China Media

The Russia-Ukraine War in Chinese Online Media (LAC Short)

A shifting focus on other issues that are framed within Chinese news narratives of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Published

4 years agoon

As the Russian-Ukraine conflict shows no signs of de-escalation and over two million people have now fled Ukraine, there is a heightened international media focus on Chinese responses to the war.

While the developments in Ukraine are a major topic in Chinese newspapers, on its social media sites, and in its press briefings, the Russia-Ukrainian war – which is commonly referred to as Russia’s “special military operation” – is placed within a specific Chinese narrative.

Recent themes surrounding the Russia-Ukraine conflict in Chinese online media show how the war is framed by news outlets and bloggers when it comes to China’s role in it, shifting the narrative from Beijing’s responsibility to Washington’s irresponsibility.

Within that news narrative, emphasis is placed on the role of the United States, its Western allies, and Chinese resistance against the ‘Cold War mentality’ that allegedly fueled the current crisis. Some themes are recurring in the Chinese media, where today’s violent conflict in Ukraine is also used to reflect on the past and future of China-West relations. In light of the recent developments, NATO’s bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade (1999) became a topic of focus again, together with discussions on what the Ukraine war could mean for Taiwan. In this article, we will explore some of the trends dominating Chinese media discussions within the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“NATO Owes Blood Debt to China”

On February 24th, when people around the world were closely following the latest developments of Russia’s full-scale assault on Ukraine, two hashtags went trending on Chinese social media: “The NATO Still Owes Blood Debt to China” (#北约至今还欠中国一笔血债#) and “The US is Not Qualified to Tell China How to Act” (#美方没资格来告诉中方怎么做#).

These hashtags were promoted on Sina Weibo, one of China’s biggest social media platforms, by state media outlet People’s Daily, receiving over 1.2 billion and 650 million views respectively.

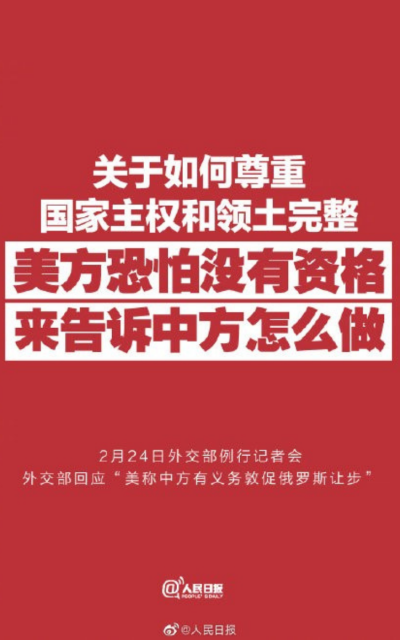

Online poster published by People’s Daily reiterating the words of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson that the United States is not qualified to tell the Chinese side on how to act in light of national sovereignty and territorial integrity (source: People’s Daily, Weibo).

The sentences came up during the February 24th press conference of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in which spokesperson Hua Chunying answered various questions relating to the situation in Ukraine. One of them, posed by a CCTV reporter, referred to comments made by US State Department spokesperson Ned Price, who suggested that China has an obligation to urge Russia to “back down” to de-escalate the situation.

Hua Chunying responded by mentioning China’s recent history of humiliation at the hands of Western powers, saying that “the US is in no position to tell China off.” Hua brought up the 1999 bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia, which killed three Chinese journalists, stating: “NATO still owes the Chinese people a debt of blood.”

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson condemned the United States for its history of continuous overseas military operations and claimed that China still faces “a realistic threat” from the U.S. and its allies today. Joining Western ‘bloc politics’ in condemning Russia is not something China is interested in doing, she concluded. One video of Hua Chunying’s remarks received over two million ‘likes’ on the Weibo platform.

How this specific moment of the press conference was singled out and highlighted by Chinese state media set the tone for the way in which the Russia-Ukraine conflict is framed by official media when it comes to China’s role in it, shifting the narrative from Beijing’s responsibility to Washington’s irresponsibility.

The China Daily frontpage of February 24th literally mentioned how the “irresponsible” United States was “adding fuel to the Ukraine crisis” and accused Washington of aggravating tensions and creating panic on the Ukraine issue. The Jiefang Daily reiterated that same message, meanwhile stressing that China has acted as a responsible leader in avoiding incitement of war (Mo 2022, 1; Liao Qin 2022, 5).

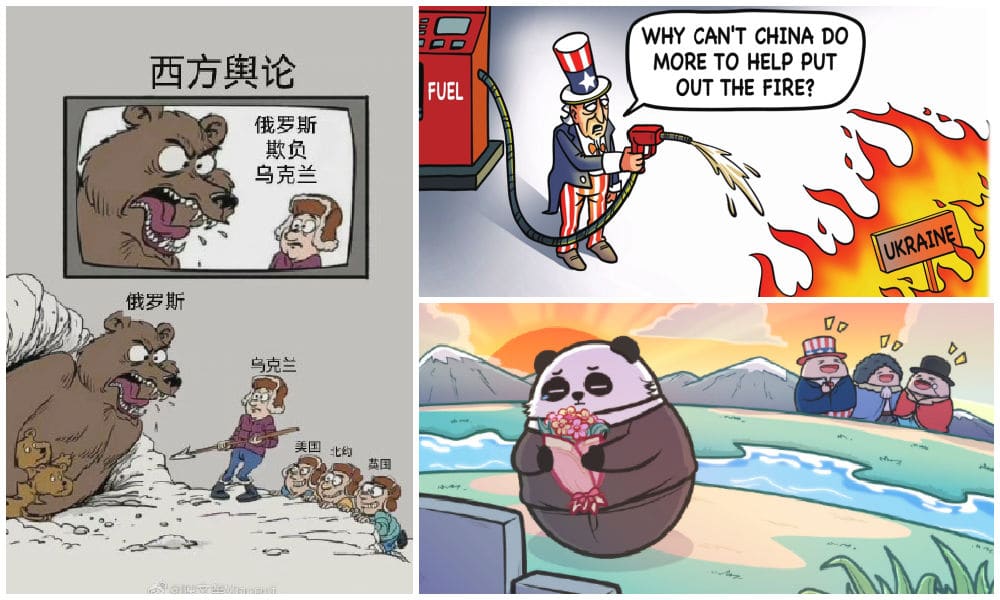

Cartoon published on the English-language site of Chinese state-run media outlet Global Times, by Global Times cartoonist Liu Rui (source link).

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, videos showing footage of the 1999 bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade started circulating online. The influential online news portal Guancha.cn was one of the accounts sharing a short video showing footage of the aftermath of the deadly bombing by the U.S. government, which claimed its intention had been to bomb a Yugoslav arms agency (Parsons & Xu 2001: 51). “We can never forget this day,” Guancha.cn wrote, and soon there were bloggers creating new content on the Belgrade incident explaining why the NATO owed the Chinese people and why the U.S. has no right to pressure China in how to act.

Screenshots from online info sheets explaining “What is NATO’s blood debt to China?” by well-known comic blogger @赛雷三分钟 (link to Weibo source).

This trending topic is telling for how the Russia-Ukraine conflict comes up in Chinese news coverage and on Chinese social media, with many reports and discussions about the situation actually not focusing on what is happening on the ground in Ukraine, but instead focusing on other issues that are framed within Chinese news narratives of the Russia-Ukraine war.

The NATO bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia is one example. The status of Taiwan is another larger recurring topic discussed within the context of the Ukraine conflict.

“Today’s Ukraine, Tomorrow’s Taiwan?”

Soon after the Russian invasion of Ukraine became a reality, Chinese social media users began drawing comparisons between the Taiwan situation and the Ukrainian developments.

“Today’s Ukraine, tomorrow’s Taiwan?” is a phrase that is going around Chinese media a lot these days. On the one hand, many online commenters see the rapid invasion of Ukraine as a warning to Taiwanese that the situation in Taiwan could change within a time frame of just a few days. One meme making its rounds showed a pig called “Taiwan” watching another pig, “Ukraine”, get slaughtered.

A meme circulating on social media shows a pig “Taiwan” watching the slaughtering of another pig “Ukraine.”

Other bloggers see the developments in Ukraine as a warning to mainland Chinese that the West could influence and trigger conflict, and that they could send weapons or provide military support to Taiwan if mainland China would employ force to realize a ‘reunification’ with Taiwan.

Although Chinese authorities have stated that it would be unwise to draw parallels between Ukraine and Taiwan, online conversations comparing the two are ongoing. The search index of Baidu, China’s most popular search engine, clearly shows how web search queries for ‘Taiwan’ peaked at the same time when searches for the term ‘Russia-Ukraine Conflict’ also exploded (see image below).

Baidu Index trend search tool, screenshot via author.

This trend is also fueled by Chinese state media reports about Taiwan. On February 26th, the Global Times news outlet reported that the US Navy destroyer Ralph Johnson was passing through the sensitive Taiwan Strait. Although American officials called the passage “routine” (the warship also sailed through the Taiwan Strait in previous years), the move was presented as a provocative one by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs during a press conference on March 1st.

Following more discussions on Taiwan in the light of Ukraine developments, China Central Television News (CCTV) initiated the hashtag “The Hope for Taiwan’s Future Lies in Achieving National Reunification” (#台湾的前途希望在于实现国家统一#) after Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi addressed the issue during a March 7 press conference.

Although the Ministry of Foreign Affairs once again stressed how Ukraine and Taiwan could not be compared because of Taiwan’s status as “an inalienable part of China’s territory” that will eventually be reunified with the mainland, the address inescapably added to the incorporation of the Ukraine issue into a specific Chinese narrative, triggering more discussions on the differences and similarities between Ukraine’s today and Taiwan’s tomorrow.

“If You’re Anti-War, You Must Be Anti-American”

One other trend that has been clearly visible in Chinese social media discussions regarding the Ukraine conflict is the perceived dichotomy between being ‘anti-war’ and ‘anti-American.’

Although there certainly is public sympathy for the victims of this conflict, Chinese social media is seeing a growing trend of people opposing the anti-war movement, calling them hypocritical and naive for raising their voices to call out this war while they perhaps were not as vocal in condemning other conflicts. According to this reasoning, strong anti-war opponents are labeled as being ‘pro-American.’

One popular science blogger (12+ million followers) on Weibo nicknamed Occam’s Razor (@奥卡姆剃刀) posted a meme (image below) on February 27th, writing:

“Some people are bitterly bashing Russia while self-righteously preaching against the war. Of course, it is correct to be anti-war, and everyone should defend world peace. But you should ask them: were you also anti-war when the United States invaded Iran, Iraq, Panama, Libya, Yugoslavia, or Afghanistan?”

One meme shared on social media, showing a person with “no expression” when the U.S. drops bombs on Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria, Libya, and shouting “I’m Anti-War!!” in the last picture when Russia attacks Ukraine.

The idea that anti-war advocates have a hidden agenda if they are not also speaking out against the United States is visible in countless of posts and videos, not just on Chinese social media site Weibo but also on other popular platforms such as Bilibili and Douyin, where catchy slogans such as “If you’re anti-war but not anti-American, you’re up to no good [you have ulterior motives]” (“反战不反美,心里都有鬼”) and “If you’re anti-war and not anti-American, you are inhumane” (“反战不反美就是反人类”) are ubiquitous.

Over the past years, China’s online media environment has seen several waves of anti-Americanism. In the fall of 2021, China’s epic war movie The Battle at Lake Changjin became a major success. The film, that shows how Chinese troops were severely underestimated by the U.N. forces during the Korean war, came at a time of heightened U.S.-China tensions. According to one of the scriptwriters, the film was supposed to convey that “the Chinese are not to be messed with” (Koetse 2021). It sent out the message that China had to enter the war to fight the ‘imperialist’ United States and its allies as these foreign forces, who looked down on them, would otherwise expand all the way to the doorstep of China and endanger the peaceful development of their newly established nation.

Many Chinese are now also suggesting that the Ukraine conflict is like “China’s Korean War for Russia.” One political cartoon shared on social media titled “Western Public Opinion” shows a zoomed-in image of a big scary bear (“Russia”) and a small, frightened man (“Ukraine”) on a television screen. The scene below shows the full scene, revealing how the small “Ukraine” man, backed by three helpers (“U.S.”, “NATO,” and “Britain”), is poking at the mother bear (“Russia”) who is protecting her cubs in her den.

This adapted cartoon was shared on Weibo, original cartoon is by Pusang Gala and is titled “Narrative vs Reality” (artist page on Facebook).

Online anti-American sentiments are also fueled by Chinese media reports highlighting how other Asian countries supposedly criticize the West and support Russia. When Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan lashed out in response to foreign pressure pushing Pakistan to condemn Russia – asking “What do you think of us? Are we your slaves?” – Chinese media outlet Guancha.cn was quick to turn the topic into a social media hashtag (“Pakistan Asks: Are We a Slave to the West?”). Similarly, the state-run Global Times promoted one of its articles about Indian social media users showing their support for Putin (hashtag: “Great Number of Indian Web Users Strongly Support Russia”).

Meanwhile, the English-language Global Times Twitter account posted a photo of India allegedly lighting up one of its landmark buildings, the Qutub Minar, in support of Russia. The tweet turned out to be misleading, as the Qutub Minar was illuminated on the occasion of Jan Aushadhi Diwas to generate awareness about the usages of generic medicines.

Tweet by Global Times, screenshot by author.

On March 8, as the war between Russia and Ukraine entered day 13, one of the top trending topics on Chinese social media was not the two million people who have fled the war, but the alleged uncovering of 26 U.S. military biological laboratories in Ukraine (hashtag: “The 26 American Biolabs in Ukraine Are Just Tip of Iceberg”).

During a press briefing, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Zhao Lijian expressed concern over the alleged existence of many U.S. biological labs in Ukraine and elsewhere, and questioned the intentions behind running them. According to Bloomberg News, the Chinese accusations of the American military operating ‘dangerous’ biolabs mirrored Russian diversion tactics to justify the Russian invasion. But on Weibo, the topic was viewed over 180 million times within hours and led to countless of comments from Chinese web users condemning the U.S. and demanding answers about the truth behind these biological laboratories.

The Russia-Ukraine war is dominating Chinese online media, without zooming in on what exactly is taking place on the battlegrounds today. In the end, the main framework that Chinese media outlets and bloggers are using to make sense of the Russia-Ukrainian conflict might have much more to do with Beijing’s own strategic ambitions in a changing international community than it has to do with Moscow or Kyiv. Strengthening that news frame is the narrative of China’s painful memories of humiliation at the hands of the very same Western powers that are now trying to get China on their side.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

REFERENCES*

• Koetse, Manya. 2021. “The Unforgotten Victory: Why ‘The Battle at Lake Changjin’ Is One of China’s Biggest Films Yet.” What’s on Weibo, November 4 https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-unforgotten-victory-why-the-battle-at-lake -changjin-is-one-of-chinas-biggest-films-yet/ [7.3.22].

• Liao Qin. 2022. “The Impact of the Russian-Ukrainian Conflict on World Patterns [俄乌冲突 对世界格局影响几何].” (In Chinese). Jiefang Daily, February 25: page 5.

• Mo Jingxi. 2022. “US adding fuel to Ukraine crisis ‘irresponsible.’” China Daily Hong Kong, February 24: page 1.

• Parsons, Paul and Xu Xiaoge. 2001. “New Framing of the Chinese Embassy Bombing by the People’s Daily and the New York Times.” Asian Journal of Communication 11 (1): 51- 67.

*All other sources are linked to within the text, both in Chinese and English language.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

You may like

China Media

China’s “AFP Filter” Meme: How Netizens Turned a Western Media Lens into Online Patriotism

Chinese netizens embraced a supposed “demonizing” Western gaze in AFP photos and made it their own.

Published

3 months agoon

September 10, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

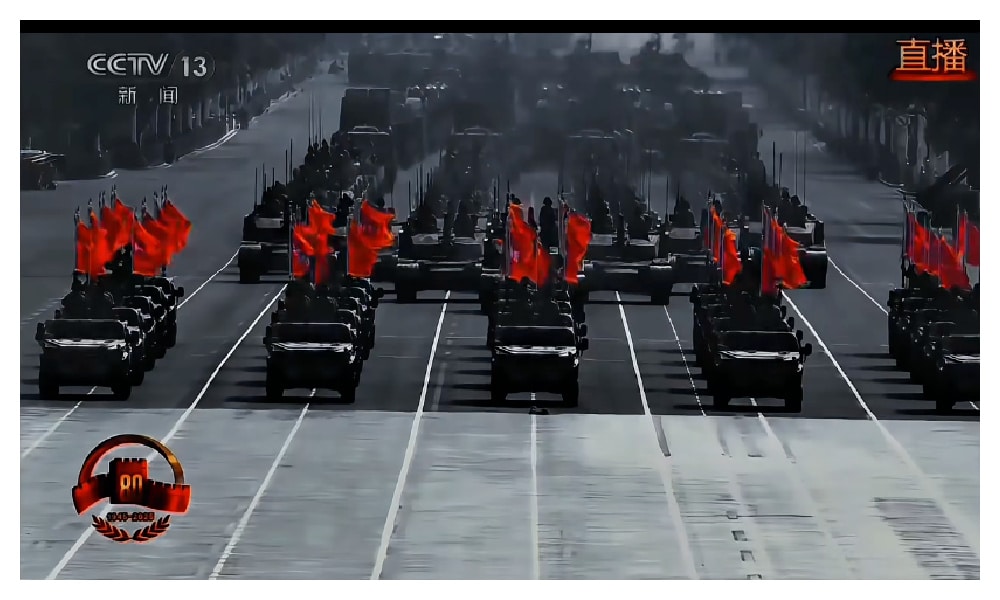

For a long time, Chinese netizens have criticized how photography of Chinese news events by Western outlets—from BBC and CNN to AFP—makes China look more gloomy or intimidating. During this year’s military parade, the so-called “AFP filter” once again became a hot topic—and perhaps not in the way you’d expect.

In the past week following the military parade, Chinese social media remained filled with discussions about the much-anticipated September 3 V-Day parade, a spectacle that had been hyped for weeks and watched by millions across the country.

That morning, Chinese leader Xi Jinping, accompanied by his wife Peng Liyuan, welcomed international guests on the red carpet. When Xi arrived at Tiananmen Square alongside Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, office phone calls across the country quieted, and school classes paused to tune in to one of China’s largest-ever military parades along Chang’an Avenue in Beijing, held to commemorate China’s victory over Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

As tanks rolled and jets thundered overhead, and state media outlets such as People’s Daily and Xinhua livestreamed the entire event, many different details—from what happened on Tiananmen Square to who attended, and what happened before and after, both online and offline—captured the attention of netizens.

Amid all the discussions online, one particularly hot conversation was about the visual coverage of the event, and focused on AFP (法新社), Agence France Press, the global news agency headquartered in Paris.

Typing “AFP” (法新社) into Weibo in the days after the parade pulled up a long list of hashtags:

- Has AFP released their shots yet?

- V-Day Parade through AFP’s lens

- AFP’s god-tier photo

- Did AFP show up for the parade?

The fixation may seem odd—why would Chinese netizens care so much about a French news agency?

Popular queries centered on AFP.

The story actually goes back to 2022.

In July of that year, on the anniversary of the Communist Party’s founding, one Weibo influencer (@Jokielicious) noted that while domestic photographers portrayed the celebrations as bright and triumphant, she personally preferred the darker, almost menacing image of Beijing captured by Western journalists. In her view, through their lens, China appeared more powerful—even a little terrifying.

The original post.

The post went viral. Soon, netizens began comparing more of China’s state media photos with those from Western outlets. One photo in particular stood out: Xinhua’s casual, cheerful shot of Chinese soldiers contrasted sharply with AFP’s cold, almost cinematic frame.

Same event, different vibe. Chinese social media users compared these photos of Xinhua (top) versus AFP (down). AFP photo shot by Fred Dufour.

Netizens joked that Xinhua had made the celebration look like the opening of a new hotel, while AFP had cast it as “the dawn of an empire.”

Gradually, what began as a dig at the bad aesthetics of state media turned into something else: a subtle shift in how Chinese netizens were rethinking their country’s international image.

Under the hashtag #ChinaThroughOthersLens (#老中他拍), netizens shared images of China as seen through the lenses of various Western media outlets.

This wasn’t the first time such talk had appeared. In the early days of the Chinese internet, people often spoke of the so-called “BBC filter.” The idea was that the BBC habitually put footage of China under a grayish filter, making its visuals give off a vibe of repression and doom, which many felt was at odds with the actual vibrancy on the ground. To them, it was proof that the West was bent on painting China as backward and gloomy.

These discussions have continued in recent years.

For example, on Weibo there were debates about a photo of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, shot by Peter Thomas for Reuters, and used in various Western media reports about Wuhan and Covid as early as 2021. The top image shows the photographer’s vantage point.

“Looks like a cockroach in the gutter,” one popular comment described it.

Top image by Chinese media, lower image by Peter Thomas/Reuters, and was used in various Western media reports about Wuhan and Covid since as early as 2021.

Another example is the alleged “smog filter” applied by Western media outlets to Beijing skies during the China visit of US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in 2024.

The alleged “smog filter” applied to Beijing skies during Blinken’s visit. Top image: Chinese media. Middle: BBC. Lower: Washington Post.

AFP, meanwhile, seemed to offer a different kind of ‘distortion.’

Netizens said AFP’s photos often had a low-saturation, high-contrast, solemn tone, with wide angles that made the scenes feel oppressive yet majestic. Over time, any photo with that look—whether taken by AFP or not—was dubbed the “AFP filter” (法新社滤镜).

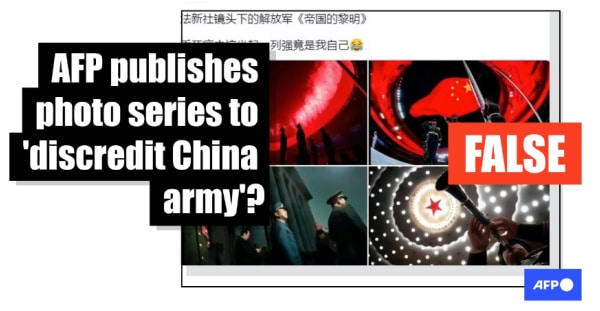

AFP has clarified multiple times that many of the viral examples weren’t even theirs—or that they were, but had been altered with an extra dark filter. They also refuted claims that AFP had published a photo series of Chinese soldiers titled “Dawn of Empire” to discredit China’s army.

AFP refuted claims that their photos discredited the Chinese army.

Nevertheless, the “AFP filter” label stuck. It became shorthand for a Western gaze that cast China not as impoverished or broken—as some claimed the “BBC filter” did—but as formidable, like a looming supervillain.

One running joke summed it up neatly: domestic shots are the festive version; Western shots are the red-tyrant version. And increasingly, netizens admitted they preferred the latter, commenting that while AFP shots often emphasize red to suggest authoritarianism, they actually like the red and what it stands for.

So, when this year’s V-Day came around, many were eager to see how AFP and other Western outlets would frame China as the dark, dangerous empire.

But when the photos dropped, the reaction was muted. They looked average. Some called them “disappointing.” “Where are the dark angles? Not doing it this time?” one blogger wondered. “Where’s the AFP hotline? I’d like to file a complaint!”

“Xinhua actually beat you this time,” some commented on AFP’s official Weibo account. Others agreed, putting the AFP photos and Xinhua photos side by side.

AFP photos on the left versus Xinhua photos on the right.

To make up for the letdown, people began editing the photos themselves—darkening the tones, adding dramatic shadows, and proudly labeling them with the tag “AFP filter” or calling it “The September 3rd Military Parade Through a AFP Lens” (法新社滤镜下的9.3阅兵). “Now that’s the right vibe,” they said: “I fixed it for you!”

Netizen @哔哔机 “AFP-fied” photos of the military parade by AFP.

Official media quickly picked up on the trend. Xinhua rolled out its own hashtags—#XinhuaAlwaysDeliversEpicShots (#新华社必出神图的决心#) and #XinhuaWins (#新华社秒了#)—and positioned itself as the true master of a new aesthetic narrative.

The message was clear: China no longer needs the Western gaze to frame itself as powerful or intimidating; it can do that on its own.

The “AFP v Xinhua” contest, the online movement to “AFP-ify” visuals, and the Chinese fandom around AFP’s moodier shots may have been wrapped in jokes and memes, but they also pointed to something deeper: the once “demonized” image of China that Western media pushed as threatening is now not only accepted by Chinese netizens, it’s embraced. Many have made it part of a confident, playful form of online patriotism, applauding the idea of being seen by the West as fearsome, even villainous, believing it amplifies China’s global authority.

As one netizen wrote: “I like it when we look like we crawl straight into their nightmares.”

Chinese journalist Kai Lei (@凯雷) suggested that these kinds of trends showed how the Chinese public plays an increasingly proactive role in shaping China’s global image.

By now, the AFP meme has become so strong that it doesn’t even require AFP anymore. Ultra-dramatic shots are simply called “AFP-level photos” (法新社级别).

For now, as many are enjoying the “afterglow” of the military parade, their appreciation for the AFP-style only seems to grow. As one Weibo user summed it up: “AFP tried to create a sense of oppression with dark, low-angle shots, but instead only strengthened the Chinese military’s aura of majesty.”

– By Ruixin Zhang and Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

From China’s first soap opera Yearnings to the rise of AI-fueled nostalgia.

Published

5 months agoon

July 2, 2025

The year is 1990, and the streets of Beijing’s Fangshan District are eerily quiet. You can almost hear a pin drop in the petrochemical town, as tens of thousands of workers and their families huddle around their televisions, all tuned to the same channel for something groundbreaking: China’s very first soap opera, Yearnings (渴望 Kěwàng).

Yearnings tells the story of Liu Huifang (刘慧芳), a female factory worker from a traditional working-class family in Beijing, and her unlikely marriage to university graduate Wang Husheng (王沪生), who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Liu finds an abandoned baby girl, she adopts her and raises her as her own, against her husband’s wishes.

The couple is unaware that the foundling is actually the illegitimate child of Wang’s snobbish sister, Yaru. After Liu and Wang have a biological son, the marriage comes under further pressure, eventually leading to divorce. Liu is left as a single mother, raising two children on her own.

Still from Yearnings, via OurChinaStory.

Drawing inspiration from foreign dubbed television shows, Yearnings was produced as China’s first truly domestic, long-form indoor television drama. Spanning 50 episodes, the series traces a timeline from the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s through to the late 1980s—one of the most turbulent periods in modern Chinese history.

Before the series aired nationally on CCTV and achieved record viewership, the first station to air Yearnings in the Beijing region was the Yanshan Petrochemical TV Station (燕山石化电视台), China’s first major factory TV station (厂办电视台) located in Fangshan District.

Here, in this town of over 100,000, Yearnings garnered an astonishing and unprecedented 98% audience share. The series was truly groundbreaking and became a national sensation—not just because it was China’s first long-form television drama, or because it was a locally produced drama that challenged the long-standing monopoly of state broadcaster CCTV, but because Yearnings marked a major shift in television storytelling.

Until then, Chinese TV stories had always revolved around communist propaganda, or featured great heroes of the revolution. Yearnings, on the other hand, was devoid of political content and focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary people and their everyday struggles—love, desire, marital tension, single motherhood—topics that had never before been so openly portrayed on Chinese television.

The show’s creators had perfectly tapped into what was changing: the Communist Party was slowly withdrawing from private life, and people were beginning to see themselves less defined by their work unit and more by their home life—as consumers, as partners and parents, as citizens of a new China filled with aspirations for the future. Yearnings’ storyline was a reflection of that.

Chinese-Style “Nostalgia Core”

Yearnings marked a cultural turning point, coinciding with the rapid spread of TV sets in Chinese households. In 1992, economic reforms triggered a new era in which Chinese media became increasingly commercialized and thriving, before the arrival of the internet, social media, and AI tools once again changed everything.

Today, Yearnings still is a topic that often comes up in Chinese online media. On apps like Douyin, old scenes from Yearnings are reposted and receive thousands of shares.

📌 It’s emblematic of a broader trend in which more netizens are turning to “nostalgia-core.” In Chinese, this trend is known as “中式梦核” (Zhōngshì Mènghé), which literally means “Chinese-style dreamcore.”

Dreamcore is an internet aesthetic and visual style—popular in online communities like Tumblr and Reddit—that blends elements of nostalgia, surrealism, and subconscious imagery. Mixing retro images with fantasy, it evokes a sense of familiarity, yet often feels unsettling and deserted.

The Chinese-style dreamcore (中式梦核), which has become increasingly popular on platforms like Bilibili since 2023-2024, is different from its Western counterpart in how it incorporates distinctly Chinese elements and specifically evokes the childhood experiences of the millennial generation. Content tagged as “Chinese-style dreamcore” on Chinese social media is often also labeled with terms like “nostalgia” (怀旧), “childhood memories” (童年回忆), “when we were little” (小时候), and “Millennial Dream” (千禧梦).

According to the blogging account Yatong Local Life Observer (娅桐本地生活观察), the focus on the millennial childhood can be explained because the formative years of this generation coincided with a decade of rapid social change in China —leaving little in today’s modern cities that still evokes that era.

🌀 Of course, millennials in the West also frequently look back at their childhood and teenage years, particularly the 1980s and 1990s—a trend also embraced by Gen Z, who romanticize these years through media and fashion. In China, however, Gen Z is at the forefront of the “nostalgia-core” trend, reflecting on the 1990s and early 2000s as a distant, almost dreamlike past. This sense of distance is heightened by China’s staggering pace of transformation, modernization, and digitalization over the past decades, which has made even the recent past feel remote and irretrievable.

🌀 Another factor contributing to the trend is that China’s younger generations are caught in a rat race of academic and professional competition, often feeling overwhelmed by the fast pace of life and the weight of societal expectations. In this high-pressure environment—captured by the concept of “involution” (内卷)—young people develop various coping mechanisms, and digital escapism, including nostalgia-core, is one of them. It’s like a cyber-utopia (赛博乌托邦).

🌀 Due to the rise of AI tools available to the general public, Chinese-style nostalgia core has hit the mainstream because it’s now possible for all social media users to create their own nostalgic videos and images—bringing back the 1990s and early 2000s through AI-generated tools, either by making real videos appear more nostalgic or by creating entirely fictional videos or images that recreate scenes from those days.

So what are we seeing? There are images and videos of stickers kids used to love, visuals showing old classrooms, furniture, and children playing outside, accompanied by captions such as “we’re already so far apart from our childhood years” (example).

Images displayed in Chinese Dreamcore.

And notably, there are videos and images showing family and friends gathering around those old big TVs as a cultural, ritualized activity (see some examples here).

Stills from ‘nostalgia core’ videos.

These kinds of AI-generated videos depict a pre-mobile-era family life, where families and communities would gather around the TV—both inside and outside—from classrooms to family homes. The wind blows through the windows, neighbors crack sunflower seeds, and children play on the ground. Ironically, it’s AI that is bringing back the memories of a society that was not yet digitalized.

Nowadays, with dozens of short video apps, streaming platforms, and livestream culture fully mainstream in China—and AI algorithms personalizing feeds to the extreme—it sometimes feels like everyone’s on a different channel, quite literally.

In times like these, people long for an era when life seemed less complicated—when, instead of everyone staring at their own screens, families and neighbors gathered around one screen together.

There’s not just irony in the fact that it took AI for netizens to visualize their longing for a bygone era; there’s also a deeper irony in how Yearnings once represented a time when people were looking forward to the future—only to find that the future is now looking back, yearning for the days of Yearnings.

It seems we’re always looking back, reminiscing about the years behind us with a touch of nostalgia. We’re more digitalized than ever, yet somehow less connected. We yearn for a time when everyone was watching the same screen, at the same time, together, just like in 1990. Perhaps it’s time for another Yearnings.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Sources (other sources included in hyperlinks)

Koetse, Manya. 2016. “From Woman Warrior to Good Wife – Confucian Influences on the Portrayal of Women in China’s Television Drama.” In Stefania Travagnin (ed), Religion and Media in China. New York: Routledge.

Rofel, Lisa B. 1994. Yearnings: Televisual Love and Melodramatic Politics in Contemporary China. American Ethnologist 21(4):700-722.

Wang, Dan (汪丹). 2018. “《渴望》的艺术价值” [The Artistic Value of Yearnings].” Originally published in Beijing Daily (北京日报), October 12, 2018. Reprinted in Digest News (文摘报), October 20, 06 edition. Also see Sohu: 当年红遍大江南北的《渴望》.

Wang Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, a Chinese television soap opera with a message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Zhuge Kanwu. 2021. “重温1990《渴望》:苦得“刘慧芳”希望被导演写“死” [Revisiting 1990’s Yearnings: The Suffering Liu Huifang Hoped to Be Written Off by the Director]. Zhuge Dushu Wu (诸葛读书屋), January 22. https://wapbaike.baidu.com/tashuo/browse/content?id=b699ee532cf79f862bfa14ad.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral5 months ago

China Memes & Viral5 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital11 months ago

China Digital11 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained