency protocols. More significantly, it revealed the advanced techniques of the attackers. They used approximately 17,000 “zombie accounts” acquired through long-term “account farming” to exploit vulnerabilities and bypass reviews. They then pushed pre-recorded explicit files to livestream servers while simultaneously paralyzing Kuaishou’s banning system.

This serves as a massive wake-up call for both Chinese platforms and authorities. In what is already one of the most extensive & sophisticated internet censorship systems in the world, regulatory control and scrutiny will only further intensify in China’s online environment in the year to come.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Eye on Digital China/What’s on Weibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

Why Were 100,000 Pregnant Women’s Blood Samples Smuggled Out of China?

When an Entertainment Scandal Gets Political: How Wong Kar-wai Survived a Nationalist Storm

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment6 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment6 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital12 months ago

China Digital12 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest