China Society

“Elderlies” in Their Thirties: The Growing Interest of Chinese Youth in Nursing Homes

Some Chinese nursing homes are evolving into sought-after havens where China’s younger people can “lie flat” without worrying about meals and household chores, while enjoying a high-quality lifestyle.

Published

2 years agoon

By

Zilan Qian

Chinese nursing homes are changing their image in the social media age. While Chinese vloggers experiment with living in old people’s homes, and nursing homes are modernizing their facilities, some senior care centers are offering young people the chance to reside in their communities for free – as long as they spend some time with their elderly residents.

In China, nursing homes (养老院, yǎnglǎoyuàn) are usually not linked to lively living spaces. Many picture elderly residents trapped in dull daily routines, lacking companionship, without any visitors or children around, simply awaiting the inevitable alone.

However, these places, once synonymous with boredom, loneliness, and the end of life, are now piquing the interest of younger generations in China, breathing new life into them and transforming them into more vibrant living communities.

Recently, a nursing home in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, began to recruit young people to live there. The initiative is a part of the “Companion Aging Program” promoted by the local civil affair bureau.

Its objective is twofold. One the one hand, it provides new living environments for younger generations facing difficulties in securing housing. On the other hand, it alleviates the burden of social isolation on seniors who struggle to stay in touch with the communities around them.

The program is focused on attracting young people, especially those who have just entered the workforce. They can stay in one-bedroom apartments within nursing homes for free, with only a small monthly management fee of 300 yuan ($41). The only requirement is that they spend at least ten hours each month engaging in activities with elderly residents, like sharing meals, going for walks, or having conversations.

A young resident is accompanying an elderly at the nursing home. Image via The Paper.

The government initiators stress the program’s win-win situation. A staff member at the bureau explains, “The program can provide accompany to satisfy seniors’ emotional needs, while also helping ‘companions’ to save on rental costs.”

To ensure that the program is indeed mutually beneficial, the government has established specific criteria for potential senior companions. These requirements include not having current residents in the city, holding at least a junior college education level, and having desirable backgrounds in fields such as medicine, psychology, information technology, arts, or law.

The program has been well-received thus far. In a Weibo poll with the hashtag “Are you willing to live in nursing homes for free by accompanying old people?” (#你愿意陪伴老年人免费入住养老院吗#), initiated by Xinjin News (@新京报), 55% of the respondents wholeheartedly support the initiative, while approximately 30% remain undecided.

According to another recent Weibo post by Sina News, the nursing home has already received hundreds of resumes from applicants.

“The Old Man in His Thirties”: Young People Who Want to Live in Nursing Homes

In the meantime, living in nursing homes seems to have become increasingly popular among young people in China, even when it’s not always free of charge. Nursing homes have not only been portrayed in more favorable lights on social media by state media outlets, they have also taken proactive measures themselves to improve their image.

Thanks to these collective efforts, what were once seen as lonely and uninspiring places are now seemingly transforming into popular residences where China’s younger people can “lie flat” (read more), without worrying about meals and household chores, while enjoying a high-quality lifestyle.

On social app Xiaohongshu, one user named “The Old Man in His Thirties” (三旬老汉) has recently been documenting his experience of moving to a nursing home.

In his first video, somewhat jokingly, he talks about quitting his job due to overwhelming work demands and choosing to embrace a “lie-flat” lifestyle (“躺平”). He was drawn to the nursing home because it provides meals, takes care of residents, and handles daily chores.

Titled “Day xx of living in a nursing home at the age of thirty” (“三十岁入住养老院的第xx天”), his subsequent videos showcase the nursing home staff preparing delicious meals for him, getting him snacks, and even engaging in esports activities with him. These videos also feature his humorous interactions with his roommate, a senior resident in his seventies.

Another post-95 generation Xiaohongshu user (久久姨家政) recently also shared his experiences of living in an old people’s home. His videos revolve around talking to older residents, enjoying meals with them or joking around. There are also other accounts, all young Chinese vloggers, sharing their own journeys of moving into senior care facilities.

This 25-year-old vlogger shared his experiences of living in a nursing home.

Although these videos are apparently filmed based on written scripts, many netizens still see the attractiveness of nursing homes through these kinds of videos and posts. Many viewers have left comments under these videos expressing their desire to reside in senior living communities, asking for locations and inquiring about the costs.

Since the first video by “The Old Man in His Thirties” was posted in mid-June, the series has documented approximately 70 days of life in the nursing home. By now, the account has nearly 60,000 followers, and the videos accumulated thousands of likes.

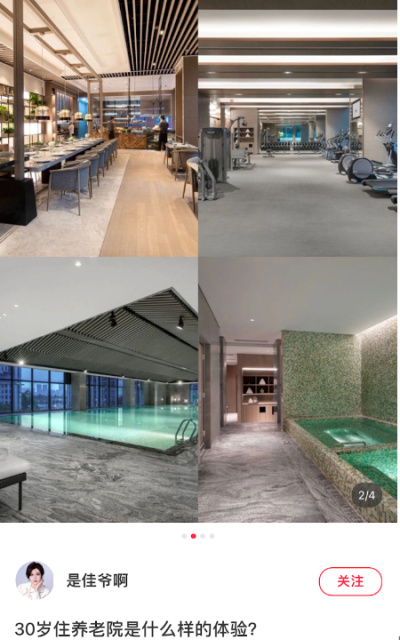

In addition to improving their image through social media, some nursing homes in China have also enhanced their appeal by upgrading facilities. Gyms, swimming pools, snooker tables, free wifi and esports rooms – a variety of amenities have been introduced to transform nursing homes into modern spaces that also cater to the preferences of younger individuals.

Some private nursing homes also market themselves as “nursing homes even young people would want to live in,” emphasizing the exceptional quality and modern standards of services and facilities.

A Xiaohongshu blogger promoting a private nursing home equipped with gyms, swimming pools, and spa services under the title “what does it feel like to live in nursing homes in the thirties?”

This online promotion has had the surprising by-effect that younger and middle-aged people are also changing their attitudes about moving into nursing homes when they are old and retired.

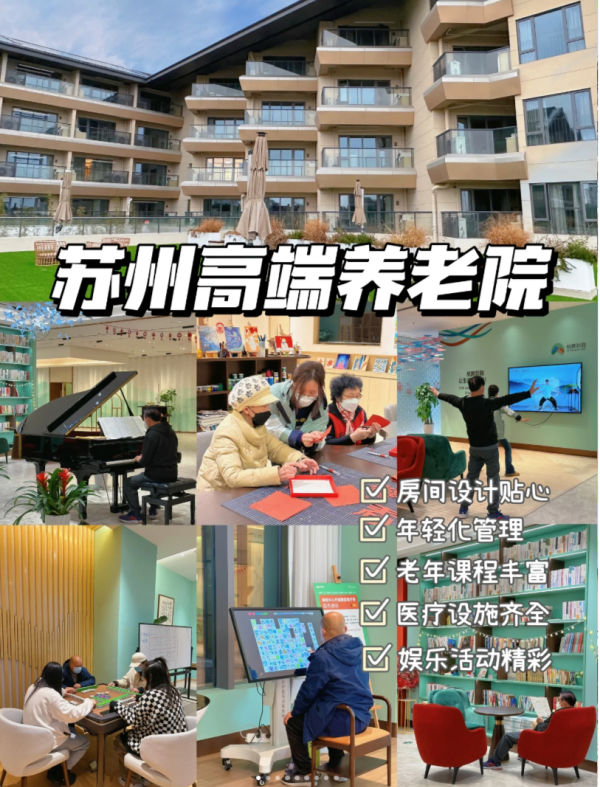

Hiaohongshu user experiencing life in a nursing home in Suzhou: “I’m only 20 years old and living in an old people’s home already!”

While some nursing homes across the country are offering free short stays for young Chinese, other individuals have gone as far as paying for a short stay to personally experience various nursing homes. One Xiaohongshu user, after spending a night at a local upscale nursing home and sharing her experience with a friend, commented, “After the immersive experience, I’m eager to apply for long-term residency right away.”

A Path to Change Eldercare in Aging China

The growing interest of young people in nursing homes is not merely a coincidental trend arising from local government initiatives or viral social media trends.

Elderly care services have been a significant focal point of China’s national strategies for several years, driven by the projected fourfold increase in the elderly population, from 36 million to 150 million, in the next three decades.

In early May of this year, the government issued guidelines aimed at establishing a comprehensive elderly care system by 2025. These guidelines emphasize the provision of material support to elderly individuals living alone, which includes the improvement of services and facilities within nursing homes.

This increased focus on nursing homes may indicate a shift in China’s eldercare strategies, particularly in light of the significant decline in birth rates. From 2011 to 2020, China prioritized a home-based eldercare system, encouraging younger generations to live in close proximity to their elderly relatives through restructured healthcare facilities and the promotion of filial piety.

Between 2015 and 2020, the central government allocated 5 billion yuan (approximately USD 743 million) to support new pilot programs for home-based elderly care services (Krings et al 2022).

However, with record-low marriage and birth rates, it is likely that a significant number of young people today will later lack the younger family members needed to provide home-based care as they age. Consequently, nursing homes are bound to play a more crucial role in China’s future eldercare industry.

Xiaohongshu post promoting a Suzhou high-end nursing home.

In Chinese society, older adults residing in nursing homes are often regarded as examples of personal failures for not having loving families with caring children (Luo & Zhan 2911). Moreover, concerns about potential mistreatment of vulnerable elderly residents by staff members at nursing homes persist.

The increasing interest and recent active involvement of young people in nursing homes offer a way to challenge old stereotypes and bring new ideas to the changing eldercare landscape in China. Perhaps most importantly, it helps combat the loneliness that many seniors face while bridging the gap between the country’s younger and older generations.

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

References (other sources hyperlinked in text):

Krings, Marion F., Jeroen D. van Wijngaarden, Shasha Yuan, and Robbert Huijsman. 2022. “China’s Elder Care Policies 1994–2020: A Narrative Document Analysis.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6141.

Luo, Baozhen, and Heying Zhan. 2011. “Filial Piety and Functional Support: Understanding Intergenerational Solidarity among Families with Migrated Children in Rural China.” Ageing International 37, no. 1: 69–92.

This article has been edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Zilan Qian is a China-born undergraduate student at Barnard College majoring in Anthropology. She is interested in exploring different cultural phenomena, loves people-watching, and likes loitering in supermarkets and museums.

China ACG Culture

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

From ugly-cute rebellion to a new kind of ‘C-pop,’ the breakout success of Wakuku sheds light on Chinese consumer culture and the forces driving China’s trend toy industry.

Published

1 week agoon

July 6, 2025

Wakuku is the most talked-about newcomer in China’s trend toy market. Besides its mischievous grin, what’s perhaps most noteworthy is how closely Wakuku follows the marketing success of Labubu. As the strongest new designer toy of 2025, Wakuku says a lot about China’s current creative economy — from youth-led consumer trends to hybrid business models.

As it is becoming increasingly clear that Chinese designer toy Labubu has basically conquered the world, it’s already time for the next made-in-China collectible toy to start trending on Chinese social media.

Now, the name that’s trending is Wakuku, a Chinese trend toy created by the Shenzhen-based company Letsvan.

In March 2025, a new panda-inspired Wakuku debuted at Miniso Land in Beijing, immediately breaking records and boosting overall store revenue by over 90%. Wakuku also broke daily sales records on May 17 with the launch of its “Fox-and-Bunny” collab at Miniso flagship stores in Shanghai and Nanjing. At the opening of the Miniso Space in Nanjing on June 18, another Wakuku figure sold out within just two hours. Over the past week, Wakuku went trending on Chinese social media multiple times.

From left to right: the March, May, and June successful Wakuku series/figurines

Like Labubu, Wakuku is a collectible keychain doll with a soft vinyl face and a plush body. These designer toys are especially popular among Chinese Gen Z female consumers, who use them as fashion accessories (hanging them from bags) or as desk companions.

We previously wrote in depth about the birth of Labubu, its launch by the Chinese POP MART (founded 2010), and the recipe for its global popularity in this article, so if you’re new to this trend of Chinese designer toys, you’ll want to check it out first (link).

Labubu has been making international headlines for months now, with the hype reaching a new peak when a human-sized Labubu sold for a record 1.08 million RMB (US$150,700), followed by a special edition that was purchased for nearly 760,000 RMB (US$106,000).

Now, Wakuku is the new kid on the block, and while it took Labubu nine years to win over young Chinese consumers, it barely took Wakuku a year — the character was created in 2022–2023, made its retail debut in 2024, and went viral within months.

Its pricing is affordable (59–159 RMB, around $8.2-$22) and some netizens argue it’s more quality for money.

While Labubu is a Nordic forest elf, Wakuku is a tribal jungle warrior. It comes in various designs and colors depending on the series and is sold in blind boxes (盲盒), meaning buyers don’t know exactly which design they’re getting — which adds an element of surprise.

➡️ There’s a lot to say about Wakuku, but perhaps the most noteworthy aspect is how closely it mirrors the trajectory of POP MART’s Labubu.

Wakuku’s recent success in China highlights the growing appeal and rapid rise of Chinese IPs (beyond its legal “intellectual property” meaning, ‘IPs’ is used to refer to unique cultural brands, characters, or stories that can be developed into collectibles, merchandise, and broader pop culture phenomena).

Although many critics predict that the Labubu trend will blow over soon, the popularity of Wakuku and other Labubu-like newcomers shows that these toys are not just a fleeting craze, but a cultural phenomenon that reflects the mindset of young Chinese consumers, China’s cross-industry business dynamics, and the global rise of a new kind of ‘C-pop.’

Wakuku: A Cheeky Jungle Copycat

When I say that Wakuku follows POP MART’s path almost exactly, I’m not exaggerating. Wakuku may be portrayed as a wild jungle child, but it’s definitely also a copycat.

It uses the same materials as Labubu (soft vinyl + plush), the name follows the same ABB format (Labubu, Wakuku, and the panda-themed Wakuku Pangdada), and the character story is built on a similar fantasy universe.

In fact, Letsvan’s very existence is tied to POP MART’s rise — the company was only founded in 2020, the same year POP MART, then already a decade old, went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and became a dominant industry force.

In terms of marketing, Wakuku imitates POP MART’s strategy: blind boxes, well-timed viral drops, limited-edition tactics, and immersive retail environments.

It even follows a similar international expansion model as POP MART, turning Thailand into its first stop (出海首站) — not just because of its cultural proximity and flourishing Gen Z social media market, but also because Thailand was one of the first and most successful foreign markets for Labubu.

Its success is also deeply linked to celebrity endorsement. Just as Labubu gained global traction with icons like BLACKPINK’s Lisa and Rihanna seen holding the doll, Wakuku too leans heavily on celebrity visibility and entertainment culture.

Like Labubu, Wakuku even launched its own Wakuku theme song.

Since 2024, Letsvan has partnered with Yuehua Entertainment (乐华娱乐) — one of China’s leading talent agencies — to tap into its entertainment resources and celebrity network, powering the Wakuku marketing engine. Since stars like Esther Yu (虞书欣) were spotted wearing Wakuku as a jeans hanger, demand for the doll skyrocketed. Yuehua’s founder, Du Hua (杜华), even gifted a Wakuku to David Beckham as part of its celebrity strategy.

From Beckham to Esther Yu; celebrity endorsements play a big role in the viral marketing of Wakuku.

But what’s most important in Wakuku’s success — and how it builds on Labubu — is that it fully embraces the ugly-cute (丑萌 chǒu méng) aesthetic. Wakuku has a mischievous smile, expressive eyes, a slightly crooked face, a unibrow, and freckles — fitting perfectly with what many young Chinese consumers love: expressive, anti-perfectionist characters (反精致).

“Ugly-Cute” as an Aesthetic Rebellion

Letsvan is clearly riding the wave of “ugly trend toys” (丑萌潮玩) that POP MART spent years cultivating.

🔍 Why are Chinese youth so obsessed with things that look quirky or ugly?

A recent article by the Beijing Science Center (北京科学中心) highlights how “ugly-cute” toys like Labubu and Wakuku deviate from traditional Chinese aesthetics, and reflect a deeper generational pushback against perfection and societal expectations.

The pressure young people face — in education, at work, from family expectations, and information overload — is a red thread running through how China’s Gen Z behaves as a social media user and consumer (also see the last newsletter on nostalgia core).

To cope with daily stress, many turn to softer forms of resistance, such as the “lying flat” movement or the sluggish “rat lifestyle” in which people reject societal pressures to succeed, choosing instead to do the bare minimum and live simply.

This generational pushback also extends to traditional norms around marriage, gender roles, and ideals of beauty. Designer toys like Labubu and Wakuku are quirky, asymmetrical, gender-fluid, rebellious, and reflect a broader cultural shift: a playful rejection of conformity and a celebration of personal expression, authenticity, and self-acceptance.

Another popular designer toy is Crybaby, designed by Thai designer Molly, and described as follows: “Crybaby is not a boy or a girl, it is not even just human, it represents an emotion that comes from deep within. It can be anything and everything! Laughter isn’t the only way to make you feel better, crying can be healing too. If one day, a smile can’t alleviate your problems, baby, let’s cry together.”

But this isn’t just about rejecting tradition. It’s also about seeking happiness, comfort, and surprise: emotional value. And it’s usually not brand-focused but influencer-led. What matters is the story around it and who recommends it (unless the brand becomes the influencer itself — which is what’s ultimately happening with POP MART).

One of the unofficial ambassadors of the chǒu méng ugly-cute trend is Quan Hongchan (全红婵), the teenage diving champion and Olympic gold medallist from Guangdong. Quan is beloved not just for her talent, but also for her playful, down-to-earth personality.

During the Paris Olympics, she went viral for her backpack, which was overflowing with stuffed animals (some joked she was “carrying a zoo on her back”) — and for her animal-themed slippers, including a pair of ugly fish ones.

Quan Hongchan with her Wakuku, and her backpack and slippers during her Paris Olympics days.

It’s no surprise that Quan Hongchan is now also among the celebrities boosting the popularity of the quirky Wakuku.

From Factory to Fandom: A New Kind of “C-pop” in the Making

The success of Wakuku and other similar toys shows that they’re much more than Labubu 2.0; they’re all part of a broader trend tapping into the tastes and values of Chinese youth — which also speaks to a global audience.

And this trend is serious business. POP MART is one of the world’s fastest-growing consumer brands, with a current market value of approximately $43 billion, according to Morgan Stanley.

No wonder everyone wants a piece of the ‘Labubu pie,’ from small vendors to major companies.

It’s not just the resellers of authentic Labubu dolls who are profiting from the trend — so are the sellers of ‘Lafufu,’ a nickname for counterfeit Labubu dolls, that have become ubiquitous on e-commerce platforms and in toy markets (quite literally).

Wakuku’s rapid rise is also a story of calculated imitation. In this case, copying isn’t seen as a flaw but as smart market participation.

The founding team behind Letsvan already had a decade of experience in product design before setting out on their journey to become a major player in China’s popular designer toy and character merchandise market.

But their real breakthrough came in early 2025, when QuantaSing (量子之歌), a leading adult learning ed-tech company with no previous ties to toys, acquired a 61% stake in the company.

With QuantaSing’s financial backing, Yuehua Entertainment’s marketing power, and Miniso’s distribution reach, Wakuku took it to the next level.

The speed and precision with which Letsvan, QuantaSing, and Wakuku moved to monetize a subcultural trend — even before it fully peaked — shows just how advanced China’s trend toy industry has become.

This is no longer just about cute (or ugly-cute) designs; it’s about strategic ecosystems by ‘IP factories,’ from concept and design to manufacturing and distribution, blind-box scarcity tactics, immersive store experiences, and influencer-led viral campaigns — all part of a roadmap that POP MART refined and is now adopted by many others finding their way into this lucrative market. Their success is powered by the strength of China’s industrial & digital infrastructure, along with cross-industry collaboration.

The rise of Chinese designer toy companies reminds of the playbook of K-pop entertainment companies — with tight control over IP creation, strong visual branding, carefully engineered virality, and a deep understanding of fandom culture. (For more on this, see my earlier explanation of the K-pop success formula.)

If K-pop’s global impact is any indication, China’s designer toy IPs are only beginning to show their potential. The ecosystems forming around these products — from factory to fandom — signal that Labubu and Wakuku are just the first wave of a much larger movement.

– By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Celebs

Earring Gate: Huang Yangdiantian and the 2.3 Million RMB Emerald Earrings

Online sleuths connect emerald earrings to post-earthquake business ties—sparking official investigations.

Published

2 months agoon

May 25, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

Dear Reader,

This week, the Chinese internet exploded over a pair of earrings worn by a child actress.

In recent years, China’s netizens have been paying closer attention to so-called “nepo babies”—the children of the rich and powerful whose success often seems tied more to family connections than to talent.

Some, like Huawei’s heiress Yao Anna (姚安娜), have been criticized for using family ties to enter the entertainment industry. Others, like the infamous “Miss Dong” in the recent medical scandal, have sparked public outrage for abusing privilege to bend academic rules.

Facing economic difficulties and a tough job market, the public’s tolerance for nepotism and corruption is running increasingly thin. But when these issues touch on national trauma, including natural disasters and charity efforts, the public anger runs even deeper.

That’s why a Chinese teenage actress named Huang Yangdiantian (黄杨钿甜) recently found herself at the center of an online storm.

Earring Gate: Behind the Sparkle

Huang, born in 2007, started her career as a child actress in the 2017 historical drama Princess Agents (楚乔传).

She later gained more popularity by starring in other hit series, including Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace (如懿传), and also built an online following.

The recent scandal broke out after Huang shared a series of photos on Xiaohongshu, where she has around 328,000 followers. In the photos, meant to celebrate her 18th birthday, she’s seen proudly wearing a pair of sparkly emerald earrings. In the caption, she mentioned they belonged to her mom.

Sharp-eyed netizens quickly identified the earrings as a pair from the British luxury brand Graff—worth a jaw-dropping 2.3 million RMB (319,000 USD).

Digging deeper, online sleuths also found a Weibo post from 2018 showing Huang’s mother wearing a Cartier bracelet, which now retails for around 450,000 RMB (62,400 USD).

Considering Huang’s limited acting experience and modest earnings as a child actress, these luxury items raised eyebrows—and questions about where the family’s wealth was really coming from.

The “online detectives” didn’t stop there. They discovered that Huang’s father, Yang Wei (杨伟), was once a public official in Ya’an City (雅安市), Sichuan Province. After a major 7.0-magnitude earthquake struck Yan’an in 2013 (the Lushan Earthquake), Yang was reportedly involved in post-earthquake reconstruction projects, including investment and tendering.

Interestingly, in 2014, just a year after the earthquake, Huang’s family registered a film and culture company in Shenzhen with 5 million RMB (694,000 USD) in capital. Initially, the company’s legal representative was Huang’s uncle, followed by her mother in 2016. But after Yang resigned from public service, he took over as the official legal representative.

During the pandemic in 2020, Yang also registered a biotech company, which was later rebranded as a beauty and cosmetics trading business. The timing—one company during post-quake reconstruction, then another during a global health crisis—raised suspicions about whether Yang was using national emergencies as business opportunities.

It was also discovered that the Yang family currently lives in a luxury villa in one of Shenzhen’s most upscale neighborhoods, valued at over 100 million RMB (approximately 13.8 million USD).

How did Yang get enough money to start such companies and purchase a multi-million yuan villa? Even if all his official work and business ventures were legitimate, netizens pointed out it still wasn’t enough to explain the family’s enormous wealth.

Huang’s Father Responds, Netizens Dig Deeper

As the controversy grew, Huang’s father responded on May 16 via Weibo, using an account simply named “Huang Yang’s Dad” (黄杨爸爸).

In his post, he claimed that the emerald earrings were fake and of little value. He acknowledged having worked for the Yan’an government but denied any involvement in post-earthquake work, saying the online accusations against him were a case of mistaken identity—“just someone with the same name.” He even added, “I’ve never been corrupt—feel free to report me.”

But the “same name” defense didn’t hold up for long.

In a second wave of ‘detective work’ by online sleuths, netizens found a phone number listed under the name “Yang Wei” on a government website related to post-earthquake reconstruction projects in Ya’an. Some tried sending a small transfer to this number via Alipay, revealing that the profile picture linked to that account was a photo of Huang and her mother when she was younger, immediately making his “same name” explanation completely implausible.

Soon after, the account could no longer be found on Alipay, but because the number was likely tied to many services and platforms, it wasn’t easy to erase entirely. People quickly traced the same phone number to Yang’s accounts on other platforms. Around the same time, the legal representatives of the family’s companies were abruptly changed, only further fueling public suspicion.

Huang’s talent agency issued a statement calling the online rumors false but didn’t offer any concrete evidence to back that up.

By now, a local investigation by the Ya’an Discipline Inspection Commission has confirmed that Yang engaged in illegal business activities and that the birth of his second child (Huang’s younger brother) violated the one-child policy still in effect during his time as a government official. However, the investigation also denied any misappropriation of post-earthquake reconstruction funds. (link).

Most netizens find that many key questions are still left unanswered, and continue to investigate and dissect every single detail relating to Yang, Huang, and the earrings.

More than Online Gossip: Privilege & Public Grief

Some argue that the online speculation surrounding this case has now gone too far.

But for many Chinese netizens, especially younger ones, this isn’t just another scandal passively consumed by the so-called “melon-eating masses” (吃瓜群众). It strikes a nerve because it brings together several sensitive issues all at once.

Although China’s “nepotism babies” frequently spark backlash, they’re also everywhere, from business and entertainment to political and academic circles. For years, the fù èr dài (富二代), or “second-generation rich”—children of those who built fortunes after China’s economic reforms in 1978—have drawn criticism for flaunting wealth and behaving irresponsibly.

Through the years, new terms have been added to China’s nepotism lexicon: there’s xīng èr dài (星二代), referring to the children of celebrities; guān èr dài (官二代), a negative label for the children of government officials or bureaucrats; and hóng èr dài (红二代) and jūn èr dài (军二代), used to describe the children of political elites and military families.

Nepotism is closely tied to corruption—another painful issue in society that surfaces time and again. It’s particularly sensitive because it undermines more than just trust in (local) leadership; it erodes faith in meritocracy and leads the public to question the fairness of the entire system.

When these kinds of issues become entwined with national disasters and charity work—where the already privileged are seen to illegally profit from public grief for private gain—it becomes more than just a breach of public trust. It crosses a moral red line in the most extreme way.

For many young Chinese today, earthquake disasters are not distant history – they’re part of a shared collective memory that still strikes a nerve. In the comment sections of related news posts these days, many netizens recall donating money and supplies to earthquake relief efforts, now wondering whether their goodwill ever truly reached those in need.

The timing has only added fuel to the fire. The controversy erupted around the 17th anniversary of the devastating 2008 Wenchuan earthquake (5.12). Though that disaster is different from the 2013 earthquake, both struck Ya’an City, and public discussions has started to lump them together, bringing back old memories and concerns about disaster relief and public trust.

Back in 2009, Professor Deng Guosheng (邓国胜) from Tsinghua University studied where the 76.7 billion RMB (about 10.5 billion USD) in Wenchuan relief donations had gone. He found that nearly 80% of the money was controlled by the government or groups linked to it, like the Red Cross, with little transparency on how it was spent. People basically have no idea how the money they donated was spent.

In light of the recent controversy, Deng’s study and its numbers are being brought up again in many threads across Chinese social media. Today, as much as 15 years ago, the call for transparancy on how the public’s money is being used in the post-disaster time period is just as relevant.

One Weibo commenter wrote: “For context, in all of 2024, Ya’an City’s general public budget revenue was 8.4 billion RMB in total. This means that the total amount of donations and supplies after the 2008 earthquake was equivalent to 25 years of Ya’an’s current public budget revenue!” He later added: “It’s really not unreasonable at all for the public to ask questions about the authenticity of a pair of 2.3 million RMB earrings.”

Others agree: “It’s absolutely valid for everyone to focus on whether Huang Yangdiantian’s father was involved in embezzlement or bribery (..) When it comes to a tragic event like the Wenchuan earthquake, claims should especially be backed by solid evidence.”

The speculation about Huang’s family wealth goes well beyond celebrity gossip or a “nepo baby” narrative; it reflects a deeper call for clean governance and stricter oversight of how public and charitable funds are managed and spent.

As for Huang, the consequences of her glamorous photoshoot and the controversy it sparked are already unfolding. While her father has now become the target of further formal investigation by disciplinary authorities, it’s rumored that Huang has been removed as the female lead for the historical drama Peacock Bone (雀骨), as well as casting uncertainty over the viability of some of her upcoming projects.

At least we almost certainly know one thing: she won’t be wearing those earrings again any time soon.

Best,

Ruixin Zhang & Manya Koetse

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

Jiehun Huazhai (结婚化债): Getting Married to Pay Off Debts

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

Behind the Mysterious Death of Chinese Internet Celebrity Cat Wukong

Do You Know Who Li Gang Is? Anti-Corruption Official Arrested for Corruption

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

Earring Gate: Huang Yangdiantian and the 2.3 Million RMB Emerald Earrings

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Society10 months ago

China Society10 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoTeam China’s 10 Most Meme-Worthy Moments at the 2024 Paris Olympics

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoAbout Wang Chuqin’s Broken Paddle at Paris 2024