China Memes & Viral

The Rise of China’s “Special Forces Travel”: The Mission to Get the Ultimate Budget Trip in Limited Time

Fun, fast, frugal: this Chinese travel trend is all about doing as much as possible at a low price within a limited time.

Published

3 years agoon

By

Zilan Qian

This Labor Day holiday, ‘special forces travelers’ are flooding popular tourist spots across China. Their mission is clear: covering as many places as possible at the lowest cost and within a limited time. While the travel trend has become a social media hype, there are also those criticizing the trend for being superficial and troublesome.

Social media platforms in China are witnessing the emergence of a new trend in short videos and posts featuring content tagged as “college student special forces” (大学生特种兵).

These posts showcase vloggers’ travels in a particular location, featuring a compilation of photos and video clips of famous tourist destinations. The videos typically begin with the title “College Student Special Forces: 24/48 hours Eating/Exploring [Location]” (大学生特种兵之24/48小时吃/玩遍xx), followed by stylish sentences to provide more context.

The official Weibo account of Sichuan Radio and Television’s Sichuan Observation featured one particular “college student special forces” video that showcased a 24-hour eating tour of Sichuan. The video included photos of various Sichuan dishes, such as Bo Bo chicken (钵钵鸡), tofu pudding (豆腐脑), and shaved ice dessert (冰粉), with succinct commentary such as “[xxx food] has been eaten” accompanying each dish.

This collage features four dishes showcased in the videos. The top row, from left to right, shows ice dessert and bobo chicken; the bottom row features tofu pudding and potato pancake. Screenshots via video.

These videos showcase a new trend in domestic travel called “special forces style traveling.” According to an article by Hongxing News on Weibo, this type of travel is characterized by short durations, visits to numerous tourist spots, low expenses, and excitement.

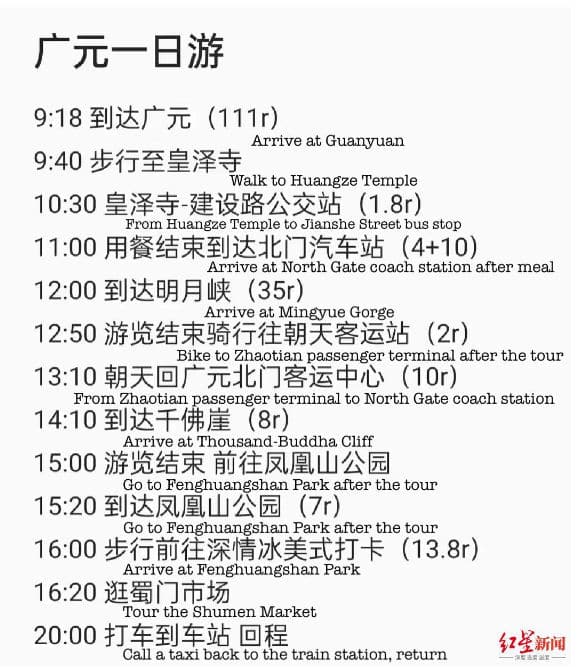

The article provides an example of this travel style by featuring a college student’s one-day itinerary to Guangyuan in Sichuan. In the itinerary, the student arrives in Guangyuan at 9 am, visits eight tourist spots, and returns to school by 11 pm, spending a total of 202 RMB [$29]. This amount includes the cost of train tickets (111 RMB/$16), entrance fees to tourist spots, local transportation, and meals.

This photo displays the travel itinerary of the college students from the original Weibo article, including the expenses in RMB indicated in the brackets. The author has provided a translation of the itinerary for reference.

This 11-hour travel experience is perhaps only a moderate version of the ‘special forces’ style, which can sometimes be extreme.

According to an article by Toutiao News, two first-year college students left their campus on Friday after class and took a 10-hour train ride to Beijing, arriving at 5:30 am on Saturday. Despite the long journey, they stayed up all night on Saturday to witness the flag-raising ceremony in Tiananmen Square at 3 am on Sunday.

Similarly, one graduate student spent a day at World Studio and then embarked on a late-night climb up Mount Taishan – the highest of the five sacred mountains in China, – at 11 pm on Friday. She then traveled to Jinan at noon for lunch and sightseeing, and headed to Zibo at night for barbecue on Saturday before departing for Beijing at 11 pm.

Remarkably, all of these students managed to return to school in time for their Monday morning classes as usual.

Compilation of posts showing extreme travel schedules, such as: arriving in Beijing at 5:45; 6:10 Nanluoguxiang; 7:00 Gulou; 8:30 Palace Museum; 11:00 moat of the Forbidden City; 14:00 Lama Temple; 15:40 Summer Palace; 21:00 Tiananmen Square.

The rise of the “special forces” style of travel has garnered support from Chinese netizens and media outlets alike.

Xinjing News reports that this approach demonstrates young people’s consideration for time and cost, as well as their ability to adapt to fast-paced environments.

Others also see it as a way for college students to seize the day and build resilience by facing challenges head-on. Local media outlets have also embraced the “special forces” concept as a marketing strategy to promote tourism. They create and promote travel itineraries that showcase all the area’s tourist attractions in under half a minute through short videos.

A screenshot from Hangzhou Public Security’s Weibo post on a new “special forces” style travel route that covers seven tourist spots. Tourists are encouraged to meet with the public security forces at each spot in exchange for special gifts from Hangzhou Public Security.

Despite the hype surrounding the trend, there are also concerns and annoyances about this form of travel.

Some think the trend is unhealthy. As a Weibo post by China News Weekly warns, this travel style, with high-intensity exercise and deprivation of sleep, can be be bad for your health (#特种兵式旅游存在健康隐患#).

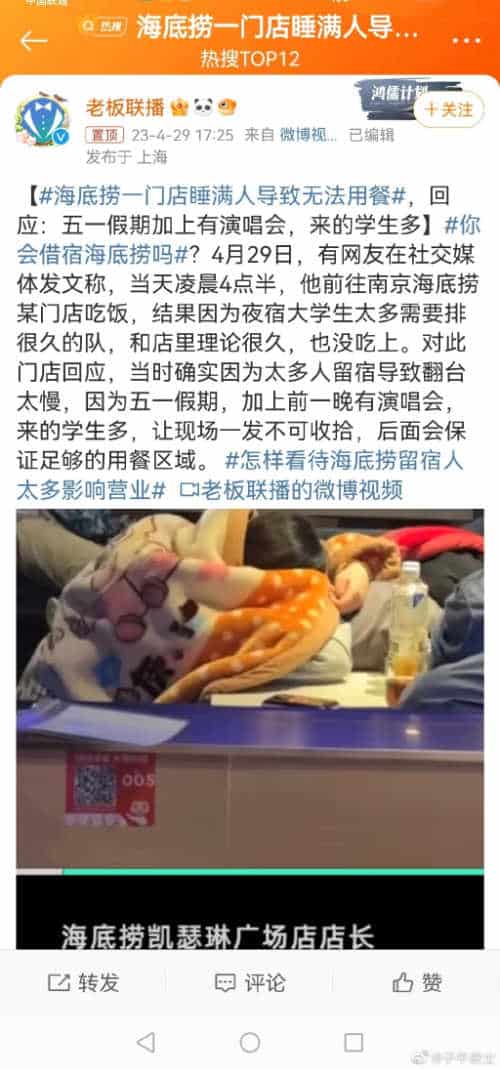

Others are more annoyed about the “special force” travelers becoming a nuisance to others due to their frugality. One recent viral hashtag was about so many travelers sleeping at the tables of a 24-hour Haidilao hotpot restaurant that they were unable to serve other customers (#海底捞一门店睡满人导致无法用餐#).

Sleeping at Haidilao.

According to a Weibo post pinned on top of the hashtag page, many college students slept in the restaurant after finishing their meals because of the many performances happening in Nanjing during the Labor Day holiday (五一假期). One Weibo user made a playful comment under the hashtag, joking about the frugality of this type of travel: “It seems like this is a special forces trip after all. The main feature is to simply have a roof over your head.”

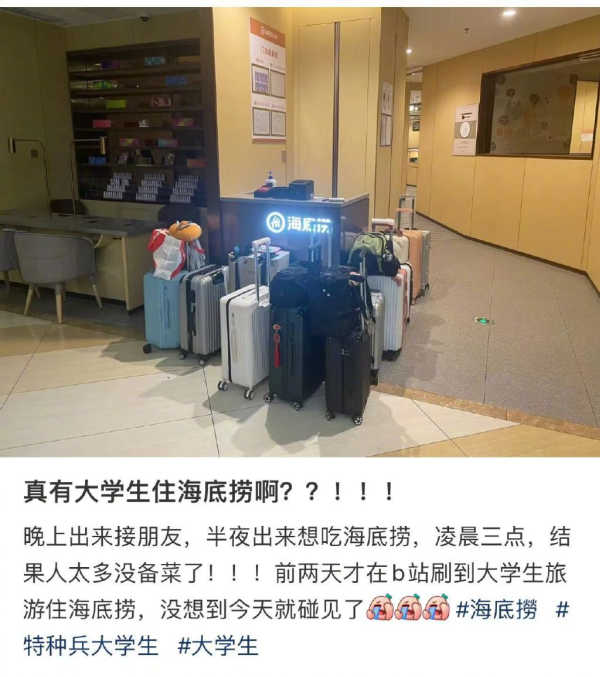

A photo from Vista’s Weibo post under the hashtag. Haidilao restaurant customers complain about queuing up at 3 am because of college students sleeping in the shop, showing students’ suitcases outside the restaurant.

Other netizens also question how meaningful this kind of travel style is: does the “special forces” traveler actually experience local culture, or are they just flaunting their travels for social media and skimming over everything without learning anything? The word used is zǒumǎ guān huā (走马观花), which literally means glancing over flowers while riding on horseback: having a superficial understanding from cursory observation.

As one user of the Q&A platform Zhihu comments, this travel style simply enables people to “punch the clock” (打卡, showing to have acquired something new or traveled somewhere) or “clock in” to many places in order to post about it on WeChat or Tiktok: “There is actually no difference compared to to the old travel style of ‘sleeping on the bus, taking photos off the bus’ (上车睡觉,下车拍照)’. Both [kind of travelers] return home with nothing learned.”

Despite raising some criticism, many people view the “special forces” style of travel as a choice made due to limited economic resources and time.

In response to the question, “What does ‘special forces’ style show? Do we forget the meaning of traveling in this fast-paced society?” one Zhihu user explained that for many people, their limited time and financial resources prevent them from fully realizing the meaning of traveling: “Taking a vacation means having to make up for missed workdays, and even working hard doesn’t bring in much money. The workload is so heavy that if you can take a break and have some fun, that’s already pretty good. Meaningful travel…that belongs to the wealthy.”

On the other hand, another Zhihu commenter also challenges the idea of “meaningful travel” by claiming that the so-called “meaning” of travel is a subjective experience: “Any experience is a good experience when you’re young, as long as it’s not illegal or dangerous. Why would others want to ruin their excitement?”

“Only you can add meaning to your travels,” another commenter writes: “The ‘special forces travel’ is fresh, and it’s fun (..) Don’t dive in too much on whether it’s meaningful or not. There’s so many different ways of things being meaningful. For many things, it’s just about doing it, and if you like it, then you keep doing it and otherwise you stop. It’s basically what life is all about.”

By Zilan Qian

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles. Follow us on Twitter here.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Zilan Qian is a China-born undergraduate student at Barnard College majoring in Anthropology. She is interested in exploring different cultural phenomena, loves people-watching, and likes loitering in supermarkets and museums.

China Celebs

China Trend Watch: Quiet Nationalism, Loud Statements, and Nanjing Memorial Day

From war memory to viral eggs, salty cakes, an unfortunate dinner party and farewell to an iconic actress.

Published

4 weeks agoon

December 14, 2025

🔥 China Trend Watch — Week 50 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to the Eye on Digital China newsletter. This is the China Trend Watch edition — a quick catch-up on real-time conversations.

I’ve rounded up my latest China trip that brought me from Chongqing to Nanjing, Wuhan, Zaozhuang and Beijing, for some of my research on Chinese remembrances of war. Along the way, I have met many friendly people and had interesting converations, from hanging out with a group of Wuhan teenagers to lively conversations with retired seniors in Shandong.

A small and short personal observation, if I may, regarding the current tensions between China and Japan.

I vividly remember the atmosphere on the streets during earlier moments when tensions ran sky-high—most notably in 2012, after a major diplomatic crisis erupted over Japan’s nationalization of several disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. That episode triggered large-scale anti-Japanese protests across China and spilled unmistakably into everyday life. In Beijing’s Sanlitun area, for instance, there was a street food vendor who put up a large sign proclaiming, “The Diaoyu Islands belong to China.” In the hutong neighborhoods, it seemed as though virtually every household had hung a Chinese flag by its door. Books about Japan that I purchased locally later turned out to have entire pages ripped out. My favorite sushi restaurant suddenly displayed a sign explaining that its brand was, in fact, very Chinese and had nothing to do with Japan. Nearby, in the clothing markets around the Beijing Zoo, T-shirts bearing nationalistic slogans related to the islands dispute were on sale at multiple stalls.

By contrast, during my most recent stay in Nanjing and beyond—despite the increasingly militant tone of state media and social media campaigns surrounding Japan, and despite the undeniable persistence of anti-Japanese sentiment—I noticed far fewer visible expressions of it in daily life. There were no slogan T-shirts, no banners, no overt street-level signaling. While news came out that a string of Japanese performances in China were canceled, I noticed hotel waitress fully dressed in a Japanese kimono at an in-house Japanese restaurant. Local bookstores are filled with works by Japanese authors, and Japanese popular culture appear to be thriving and coexisting comfortably with China’s own flourishing ACG (anime, comics, and games) industry.

Is there simply less anti-Japanese sentiment than over a decade ago? Or is it, perhaps, that in today’s highly digitalized Xi Jinping era, nationalist narratives are more tightly managed and increasingly channeled online—making people more cautious, more restrained, or simply less inclined to express political sentiments openly in public space?

A cab driver in Chongqing told me he believed there was “something wrong” with Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi and the influence she has had on bilateral relations since her rise to power. While supporting his government’s tough stance and expressing sadness over the scars left by war, he also mentioned that he had enjoyed a pleasant conversation earlier that same morning with a young Japanese man he had driven to the train station.

“We didn’t talk about the latest clash,” he said. “If find that too sensitive to mention. He spoke Chinese, he studied Chinese, like you. I don’t hate today’s Japanese people at all. In the end, we’re all just people. What’s happening now is something between the leadership.”

He spoke at length while driving me to the station, signaling that the topic clearly weighed on him. It left me with the sense that the absence of banners or T-shirts does not mean the issue has faded from everyday life, only that it is not expressed as a mass spectacle like it was in earlier years. It has become quieter, more online, and more filtered through official narratives, but it is still very much alive.

There is a lot more to say, but it is Sunday after all, and there is plenty more to read here, so let’s dive in.

- 🍓 Chinese consumers were pretty salty this week when discovering their pricey strawberry cake from Alibaba supermarket chain Hema (盒马) tasted all wrong. Hema acknowledged a production issue (they didn’t say it outright, but salt was allegedly used instead of sugar) and the incident triggered discussions about food safety & quality control in automated food production, especially when such a major mistake happens at high-profile companies.

- 🌡️ China’s announced ban on mercury thermometers (as of Jan 1st 2026) has sparked a buying frenzy, as many consumers, reluctant to switch to electronic alternatives, still prefer mercury models for their perceived accuracy and convenience. Despite nearly half of annual mercury poisoning cases being linked to broken thermometers, prices have now surged from around 4 yuan ($0.6) to over 30 yuan ($4.25), and stores have reported complete sellouts.

- ❄️ Beijing welcomed its first snowfall of winter 2025 this week, leading to lovely social media pics and the Beijing Palace Museum tickets selling out instantly. Experiencing and capturing that first snowfall at the Forbidden City has become somewhat of a holy grail on social media.

- 🕵️♂️ A local construction site in Shanghai unexpectedly became the scene of a modern-day treasure hunt after dozens of residents armed with shovels and metal detectors rushed to the area following online rumors that silver coins (including valuable older ones) had been found. Authorities had to intervene and, while not confirming the rumors, emphasized that any buried cultural relics belong to the state.

- 🇷🇺 Since this month, Chinese citizens can enter Russia visa-free for up to 30 days, a policy that led Chinese state media to claim that “Russia is replacing Japan as a new favorite among Chinese tourists.” On social media, however, the vibe is different, with travelers complaining about high prices, poor internet, lack of online payments, unreliable ATMs, and the need for thorough trip preparation — all reasons why Russia is unlikely to become the go-to destination for the Chinese New Year.

- 🫏 An investigation by Beijing Evening News revealed that many of the capital’s popular donkey meat sandwich shops are actually serving horse meat without informing customers. China’s donkey shortage — driven by declining domestic supply, rising demand for the traditional Chinese medicine Ejiao (which uses donkey hides), and an African export ban — has been a hot topic this year. Now that it’s directly affecting a beloved delicacy, the issue is drawing even more public attention.

1. Why This Year’s Nanjing Memorial Day Felt Different

Posters published by various Chinese state media outlets to commemorate the Nanjing Massacre.

December 13 marked the 88th anniversary of the fall of Nanjing, and this year’s Nanjing Memorial Day (南京大屠杀难者国家公祭日), although described as a low-key commemoration by foreign media, was trending all over Chinese social media.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, on December 12, 1937, the Japanese army attacked Nanjing from various directions, and defending Chinese forces suffered heavy casualties. A day later, the city was captured. It marked the beginning of a six-week-long massacre filled with looting, arson, and rape, during which, according to China’s official data, at least 300,000 residents, including children, elderly, and women, were brutally murdered.

This year, the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Day, which was first officially held as a state-level event in 2014, carried extra weight. This dark chapter of history has continuously been a sensitive topic in Sino-Japanese relations, but with recent diplomatic tensions between the two countries reaching new heights, the Memorial Day was especially tied to current-day relations between China and Japan and to Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who has been described by Chinese media as an “ultranationalist” with tendencies to downplay Japan’s wartime aggression. Takaichi’s November 2025 parliamentary statement that a Chinese military action against Taiwan could be considered a “survival-threatening situation” for Japan, allowing for the deployment of its Self-Defense Forces, continues to fuel Chinese anger.

The link between history and current-day bilateral relations was visible not only on social media, but also during the commemoration itself, where Shi Taifeng (石泰峰), head of the ruling Communist Party’s Organization Department, said that any attempt to revive militarism and challenge the postwar international order is “doomed to fail.”

Besides the many online posters disseminated by Chinese official accounts on social media focusing on mourning, quiet commemoration, and honoring the lives of the 300,000 Chinese compatriots killed in Nanjing, one official online visual stood out for displaying a louder and more aggressive message—namely that posted by the official Weibo account of the Eastern Theater Command of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (@东部战区).

The visual posted by the PLA Eastern Theater Command, titled: Rite of the Great Saber (大刀祭).

The visual showed a strong hand holding a giant blood-stained blade that is beheading a skeleton wearing a helmet marked “militarism,” with images related to the Nanjing Massacre visible on the blade and, behind it, a map of East Asia. The number “300000” appears in red, dripping like blood. At the top, the characters read “Rite of the Great Saber” or “The Great Saber Sacrifice” (大刀祭).

The official account explained the visual, writing: “(…) 88 years have passed and the blood of the heroic dead has not yet dried, [yet] the ghost of militarism is making a comeback. Each year, on National Memorial Day, a deafening alarm is sounded, reminding us that we must—at all times hold high the great saber offered in blood sacrifice, resolutely cut off filthy heads, never allow militarism to return, and never allow historical tragedy to be repeated.”

The text’s “cut off filthy heads” phrasing is similar to part of a now-deleted tweet sent out last month by the Chinese Consul General in Osaka, Xue Jian (薛剑), who responded to Takaichi’s controversial Taiwan remarks by writing (in Japanese): “If you come charging in on your own like that, there’s nothing to do but cut that filthy neck down without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared?” (“勝手に突っ込んできたその汚い首は一瞬の躊躇もなく斬ってやるしかない。覚悟が出来ているのか。”)

The recent visuals, social media approach, and shifts in texts reflect a clear change in tone in Chinese official discourse regarding Japan and the memory of war, moving the narrative from victimhood toward a more confrontational and militant tone.

2. He Qing, China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty”, Passes Away at 61

He Qing. Images on the sides: the four famous roles in China’s most iconic tv dramas.

China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty” (古典第一美女), He Qing (何晴), who starred in all four of China’s most beloved and canonical television dramas, passed away on Saturday at the age of 61. On December 14, news of the famous actress’s passing was trending across virtually all Chinese social media apps.

Born in 1964 into an artistic family in Jiangshan, Zhejiang Province, He Qing received traditional Chinese opera (Kunqu) training at the Zhejiang Kunqu Opera Troupe. Her debut in the entertainment industry may have come by chance, as she reportedly once met Chinese director Yang Jie (杨洁) on a train, which led to her joining the production of Journey to the West (西游记), where she played Lingji Bodhisattva (灵吉菩萨).

In China, He Qing is remembered as a veteran actress in much the same way that some famous Hong Kong actresses became renowned for their beauty, iconic roles, and for essentially becoming household names. More than just glitter and glamour, He Qing was especially a symbol of classical Chinese beauty and literary culture. She was the only actress to star in screen adaptations of all four of China’s “Four Great Classical Novels” (演遍四大名著): besides Journey to the West (西游记, 1986), she also appeared in Dream of the Red Chamber (红楼梦, 1987), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义, 1994), and Water Margin (水浒传, 1998).

She was married to fellow actor Xu Yajun (许亚军), with whom she had a son, Xu He (许何). Although the two later divorced, she remained close to her ex-husband and even befriended his new (and fourth) wife, Zhang Shu (张澍).

In 2015, He Qing was diagnosed with a brain tumor. After her diagnosis, she withdrew from the entertainment industry to focus on her recovery and lived a low-key life in her later years.

Her passing has prompted an outpouring of tributes from Chinese netizens and colleagues in the entertainment industry. Mourning her loss comes with a sense of nostalgia for the past, and many have praised He Qing for her timeless beauty and authenticity, which will be remembered long after her passing.

3. And Then There Were None: Dinner Party of Ten Leaves One Man with the Bill

Ten dine together, nine slip away..one left for the bill, who he refused to pay…

Do you know that nursery rhyme where ten little soldiers disappear one by one until none remain at the end? That is more or less what happened earlier this month in Chongqing, when ten people dined together at a restaurant, but—once it came time to pay—nine people left one by one.

One had to answer a phone call, another had to use the restroom, and in the end, just before midnight, only Mr. Zhang was left, facing a bill of 1,262 yuan ($180), which he refused to pay. He argued that he could not afford it and that the dinner party hadn’t been initiated by him at all; as merely a participant, the bill shouldn’t have been his responsibility.

After the restaurant called the police, the organizer of the dinner was contacted. But he, too, said he couldn’t pay. Through police mediation, Mr. Zhang then wrote a written commitment promising to pay the bill the following day and left his ID as collateral, but he still failed to make the payment.

By now, the restaurant is planning to sue and has also contacted the Chinese media. According to Zhang, who apparently has been unable to contact his “friends” to collect the money: “I did make the promise, but if I pay the money, wouldn’t that make me a sucker?” (“我的确承诺了,但你说我把钱付了,我是不是冤大头啊”)

As the story went completely viral (by now, even Hu Xijin has weighed in) comment sections filled with broader social reflections on alcohol-fueled group gatherings and unclear payment rules, where one person sometimes ends up paying for everything despite feeling it wasn’t their role to do so. In this era of digital payments, many argue it should be easy enough to go Dutch and settle the bill immediately via a group payment app.

Although Zhang is seen by some as a victim, others argue that he is still a “sucker” for not paying after having promised to do so. As one commenter put it: “Out of the ten of them, not a single one is a good person.”

Real Person Vibes [活人感 (huóréngǎn)

Every December, the ten most popular buzzwords, key terms, or expressions of the year are listed by the Chinese linguistics magazine Yǎowén Jiáozì (咬文嚼字), selecting words that reflect present-day society and changing times. Each year, the list goes trending and is widely disseminated by Chinese media.

This week, the 2025 list was released, including terms such as Digital Nomads 数字游民 (shù zì yóu mín), Sū Chāo (苏超), referring to the hugely popular amateur Jiangsu Super League football competition, and “Pre-made ××” (预制, yù zhì), following a year filled with discussions about pre-fab and pre-made food (see article).

My favorite word on the list is “Real-Person Vibes” (活人感 huó rén gǎn). The term literally consists of three characters meaning “living – human – feeling,” and it describes people, stories, or things that feel unpolished, spontaneous, and unfiltered—something that has become increasingly relevant in a year dominated by AI-generated content and visuals.

Amid over-curated feeds and AI-produced text, we crave huóréngǎn: authenticity, small imperfections, and liveliness as an antidote to a digital, artificial world.

The 9:12 Boiled Egg That Took Over Douyin

How do you get a perfect boiled egg? A Douyin user known as “Loves Eating Eggs” (爱吃蛋) has become all the rage after leaving a precise comment on how to boil eggs. His advice: First boil the water, then add the eggs, boil for exactly 9 minutes and 12 seconds, remove, and immediately run under cold water.

That simple tip catapulted his follower count from around 200 to over 3.5 million in a single week (I just checked—he’s up to 4.2 million now).

The new viral hit is a 24-year-old self-proclaimed egg expert (of course, his English nickname should be the Eggxpert). He claims to have eaten 40 eggs a day for the past five years and knows exactly how every second of boiling, frying, or stirring affects an egg. He regularly posts videos showing eggs cooked for different lengths of time.

It has earned him the nicknames “Egg God” (蛋神) and “Boiled Egg Immortal” (煮蛋仙人), and has sent boiled eggs (9 minutes and 12 seconds exactly) all over social media feeds.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China China Trend Watch. For slower-moving trends and deeper structural analysis, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

Housekeeping reminder: if you’re receiving duplicate newsletters, it’s likely because you signed up on both the main What’s on Weibo website and the Eye on Digital China Substack. If you’re a paying member on one of the two, you may receive the premium newsletter twice. Please keep the one you’re paying for, and feel free to unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or

email me. First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

From Hong Kong’s Wang Fuk Court fire and China’s new “family member” rule to Japanese concerts halted, the Nantong viral remark, childcare subsidy payouts, 6G trials, and top social media debates.

Published

1 month agoon

December 2, 2025

🔥 China Trend Watch — Week 48–49 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China. This edition was sent to our subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of the China Trend Watch Eye on Digital China newsletter. I have been typing this newsletter from my phone and a tiny tablet on the trains from Chongqing to Wuhan and Wuhan to Nanjing, unfortunately tucked in the middle seat (that place where elbows suddenly become such inconvenient body parts), so please bear with me if spotting any inconsistensies or if the images don’t line up.

Chongqing has been a unique experience — a city in China that has been on my to-visit list for years. Its “cyberpunk” reputation doesn’t really do it justice. There’s this beautiful tension between its old history (century-old stairs, wartime tunnels) and the full speed of the future (neon lights, incredible skyscrapers), with the streets actually smelling like hotpot – such a special mix (or is that, perhaps, just what cyberpunk actually is?!).

Photos by me: View over Chongqing’s Shibati area, and toymachines in a wartime bomb shelter near Libazi.

This time, it was the city’s WWII history that finally pushed me to visit, as I’m on a research trip through several major cities that played important roles in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War — a topic that has become increasingly relevant over the past few months. I’ve already visited some fascinating places, from the former residence of General Stilwell to Chiang Kai-shek’s air-raid shelters and wartime military headquarters. Today I’ll be heading to some war-related museums in Nanjing. More on that later.

I will get back into my normal routine next week when I return from travels.

Let’s dive in.

- 🇨🇳 The 2025 Mnet Asian Music Awards (MAMA), one of the biggest K-pop award shows, sparked online backlash this week after netizens discovered that the event’s voting interface listed Hong Kong and Taiwan as separate countries in its selection menu. Seen as violating the ‘One China’ principle, netizens criticized MAMA for being disrespectful to China (meanwhile, the event was actually held in Hong Kong).

- 💰 As part of a national childcare subsidy plan announced earlier this year (initiated to boost China’s dropping birth rates and support low-income families), parents across the country are now receiving their initial 3,600 yuan ($508) payouts (per child aged 0–3 per year), creating an online buzz and reminding other parents to apply if they haven’t yet.

- 👀 Move over 5G…the 6G era is nearing! China has completed its first real-world testing trial of 6G applications. Being 100x faster than 5G, it’s the future mobile standard. Commercial use is planned for 2030.

- 🎬 Zootopia 2 is everywhere right now and has broken records in China with a US$267 million box office in 5 days. But despite its success there’s also been some backlash over the decision to cast celebrity actors for the main characters in the Chinese version instead of professional voice actors. Fans of the movie felt the performances were subpar, leading fans of the celebrities to defend them.

- 🚹 The 57-year-old Chinese actor and singer Sun Hao (孙浩) made headlines this week, and not for his latest work — but for getting caught urinating in public after a dinner with friends. The incident has triggered discussions about how (un)acceptable it is to pee on the street, and how celebrities should set the right example.

- 🛸 Blending classic Chinese humor with sci-fi elements, the new Chinese urban comedy Sarcastic Family (毒舌舌家) has become an online hit. The comedy is about a mother and daughter from another galaxy who become an unconventional family on planet Earth when the daughter marries a Chinese man, joined in a household by his father and her own outer-space mom.

1. The Hong Kong Wang Fuk Court Fire

The catastrophic residential fire at Hong Kong’s Wang Fuk Court in the city’s Tai Po district (香港大埔) has become the deadliest blaze in Hong Kong in 80 years.

The fire, which broke out on Wednesday at 14:51 local time, spread so quickly that it soon covered a total of seven residential towers. Initially, news came out that the fire had killed at least 13 and injured 28, but the figures soon kept rising. At the time of writing, the official death toll is 151, with 30 people still missing. A total of eleven people have now been arrested in relation to the fire, including two directors of the consultancy firm in charge of the renovation project that was taking place at Wang Fuk Court.

On Chinese social media, the fire has been top-trending news for days. One major point of discussion has been how the fire could have spread so rapidly; what started as a smaller blaze turned into an inferno within minutes. As part of exterior maintenance work, the buildings were covered in bamboo scaffolding and protective netting. Dry weather and strong winds contributed to the rapid spread. Residents said they had repeatedly seen construction workers smoking at the site.

Online conversations initially focused on the bamboo scaffolding, which is traditionally used in construction in Hong Kong for its flexibility and fire resistance. Soon, conversations shifted, blaming the flammable material used in the netting, as well as the styrofoam insulation used to seal windows. Although there are voices speaking out against misinformation regarding the flammability of bamboo, some commenters still point to the bamboo for intensifying the fire and making rescue operations more difficult.

Another issue is the fire system. A former security supervisor alleged the estate’s fire systems were frequently switched off. The claim, reported by local media, has intensified scrutiny and public concern over estate safety management.

What stands out in these discussions on the fire is that people are also tying it to deeper-rooted issues in Hong Kong. Since it’s Hong Kong, there’s arguably some more online room for discussion on such a topic. One Weibo blogger named ‘Jinshu Sister’ wrote: “The blaze exposed two very different worlds within ‘glamorous’ (光鲜) Hong Kong: one world is the fast-moving international metropolis, a playground for capital and elites. The other world consists of citizens living in decades-old buildings. Their hopes of improving their housing have been repeatedly delayed due to practical difficulties, such as costly maintenance fees and the complicated procedures of owners’ corporations. A truly great city is not defined by how many world-class skyscrapers it has, but by whether it can protect the life and safety of every ordinary person living in it.”

2. Living Together Now Counts as “Family Members”

Image by state media outlet CNR: “Living together before marriage is also belongs to [the category of] family members.”

The move is meant to protect victims of domestic abuse and help prosecute abusers within the context of the Anti-Domestic Violence Law. Forms of abuse beyond physical injury (e.g. mental abuse) will also be recognized as domestic violence.

The announcement has sparked heated debates as people began worrying about their current relationships being legally defined as a de facto marriage, with various implications regarding spousal obligations, property rights, and financial issues — including concerns that partners might suddenly be treated as legally responsible for each other’s debts. In recent years, there have been increasing discussions about women marrying to shift their personal debts onto their husbands (there’s even a word for it).

But legal experts on social media say there’s no need to panic: people still need to be legally married to be designated as an official married couple, with all marital obligations and benefits. They emphasize that the current revision is mainly meant to standardize the handling of domestic violence cases nationwide — especially at a time when more young Chinese are delaying marriage and choosing to live together. In the past, there have been cases of men severely abusing their live-in girlfriends, but because they were not legally married, such incidents were treated merely as “ordinary disputes among citizens.”

In light of the many trending stories over the past years concerning domestic violence, you might expect more support for this legal revision. However, people have doubts about how cohabitation will actually be defined in court. One commenter on Weibo wrote: “How should it be defined? If you have sex once a week, is that considered cohabitation? If you stay together for one week every month, is that considered cohabitation? If you have long-term sexual relations but leave after it’s over and don’t sleep together at night, is that cohabitation? There is only one answer: discretionary power (自由裁量权). If the judge says it is cohabitation, then it is cohabitation. Since cohabitation makes you ‘family members,’ can the other party then take half of the house?”

3. Japanese Concerts in China Hit by Sino-Japanese Tensions

Over the past weekend, video footage showing how a concert by Japanese artist Maki Otsuki was suddenly and quite dramatically stopped while she was singing on stage — the lights were turned off, her mic was taken away, and she was escorted off — popped up all over WeChat and beyond (see video on X), followed by various write-ups on the incident, which were soon taken offline.

Ayumi Hamasaki, another famous Japanese artist, also saw her Shanghai concert — 14,000 tickets sold — canceled just a day before the show. Although there was not a single audience member, she performed anyway, leaving her performing alone in an empty venue. She posted about it herself (see photos), expressing sadness over the elaborate stage setup prepared by 200 staff members over several days that now had to be dismantled without the concert ever taking place.

The “lights out” moment for Otsuki, Hamasaki, and many other Japanese artists and musicians in China was attributed to “force majeure” (因不可抗力) in venue statements coming from Beijing, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, and beyond. It comes amid heightened tensions between Japan and China following Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s November 7 remarks suggesting that Chinese actions regarding Taiwan could prompt a military defense response from Tokyo, which infuriated China for “intervening in China’s sovereignty” and has been an ongoing major topic ever since.

On December 1, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian responded to questions about the cancellations during a regular press briefing by saying that reporters should inquire with the Chinese organizers of these events instead — providing no comments on the official reasons behind the wave of abrupt cancellations, which appear to have stemmed from a sweeping directive from Chinese authorities to halt Japanese cultural events.

It’s not only the music and event industry that’s been affected by recent escalations. Chinese airlines have sharply reduced flights to Japan in December, and Japanese movie releases in China have been postponed as well.

There have been mixed reactions following the wave of cancellations. Despite anti-Japanese sentiments online, many people also feel this move unfairly impacts Chinese companies and consumers. Political commentator Hu Xijin addressed the issue, writing: “First, this demonstrates China’s resolve to strengthen sanctions against Japan by cancelling performances by Japanese artists coming to China, and that certainly generates a positive effect. But at the same time, Chinese performance companies will face costs from breaching contracts and from the upfront investments already made; the city of Shanghai and its transportation sector lose a piece of consumption; some audience members who had already traveled from other places to Shanghai are left with nothing; and many ticket holders, especially those who planned to travel from other cities, had their weekend plans disrupted. Taken together, all of these are losses on China’s side.”

Returning to China next week [下周回国] (xià zhōu huíguó)

“Returning to China next week” has been a popular phrase for years in relation to tech entrepreneur Jia Yueting (贾跃亭), who departed China during the 2017 collapse of his LeEco tech company, leaving behind billions in debt.

While going on to found and lead EV startup Faraday Future (FF) in California, Jia repeatedly told Chinese audiences that he would return “next week.” When next week became next month, next year, and eventually never, “returning to China next week” became a running joke on social media, representing big promises with zero follow-up.

Now, Jia has again made headlines after announcing ambitious new plans for the future of FF and autonomous driving. Not only does Jia intend to cooperate with Tesla, he also said that FF and FX (the company’s second brand targeted at the mass market) have a five-year sales target of 500,000 cars. FF’s technology partner AIXC is the newly listed AI x Crypto company that is supposed to shake up the market. Jia’s business strategy has apparently pivoted to trying to create a tech + AI + crypto ecosystem in which each business strengthens the other.

Jia’s latest plans add to the series of grandiose promises that have made him a recurring character in Chinese online discussions. Although often mocked, there is also fascination in how Jia continues to stay in the headlines and attract new investments, seemingly without end.

Of course, after all this, netizens still wonder: “But will he still return to China next week?”

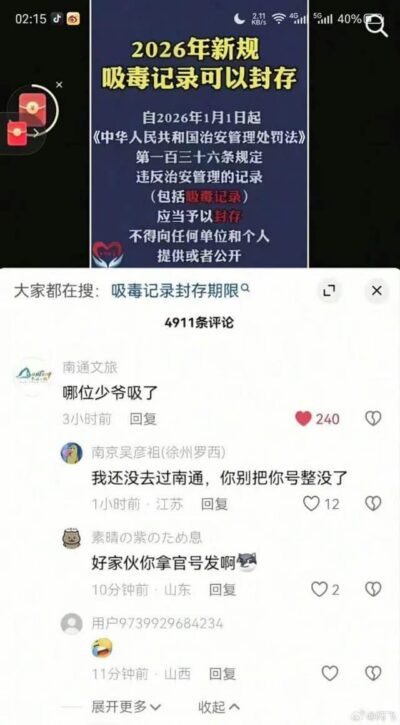

A screenshot showing a cheeky comment from an unexpected account has gone mega viral this week. The comment was made on Douyin by an official local government account in relation to a new law on sealing minor-offence records.

The revised section of the Public Security Administration Law, taking effect on January 1, 2026, adds the possibility of sealing certain administrative violations. Online, people mostly connected this to drug-related offences, wondering whether it would allow people whose names are tied to drug-related penalties to now have their records sealed.

Under a social media post about this issue, the official account of Nantong’s Culture & Tourism Bureau replied: “Which young master was caught using [drugs]?”(“哪位少爷吸了”), jokingly suggesting that the law has been introduced to protect certain individuals from powerful families.

The edgy remark sent the Nantong Tourism Bureau account’s followers up by nearly 1.5 million overnight, eventually adding a total of around 4 million new fans. And although the comment was soon deleted, it has boosted the visibility of Nantong, with some supporters suggesting that if its cultural bureau dares to make such bold remarks, the city itself might be worth a visit.

The moment shows that it only takes a tiny comment to go viral, and that, perhaps, Nantong now has a job opening for a new social media manager to entertain their millions of new followers with content that’s a bit less edgy.😅

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China China Trend Watch. For slower-moving trends and deeper structural analysis, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

If you happen to be reading this without a paid subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

Household notice: if you are receiving duplicate issues of this newsletter in your inbox, you are probably subscribed on both the main site and the Substack platform. For your own convenience, you can unsubscribe from one of them (let me know if you need help with that).

Many thanks and credits to Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang for helping curate the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or

email me. First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

Why Were 100,000 Pregnant Women’s Blood Samples Smuggled Out of China?

When an Entertainment Scandal Gets Political: How Wong Kar-wai Survived a Nationalist Storm

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment6 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment6 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital12 months ago

China Digital12 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

Tom

May 7, 2023 at 8:10 pm

Reminded me somehow of the 1964 JP Belmondo movie L’homme de Rio, minus the narcissistic component of today. Or would these youngsters do these trips, this (IMO boring) gamification of travel, if they had no way of bragging about it? An honest question, to a degree, because I seriously don’t care what they do.