China Celebs

Controversy over Chinese Singer Sun Nan Sending His Kids to an Unqualified “Traditional Culture School”

The parents might think it’s a good idea, but what about the children’s future?

Published

7 years agoon

Famous Chinese singer Sun Nan and his wife Pan Wei have left their Beijing life behind and have moved to Xuzhou to send their children to a school that focuses on ‘traditional Chinese culture.’ The decision has triggered controversy online, where many netizens think that acquiring academic skills is more important for children than attending ‘women’s virtue’ classes.

When news came out that famous Chinese singer Sun Nan (孙楠) is sending his children to the Chung Hwa College of Traditional Culture that, among others, has “women’s virtues” in its curriculum, controversy erupted on Chinese social media this week. The hashtag “Sun Nan Sends His Kids to Unqualified School” (#孙楠孩子就读学校无办学资格#) has received more than 260 million views on Weibo at time of writing.

The controversy started over an interview with Sun Nan’s wife Pan Wei (潘蔚), who is currently promoting her new book The Art of Artless Life (素心映照).

In the interview with short video platform Yi Tiao (一条), Pan says that the family had decided to move from Beijing to Xuzhou some three years ago, living in a modest 700-yuan-per month (±$100) apartment in order to send their children to a local “traditional culture” school that was allegedly established 28 years ago.

In the interview, Pan stresses the importance of teaching children traditional Chinese cultural values such as filial piety, as she also specifically mentions the value of teaching girls about being “gentle and kind (through needles and threads)” for when they grow up to be wives and mothers.

The interview soon became a big topic of discussion online, where the school in question was identified as the ‘Chung Hwa College of Traditional Culture‘ (华夏学宫) in Xuzhou, that is focused on teaching traditional Chinese culture to its students and has an annual fee for its junior programme of 100,000 yuan (±$15,000). As also featured in the interview, Pan Wei herself teaches needlework at the school.

The heated discussions on Chinese social media focused on the doubted academic qualification of the school and its teachers, as well as on the intentions of Pan and her husband to send the children to such an institute.

On January 23rd, various media reports disclosed that, according to the Education Department of Xuzhou, the Chung Hwa College of Traditional Culture indeed is not qualified as an official educational institution, and that graduates from this institution also cannot obtain verified certificates, nor participate in China’s National College Entrance Exams.

The courses that are taught at the school have specifically attracted the attention of online commenters. Besides needlework, which is only taught to girls, the school offers so-called “women’s virtue” classes and uses Di Zi Gui (弟子规, Standards for being a Good Pupil and Child) as its main textbook, which was written in the Qing dynasty and is arguably based on the teachings of Confucius.

It is not the first time Chinese “women’s virtue” classes receive criticism online for reinforcing gender sterotypes. In 2018, one “female virtue class” was ordered to shut down after it made headlines.

Sun Nan and Pan Wei got married in 2009 after they had both been married before. From their earlier marriages, Sun had one daughter and a son, and Pan had one daughter, who previously studied at an international school. In 2011, the couple had one daughter together.

Singer Sun Nan has been well-known for his Mando-pop songs for years. He released his first album in 1990 and has had a long-lasting career ever since, receiving various awards for his work as a musician. (You might also remember his performance at the 2016 CCTV Spring Gala, where he performed together with 540 dancing robots.)

On Weibo, many netizens express their idea of Pan Wei as an “evil stepmother” who would allegedly send her own biological daughter to a good school, while purposely enrolling her stepchildren into a school that lacks proper credentials. It even led to some Weibo users leaving comments on the social media account of Sun Nan’s ex-wife, Mai Hongmei (买红妹), asking her to “save” her children from their current predicament.

“Aren’t these children supposed to receive compulsory education?” some wonder, while others worry that the children have been victimized by an “evil cult.” Some even say it is “ruthless” to withhold children from a qualified education, potentially leaving them no chance to enroll in college later on in life.

There are also commenters and bloggers who note that Sun and Pan’s personal involvement in the school, and the reason for sending their children there, is driven by financial interests, suggesting that the couple might be eager to make money by jumping on the “traditional culture” trend.

The head of the Chung Hwa College of Traditional Culture has since denied that the couple owns any shares in the institute. The school’s home page, at time of writing, however, does actively promote Pan Wei’s latest book.

“This controversial issue actually has three sides to it,” one popular Weibo blogger explains, suggesting that (1) the fact that Pan’s own child is enrolled in a qualified school and her step-children are not, makes her look like a bad stepmother with ulterior motives; (2) it is up for debate to what extent parents can choose to send their children to special schools, withholding them from the basic academic education they will need later on in life; (3) it is questionable to what extent it is good for young children to learn about ‘women’s virtues’ and obedience, and one might wonder what motives lie behind sending one’s children to such a school.

For now, the Xuzhou Education Department has stated that they will further investigate the matter. According to Chinese law, children must attend primary and junior secondary school for at least nine years in total. Meanwhile, Sun Nan has not responded to the controversy on his official Weibo page yet.

Watch the video of the controversial interview with Pan (with English subtitles) here:

By Boyu Xiao and Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Boyu Xiao is an MPhil graduate in Asian Studies (Leiden University/Peking University) focused on modern China. She has a strong interest in feminist issues and specializes in the construction of memory in contemporary China.

China Celebs

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Published

4 months agoon

June 27, 2025

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China this week. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Chinese beauty influencer and livestreamer Du Meizhu (都美竹) is facing online backlash this week after a former female fan filed a police report accusing her of scamming her out of nearly 200,000 yuan (approx. US$27,800).

The fan, known online as Sister Bing (Weibo handle @冰点人a冰点), has come forward with detailed allegations, claiming Du began swindling her in 2022.

Du Meizhu rose to national prominence in 2021 when she was 19 years old and became the first person to publicly accuse Chinese-Canadian pop star Kris Wu (吴亦凡) of rape and sexual misconduct. After at least 24 more victims also came forward, Wu was formally arrested on suspicion of rape in mid-August 2021 and was later sentenced to 13 years in prison.

It was around this time that ‘Sister Bing,’ whose real name is Ms. Zhu (朱, born 1979), started following Du Meizhu on social media. As a hard-working single mother of a daughter, she said she sympathized with Du and wanted to show her some support. In a Weibo post published in 2024, she detailed how Du Meizhu began noticing Zhu’s online interactions in early 2022 and added her as a friend on WeChat.

In private conversations, Du shared complaints about her difficult life, and as the two talked more and more, Zhu began transferring small amounts of money to help. Over time, Du said she needed money for various things—from financial support for school to legal disputes and expensive medical treatments for family members. Between 2022 and 2023, Zhu claims she transferred nearly 200,000 yuan in total.

At the end of 2023, Zhu–who works as a taxi driver–urgently needed money due to a family crisis. She reached out to Du to ask if she could repay the money. According to Zhu, she only returned 30,000 yuan (US$4,180) and refused to pay more, even though at the same time, Du was allegedly flaunting luxury brand purchases and had plans to buy a villa.

On June 25, 2025, Zhu posted an update on her Weibo account, saying she had traveled to Ulanhot City in Inner Mongolia – Du’s hometown – to seek justice and report the case to local authorities.

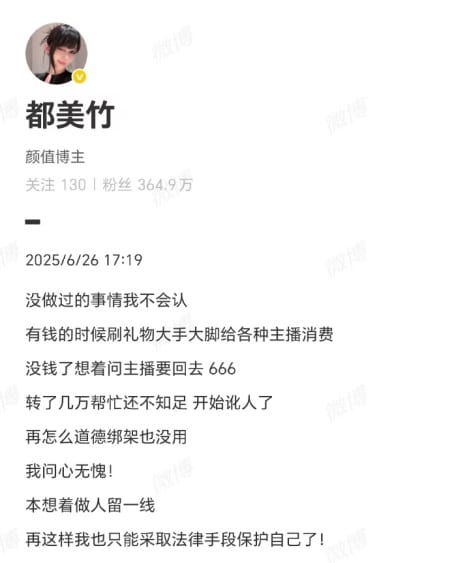

Du Meizhu has responded to the allegations on social media, writing that she “won’t admit to things I haven’t done.” She does not deny that Zhu gave her money.

She writes: “When she had money, she was lavishly spending it on gifts in all kinds of livestreams. Now that she’s broke, she wants it back from the streamers? After I transferred her thousands of yuan, she’s still not satisfied and is now starting to extort me. No amount of moral pressure will work. I have a clear conscience!”

The post by Du Meizhu

The case has blown up online. One post by Ms. Zhu has already received over 133,000 likes and is still gaining traction.

But the developments surrounding the case are puzzling to some. Du Meizhu has long maintained a social media image of wealth, showcasing a lifestyle filled with Dubai travel, horseback riding, luxury food, and fashion. Why would she need to take money from a single mum? Du is being criticized not only for faking her wealth, but also for accepting so much money from a woman who clearly needed the money for her own family.

Du Meizhu social media photos.

Although the story is attracting a lot of attention online because it exposes private conversations between Du and the woman – and, frankly, many netizens just enjoy the drama, – it also says a lot about China’s thriving livestreaming industry and just how close online followers can feel to the influencers they follow. In these kinds of online communities, it is common for fans and followers to send livestreamers money or ‘virtual gifts’.

In the case of Ms. Zhu, some netizens doubt that she can prove in court that she loaned Du the money instead of gifting it to her. People also criticize Zhu: why did she spend so much money on an online influencer instead of on her own daughter?

Either way, many Chinese netizens feel that it was not right of Du Meizhu to take advantage of a single mum like that. Even if she’s not legally wrong, they feel she lacks moral integrity.

Du’s most recent social media post—featuring her in so-called “old money fashion” outfits—has only added fuel to the fire. Dozens of commenters flooded the post with demands that she repay Ms. Zhu. Though Du seemingly tried to delete the negative comments, they kept pouring in. “At this rate, there won’t be any comments left,” one user wrote.

Whether or not Du Meizhu ultimately faces legal consequences, the backlash is already taking a toll. She might escape the courtroom, but won’t be able to escape the court of public opinion.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Celebs

Earring Gate: Huang Yangdiantian and the 2.3 Million RMB Emerald Earrings

Online sleuths connect emerald earrings to post-earthquake business ties—sparking official investigations.

Published

5 months agoon

May 25, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

Dear Reader,

This week, the Chinese internet exploded over a pair of earrings worn by a child actress.

In recent years, China’s netizens have been paying closer attention to so-called “nepo babies”—the children of the rich and powerful whose success often seems tied more to family connections than to talent.

Some, like Huawei’s heiress Yao Anna (姚安娜), have been criticized for using family ties to enter the entertainment industry. Others, like the infamous “Miss Dong” in the recent medical scandal, have sparked public outrage for abusing privilege to bend academic rules.

Facing economic difficulties and a tough job market, the public’s tolerance for nepotism and corruption is running increasingly thin. But when these issues touch on national trauma, including natural disasters and charity efforts, the public anger runs even deeper.

That’s why a Chinese teenage actress named Huang Yangdiantian (黄杨钿甜) recently found herself at the center of an online storm.

Earring Gate: Behind the Sparkle

Huang, born in 2007, started her career as a child actress in the 2017 historical drama Princess Agents (楚乔传).

She later gained more popularity by starring in other hit series, including Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace (如懿传), and also built an online following.

The recent scandal broke out after Huang shared a series of photos on Xiaohongshu, where she has around 328,000 followers. In the photos, meant to celebrate her 18th birthday, she’s seen proudly wearing a pair of sparkly emerald earrings. In the caption, she mentioned they belonged to her mom.

Sharp-eyed netizens quickly identified the earrings as a pair from the British luxury brand Graff—worth a jaw-dropping 2.3 million RMB (319,000 USD).

Digging deeper, online sleuths also found a Weibo post from 2018 showing Huang’s mother wearing a Cartier bracelet, which now retails for around 450,000 RMB (62,400 USD).

Considering Huang’s limited acting experience and modest earnings as a child actress, these luxury items raised eyebrows—and questions about where the family’s wealth was really coming from.

The “online detectives” didn’t stop there. They discovered that Huang’s father, Yang Wei (杨伟), was once a public official in Ya’an City (雅安市), Sichuan Province. After a major 7.0-magnitude earthquake struck Yan’an in 2013 (the Lushan Earthquake), Yang was reportedly involved in post-earthquake reconstruction projects, including investment and tendering.

Interestingly, in 2014, just a year after the earthquake, Huang’s family registered a film and culture company in Shenzhen with 5 million RMB (694,000 USD) in capital. Initially, the company’s legal representative was Huang’s uncle, followed by her mother in 2016. But after Yang resigned from public service, he took over as the official legal representative.

During the pandemic in 2020, Yang also registered a biotech company, which was later rebranded as a beauty and cosmetics trading business. The timing—one company during post-quake reconstruction, then another during a global health crisis—raised suspicions about whether Yang was using national emergencies as business opportunities.

It was also discovered that the Yang family currently lives in a luxury villa in one of Shenzhen’s most upscale neighborhoods, valued at over 100 million RMB (approximately 13.8 million USD).

How did Yang get enough money to start such companies and purchase a multi-million yuan villa? Even if all his official work and business ventures were legitimate, netizens pointed out it still wasn’t enough to explain the family’s enormous wealth.

Huang’s Father Responds, Netizens Dig Deeper

As the controversy grew, Huang’s father responded on May 16 via Weibo, using an account simply named “Huang Yang’s Dad” (黄杨爸爸).

In his post, he claimed that the emerald earrings were fake and of little value. He acknowledged having worked for the Yan’an government but denied any involvement in post-earthquake work, saying the online accusations against him were a case of mistaken identity—“just someone with the same name.” He even added, “I’ve never been corrupt—feel free to report me.”

But the “same name” defense didn’t hold up for long.

In a second wave of ‘detective work’ by online sleuths, netizens found a phone number listed under the name “Yang Wei” on a government website related to post-earthquake reconstruction projects in Ya’an. Some tried sending a small transfer to this number via Alipay, revealing that the profile picture linked to that account was a photo of Huang and her mother when she was younger, immediately making his “same name” explanation completely implausible.

Soon after, the account could no longer be found on Alipay, but because the number was likely tied to many services and platforms, it wasn’t easy to erase entirely. People quickly traced the same phone number to Yang’s accounts on other platforms. Around the same time, the legal representatives of the family’s companies were abruptly changed, only further fueling public suspicion.

Huang’s talent agency issued a statement calling the online rumors false but didn’t offer any concrete evidence to back that up.

By now, a local investigation by the Ya’an Discipline Inspection Commission has confirmed that Yang engaged in illegal business activities and that the birth of his second child (Huang’s younger brother) violated the one-child policy still in effect during his time as a government official. However, the investigation also denied any misappropriation of post-earthquake reconstruction funds. (link).

Most netizens find that many key questions are still left unanswered, and continue to investigate and dissect every single detail relating to Yang, Huang, and the earrings.

More than Online Gossip: Privilege & Public Grief

Some argue that the online speculation surrounding this case has now gone too far.

But for many Chinese netizens, especially younger ones, this isn’t just another scandal passively consumed by the so-called “melon-eating masses” (吃瓜群众). It strikes a nerve because it brings together several sensitive issues all at once.

Although China’s “nepotism babies” frequently spark backlash, they’re also everywhere, from business and entertainment to political and academic circles. For years, the fù èr dài (富二代), or “second-generation rich”—children of those who built fortunes after China’s economic reforms in 1978—have drawn criticism for flaunting wealth and behaving irresponsibly.

Through the years, new terms have been added to China’s nepotism lexicon: there’s xīng èr dài (星二代), referring to the children of celebrities; guān èr dài (官二代), a negative label for the children of government officials or bureaucrats; and hóng èr dài (红二代) and jūn èr dài (军二代), used to describe the children of political elites and military families.

Nepotism is closely tied to corruption—another painful issue in society that surfaces time and again. It’s particularly sensitive because it undermines more than just trust in (local) leadership; it erodes faith in meritocracy and leads the public to question the fairness of the entire system.

When these kinds of issues become entwined with national disasters and charity work—where the already privileged are seen to illegally profit from public grief for private gain—it becomes more than just a breach of public trust. It crosses a moral red line in the most extreme way.

For many young Chinese today, earthquake disasters are not distant history – they’re part of a shared collective memory that still strikes a nerve. In the comment sections of related news posts these days, many netizens recall donating money and supplies to earthquake relief efforts, now wondering whether their goodwill ever truly reached those in need.

The timing has only added fuel to the fire. The controversy erupted around the 17th anniversary of the devastating 2008 Wenchuan earthquake (5.12). Though that disaster is different from the 2013 earthquake, both struck Ya’an City, and public discussions has started to lump them together, bringing back old memories and concerns about disaster relief and public trust.

Back in 2009, Professor Deng Guosheng (邓国胜) from Tsinghua University studied where the 76.7 billion RMB (about 10.5 billion USD) in Wenchuan relief donations had gone. He found that nearly 80% of the money was controlled by the government or groups linked to it, like the Red Cross, with little transparency on how it was spent. People basically have no idea how the money they donated was spent.

In light of the recent controversy, Deng’s study and its numbers are being brought up again in many threads across Chinese social media. Today, as much as 15 years ago, the call for transparancy on how the public’s money is being used in the post-disaster time period is just as relevant.

One Weibo commenter wrote: “For context, in all of 2024, Ya’an City’s general public budget revenue was 8.4 billion RMB in total. This means that the total amount of donations and supplies after the 2008 earthquake was equivalent to 25 years of Ya’an’s current public budget revenue!” He later added: “It’s really not unreasonable at all for the public to ask questions about the authenticity of a pair of 2.3 million RMB earrings.”

Others agree: “It’s absolutely valid for everyone to focus on whether Huang Yangdiantian’s father was involved in embezzlement or bribery (..) When it comes to a tragic event like the Wenchuan earthquake, claims should especially be backed by solid evidence.”

The speculation about Huang’s family wealth goes well beyond celebrity gossip or a “nepo baby” narrative; it reflects a deeper call for clean governance and stricter oversight of how public and charitable funds are managed and spent.

As for Huang, the consequences of her glamorous photoshoot and the controversy it sparked are already unfolding. While her father has now become the target of further formal investigation by disciplinary authorities, it’s rumored that Huang has been removed as the female lead for the historical drama Peacock Bone (雀骨), as well as casting uncertainty over the viability of some of her upcoming projects.

At least we almost certainly know one thing: she won’t be wearing those earrings again any time soon.

Best,

Ruixin Zhang & Manya Koetse

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

Nanchang Crowd Confuses Fan for Knife — Man Kicked Down and Taken Away

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

China’s National Day Holiday Hit: Jingdezhen’s “Chicken Chop Bro”

Evil Unbound (731): How a Chinese Anti-Japanese War Film Backfired

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Rising Online Movement for Smoke-Free Public Spaces in China

China Trend Watch: Pagoda Fruit Backlash, Tiananmen Parade Drill & Alipay Outage (Aug 11–12)

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral3 months ago

China Memes & Viral3 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature11 months ago

China Books & Literature11 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral10 months ago

China Memes & Viral10 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained