China Arts & Entertainment

The Early Days of Rock in China – Interview with Sinologist & Hardrocker Jeroen den Hengst

From copied tapes to a unique rock scene – Jeroen den Hengst was part of the Beijing rock scene when it first awakened.

Published

9 years agoon

Dutch Sinologist and musician Jeroen den Hengst was part of the Beijing rock scene when it awakened in the late 1980s. Nearly three decades later, Den Hengst looks back on the early days of rock in China – before, during and after the Tiananmen protests – and talks about the music scene in Beijing and his personal path from young Sinologist to serious hardrocker.

When I notice some glitters sparkling on Den Hengst’s face as I meet him in downtown Amsterdam in early Spring, he nonchalantly brushes them off. He was performing the night before, he tells me.

Den Hengst is the host and guitar player of Amsterdam’s Hardrock Karaoke, which has become quite a phenomenon in Amsterdam and beyond. We sit down, order a beer and talk about Den Hengst’s musical journey that started in the early days of China rock.

FIRST STEPS ON THE MAINLAND

“There was simply no access to pop music. I had brought forty cassette tapes with music to China; they were copied hundreds of times.”

“I arrived in China in September 1987 when the famous Beijing musician Cui Jian (崔健) was just getting big. I came to China to study at Peking University as part of my Sinology studies at Leiden University, but soon ended up more in the Beijing music scene than I was in class,” Den Hengst tells:

“I never used to be a really good student – music was always my true passion. I had also played in bands throughout high school. But I was very interested in China. I had to learn its history for my final high school exams. The language intrigued me. So I started studying it at university and had already finished my third year when I arrived in Beijing. I soon discovered I couldn’t even properly order food, despite studying the language. It was my first time in China.”

“Singer Cui Jian got together at the time with Eddy [Randriamampionona] from Madagascar and drummer Zhang [Yongguang]. They would perform in Ritan Park with their band Ado. I would go there, and found out that there were quite some young people making music.”

THE ADO BAND IN 1989 WITH FROM LEFT TO RIGHT SANR (DRUMS), EDDIE FROM MADAGASCAR (GUITAR), BALASZ FROM HUNGARY (BASS), LIU YUANR (SAX) AND FRONTMAN CUI JIAN (IMAGE FROM REDIANWANG)

“Zang Tianshuo (臧天朔) would also play there, and I became acquainted with Chinese rock musician He Yong (何勇), who later became well-known with his album Garbage Dump (垃圾场). I knew all of them, it was just a small bunch of people in that scene. Especially the foreigners in Beijing knew each other at the time – there were not that many, and if there was something happening we just knew it through word of mouth.”

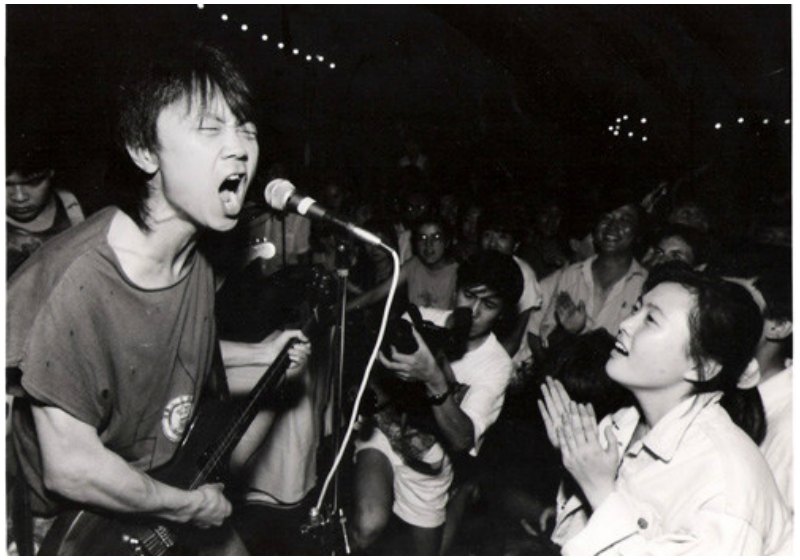

Singer He Yong in early 1990s (Xinhua).

Singer He Yong in early 1990s (Xinhua).

“I started frequenting these sort of performances and would join on stage every now and then, as I did with the band Mayday (五月天), in which He Yong also played. They had all just started playing and had zero background knowledge in pop music as there was simply no access to that kind of music. I had brought forty cassette tapes with me to China; they were copied hundreds of times. Before I knew it I was hanging out with these guys days on end, recording songs in the studio. They would also make cassette tapes with Toto music, for which I would do the singing. I would get 500 kuai [±80$] for it, which got me through another month. I lived on the campus anyway, and did not need much to get by.”

“I’ve always felt very welcome, and our interest was mutual. I wanted to play music with them, and they needed a guitar player. The fact that I was foreign didn’t matter – we were all equals. I stopped going to Chinese classes at university, but in the meantime, my Chinese was improving every day because I was talking to my new friends. I once went back to class in the second semester and discovered I was ahead of the others. By then I couldn’t just properly order food – I was talking Chinese the whole time.”

THE EARLY DAYS OF ROCK IN CHINA

“The years from 1986-1989 were the blossoming days for rock music – those were the days of liberation.”

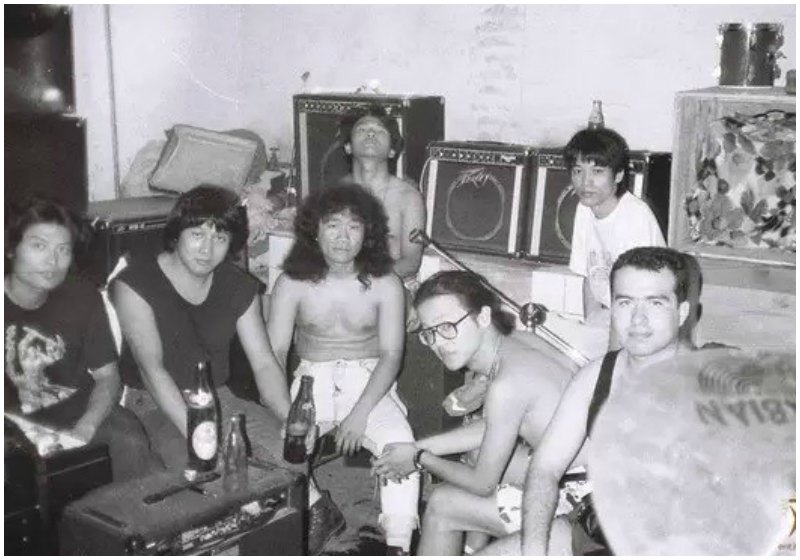

Heibao band members (Zhihu).

Heibao band members (Zhihu).

“The years from 1986-1989 were the blossoming days for a new type of music in China, but it was more than that: those were the days of liberation. Everybody thought: we’re opening up, we’re becoming modern. It was the build-up to the student movement of ’89. Rock music was a big part of it.”

“The late ‘80s were not necessarily the beginning of pop music in China, as you also had music by Chinese pop queen Teresa Teng and others which was popular before that time. But the rock scene provided a different sound – it was not as sweet as Teresa Teng, and it was influenced by the cassettes that were passed around, which included sounds by Toto, The Police, Bob Marley, and other artists. The difference between pop and rock is lifestyle; it was no music for the millions, it was a hip and alternative scene.”

“The ‘rock scene’ maybe consisted of 30 to 40 people. Cui Jian played an important role in those early days of rock. For many young adults, he was that critical voice against the authorities. He was very good with language, and also used Chinese instruments in his music. He really knew how to do it. Nobody ever surpassed him in that way.”

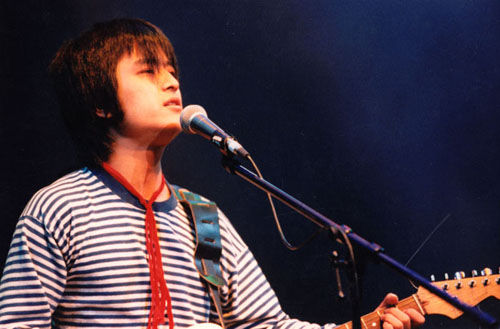

Cui Jian in 1990.

Cui Jian in 1990.

“Many musicians of those days were part of danwei’s [work units] focused on dance and music. Most of them were able to play a traditional Chinese instrument. They all came from a musical environment, but their power was to give those Chinese musical influences a new twist and combine them with the music that came in via Europe or America. In the music from those days, you can clearly hear what they listened to. Part of it is coincidence; Cui Jian sometimes only sounds like The Police because that was the cassette tape that happened to be available to him, while others weren’t.”

The Heibao band 黑豹乐队 (image from my.isself).

The Heibao band 黑豹乐队 (image from my.isself).

“Heibao (黑豹乐队, Black Panther) was a band that was also formed at the time. They later became the best-selling mainland Chinese rock band ever. More people started engaging with the rock scene. The simple core value in the beginning was that everyone just wanted to make music. Those were the free days. We would hang out together in the studio and if we went out we would hop on our bikes and cycle through the city. The streets were pretty empty. Looking back, I mainly remember that feeling of freedom and spontaneity. ”

THE TIANANMEN MOVEMENT

“The army had taken over the city. There was no more music, no more nothing.”

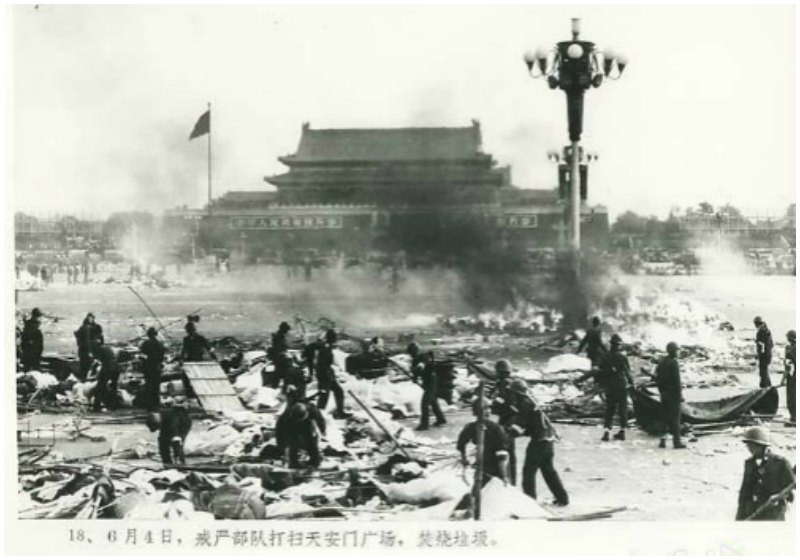

The aftermath: cleaning up Tiananmen Square, June 1989.

The aftermath: cleaning up Tiananmen Square, June 1989.

“I lived in Beijing throughout 1987-1988 and then went back in 1989. The liberal politician Hu Yaobang died in April 1989 and everyone mourned his death because he was a reformer who inspired people – he was, amongst others, against corruption. He was very popular amongst Chinese students. University students in Beijing went through the city in a procession to honour him and then the slogans started coming against corruption. It became political very quickly.”

“I arrived again in Beijing with a crew on the day Hu Yaobang died to make a documentary about youth culture in China for Dutch television and we recorded everything. For us, it was a coincidence that we arrived exactly at that moment, and we saw more and more international press arriving while we were filming all along. We only later realised how big this event actually was. It was one big roller coaster.”

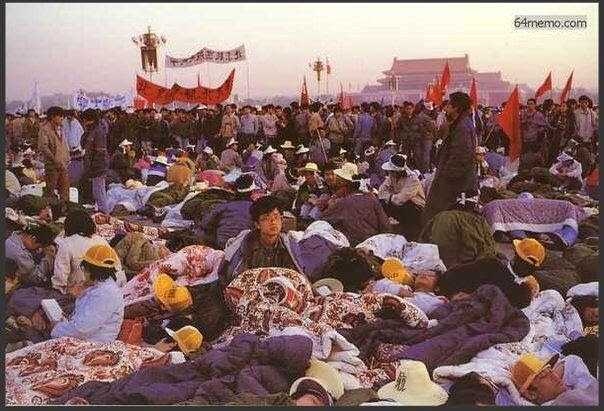

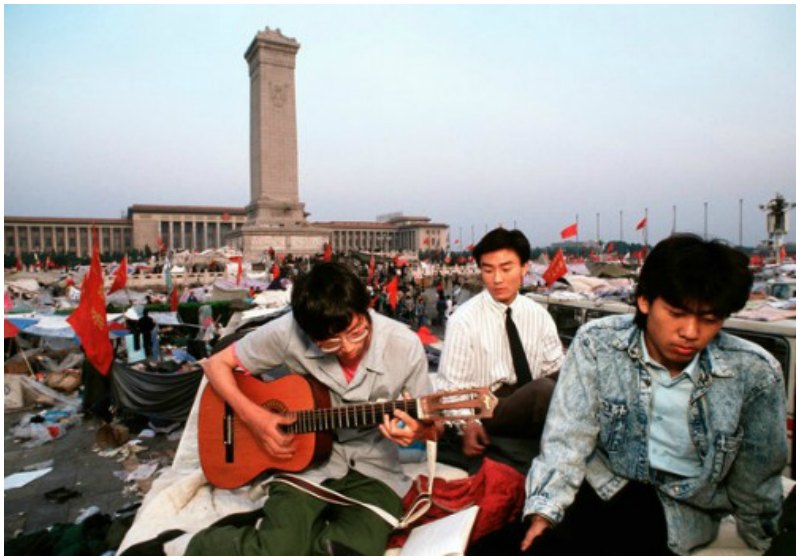

Picture of Tiananmen square protests, 15 May 1989 (source).

Picture of Tiananmen square protests, 15 May 1989 (source).

“We were staying at the Peking University campus, and saw more and more trucks coming and going with students hopping on to go to Tiananmen Square. If I had to compare it with anything, I’d say it was like Woodstock – a bizarre hopeful and loving vibe was capturing Beijing. I absolutely loved it, and I was one of the hundred-thousands of people standing on Tiananmen. We would go there all the time, also in the middle of night, and all my friends from the music scene would also be there to provide entertainment to the students who stayed there.”

“Cui Jian’s Tiananmen performance was legendary. His songs also made sense, singing about ‘I’ve got nothing to my name’ [see song translation]; he voiced the feelings many had the time. But there were a lot more people there who made music, there were many from the art and music scene. Students were even setting up a Statue of Liberty on Tiananmen. It was one big party.”

“At a certain point I realized that things were going the wrong way; things started to get dirty, literally, and I was too caught up – although I wasn’t politically involved at all. It was just that there were many cute girls and it was all so rock ’n roll, and I enjoyed it, but I got it all wrong. People started getting tired and not much was really happening. The height of the moment was gone. The same familiar faces were appearing in the media and the atmosphere changed. We decided to go to Shanghai by the end of May to further work on our documentary there.”

(Image by New York Times.)

(Image by New York Times.)

“It was night in Shanghai, on June 4th, when there was a quiet procession throughout Nanjing Avenue with people carrying big posters. On the trees we saw stapled faxes with images that had gotten through via Hong Kong about what had happened in Beijing. We saw dead people and burnt soldiers. I almost couldn’t believe it – that such a peaceful and care-free time had turned into such a dark thing. We did not return to Beijing afterwards, as we had nothing to do there anymore. People from the Dutch embassy in Beijing went to the campus to collect our photos and films to make sure they were safe. The army had taken over the city. There was no more music, no more nothing.”

“In those last months of 1989 and in the early nineties I went back to Beijing, but things had changed a lot – especially in the music scene. There were a lot of wild parties, but everything had become more underground. Many musicians endured hard times during those days.”

AFTER THE EIGHTIES

“Many of the guys from those days have gone mad.”

Beijing musicians at funeral of bassist Zhang Ju of band Tang Dynasty (founded by Kaiser Kuo with Ding Wu and Zhang Ju in 1988). Zhang died in a motorcycle accident in 1995. From left: Zhang Ling (Mayday), Zhu Jia, Zhou Ren (Xiutie/Pork), Jin Hai, Li Ji (Budaoweng) and Li Jie. Photo by Gao Yuan).

Beijing musicians at funeral of bassist Zhang Ju of band Tang Dynasty (founded by Kaiser Kuo with Ding Wu and Zhang Ju in 1988). Zhang died in a motorcycle accident in 1995. From left: Zhang Ling (Mayday), Zhu Jia, Zhou Ren (Xiutie/Pork), Jin Hai, Li Ji (Budaoweng) and Li Jie. Photo by Gao Yuan).

“People living in a dictatorship develop techniques to know the margins within which they can operate. In the early nineties, I noticed that the guys in the music scene somehow always knew when their friends were getting out of prison. Or when they could organise a party. It was also the time when Ecstacy came up – it was called yáotóuwán (摇头丸) in Chinese, literally: ‘shake-head-pill’, ’cause it made their heads shake.”

“It seems like not many people were able to pick up the music vibe where it had left off before those dark days in 1989. Some just couldn’t get on with the changing times, others were on drugs. Not many were arrested, but there were a lot of them who had to lay low for a long time after 1989. Zhang [Ado drummer] committed suicide last year. He Yong is now either imprisoned or in a mental hospital. Many of the guys from those days have gone mad or suffered a severe setback after their moment in those early flourishing days of rock had passed.”

“Now the music scene seems to be somewhat blooming again. Beijing really has got some good bands. Shanghai has got a nice jazz scene. But there is no solid base for these bands to build on. Japan and Korea are far ahead of China when it comes to the music scene. In China’s music scene, people are more individualistic – they are staring at the ground when you want to find the groove together. If everyone is only looking to do their own thing and don’t work together, you don’t get that music to the next level.”

“After living in China, I continued my own musical career in the Netherlands as a musician and producer. China never really influenced my career back home. But I did once produce a song in Chinese for Dutch singer Brigit Schuurman. I still go back to Beijing and get on stage every now and then. Last year I performed in Yugong Yishan together with Li Ji (Jige) from the band Budaoweng (不倒翁). I’m also working on recording a duet between Shanghai musician and friend Coco Zhao and my wife [Dutch singer Monique Klemann].”

Den Hengst in Beijing in 2015 with good friend and fellow musician Li Ji (aka Jige) on his right and two Taiwan friends from the rock scene.

Den Hengst in Beijing in 2015 with good friend and fellow musician Li Ji (aka Jige) on his right and two Taiwan friends from the rock scene.

“I will go back again this Summer and I will perform again. Somehow I always get that same nostalgic feeling I had in the Spring of 1989 when I walk on the streets of Beijing – that feeling of freedom, that anything’s possible.”

Den Hengst dressed in full attire for Hardrock Karaoke (left) and on the right during live performance. In the featured image, Den Hengst is performing at Yugong Yishan in 2015.

Den Hengst dressed in full attire for Hardrock Karaoke (left) and on the right during live performance. In the featured image, Den Hengst is performing at Yugong Yishan in 2015.

This interview was conducted and condensed by Manya Koetse in Amsterdam.

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

What began as K-pop fan outrage targeting a snarky commenter quickly escalated into a Baidu-linked scandal and a broader conversation about data privacy on Chinese social media.

Published

1 month agoon

March 26, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For an ordinary person with just a few followers, a Weibo account can sometimes be like a refuge from real life—almost like a private space on a public platform—where, along with millions of others, they can express dissatisfaction about daily annoyances or vent frustration about personal life situations.

But over recent years, even the most ordinary social media users could become victims of “opening the box” (开盒 kāihé)—the Chinese internet term for doxxing, meaning the deliberate leaking of personal information to expose or harass someone online.

A K-pop Fan-Led Online Witch Hunt

On March 12, a Chinese social media account focusing on K-pop content, Yuanqi Taopu Xuanshou (@元气桃浦选手), posted about Jang Wonyoung, a popular member of the Korean girl group IVE. As the South Korean singer and model attended Paris Fashion Week and then flew back the same day, the account suggested she was on a “crazy schedule.”

In the comment section, one female Weibo user nicknamed “Charihe” replied:

💬 “It’s a 12-hour flight and it’s not like she’s flying the plane herself. Isn’t sleeping in business class considered resting? Who says she can’t rest? What are you actually talking about by calling this a ‘crazy schedule’..”

Although the comment may have come across as a bit snarky, it was generally lighthearted and harmless. Yet unexpectedly, it brought disaster upon her.

That very evening, the woman nicknamed Charihe was bombarded with direct messages filled with insults from fans of Jang Wonyoung and IVE.

Ironically, Charihe’s profile showed she was anything but a hater of the pop star—her Weibo page included multiple posts praising Wonyoung’s beauty and charm. But that context was ignored by overzealous fans, who combed through her social media accounts looking for other posts to criticize, framing her as a terrible person.

After discovering through Charihe’s account that she was pregnant, Jang Wonyoung’s fans escalated their attacks by targeting her unborn child with insults.

The harassment did not stop there. Around midnight, fans doxxed Charihe, exposing her personal information, workplace, and the contact details of her family and friends. Her friends were flooded with messages, and some were even targeted at their workplaces.

Then, they tracked down Charihe’s husband’s WeChat account, sent him screenshots of her posts, and encouraged him to “physically punish” her.

The extremity of the online harassment finally drew backlash from netizens, who expressed concern for this ordinary pregnant woman’s situation:

💬 “Her entire life was exposed to people she never wanted to know about.”

💬 “Suffering this kind of attack during pregnancy is truly an undeserved disaster.”

Despite condemnation of the hate, some extreme self-proclaimed “fans” remained relentless in the online witch hunt against Charihe.

Baidu Takes a Hit After VP’s 13-Year-Old Daughter Is Exposed

One female fan, nicknamed “YourEyes” (@你的眼眸是世界上最小的湖泊), soon started doxxing commenters who had defended her. The speed and efficiency of these attacks left many stunned at just how easy it apparently is to trace social media users and doxx them.

Digging into old Weibo posts from the “YourEyes” account, people found she had repeatedly doxxed people on social media since last year, using various alt accounts.

She had previously also shared information claiming to study in Canada and boasted about her father’s monthly salary of 220,000 RMB (approx. $30.3K), along with a photo of a confirmation document.

Piecing together the clues, online sleuths finally identified her as the daughter of Xie Guangjun (谢广军), Vice President of Baidu.

From an online hate campaign against an innocent, snarky commenter, the case then became a headline in Chinese state media, and even made international headlines, after it was confirmed that the user “YourEyes”—who had been so quick to dig up others’ personal details—was in fact the 13-year-old daughter of Xie Guangjun, vice president at one of China’s biggest tech giants.

On March 17, Xie Guangjun posted the following apology to his WeChat Moments:

💬 “Recently, my 13-year-old daughter got into an online dispute. Losing control of her emotions, she published other people’s private information from overseas social platforms onto her own account. This led to her own personal information also getting exposed, triggering widespread negative discussion.

As her father, I failed to detect the problem in time and failed to guide her in how to properly handle the situation. I did not teach her the importance of respecting and protecting the privacy of others and of herself, for which I feel deep regret.

In response to this incident, I have communicated with my daughter and sternly criticized her actions. I hereby sincerely apologize to all friends affected.

As a minor, my daughter’s emotional and cognitive maturity is still developing. In a moment of impulsiveness, she made a wrong decision that hurt others and, at the same time, found herself caught in a storm of controversy that has subjected her to pressure and distress far beyond her age.

Here, I respectfully ask everyone to stop spreading related content and to give her the opportunity to correct her mistakes and grow.

Once again, I extend my apologies, and I sincerely thank everyone for your understanding and kindness.”

The public response to Xie’s apology has been largely negative. Many criticized the fact that it was posted privately on WeChat Moments rather than shared on a public platform like Weibo. Some dismissed the statement as an attempt to pacify Baidu shareholders and colleagues rather than take real accountability.

Netizens also pointed out that the apology avoided addressing the core issue of doxxing. Concerns were raised about whether Xie’s position at Baidu—and potential access to sensitive information—may have helped his daughter acquire the data she used to doxx others.

Adding fuel to the speculation were past conversations allegedly involving one of @YourEyes’ alt accounts. In one exchange, when asked “Who are you doxxing next?” she replied, “My parents provided the info,” with a friend adding, “The Baidu database can doxx your entire family.”

Following an internal investigation, Baidu’s head of security, Chen Yang (陈洋), stated on the company’s internal forum that Xie Guangjun’s daughter did not obtain data from Baidu but from “overseas sources.”

However, this clarification did little to reassure the public—and Baidu’s reputation has taken a hit. The company has faced prior scandals, most notably a the 2016 controversy over profiting from misleading medical advertisements.

Online Vulnerability

Beyond Baidu’s involvement, the incident reignited wider concerns about online privacy in China. “Even if it didn’t come from Baidu,” one user wrote, “the fact that a 13-year-old can access such personal information about strangers is terrifying.”

Using the hashtag “Reporter buys own confidential data” (#记者买到了自己的秘密#), Chinese media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily (@南方都市报) recently reported that China’s gray market for personal data has grown significantly. For just 300 RMB ($41), their journalist was able to purchase their own household registration data.

Further investigation uncovered underground networks that claim to cooperate with police, offering a “70-30 profit split” on data transactions.

These illegal data practices are not just connected to doxxing but also to widespread online fraud.

In response, some netizens have begun sharing guides on how to protect oneself from doxxing. For example, they recommend people disable phone number search on apps like WeChat and Alipay, hide their real name in settings, and avoid adding strangers, especially if they are active in fan communities.

Amid the chaos, K-pop fan wars continue to rage online. But some voices—such as influencer Jingzai (@一个特别虚荣的人)—have pointed out that the real issue isn’t fandom, but the deeper problem of data security.

💬 “You should question Baidu, question the telecom giants, question the government, and only then, fight over which fan group started this.”

As for ‘Charihe,’ whose comment sparked it all—her account is now gone. Her username has become a hashtag. For some, it’s still a target for online abuse. For others, it is a reminder of just how vulnerable every user is in a world where digital privacy is far from guaranteed.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Published

2 months agoon

March 1, 2025

PART OF THIS TEXT COMES FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Over the past few weeks, the Chinese blockbuster Ne Zha 2 has been trending on Weibo every single day. The movie, loosely based on Chinese mythology and the Chinese canonical novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), has triggered all kinds of memes and discussions on Chinese social media (read more here and here).

One of the most beloved characters is the leopard demon Shen Gongbao (申公豹). While Shen Gongbao was a more typical villain in the first film, the narrative of Ne Zha 2 adds more nuance and complexity to his character. By exploring his struggles, the film makes him more relatable and sympathetic.

In the movie, Shen is portrayed as a sometimes sinister and tragic villain with humorous and likeable traits. He has a stutter, and a deep desire to earn recognition. Unlike many celestial figures in the film, Shen Gongbao was not born into privilege and never became immortal. As a demon who ascended to the divine court, he remains at the lower rungs of the hierarchy in Chinese mythology. He is a hardworking overachiever who perhaps turned into a villain due to being treated unfairly.

Many viewers resonate with him because, despite his diligence, he will never be like the gods and immortals around him. Many Chinese netizens suggest that Shen Gongbao represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years. According to Baike, it first popped up on a Douban forum dedicated to discussing the struggles of students from China’s top universities. Although the term has been part of social media language since 2020, it has recently come back into the spotlight due to Shen Gongbao.

“Small-town swot” refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often find they lack the same social advantages, connections, and networking opportunities as their urban peers.

The idea that they remain at a disadvantage despite working so hard leads to frustration and anxiety—it seems they will never truly escape their background. In a way, it reflects a deeper aspect of China’s rural-urban divide.

Some people on Weibo, like Chinese documentary director and blogger Bianren Guowei (@汴人郭威), try to translate Shen Gongbao’s legendary narrative to a modern Chinese immigrant situation, and imagine that in today’s China, he’d be the guy who trusts in his hard work and intelligence to get into a prestigious school, pass the TOEFL, obtain a green card, and then work in Silicon Valley or on Wall Street. Meanwhile, as a filial son and good brother, he’d save up his “celestial pills” (US dollars) to send home to his family.

Another popular blogger (@痴史) wrote:

“I just finished watching Ne Zha and my wife asked me, why do so many people sympathize with Shen Gongbao? I said, I’ll give you an example to make you understand. Shen Gongbao spent years painstakingly accumulating just six immortal pills (xiāndān 仙丹), while the celestial beings could have 9,000 in their hand just like that.

It’s like saving up money from scatch for years just to buy a gold bracelet, only to realize that the trash bins of the rich people are made of gold, and even the wires in their homes are made of gold. It’s like working tirelessly for years to save up 60,000 yuan ($8230), while someone else can effortlessly pull out 90 million ($12.3 million).In the Heavenly Palace, a single meal costs more than an ordinary person’s lifetime earnings.

Shen Gongbao seems to be his father’s pride, he’s a role model to his little brother, and he’s the hope of his entire village. Yet, despite all his diligence and effort, in the celestial realm, he’s nothing more than a marginal figure. Shen Gongbao is not a villain, he is just the epitome of all of us ordinary people. It is because he represents the state of most of us normal people, that he receives so much empathy.”

In the end, in the eyes of many, Shen Gongbao is the ultimate small-town swot. As a result, he has temporarily become China’s most beloved villain.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

The Liaoyang Restaurant Fire That Killed 22 People

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

Aftermath of Suzhou Marathon’s “Pissing Gate”

Do You Know Who Li Gang Is? Anti-Corruption Official Arrested for Corruption

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

Collective Grief Over “Big S”

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital11 months ago

China Digital11 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers12 months ago

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers12 months agoA Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea