Newsletter

Weibo Watch: A New Chapter

About balloons, drone dragons, changes coming to What’s on Weibo, and much more.

Published

11 months agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #42

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – A New Chapter

◼︎ 2. What’s New – A closer look at featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Noteworthy – A strange record

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Jackson Yee’s stellar performance

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Looking back at the 10 most-read stories of 2024

Dear Reader,

From Hangzhou to Wuhan, the New Year in China was celebrated with the release of thousands of balloons at midnight in cities across the country. In Hangzhou alone, approximately 70,000 people attended the New Year countdown celebrations, with some bloggers estimating that street vendors sold at least 20,000 balloons in one night. In Nanchang, the capital of Jiangxi province, thousands of people also released balloons in the city center, resulting in stunning crowd videos (see here).

While a sky filled with balloons makes for some spectacular images and footage, adding to the festive sphere, there are also worries about this contemporary ‘tradition.’

The Nanchang balloon moment at midnight.

The sight of tens of thousands of people gathering in city centers, such as in Nanchang, has triggered discussions about the dangers of unexpected incidents leading to panic, potentially causing stampedes like the tragic event in Shanghai a decade ago.

Beyond crowd safety, the release of thousands of balloons introduces another serious risk. Hydrogen-filled balloons (hydrogen is often illegally used in balloons because it’s cheaper than helium) are highly flammable, and contact with high-voltage lines or open flames can lead to explosions and hazardous situations. One such incident occurred in Xinyang on New Year’s Eve, when balloons exploded at the crowded entrance of a shopping mall (video). In Hangzhou, a 22-year-man was arrested at the scene for setting off fireworks in Hangzhou during the balloon release festivities, also causing local explosions.

And then, there are concerns about the environmental impact. The balloon release festivities in Hangzhou alone resulted in an estimated six tons of garbage being left behind, making the cleanup a massive and costly undertaking. While sanitation workers are mobilized to tackle the mess, many balloons end up caught in trees, tangled in bushes, or drifting so far that they’re beyond the reach of cleanup crews. The sheer amount of plastic waste left behind has sparked online discussions, with many questioning the environmental consequences of these celebrations.

So what’s the alternative?

This year, you might have seen a viral video of an impressive drone show supposedly held on the Bund in Shanghai, featuring a dragon formed by dozens of drones dancing in the night sky, crowned by a circle of fireworks. The video went viral across Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and X. Even Elon Musk liked the video, tweeting his “wow” comment: look how China celebrates the New Year!

The video, however, turned out to be fake. In fact, there was no show for New Year’s at the Bund at all.

The video creator combined elements from various other videos, including a drone light show featuring a majestic dragon that took place in Shenzhen on October 1st, marking the 75th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China (video).

The glowing circle in the sky was from a firework and AI show held in Liuyang, Hunan, on December 7, titled “Tears of the Gate of Heaven” (天空之门的眼泪). The falling lights symbolized tears from heaven and were designed by a local firework company boss to commemorate his late mother (video).

Upon further research, I found that the Liuyang show had inspired a series of edited videos, placing the Liuyang show highlight in different locations, with each version more spectacular than the last (see examples). As reported by Annielab, there are even online tutorials teaching netizens how to digitally insert the Liuyang ‘gate’ into different backgrounds with the Jianying (剪映, aka Capcut) editing app.

What began as an online meme (“I haven’t been to the Liuyang show, but I can bring it to my town”) eventually resulted in the viral video combining the Shenzhen and Liuyang shows against the backdrop of the Bund. For the quick scrollers, it apparently was so realistic that even Elon Musk thought it was genuine.

Stills from the fake drone dragon video.

The fake drone dragon New Year video is interesting for several reasons. It highlights how quickly fake news about China spreads across social media, with few questioning the authenticity of viral posts—even when they’re shared with millions of followers. We’ve seen this pattern before, with stories about the social credit system, a supposed Xi Jinping chatbot, and heavily edited cyberpunk-style Chongqing scenes.

These trends often repeat themselves, portraying China in extremes: either as a futuristic utopia or a dystopian threat. They go viral because they serve as clickbait, used by both hostile “anti-China” accounts and propaganda-heavy “pro-China” accounts to push their narratives—look how great China is or look how scary China is.

The dragon video, though fake, also underscores China’s role as a global tech power. Its components—real drone and AI shows in Liuyang, Shenzhen, and other cities—demonstrate just how advanced the technology has become, to the point where reality and fabrication are increasingly difficult to distinguish.

It’s just a video, but it points to something bigger: the lack of understanding about what is actually happening in China. Whether it’s about China’s digital space or society at large, most people don’t take the time—or simply don’t have the time—to look beyond the surface of fast-moving stories. This tendency risks amplifying misconceptions. Before you know it, you might retweet a fake dragon video, interpreting it as evidence of a powerful or intimidating China, without realizing it’s part of a broader grassroots trend that’s misunderstood—or missing the fact that, for now, far more balloons than drones still rise into the skies during New Year’s celebrations.

Before I wander off with the balloons, what’s the takeaway? As we step into 2025, with AI playing an ever-growing role on social media and global influencers shaping the news we consume—often with their own agendas—it’s more important than ever to examine the stories we amplify critically. Only by paying attention to the details can we truly understand the bigger picture.

Announcing some changes to What’s on Weibo

This brings me to an exciting new chapter for What’s on Weibo and how I see the future of the site. The China-focused global news environment has evolved significantly since I first started this platform. There’s now an increased focus in mainstream media on China’s social media trends, and niche China-related news has become accessible to many thanks to innovative tools at our fingertips. While there’s more information than ever, it’s also becoming increasingly chaotic and fleeting.

As a smaller, independent voice in this fast-paced and crowded media arena, I’m committed to offering you unique and meaningful insights into Chinese society and digital culture that you won’t find anywhere else. In this video, I’ll explain the changes coming to the site, introducing What’s on Weibo Chapters. In these turbulent, dragon-drone times, I hope you’ll appreciate this new chapter for What’s on Weibo.

Our first Chapter, of course, is “15 Years of Weibo,” reflecting on the platform’s evolution since its launch in 2009 and its role in China’s competitive social media ecosystem today. We’ll explore the most popular influencers on Weibo, go deeper into Weibo diplomacy aka ‘Weiplomacy’, and will feature a special contribution by an expert guest writer. More on that coming soon!

A shout-out to Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang for helping select some of the topics for this newsletter, and a very special thanks to Wytse Koetse for filming and editing the What’s on Weibo Chapters video.

Stay tuned!

Warm greetings,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

What’s New

Our picks | From ‘Chillax’ to ‘Digital Ibuprofen,’ this compilation of ten Chinese buzzwords and catchphrases by What’s on Weibo reflects social trends and the changing times in China in 2024.

What’s Trending

🏚️ Earthquake in Tibet

The devastating 7.1 magnitude earthquake that struck Shigatse’s Tingri County high on the Tibetan plateau on the morning of January 7th has already claimed the lives of at least 95 people and left over 130 injured. Approximately 6,900 people reside in the villages surrounding the earthquake’s epicenter. On Weibo, videos reveal the catastrophic impact of the earthquake, with entire neighborhoods reduced to rubble.

Shigatse City’s Deputy Mayor Liu Huazhong (刘华忠) appeared visibly emotional as he announced the latest death toll and shared that 14 townships have been severely affected by the disaster. At the time of writing, the government has activated the highest-level emergency response for disaster relief, with hundreds of rescue workers deployed to the affected areas to provide medical assistance, conduct search and rescue operations, and distribute emergency supplies.

🤒 Peak Flu Season

It’s peak flu season, and it’s evident in the various trending topics circulating on Chinese social media. As discussions grow about crowded hospitals, face masks, and flu medication, concerns about the rapidly rising rates of influenza viruses have also emerged. Currently, according to monitoring data from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, over 99% of flu cases in China are identified as the Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 (“甲流”).

There have also been reports of an increase in flu-like human metapneumovirus (HMPV, 人偏肺病毒) infections in northern China, particularly among children under the age of 14. On social media, Chinese experts are largely addressing these concerns by emphasizing that HMPV is not the same as Covid-19, is less common compared to influenza and mycoplasma infections, and that the recent rise in HMPV cases is not unusual but rather reflects the typical higher prevalence of respiratory viruses during winter.

🏓 Chinese Table Tennis Superstars Withdraw from World Rankings

There has been a lot of buzz about the world of table tennis recently. After a tumultuous 2024 in which Chinese table tennis players shone at the Paris Olympics, super popular table tennis stars Fan Zhendong (樊振东) and Chen Meng (陈梦) announced on Weibo (post 1, post 2) their withdrawal from the World Rankings (WR) due to new fines imposed by the International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF) for players not participating in tournaments.

Fan wrote that the Paris Olympics had left him “mentally exhausted” and that the new rules imposing fines for not participating in tournaments left him no other choice but to withdraw entirely. He also said he would not retire yet and quoted the Wicked line, “It’s time to try defying gravity 💚.” That post received more than 2.8 million (!) likes. Likewise, Chen also wrote about the impact of Olympic stress and that she still needs time to recover.

The withdrawal of these major table tennis icons—veteran athlete Ma Long (马龙) later also announced his withdrawal—has ignited discussions and criticism over WTT’s mandatory participation rule and whether it merely serves commercial interests instead of protecting athletes. Liu Guoliang (刘国梁), president of the Chinese Table Tennis Association (CTTA), said he would press World Table Tennis to revise its rules.

🏛️ Verdict in Handan Schoolboy Murder Case

A case in which a young boy from Feixiang County in Handan, Hebei, was murdered by three classmates shocked the nation in March 2024. The young boy, Wang Ziyao (王子耀), had suffered years of bullying before his three classmates, all 13 years old, killed and buried him. Wang had been missing for one day before his body was discovered buried in a greenhouse in a field near the home of one of the suspects. The case attracted major attention at the time, not just because of the cruel crime, but also due to its legal implications. Since an amendment to China’s Criminal Law in 2021, children between the ages of 12 and 14 can be held criminally responsible for extreme and cruel cases resulting in death or severe disability, if approved for prosecution by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP).

Now, the court verdict has been reported by Chinese media. Two of the male defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment, while the third defendant was not legally punished due to his minor role in the crime but was still placed under “special correctional education.” The verdict has triggered discussions on its implications and how it should now be clear to minors aged 12 and above, and their parents, that they cannot escape severe punishment for extreme crimes.

🎬 Li Mingde’s Livestream Permanently Banned

The young Chinese actor Li Mingde (李明德), also known as Marcus Li, has been the center of attention on Chinese social media recently due to the drama surrounding the production of the Chinese TV series The Triple Echo of Time (三人行). In a Weibo post published on the night of January 4, Li, a supporting actor in the series, accused co-star Ma Tianyu (马天宇), the male lead, of displaying diva behavior on set. He also complained about the harsh filming conditions, alleging that he was made to wait in freezing temperatures wearing nothing but a t-shirt.

The production team has since issued a statement denying Li’s claims and turned the tables, accusing Li of being unreasonable, negative, and frequently late or leaving early during filming. They also confirmed that they had officially terminated their collaboration with him.

Adding to the controversy, Li Mingde’s livestream channel was suddenly shut down on January 7, with Douyin permanently banning his account. The platform cited “deliberately stirring controversy to attract attention” as the reason for the ban, sparking widespread discussion online. Li, who has over 7.6 million followers on Weibo, continues to post updates at the time of writing. After Ma Tianyu suggested in a now-deleted post that Li might be suffering from a mental illness, Li refuted the claim and stated he plans to take legal action. It seems this drama is far from over.

What’s Noteworthy

Did you know that the final Guinness World Record of 2024 was set by Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com? Honestly, the record is so unusual that I initially struggled to understand what the achievement was: JD.com now holds the Guinness World Record for the world’s “largest object unveiled” in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan, on December 29, 2024—a staggering 400.66 meters long.

Is it a rocket? A train? A cruise ship?

No, it’s actually a list of 173,583 authentic user comments—a 400-meter-long comment section reviewing the platform’s major home appliance products. JD.com, one of the leading players in China’s home goods and household appliances market, seems to have orchestrated this extravagant marketing stunt to emphasize its position as a trustworthy market leader with an alleged 98% satisfaction rate.

The 400+ meter list, via Digitaling.

As an online retailer, printing reviews and displaying them in an offline setting where virtually no one but Guinness World Records takes notice does seem wasteful. But here we are, talking about it—along with a trending hashtag (#24年最后一个吉尼斯纪录是京东的#), so I suppose the PR effort paid off.

What’s Popular

After the 2024 success of Her Story(好东西) directed by Shao Yihui (邵艺辉) YOLO (麻辣滚烫) by Jia Ling (贾玲), Like A Rolling Stone (出走的决心) by Yin Lichuan (尹丽川), we are now seeing another hit film by a female director, highlighting the growing prominence of female directors in Chinese cinema.

The hashtag for the new movie Little Me (小小的我) has received over a billion views on Weibo this week (#电影小小的我#), noting its popularity. The movie was directed by Yang Lina (杨荔钠), the female director also known for her film Song of Spring (妈妈), which tells the moving story of an 85-year-old mother caring for her 65-year-old daughter with Alzheimer’s disease.

Little Me again touches on profound themes as it tells the story of a young man suffering from cerebral palsy who nevertheless tries to find his own direction in life. The role is played by Jackson Yee (易烊千玺), the superstar with an enormous fanbase on social media. Although he is still known as the youngest member of the boyband TFboys, Yee has gone far beyond that and shows his talent and dedication as an actor in this film with a credible performance.

Although Jackson Yee’s standout performance in Little Me is praised across social media, some have also commented that the actor might be too good for the film. Qilu Evening News published a sharp movie review, noting that Yee’s performance creates a stark divide between his brilliance and the film’s otherwise mediocre quality. This disparity has led some viewers to comment that Little Me is “a dumpling made just for the vinegar” (“为了一碟醋包了一顿饺子”). Despite this criticism, the film is still scoring a 7.2 on the Douban platform, where it has been rated by over 164,000 people.

What’s Memorable

As we’re entering the second week of 2025, I’d still like to take this time to look back look back at 10 of the most popular stories on

What’s On Weibo of 2024 for this week’s archive lookback. From viral trends to shocking incidents, it was a tumultuous year with some moments that’ll be ingrained in China’s collective digital memory. 🧵👇

1️⃣🐱 When ‘Fat Cat’ Jumped into the Yangtze River | He invested all he had for a girl he’d met online. Then she broke up with him. The tragic story behind the suicide of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ (胖猫) became a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media in May of 2024, touching upon broader societal issues from unfair gender dynamics to businesses taking advantage of grieving internet users.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-tragic-story-of-fat-cat-how-a-chinese-gamers-suicide-went-viral/

2️⃣✨ Chengdu Disney | How did a common park in Chengdu turn into a hotspot that got everyone talking? By mixing online trends with real-life fun, blending foreign styles with local charm, and adding humor and absurdity, Chengdu had the recipe for its very own ‘Chengdu Disney’ in 2024. Undeniably, the quirkiest trend of the year.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chengdu-disney-the-quirkiest-hotspot-in-china/

3️⃣💧 Nongfu and Nationalists | One of the most noteworthy online phenomena in China during 2024 was the big battle over bottled water after the death of Zong Qinghou (宗庆后), the founder and chairman of Wahaha Group (娃哈哈集团), the country’s largest beverage produce. What started as a support campaign for Wahaha morphed into a crusade against another major water brand, Nongfu Spring, led by online nationalists.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/in-hot-water-the-nongfu-spring-controversy-explained/

4️⃣🔪 Beishan Park Stabbings | 2024 was, unfortunately, a year of many deadly mass attacks by individuals ‘taking revenge on society,’ from Zhuhai to Changde. One such incident that made headlines around the world was the June 10 stabbing at Beishan Park in Jilin, which left four American teachers injured, among others. While the story spread widely on X, it was initially kept under wraps on the Chinese internet. This article analyzes how the incident was reported, censored, and discussed on Weibo.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-beishan-park-stabbings-how-the-story-unfolded-and-was-censored-on-weibo/

5️⃣🥇 Golden Olympics | The 2024 Paris Olympics were the talk of Chinese social media. Beyond the gold medal moments, there were plenty of happenings on the sidelines, at the venues, and on the award stage that went viral, sparking countless memes. From China’s cutest weightlifter to viral sensation Quan Hongchan, this top 10 list of meme-worthy moments was a favorite among readers.

🔗

Team China’s 10 Most Meme-Worthy Moments at the 2024 Paris Olympics

6️⃣🚗 Land Rover Woman | In 2024, ‘Land Rover Woman’ (路虎女) became the latest addition to the Chinese Lexicon of Viral Incidents. A female Land Rover driver sparked outrage among Chinese netizens with her entitled behavior, driving against traffic and reacting aggressively when confronted—even striking a Chinese veteran in the face. The incident highlighted widespread frustration with social class injustice, as many viewed it as reflecting existing power imbalances between the wealthy and the working-class.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/weibo-watch-the-land-rover-woman-controversy-explained/

7️⃣🧮 Controversial Math Genius Jiang Ping | It’s rare for a math competition to become the focus of nationwide attention in China. But when 17-year-old vocational school student Jiang Ping made it to the top 12 of Alibaba’s Global Math Competition, competing against contestants from prestigious universities worldwide, her humble background and outstanding achievement sparked debates and triggered rumors. She was called China’s version of Good Will Hunting, but her math story had a disappointing ending.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chinas-controversial-math-genius-jiang-ping/

8️⃣🇺🇸 Trump’s Triumph |The assassination attempt on former US President (now President-elect) Trump at a Pennsylvania campaign event in July 2024 became a major topic on Chinese social media. Trump’s swift reaction and defiant gesture after the shooting not only sparked widespread discussions but also fueled the “Comrade Trump” meme machine.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/a-triumph-for-comrade-trump-chinese-social-media-reactions-to-trump-rally-shooting/

9️⃣📚 Crusade against Smut | A recent crackdown on Chinese authors writing erotic web novels sparked increased online discussions about the Haitang Literature ‘Flower Market’ subculture, the challenges faced by prominent online smut writers, and the evolving regulations surrounding digital erotica in China. But how serious is the “crime” of writing explicit fiction in China today? Ruixin Zhang explored this topic in an insightful and widely-read article, with a sad update.

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-price-of-writing-smut-inside-chinas-crackdown-on-erotic-fiction/

🔟🚴♂️ Cycling to Kaifeng | The term ‘yè qí‘ (夜骑), meaning “night ride,” suddenly became a buzzword on Chinese social media in late fall of 2024, as large groups of students from various schools and universities in Zhengzhou started cycling en masse to the neighboring city of Kaifeng on shared bicycles in the middle of the night. From city marketing to the spirit of China’s new generation, there are many themes behind their nightly cycling caravan, explained in this article, which also became one of the best-read pieces on What’s on Weibo this year:

🔗

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-cycling-to-kaifeng-trend-how-it-started-how-its-going/

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

Dear Reader

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

A look back at the three major phases of China’s social media — and why What’s on Weibo is evolving into Eye on Digital China.

Published

2 weeks agoon

November 12, 2025

This edition of the Eye on Digital China newsletter by Manya Koetse was sent to premium subscribers. Subscribe now to receive future issues in your inbox.

“Do you still remember going to the internet cafe, paying 2 yuan ($0.30) per hour during the day or 7 yuan ($1) for an all-nighter? Staying up playing games and surfing around?”

It’s the kind of content you’ll often see today on platforms like Douyin or Bilibili — nostalgic videos showing smoky internet cafes (wangba 网吧) from the early 2000s, where people chatted on QQ or played World of Warcraft on old Windows PCs while eating instant noodles. These clips trigger waves of nostalgia, even among internet users too young to remember that era themselves.

Internetcafe in 2005, image via 021zhaopin.com

The current nostalgia wave you see on Chinese social media is indicative of how China’s digital world has evolved over the past 25 years, shifting from one era to the next.

As I welcome a new name for this newsletter and say goodbye to ‘Weibo Watch’— and, in the longer run, to the ‘What’s on Weibo’ title, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic myself. It seems like a good moment to look back at the three major stages of Chinese social media, and at the reason I started What’s on Weibo in the first place.

1. The Blogging Boom (2002–2009): The Early Rise of Chinese Social Media

When I first came to China and became particularly interested in its online environment, it was the final phase of the early era of Chinese social media — a period that followed soon after the country had laid the foundations for its internet revolution. By 1999, the first generation of Chinese internet giants — Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Sina — had already been founded.

China’s blogging era began with the 2002 launch of the platform BlogChina.com (博客中国), followed by a wave of new platforms and online communities, among them Baidu Tieba and Renren. By around 2005, there were roughly 111 million internet users and 16 million bloggers, and the social impact was undeniable. 2005 was even dubbed China’s “year of blogging.” 1

Chinese writer Han Han (韩寒, born 1982), a high-school-dropout-turned–rally car racer, became one of the most-read figures on the Chinese internet with his sharp and witty blogs. He was just one among many who rose to fame during the blog era, becoming the voice of China’s post-1980s youth.

The rebel of China’s blog era, Han Han, became of voice of his generation.

When I moved to Beijing in 2008, I had a friend who was always out of money and practically lived in an internet cafe in the city’s Wudaokou district, not far from where I studied. We would visit him there as if it were his living room — the wangba was a local hangout for many of us.

Not only online forums and blogging sites were flourishing at the time, but there was also instant messaging through QQ (腾讯QQ), online news reading, and gaming. Platforms like the YouTube equivalents Tudou (土豆) and Youku (优酷) were launched, and soon Chinese companies began developing more successful products inspired by American digital platforms, such as Fanfou (饭否), Zuosa (做啥), Jiwai (叽歪), and Taotao (滔滔), creating an online space that was increasingly, and uniquely, Chinese.

That trajectory only accelerated after 2009, when popular Western internet services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, became inaccessible from within mainland China.

⚡ The launch of Sina Weibo in 2009 came at a crossroads for China’s social media landscape: it was not only a time when many foreign platforms exited China, but also when internet cafes faced major crackdowns.

As a foreigner, I don’t think I ever visited internet bars in Beijing anymore by that point — internet use had largely shifted to home connections. Laptop ownership was rising, and we all had (pre-smartphone) mobile phones, which we used to text each other constantly, since texting was cheaper than calling.

Some of the mobile phones in China’s 2009 top 10 lists.

Weibo came at just the right time. It filled the vacuum left by the online crackdowns across China’s internet while still benefiting from the popularity of blogging. Weibo (微博), after all, literally means “micro-blog” — micro because the number of characters was limited, just like Twitter, making short-form posts the main way of communication.

Weibo quickly became hugely successful, for many more reasons than just timing. Its impact on society was so palpable that its trending discussions often seeped into everyday conversations I had with friends in China.

In English-language media, I kept reading about what was being censored on the Chinese internet, but that wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to know — I also wanted to know what was on Weibo, so I could keep up with my social circles.

That question planted the seed for What’s on Weibo: the simple curiosity of “What are people talking about?” What TV series are popular? What jokes and controversies are everyone discussing (but that I never fully grasped)? I wanted to get a sense of an online world that was, in many ways, intangible to outsiders — including myself. As I had moved back to Europe by then, it was also a way for me to stay connected to those everyday conversations unfolding online in China.

With scissors, glue, and some paper, I started sketching out what a future website might look like.

Papercrafting the idea for a website named ‘What’s on Weibo’ in 2012.

And in March 2013, after doing my best to piece it together, I launched What’s on Weibo and began writing — about all kinds of trends, like the milk powder crisis, about China’s many unmarried “leftover men” (shengnan 剩男), and about the word of the moment, “Green Tea Bitch” (lǜchá biǎo 绿茶婊) — a term used to stereotype ambitious women who act sweet and innocent while being seen as calculating or cunning.

2. From Weibo to the Taobao Moment: China’s Mobile Social Era: (2010–2019)

Around 2014–2015, people started saying Weibo was dead. In fact, it hadn’t died at all — some of its most vibrant years were still ahead. It had simply stumbled into the mobile era, along with China’s entire social media landscape.

As mobile internet became more widespread and everyone started using WeChat (launched in 2011), new mobile-first platforms began to emerge.2 In 2012–2013, for example, apps like Toutiao and Xiaohongshu (小红书, RED) were launched as mobile community platforms. With the rapid rise of China’s new tech giants — Bytedance, Meituan, and Didi — a new mobile era was blossoming, leaving the PC-based social media world far behind.

Spending another summer in Beijing in 2014, I called it the “Taobao Moment” — Taobao being China’s most successful online marketplace, a platform for buying and selling practically everything from clothes and furniture to insurance and even Bitcoins. At the time, I thought Taobao captured everything Beijing was at that moment: a world of opportunities, quick decisions, and endless ways to earn and spend money.

On weekends, some of my friends would head to the markets near the Beijing Zoo to buy the latest dresses, purses, jeans, or shoes. They’d buy stock on Saturday, do a photo shoot on Sunday, and sell the goods online by Monday. You could often spot young people on the streets of Beijing staging their own fashion shoots for Taobao — friends posing as models, Canon cameras in hand.

During that period, What’s on Weibo gradually found its audience, as more people became curious about what was happening on Chinese social media.

Around 2016, Weibo entered another prime era as the “celebrity economy” took off and a wave of “super influencers” (超级红人) emerged on the platform. Papi Jiang stood out among them — her humorous videos on everyday social issues made her one of China’s most recognizable online personalities, helping to drive Weibo’s renewed popularity.

Witty Papi Jiang was a breath of fresh air on Weibo in 2016.

People were hooked on social media. Between 2015 and 2018, China entered the age of algorithm- & interest-driven multimedia platforms. The popularity of Kuaishou’s livestreaming and Bytedance’s Douyin signaled the start of an entirely new era.

3. The New Social Era of AI-fication and Diversification (2020–Current)

China’s social media shifts over the past 25 years go hand in hand with broader technological, social, and geopolitical changes. Although this holds true elsewhere too, it’s especially the case in China, where central leadership is deeply involved in how social media should be managed and which direction the country’s digital development should take.

Since the late 2010s, China’s focus on AI has permeated every layer of society. AI-driven recommendation systems have fundamentally changed how Chinese users consume information. Far more than Weibo, platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu have become popular for using machine-learning algorithms to tailor feeds based on user behavior.

China’s social media boom has put pressure on traditional media outlets, which are now increasingly weaving themselves into social media infrastructure to broaden their impact. This has blurred the line between social media and state media, creating a complex online media ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s not just AI and media convergence that are reshaping China’s online landscape — social relationships now dominate both information flows and influence flows. 3 Not everyone is reading the same headlines anymore; people spend more time within their own interest-based niches. It’s no longer about microblogging but about micro-communities.

China now has 1.12 billion internet users. Among new users, young people (aged 10–19) and the elderly (60+) account for 49% and nearly 21%, respectively. The country’s digital environment has never been more lively, and social media has never been more booming.

As a bit of a dinosaur in China’s social media world, Weibo still stands tall — and its trending topics still matter. But the community that was once at the heart of the Chinese internet has dispersed across other apps, where people now engage in more diverse ways than ever.

In China, I notice this shift: where I once saw the rise of Weibo, the Taobao boom, or the Douyin craze, I now see online and offline media increasingly converging. Social media shapes real-life experiences and vice versa, and AI has become integrated into nearly every part of the media ecosystem — changing how content is made, distributed, consumed, and controlled.

In this changing landscape, the mission of What’s on Weibo — to explain China’s digital culture, media, and social trends, and to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online spaces — has stayed the same. But the name no longer fits that mission.

Over the past few years, my work has naturally evolved from Weibo-focused coverage to exploring China’s digital culture through a broader lens. The analysis and trend updates will continue, but under a new name that better reflects a time when Weibo is no longer at the center of China’s social media world: Eye on Digital China.

For you as a subscriber (subscribe here), this means you can expect more newsletter-based coverage: shorter China Trend Watch editions to keep you up to date with the latest trends, along with other thematic features and ‘Chapter’ deep dives that explore the depth behind fleeting moments.

For now, the main website will remain What’s on Weibo, but it will gradually transition into Eye on Digital China. I’ll keep the full archive alive — more than twelve years of coverage that helps trace the digital patterns we’re still seeing today. After all, the story of China’s past online moments often tells us more about the future than the trends of the day.

Thank you for following along on this new journey.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 Liu, Fengshu. 2011. Urban Youth in China: Modernity, the Internet and the Self. New York: Routledge, 50.

2 Mao Lin (Michael). 2020. “中国互联网25年变迁:两次跃迁,四次浪潮,一次赌未来” [25 Years of China’s Internet: Two Leaps, Four Waves, and a Gamble on the Future]. 人人都是产品经理 (Everyone Is a Product Manager), January 3. https://www.woshipm.com/it/3282708.html.

3 Yang, Shaoli (杨绍丽). 2025. “研判2025!中国社交媒体行业发展历程、重点企业分析及未来前景展望:随着移动互联网兴起,社交媒体开始向移动端转移 [Outlook for 2025! The Development History, Key Enterprises, and Future Prospects of China’s Social Media Industry: With the Rise of Mobile Internet, Social Media Has Shifted to Mobile Platforms].” Zhiyan Consulting (智研咨询), February 7. https://www.chyxx.com/industry/1211618.html.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in the comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient — we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo.

Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. Both feature the same new content — so you can subscribe or read wherever you prefer. If you’re already subscribed on one platform and would like to move your subscription over, just let me know and I’ll help you get set up.

© 2025 Manya Koetse. All rights reserved.

China Media

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Published

8 months agoon

March 30, 2025

“This man is doing God’s work. In just six hours, he eliminated all Western media propaganda about China,” Chinese influencer Li Sanjin (李三金) said in one of his videos this week. The man he referred to, allegedly doing ‘God’s work,’ is the American YouTuber and online streamer Darren Watkins, better known as IShowSpeed or Speed, who visited China this week and livestreamed from various locations.

With 37 million followers on his YouTube account, Watkins’ visit hasn’t exactly flown under the radar. His streams from China have already accumulated over 17.5 million views on YouTube alone, and he also became the talk of the week on Chinese social media.

In China, the 20-year-old IShowSpeed is known as Jiǎkànggē (甲亢哥), or “Hyper Bro,” since the immensely popular YouTube star is known for being highly energetic.

Although IShowSpeed is originally known for soccer and gaming-related content, he’s been streaming live from various countries over the past year, from Ecuador to Bolivia, from Australia to Indonesia, from Romania to Japan, and also from the Netherlands, where a mob of fans harassed the YouTuber to such an extent that the influencer fled and panicked, until the police intervened and asked him to shut down the livestream for safety reasons — which he did not comply with.

It was not the only time IShowSpeed’s visit got chaotic. He also got into trouble during livestreams from other countries. While streaming from Norway, he injured his ankle and was swarmed by a crowd while trying to get out. In Greece and Indonesia, he had to ask for police support as well. In Thailand, he crashed a tuk-tuk into a temple wall.

In China, IShowSpeed’s livestreams went far more smoothly, and netizens, state media, and other official channels raved about his visit and its favorable portrayal of the country and its culture.

🔹 Symbol of Cultural Exchange & Positive Diplomacy

“Jiǎkànggē” became one of the viral terms of the week, on Weibo, Kuaishou, Douyin, and Toutiao. During his China trip, the livestreamer hit several YouTube milestones — not only breaking the 37 million subscriber mark while on stream, but also surpassing the magic number of 10 million views in total.

Watkins, also known for being (sometimes aggressively) loud and chaotic, suddenly emerged as a symbol of cultural exchange and positive diplomacy. The past week saw hashtags such as:

#️⃣”IShowSpeed gives young foreigners a full-window view into China” (#甲亢哥给国外年轻人开了全景天窗#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed’s Shanghai livestream breaks Western filter on China” (#甲亢哥上海直播打破西方对中国滤镜#)

#️⃣”American influencer IShowSpeed amazed by stable wifi on China’s high-speed train” (#美国网红甲亢哥被高铁稳定网络震惊#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed praised deep tried tripe for being incredibly delicious” (#甲亢哥赞爆肚太好吃了#), or

#️⃣ “IShowSpeed bridges the cultural divide” (#甲亢哥弥合文化鸿沟#).

While in Chinese media, Watkins was lauded for shining a positive light on China, this message was also promoted on English-language social media, where he was praised by the Chinese embassy in the US (#驻美大使馆称赞甲亢哥中国行#), writing:

Post by Chinese Embassy in the US on X, March 26.

“This 20-year-old American internet star is bridging cultural gaps through digital means and creating new channels for foreign audiences to better understand China.”

So what exactly did IShowSpeed do while in China?

On March 24, Watkins livestreamed from Shanghai. He wandered around the city center, visited a KFC, danced with fellow streamers, stopped by a marriage market, ate noodles, played ping-pong, had hotpot, joined a dragon dance group and got acquainted with some traditional Chinese opera performance, and walked along the Bund.

On March 26, he streamed from Beijing, starting in Donghuamen before briefly entering the Forbidden City—dressed in a Dongbei-style floral suit. He later took a stroll around Nanluoguxiang and the scenic Houhai lake, rode a train, and finally visited the Great Wall, where he did backflips.

In his stream on March 28, Watkins traveled to Henan to visit the famous Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng, hoping to find a master to teach him kung fu. He trained with Shaolin monks—footage that quickly went viral.

Lastly, on March 29, he opened his own Weibo account and published his first post. On Douyin, he shared a video of his visit to Fuxi Mountain in Zhengzhou, featuring the popular “Stairway to Heaven” tourist spot.

On social media, many viewers were captivated by the content. One major talking point was the remarkably strong internet connection that allowed him to livestream for six-hour stretches without losing signal in Shanghai. (Though his Beijing stream started off patchier, the drop was minor.) For many, it symbolized the quality of China’s 5G services.

Foreign viewers also praised how safe, friendly, and clean the country appeared, and how his streams highlighted various aspects of Chinese culture—from everyday people to traditional arts and local cuisine.

🔹 Telling & Spreading China’s Stories Well

It is no wonder the success of the Jiǎkànggē livestreams is celebrated by Chinese official media in an age where China’s foreign communication aims to increase China’s international discourse power, shaping how the world views China and making that image more credible, more respectable, and more lovable.

That’s not just an observation — it’s an official strategy. Introduced by Xi Jinping in 2013, “Telling China’s Story Well” (“讲好中国故事”) is a political slogan that has become a key propaganda strategy for China and continues to be a priority in finding different ways of promoting Chinese culture — new ways of telling China’s story in the social media age – while countering Western dominant narratives about China.

In increasingly digitalized times, it is not just about telling China’s story well, but also spreading China’s message effectively — preferably through genuine and engaging stories (Cai 2013; Qiushi 2021).

Especially young, non-official ‘storytellers’ can make China’s image more relatable and dynamic. One major example, highlighted in a 2022 case study by Zeng Dan (曾丹), is Chinese influencer Li Ziqi (李子柒). You’ve probably heard of her, or seen snippets of her videos: she creates soothing, cinematic content depicting China’s countryside lifestyle, focused on cooking, crafts, and gardening. With 26 million followers on YouTube, Li Ziqi became a viral sensation who successfully communicated an authentic and appealing ‘China story’ to a broad global audience.

Li Ziqi in one of her YouTube videos.

Although the calm and composed Li Ziqi and the loud, chaotic IShowSpeed couldn’t be more different, they have some things in common: both have large international fanbases, including their millions of YouTube subscribers; they offer perspectives that differ from Chinese state media or official channels; and they have the capacity not just to tell China’s story well, but to spread it effectively through videos and livestreams.

🔹 Spontaneous Stream or Scripted Propaganda?

IShowSpeed’s China streams have triggered a wave of responses from fans and viewers, sparking discussions across international social media and even making newspaper headlines.

In English-language online media spheres, there appear to be a range of perspectives on Watkins’ China trip:

📌 One prominent view—also echoed by various foreign influencers on YouTube and other platforms—is that IShowSpeed’s visit counters “Western media lies” about China and has successfully shown the “real China” through his livestreams. The Shanghai-based media outlet Radii claimed that “IShowSpeed’s China Tour is doing more for Chinese Soft Power than most diplomats ever could.”

📌 Others challenge this narrative, questioning which dominant Western portrayals of China IShowSpeed has actually disproven. Some argue that the idea of China being a “bleak place with nothing to do where people live in misery” is itself a false narrative, and that presenting IShowSpeed’s livestreams as a counter to that is its own form of propaganda (see: Chopsticks and Trains).

📌 There are also those who see Watkins’ trip as a form of scripted propaganda. To what extent were his livestreams planned or orchestrated? That question has become one of the central points of debate surrounding the hype around his visit.

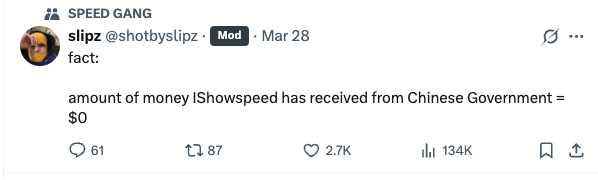

These rumors have been addressed by cameraman Slipz (@shotbyslipz), who took to X on March 28, 2025. Slipz posted that the team is “(..) not making political content, not any documentary and no journalism,” and later added: “Fact: amount of money IShowSpeed has received from Chinese Government = $0.”

But does the fact that IShowSpeed did not receive money from the Chinese government mean that it wasn’t also a form of China promotion?

➡️ Organized — it definitely was. Any media trip in China has to be. IShowSpeed would have needed a visa, he had translators with him, and throughout the streams it’s evident that local guards and public security officers were present, walking alongside and helping to keep things under control, especially in crowded areas and at major tourist spots — from Nanjing Road in Shanghai to an entire group of guards seemingly accompanying the entourage in the Forbidden City.

One logistical “advantage” to his visit was the fact that YouTube is blocked in China. While some Chinese fans do bypass the Great Firewall to access the platform, IShowSpeed remains far less known in China than in many other countries — a factor that likely contributed to how smoothly the streams went and helped prevent chaos. The team also launched a Douyin account during the trip, where he now has over two million followers. (To stream directly to their 37 million followers on YouTube, Watkins’ team either needed a VPN to access WiFi or had arranged roaming SIM cards to stay connected.)

➡️ Was it staged? Many parts clearly weren’t: casual public conversations, spontaneous barber visits in both Shanghai and Beijing (with barbers looking unsure of how to handle the situation), and wholesome fan encounters. There was even a moment when Watkins walked into a public restroom and forgot to mute the sound.

But other parts of the trip were undeniably staged — or at least framed to appear spontaneous. When visiting a marriage market in Shanghai, for instance, two actors appeared, including one woman with a sign stating she was looking for someone “capable of doing backflips.”

When Watkins took a “random” ride in what was described as the fastest car in China — the Xiaomi SU7 Ultra — the vehicle appeared to be conveniently parked and ready.

Similarly, when the streamer “ran into” Chinese-American TikTok influencer Miles Moretti (李美越) in Beijing, it turned out to be the person who would give him the now-iconic bright Dongbei flower suit and accompany him on his journey.

The ping-pong, the kung fu, the Peking opera, the hotpot, the Forbidden City tour — it all plays into the kinds of experiences that official channels also like to highlight. While likely planned by Watkins’ team in coordination with local partners, it was all far more orderly and tourism-focused than, for example, Watkins’ chaotic visit to the Netherlands.

Watkins and his entourage were also well-informed about the local dos and don’ts. At one point, Watkins even mentions “following the rules,” and when Moretti tells him mid-stream that “somebody very important lives on our left,” Watkins asks “Who?” — but the camera zooms out and the question goes unanswered, suggesting they may have been reminded that certain names or topics were off-limits (judge the moment for yourself here).

The livestream didn’t always go exactly the way Watkins wanted, either. When he attempted to take more random walks around the city, the crew appeared to be informed that some areas were off-limits, and he was asked to return to the car to continue the trip (clips here and here).

🔹 The “Nàge” Song

One major talking point surrounding IShowSpeed’s China livestreams was “the N-word.” No, not that N-word — but the Chinese filler word “nàge” or “nèige” (那个). Like “uhm” in English or “eto” in Japanese, “nàge” is a hesitation marker commonly used in everyday Mandarin conversation. It also functions as a demonstrative pronoun meaning “that.”

The word has previously stirred controversy because of its phonetic resemblance to a racial slur in English. In 2020, an American professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business was even temporarily suspended after using the word during an online communications class — some students misunderstood its context and took offense.

The word — and the song “Sunshine, Rainbow, White Pony” (阳光彩虹小白马) by Chinese singer Wowkie Zhang (大张伟), which repeatedly features the word nàge in its chorus — popped up multiple times during Watkins’ trip. The catchy tune essentially became the theme song of his visit.

The first nàge moment actually already appeared within the first five minutes of Watkins’ Shanghai stream, when a Chinese comedian approached him on the street, trying to recall a joke. “What?!” Watkins reacted, with laughter in the background. “That’s not a joke, you said n**! It’s my first five minutes in China!” he exclaimed, before patting the man’s back in a friendly gesture, clearly not offended.

🔄 It resurfaced again within the first hour when Watkins visited a marriage market and one of the performers sang the Wowkie Zhang song. Watkins initially acted shocked, then demanded they sing it again — only to burst out laughing and start singing along.

🔄 Later, he sang the song again with a street saxophonist and encouraged others to join in.

🔄 At other moments, he played up the drama again, feigning anger when a crowd broke into the chorus, and it became a recurring gag throughout the streams.

These incidents all seem staged. One of the main reasons Watkins is known to many netizens in China is because of an older video clip showing his exaggerated reaction to the nàge song — dating back to at least 2022. So while it may have looked spontaneous, Watkins was already familiar with the word and the viral song long before his China trip.The attention given to the nàge ‘controversy’ was likely amplified for views and engagement.

While Watkins was clearly in on this part of the show — as with others — he also seemed genuinely, and at times amusingly, unaware of many things in China. He repeatedly referred to RMB as “dollars,” mistook elderly women for retired YouTube streamers, and even assumed that a woman livestreaming near the Forbidden City was reading his chat and trying to collaborate with him — although she seemed totally uninterested and was just minding her own business.

🔹 A Win-Win Situation

In the end, IShowSpeed’s visit highlighted two sides effectively doing their job. Watkins and his team successfully arranged a YouTube trip that generated high ad revenue, attracted millions of new subscribers, and boosted his brand and global fame.

On the Chinese side, there was clearly coordination behind the scenes to ensure the trip went smoothly: avoiding controversy, ensuring safety, and showcasing positive aspects of Chinese culture. From traditional opera and kung fu to ping pong, IShowSpeed’s content gave center stage to the kinds of cultural highlights that align closely with China’s official narratives and tourism goals. Even if the government didn’t pay the YouTuber directly, as his team has emphasized (and there’s no reason to doubt them), the trip still fit seamlessly into China’s soft power strategy.

IShowSpeed’s China visit has created a unique media moment that resonates for several reasons: it’s the encounter of a young modern American with old traditional China; it is a streamer known for chaos visiting a nation known for control. And it brings different benefits to both sides: clicks and ad revenue for IShowSpeed, and free foreign-facing publicity for China.

No, IShowSpeed didn’t undo years of critical Western media coverage on China. But what his visit shows is that we’ve entered a phase where China is becoming more skilled at letting others help tell its story — in ways that resonate with a global, young, online audience. He didn’t do “God’s work.” He simply did what he always does: stream. And with China’s help, he streamed China very well.

There’s so much more I want to share with you this week — from Chinese reactions to the devastating Myanmar earthquake, to a recent podcast I joined with Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf (link in Dutch, for those interested). But it also happens to be my birthday today, and I’m really hoping to still grab some birthday hotpot — so I’ll wrap this up here. I’ll keep you informed on the other trends in the next newsletter.📨.

Best,

Manya

(@manyapan)

References:

Cai, Mingzhao 蔡名照. 2013. “Telling China’s Stories Well and Spreading China’s Voice: Thoroughly Studying and Implementing the Spirit of Comrade Xi Jinping’s Important Speech at the National Conference on Propaganda and Ideological Work [讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音——深入学习贯彻习近平同志在全国宣传思想工作会议上的重要讲话精神].” People’s Daily 人民日报, October 10. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1010/c1001-23144775.html. Accessed March 29.

Qiushi 求是网. 2021. “Xi Jinping: Telling China’s Story Well, Spread China’s Voice Well [习近平:讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音].” Qs Theory, June 6. http://www.qstheory.cn/zhuanqu/2021-06/02/c_1127522386.htm. Accessed March 29.

Zeng Dan 曾丹. 2022. “How to Tell China’s Story Well: Taking Li Ziqi as an Example [如何讲好中国故事——以李子柒为例].” Progress in Social Sciences 社会科学进展 4 (1): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.35534/pss.0401002.

What’s Featured

Quite terrifying and interesting, as this trending story touched upon so many different issues.

What started as a single snarky comment on Weibo spiraled into an online witch hunt, exposing not just some dark sides of online Kpop fandom but also, most importantly, the vulnerabilities in China’s digital privacy.

Read the story, the latest by Ruixin Zhang 👀

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral4 months ago

China Memes & Viral4 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained