China Youth & Education

Chinese Arts Students into Panic Mode after Failing to Register for Exams Amid Announced Reforms

“The collapse of one app is affecting our entire future.”

Published

7 years agoon

Thousands of Chinese arts students have been unable to register for their upcoming exams this week, leading to great anger on social media. Now that China’s examination system is undergoing changes that will affect students majoring in arts, many fear that this was their last chance of ensuring a place at the higher education system they were aiming for.

This week, thousands of Chinese art undergraduates have gone into full panic mode for not being able to register for their upcoming exams.

The college enrollment procedures for students planning to major in ‘arts’ (covering fields of music, painting, dancing, design, film & TV, etc.) is different from students within other fields; those majoring in arts have to complete a college-level exam along with a provincial-level exam before taking the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE), commonly known as Gaokao.

On January 6th, allegedly around 700,000 students who tried to register for their college-level exam through the Yishisheng (艺术升) registration app found the system unresponsive, making the issue a trending topic on Chinese social media.

The hashtag “700,000 Arts Exam Candidates Lose Registration Qualification” (#70万艺考生丧失报名资格#) received more than 150 million views on Weibo at time of writing, with many students being angered and stressed, saying that “the collapse of one app is affecting our entire future.” At time of writing, it is not sure how the reports have come up with the 700,000 number, although it is probable that this is based on numbers of previous years, or based on the number of people taking the provincial-level exams (this link for reference).

What’s the Deal with Chinese Art Students?

The Gaokao (高考) or China’s National Higher Education Entrance Examination is well-known for being notoriously tough and super competitive. Every summer, millions of Chinese undergraduates take the exams for two days in a row or longer, depending on the major they are applying for and the provinces they are registered in. The result of this annual exam is set as the common entry criterion reference for university admission.

For students specializing in arts, their journey to the Gaokao examinations already starts earlier in the year. Arts students take the college-level supplementary exam (known as xiaokao 校考 or jiashi 加试), for which they have to register separately. All art students are also required to participate in the provincial exams (liankao 联考 or tongkao 统考), where their understanding of basic art knowledge and relevant art skills will be tested.

Only students who have passed these provincial exams will receive the certification that is needed in order to take the exams in June.

Image via http://news.southcn.com.

The extra challenge also provides extra opportunities for art students. Different from other students, art students’ final score is based on multiple grades, namely that of the aforementioned (1) supplementary university exam (校考), (2) the combined arts exam (联考), and (3) the gaokao (高考). Every art student is required to pass the combined arts exam, but have the benefit that most universities set relatively lower requirements for their gaokao scores once they have passed.

Once these art students are admitted to universities, their department choices, however, are not limited to arts per se. Arts students are thus sometimes labeled as being ‘opportunists,’ who allegedly take an ‘easy route’ to enter top-level universities.

The “Art exam” is not the “Easy Exam” (imagevia Sohu.com)

But the idea that the arts route is the easy route is often debunked in Chinese media and on social media, where it is argued that arts students have to work harder to invest in their field of specialty, and therefore are doing anything but taking the ‘easier’ road into their higher education career.

Announced Reforms in the Exam System

The controversial ‘shortcut,’ however, may disappear in the nearby future. On December 29, 2018, the Ministry of Education issued an article on art exams, suggesting that the general knowledge gaokao score will become more important and decisive in the future.

After the proposed reform, there will allegedly be a limit on the supplementary arts exams at educational institutions, meaning that art students with a lower gaokao score will no longer be admitted.

On the discussion boards of Chinese Q&A site Zhihu, various pages are discussing the upcoming reforms. Some commenters wrote that they support changes to the system, believing it will filter out ‘the opportunists’ from art education and keep the ‘real art lovers’ in.

Others voice different opinions, arguing that the reform is unfair to talented arts students and that it will lead to art schools being dominated by ‘bookworms.’ One current arts student (named @乔贰乔) questions the importance for art students to have a high general knowledge course score, and quotes a Chinese proverb, saying: “People master different fields” (术业有专攻).

If the reform is implemented, 2019 will be the last year for arts students to enjoy the lower gaokao score advantage. Previously, undergraduates who were not satisfied with their gaokao scores could go back to high school and try again the next year. The reform, however, would ban comprehensive universities from holding individual arts exams after 2019, making this year’s exams a pivotal one for many arts undergraduates who hope to get into their dream university.

Registration Chaos at ‘Yishusheng’ App

Besides the extra stress caused by the reform, this year’s arts students find themselves facing an unexpected difficulty: not being able to register for their college-level exams (xiaokao 校考).

The exam registration app Yishusheng (艺术升), the only authorized arts exam registration system for the top arts educational institutions, was not capable of handling the large data flow this week and broke down shortly after opening the registration.

The app is also being accused of promoting its 598 yuan (90 USD) VIP membership, with which the registration process would allegedly be accelerated.

By now, thousands of art students have shared their disappointment and anger over not being able to register at such a crucial moment. Some netizens commented that they have tried to register for the Art Academy of Xi’an’s entrance exam for over three hours, but never succeeded. Others say they have been up all night together with their parents, desperately trying to get a spot for their examinations.

The failing app.

Sina News also reported that some students succeeded in registering in Jiangsu province, but then later discovered their examination would allegedly take place in Lanzhou, Gansu province, according to the app.

On January 7, Beijing News reported that, according to the Yishusheng app, part of the problem is that there is a decrease in art institutions across the nation and that examination sites have been reduced, suggesting that simply “too many people” were registering for the exams.

On its official Weibo account, the Yishusheng app briefly apologized for the recent crisis, and thoroughly explained the efforts the app has put into making their system better. They also state that the system is “back to normal,” while in the various comments sections, people still complain that they cannot enter the registration page.

For now, it does not seem that the storm has blown over yet, especially because Weibo netizens are also angered about the fact that this topic, although receiving so many views, did not appear in the ‘hot search’ or ‘top trending’ lists, with many people suspecting the issue is purposely being kept under the radar.

“I am just so disappointed, so incredibly disappointed,” one disgruntled commenter writes.

By Boyu Xiao, with contributions by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Boyu Xiao is an MPhil graduate in Asian Studies (Leiden University/Peking University) focused on modern China. She has a strong interest in feminist issues and specializes in the construction of memory in contemporary China.

You may like

China Insight

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

“You think we’re scared of you? It’s not like we haven’t been to jail before.”

Published

1 month agoon

August 6, 2025

These days have been filled with tension and anger in the city of Jiangyou (江油市), Sichuan, after a rare, large-scale protest broke out following public outrage over a severe bullying incident and how it was handled.

The bullying incident at the center of this story happened outside school premises in Mianyang on the afternoon of July 22. Footage of the assault, recorded by bystanders at the scene, began circulating widely online on August 2, sparking widespread outrage among concerned netizens, many of them worried parents.

The violent altercation involved three girls between the ages of 13 and 15 who ganged up on another minor, a 14-year-old girl named Lai (赖).

After Lai and a 15-year-old girl named Liu (刘) reportedly had a dispute, Liu gathered two of her friends—the 13-year-old also named Liu (刘) and a 14-year-old named Peng (彭)—to gang up on Lai.

The three underage girls lured Lai to an abandoned building, where they subjected her to hours of verbal and physical violence. The footage showed how they took turns in kicking, slapping, and pushing her.

At one point, after Lai said she would call the police, one of the bullies yelled: “You think we’re scared of you? It’s not like we haven’t been to jail before. I’ve been in more than ten times—it doesn’t even take 20 minutes to get out” (“你以为我们会怕你吗?又不是没进去过,我都进去十多次了,没二十分钟就出来了”).

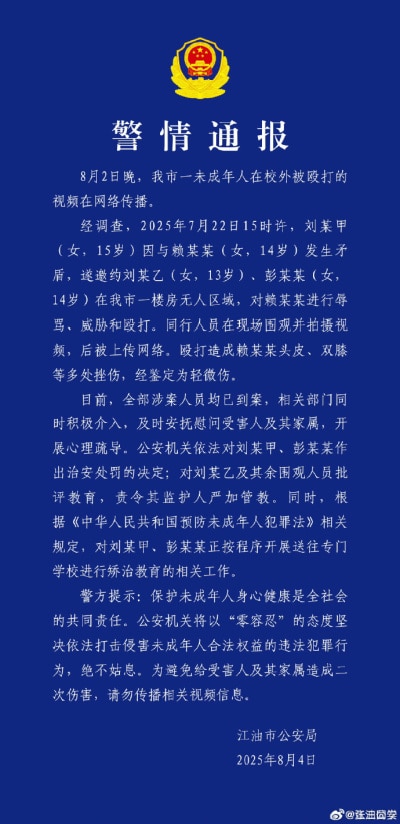

That same night, the incident was reported to police. It took authorities until August 2 to bring in all involved parties for questioning, and a police report was issued on the morning of Monday, August 4.

Police report by Jiangyou Public Security Bureau, confirming the details of the incident and the (legal) consequences for the attackers.

Two of the girls (the 15- and 14-year-old) were given administrative penalties and will be sent to a specialized correctional school. The younger Liu and other bystanders were formally reprimanded.

“Parents Speak Out for the Bullied Girl”

The way the incident was handled—not just the relatively late official report, but mostly the perceived lenient punishment—triggered anger online.

Many people who had seen the video responded emotionally and felt that the underage girls should be stripped of their rights to take their exams, and that the bullying incident should forever haunt them in the same way it will undoubtedly haunt their victim.

Especially the phrase “It’s not like I haven’t been taken in [to jail] before” struck a chord, as it showed just how calculated the bullies were—and how, by counting on the leniency of the Chinese judicial system for minors, they made the system complicit in their determination to turn those hours into a living hell for Lai.

China has been dealing with an epidemic of school violence for years. In 2016, Chinese netizens were already urging authorities to address the problem of extreme bullying in schools, partly because minors under the age of 16 rarely face criminal punishment for their actions.

Since 2021, children between the ages of 12 and 14 can be held criminally responsible for extreme and cruel cases resulting in death or disability—but their legal prosecution must first be approved by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP).

It has not done much to stop the violence.

Discussions around extreme bullying like this have repeatedly flared up over the years, such as in 2020, when a 15-year-old schoolboy named Yuan (袁) in Shaanxi was fatally beaten and buried by a group of minors.

Last year, a young boy named Wang Ziyao (王子耀) was killed by three classmates after suffering years of bullying. His body was found in a greenhouse just 100 meters from the home of one of the suspects, and the case shocked and enraged local residents.

But the problem is widespread among girls, too.

In 2016, we already reported on how so-called ‘campus violence videos’ (校园暴力视频) had become a concerning trend. In these kinds of videos—often showing multiple bullies beating up a single victim on camera—it’s not uncommon to see girls as the aggressors.

Girls often form cliques to gang up on a victim to show that they are in control or to gain popularity. They also tend to be more inclined than boys to make cruel jokes or stage pranks meant to embarrass or humiliate their target. This may partly explain why there seem to be more campus violence videos on Chinese social media showing girls bullying girls than boys bullying boys.

In the case of Lai, she appears to have been particularly vulnerable. One of her relatives posted online that her mother is deaf and mute, and her father allegedly is disabled. This fact may have contributed to why Lai was repeatedly targeted and bullied by the same group of girls, who reportedly took away her phone and socially isolated her at school.

In response to the incident, netizens started posting the hashtag “Parents Speak Up for the Bullied Girl” (“#家长们为被霸凌女孩发声#), not only to support Lai and her family, but to demand harsher punishments for school bullies and for stricter crackdown on this nationwide problem.

From Online Anger to Offline Protest

While many people spoke out for Lai online, hundreds also wanted to show up for her in person.

On August 4, dozens of people gathered in front of the Jiangyou Municipal Government building (江油市人民政府) to demand justice and support Lai’s parents, who had come to express their grievances to the authorities—at one point even bowing to the ground in a plea for justice to be served for their daughter.

Footage and images circulating on social media showing the parents of Lai, the victim, bowing on the ground to demand justice from authorities.

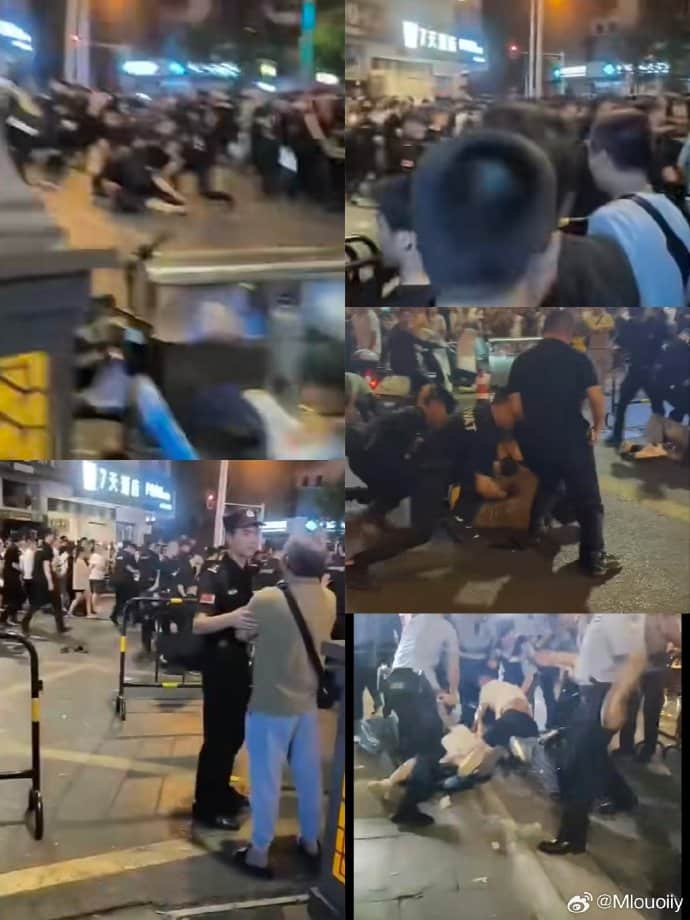

As the crowd grew larger, tensions escalated, eventually leading to clashes between protesters and police.

The arrests at the scene did little to ease the situation. As night fell, the mood grew increasingly grim, and some protesters began throwing objects at the police.

Images of the protest, posted on Weibo.

Near the east section of Shixian Road (诗仙路东段), more people gathered. Hundreds of individuals filming and livestreaming captured footage of the police crackdown—officers beating protesters, dragging them away, and deploying pepper spray.

Netizens’ digital artwork about the bullying incident, the parents’ grievances, and the public protest and its crackdown in Jiangyou. Shared by 程Clarence.

Although the protests briefly gained traction on social media and became a trending topic on Weibo, the search term was soon removed from the platform’s trending list.

Lasting Mental Scars

On Tuesday, August 5, several topics related to the Jiangyou bullying incident began trending again on Chinese social media.

On the short video app Kuaishou, a collective demand for justice surged to the number one spot, under the tag “A large number of Jiangyou parents demand justice for the victim” (江油大批家长为受害学生讨公道).

As of now, none of the perpetrators’ families have come forward to apologize.

As for Lai—according to the latest reports, she did not suffer serious physical injuries from the bullying incident, but according to her own parents, the mental scars will last. She will need continued mental health support and counseling going forward.

Although many posts about the incident and the ensuing protests have been taken offline, ‘Jiangyou’s Bullying Incident’ has already become one more case in the growing list of brutal school bullying incidents that have surfaced on Chinese social media in recent years. The heat of local anger may fade over time, but the rising number of such cases continues to fuel public frustration nationwide—especially if local authorities fail to do more to address and prevent school bullying.

“Not being able to protect our children, that’s a disgrace to our schools and the police,” one commenter wrote: “I want to thank all those mothers who have raised their voices for the bullied child. Each of us must say no to bullies, and we must do all we can to stop them. I hope the lawmakers agree.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Local News

Six Chinese Students Dead After Falling Into Flotation Tank During Mine Visit

After six students drowned in a mine tank, social media users question safety precautions and media framing.

Published

1 month agoon

July 25, 2025

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China this week. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

The tragic death of six Chinese students during a visit to the Wunugetushan Copper-Molybdenum Mine (乌努格吐山铜钼矿) in Inner Mongolia has been trending on Chinese social media this week.

The students, who study mineral processing engineering at the School of Resources & Civil Engineering Northeastern University (东北大学), visited the site as part of their studies on Wednesday, July 23.

The facility, which operates under the state-owned China National Gold Group Corporation (中国黄金集团), includes a mineral processing plant where ore is crushed and processed using flotation cells to separate copper and molybdenum concentrate from waste rock.

The students were standing on a metal grate above a deep industrial tank used for mineral processing. The grate then suddenly collapsed, and they fell into the flotation tank, which was filled with mineral slurry (see this video to better understand the situation).

The tank was deep, and once inside, the slurry made it impossible to swim.

By the time the students were taken out of the tank, they had already drowned. They were all aged between 20 and 22. One of their teachers was injured in the incident.

According to Sohu News, citing a preliminary accident investigation report, the direct cause of the incident was a pre-existing crack in the grate above the tank, which caused the entire panel to flip and fall off. The grates had been replaced in February but were not properly tested. The site also lacked warning signs about load capacity and reportedly did not restrict the number of people allowed to stand on it.

Three people responsible for safety measures at the site, including the deputy general manager, have now been placed under criminal detention.

Besides the many questions surfacing online about how such a gruesome accident could have occurred, there is also criticism of how the media has reported on the incident. Some outlets mentioned that the 45 other intern students—presumably also present during the visit—were “emotionally stable,” and that the teacher who was injured was in a “good mental state.”

One blogger criticized these phrases, which are often used in media reports following similar incidents. While they appear to describe the psychological condition of survivors or bystanders, the author argued that they are more political than psychological: their real function is to signal to readers that—despite the loss of life—the situation remains under control.

After the online criticism, the Weibo hashtag “45 Intern Students from Northeastern University Are Emotionally Stable” (#东北大学45名实习学生情绪平稳#) has since been taken offline.

At the time of writing, the official website of Northeastern University has been changed to black and white.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

The Final Countdown: China’s Military Parade on Social Media

How Female Comedians Are Shaping China’s Stand-Up Boom

China Trend Watch Top 10: Putin & Kim Jong-un in Beijing, Meituan’s Upcoming Changes, Lu Xun’s Mural Controversy

China Trend Watch: Naked Sleeping Woman Claims Depression After Being Seen by Window Cleaners

Online Debates About China’s Train Traditions: No More Instant Noodles or Cigarette Breaks?

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral2 months ago

China Memes & Viral2 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature10 months ago

China Books & Literature10 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Society11 months ago

China Society11 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China Insight4 months ago

China Insight4 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal