China Digital

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

Key takeaways about the ‘Xi Jinping chatbot’, jokingly referred to as ‘Chat Xi PT’ by foreign media outlets.

Published

2 years agoon

This week, various English-language newspapers reported that China is launching its very own Xi Jinping AI chatbot. China’s top internet regulator is reportedly planning to unveil a new chatbot trained on the political philosophy of Xi Jinping. This Large Language Model (LLM) is humorously referred to as ‘Chat Xi PT’ by the Financial Times and in other foreign media reports.

The Times of India website headlined that “China builds AI chatbot trained on Xi Jinping’s thoughts.” News site Asia Financial reported that “China has unveiled a chatbot trained to think like President Xi Jinping.” Various outlets even called it a “ChatGPT chatbot based on Xi Jinping.”

The Financial Times calls the application “China’s latest answer to OpenAI” and notes that “Beijing’s latest attempt to control how artificial intelligence informs Chinese internet users has been rolled out as a chatbot trained on the thoughts of President Xi Jinping.”

Besides the Financial Times article by Ryan McMorrow, media reports were largely based on a piece in the South China Morning Post authored by Sylvie Zhuang, titled “China rolls out large language model AI based on Xi Jinping Thought.”

Zhuang detailed how Xi Jinping’s political philosophy, along with other themes aligned with the official government narrative, form the core content of the chatbot, which is launched at a time when China “tries to use artificial intelligence to drive economic growth while maintaining strict regulatory control over cybersecurity.”

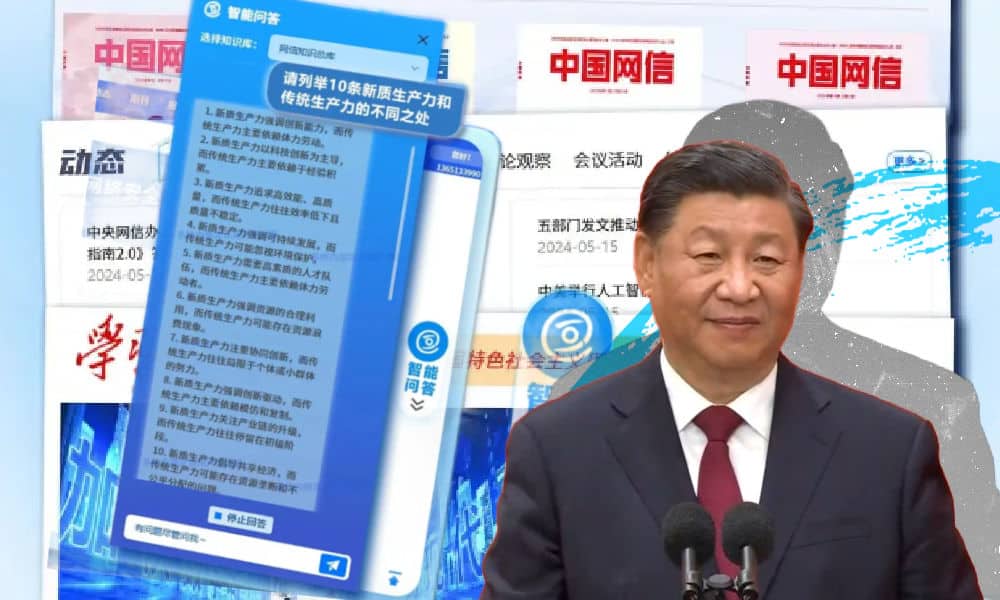

News about the supposed “Xi Jinping chatbot” is based on a post published on the WeChat account of the Cyberspace Administration magazine.

The magazine in question is China Cyberspace (中国网信), overseen by the Cyberspace Administration of China (国家互联网信息办公室) and published by the China Cyberspace Research Institute (中国网络空间研究院).

“Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application”

On May 20, China Cyberspace (中国网信杂志) posted the following text on WeChat, which was viewed less than 6000 times within two days (translation by What’s on Weibo):

“Recently, the Cyberspace Information Research Large [Language] Model Application developed by the China Cyberspace Research Institute has been officially launched and is being tried out internally.” [1]

“As an authoritative and high-end think tank in the Cybersecurity and Informatization field, the China Cyberspace Research Institute relied on the data of the “Internet Information Research Database” and organized a special tech team to independently develop the Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application, to take the lead in demonstrating the innovative development and application of generative AI technology in the field of Cybersecurity and Informatization.”

“The corpus of this Large Model [LLM] is sourced from seven major speciality knowledge bases within the “Internet Information Research Database,” including the “Comprehensive Database of Cyber Information Knowledge”, the “Knowledge Base of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” “Dynamic Cyber Knowledge Base,” “Internet Information Journal Knowledge Base,” “Internet Information Report Knowledge Base,” and more. Users can independently select different categories of knowledge bases for smart question-and-answering. The specialization and authority of the corpus ensures the professionalism of the content that’s generated.”

“Do you want to quickly make a summarized report on the current status of AI development? Are you curious about the differences between ‘new quality productive forces’ and ‘traditional productivity’? This Large Model application can quickly produce it for you!”

“The Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application is based on domestically registered open-source and commercially available pre-trained language models. By combining Information Retrieval technology with specialized Cyberspace Information knowledge, it can do smart question-and-answering [Q&A chatbot], it can generate articles, give summaries, do Chinese-English translations, and many other kinds of tasks in the field of Cybersecurity and Informatization to meet the various demands of users.”

“The system used for the Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application is deployed on a dedicated local server of the China Cyberspace Research Institute. Data is processed from this local server, ensuring high security. This application will become one of the embedded functions of the “Internet Information Research Database” and authorized users invited for targeted testing can access and use it.”

“The Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application will also support users to customize and build new knowledge bases. Users uploading public data and personal documents can analyze and infer, further expanding the scope of personalised use by users.”

Although some Chinese media sources reported on the launch of the application, it barely received traction on Chinese social media.

At the time of writing, the only official accounts posting about the application on Chinese social media are those related to research institutions or the Cyberspace Administration of China.

Key Takeaways on the “Chat Xi PT” Application:

So what are the key takeaways about the so-called, supposed ‘Chat Xi PT’ application that various foreign media have been writing about?

■ Focus on Cyberspace Administration and Digital Governance:

Contrary to some English-language media reports, the application is not primarily centered around Xi Jinping Thought but rather emphasizes Cyberspace Administration and digital governance. Its official name, the “Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application” (网信研究大模型应用), does not even mention Xi Jinping.

■ Not a Rival to OpenAI’s ChatGPT:

Unlike what has been suggested in the media reports, this particular application should not be seen in the light of China “creating rivals to the likes of Open AI’s ChatGPT” (FT). Instead, it caters to a specific group of users engaged in specialized research or operating within certain knowledge fields. There are many others (commercial) chatbots in China that could be seen as Chinese alternatives to OpenAI’s ChatGPT. This is not one of them.

■ Modernization of Cyberspace Authorities:

Rather than solely meeting user demand, the application underscores China’s Cyberspace authorities’ modernization efforts by integrating generative AI technology into their own platforms.

■ Clarifying “Xi Jinping Thought”:

Various English-language media reports conflate “Xi Jinping Thought” with “thoughts of Xi Jinping.” “Xi Jinping Thought” specifically refers to “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” the theories, body of ideas that were incorporated into the Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party in 2017.

■ Nothing “New” about the Application:

The ‘Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application’ is based on existing LLMs and functions as a tool for navigating databases and information in the AI era, rather than representing a groundbreaking innovation or an actual ‘Xi Jinping chatbot.’ While it may have been written as a tongue-in-cheek headline, let’s be clear: there is no such thing as a ‘Chat Xi PT.’

By Manya Koetse

[1]About the translation of the term “网信” (wǎngxìn): in this text, I’ve used different translations for the term “网信” (wǎngxìn) depending on the context of its use. The term can be translated into English as “cyberspace” or “internet information,” but since it is mostly used in relation to China’s Cyberspace Administration and digital governance, it is sometimes more appropriate to refer to it as Cyberspace Security and Information,like the term “国家网信部门” which translates to “national cybersecurity and informatization department” (Also see translations by DigiChina).

🌟 Attention!

For 11 years, What’s on Weibo has remained a 100% independent blog, fueled by my passion to write about China’s digital culture and online trends. Over a year ago, we introduced a soft paywall to ensure the sustainability of this platform. I’m grateful to all our loyal readers who’ve subscribed since 2022. Your support has been invaluable. But we need more subscribers to continue our work. If you appreciate our content and want to support independent China reporting, please consider becoming a subscriber. Your support keeps What’s on Weibo going strong!

Full Text by China Cyberspace:

“近日,由中国网络空间研究院开发的网信研究大模型应用已正式上线并内部试用。

垂直专业:聚焦网信领域

作为网信领域权威高端智库,中国网络空间研究院依托“网信研究数据库”数据,组织专门技术团队,自主开发了网信研究大模型应用,率先示范生成式人工智能技术在网信研究领域的创新发展和落地应用。

该大模型语料库来源于“网信研究数据库”的七大网信专业知识库,包括“网信知识总库”“习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想知识库”“网信动态知识库”“网信期刊知识库”“网信报告知识库”等。用户可自主选择不同类别的知识库进行智能问答。语料库的专业性、权威性保证了生成内容的专业性。

便捷高效:实现多种功能

想快速列出关于人工智能发展现状的报告提纲?想知道新质生产力和传统生产力的不同之处?网信研究大模型应用能够迅速生成!

网信研究大模型应用基于已备案的国内开源可商用预训练语言模型,通过将检索增强生成技术和网信专业知识相结合,实现了网信领域的智能问答、文稿生成、概括总结、中英互译等多种功能,可满足用户的多种需求。

安全可靠:数据本地处理

网信研究大模型应用系统部署在中国网络空间研究院的专属本地服务器,数据由本地服务器进行处理,具有较高的安全性。该大模型应用将成为“网信研究数据库”的嵌入功能之一,获得授权的定点测试用户可以应邀使用该应用。

网信研究大模型应用还将支持用户自定义新建知识库,可通过加载用户自己上传的公开数据、个人文档进行分析推理,进一步拓展用户的个性化使用范围。”

Featured image by What’s on Weibo, image of Xi Jinping under Wikimedia Commons.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Digital

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

From Hong Kong’s Wang Fuk Court fire and China’s new “family member” rule to Japanese concerts halted, the Nantong viral remark, childcare subsidy payouts, 6G trials, and top social media debates.

Published

1 month agoon

December 2, 2025

🔥 China Trend Watch — Week 48–49 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China. This edition was sent to our subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of the China Trend Watch Eye on Digital China newsletter. I have been typing this newsletter from my phone and a tiny tablet on the trains from Chongqing to Wuhan and Wuhan to Nanjing, unfortunately tucked in the middle seat (that place where elbows suddenly become such inconvenient body parts), so please bear with me if spotting any inconsistensies or if the images don’t line up.

Chongqing has been a unique experience — a city in China that has been on my to-visit list for years. Its “cyberpunk” reputation doesn’t really do it justice. There’s this beautiful tension between its old history (century-old stairs, wartime tunnels) and the full speed of the future (neon lights, incredible skyscrapers), with the streets actually smelling like hotpot – such a special mix (or is that, perhaps, just what cyberpunk actually is?!).

Photos by me: View over Chongqing’s Shibati area, and toymachines in a wartime bomb shelter near Libazi.

This time, it was the city’s WWII history that finally pushed me to visit, as I’m on a research trip through several major cities that played important roles in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War — a topic that has become increasingly relevant over the past few months. I’ve already visited some fascinating places, from the former residence of General Stilwell to Chiang Kai-shek’s air-raid shelters and wartime military headquarters. Today I’ll be heading to some war-related museums in Nanjing. More on that later.

I will get back into my normal routine next week when I return from travels.

Let’s dive in.

- 🇨🇳 The 2025 Mnet Asian Music Awards (MAMA), one of the biggest K-pop award shows, sparked online backlash this week after netizens discovered that the event’s voting interface listed Hong Kong and Taiwan as separate countries in its selection menu. Seen as violating the ‘One China’ principle, netizens criticized MAMA for being disrespectful to China (meanwhile, the event was actually held in Hong Kong).

- 💰 As part of a national childcare subsidy plan announced earlier this year (initiated to boost China’s dropping birth rates and support low-income families), parents across the country are now receiving their initial 3,600 yuan ($508) payouts (per child aged 0–3 per year), creating an online buzz and reminding other parents to apply if they haven’t yet.

- 👀 Move over 5G…the 6G era is nearing! China has completed its first real-world testing trial of 6G applications. Being 100x faster than 5G, it’s the future mobile standard. Commercial use is planned for 2030.

- 🎬 Zootopia 2 is everywhere right now and has broken records in China with a US$267 million box office in 5 days. But despite its success there’s also been some backlash over the decision to cast celebrity actors for the main characters in the Chinese version instead of professional voice actors. Fans of the movie felt the performances were subpar, leading fans of the celebrities to defend them.

- 🚹 The 57-year-old Chinese actor and singer Sun Hao (孙浩) made headlines this week, and not for his latest work — but for getting caught urinating in public after a dinner with friends. The incident has triggered discussions about how (un)acceptable it is to pee on the street, and how celebrities should set the right example.

- 🛸 Blending classic Chinese humor with sci-fi elements, the new Chinese urban comedy Sarcastic Family (毒舌舌家) has become an online hit. The comedy is about a mother and daughter from another galaxy who become an unconventional family on planet Earth when the daughter marries a Chinese man, joined in a household by his father and her own outer-space mom.

1. The Hong Kong Wang Fuk Court Fire

The catastrophic residential fire at Hong Kong’s Wang Fuk Court in the city’s Tai Po district (香港大埔) has become the deadliest blaze in Hong Kong in 80 years.

The fire, which broke out on Wednesday at 14:51 local time, spread so quickly that it soon covered a total of seven residential towers. Initially, news came out that the fire had killed at least 13 and injured 28, but the figures soon kept rising. At the time of writing, the official death toll is 151, with 30 people still missing. A total of eleven people have now been arrested in relation to the fire, including two directors of the consultancy firm in charge of the renovation project that was taking place at Wang Fuk Court.

On Chinese social media, the fire has been top-trending news for days. One major point of discussion has been how the fire could have spread so rapidly; what started as a smaller blaze turned into an inferno within minutes. As part of exterior maintenance work, the buildings were covered in bamboo scaffolding and protective netting. Dry weather and strong winds contributed to the rapid spread. Residents said they had repeatedly seen construction workers smoking at the site.

Online conversations initially focused on the bamboo scaffolding, which is traditionally used in construction in Hong Kong for its flexibility and fire resistance. Soon, conversations shifted, blaming the flammable material used in the netting, as well as the styrofoam insulation used to seal windows. Although there are voices speaking out against misinformation regarding the flammability of bamboo, some commenters still point to the bamboo for intensifying the fire and making rescue operations more difficult.

Another issue is the fire system. A former security supervisor alleged the estate’s fire systems were frequently switched off. The claim, reported by local media, has intensified scrutiny and public concern over estate safety management.

What stands out in these discussions on the fire is that people are also tying it to deeper-rooted issues in Hong Kong. Since it’s Hong Kong, there’s arguably some more online room for discussion on such a topic. One Weibo blogger named ‘Jinshu Sister’ wrote: “The blaze exposed two very different worlds within ‘glamorous’ (光鲜) Hong Kong: one world is the fast-moving international metropolis, a playground for capital and elites. The other world consists of citizens living in decades-old buildings. Their hopes of improving their housing have been repeatedly delayed due to practical difficulties, such as costly maintenance fees and the complicated procedures of owners’ corporations. A truly great city is not defined by how many world-class skyscrapers it has, but by whether it can protect the life and safety of every ordinary person living in it.”

2. Living Together Now Counts as “Family Members”

Image by state media outlet CNR: “Living together before marriage is also belongs to [the category of] family members.”

The move is meant to protect victims of domestic abuse and help prosecute abusers within the context of the Anti-Domestic Violence Law. Forms of abuse beyond physical injury (e.g. mental abuse) will also be recognized as domestic violence.

The announcement has sparked heated debates as people began worrying about their current relationships being legally defined as a de facto marriage, with various implications regarding spousal obligations, property rights, and financial issues — including concerns that partners might suddenly be treated as legally responsible for each other’s debts. In recent years, there have been increasing discussions about women marrying to shift their personal debts onto their husbands (there’s even a word for it).

But legal experts on social media say there’s no need to panic: people still need to be legally married to be designated as an official married couple, with all marital obligations and benefits. They emphasize that the current revision is mainly meant to standardize the handling of domestic violence cases nationwide — especially at a time when more young Chinese are delaying marriage and choosing to live together. In the past, there have been cases of men severely abusing their live-in girlfriends, but because they were not legally married, such incidents were treated merely as “ordinary disputes among citizens.”

In light of the many trending stories over the past years concerning domestic violence, you might expect more support for this legal revision. However, people have doubts about how cohabitation will actually be defined in court. One commenter on Weibo wrote: “How should it be defined? If you have sex once a week, is that considered cohabitation? If you stay together for one week every month, is that considered cohabitation? If you have long-term sexual relations but leave after it’s over and don’t sleep together at night, is that cohabitation? There is only one answer: discretionary power (自由裁量权). If the judge says it is cohabitation, then it is cohabitation. Since cohabitation makes you ‘family members,’ can the other party then take half of the house?”

3. Japanese Concerts in China Hit by Sino-Japanese Tensions

Over the past weekend, video footage showing how a concert by Japanese artist Maki Otsuki was suddenly and quite dramatically stopped while she was singing on stage — the lights were turned off, her mic was taken away, and she was escorted off — popped up all over WeChat and beyond (see video on X), followed by various write-ups on the incident, which were soon taken offline.

Ayumi Hamasaki, another famous Japanese artist, also saw her Shanghai concert — 14,000 tickets sold — canceled just a day before the show. Although there was not a single audience member, she performed anyway, leaving her performing alone in an empty venue. She posted about it herself (see photos), expressing sadness over the elaborate stage setup prepared by 200 staff members over several days that now had to be dismantled without the concert ever taking place.

The “lights out” moment for Otsuki, Hamasaki, and many other Japanese artists and musicians in China was attributed to “force majeure” (因不可抗力) in venue statements coming from Beijing, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, and beyond. It comes amid heightened tensions between Japan and China following Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s November 7 remarks suggesting that Chinese actions regarding Taiwan could prompt a military defense response from Tokyo, which infuriated China for “intervening in China’s sovereignty” and has been an ongoing major topic ever since.

On December 1, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian responded to questions about the cancellations during a regular press briefing by saying that reporters should inquire with the Chinese organizers of these events instead — providing no comments on the official reasons behind the wave of abrupt cancellations, which appear to have stemmed from a sweeping directive from Chinese authorities to halt Japanese cultural events.

It’s not only the music and event industry that’s been affected by recent escalations. Chinese airlines have sharply reduced flights to Japan in December, and Japanese movie releases in China have been postponed as well.

There have been mixed reactions following the wave of cancellations. Despite anti-Japanese sentiments online, many people also feel this move unfairly impacts Chinese companies and consumers. Political commentator Hu Xijin addressed the issue, writing: “First, this demonstrates China’s resolve to strengthen sanctions against Japan by cancelling performances by Japanese artists coming to China, and that certainly generates a positive effect. But at the same time, Chinese performance companies will face costs from breaching contracts and from the upfront investments already made; the city of Shanghai and its transportation sector lose a piece of consumption; some audience members who had already traveled from other places to Shanghai are left with nothing; and many ticket holders, especially those who planned to travel from other cities, had their weekend plans disrupted. Taken together, all of these are losses on China’s side.”

Returning to China next week [下周回国] (xià zhōu huíguó)

“Returning to China next week” has been a popular phrase for years in relation to tech entrepreneur Jia Yueting (贾跃亭), who departed China during the 2017 collapse of his LeEco tech company, leaving behind billions in debt.

While going on to found and lead EV startup Faraday Future (FF) in California, Jia repeatedly told Chinese audiences that he would return “next week.” When next week became next month, next year, and eventually never, “returning to China next week” became a running joke on social media, representing big promises with zero follow-up.

Now, Jia has again made headlines after announcing ambitious new plans for the future of FF and autonomous driving. Not only does Jia intend to cooperate with Tesla, he also said that FF and FX (the company’s second brand targeted at the mass market) have a five-year sales target of 500,000 cars. FF’s technology partner AIXC is the newly listed AI x Crypto company that is supposed to shake up the market. Jia’s business strategy has apparently pivoted to trying to create a tech + AI + crypto ecosystem in which each business strengthens the other.

Jia’s latest plans add to the series of grandiose promises that have made him a recurring character in Chinese online discussions. Although often mocked, there is also fascination in how Jia continues to stay in the headlines and attract new investments, seemingly without end.

Of course, after all this, netizens still wonder: “But will he still return to China next week?”

A screenshot showing a cheeky comment from an unexpected account has gone mega viral this week. The comment was made on Douyin by an official local government account in relation to a new law on sealing minor-offence records.

The revised section of the Public Security Administration Law, taking effect on January 1, 2026, adds the possibility of sealing certain administrative violations. Online, people mostly connected this to drug-related offences, wondering whether it would allow people whose names are tied to drug-related penalties to now have their records sealed.

Under a social media post about this issue, the official account of Nantong’s Culture & Tourism Bureau replied: “Which young master was caught using [drugs]?”(“哪位少爷吸了”), jokingly suggesting that the law has been introduced to protect certain individuals from powerful families.

The edgy remark sent the Nantong Tourism Bureau account’s followers up by nearly 1.5 million overnight, eventually adding a total of around 4 million new fans. And although the comment was soon deleted, it has boosted the visibility of Nantong, with some supporters suggesting that if its cultural bureau dares to make such bold remarks, the city itself might be worth a visit.

The moment shows that it only takes a tiny comment to go viral, and that, perhaps, Nantong now has a job opening for a new social media manager to entertain their millions of new followers with content that’s a bit less edgy.😅

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China China Trend Watch. For slower-moving trends and deeper structural analysis, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

If you happen to be reading this without a paid subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

Household notice: if you are receiving duplicate issues of this newsletter in your inbox, you are probably subscribed on both the main site and the Substack platform. For your own convenience, you can unsubscribe from one of them (let me know if you need help with that).

Many thanks and credits to Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang for helping curate the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or

email me. First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform resurfaces in Africa, a new winter hotspot, why Chinese elites ‘run’ to Tokyo, and more.

Published

2 months agoon

November 21, 2025

🌊 Signals — Week 47 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China, Signals highlights slower trends and online currents behind the daily scroll. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Different from the China Trend Watch (check the latest one here if you missed it), this edition, part of the new Signals series, is about the slower side of China’s social media: the recurring themes and underlying shifts that signal broader trends beyond the quick daily headlines. Together with the deeper dives, the three combined aim to give you clear updates and a fuller overview of what’s happening in China’s online conversations & digital spaces.

For the coming two weeks, I’ll be traveling from Beijing to Chongqing and beyond (more on that soon) so please bear with me if my posting frequency dips a little. I’ll be sure to pick it up again soon and will do my best to keep you updated along the way. In the meantime, if you know of a must-try hotpot in Chongqing, please do let me know.

In this newsletter: Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform in Angola, a new winter hotspot, discussions on what happens to your Wechat after you die, why Chinese elites rùn to Tokyo, and more. Let’s dive in.

- 💰 The richest woman in China, according to the latest list by Hurun Research Institute, is the “queen of pharmaceuticals” Zhong Huijuan (钟慧娟) who has accumulated 141 billion yuan (over 19 billion USD). Women account for over 22% of Chinese billionaires (those with more than 5 billion RMB), underscoring China’s globally leading position in producing wealthy female entrepreneurs.

- 🧩 What happens to your WeChat after you die? A user who registered for NetEase Music with a newly reassigned phone number unexpectedly gained access to the late singer Coco Lee’s (李玟) account, as the number had originally belonged to her. The incident has reignited debate over how digital accounts should be handled after death, prompting platforms like NetEase and Tencent to reconsider policies on long-inactive accounts and take stronger measures to protect them.

- 📱 Although millions of viewers swoon over micro-dramas with fantasy storylines where rich, powerful men win over the “girl next door” through money and status, Chinese regulators are now stepping in to curb exaggerated plots featuring the so-called “dominant CEO” (霸道总裁) archetype, signaling stricter oversight for the booming short drama market.

- ☕ A popular Beijing coffee chain calling itself “People’s Cafe” (人民咖啡馆), with its style and logo evoking nationalist visual nostalgia, has changed its name after facing criticism for building its brand – including pricey coffee and merchandise – on Mao era and state-media political connotations. The cafe is now ‘Yachao People’s Cafe’ (要潮人民咖啡馆).

- 👀 Parents were recently shocked to see erotic ads appear on the Chinese nursery rhymes and children’s learning app BabyBus (宝宝巴士), which is meant for kids ages 0–8. BabyBus has since apologized, but the incident has sparked discussions about how to keep children safe from such content.

- 🧧The 2026 holiday schedule has continued to be a big topic of conversation as it includes a 9-day long Spring Festival break (from February 15 to February 23), making it the longest Lunar New Year holiday on record. The move not only gives people more time for family reunions, but also gives a huge boost to the domestic travel industry.

Hasan Piker’s Chinese Tour & The US–China Content Honeymoon

Livestreamer Hasan Piker during his visit to Tiananmen Square flag-rising ceremony.

It’s not time for the end-of-year overviews just yet – but I’ll already say that 2025 was the US–China ‘honeymoon’ year for content creation. It’s when China became “cool,” appealing, and eye-grabbing for young Western social media users, particularly Americans. The recent China trip of the prominent American online streamer Hasan Piker fits into that context.

This left-wing political commentator also known as ‘HasanAbi’ (3 million followers on Twitch, recently profiled by the New York Times) arrived in China for a two-week trip on November 11.

Piker screenshot from the interview with CGTN, published on CGTN.

His visit has been controversial on English-language social media, especially because Piker, known for his criticism of America (which he calls imperialist), has been overly praising China: calling himself “full Chinese,” waving the Chinese flag, joining state media outlet CGTN for an interview on China and the US, and gloating over a first-edition copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao (the Little Red Book). He portrays China as heavily misrepresented in the West and as a country the United States should learn from.

Hasan Piker did an interview with CGTN, posing with Li Jingjing 李菁菁.

During his livestreaming tour, Hasan, who is nicknamed “lemonbro” (柠檬哥) by Chinese netizens, also joined Chinese platforms Bilibili and Xiaohongshu.

But despite all the talk about Piker in the American online media sphere, online conversations, clicks, and views within China are underwhelming. As of now, he has around 24,000 followers on Bilibili, and he’s barely a topic of conversation on mainstream feeds.

Piker’s visit stands in stark contrast to that of American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins), who toured China in March. With lengthy livestreams from Beijing to Chongqing, his popularity exploded in China, where he came to be seen by many as a representative of cultural diplomacy.

IShowspeed in China, March 2025.

IShowSpeed’s success followed another peak moment in online US–China cultural exchange. In January 2025, waves of foreign TikTok users and popular creators migrated to the Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu amid the looming TikTok ban.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against Trump and US policies. In a playful act of political defiance, they downloaded Xiaohongshu to show they weren’t scared of government warnings about Chinese data collection. (For clarity: while TikTok is a made-in-China app, it is not accessible inside mainland China, where Douyin is the domestic version run by the same parent company).

The influx of foreigners — who were quickly nicknamed “TikTok refugees” — soon turned into a moment of cultural celebration. As American creators introduced themselves, Chinese users welcomed them warmly, eager to practice English and teach newcomers how to navigate the app. Discussions about language, culture, and societal differences flourished. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor. It was a rare moment of social media doing what we hope it can do: connect people, build bridges, and replace prejudice with curiosity.

Some of that same enthusiasm was also visible during IShowSpeed’s China tour. Despite the tour inevitably getting entangled with political and commercial interests, much of it was simply about an American boy swept up in the high energy of China’s vibrant cities and everything they offer.

Different from IShowSpeed, who is known for his meme-worthy online presence, Piker is primarily known for his radical political views. His China enthusiasm feels driven less by cultural curiosity and more by his critique of America.

Because of his stances — such as describing the US as a police state — it’s easy for Western critics to accuse him of hypocrisy in praising China, especially after a brief run-in with security police while livestreaming at Tiananmen Square.

Seen in broader context, Piker’s China trip reflects a shift in how China is used in American online discourse.

Before, it was Chinese ‘public intellectuals’ (公知) who praised the US as a ‘lighthouse country’ (灯塔国), a beacon of democracy, to indirectly critique China and promote a Western modernization model. Later, Chinese online influencers showcased their lives abroad to emphasize how much ‘brighter the moon’ was outside China.

In the post-Covid years, the current reversed: Western content creators, from TikTok influencers to political commentators, increasingly use China to make arguments that are fundamentally about America.

Between these cycles, authentic cultural curiosity gets pushed to the sidelines. The TikTok-refugee moment in early January may have been the closest we’ve come in years: a brief window where Chinese and American users met each other with curiosity, camaraderie, and creativity.

Hasan’s tour, in contrast, reflects a newer phase, one where China is increasingly used as a stage for Western political identity rather than a complex and diverse country to understand on its own terms. I think the honeymoon phase is over.

“Liu Sihan, Your School Uniform Ended Up in Angola”: China’s Second-Hand Clothing in Africa

A Chinese school uniform went viral after a Chinese social media user spotted it in Angola.

“Liu Sihan, your schooluniform is hot in Africa” (刘思涵你的校服在非洲火了) is a sentence that unexpectedly trended after a Chinese blogger named Xiao Le (小乐) shared a video of a schoolkid in Angola wearing a Chinese second-hand uniform from Qingdao Xushuilu Primary School, that had the nametag Liu Sihan on it.

The topic sparked discussions about what actually happens to clothing after it’s donated, and many people were surprised to learn how widely Chinese discarded clothing circulates in parts of Africa.

Liu Sihan’s mother, whose daughter is now a 9th grader in Qingdao, had previously donated the uniform to a community clothing donation box (社区旧衣回收箱) after Liu outgrew it. She intended it to help someone in need, never imagining it to travel all the way to Africa.

In light of this story, one netizen shared a video showing a local African market selling all kinds of Chinese school items, including backpacks, and people wearing clothing once belonging to workers for Chinese delivery platforms. “In Africa, you can see school uniforms from all parts of China, and even Meituan and Eleme outfits,” one blogger wrote.

When it comes to second-hand clothing trade, we know much more about Europe–Africa and US–Africa flows than about Chinese exports, and it seems there haven’t been many studies on this specific topic yet. Still, alongside China’s rapid economic transformations, the rise of fast fashion, and the fact that China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of textiles, the country now has an enormous abundance of second-hand clothing.

According to a 2023 study by Wu et al. (link), China still has a long way to go in sustainable clothing disposal. Around 40% of Chinese consumers either keep unwanted clothes at home or throw them away.

But there may be a shift underway. Donation options are expanding quickly, from government bins to brand programs, and from second-hand stores to online platforms that offer at-home pickup.

Chinese social media users posting images of school/work uniforms from China worn by Africans.

As awareness grows around the benefits of donating clothing (reducing waste, supporting sustainability, and the emotional satisfaction of giving), donation rates may rise significantly. The story of Liu Sihan’s uniform, which many found amusing, might even encourage more people to donate. And if that happens, scenes of African children (and adults) wearing Chinese-donated clothes may become much more common than they now are.

Laojunshan: New Hotspot in Cold Winter

Images from Xiaohongshu, 背包里的星子, 旅行定制师小漾

Go to Zibo for BBQ, go to Tianshui for malatang, go to Harbin for the Ice Festival, cycle to Kaifeng for soup dumplings, or head to Dunhuang to ride a camel — over recent years, a number of Chinese domestic destinations have turned into viral hotspots, boosted by online marketing initiatives and Xiaohongshu influencers.

This year, Laojunshan is among the places climbing the trending lists as a must-visit spot for its spectacular snow-covered landscapes that remind many of classical Chinese paintings. Laojunshan (老君山), a scenic mountain in Henan Province, is attracting more domestic tourists for winter excursions.

Xiaohongshu is filled with travel tips: how to get there from Luoyang station (by bus), and the best times of day to catch the snow in perfect light (7–9 AM or around 6–6:30 PM).

With Laojunshan, we see a familiar pattern: local tourism bureaus, state media, and influencers collectively driving new waves of visitors to the area, bringing crucial revenue to local industries during what would otherwise be slower winter months.

WeChat New Features & Hong Kong Police on Douyin

🟦 WeChat has been gradually rolling out a new feature that allows users to recall a batch of messages all at once, which saves you the frantic effort of deleting each message individually after realizing you sent them to the wrong group (or just regret a late-night rant). Many users are welcoming the update, along with another feature that lets you delete a contact without wiping the entire chat history. This is useful for anyone who wants to preserve evidence of what happened before cutting ties.

🟦The Hong Kong Police Force recently celebrated its two-year anniversary on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), having accumulated nearly 5 million followers during that time. To mark the occasion, they invited actor Simon Yam to record a commemorative video for their channel (@香港警察). The presence of the Hong Kong Police on the Chinese app — and the approachable, meme-friendly way they’ve chosen to engage with younger mainland audiences — is yet another signal of Hong Kong institutions’ strategic alignment with mainland China’s digital infrastructure, a shift that has been gradually taking place. The anniversary video proved popular on Douyin, attracting thousands of likes and comments.

Why Chinese Elite Rùn to Japan (by ChinaTalk)

Over the past week, Japan has been trending every single day on Chinese social media in light of escalating bilateral tensions after Japanese PM Takaichi made remarks about Taiwan that China views as a direct military threat. The diplomatic freeze is triggering all kinds of trends, from rising anti-Japanese sentiment online and a ban on Japanese seafood imports to Chinese authorities warning citizens not to travel to Japan.

You’d think Chinese people would want to be anywhere but Japan right now — but the reality is far more nuanced.

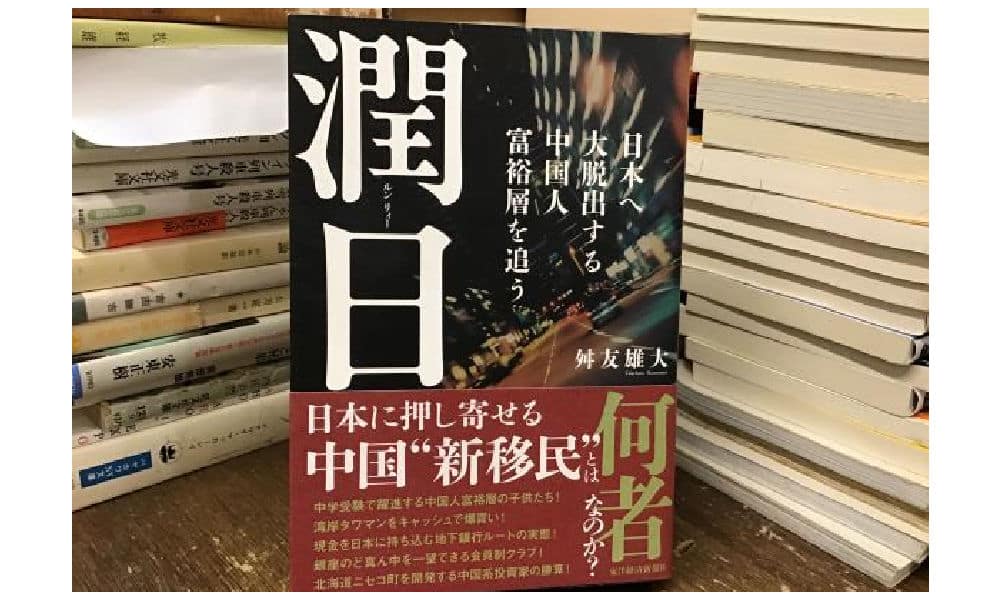

In a recent feature in ChinaTalk, Jordan Schneider interviewed Japanese journalist & researcher Takehiro Masutomo (舛友雄大) who has just published a book about Japan’s new Chinese diaspora, explaining what draws Chinese dissidents, intellectuals, billionaires, and middle-class families to Tokyo.

The book is titled Run Ri: 潤日 Following the Footsteps of Elite Chinese Escaping to Japan (only available in Japanese and Traditional Chinese for now). (The word Rùn 润/潤, by the way, is Chinese online slang and meme expresses the desire to escape the country.)

A very interesting read on how Chinese communities are settling in Japan, a place they see as freer than Hong Kong and safer than the U.S., and one they’re surprisingly optimistic about — even more so than the Japanese themselves.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China Signals. For fast-moving trends and deeper dives, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you just so happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

A small housekeeping note:

This Eye on Digital China newsletter is co-published for subscribers on both Substack and the main site. If you’re registered on both platforms, you’ll receive duplicate emails — so if that bothers you, please pick your preferred platform and unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

Why Were 100,000 Pregnant Women’s Blood Samples Smuggled Out of China?

When an Entertainment Scandal Gets Political: How Wong Kar-wai Survived a Nationalist Storm

China Trend Watch: Quiet Nationalism, Loud Statements, and Nanjing Memorial Day

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment6 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment6 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital12 months ago

China Digital12 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest