China Society

Weibo Watch: Going the Wrong Way

About how one delivery driver’s plea for leniency shed light on challenges and struggles faced by millions of food delivery workers, and more must-know trends.

Published

1 year agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #35

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Going the wrong way

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Noteworthy – Young woman’s lonely death in rented apartment

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Fan Zhendong’s pluche toys

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Ren Zhiqiang’s Weibo exit

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – Fandom-ization

Dear Reader,

“Apology! Apology!” Dozens of delivery drivers chanted, standing together in front of Hangzhou’s Xixi Century Square. The group of workers, mostly men, had gathered in front of the complex after learning about an incident that took place just hours earlier.

One of their colleagues, a young delivery driver for the Meituan platform named Wang, had accidentally damaged a fence while trying to enter the complex to deliver a food order on August 12. The security guard stopped him and allegedly demanded 200 yuan ($28) in compensation. Onlookers captured a video showing Wang kneeling before the guard, pleading for leniency. He could not afford the fee nor the kerfuffle—it was peak lunch hour, and he needed to deliver his order on time.

The image that went viral on the afternoon of August 12.

The incident immediately went viral in WeChat groups.1 The image of the delivery driver on his knees, hands in his lap, helplessly looking up at the security guard, resonated with many delivery workers, sparking anger. Members of the delivery community decided to gather at the scene and protest the way their colleague had been treated.

As more delivery drivers arrived, tensions escalated (video). At least twenty police officers, including a specialized police unit, were called in to deescalate the situation, and the security guard was rushed away for his own safety.

That same night, local authorities issued a notification about the incident, urging people to remain calm and show more tolerance and understanding during these blazing hot summer days.

But the simmering tension beneath the surface runs deeper than just the summer heat.

In recent years, many viral videos have captured the hardships faced by Chinese food delivery workers, who endure scorching heat, heavy rain, and thunderstorms to deliver their orders. On August 21, a delivery driver in Pingyang collapsed while picking up a food order at a restaurant but insisted on completing the delivery (he was eventually taken to the hospital by ambulance). Other videos on platforms like Douyin show delivery riders breaking down during work.

The pressure they face is real, and the work they do is intense. China’s main food delivery platforms, Meituan and Ele.me, backed by tech giants Tencent and Alibaba, employ a combined 10 million delivery drivers. Their daily work is monitored by algorithmic management tools. The workload is high, the overwork is severe, the income is low, and the conditions are often unsafe.

Most of these workers are lower-educated migrant workers from rural areas who were already in vulnerable positions before taking these jobs. They face challenges such as limited job opportunities, inadequate medical care, poor nutrition, and sometimes language barriers or social alienation in China’s urban jungle.2 The digital control makes their work stressful—a late order or bad review can cost them income.

Recent studies show that these factors make China’s food delivery drivers highly susceptible to anxiety and depression. One study focusing on urban delivery drivers in Shanghai found that 46% of the drivers surveyed reported anxiety symptoms, and 18% experienced depression.3

While the recent Hangzhou incident and other viral moments have drawn attention to the stressful working conditions and weak social status of China’s food delivery workers, a new Chinese movie presents a different perspective on the gig economy.

One of the movie posters for Upstream (2024).

Upstream “逆行人生” (Nìxíng Rénshēng), a movie by director and star actor Xu Zheng (徐峥), was released on August 9. The story revolves around former programmer Gao Zhilei—played by Xu himself—who loses his job and savings. To support his family and ill father, he takes up a job as a delivery worker to survive.

The Chinese title of the movie, 逆行人生, translates to “a life against the current.” The term 逆行 (nìxíng) literally means ‘to go the wrong way’ or ‘to move in the opposite direction,’ and it has been translated as ‘upstream’ in this case. Since early 2020, Chinese state media have used the term 逆行者 nìxíngzhě, “those going against the tide” to refer to frontline workers and everyday heroes who made significant contributions or sacrifices for society, particularly during the pandemic or in emergencies such as forest fires.

Although Upstream does highlight some of the struggles faced by Chinese gig workers, it is largely a feel-good movie that avoids a deeper exploration of the marginalized status and precarious work conditions of gig workers. The title and story align with the narrative promoted by official media about China’s food delivery workers, especially during the pandemic when their work was extra demanding. Instead of lobbying for better labor conditions, they are praised as heroic and altruistic; as noble national heroes who act for the greater good. As one driver quoted in a study by Hui Huang put it: “They treat us as heroes in the media, but as slaves in reality.”4

This sentiment also plays a role in the public’s reception of Upstream, as discussed in a recent article by Sixth Tone. Many feel that the film exploits the struggles of China’s gig workers for entertainment and profit rather than genuinely advocating for their rights and well-being. Turning such harsh realities into a feel-good narrative is seen by some as “the wrong way” rather than “upstream.” Some have even described it as “rich people acting poor and making the poor pay for it.”

One Zhihu user placed the actual film poster next to an alternative version featuring delivery driver Wang in a vulnerable, knee-down position, which powerfully symbolizes how many delivery drivers perceive their weak status in society. The official poster says, “August 9 – auspicious/timely delivery,” while the alternative poster states, “August 12 – delivery not possible.”

Photo uploaded by 芒果味跃迁引擎 on Zhihu

However, there is an upside to the heightened attention on China’s food delivery workers: increased awareness. For example, the absurdity of relying on algorithms for their work is now sparking important discussions.

Delivery algorithms put pressure on riders by calculating precise delivery times based on ideal conditions, leaving little room for traffic delays, staircases, extreme weather, or restaurant preparation times. Riders can get caught in “algorithm traps” (算法陷阱) because the faster they work, the stricter the algorithm tightens delivery windows, and they may face penalties or reduced earnings if they fail to meet the expected times.

The fact that, through Upstream and the Hangzhou incident, people are now acknowledging the pressure that Meituan and Ele.me drivers face under such digital systems is already a big improvement from 2019, when debates centered on whether or not you should say “thank you” to acknowledge the service provided by delivery drivers.

“Maybe some parts of this film don’t fully connect with reality,” author Yan Lingyang (晏凌羊) wrote on Weibo about Upstream: “But under the current system, I think it’s already quite daring. It reflects various issues such as the economic downturn, housing bubbles, corporate burnout [involution], low wages for grassroots workers, lack of rights protection, and algorithm traps.”

Chinese blogger Cui Zijian (崔紫剑) recently also spoke out against the exploitation of drivers by platform companies, arguing that algorithms should be improved and suggesting that delivery riders be included in unions.

While the reception of Upstream and the Hangzhou delivery driver protest might seem to indicate that things are going the wrong way, the increased awareness actually points in the right direction—toward greater understanding of the challenging situation faced by millions of workers.

I’d love to dive deeper into topics such as these that are so relevant in everyday society and show how digital platforms impact the lives of people. Since I’m always reporting the latest trends, it often leaves little room for the more in-depth articles and overviews I’d love to write for you about the issues behind China’s hot topics & tech developments. Because of this, I’ve decided to gradually shift my focus toward deeper dives instead of shorter trend articles for What’s on Weibo. I’ll still provide timely updates on the latest trends through the Weibo Watch newsletter. I’m currently brainstorming how to make this transition, and I’ll keep you involved as I work on continuing to deliver insightful content. Finding the right balance between covering current trends and providing more contextual analyses can be challenging, but I can’t complain—thankfully, no algorithms are chasing me.

Miranda Barnes has contributed to the compilation and interpretation of the topics featured in this week’s newsletter. Ruixin Zhang has authored the insightful fan culture article, and contributed to the word of the week. As always, if you have any observations or ideas you’d like to share, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

1 The initial story that went viral in WeChat groups (links of screenshots) claimed that the delivery driver was a woman, and that the security guard had forced her to kneel. This detail intensified the outrage. However, it was later revealed that the driver was actually a thin, male worker who knelt voluntarily, in hopes of speeding up the process.

2 See Peng, Yuxun, et al., “Status and Determinants of Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression among Food Delivery Drivers in Shanghai, China,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20 (2022): 1; and Hui Huang, “Riders on the Storm: Amplified Platform Precarity and the Impact of COVID-19 on Online Food-delivery Drivers in China,” Journal of Contemporary China 31, no. 135 (2022): 351, 363.

3 See Peng, Yuxun, et al., “Status and Determinants of Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression among Food Delivery Drivers in Shanghai, China,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20 (2022): 10.

4 See Huang Hui, “Riders on the Storm: Amplified Platform Precarity and the Impact of COVID-19 on Online Food-delivery Drivers in China,” Journal of Contemporary China 31, no. 135 (2022): 363.

What’s New

Ping Pong Fandom | The table tennis final between Chen Meng and Sun Yingsha in Paris exposed troubling fan dynamics, sparking discussions on the clash between fandom culture & the Olympic spirit. Read our latest on the influence of fandom culture in Chinese table tennis 🏓 🔗

The Big Olympic File | Before the Paralympics will start on August 28, time to reflect on what happened during the Olympics. We reported and wrapped it up! Capturing all the must-know medals and online discussions happening on the sidelines of the Olympics, here’s the What’s on Weibo China at Paris 2024 Olympic File.

Medals and Memes | The 2024 Paris Olympics captivated Chinese social media, not just for the gold medal victories but also for the many moments that unfolded on the sidelines. Here are the 10 most popular ones.

The Human Bone Controversy | Chinese online media was flooded with 404 errors earlier this month as many of the articles published about the human bone scandal—where the Chinese company Shanxi Aorui illegally acquired thousands of corpses to produce bone graft materials sold to hospitals—were taken offline. From 2015-2023, Shanxi Aorui forged body donation registration forms and other documents to purchase corpses from hospitals, funeral homes and crematoriums to produce bone implant materials sold to hospitals.

What’s Trending

🐒 Black Myth Wukong

A Chinese game that has been in development for over four years is top trending on Weibo this week. More than that: it’s a national sensation. Black Myth: Wukong (黑神话悟空) was officially released on August 20, surpassing all expectations. Within an hour of its release, it topped the “Most Played” list on Steam, with over 2 million concurrent players.

Developed by Game Science, a startup founded by former Tencent employees, Black Myth: Wukong draws inspiration from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. This epic tale, filled with heroes and demons, follows the supernatural monkey Sun Wukong as he accompanies the Tang dynasty monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to India to obtain Buddhist sūtras (holy scriptures). The game focuses on Sun Wukong’s story after this journey. Black Myth: Wukong has been such a massive success that anything associated with it is also going viral—a merchandise collaboration with Luckin Coffee sold out instantly.

🥇 Olympic Heroes Hailed at Home

China’s Olympic champions, including Quan Hongchan (全红婵), who we also discussed in our last newsletter, have received warm welcomes home as their hometowns were transformed into temporary pilgrimage sites, complete with medal ceremonies and huge posters. There have been many touching moments during the champions’ return. For example, Boxing Gold medalist Wu Yu jumped into her mom’s arms and cried like a little kid after returning from her Paris adventure.

In addition to the warm receptions in their hometowns, the champions were also honored in Beijing at the Great Hall of the People, where Xi Jinping met with the athletes on August 20 and praised them for their performance and sportsmanship throughout the Paris Games. A related hashtag has garnered 360 million views on Weibo ( #中国体育代表团总结大会举行#)

🚨 Magic Carpet Ride Gone Wrong

The “magic carpet ride” at the popular Detian Waterfall scenic area in Guangxi’s Chongzuo drew significant attention on social media earlier this month after a malfunction led to tragic consequences. This attraction, designed to transport visitors up the mountain as they sit backward on a moving belt, suddenly malfunctioned on August 10, causing passengers to slide uncontrollably downwards (here you can see how the attraction normally operates).

The accident resulted in one tourist’s death and injuries to 60 others. A joint investigation team was established to determine the cause of the incident. Preliminary findings suggest that a steel buckle at the belt’s joint broke, causing the belt to rapidly slide downward. With passengers spaced about a meter apart on the conveyor belt, the sudden movement led to collisions, with some individuals being crushed, particularly at the lower end. Those responsible for the attraction’s operation and maintenance have been detained in accordance with the law for their roles in the incident, which will be further investigated.

🍵 Eileen Gu Controversy

Whether it’s her athletic career or personal life, Eileen Gu (谷爱凌) always seems to find herself trending in China. The American-born freestyle skier and gold medalist who represented China at the 2022 Beijing Olympics sparked discussions during the Paris Olympics due to her connection with Léon Marchand, the renowned French Olympic swimmer. Marchand faced significant backlash on Chinese social media after being accused of ignoring a handshake from Team China’s coach Zhu Zhigen (朱志根). A brief video of the incident went viral, showing the Chinese coach approaching Marchand to congratulate him, only for Marchand to seemingly ignore him and walk away.

Amid the controversy, netizens noticed that Gu, who had previously interacted with Marchand online, deleted her comments on his Instagram, including a compliment on his latest Olympic victory (“incredible”) (#谷爱凌删了给马尔尚的所有ins评论#). However, when videos surfaced of Gu dancing closely with Marchand, she was accused of being two-faced or insincere. While some initially saw her deletion of the interactions as a patriotic gesture, many now believe she was simply being opportunistic.

But Gu is clapping back at her haters, suggesting that she can never please everyone. When someone called her out for being “a traitor” to her country, Gu reportedly replied, “Which one?” The issue of Gu’s nationality has been a somewhat sensitive topic since she first represented China, with many questioning whether she holds a Chinese or American passport (as China does not recognize dual nationality). Gu’s previous statement, “I’m American when in the US and Chinese when in China,” has also triggered dissatisfaction among Chinese audiences. On Instagram, she has now confronted her haters: “In the past five years, I’ve won 39 medals representing China and spoken out for China and women on the world stage. What have the haters done for the country?”

💍 New Marriage Rules

A revised draft regulation on marriage registration introduced by China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs last week has sparked significant online discussion. One notable change is that couples will no longer need their hukou, or household register, to get married. Traditionally, this document is often held by parents, meaning that those who wish to marry had to obtain it—essentially seeking parental approval. By removing this requirement, the process is simplified, giving individuals more freedom to marry, even if their parents disagree.

However, the draft regulation is drawing criticism, primarily due to the inclusion of a 30-day cooling-off period for divorce. This cooling-off period (“冷静期”) allows either party to withdraw their divorce application within 30 days of filing. Although introduced in a draft as early as 2018, it continues to generate debate. Many feel that while the revision appears to grant more freedom in marriage, it restricts the freedom to divorce in a timely manner. Some say this is like a “loose entry, strict exit” (宽进严出) policy, similar to Chinese university admissions. One popular comment called it “fake freedom.” The draft regulation is open for public feedback until September 11.

🚴 Discussions over Cycling Boy’s Death

A tragic incident in Hebei has sparked significant online discussions. In Rongcheng County, an eleven-year-old boy who was cycling with his father in a group of cyclists fell down and was run over by a car coming from the opposite direction. A dashcam video captured the group riding in the middle of the road, leaving the oncoming vehicle with little room or time to avoid the collision. The boy succumbed to his injuries shortly after the accident.

The incident has led to broader debates about the father’s responsibility. According to road safety laws, the eleven-year-old should not have been cycling on a public road, especially not in the middle of it. The situation is further complicated by reports that people had previously warned the father about the dangers of bringing his young son on high-speed cycling trips, warnings which he allegedly ignored. Although the father initially attempted to shift the blame onto the driver for speeding, public opinion has largely condemned him for being irresponsible, with devastating consequences.

🇨🇳 Chinese Flag Controversy

A hotel in Paris, part of a Taiwanese chain, became the center of online attention this August after it failed to include the Chinese flag in its Olympic-themed decorations. The issue was brought to light by a Chinese influencer who posted a video accusing the Evergreen Laurel Hotel (长荣桂冠酒店) of refusing to display the Chinese flag, even after the influencer offered to provide one. The incident sparked significant backlash, leading domestic travel platforms like Ctrip and Meituan to delist the hotel’s booking options, including those at its Shanghai location. The hotel eventually issued an apology, but many netizens found it too vague, as it did not directly address the flag incident, instead focusing on general dissatisfaction with their decorations. The Chinese Embassy in France has since commented on the issue, expressing support for Chinese people, both at home and abroad, in their efforts to “remain united and uphold patriotic values.”

What’s Noteworthy

The WeChat account Zhenguan (贞观) reported on August 16 about a tragic incident involving a 33-year-old woman from a small, impoverished village in Ningxia who died alone in her rented 30th-floor apartment in Xi’an. Her body was not discovered for a long time, and by the time it was found, it had decomposed to the point of being unrecognizable. In the article, titled “A Women From Out of Town Died in the Apartment I Rented Out” (“一个外地女孩,死在了我出租的公寓”), which has since been deleted, a landlord shares their story of how they discovered the single young woman had died inside the studio apartment. The article paints a picture of a once-bright rural girl who became disillusioned as the competitive educational system and the pressures of city life crushed her spirit. The woman, who depended on her family’s financial support, hadn’t ordered or cooked any food for nearly twenty days since she was last seen in May, suggesting she most likely starved to death in her apartment.

The article quickly went viral over the weekend. The incident, which allegedly took place during the summer, resonated with people as they began filling in the gaps of the story with their own interpretations. They felt for the woman, who had worked hard in life but had found herself unable to live up to expectations. Some saw the young woman’s story as a tragic reflection of the struggles in contemporary Chinese society. Some blamed city life, others blamed rural culture. But many also doubted the story’s authenticity.

After Chinese media outlets like Zhengzai Xinwen (正在新闻) began investigating the matter, it was revealed that some details in the story were inaccurate. The incident did not occur in Xi’an but in Xianyang. People from the woman’s hometown mentioned that she was socially withdrawn and may have struggled with mental health issues, though she was never formally diagnosed. Local police did confirm that the incident is real and that it is still under investigation by a local branch of the Xianyang Public Security Bureau. Regardless of the exact circumstances, the woman’s story has struck a chord, with one popular comment on Weibo stating: “There are countless others like her in society who are experiencing the same struggles. No matter what you’re going through, I hope you don’t give up on life.”

What’s Popular

This summer’s Olympic fever in China has been evident across various e-commerce platforms. Whether it was the sudden popularity of Zheng Qinwen’s tennis skirt or the craze over diver Quan Hongchan’s ugly animal slippers, Chinese consumers have eagerly embraced Olympic-themed shopping.

Recognizing the influence of athletes during and after the Olympics, brands have tapped into their potential by launching various collaborations. A particularly successful example is the plush paddles endorsed by Olympic table tennis star Fan Zhendong (樊振东). The 27-year-old national table tennis player, often referred to as the “National Ping Pong God” (国乒男神), not only clinched double gold in Paris but also endorses several brands, including the British Jellycat brand, which created the plush paddle toys.

One popular video shows Fan playing table tennis with the plush paddle toy, which quickly sold out after his Olympic victory. The toy was restocked twice in three days before selling out again. Many commenters praised the toy for being so cute, and in light of Wang Chuqin’s now-famous broken paddle incident, others joked that it’s a good thing the plush paddles are unbreakable.

What’s Memorable

China’s well-known political and social commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进) has been noticeably absent from Chinese social media for about a month. The former editor-in-chief of the Global Times has not posted on his account since July 27—an extraordinary, unannounced, and unexplained pause from his typically daily social media activity. In light of Hu’s sudden silence, we take a look back eight years into the What’s on Weibo archive, when another social media commentator and real estate tycoon, Ren Zhiqiang (任志强), abruptly went silent, and his account subsequently disappeared.

Weibo Word of the Week

Fan Cultured | Our Weibo word of the week is ‘fan-cultured’ or ‘fandom-ization’ (fànquānhuà 饭圈化). While fànquān 饭圈 literally means “fan circle,” the suffix huà 化 is generally used to indicate a process of transformation or turning into something, similar to the “-ization” suffix in English.

The term fànquānhuà 饭圈化 refers to the recently much-discussed phenomenon where something—often outside the realms of entertainment—receives passionate support from people who begin to form online fan circles around it, changing the dynamics in ways that resemble the relationships between celebrity idols and their fans.

A recent example of something being “fan-cultured” or “fandom-ized” is how fans have started to form extremely strong communities around China’s table tennis stars, defending them as if they were idols. This fan behavior has been criticized by Chinese authorities, who see it as toxic fan culture that goes against the Olympic spirit (read more).

But “fandom-ization” goes beyond sports. There are also strong fan club dynamics surrounding Chinese pandas. Even inanimate objects can become “fan-cultured.” For example, the Little Forklift Truck (小叉车) that was part of the construction of the Huoshenshan emergency specialty field hospital during the early days of the Covid crisis. The construction process was live-streamed, and millions of viewers found the little truck—working tirelessly around the clock—so cute and brave that it became “fan-cultured.”

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Memes & Viral

Nanchang Crowd Confuses Fan for Knife — Man Kicked Down and Taken Away

An unfortunate misunderstanding led to one innocent man being the only person injured in a crowd of thousands.

Published

2 months agoon

October 5, 2025

On the evening of October 1st, National Day and the start of a week-long holiday, Nanchang was celebrating with a spectacular fireworks/drone show, drawing an enormous crowd of people (see video).

But the fireworks weren’t the only thing drawing attention. One man on Nanchang’s crowded Shimao Road caught bystanders’ eyes.

He was shirtless, strongly built with a visible tattoo, and was waving a pointed object while loudly shouting something that sounded like, “I’ll kill you! I’ll kill you!”

At first, the people around him seemed unsure of what to do, keeping their distance and too afraid to approach. A large crowd formed but stayed back.

Then, a brave young man in red rushed forward and snatched the pointed object from his hand, while another young man leapt in with a flying kick that knocked him to the ground.

Several others then joined in, working together to restrain the man, as onlookers surrounded the scene and held him there until police arrived and took him to the station.

Soon, videos of the incident spread online (see video here), and rumors quickly surfaced that the man had been trying to attack people with a knife.

But that all turned out to be one major misunderstanding.

The next day, local police clarified what had actually happened, followed by an explanation from the man himself.

The man in question, a 31-year-old local second-hand car dealer named Li, had come to see the fireworks together with his family, including his sisters and three nephews.

Because of the very hot weather, he had taken off his shirt and was cooling himself with a 10-yuan folding fan he had just bought along the way.

After the show, while walking back, Li realized one of his nephews was missing and searched for him, calling out in his local dialect: “Where’s my kid? Where’s my kid?” (“我崽尼 我崽尼” wǒ zǎi ní).

Bystanders misheard this as “我宰你 我宰你” (wǒ zǎi nǐ, wǒ zǎi nǐ, “I’ll kill you, I’ll kill you”) and mistook his folding fan for a machete.

Meanwhile, Li couldn’t understand why people around him were avoiding him and keeping their distance from him while he was searching for his nephew (see that moment here, also see more footage here). People were watching him, and recording the scene from a distance.

Before Li realized what was happening, the fan was snatched from his hands and he was violently kicked. A crowd swarmed him, beat him, and pushed him to the ground.

The police then detained him, and it wasn’t until the early hours of October 2, after thorough questioning, that he was finally released.

“I’m still confused about it,” Li said the next day. Holding the fan up to the camera, he asked: “Can a fan like this really scare people? I don’t understand — I just got beaten for nothing.”

Mr Li in his video, showing the fan he bought for 10RMB/$1.4 at the Nanchang fireworks.

Some commenters remarked that out of the 1.2 million people who were out in Nanchang that night, he was the only one injured.

Li seems to be doing ok apart from a sore backside and a puzzled mind, and his nephew apparently is also safe and well.

The bizarre misunderstanding has sparked widespread banter online, with people now referring to Li as “Nanchang Brother Fan” (南昌扇子哥).

“I’m dying of laughter. It’s both tragic and hilarious,” one Douyin user wrote, while others simply called the situation “so drama” (抓马 zhuāmǎ): “I’m not supposed to laugh, but I can’t help it.”

Some also noted that they understood why people at the scene mistook Li for a criminal: “At night, a guy with tattoos, holding a long stick-like object, shouting loudly all the way, what would you think?”

All joking aside, the public’s response on such a crowded night — when so many people gathered together, potentially making a tempting target for those with bad intentions — shows a heightened sense of vigilance. Unlike the U.S., where gun violence is more common, shootings are rare in China. But random stabbings have increasingly made headlines.

For Nanchang in particular, a stabbing incident that shocked the nation had taken place only weeks earlier: a 19-year-old woman was attacked and stabbed more than ten times by a 23-year-old man she did not know, and later died from her injuries.

But there have also been other recent cases, from Wuhan to Leiyang. And in 2024 especially, a spate of stabbing incidents shocked the country. In Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, a mass stabbing left eight people dead and 17 others injured.

The positive takeaway from this entire mix-up is that the quick action of the crowd — despite their wrong assessment of the situation — shows that people weren’t afraid to step in for the sake of public safety.

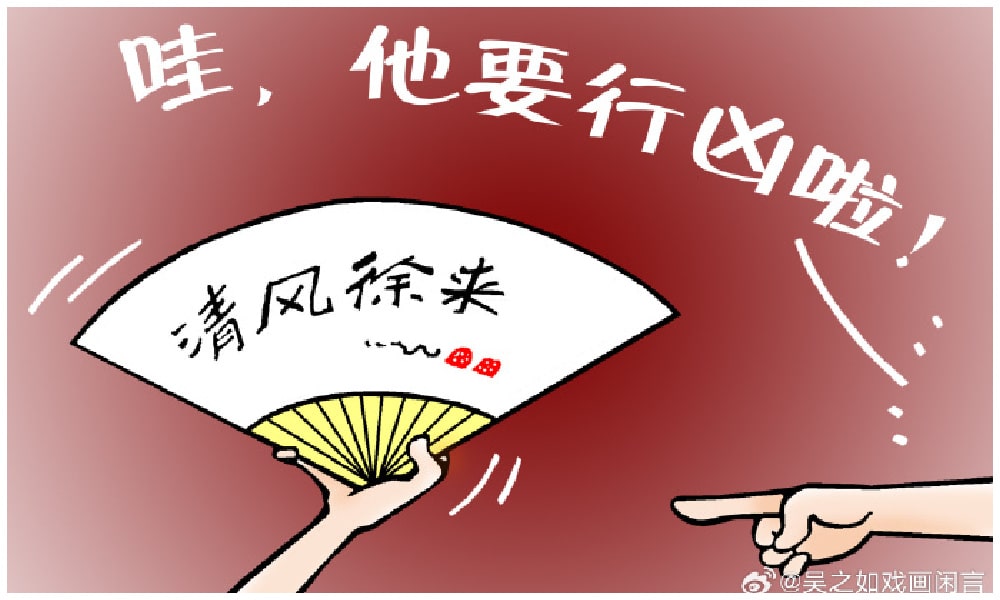

But others claim the exact opposite is true. Illustrator and commentator ‘Wu Zhiru’ (吴之如), former editor at Zhenjiang Daily, saw the incident as an example of toxic herd mentality. He posted an illustration of a fan being held up with the characters 清风徐来 (qīng fēng xú lái, “a cool breeze slowly blows”), an idiom to describe a pleasant atmosphere. A finger from the right points at the fan-holder, saying “Look, he’s gonna commit violence!” (“哇,他要行凶啦!”)

Wu Zhiru warns against panic-driven mob mentality and wonders why the first man, who snatched the “knife” from Li’s hands, did not stop the crowd from attacking Li as soon as he discovered that he had snatched away a fan and not a blade. Drawing historical parallels to the Cultural Revolution, Wu argues that people are sometimes so set on doing the “heroic” thing that they hesitate to correct misunderstandings once better information is available — a mindset that can lead to serious, harmful consequences.

For Li himself, despite the unfortunate night he had, the situation has actually brought him some unexpected fame and extra attention for his second-hand car dealership, which undoubtedly makes his boss happy (in a very recent livestream, Li was praised for being kind and loyal).

Many netizens also argued that the real lesson to draw from this ordeal is the importance of speaking proper standard Chinese. Some even framed the incident as “The Importance of Mandarin” (论普通话的重要性), pointing out that the whole problem began because Li was misunderstood while speaking dialect.

Image posted on Weibo in support of the “fan-waving brother.” The character on the fan says “tolerate.”

Others joked that the misunderstanding was just a grave injustice to shirtless men everywhere, writing: “From now on, the world has one less sincere guy who goes shirtless in the streets. He’ll never be the same again.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

China’s National Day Holiday Hit: Jingdezhen’s “Chicken Chop Bro”

From viral street food vendors to China’s donkey crisis and new eldercare services, here’s this week’s Weibo highlights in What’s on Weibo’s China Trend Watch.

Published

2 months agoon

September 30, 2025

🔥 What’s Trending in China This Week? Stay updated with China Trend Watch by What’s on Weibo — your quick overview of what’s trending on Weibo and across other Chinese social media, curated by Manya Koetse.

What’s inside:

- 1. Jingdezhen’s “Chicken Chop Bro” Becomes Nationwide Meme

- 2. China’s 2025 Golden Week Travel Trends

- 3. China Faces Donkey Shortage Crisis

- 4. Word of the Week: “Ride-hailing for Relatives” 亲属打车 Qīnshǔ Dǎchē

- 5. What’s Inside at a Glance

1. Jingdezhen’s “Chicken Chop Bro” Becomes Nationwide Meme

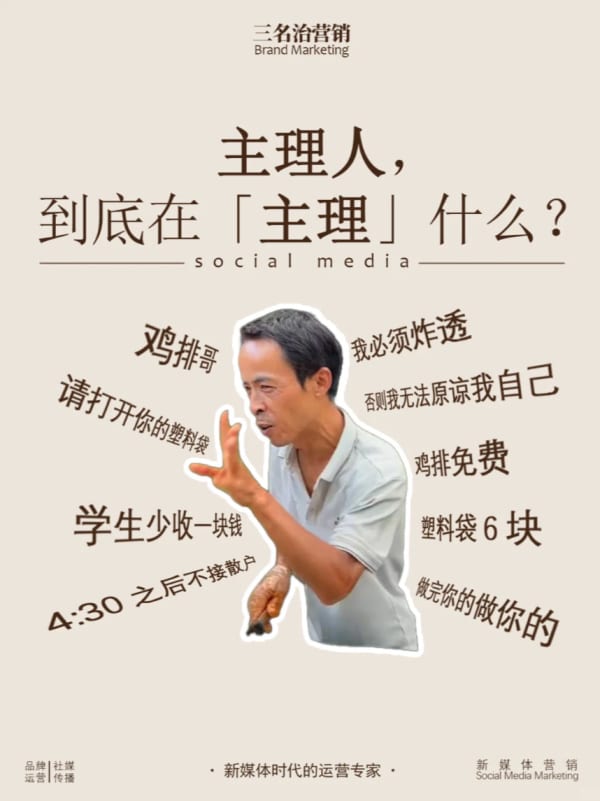

From Beijing to Zibo, every now and then, food stall vendors go viral — for their charm, their uniqueness, and most of all, their tasty food. The star of this moment is 48-year-old Li Junyong (李俊永), who runs a small fried chicken stall in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, with tight rules on who he serves, when, and how.

Li has suddenly become one of the most trending people on Chinese social media under the nickname “Chicken Chop Brother” (鸡排哥 jīpáigē).

Li initially gained popularity among customers for his frantic, multitasking energy — he doesn’t mess around when it comes to his chicken chop business, with superspeed and a clear order of serving customers (“I’ll first do you, then finish yours, then I’ll serve you 做完你的做你的”) and rules such as: no individual customers after 4:30 PM; students pay 1 yuan (about $0.15) less than regular passersby (after 12:00 PM, however, it costs 1 yuan more as punishment for being indecisive); and customers must open the plastic bag themselves before he puts the hot chicken cutlet inside.

The serious way he goes about dealing with his chicken chops almost makes you think he was making big business deals instead of selling to middle school students. In the end, it’s that attitude that gained him social media fame, as students started referring to him as “Head of Chicken Cutlet Operations” (free translation for 鸡排主理人 Jīpái gē Zhǔlǐrén).

Head of Chicken Chop Operations: “Please open your plastic bag”, “No individual customers after 4:30 PM”, etc.

In light of Li’s explosive popularity, his chicken chop stall now sees extremely long queues, and local authorities and city management have had to intervene in order to control the crowds and keep the location safe.

There are definite downsides to such sudden fame, and Li is not the first street vendor this has happened to.

In 2023, for example, Beijing’s ‘Auntie Goose Legs’ (鹅腿阿姨) went viral, and the food stall owner became so overwhelmed that she temporarily had to take a break from her food stall, emotionally sharing how she said she felt too much pressure because of how the situation was unfolding, and that she just wanted to sell her goose legs in peace (“只想平平安安做烧烤”).

Long lines for Auntie’s goose legs.

It seems that “Brother Chicken Chops”, in line with his reputation as the chicken chop CEO, is trying to turn his viral moment into a sustainable business. According to Sina News, Li has drawn in relatives to help him. He reportedly has taught them how to make and sell his tasty fried chicken chops, and now his Chicken Chop Family (“鸡排家族”) has grown to a total of nine stalls.

Over the past week, Li has also joined several social media platforms, including Xiaohongshu, to build a social following that will last after the hype calms down.

Meanwhile, Li is the meme of the moment. As many Chinese workers experience working stress before the National Day holiday, they’ve used his superspeed working style videos to express the pressure they feel to finish all their deadlines. See videos here.

— What Else Is Trending —

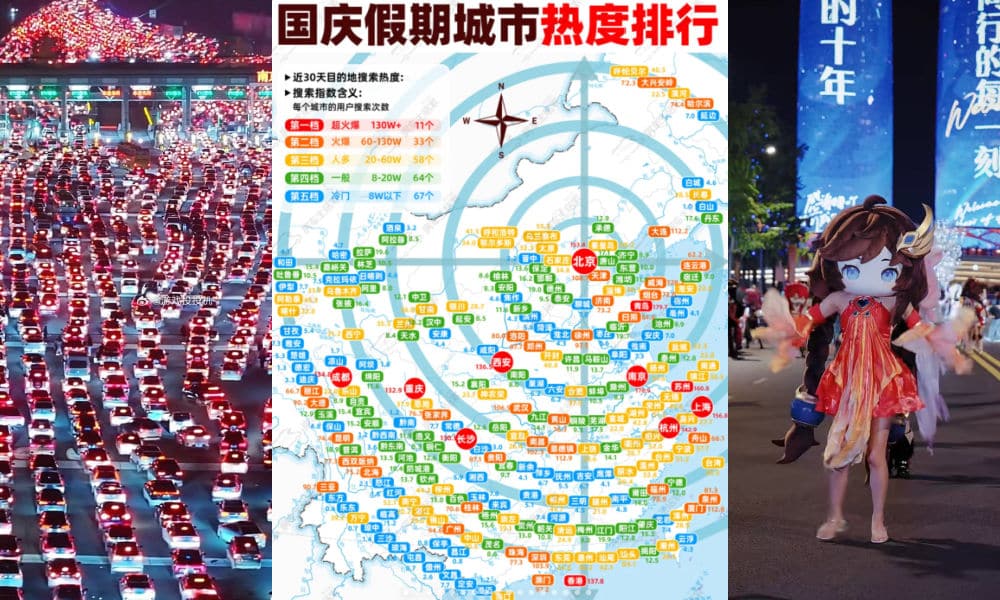

2. China’s 2025 Golden Week Travel Trends

China’s longest holiday of 2025 is coming up, combining National Day (国庆节) and Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节) into an eight-day Golden Week from October 1–8. If you’re traveling in China this week, good luck — the country’s transportation infrastructure is being pushed to its operational limits.

On September 30, the first “smart people” who opted to leave early to avoid traffic jams already found themselves stuck in them. China’s Ministry of Transport estimates a staggering 2.36 billion trips will be made during this period, with October 1 expected to see over 340 million travelers — surpassing the historical peak of 339 million recorded during Spring Festival earlier this year.

🔸 This week is going to see a lot of events. According to the Ministry of Culture & Tourism, more than 12,000 cultural activities will be held across China during the eight-day holiday period, including over 300 large-scale light shows.

🔸 Chinese local tourism offices are going all in on city marketing and are finding new strategies to make themselves more appealing to young travelers. Chengdu, for example, as Tencent’s gaming hub, is integrating the 10th anniversary of the super popular mobile game Honor of Kings (王者荣耀, Wángzhě Róngyào) into its cultural tourism strategy this year, organizing game-themed city walks, exhibitions, and more.

🔸 China’s travel platform Trip.com reported that interprovincial travel bookings have surged 45% year-on-year, with particularly strong interest in remote destinations like Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia. Searches for hotels in these regions jumped 60% compared to last year. This reflects a shift among middle-class Chinese tourists toward experiential travel and natural landscapes rather than crowded urban attractions.

🔸 The holidays are a time for relaxation, reunions, and eating mooncakes, but it’s also a stressful time for Chinese employers who must comply with labor regulations while managing workforce availability and overtime obligations. Under China’s Labor Law, employees working on statutory public holidays—October 1–3 and October 6 (the official Mid-Autumn Festival date)—must receive at least 300% of their normal daily wage. For adjusted rest days (October 4–5 and October 7–8), employers must provide either 200% overtime pay or compensatory time off. The State Council designated September 28 (Sunday) and October 11 (Saturday) as make-up workdays, but private companies have flexibility to adjust their own schedules.

3. China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

China is facing a serious donkey shortage. China’s donkey population is far below market demand, and the prices of donkey-related products continue to rise. The Donkey Branch of China’s Livestock Association (中国畜牧业协会驴业分会) addressed this issue in Chinese media earlier last week, telling China News Weekly (中国新闻周刊): “We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

4. “Ride-hailing for Relatives” 亲属打车 Qīnshǔ Dǎchē

Tencent has rolled out a new function via WeChat Mini Programs on September 26, aimed at helping seniors who struggle with app-based ride-hailing. Thanks to the new function, now live nationwide, users can order rides on behalf of older relatives directly in WeChat.

Adult children who want to help out their less tech-savvy (grand)parents or other senior relatives can now bind their account to their own, remotely pre-set pickup and drop-off locations, as well as payment methods, and track their journey for safety.

What makes this different from the possibility of just ordering a ride for someone else is that the seniors stay in control to some extent and can see their own journeys on their own phones. Children can configure settings on their side, while the interface for the elderly users is simplified. This allows seniors to ride independently, with a little help from their family.

The move is part of a broader effort in China to make it easier for seniors to stay involved in the digitalization of society.

The word to know is 亲属打车 qīnshǔ dǎchē, consisting of “亲属” qīnshǔ (relatives) and ride-hailing 打车 dǎchē.

5. What’s Trending at a Glance

- ✈️ The 27-year-old Sichuan creator “Tang Feiji” (唐飞机) died in a plane crash while livestreaming on Sept 27. The ultralight aircraft, piloted and purchased by Tang himself, went out of control and crashed before catching fire. Over 1,000 viewers were watching live, with the chat flooded by messages pleading for someone to rescue him. Local village officials confirmed his death. The tragedy is fueling debate over amateur aviation and extreme content creation.

- 🟢 Weibo has rolled out a visible “online status” feature on personal pages, showing when users are online, and not everyone is happy with it. The new feature is met with criticism from concerned users who don’t want others to see they’re online. It brings back memories of China’s legendary IM app QQ, which, like MSN, showed the online status of users.

- 🥿 A Chinese Marriott hotel location in Changzhou has come under scrutiny adn triggered hygiene concerns after guests found out that the in-room hotel slippers were being reused. The hotel has admitted to disinfected the disposable slippers and reusing them 2–3 times, without disclosing this to guests in advance.

- ⚖️ China’s cyberspace authorities issued stern warnings and announced penalties on various Chinese social platforms recently, including Xiaohongshu, Weibo, and Kuaishou, which are blamed for not keeping celebrity gossip and low-quality content in check and for influencing their hot search rankings. This is all about algorithm governance and the tightrope platforms walk in serving readers, attracting attention, and satisfying regulators.

- 👵 “Outsourced Children” services for Chinese seniors went trending recently. In Dalian, an initiative offering companionship and mediation services for seniors charges 500–2,500 yuan ($70–$350) per visit and has apparently been quite a success, underscoring strong market demand of eldercare-related services and new opportunities for Chinese students.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral5 months ago

China Memes & Viral5 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained