Chapter Dive

K-Pop’s Recipe for Success: Why Korean Idol Groups Got So Big in China and are Conquering the World

The success of K-Pop in China and beyond is evident – the causes for its success are less obvious.

Published

7 years agoon

K-Pop (Korean pop music) is one of South Korea’s most successful export products today. With bands such as BTS that are dubbed the ‘biggest boy band on the planet’, it is obvious that the locally produced K-Pop has become a globally well-liked phenomenon. Although its popularity is obvious, the reasons why K-Pop became so big, from China to the US and beyond, are less evident.

On coming Saturday, October 13, the South-Korean boy band BTS will perform in an Amsterdam area in front of thousands of fans who have been looking forward to this event for months. Ticket sales for the first concert of the 7-member boy group in the Netherlands were sold out within minutes, despite their relatively high prices, with people paying up to €250 ($290) in the official sales, or even €400 ($460) and more for a single ticket in the unofficial online sales afterward.

It is not just the success of the BTS European tour that is making headlines; the record-breaking views on YouTube on their videos – the latest being the song ‘Idol’, that had more than 200 million views in little over a month – is also attracting the attention of the media.

And BTS is not alone. Other Korean pop (K-Pop) groups such as EXO, BIGBANG, TWICE, Shinee, or Got7, have also broken records when it comes to online video views or Spotify plays.

Although the English-language media attention for the K-pop phenomenon is more recent, the Korean entertainment industry has since long been extremely popular in China and on Chinese social media. In this overview, What’s on Weibo explores the K-Pop popularity (focusing on its idol boy and girl groups), its short history, and success formula.

BTS and More: An Army of Fans

The pop group BTS (방탄소년단), also known as the Bangtan Boys (防弹少年团, lit: ‘Bulletproof Boyscouts’), is an award-winning seven-member South Korean boy band formed by Big Hit Entertainment that debuted in the summer of 2013. They are currently hyped as the “biggest boy band on the planet.”

Initial auditions for the band were held in 2010, followed by roughly three years during which the band was formed and prepared for their major debut, that was promoted on social media months before their actual launch in June of 2013.

The band consists of multi-talented young men. Singer-songwriter Kim Seokjin (Jin) (1992) was studying film at Konkuk University when he was invited to audition by Big Hit; rapper Min Yoongi (Suga) (1993) was an underground rapper before he was signed; dancer and rapper Jung Hoseok (J-Hope) (1994) was part of a dance team in his pre-BTS life.

Lead rapper Kim Namjoon (RM) (aka Rap Monster, 1994) was already active in the music scene as rapper and producer; dancer and vocalist Park Jimin (Jimin) (1995) was a top student as Busan School of Arts before joining; vocalist Kim Taehyung (V) (1995) is known to have one of the most expressing voices of the group; and main vocalist Jeon Jungguk (Jungkook) (1997) was only 12 years old when he auditioned for BTS, followed by three years of intense training.

BTS, formerly ‘Behind The Scenes’, is known for its strong social media presence, which helps to spread its music and connect to its fans, who call themselves an ‘ARMY’ (also stands for Adorable Representative Master of ceremonies for Youth). The band has more than 16 million followers on Twitter, 3.3 million fans on Weibo, 12 million subscribers on Youtube, and nearly 8 million followers on Facebook.

Although BTS is the band that is currently dominating the headlines, there are many more K-Pop bands that are extremely popular on Weibo and beyond. The nine-member South Korean–Chinese boy band EXO, for example, has dozens of fanclubs on Chinese social media. Band member Oh Se-hun alone already has almost 9,5 million fans on his Weibo page. BIGBANG has more than 7 million Weibo fans, the eight-member girl band Girl’s Generation (少女时代) is on the rise with 1,5 million Weibo followers, Super Junior over a million, and the list goes on.

CREATING SUCCESS

A Short History of K-Pop: Finding a Sublime Entertainment Formula

Besides media attention, there has been ample scholarly attention for the Korean pop culture phenomenon over the past decade. The year 2012 especially marked a special moment in the history of K-Pop, when the song ‘Gangnam Style’ by Korean rapper Psy broke all YouTube records and became a global hit.

But before K-Pop became a global force to reckon with – that seemingly rose out of nowhere -, it had already made its first international successes in neighboring countries China and Japan since the early 2000s.

In China, the success of Korean popular culture is defined as Hallyu (韩流)*, the ‘Korean Wave’ since 1997 (Yang 2012, 105). Hallyu encompasses far more than idol bands; it includes the boom of South-Korean dramas, films, celebrity idols, and entertainment programs. In 2002, for example, the South-Korean soap opera ‘Winter Sonata’ became a hit in both China and Japan.

The former Exo (formation has now altered): a Chinese-South Korean band formed by SM Entertainment in 2011, consisting of twelve members separated into two subgroups, EXO-K and EXO-M, performing music in Korean and Mandarin.

The early 2000s mark the ‘first Korean wave’ in China, that mainly revolved around TV dramas produced in South Korea and were liked by females above the age of 30. It was followed by the second wave from the mid-2000s to 2010, when the K-Pop music genre popularized in China.

The third period, after 2010, marks the moment when K-Pop was further incorporated into mainstream Chinese popular culture, with a ubiquity of K-Pop idols in everyday Chinese pop culture, and the launch of Chinese versions of Korean entertainment programs (Ahn 2014, 47). It was also in this ‘third wave’ that you saw the debut of pop groups such as EXO. Formed in 2012, that band incorporates both Korean and Chinese members, performing in both languages.

Although K-Pop from South Korea became somewhat less visible in the PRC during the past few years, mainly because the industry suffered from various politically-motivated bans on Hallyu in China, the genre’s influence on China’s mainstream pop culture is evident, with some Chinese groups, for example, also being modeled after K-Pop bands.

Entertainment Powerhouses

Many studies explain the foreign success of Korean popular culture in Asia, mainly China and Japan, through “cultural proximity,” saying that the success of K-Pop especially occurred in China and Japan because they have, for example, linguistic similarities and corresponding Confucian values (Ahn 2014, 47; Messerlin & Shin 2017, 412).

But the more recent global wave of K-Pop shows that cultural proximity is not the sole answer to the genre’s success. Besides, there is actually nothing traditionally “Korean” about K-Pop, which only emerged in the 1990s (Shin & Kim 2013, 256).

The genre’s success mainly lies in the big players that brought forth the first Korean pop idol groups and have excelled (and still do) in selecting the right entertainment “products” to invest in, with a strong focus on both on the production side and the market demand side.

SM Entertainment, JYP, and YG Entertainment are the first major and leading entertainment houses of the 1990s. Big Hit Entertainment, home to BTS, followed later; founder Bang Si-Hyuk (1972) used to collaborate with JYP Entertainment founder Park Jin-Young (1971) before going his own way in 2005.

-SM Entertainment, founded 1988 by musician and TV host Lee Soo Man (1952)

-YG Entertainment, founded in 1996 by musician Yang Hyun-Suk (1970)

-JYP Entertainment, founded in 1997 by musician and producer Park Jin-Young (1971)

-Big Hit Entertainment, founded in 2005 by producer/songwriter Bang Si-hyuk (1972)

What characterizes these entertainment houses is that they are/were small in terms of revenue and employees (very different from big labels such as Sony or Universal), and play multiple roles as intermediate between musicians and consumers, as well as producers.

Different from many international big players in the entertainment world, K-Pop entertainment companies integrate processes of artist selection, songwriting, management, signing advertisement deals, etc. in-house rather than leaving these processes to various parties outside their own studio (Shin & Kim 2013, 260). Significant about the founders of these entertainment powerhouses is that they all had ample experience in the music industry themselves before starting their studios.

Lee Soo Man, image via AllKpop.com

The story of SM Entertainment, which was founded by musician and TV host Lee Soo Man in 1988, is crucial in understanding the beginning of the K-Pop industry. Lee was inspired by the transforming American music market after spending time there in the 1980s, and decided to replicate US entertainment in a new way. In his first studio he brought together the right equipment, the right expertise, and the right talent all in one place to kick-start his business (Shin & Kim 2013, 263).

Although the first acts that came from SM’s studio were no instant success, Lee was determined in learning through trial and error until he found the right beat and image that struck a chord with young consumers. In doing so, he adopted a strategy in which teenagers were surveyed on what they wanted, and in which he focused on scouting new talent from all over the country to give them intensive training in dancing, singing, and acting at the SM Studio (Shin & Kin 2013, 264).

The band H.O.T. stood at the beginning of the K-Pop genre. (Image by Soompi).

In 1996, eight years after Lee Soo Man started his entertainment company, and going through years of changing, refining, and improving his strategies, the first success was there. The boy band H.O.T., consisting of five hand-picked members who each had their own strength, debuted in 1996 and became the first major success in the short history of K-Pop.

Companies that followed after SM’s initial successes further experimented in adopting new strategies and trying out new styles of music, but stayed true to the idea of in-house training of young, new artists, rather than selecting renowned artists with defined styles (Shin & Kim 2013, 264). With frequently held auditions and training programmes that can last for years, some trainees start as young as 5 or 6 so that they are fully equipped for the entertainment industry by the time they reach adolescence (ibid., 265).

More than being teachers, producers, songwriters, marketers, etc., these entertainment houses are also trend watchers; training their talents in various areas now in order to be able to place them in the right setting and format in the future, corresponding with (global) market demands.

Companies such as SM place an emphasis on the export of music, and focus on appealing to global audiences, making use of hundreds of composers and experts from around the world in doing so. In producing and performing the K-pop girl band Girl’s Generation’s song ‘Genie’, for example, SM Entertainment used a Japanese choreographer, a Norwegian songwriter, and Korean lyricist (Shim 2016, 38).

SHAPING SUCCESS

The Popularisation of K-Pop: A Digital Strategy

Although a main cause of K-Pop’s initial success lies in the (training) strategies adopted by the aforementioned entertainment houses, there are also other major factors that have contributed to its global influence.

The Korean government contributed to the initial success of K-Pop by developing a world-leading internet infrastructure (although the goal of developing that infrastructure, obviously, was not to promote K-Pop), which helped the rapid rise of the genre through online strategies.

According to some studies (e.g. Messerlin & Shin 2017, 422-425), Korean entertainment companies have been the first in the world when it comes to realizing the potential of the internet for the distribution and marketing of their performances; they were already long awake to its possibilities and were acting upon them, while many big players in Europe and America were still focusing on traditional album formats.

What also helped the spread of K-Pop at the time were the relatively friendly and equally balanced Korean policies on issues such as copyright, that were (and are) less protective and restrictive compared to America or the EU (Messerlin & Shin 2017, 421).

The first success (1997-2007) of K-Pop and other Korean popular culture products in China, Japan, and other countries within Asia, have also been called the first major Korean Wave, whereas the current period (2008-present), represents the ‘New Korean Wave,’ that is defined by the role that is played by new media technology and social media as a platform for K-Pop to reach every corner of the world (Jin 2016).

Online strategies were particularly relevant in the context of the (early) K-Pop industry because 1) it was dominated by relatively small businesses that did not have the means to invest in other major publishing platforms than that of efficient online distribution and 2) they did not have costly plants where they could produce CDs, DVDs, or vinyl. Having the high-tech Korean electronical market on their side, online strategies were thus a natural and cost-efficient solution to give publicity to their performances (Messerlin & Shin 2017, 426). More so than focusing on traditional album releases, the release of digital singles that come with visually attractive online videos, for example, is one important K-Pop production characteristic.

Probably the best example showing that this strategy works is the global success of ‘Gangnam Style’ that was made possible through YouTube. By now, six years after its release, the world-famous song by Psy, who was signed by YG Entertainment, has over 3,2 billion plays on YouTube.

The revenue of concert tickets for K-pop performances, its merchandise industry, the digital singles, advertisement income, the many brands wanting to associate themselves with the star industry that K-pop has generated, etc., makes K-Pop production a money-making machine that shows that the model that focuses on traditional (CD) album formats and promotional single releases has become outdated.

CONTINUING SUCCESS

Marketing more than a Band: Active Fans and Interesting Characters

While South-Korea’s innovative music enterprises were crucial for the international launch of K-pop, its worldwide fanbase has now also become a motor driving its continuing success.

Different from the initial spread of K-Pop in China or other Asian countries – where K-Pop has become common in everyday pop culture -, is that many consumers of the genre in the US, Europe, or elsewhere, fully depend on the internet and social media to access K-Pop, as it is not a genre that is prevalent in the mainstream popular culture of their own countries.

The fact that fans of K-Pop in these regions have to actively seek for the latest information and releases of their favorite groups, also means that they have become participatory and engaged consumers in the spread of K-Pop – almost turning them into the ‘soldiers’ of fandoms such as the BTS ‘army’. They have become part of enormous (online) subcultures in various countries across Europe and America.

More than just listening and watching K-pop, these fans become members of the ‘culture’ by translating material, circulating it to friends, or integrating it on their own social media channels (Jin & Yoon 2016, 1285).

TWICE

What further strengthens this fandom is that the successful K-Pop bands are anything but one-dimensional. More than just building on their synced choreography, flawless singing, fashionable looks, and visually attractive videos, the band members of groups such as BTS, EXO, or TWICE, have their own identities, voices, and goals that go beyond music; their various characters and roles within the group resonate with their different fans.

The fact that many K-Pop groups and members also have an androgynous and gender-bender appearance also makes them more interesting to many fans, with many K-pop boys being ‘pretty and cute’ and girls having a ‘strong and handsome’ look, breaking through typical male and female stereotypes.

Amber from F(x) has an androgynous look.

Heechul from boy band Super Junior.

Furthermore, more than pop bands, these K-Pop groups have virtually become ‘platforms’ with their own streaming channels, websites, television shows, merchandise shops, lively online communities, stories, and so on.

In their recent appearance on the US Tonight Show by Jimmy Fallon, BTS frontman RM explained the group’s mission in perfect English, saying: “It is about speaking yourself, instead of letting other people speaking for you. Cause in order to truly know ourselves, it is important to firstly know who I am, where I’m from, what my name is, and what my voice is.”

Many find their voice in K-Pop. And that is a sound, from a local Korean product to a global force, we can expect to grow much louder in the future.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

* For clarity: note that due to scope this article focuses on the development of the K-pop phenomenon, and does not explore the anti-Hallyu or anti-Korean wave movement in China, and the previous bans on Hallyu in the PRC.

References

Ahn, Jungah. 2014. “The New Korean Wave in China: Chinese Uders’ Use of Korean Popular Culture via the Internet.” International Journal of Contents, 10 (3): 47-54.

Jin, Dal Yong. 2016. New Korean Wave: Transnational Culture in the Age of Social Media. University of Illinois.

Jin, Dal Yong, and Kyong Yoon.2016. “The Social Mediascape of Transnational Korean Pop Culture: Hallyu 2.0 as Spreadable Media Practice.” New Media & Society 18 (7): 1277-1292.

Messerlin, Patrick A. and Wonkyu Shin. 2017. “The Success of K-Pop: How Big and Why So Fast?” Asian Journal of Social Science 45: 409-439.

Shim, Doobo. 2016. “Hybridity, Korean Wave, and Asian media.” Routledge Handbook of East Asian Popular Culture,Koichi Iwabuchi, Eva Tsai, Chris Berry (eds), Chapter 3. London: Routledge.

Shin, Solee I. and Lanu Kim. “Organizing K-Pop: Emergence and Market Making of Large Korean Entertainment Houses, 1980-2010.” East Asia 30: 255-272.

Yang, Jonghoe. 2012. “The Korean Wave (Hallyu) in East Asia: A Comparison of Chinese, Japanese, and Taiwanese Audiences Who Watch Korean TV Dramas.” Development and Society, 41 (1): 103-147.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chapter Dive

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

Han Futao’s explosive report on fake patients and systemic abuse has triggered a heated online debate over hospital malpractices, the fragility of the welfare system, and the vital role of investigative reporting.

Published

4 days agoon

February 15, 2026By

Ruixin Zhang

In early February, as China settled into the quiet anticipation of the Chinese New Year, one of the country’s leading investigative journalists, Han Futao (韩福涛), dropped a bombshell report that sent shockwaves of anger across the country.

Han Futao is known for breaking massive scandals. In 2024, he exposed how tank trucks that delivered chemical products also transported cooking oil, without being cleaned. That food safety scandal sparked waves of outrage and prompted a high-level official investigation, leading to criminal charges for those involved.

In his latest explosive report, published by Beijing News (新京报), Han has turned his lens to malpractice in China’s hospital sector. His investigation led him to Xiangyang, in Hubei province, a city with more than twenty psychiatric hospitals, cropping up on every corner “like beef noodle shops” over recent years.

Recruiting Patients

Han found that multiple private psychiatric hospitals lure people in under the guise of free care, promising treatment for little or no cost, along with medication and daily expenses. Some even dispatched staff to rural villages to recruit “patients.”

Troubled by the unusual marketing procedures of these psychiatric hospitals, Han went undercover at several facilities as a caregiver, and sometimes posing as a patient’s family member, only to expose a disturbing reality.

Except for a handful of genuine patients, these hospitals were filled with healthy people who actually received no treatment. Many were elderly citizens swayed by the promise of “free care,” checking in with the hope of finding a free retirement home.

When Han, posing as a patient’s family member, spoke to a hospital manager at Xiangyang Yangyiguang Psychiatric Hospital (襄阳阳一光精神病医院), the director enthusiastically pitched their “free hospitalization” by saying medical fees were completely waived and promising the potential patient a great stay: “Lots of patients stay here for years and don’t even go home for Chinese New Year!”

Meanwhile, the hospitals’ own staff, including caregivers, nurses, and security guards, were also officially registered as patients, complete with admission and hospitalization procedures.

The motive was simple: insurance fraud (骗保 piànbǎo). In China, even after state medical insurance covers part of psychiatric care costs, patients are typically still responsible for a co-pay. These hospitals, both in Xiangyang and in the city of Yichang, exploited the financial vulnerability of those unwilling or unable to pay, using the lure of free accommodation to attract the misinformed. Once admitted, the hospitals used their identities to fabricate medical records and bill the state for non-existent treatments.

According to internal billing records, medication accounted for only a small fraction of patients’ costs. The bulk of the charges came from psychotherapy and behavioral correction therapy, which often leave little material trace and, in these cases, were never actually provided. Many of these hospitals even lacked basic medical equipment and qualified personnel.

Staff were essentially manufacturing invoices, generating around 4,000 yuan (US$580) in fraudulent charges per patient each month, with most funds diverted from the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA).

With each patient yielding thousands of yuan, profitability became a numbers game: the more bodies in beds, the higher the revenue. This perverse incentive gave rise to a specialized workforce of marketers who recruited ordinary people from rural areas, developing sales pitches and establishing referral-based kickback chains, offering bonuses of 400 ($58) to 1,000 yuan ($145) for every new “patient” successfully brought in.

To stay under the radar, hospitals periodically discharged patients on paper to avoid scrutiny from insurance auditors, only to readmit them immediately, or never actually let them leave at all. One story involved a patient who was discharged seven times, each time being readmitted on the same day he was “discharged.”

Day after day, the national medical insurance fund, built on the collective contributions and trust of the entire population, was drained through these calculated deceptions.

From Patients to Prisoners

Han uncovered more. Even more harrowing than the scale of the medical insurance fraud was the condition of those trapped inside. To maximize profit margins, these hospitals slashed costs to the bone. Living conditions were terrible: wards overcrowded, beds crammed side-by-side, and daily activities and food substandard at best.

The hospitals treated their patients more like profit-generating assets than human beings. Patients were subjected to a strict regime: they were forced to follow rigid schedules, restricted to designated zones, and faced physical violence if they did not comply.

During Han’s undercover research, he witnessed the horrific sight of patients being tied to a bed for not following orders, with some patients allegedly being restrained for up to three days and three nights.

Photo by Han Futao, in Beijing News, showing a hall filled with beds at the Yichang Yiling Kangning Psychiatric Hospital, where more than 160 people were housed in just one ward. The lower photo, also by Han Futao, shows elderly “patients” kept in their wheelchairs all day at Xiangyang Hong’an Psychiatric Hospital.

Some patients, despite technically being the ones receiving care, were forced to perform manual labor for the staff. They scrubbed pots, cleaned wards, mopped latrines, and moved supplies. Others even had to take on nursing tasks for fellow patients, such as feeding, bathing, and changing clothes, all in exchange for a few cents to buy a cigarette. Their personal freedom and quality of life were virtually non-existent.

Escape was also difficult. The hospitals had no intention of releasing their cash cows. Rarely was a patient discharged on the scheduled date. To ensure long-term residency, many hospitals confiscated patients’ phones and cut off contact with their families.

Some individuals spent nearly ten years in these prison-like conditions; some even died there. Meanwhile, those truly suffering from mental illness received no real treatment, often seeing their condition worsen or developing deep-seated trauma toward psychiatric care.

Fragile Public Trust in Welfare-Related Institutions

In China, there is a common belief that if you spot one cockroach in the room, there are already a hundred more hiding. As the story has gone viral over the past two weeks, netizens pointed out that Xiangyang and Yichang were likely not the only cities using such predatory tactics to cannibalize the national treasury. Han’s investigation struck a deeper nerve, and public anxiety over the security of social insurance once again bubbled to the surface.

China’s national health insurance is a cornerstone of the broader social insurance system and a vital part of life for nearly every citizen. It is generally divided into two categories: Employee Medical Insurance and Resident Medical Insurance. Employers are legally, at least in theory, required to contribute to the employee scheme, typically 6% to 9% of a worker’s salary. Non-employees, such as farmers, students, and freelancers, usually pay for Resident Insurance out of pocket, currently costing around 400 yuan ($58) annually. Under the employee scheme, inpatient reimbursement rates are roughly 80% to 85%; after approximately 25 years of contributions, members enjoy lifelong coverage without further payments. The Resident Insurance, however, offers significantly lower protection.

This system was designed as a fundamental safety net to alleviate the fear of falling into poverty due to illness or being left destitute in old age. For young Chinese job seekers, whether a company pays into social security used to be a non-negotiable criterion. However, as scandals shaking the foundation of this system have become more frequent, the mindset of the youth is shifting: Is it even worth paying into anymore?

Recent years have seen a steady stream of corruption scandals involving the embezzlement of social security funds.

Despite the authorities’ firm stance and high-profile punishments, 2025 was still marked by reports of officials — including the insurance bureau’s finance head — misappropriating funds to play the stock market. A June 2025 report even alleged that 40.6 billion yuan (US$5.8 billion) in national pension funds had been misappropriated or embezzled by local governments.

In one surreal case from Shanxi, a CDC employee’s records were doctored 14 times to create an absurd history of “starting work at age 1 and retiring at 22,” allowing them to pocket 690,000 yuan ($100,000) in pension while still drawing a salary at a new job.

These stories exposing large-scale abuse of the medical insurance system, combined with the extension of the minimum contribution period for retirement from 15 to 20 years amid a slowing job market and a gradually rising retirement age, are leading netizens to question the necessity of paying into the system. This is reflected in comments such as:

-“First it was 20 years, then 25, then 30. They move the goalposts whenever they want, but the benefits never improve.”

-“I won’t buy anything beyond the bare minimum resident insurance; who knows if there will even be a payout in the future?”

-“With a deficit this large, whether we’ll ever see that money is a huge question mark.”

-“I’m not even sure I’ll live to see 65 anyway.”

Echoes of the Cuckoo’s Nest

In response to Han’s latest exposure, local authorities immediately launched investigations, and state-run media outlets issued sharp criticism. By now, fourteen hospital executives have been criminally detained on suspicion of fraud.

Although the official report, published on the night of February 13, acknowledged that there was widespread medical fraud, with patients remaining hospitalized after recovery or empty beds being registered without any patients there, it said no evidence was found that people without mental disorders were admitted, which was one major finding of Han’s undercover operation.

This led to new questions, because how could fraud, abuse, fake discharges, and official corruption be acknowledged while denying the central allegation: that healthy people were being locked up? And how could people prove they were not mentally ill, while being a patient inside a psychiatric hospital?

Political & social commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) wrote on Weibo that, while he applauded Han and his team for exposing the mismanagement at psychiatric hospitals in Hubei, he also saw the report’s conclusions about the patients as a reminder that journalists should exercise caution when making accusations. Some sarcastic commenters suggested that perhaps Han had not sacrificed enough and should have admitted himself as a patient instead.

And so, in a way, the debate has now slowly also shifted – from the initial shock over Han’s report, to the anger and distrust surrounding state institutions and social security abuse, to the role of investigative journalism in China today. “He’s a hero,” some commenters said about Han.

In the end, the entire story is so absurd that some commentators have drawn parallels to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (飞越疯人院), where Randle P. McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) fakes insanity to serve his sentence in a mental hospital instead of a prison work farm, only to find out that the endless chain of control and abuse at the psych ward is much more brutal than a prison cell.

The question inescapably becomes who the sane ones actually are.

Meanwhile, the scandal shows that public anxiety about the future and distrust of state institutions tend to rise quickly and deepen slowly with each new controversy. As trust in the national welfare system appears fragile, one sentiment persists: that there is far more to uncover, and that there are far too few Han Futaos to do it.

By Ruixin Zhang

With additional reporting by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Chapter Dive

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

We’re at a very complicated time in our online lives. An explainer of “Chinamaxxing,” the “kill line,” and the platform politics behind them.

Published

2 weeks agoon

February 3, 2026

While American TikTok users find themselves in a “very Chinese time” of their lives, Chinese netizens are fixated on the American “kill line.” Beyond the apparent digital divide, both trends reflect shared anxieties and shifting power dynamics between the US and China.

In the first month of 2026, two noteworthy social-media trends, both telling of the times we live in, went viral in the US and China: a China-focused trend in the US and an America-focused one in China.

In the US, TikTok videos and Instagram posts showing young people cheerfully portraying themselves as “Chinamaxxing,” or being “in a very Chinese time” of their lives, began popping up across social media.

Meanwhile, in China, posts about the darker side of American society and its so-called “kill line” (斩杀线) dominated trending lists.

In this week’s chapter dive, I’ll explain the stories behind both of these trends and why, despite their very different implications, the dynamics driving them are strikingly similar.

Converting to “Chinese Baddies”

Over the past week, the phrase “Becoming Chinese” (成为中国人 chéngwéi Zhōngguórén) has been gaining traction on Chinese social media. On January 30, the headline “Why ‘Becoming Chinese’ Videos Are Going Viral’ even made it to the number one most popular topic on Chinese platform Toutiao (“成为中国人视频为什么火了”).

Before reaching China’s social media, the trend had been gaining momentum on TikTok and Instagram for months, with viral videos showing foreigners humorously flaunting their supposedly deep connection to China by doing things like drinking a nice cup of hot water (the solution to everything), using traditional Chinese medicine, sitting in a squatting position while smoking Chinese cigarettes and holding Tsingtao beer, eating noodles or dim sum—all while wearing that popular Adidas “Chinese jacket.”

This is all referred to as “Chinamaxxing” or “Chinesemaxxing”: optimizing life by living in a Chinese-coded way.

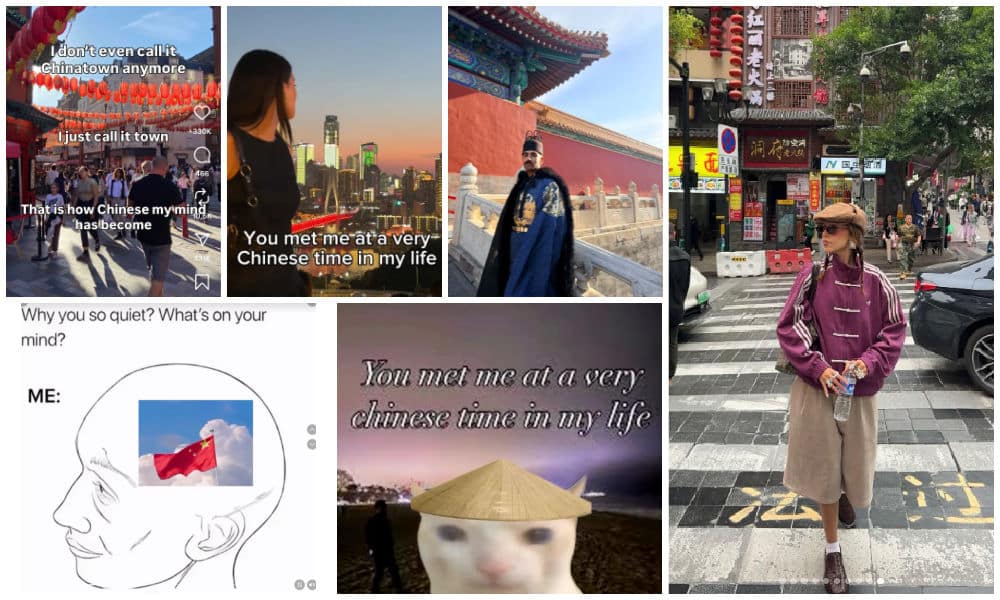

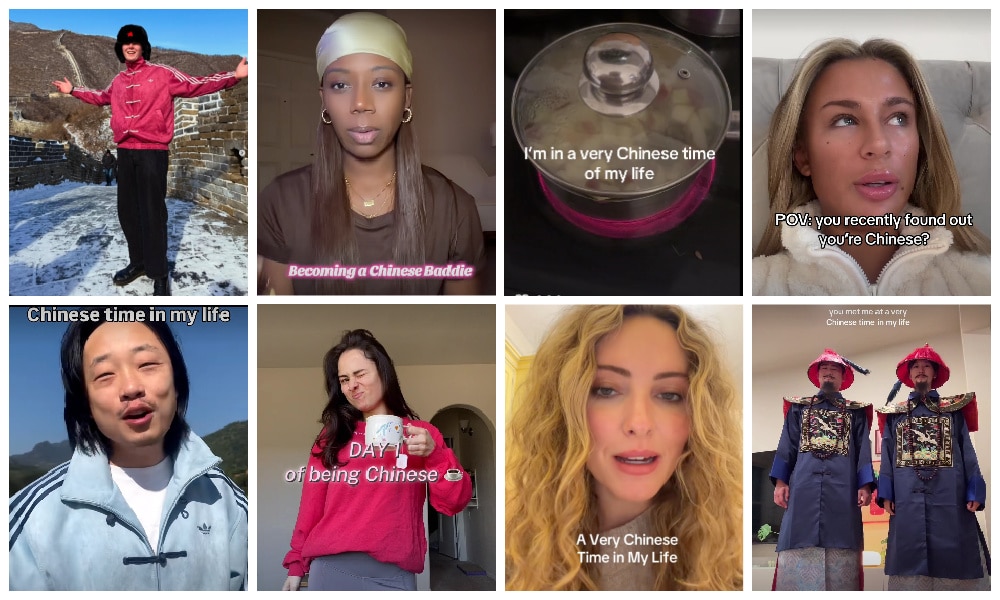

Various “very Chinese time” examples (TikTok/Instagram).

The build-up to this moment has actually been underway for several years. In the post-Covid era, China’s global pop culture influence has grown noticeably, driven both by increasingly outward-facing efforts from Chinese companies and state actors, and by a broader shift among younger audiences in the US toward Asia.

As part of this broader shift, several notable online moments have emerged over the past few years, including the viral success of a Chinese pop song in 2022; the 2024 breakout of Black Myth: Wukong; the 2025 “TikTok refugee” phenomenon; Chinese rapper SKAI ISYOURGOD becoming a staple on TikTok; and the widely watched March 2025 China tour of American YouTuber IShowSpeed, followed by a less impactful but still meaningful China visit by American influencer Hasan Piker.

The now-famous line “You met me at a very Chinese time in my life”—inspired by the quote “You met me at a very strange time in my life” from the final scene of Fight Club—first surfaced on X in April 2025. The X account “Perfect Angel” (@girl__virus) then posted the phrase in a tweet that since has gathered over 950,000 views.1

The X post of April 5, screenshotted Jan 30, 2026.

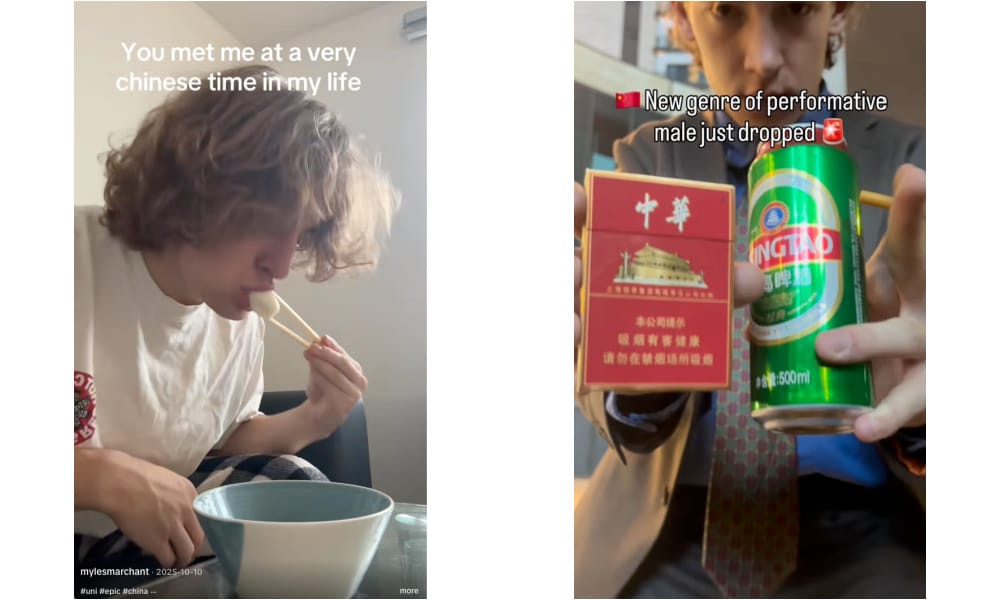

The trend snowballed from there, especially in October 2025. When creator Myles Marchant posted a video of himself eating dumplings while using the phrase, it received nearly 200k likes. Afterward, all kinds of internet users, but particularly American content creators, started using the phrase in videos to show off just how “Chinese” they were.

Myles Marchant and McMungo in their videos.

As the meme went viral, from October 2025 through January 2026, it continued to evolve. What began with cigarette smoking and playful performances of “Chinese” behavior has, for many TikTok users, grown into something more. Drawing on Chinese food philosophies and wellness practices, they now present “Becoming Chinese” as a lifestyle trend focused on better energy, health, and skincare.

Chinamaxxing, Chinese Baddies, Becoming Chinese, A Very Chinese Time of My Life: Trends on Tiktok.

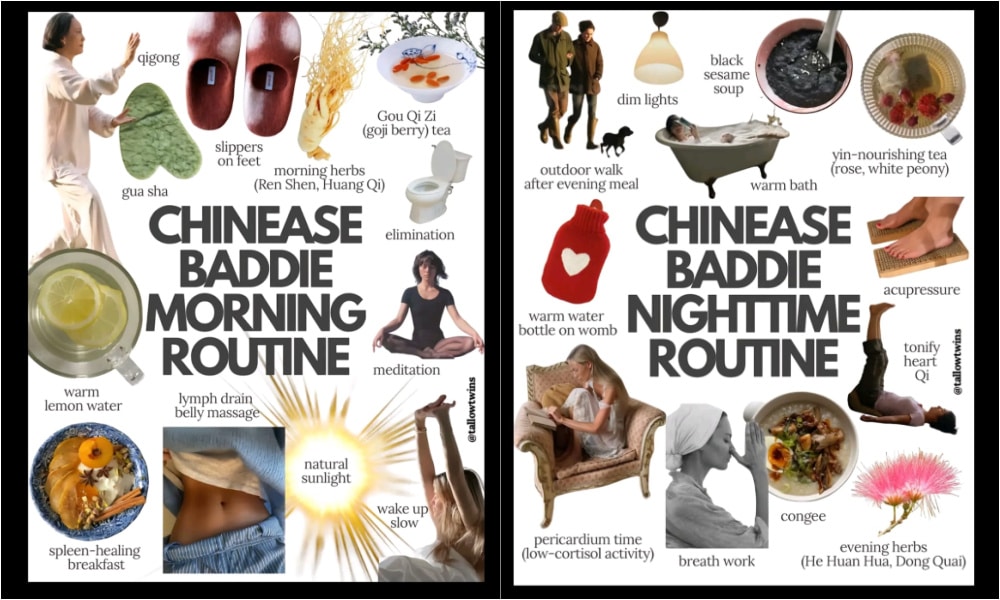

TikTok creator Missmazz, for example, introduced her morning routine “since recently converting to Chinese”: wearing slippers in the house, doing small jumps to “activate” lymph nodes, and drinking warm water and herbal tea. Creator Ohplsnatagain also shared her “first day of being Chinese,” drinking ginger tea, boiling apples, wearing red, and avoiding cold drinks.

“Chinease” morning and night routines, shared on TikTok by Tallow Twins.

Besides those aspiring to become Chinese, some Chinese creators have expressed their joy about the trend others emerged as online guides to these newly adopted identities and lifestyles. Creators like Emma Peng made a video telling people, “my culture can be your culture,” while others, like Sherry, actively encourage people to become Chinese: “It’s gonna be so fun!”

They have now formed an online community of self-labeled “Chinese baddies,” sharing recipes, morning routines, and tips for being as ‘Chinese’ as possible. On Chinese social media, netizens are humored by the overseas trend, and see it as a sign of just how powerful Chinese cultural confidence has become (“藏在烟火气里的文化自信才最有感染力”).

America’s “Kill Line”

While American social media users have been busy Chinamaxxing, Chinese social media have been feverishly discussing America’s so-called “kill line” (also translated as “execution line,” 斩杀 zhǎnshāxiàn).

The term first went trending in late 2025 after it was coined by the Northern Chinese livestreamer Squishy King (斯奎奇大王), better known by his nickname “Lao-A” (牢A), who is particularly active on Bilibili, the Chinese platform known for its strong anime and gaming subculture.

Lao-A has been livestreaming since 2024 without ever showing his face on camera. Through pure voice narration over images, he became known for casually chatting in livestreams—sometimes lasting over five hours—about a wide range of topics, especially those connected to American society. Lao-A claimed he was a Chinese biomedical student in Seattle who worked part-time as a forensic assistant, handling unclaimed bodies and preparing them for medical education or research.

Profile image of “Lao A”, who never shows his face on streams.

On November 1, 2025, during a stormy Halloween Friday night, Lao-A hosted another one of his five-plus-hour live-chatting streams, in which he spoke about the bad weather and homelessness in the US.

He mentioned how people living on the streets could easily die from a cold or Covid that turns into pneumonia without proper treatment, and how dreadful he felt about the freezing conditions—knowing that on Monday he would see the bodies of people who had died on the streets that very weekend.

According to Lao-A, the unidentified bodies of homeless people would be brought by the police to his school, where they could still generate some value. Drawing comparisons to “harvesting in harsh winter,” he introduced the concept of the “kill line,” borrowing the term from multiplayer/role-playing games such as Hades or League of Legends.

In gaming, a “kill line” refers to the health-point (HP) threshold below which a character can be instantly killed, with no possibility of recovery. Lao-A suggested that the situation of marginalized and homeless people during Seattle’s winter was similarly bleak: their deaths are treated as almost inevitable, even though basic medical care—such as antibiotics—might prevent them.

The way Lao-A spoke about his work and the darker sides of American society spread rapidly through Bilibili’s comment culture and then into wider Chinese social media, especially as he expanded on the topic in other livestreams, where he further discussed poverty in America, from the healthcare system to food assistance programs.

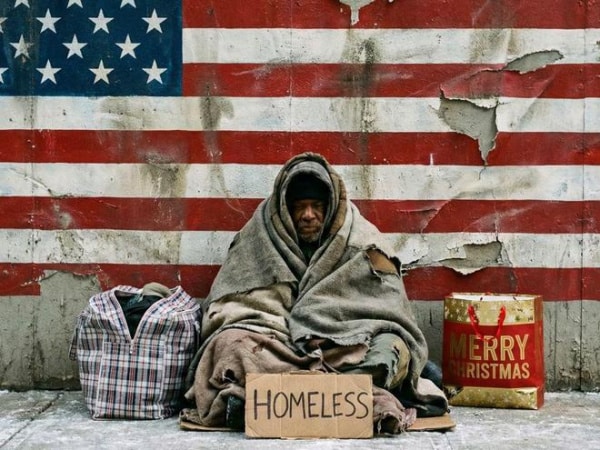

Visuals accompanying a report about Lao-A on the 163.com website.

Lao-A particularly focused on medical bills as a key component of America’s “kill line.” He described how people suffer first and then seek care, only to be further burdened by crushing costs—arguing that the American system drains people at their most vulnerable. An unexpected event such as illness, job loss, or a car breakdown can suddenly disrupt a family’s cash flow, leading to unpaid bills and a collapse in credit scores. Bad credit, in turn, makes it harder to rent housing, pass background checks, or secure affordable insurance, while debts pile up. This downward spiral, he suggested, eventually pushes people past a final execution threshold: too broke, too sick, too depressed, and too far gone to recover, ending in homelessness or addiction and shortening life spans.

Lao-A framed this as a systemic trap created by capitalism: a game mechanic in which the rules are rigged so that once someone falls below the threshold, the system itself kills them. Besides the “kill line,” he introduced other gaming-inspired terms, such as using “Gundam” (高达, after the Japanese model kits) to refer to the bodies he handled, or “slimes” (史莱姆) for decomposed bodies found in sewers.

In some ways, Lao-A’s “kill line” resembles the concept of ALICE (“Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed”), a demographic category created by the nonprofit United For ALICE to describe American households that earn above the federal poverty line but still cannot afford basic necessities such as housing, childcare, healthcare, or groceries.

By mid-December 2025, the term and the stories surrounding it had entered the mainstream and began hitting trending lists on Weibo, Toutiao, and Kuaishou.

Cartoon by Chinese state media outlet CRI Online about the killing line. Top texts say: “Thriving economy, America first, America great again.” On the staircase, it says: “Unemployment, unexpected costs, illness.”

As the “kill line” quickly entered China’s online lexicon, it was also embraced and boosted by official media. After earlier coverage, Qiushi (qstheory), the Chinese Communist Party’s most authoritative theoretical journal, published a January 4 commentary arguing that the “kill line” reflects a widespread condition in which Americans’ capacity to withstand risk has been pushed to its limits, while Trump’s MAGA movement fails to work towards a solution as it focuses on cultural identity rather than addressing the economic challenges faced by millions of Americans.

Something that also caused a stir online, is how American media began reporting on the Chinese “kill line” concept. First Newsweek on December 26, followed by The Economist and later The New York Times. The phrase even surfaced at the World Economic Forum in Davos, when a Chinese state-media reporter asked US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent about the phenomenon.

All of this placed a considerable spotlight on Lao-A himself, whose real identity and personal backstory began to be questioned by internet users. After he was identified as the possibly 30-year-old “Alex Kong 孔” from Daqing, who attended a community college in Seattle, more of his details were leaked online. Lao-A said he feared for his safety and returned to China.

This supposed “escape from America” became a major story on Chinese social media, with Lao-A repeatedly topping trending charts from January 17 onward. Attention peaked around January 22–23, after he joined Weibo and participated in joint livestreams with Chinese professor and prominent nationalist commentator Shen Yi (沈逸), and again around February 1, when he streamed with foreign-policy commentator Gao Zhikai (高志凯). During this period, Lao-A and the dystopian “kill line” narrative completely dominated Chinese online discussions.

Throughout his solo livestreams and collaborative appearances, Lao-A has continued to paint an especially dark picture of American society, describing graphic gang violence, failures in the education system, murky organ-transplant systems and black markets for organ harvesting (claiming that healthy Chinese students who have not used drugs are “very valuable”), and Chinese female students abroad as “ideal hunting targets” for white men—explicitly warning Chinese parents not to send their daughters to study overseas.

By now, “kill line” is a term that pops up all over Chinese social media and is applied to all kinds of news coming from America, from the Epstein files to the Alex Pretti shooting.

Where the “Kill Line” Meets “Chinamaxxing”

On the famous Know your Meme website, the phrase “You Met Me At A Very Chinese Time In My Life” is described as “ultimately meaningless and purposefully absurd.” But it’s actually not.

Both the “Becoming Chinese” trend and the discourse surrounding the “kill line” are shaped by our current media moment and reflect broader, shifting narratives about China, the United States, and global power.

While China’s rise has been a major media theme for years, a lot of Chinese influence had felt invisible for younger generations in the West, even if they were already living, wearing, and consuming “made in China.” More recently, however, China’s soft power narratives have become more visible, with popular culture emerging as a powerful tool.

The changing attitudes toward “made in China,” alongside a growing interest in Chinese tradition and elements of ancient culture, took shape in the late 2010s as China’s domestic cultural confidence increased. This development was partly supported by China’s flourishing livestreaming economy & homegrown e-commerce platforms, as well as more assertive official messaging around the idea of products being “proudly made in China.”

Wang Yibo poses with Anta’s “China” t-shirt in 2021, the year that “made in China” had become cool again.

Younger Chinese consumers in particular—those born after 1995 or 2000—began showing more interest in domestic brands than earlier generations. This trend reflected not just consumer preference, but a stronger identification with Chinese culture and national identity. By 2021, a Global Times survey indicated that most Chinese consumers believed Western brands could be replaced by Chinese ones (75% of respondents agreed that “national products could fully or partially replace Western products“).

By 2025, pop-culture products emerging from this renewed focus on domestically produced goods—often incorporating traditional Chinese aesthetics—began reaching audiences beyond China, finding traction in Western markets as well.

At the same time, the United States experienced significant societal divisions in the aftermath of the 2024 elections, while its global image and cultural influence were affected by the dismantling of traditional US soft power channels.

Together, these developments shaped broader changes in global public opinion, tilting toward a more favorable view of China as “the world’s leading power,” and fueling conversations about a future increasingly framed through a Chinese lens.

This wider geopolitical context forms the backdrop against which the two viral trends discussed here took shape.

–Why these trends took off

🔹 The Decay of the American Dream and Insecurities about China’s Dream

Geopolitical power shifts alone are not enough to explain the virality of both “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” discourse. Current socio-cultural dynamics also play a major role.

In both the US and China, people’s sense of security, future, and identity is shifting, and other countries are increasingly used as mirrors, escape routes, or coping mechanisms to process that change. Young working-class Americans under Trump and middle-class Chinese facing “involution” (nèijuǎn 内卷, a seemingly never-ending societal rat race) are questioning their systems, but arrive at opposite conclusions by using each other as contrasts.

🇺🇸 “A projection of what Americans believe their own country has lost”

In a recent article for Wired,”Why Everyone Is Suddenly in a ‘Very Chinese Time’ in Their Lives,” the authors argue that the “very Chinese time” meme is “not really about China or actual Chinese people,” but instead functions as a projection of what Americans believe their own country has lost.2

Rather than offering an accurate depiction of China, the trend relies on stereotyped markers of “Chineseness” to express frustration with US infrastructure erosion, political instability, polarization and, as PhD researcher Tianyu Fang puts it, “the decay of the American dream.”

In this context, China appears as an aspirational contrast—”less as a real place than an abstraction”—through which Americans critique their own realities.

🇨🇳 “Why China is suddenly obsessed with American poverty”

Similarly, in a The New York Times article titled “Why China Is Suddenly Obsessed With American Poverty,” author Li Yuan argues that the “kill line” narrative offers emotional relief to Chinese netizens while also helping to deflect criticism of domestic leadership. As she writes, “the worse things look across the Pacific (…), the more tolerable present struggles become.”3

A related conclusion is reached in an article by The Economist,4 which suggests that the surge in discussion about America’s failures says less about the realities of life in the US than about China’s own anxieties over slowing growth and the fragility of domestic political discourse.

While the “Chinese Dream,” which prioritizes collective effort and national strength, is promoted as part of state ideology, everyday life tells a more sobering story, in which climbing the social ladder seems increasingly out of reach for millions of Chinese facing economic slowdown, high youth unemployment, and a constrained space for criticism.5

Yet as narratives about the perceived failure of the “American Dream” flood Chinese social media, China itself begins to look like the better place—even with all of its own challenges.

Ultimately, both the “Becoming Chinese” and “kill line” phenomena are embedded in collective anxieties about vulnerability and decline, fueling a growing hunger for counter-narratives.

–The stories told

🔹Fantasizing about “the Other”

Those counter-narratives do not need to be realistic. To fulfill their role in channeling perspectives, insecurities, and even a sense of cathartic relief about the present and future, they can’t actually be nuanced. Simplification, exaggeration, and symbolic contrast are precisely what make them effective.

🇺🇸 “Chinese cultural identity as a disposable trend”

In the case of “Becoming Chinese,” the trend is comically fairy-tale–like, suggesting that people of all backgrounds can “turn Chinese” in the blink of an eye. One popular meme even implies that there is no need to “kiss the frog” to meet the prince: simply looking at the frog would already make you Chinese.

Beyond fairy tales, there is also a gaming logic at play in other “Becoming Chinese” memes, with different levels of “Chineseness” to unlock to reach that final mythical state of Being Chinese.

Although this is all tongue-in-cheek, it is also what has made the trend a focal point of criticism recently. Chinese cultural identity is turned into a game, a disposable trend for non-Chinese users. Some Chinese and Chinese-American creators have taken offense at how casually Chinese identity is treated—particularly after being a target of discrimination during the Covid era, only to now become a source of social-media hype.

Others argue that it feels more like appropriation than appreciation, suggesting that “Becoming Chinese” reflects a form of Orientalism: a simplified fantasy of an “exotic” China that mirrors Western desires, anxieties, and power relations rather than the lived realities of Chinese people.

Similar critiques have surfaced on Weibo, especially targeting Chinese-American social-media users. Some commenters accused them of seeking Western validation, framing their participation in the trend as an expression of unresolved insecurities about their own identity.

When confronted with such criticisms, some TikTok users respond defensively. One critical creator shot back at the “dumb comments” in his feed, saying: “Forget meeting you at a very Chinese time in your life—when am I going to meet you at a very intellectual time in your life?”

🇨🇳 “American society as a dystopian game”

The success of Lao-A’s descriptions of America’s dark sides and its “kill line” also lies in how he gamifies social stratification and marginalization. He does not just borrow terms from gaming, but frames society itself as a dystopian game, where reaching certain thresholds means it is simply game over.

While the “kill line” concept has been embraced by netizens and official media alike, the persona of Lao-A has grown increasingly controversial. As criticism mounted over inconsistencies and falsehoods in his stories about America, including his education and alleged “escape,” netizens began questioning how much was factual and how much was Hollywood-inspired: from slimy corpses in Seattle sewers to thriving black markets for organs, cannibalism or gangs beheading victims and hanging their skinned heads like “candied apples” (糖霜苹果).

In a recent livestream, Lao-A finally admitted that around “40 percent” of what he had told was not based on his own experience, with part drawn from borrowed accounts and part outright fabricated.

In a way, the popularization of Lao-A’s stories about the US resembles the wave of reporting about China’s “social credit score” in Western media between 2018 and 2020, when even reputable outlets claimed that the Chinese government was assigning all of its 1.4 billion citizens a personal score based on their behavior, linked to what they buy, watch, and say online. In many ways, those stories fed into Western fears about AI, privacy, and these developments becoming reality in Western societies themselves.

There was some truth in reports about the nascent social credit system in China, but much of the coverage was exaggerated or simply false—much like Lao-A’s stories, which mix real structural problems with a heavy dramatization and elements of fiction. In the end, that distinction matters less than you might expect. Lao-A has by now almost become a myth himself, praised by many not for the falsehoods he spread, but for consolidating a strong image of a dystopian America, one that balances the dark portrayal of China so often encountered in US media.

–Dynamics behind the trends

🔹Platform Politics

Both “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” are not just products of broader geopolitical shifts, US–China relations, and growing social insecurities. They are also inherently shaped by the platforms they emerged from and, in many ways, are products of those platforms themselves.

🇺🇸 “Chinese baddies building their TikTok success on Chinamaxxing”

In the West, “Becoming Chinese” trends are primarily created and shared on TikTok, an entertainment-focused platform built around endlessly scrolling short-form videos that are algorithmically recommended based on user behavior (particularly what people watch, engage with, or quickly scroll past). Although TikTok is originally Chinese—its parent company is ByteDance—it is separated from the app’s Chinese version (Douyin) and is only used outside China. TikTok has been popular in the US ever since its 2017 launch and is now used by some 200 million people there, with daily life, comedy, fashion & beauty and pop culture being among some of the popular content categories.

Since 2020, there have been repeated discussions about banning TikTok in the US over concerns about national security and the power of its algorithm due to its Chinese ownership—a prospect that proved widely unpopular among American TikTok creators. (As of this month, TikTok has finally reached a deal that allows the app to continue operating in the US, with its algorithm trained only on US data.)

As a result of this resistance against a potential ban, and against any policies changing the app’s dynamics, large numbers of users previously “fled” to the Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu, and began expressing overtly pro-China sentiments as a playful form of protest against what they saw as the anti-Chinese undertones of the proposed ban.

This background, along with the fact that TikTok is a platform generally focused on humor and relatability, has made it a place that is rather positive when it comes to China-related content. Earlier research confirms that, in sharp contrast to traditional US media, popular content on the app tends to frame China in a largely non-political and positive way.6

This has led to the current dynamics of the “Becoming Chinese” trend as a way for creators to profit. By creating these positive, entertaining, and short videos, they can aim for likes, build community, and grow their accounts. For a few “Chinese baddies,” their entire success was built on “Chinamaxxing.”

🇨🇳 “How to score on Bilibili”

In China’s social media environment, stories about the darker side of American society have always been a consistent part of online circles discussing US–China relations, and this holds especially true for Bilibili.

Although Bilibili originally started as a platform focused on ACG (anime, cartoons, games), it has evolved over the years along with its user base, which consists largely of college students and young professionals. It is now home to many creators producing political and geopolitical analytical content in a way that encourages interaction and aligns with Bilibili’s rather unpolished, humorous style.

Different from TikTok in America, popular Western-related content on China’s Bilibili platform is often framed through a strongly pro-Chinese lens and frequently carries anti-Western narratives. There are also foreign creators on the platform whose credibility is boosted when they produce what is considered pro-China or party-conforming content.7

Lao-A succeeded on Bilibili precisely because he tapped into what its users are most drawn to: using gaming slang and imagery to cast a dark light on American society on a platform whose users are increasingly politically engaged. At the same time, he claimed to be located in America itself, deep within the grim reality he described—further boosting his credibility.

In doing so, Lao-A showed that he understands how to “score” on Bilibili and has ultimately made an irreversible impact. The fact that he fabricated some of his stories does not seem to bother many people, who claim that being more nuanced would have simply led viewers to swipe away. These tactics have helped make him one of the most prominent “America watchers” on China’s social media in 2026.

🌀 Utopian Borrowing and Dystopian Pointing

Put side by side, “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” appear to be opposites: one romanticizes China, the other condemns America; one is playful and humorous, the other dark and serious; one thrives on Western social media, the other emerged from Chinese platforms; one is entertainment-driven, the other overtly political.

Yet both are built on similar foundations. Each taps into underlying anxieties and frustrations about the present, responds to broader global shifts, and relies on gamified language, stereotypes, or selective details that easily resonate with online audiences and encourage them to engage. In doing so, both trends are perfectly adapted to the platform dynamics and social media environments in which they flourish, and from which they benefit.

What these trends ultimately reveal is not a definitive truth about either country, but the power of digital discourse to seize on existing discontent to shape or influence perceptions of the United States and China. One becomes a utopia to borrow from, the other a dystopia to point at. Perhaps the most important takeaway is not how different these trends are, but how similar the underlying impulses behind these narratives actually are, revealing deeper ideas about American and Chinese internet users having so much more in common than meets the eye.

Meanwhile, Lao-A has already begun to move on a bit. His focus for now has shifted, at least partly, from America’s “kill line” to Japanese society. On TikTok, many of the creators who “discovered” they were “Chinese” in early January have also pivoted and are now posting about Pilates, reviewing Thai food, or booking holidays to Spain. Even “Perfect Angel,” who was the first to tweet that “Very Chinese time” phrase in 2025, just tweeted that “being Canadian is in this year.”

Who knows what we’ll become tomorrow? Maybe it really is time for that cup of hot water now.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 See: Elle Jones. 2026. “Why Everyone Is Now Chinese.” Substack, January 11. https://substack.com/home/post/p-184141480 [January 30, 2026].

2 See: Zeyi Yang and Louise Matsakis. 2026. “Why Everyone Is Suddenly in a ‘Very Chinese Time’ in Their Lives.” WIRED, January 16 https://www.wired.com/story/made-in-china-chinese-time-of-my-life/ [January 30, 2026].

3 See: Li Yuan. 2026. “Why China Is Suddenly Obsessed With American Poverty.” The New York Times, January 13 https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/13/business/china-american-poverty.html [February 1, 2026].

4 See: The Economist. 2026. “China Obsesses over America’s “Kill Line.”” The Economist, January 12 https://www.economist.com/china/2026/01/12/china-obsesses-over-americas-kill-line [February 1, 2026].

5 See: Ma Junjie. 2025. “A ‘Loser’s Nation’ and the Abandoned Chinese Dream.” The Diplomat, September 4. https://thediplomat.com/2025/09/a-losers-nation-and-the-abandoned-chinese-dream/ [February 3, 2026].

6 See: Cole Henry Highhouse. 2022. “China Content on TikTok: The Influence of Social Media Videos on National Image.” Online Media and Global Communication 1 (4): 697–722.

6 See: Florian Schneider. 2021. “China’s Viral Villages: Digital Nationalism and the COVID-19 Crisis on Online Video-Sharing Platform Bilibili.” Communication And The Public 6 (1-4): 48-66.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West