China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

From Tea Farmer to Online Influencer: Uncle Huang and China’s Rural Live Streamers

‘Cunbo’ aka ‘rural livestreaming’ is all the rage. A win-win situation for farmers, viewers, and Alibaba.

Published

5 years agoon

This is the “WE…WEI…WHAT?” column by Manya Koetse, originally published in German by Goethe Institut China on Goethe.de: “VOM TEEBAUERN ZUM INFLUENCER: ONKEL HUANG UND CHINAS LÄNDLICHE LIVESTREAMER.”

The past year has been super tumultuous when it comes to the topics that have been dominating Chinese social media. The Coronavirus crisis was preceded by other big issues that were all the talk online, from the US-China trade war to the protests in Hong-Kong, the swine flu, and heightened censorship and surveillance.

Despite the darker side to China’s online environment, however, there were also positive developments. One of the online trends that became popular this year comes with a term of its own, namely cūnbō (村播): rural livestreaming. Chinese farmers using livestreaming as a way to sell their products and promote their business have become a more common occurrence on China’s e-commerce and social media platforms.

mage via Phoenix News (iFeng Finance).

The social media + e-commerce mix, also called ‘social shopping,’ is booming in the PRC. Online platforms where the lines between social media and e-commerce have disappeared are now more popular than ever. There’s the thriving Xiaohongshu (小红书Little Red Book) platform, for example, but apps such as TikTok (known as Douyin in China) also integrate shopping in the social media experience.

Over recent years, China’s e-commerce giant Alibaba has contributed to the rising popularity of ‘social shopping.’ Its Taobao Live unit (also a separate app), which falls under the umbrella of China’s biggest online marketplace Taobao, is solely dedicated to shopping + social media, mainly mobile-centered. It’s a recipe for success: Chinese mobile users spend over six hours online per day, approximately 72% of them shop online, and nearly 65% of mobile internet users watch livestreaming.

Every minute of every day, thousands of online shoppers tune in to dozens of different channels where sellers promote anything from food products to makeup or pet accessories. The sellers, also called ‘hosts’ or ‘presenters,’ make their channels attractive by incorporating makeup tutorials, cooking classes, giving tips and tricks, chatting away and joking, and promising their buyers the best deal or extra presents when purchasing their products.

Livestreaming on Taobao goes on 24/7 (screenshots from Taobao app by author).

Sometimes thousands of viewers tune in to one channel at the same. They can ‘follow’ their favorite hosts and can interact with them directly by leaving comments on the livestreams. They can compliment the hosts (“You’re so funny!”), ask questions about products (“Does this also come in red?”), or leave practical advice (“You should zoom in when demonstrating this product!”). The product promoted in the livestreams can be directly purchased through the Taobao system.

Over the past year, Alibaba has increased its focus on rural sellers within the livestreaming e-commerce business. Countryside sellers even have their own category highlighted on the Taobao Live app. Chinese tech giant Alibaba launched its ‘cūnbō project’ in the spring of 2019 to promote the use of its Taobao Live app amongst farmers. The most influential livestreaming farmers get signed by Alibaba to elevate Taobao Live’s rural business to a higher level.

One of these influential Chinese farmers who has made a name for himself through livestreaming is Huang Wensheng, a tea farmer from the mountainous Lichuan area in Hunan Province.

Uncle Huang livestreaming from the tea fields (image via Sohu.com)

Huang, who is nicknamed ‘Uncle Farmer,’ sells tea through his channel, where he shows viewers his work and shares stories and songs from his village. He is also known to talk about what he learned throughout his life and will say things such as: “It is important to work hard; not necessarily so much to change the world , but to make sure the world does not change you.”

With just three to five livestreaming sessions per week, ‘Uncle’ Huang reaches up to twenty million viewers per month, and, according to Chinese media reports, has seen a significant increase in his income, earning some 10,000 yuan (€1300) per week.

Huang is not the only farmer from his hometown using Taobao Live to increase their income; there are some hundred rural livestreamers in Lichuan doing the same.

Some random screenshots by author from rural livestreaming channels, where online shoppers get a glimpse of countryside life

The rural livestreaming category is significantly different from the urban fashionistas selling brand makeup and the latest must-haves: these hosts do not have the polished look, glamorous clothes, or stylish backgrounds. They usually film outside while doing their work or offer a glimpse into their often humble rooms or kitchens.

Viewers get to see the source of the products sold by these rural sellers; they often literally go to the fields to show where their agricultural products grow, or film themselves getting the eggs from their chickens or the oranges from the trees. From fruits to potatoes and flowers, and from fresh tea to home-made chili sauce – a wide range of products is promoted and sold through Taobao Live these days.

Some rural livestreamers are trying to stay ahead of their competition by coming up with novel concepts. A young farmer from Sichuan, for example, recently offered viewers the opportunity to “adopt” a rooster from his farm, allowing them to interact with ‘their’ rooster through social media and even throwing the occasional birthday party for some lucky roosters.

Image via sina.com.

Examples such as these show that although the countryside livestreamers usually lack glitter and glam, they can be just as entertaining – or perhaps even more so – than their urban counterparts.

Who benefits from the recent ‘cūnbō’ boom? One could argue that the rising popularity of livestreaming farmers is a win-win situation from which all participants can profit in some way. The commercial interests are big for Alibaba. The company has been targeting China’s countryside for years, as it’s where China’s biggest consumption growth will happen while mobile internet penetration is still on the rise. Alibaba earns profits from an increasing number of rural e-commerce buyers, as well as e-commerce sellers.

Alibaba’s early focus on the countryside as a new home for e-commerce has previously also led to the phenomenon of so-called ‘Taobao Villages,’ where a certain percentage of rural residents are selling local specialties, farm products or other things via the Taobao platform with relatively little transaction costs.

Many Chinese villages and farmers are profiting from the further spread of Taobao in the countryside. Not only does Alibaba invest in logistics and e-commerce trainings in rural areas, these e-commerce channels are also a way to directly boost sales and income for struggling farmers.

Chinese media predict that the rural livestreaming trend will only become more popular in the years to come, bringing forth many more influential farmers like Huang.

But besides the commercial and financial gains that come from the rising popularity of rural livestreamers, there is also a significant and noteworthy social impact. At a time in which China’s rapidly changing society sees a widening gap between urban and rural areas, these rural channels serve as a digital bridge between countryside sellers and urban consumers, offering netizens a real and unpolished look into the lives of farmers in others parts of the country, and gives online buyers more insight and understanding of where their online products came from.

Taobao Live is actually like a traditional “farmers’ market,” but now it is digital, open 24/7, and accessible to anyone with a mobile phone. It’s the Chinese farmers’ market of the 21st century.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

This text was first published by Goethe-Institut China under a CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE license (Creative Commons) as part of a monthly column in collaboration with What’s On Weibo.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China ACG Culture

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Labubu is not ‘Chinese’ at all—and at the same time, it is very much a product of present-day China.

Published

4 weeks agoon

June 8, 2025

Labubu – the hottest toy of 2025 – is making headlines everywhere these days. The little creature is all over TikTok, and from New York to Bangkok and Dubai, people are lining up for hours to get their hands on the popular keyring doll.

In the UK, the Labubu hype has gone so far that its maker temporarily pulled the toys from all of its stores for “safety reasons,” following reports of customers fighting over them. In the Netherlands, the sole store where fans can buy the toys also had to hire extra security to manage the crowds, and Chinese customs authorities have intensified their efforts to prevent the dolls from being smuggled out of the country.

While the Labubu craze had slightly cooled in China compared to its initial peak, the character remains hugely popular and surged back into the top trending charts with the launch of POP MART’s Labubu 3.0 series in late April 2025 (which instantly sold out).

Following the global popularity of the Chinese game Black Myth: Wukong, state media are citing Labubu as another example of a successful Chinese cultural export—calling it ‘a benchmark for China’s pop culture’ and viewing its success as a sign of the globalization of Chinese designer toys.

But how ‘Chinese’ is Labubu, really? Here’s a closer look at its cultural identity and the story behind the trend.

The Journey to Labubu

In the perhaps unlikely case you have never heard of Labubu, I’ll explain: it’s a keyring toy with a naughty and, frankly, somewhat bizarre face and gremlin-like appearance that comes in various colors and variations. It’s mainly loved by young (Gen Z) women, who like to hang the toys on their bags or just keep them as collectibles.

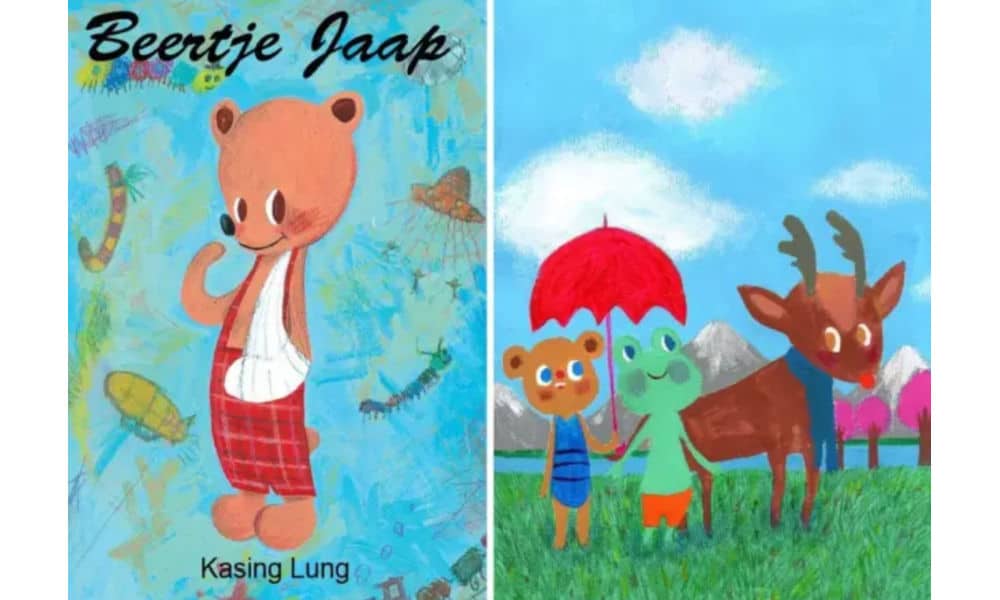

The figurine is based on a character created by renowned Hong Kong-born artist Kasing Lung (龍家昇/龙家升, born 1972), whose work is inspired by Nordic legends of elves.

Kasung Lung, image via Bangkok Post.

Lung’s story is quite inspirational, and very international.

As a child, Lung immigrated to the Netherlands with his parents. Struggling to learn Dutch, young Kasing was given plenty of picture books. The picture books weren’t just a way to connect with his new environment, it also sparked a lifelong love for illustration.

Among Kasing’s favorite books were Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak and those by Edward Gorey — all full of fantasy, with some scary elements and artistic quality.

Later, as his Dutch improved, Kasing became an avid reader and turned into a true bookworm. The many fantasy novels and legendary tales he devoured planted the seed for creating his own world of elves and mythical creatures.

Kasing as a young boy on the right, and one of his children’s illustration books on the left.

After initially returning to Hong Kong in the 1990s, Lung later moved back to the Netherlands and eventually settled in Belgium.

Following a journey of many rejections and persistence, he began publishing his own illustrations and picture books for the European market.

Image via Sina.

In 2010, Hong Kong toy brand How2work’s Howard Lee reached out to Lung. One of How2work’s missions is cultivating creative talent and supporting the Hong Kong art scene. Lee invited Kasung to turn his illustrations into 3D, collectible figurines. Kasung, a collector of Playmobil figures since childhood, agreed to the collaboration for the sake of curiosity and creativity.

Lung’s partnership with How2work marked a transition to toy designer, although Lung also continued to stay active as an illustrator. Besides his own “Max is moe” (Max is tired) picture book, he also did illustrations for a series by renowned Belgian author Brigitte Minne (Lizzy leert zwemmen, Lizzy leert dansen).

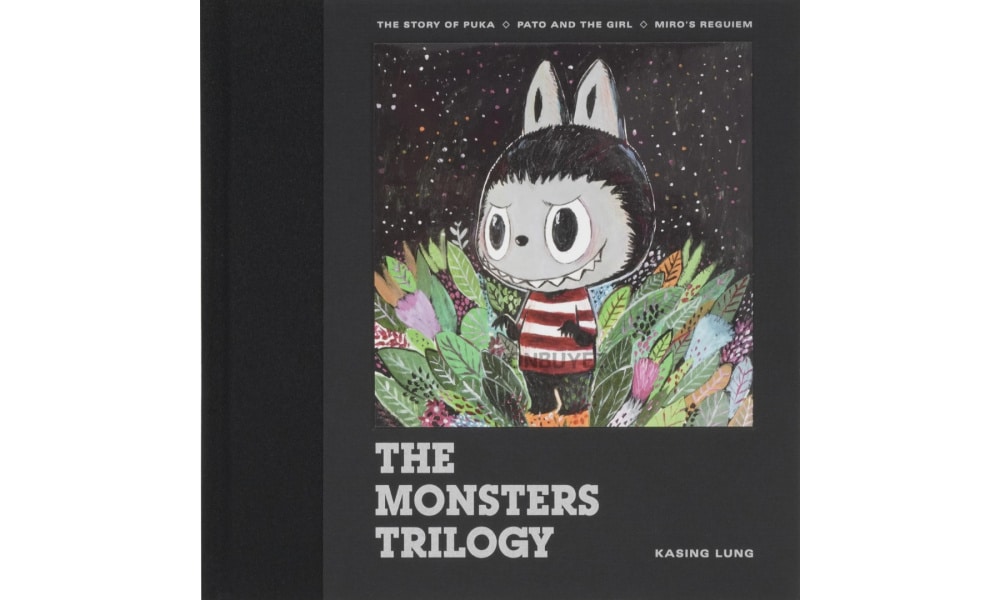

A few years later, Lung introduced what would become known as The Monsters Trilogy: a fantasy universe populated by elf-like creatures. Much like The Smurfs, the Monsters formed a tribe of distinct characters, each with their own personalities and traits, led by a tribal leader named Zimomo.

With its quirky appearance, sharp teeth, and mischievous grin, Labubu stood out as one of the long-eared elves.

When Labubu Met POPMART

Although the Labubu character has been around since 2015, it took some time to gain fame. It wasn’t until Labubu became part of POP MART’s (泡泡玛特) toy lineup in 2019 that it began reaching a mass audience.

POP MART is a Chinese company specializing in artsy toys, figurines, and trendy, pop culture-inspired goods. Founded in 2010 by a then college student, the brand launched with a mission to “light up passion and bring joy,” with a particular focus on young female consumers (15-30 age group) (Wang 2023).

One of POP MART’s most iconic art toy characters—and its first major commercial success—is Molly, designed by Hong Kong artist Kenny Wong in collaboration with How2work.

Prices vary depending on the toy, but small figurines start as low as 34 RMB (about US$5), while collectibles can go as high as 5,999 yuan (US$835). Resellers often charge significantly more.

Pop Mart and its first major commercial success: Molly (source).

POP MART is more than just a store, it’s an operational platform that covers the entire chain of trendy toys, from product development to retail and marketing (Liu 2025).

Within a decade of opening it first store in Beijing, POP MART experienced explosive growth, expanded globally, and was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

The enormous success of POP MART has been the subject of countless marketing studies, drawing various conclusions about how the company managed to hit such a cultural and commercial sweet spot beyond its mere focus on female Gen Z consumers.

🎁 Gamifying consumption | One common conclusion about the success of POP MART, is that it offers more than just products—it offers an experience. At the heart of the brand is its signature blind box model, where customers purchase mystery boxes from specific product lines without knowing which item is inside. Those who are lucky enough will unpack a special ‘hidden edition.’ Originating in Japanese capsule toy culture, this element of surprise gamifies the shopping experience, makes it more shareable on social media, and fuels the desire to complete collections or hunt for rare figures through repeat purchases.

🌍 Creating a POP MART universe | Although POP MART has partnerships with major international brands such as Disney, Marvel, and Snoopy, it places a strong focus on developing its own intellectual property (IP) toys and figurines. In doing so, POP MART has created a universe of original characters, giving them a life beyond the store through things like collaborations, art shows and exhibitions, and even its own theme park in Beijing.

💖 Emotional consumption | What makes POP MART particularly irresistible to so many consumers is the emotional appeal of its toys and collectibles. It taps into nostalgia, cuteness, and aesthetic charm. The toys become companions, either as a desktop buddy or travel buddy. Much of the toys’ value lies in their role as social currency, driven by hype, emotional gratification, and a sense of social bonding and identity (Ge 2024).

The man behind POP MART and its strategy is founder and CEO Wang Ning (王宁), a former street dance champion (!) and passionate entrepreneur with a clear vision for the company. He consistently aims to discover the next iconic design, something that could actually rival Mickey Mouse or Hello Kitty.

In past interviews, Wang has discussed how consumer values are gradually shifting. The rise of niche toys into the mainstream, he says, reflects this transformation. Platforms like Douyin, China’s strong e-commerce infrastructure, and the digital era more broadly have all contributed to changing attitudes, where people are increasingly buying not for utility, but for the sake of happy moments.

While Wang Ning dreams of a more joyful world, he also knows how to make money (with a net worth of $20.3 billion USD, it was actually just announced that he’s Henan’s richest person now)—every new artist and toy design under POP MART is carefully researched and strategically evaluated before being signed.

Labubu’s journey before its POP MART partnership had already shown its appeal: Kasing Lung and How2Work had built a small but loyal fanbase pre-2019. But it was through the power of POP MART that Labubu really reached global fame.

Labubu: Most Wanted

Riding the wave of POP MART’s global expansion, Labubu became a breakout success, eventually evolving into a global phenomenon and cultural icon.

Now, celebrities around the world are flaunting their Labubus, further fueling the hype—from K-pop star Lisa Manobal to Thai Princess Sirivannavari and Barbadian singer Rihanna.

In China, one of the most-discussed topics on social media recently is the staggering resale price of the Labubu dolls.

Third edition of the beloved Labubu series titled “Big into energy” (Image via Pop Mart Hong Kong).

“The 99 yuan [$13.75] Labubu blind box is being hyped up to 2,600 yuan [$360]” (#99元Labubu隐藏款被炒至2600元#), Fengmian News recently reported.

Labubu collaborations and limited editions are even more expensive. Some, like the Labubu x Vans edition, originally retailed for 599 yuan ($83) and are now listed for as much as 14,800 yuan ($2,055).

Recently, Taiwanese singer and actor Jiro Wang (汪东城) posted a video venting his frustration over scalpers buying up all the Labubus and reselling them at outrageous prices. “It’s infuriating!” he said. “I can’t even buy one myself!” (#汪东城批Labubu黄牛是恶人#).

One Weibo hashtag asks: “Who is actually buying these expensive Labubus?” (#几千块的Labubu到底谁在买#).

Turns out—many people are.

Not only is Labubu adored and collected by millions, an entire subculture has emerged around the toy. Especially in China, where Labubu was famous before, the monster is now entering a new phase: playful customization. Fans are using the toy as a canvas to tell new stories and deepen their emotional connection, transforming Labubu from a collectible into a DIY project.

Labubu getting braces and net outfits – evolving from collectible to DIY project.

There’s a growing trend of dressing Labubu in designer couture or dynastic costumes (Taobao offers a wide array of outfits), but fans are going further—customizing flower headbands, adorning their dolls with tooth gems, or even giving them orthodontic braces for their famously crooked teeth (#labubu牙套#).

In online communities, some fans have gone as far as creating dedicated generative AI agents for Labubu, allowing others to generate images of the character in various outfits, environments, and scenarios.

Labubu AI by Mewpie.

It’s no longer just the POP MART universe—it’s the Labubu universe now.

“Culturally Odorless”

So, how ‘Chinese’ is Labubu really? Actually, Labubu is not ‘Chinese’ at all—and at the same time, it is very much a product of present-day China.

🌍 Not Chinese at all

Like other famous IP characters, from the Dutch Miffy to Japan’s Pikachu and Hello Kitty, Labubu is “culturally odorless,” a term used to refer to how cultural features of the country of invention are absent from the product itself.

The term was coined by Japanese scholar Koichi Iwabuchi to describe how Japanese media products—particularly in animation—are designed or marketed to minimize identifiable Japanese cultural traits. This erasure of “Japaneseness” helped anime (from Astro Boy to Super Mario and Pokémon) become a globally appealing and commercially successful cultural export, especially in post-WWII America and beyond.

Moreover, by avoiding culturally or nationally specific traits, these creations are placed in a kind of fantasy realm, detached from real-world identities. Somewhat ironically, it is precisely this neutrality that has made Japanese IPs so distinctively recognizable as “Japanese” (Du 2019, 15).

Many Labubu fans probably also don’t see the toy as “Chinese” at all—there are no obvious cultural references in its design. Its style and fantasy feel are arguably closer to Japanese anime than anything tied to Chinese identity.

When a Weibo blogger recently argued that Labubu’s international rise represents a more powerful example of soft power than DeepSeek, one popular reply asked: “But what’s Chinese about it?”

🇨🇳 Actually very Chinese

Yet, Labubu is undeniably a product of today’s China—not necessarily because of Kasing Lung (Hong Kong/Dutch/Belgian) or How2work (Hong Kong), but because of the Beijing-based POP MART.

Wang Ning’s POP MART is a true product of its time, inspired by and aligned with China’s new wave of digital startups. From Bytedance to Xiaohongshu and Bilibili, many of China’s most innovative companies move beyond horizontal product offerings or traditional service goals. Instead, they think vertically and break out of the box—evolving into entire ecosystems of their own. (Fun fact: the entrepreneurs behind these companies were all born in the 1980s, between 1983 and 1989).

In that sense, state media like People’s Daily calling Labubu “a benchmark of China’s pop culture” isn’t off the mark.

Still, some marketing critics argue there’s room for more ‘Chineseness’ in Labubu and POP MART’s brand-building strategies—particularly through collections inspired by Chinese heritage, which could further promote national culture on the global stage (Wang 2023).

Meanwhile, Chinese official channels have already begun positioning Labubu as a cultural ambassador. In the summer of 2024, a life-sized Labubu doll embarked on a four-day tour of Thailand to celebrate the 50th anniversary of China–Thailand diplomatic relations.

The life-sized mascot of a popular Chinese toy character, Labubu, visited Bangkok landmarks and was named “Amazing Thailand Experience Explorer” to boost Chinese tourism. Photo Credit: Facebook/Pop Mart, via TrvelWeekly Asia.

In the future, Labubu, just like Hello Kitty in Japan, is likely to become the face of more campaigns promoting tourism and cross-cultural exchange.

Whatever happens next, it’s undeniable that Labubu stands at the forefront of a breakthrough moment for Chinese designer toys in the global market, and, from that position, serves as a unique ambassador for a new wave of Chinese creative exports that resonate with international audiences.

For now, most Labubu fans, however, don’t care about all of that – they are still on the hunt for the next little monster, and that’s enough to keep the Labubu hype burning.🔥

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References (other sources included in hyperlinks)

• Du, Daisy Yan. 2019. Animated Encounters: Transnational Movements of Chinese Animation, 1940-1970s. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

• Ge, Tongyu. 2024. “The Role of Emotional Value of Goods in Guiding Consumer Behaviour: A Case Study Based on Pop Mart.” Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries. DOI: 10.54254/2753-7048/54/20241623.

• Liu, Enyong. 2025. “Analysis of Marketing Strategies of POP MART,” Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis DOI: 10.54254/2754-1169/149/2024.

• Wang, Zitao. 2023. “A Case Study of POP MART Marketing Strategy.” Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Management Research and Economic Development. DOI: 10.54254/2754-1169/20/

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Guming’s 1 Yuan Ice Water: China’s Coolest Summer Trend

Published

1 month agoon

May 22, 2025

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China this week. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Over the past decade, China’s milk tea industry has become something of a cultural phenomenon. The market has gone well beyond milk tea or bubble tea alone, and is now about any tea-based drink — hot or cold — and the marketing ideas that come with it, from trendy snacks to collectible wannahaves.

This time, it’s the Chinese teashop brand Guming (古茗) that has managed to become an online hit again. Not because of creative collabs or artsy tea cups — the reason is surprisingly plain: selling a cup of ice and water for 1 yuan ($0.15).

How come Guming’s “one cup of iced water” (一杯冰水) has become a hit among Chinese teashop goers? One reason is that it’s something people often want yet hesitate to ask for. Now that it’s actually on the menu (medium cup, regular ice, no sugar), people can just order it for 1 RMB — cheaper than a bottle of water from the supermarket — and it’s become a major hit, like a little ‘luxury’ everyone can afford.

People love getting a cup of ice water (more ice than water) to cool down in hot weather, add it to their lemon tea or iced coffee, or store it in the freezer at home or work for their DIY drinks. Add instant coffee and you’ve got your own iced Americano. Others throw in a tea bag for a refreshing iced tea.

Some say it’s the perfect product for lazy people who don’t make their own ice cubes or who like convenience on the go.

Besides the iced water, Guming has also added a simple lemon water (鲜活柠檬水) to its menu for 2.5 yuan ($0.35). Perfect to quench thirst on a hot summer’s day, one Xiaohongshu user called it Guming’s “secret weapon” (大杀器) in China’s (milk) tea shop market.

Compared to relatively low-priced tea beverage competitors like Mixue Ice Cream & Tea (蜜雪冰城), which sells lemon water for 4 yuan ($0.56), Guming offers great value for money (although it should be noted that Guming, unlike Mixue, doesn’t use real lemon slices but diluted lemon juice).

People are loving these simple and affordable pleasures.

Just last month, Guming shot to the top of Weibo’s trending lists when it launched its new collaboration with the Chinese anime-style game Honkai: Star Rail (崩坏:星穹铁道), featuring a range of collectible tea cups, bags, and other accessories.

Guming was founded in 2010 in Zhejiang and has become one of China’s largest custom beverage chains alongside Mixue and Luckin. Competition is fierce — but at least Guming has its iced water as a secret weapon for this summer.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Jiehun Huazhai (结婚化债): Getting Married to Pay Off Debts

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Lured with “Free Trip”: 8 Taiwanese Tourists Trafficked to Myanmar Scam Centers

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Media12 months ago

China Media12 months agoA Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoThe “City bu City” (City不City) Meme Takes Chinese Internet by Storm

-

China Society9 months ago

China Society9 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media