China Insight

Critical Essay: “The Hype Surrounding Zibo BBQ is a Sign of Social Wasteland”

The essay suggests that the recent popularity of Zibo BBQ is a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and empty social spectacle.

Published

1 year agoon

Fast, fun, BBQ travel is a major topic on Chinese social media these days. One WeChat essay recently attracted attention for arguing that the hype surrounding Zibo barbecue is a symptom of a “sick society” in which people are disconnected from meaningful topics. While serious social issues are muted and superficial marketing tricks are blasted all over the internet, China’s “hypocritical youth” actively participate in the societal emptiness they say they reject.

Everyone is talking about Zibo. The old industrial city in Shandong suddenly became the hottest city in China earlier this year when big groups of young people hopped on trains to seize the post-Covid travel opportunity and enjoy a BBQ-filled weekend.

As described in our previous article on Zibo, the town achieved hit status through a combination of factors: its appealing local barbecue culture, the city’s hospitality to students in difficult zero Covid times, the 2023 spring travel craze, smart city marketing, and the social media trends surrounding Zibo which further fueled the hype.

The Zibo BBQ craze. Image via 163.com.

Ever since April and throughout this Labor Day holiday, Zibo managed to crawl into Chinese social media’s top trending lists on a daily basis. And now Zibo has also become part of a bigger travel trend by Chinese younger generations that is all about fast, frugal fun (read here).

But despite all the videos showing BBQ parties, travel excitement, and smiling visitors, the Zibo hype is not all about roses, and there are also voices criticizing the craze.

One of these voices is that of the author of a recent article titled “The Hype Surrounding Zibo BBQ is a Sign of Social Wasteland” (“淄博烧烤走红是社会荒芜的表现”), which was posted by Chinese Professor of Journalism and Communication Liu Yadong (刘亚东).

Liu Yadong is a senior journalist and former editor-in-chief of Science and Technology Daily (科技日报). He is now a professor at Nankai University and the Dean of School of Journalism and Communication.

Although the article is attributed to Liu in most Weibo discussions, the article originally appeared on the WeChat account Jiuwenpinglun (旧闻评论), authored by ‘Picture-Taking Master Song’ (照相的宋师傅), pen name of prominent Chinese journalist Song Zhibiao (宋志标).

The article includes some hot takes on China’s recently hyped Zibo travel culture, which is strongly connected to social media governance and city marketing initiatives. The aurthor argues that the Zibo craze is a symbol of “societal illness” that uses temporary hypes, facilitated by social media, to cover up existing problems and, most of all, is a sign of a society that is devoid of true value.

It also criticizes those netizens/young people that jump in on the hype. Despite claiming to go against various top-down policies, they willingly and collectively are driving the hypes that are supposedly also part of dynamics that are strategically used by those in power to maintain influence.

Here, we provide a full translation of the short essay, translated by What’s on Weibo. Some parts are loosely translated or slightly edited for clarity, the Chinese original is included for your reference.

“The Hype Surrounding Zibo BBQ is a Sign of Social Wasteland” [TRANSLATION]

“Zibo barbecue has gone viral overnight, and with giant steps, we’re seeing a preposterous scene unfold: crowds of people are flocking to Zibo, long lines are forming in front of the BBQ stalls, the municipal government is making emergency preparations in various ways to facilitate “two-way travel” for young people coming to the city. This immersive scene is unfolding at the barbecue grills, while we are seeing Zibo’s ‘northeasternisation’ (东北化)* and the accelerated desolation of society. *[‘Dongbei-ization’ or ‘northeasterisation’ is a term used to refer to the phenomenon where people are leaving the northeastern provinces of China and moving to other provinces or regions which are then ‘northeasternized.’]

This desolation of society does not refer to a lack of people or empty streets. On the contrary, the contemporary social wasteland is crowded, grimy, and lively. The youth, in particular, are unconsciously marching in the same direction, and with fervor, they are chewing on Zibo BBQ ‘soul food’ as if they were devouring their own souls. In this existence, we are witnessing the demise of certain parts of themselves and our own.

Many people really want to explore the reasons why Zibo became such a hype, and they can list various factors, but they all stay at the instrumental level and do not go beyond it. This kind of result of up-and-down marketing of [China’s] cultural tourism industry is not so much because of collusion between local officials and traffic-generating mechanisms, as it is a random and hollow expression of society’s desolation. Society is sick, and the hyping of things like barbecue is just a symptom of that.”

淄博烧烤一夜走红,正在大踏步铺陈一副荒诞景象:成群结队的外地人蜂拥前往,烧烤摊前排满长队,市政府正在从各个方面应急建设,以奠基淄博与年轻人的“双向奔赴”。这是发生在烧烤架边上的沉浸式场景,淄博东北化,而社会加速荒芜化。

这里的社会荒芜并不是指人流量稀少,或街面荒凉,相反,现在的社会荒芜群集、油腻且热闹,尤其是年轻的躯壳无意识地追求整齐划一的动作,以饱满的热情,像吞噬自己灵魂一样咀嚼淄博烧烤的“灵魂三件套”。这样的存在,见证了自己和他人某些部分的死亡。

有人很想探究淄博烧烤走红的成因,罗列各种因素,但都停留在工具的层面,而没有往前更推进一步。这种文旅行业乍起乍落的营销成果,与其说是主政者与流量制造机制的合谋,莫若说是社会荒芜化随机的、空洞的表现。社会病了,烧烤等走红是它的症状。”

“It’s especially the young people that are unconsciously moving in the same direction and, full of enthusiasm, they are chewing on Zibo BBQ ‘soul food’ as if they were devouring their own souls.”

“Pulling stunts like turning barbecue into an online sensation and tourism bureau directors dressing up etc., help places to be covered by a huge filter, and it enables local authorities’ supervisory departments to shift their cultural and creative thinking to the short video era. One of the characteristics of the short video era is the shrewd operation that appears to conform to the lifestyle of the lower classes, grabbing their attention and using large-scale deception to cover up the rapid social barrenness of everyday life.

In this everyday life, a large number of more valuable topics are first decoupled from power, and then detached from the people closely related to them. In this process, these meaningful topics receive blows from two directions: firstly they are restrained and smeared by authorities, and then they are ridiculed and abandoned by the public. The erosion of our basis of values is similar to the process of desertification, and it is achieved through manipulation and conformation.

It seems that we can’t regard the people in this social wasteland purely as tools. They happily laugh in front of the barbecue stalls, they skillfully jumble up words and use special characters on social media to be influenced and influence others. For a moment, they forget about the ubiquitous risk of unemployment, and without a sense of history or awareness of problems, they fantasize about the next paradise.

The satirical thing is that while the young generation prides itself in ‘lying flat’ and in rejecting the policy lines [that encourage them] to have more kids, struggle, buy houses, etc, they vigorously participate in a movement to create a landscape of social desolation. The social wasteland provides them with a life kit where one thing after the next comes dashing up and then speeds away. This makes the wastage of the hypocritical youth especially evident, and because they are overly exploited, they are particularly ill.”

“烧烤网红、文旅局长便装等把戏,让一个地方罩上巨大的滤镜,帮助当局的主管部门从文创思维过渡到视频时代。短视频时代的特征之一,就是以名义上附和底层生活方式的精明操作,收割底层的注意力,以规模化的欺骗掩盖社会急速荒芜的日常。

在这种社会日常中,大量更有价值的议题先是与权力脱钩,再与和议题密切相关的人群脱钩。脱钩过程,价值议题遭到了两个方向的捶打:先是被权力遏制与污化,然后再受到民众的嘲笑与抛弃。价值基础的流失近似荒漠化进程,在操作与附和中达致。

似乎还不能将荒芜社会中人视作完全的工具人,他们在烧烤摊前发出快乐的笑声,他们娴熟地使用掺杂字母、异形字的话术在社交媒体上接承接灌输并灌输别人。一时间,他们忘了四面楚歌的失业风险,没有历史感与问题意识,却在畅想下一个乐园。

讽刺的是,年轻世代一边以躺平自诩,排斥多生、奋斗、买房等政策口径,另一边却精力旺盛地参与社会荒芜化的造景运动。社会荒芜提供了一个个飞奔而来又疾驰而去的生活套件,这让虚伪的年轻人损耗尤其明显,也因为被过度地利用,他们病得特别厉害。

“The people in this social wasteland aren’t just tools as they happily laugh in front of the barbecue stalls. For a moment, they forget about the risk of unemployment, and without a sense of history or awareness of problems, they fantasize about the next paradise.”

“The short video and click-through economy originated on the internet, and with the aid of the social wasteland, they have given birth to plastic flower-like gardens. The official attitude is very straightforward. On the one hand, they tame the flow of serious topics, directing and filtering their moral assessment; and on the other hand, they utilize it [the short video & click-through economy] to their advantage, harnessing the power of traffic to soften underlying anxieties.

Recently, cultural tourism chiefs in all parts of the country, according to the symbols of their local culture, competed with each other in [online] costume shows put together due to safe traffic flows.* These costume shows, realized for the sake of clicks, ended up straight in the social corner of topics such as the Zibo BBQ stalls – because there are no social topics to compete with, – and similarly resonated with spirit-lacking audiences. *[for more information on this trend, see our article about the cultural tourism chief video hype here.]

The “Zibo BBQ hype” and the trend of “cultural tourism chiefs costume” may appear as noteworthy accomplishments for cultural tourism bureaus, but the growth of such “light industry” is insufficient in addressing real issues, let alone the ongoing financial crisis affecting different regions. It is ineffectual in resolving the predicaments of economic development. While it is hailed in a desolate society, it may only serve as a temporary distraction, numbing the senses and blinding people from reality.

In the process of society becoming more desolate, the concept of “yān huǒ qì” (烟火气)* is almost destined to be emphasized, and it carries a feeling of nationalism and forlorn. Its visual effect is quite impressive, providing the illusion for both young and old in a desolate society, while dulling the strict street order enforced by the city police, giving people a feeling of intoxication. With the twinkling of the neon lights and the smoke filling up the air, the world can be anything.

*[Yān huǒ qì is a 2022 buzzword, initially means the smoke and fire produced from cooking food, but after ‘zero Covid,’ the phrase has come to be used to capture how restaurants and the hospitality sector across China seeing vitality again.]

Not long ago, ‘yān huǒ qì’ was a rhetoric to decorate the facade of the controlled economy, but now its existence has become like a common understanding between the government and the people. This rhetorical resonance, recited from above and echoed from below, has unexpectedly masked the perspective the term ‘yān huǒ qì’ represents, [namely that of] those in power overseeing it.”

“短视频及流量经济是局域网的原创,它们借助社会荒芜衍生出塑料花一样的花园。官方的取态非常干脆,它一方面驯化严肃议题的流量呈现,引导阻击它的道德评价;另一方面,它又滥用“为我所用”的原则攫取流量利益,以柔化深层次的焦虑。

前段时间,各地文旅局长按照当地的标志性文化,竞相登上由到安全流量组装而成的变装秀场。这些冲着流量变现而去的变装秀,因为没有与之竞的争社会议题,它们长驱直入到类似“淄博烧烤摊”的社会角落,与精神贫乏的受众同频共振。

“淄博烧烤走红”,“文旅局长变装”也许可作为文旅局的业绩,但这种“轻工业”的繁荣无法求解真问题,丝毫不减席卷各地的财政危机,更无助于解决经济发展的困境。当然,它们在荒芜社会空间搞出几声官民合唱,兴许可以暂时麻醉神经,遮断望眼。

在社会荒芜化的进程中,“烟火气”这个词得以强调几乎是命中注定,带着某种民族性与悲凉感。它的视觉效果相当可观,为荒芜社会提供了老少皆宜的幻觉,同时钝化了城管严控的街头秩序,令人们获得醉酒般的感受,假如霓虹闪烁,缭绕烟雾,亦可人间万象。

在不久之前,“烟火气”还是装点管控经济门面的修辞,现如今成为官民共识一样的存在。这种上有念叨、下有回声的修辞共鸣,出人意料地掩盖了“烟火气”这个词所象征的权力俯瞰视角,社会的荒芜化不仅蚕食价值议题,也以不知畏惧的憨态吞噬阶级差异。

“Have you considered that the desolation of society does not necessarily make it safer? In fact, it may just be another extreme form of a risky society. It is only ignored because the script of click-through traffic plays around the clock.”

“Similar to the intensity of a desert storm, the attention span of a desolate society is also brief, and the pace of the attention economy is fast. In a desolate society, the density of life for its members is low, and they can bear with or ignore their quality of life, but they cannot endure a short-lived infatuation. As the Zibo barbecue hype gained momentum, the countdown to the conclusion of the Ding Zhen craze* had already commenced. *[read about the hype surrounding Ding Zhen here.]

Some people believe that eliminating social diversity will also eliminate certain unpopular hidden dangers. However, have you considered that the desolation of society does not necessarily make it safer? In fact, it may just be another extreme form of a risky society that is ignored because the script of click-through traffic keeps playing around the clock. While you can control the click-through traffic, the logic of a decaying society remains uncontrollable.

Ultimately, the Zibo barbecue hype is very boring. It offers little solace to the government’s concerns about development or the public’s pressures for survival, unless we define a drunken and reckless lifestyle as positive. While we cannot fully blame the click-through economy for the desolation of society, it does contribute to numbing society’s awareness of how it operates, and the warning signs of a hollow society are all around us”.

“就像沙漠上的风暴特别强,荒芜社会的注意力也相当有限,注意力经济快速来也会快速去,毕竟荒芜意味着社会成员的生活密度低,他们可以容忍或漠视生活质量,但无法容忍略微时长的钟情。就在淄博烧烤走红的同时,始乱终弃的丁真式命结局就开始倒计时。

有人以为,消除了社会的多元化,就可以消除某些不受待见的隐患。何曾想,社会的荒芜化并不与安全社会划等号,它是风险社会的极端形式之一,只因日夜不停上演的流量剧本被忽视了。流量或许可以驯服,但社会荒芜化却沿着它的逻辑如脱缰之马。

说到底,淄博烧烤走红是非常无聊的事,它既不能真正安慰官方的发展焦虑,也无法减轻大众的生存压力,除非醉生梦死也被定义为积极的生活方式。当然,流量无法为社会的荒芜化负上全部责任,但它在合谋中钝化社会敏感度也是事实,荒芜将警讯紧紧包裹。”

Online Responses

The short essay is a critique of China’s youth, the online media sphere, and the click culture that goes from one hype to the next. But it is also a serious critique of Chinese authorities and the dynamics in place to mute serious social issues while blasting superficial trends.

The author suggests that everything is becoming less diverse (places like Zibo are ‘northeasternized’) and that society is actually so empty that people are constantly trying to fill the holes of their attention with the next meaningless buzz. Besides Zibo BBQ (link), he also mentions the Cultural Tourism chief cosplay trend (link), and the sudden rise to fame of Ding Zhen (link).

With Zibo and other domestic travel destinations being such a hot topic on Chinese social media recently, Liu’s critical essay – published on WeChat account Jiuwen Pinglun 旧闻评论 on April 17 – has inevitably become a topic of discussion.

By now, the essay has been deleted from Weixin, but online screenshots are still circulating online and have triggered new discussions this Labor Day holiday week (this link and this ifeng link are also still active). Various Weibo threads on the essay received hundreds of likes and comments over the past two days.

Some bloggers on Weibo value Liu’s perspective. As one blogger (@校长梁山) writes: “This is a thoughtful and high-quality article that you rarely come across (..) I have no intention of criticizing the government, but in terms of social management, the views in this article are worth thinking about.”

“Actually, he is right,” another commenter writes: “What he’s expressing is that the current economic downfall cannot be solved by the next barbecue hype, but this is something the media is burying” (the idiom used is yǎn ěr dào líng 掩耳盗铃, meaning covering one’s ears while stealing a bell, burying one’s head in the sand).” Those agreeing with the author suggest that Zibo’s success might be a win for its local cultural tourism department, but actually says nothing about a recovery of other industries and economy at large.

But there are also those who think Liu’s perspective is outdated and that, while talking about a lack of meaning, his own words are actually meaningless: “I have no idea what he is talking about.”

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Some say he is making a big fuss over nothing, suggesting that it is only normal for people to want to seek for entertainment and simple pleasures like eating BBQ skwers, and that it does not represent a bigger problem at all. He is “moaning over an imaginary illness,” one Weibo user wrote (“wú bìng shēn yín” 无病呻吟).

Content deleted on WeChat.

Although not everyone agrees with Liu’s takes, many do agree that it gives food for thought. However, the deletion of the essay itself and the removal of some related online comment threads also prevents further discussions on the topic, which ironically exemplifies one of the issues that the author aimed to address in his essay.

By Manya Koetse

Edited May 19, 2023: An earlier version of this article suggested Liu Yadong (刘亚东) is the original author of the critical essay. Although the article is attributed to Liu on Chinese social media, Liu reposted it and had his own bio under the article, but the original (censored) article is authored by Song Zhibao (宋志标).

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Insight

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

The story of ‘Fat Cat’ has become a hot topic in China, sparking widespread sympathy and discussions online.

Published

3 months agoon

May 9, 2024

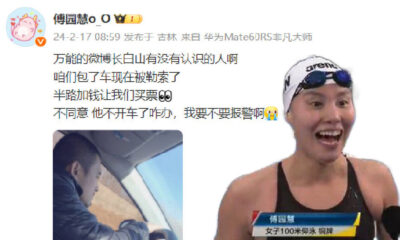

The tragic story behind the recent suicide of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ has become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media, touching upon broader societal issues from unfair gender dynamics to businesses taking advantage of grieving internet users.

The story of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer from Hunan who committed suicide has gone completely viral on Weibo and beyond this week, generating many discussions.

In late April of this year, the young man nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ (胖猫 Pàng Māo, literally fat or chubby cat), tragically ended his life by jumping into the river near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge (重庆长江大桥) following a breakup with his girlfriend. By now, the incident has come to be known as the “Fat Cat Jumping Into the River Incident” (胖猫跳江事件).

News of his suicide soon made its rounds on the internet, and some bloggers started looking into what was behind the story. The man’s sister also spoke out through online channels, and numerous chat records between the young man and his girlfriend emerged online.

One aspect of his story that gained traction in early May is the revelation that the man had invested all his resources into the relationship. Allegedly, he made significant financial sacrifices, giving his girlfriend over 510,000 RMB (approximately 71,000 USD) throughout their relationship, in a time frame of two years.

When his girlfriend ended the relationship, despite all of his efforts, he was devastated and took his own life.

The story was picked up by various Chinese media outlets, and prominent social and political commentator Hu Xijin also wrote a post about Fat Cat, stating the sad story had made him tear up.

As the news spread, it sparked a multitude of hashtags on Weibo, with thousands of netizens pouring out their thoughts and emotions in response to the story.

Playing Games for Love

The main part of this story that is triggering online discussions is how ‘Fat Cat,’ a young man who possessed virtually nothing, managed to provide his girlfriend, who was six years older, with such a significant amount of money – and why he was willing to sacrifice so much in order to do so.

The young man reportedly was able to make money by playing video games, specifically by being a so-called ‘booster’ by playing with others and helping them get to a higher level in multiplayer online battle games.

According to his sister, he started working as a ‘professional’ video gamer as a means of generating money to satisfy his girlfriend, who allegedly always demanded more.

He registered a total of 36 accounts to receive orders to play online games, making 20 yuan per game (about $2.80). Because this consumed all of his time, he barely went out anymore and his social life was dead.

In order to save more money, he tried to keep his own expenses as low as possible, and would only get takeout food for himself for no more than 10 yuan ($1,4). His online avatar was an image of a cat saying “I don’t want to eat vegetables, I want to eat McDonald’s.”

The woman in question who he made so many sacrifices for is named Tan Zhu (谭竹), and she soon became the topic of public scrutiny. In one screenshot of a chat conversation between Tan and her boyfriend that leaked online, she claimed she needed money for various things. The two had agreed to get married later in this year.

Despite of this, she still broke up with him, driving him to jump off the bridge after transferring his remaining 66,000 RMB (9135 USD) to Tan Zhu.

As the story fermented online, Tan Zhu also shared her side of the story. She claimed that she had met ‘Fat Cat’ over two years ago through online gaming and had started a long distance relationship with him. They had actually only met up twice before he moved to Chongqing. She emphasized that financial gain was never a motivating factor in their relationship.

Tan additionally asserted that she had previously repaid 130,000 RMB (18,000 USD) to him and that they had reached a settlement agreement shortly before his tragic death.

Ordering Take-Out to Mourn Fat Cat

– “I hope you rest in peace.”

– “Little fat cat, I hope you’ll be less foolish in your next life.”

– “In your next life, love yourself first.”

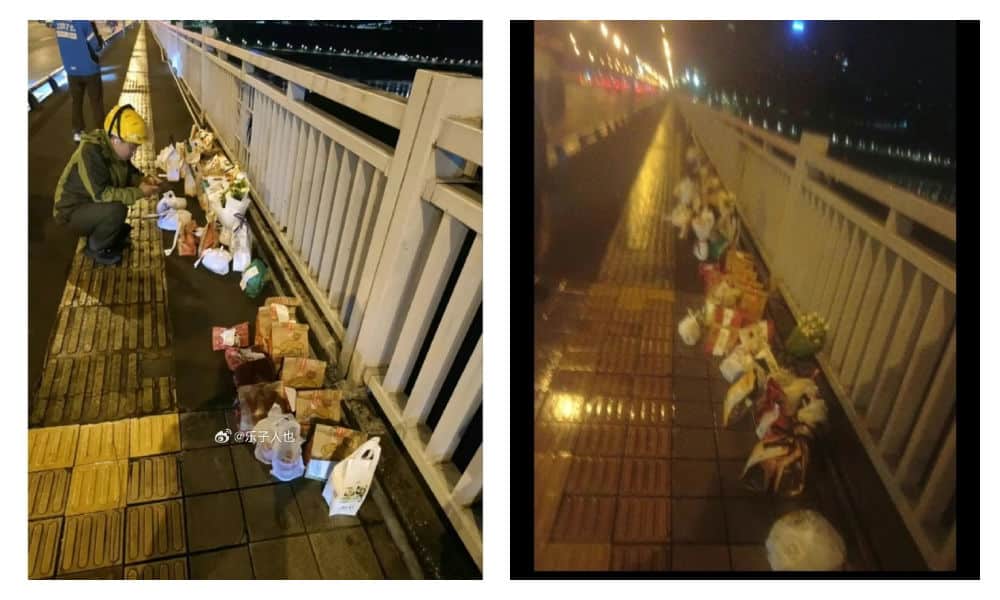

These are just a few of the messages left by netizens on notes attached to takeout food deliveries near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge.

AI-generated image spread on Chinese social media in connection to the event.

As Fat Cat’s story stirred up significant online discussion, with many expressing sympathy for the young man who rarely indulged in spending on food and drinks, some internet users took the step of ordering McDonalds and other food delivery services to the bridge, where he tragically jumped from, in his honor.

This soon snowballed into more people ordering food and drinks to the bridge, resulting in a constant flow of delivery staff and a pile-up of take-out bags.

Delivery food on the bridge, photo via Weibo.

However, as the food delivery efforts picked up pace, it came to light that some of the deliveries ordered and paid for were either empty or contained something different; certain restaurants, aware of the collective effort to honor the young man, deliberately left the food boxes empty or substituted sodas or tea with tap water.

At least five restaurants were caught not delivering the actual orders. Chinese bubble tea shop ChaPanda was exposed for substituting water for milk tea in their cups. On May 3rd, ChaPanda responded that they had fired the responsible employee.

Another store, the Zhu Xiaoxiao Luosifen (朱小小螺蛳粉), responded on that they had temporarily closed the shop in question to deal with the issue. Chinese fast food chain NewYobo (牛约堡) also acknowledged that at least twenty orders they received were incomplete.

Fast food company Wallace (华莱士) responded to the controversy by stating they had dismissed the employees involved. Mixue Ice Cream & Tea (蜜雪冰城) issued an apology and temporarily closed one of their stores implicated in delivering empty orders.

In the midst of all the controversy, Fat Cat’s sister asked internet users to refrain from ordering take-out food as a means of mourning and honoring her brother.

Nevertheless, take-out food and flowers continued to accumulate near the bridge, prompting local authorities to think of ways of how to deal with this unique method of honoring the deceased gamer.

Gamer Boy Meets Girl

On Chinese social media, this story has also become a topic of debate in the context of gender dynamics and social inequality.

There are some male bloggers who are angry with Tan Zhu, suggesting her behaviour is an example of everything that’s supposedly “wrong” with Chinese women in this day and age.

Others place blame on Fat Cat for believing that he could buy love and maintain a relationship through financial means. This irked some feminist bloggers, who see it as a chauvinistic attitude towards women.

A main, recurring idea in these discussions is that young Chinese men such as Fat Cat, who are at the low end of the social ladder, are actually particularly vulnerable in a fiercely competitive society. Here, a gender imbalance and surplus of unmarried men make it easier for women to potentially exploit those desperate for companionship.

The story of Fat Cat brings back memories of ‘Mo Cha Official,’ a not-so-famous blogger who gained posthumous fame in 2021 when details of his unhappy life surfaced online.

Likewise, the tragic tale of WePhone founder Su Xiangmao (苏享茂) resurfaces. In 2017, the 37-year-old IT entrepreneur from Beijing took his own life, leaving behind a note alleging blackmail by his 29-year-old ex-wife, who demanded 10 million RMB (±1.5 million USD) (read story).

Another aspect of this viral story that is mentioned by netizens is how it gained so much attention during the Chinese May holidays, coinciding with the tragic news of the southern China highway collapse in Guangdong. That major incident resulted in the deaths of at least 48 people, and triggered questions over road safety and flawed construction designs. Some speculate that the prominence given to the Fat Cat story on trending topic lists may have been a deliberate attempt to divert attention away from this incident.

‘Fat Cat’ was cremated. His family stated their intention to take necessary legal steps to recover the money from his former girlfriend, but Tan Zhu reportedly already reached an agreement with the father and settled the case. Nevertheless, the case continues to generate discussions online, with some people wondering: “Is it over yet? Can we talk about something different now?”

Fat Cat images projected in Times Square

However, given that images of the ‘Fat Cat’ avatar have even appeared in Times Square in New York by now (Chinese internet users projected it on one of the big LED screens), it’s likely that this story will be remembered and talked about for some time to come.

UPDATE MAY 25

On May 20, local authorities issued a lengthy report to clarify the timeline of events and details surrounding the death of “Fat Cat,” which had attracted significant attention across China.

The report concluded that there was no fraud involved and that “Fat Cat” and his girlfriend were in a genuine relationship. Tan did not deceive “Fat Cat” for money; the transfers were voluntary. Furthermore, Tan returned most of the money to his parents.

The gamer’s sister is reportedly still being investigated for potentially infringing on Tan’s privacy by disclosing numerous private details to the public.

In the end, one thing is clear in this gamer’s tragic story, which is that there are no winners.

By Manya Koetse

– With contributions by Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

3 months agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

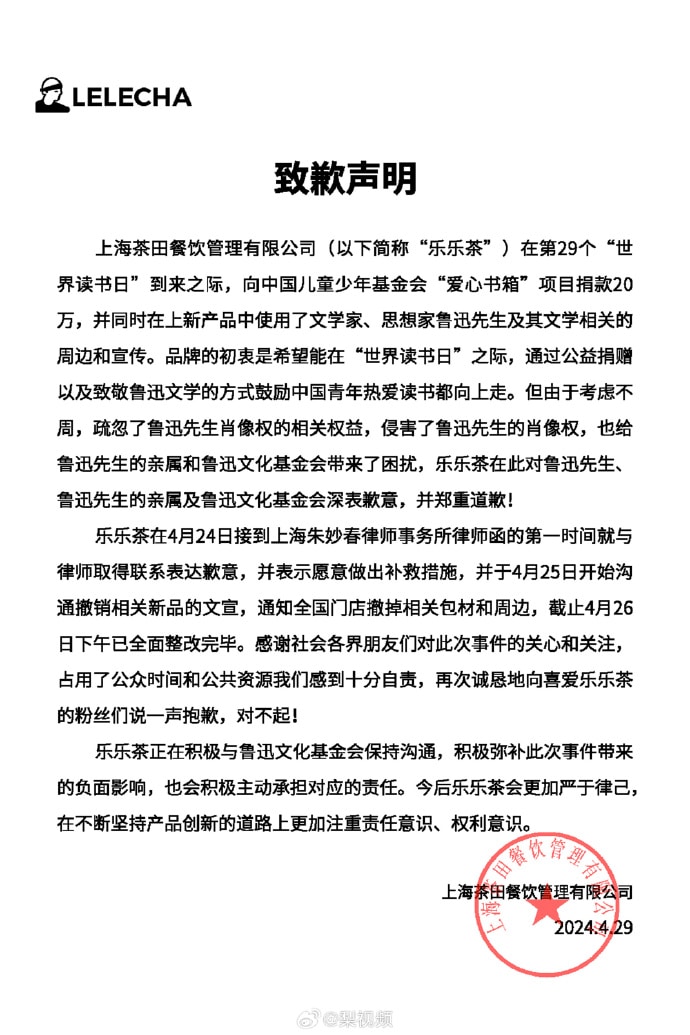

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

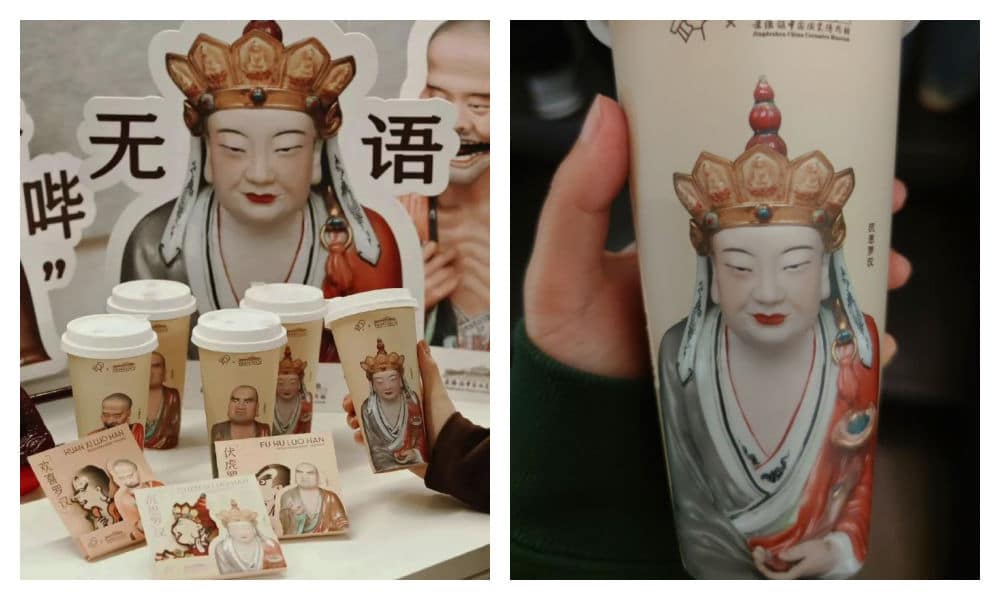

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?