China Youth & Education

Chinese Arts Students into Panic Mode after Failing to Register for Exams Amid Announced Reforms

“The collapse of one app is affecting our entire future.”

Published

6 years agoon

Thousands of Chinese arts students have been unable to register for their upcoming exams this week, leading to great anger on social media. Now that China’s examination system is undergoing changes that will affect students majoring in arts, many fear that this was their last chance of ensuring a place at the higher education system they were aiming for.

This week, thousands of Chinese art undergraduates have gone into full panic mode for not being able to register for their upcoming exams.

The college enrollment procedures for students planning to major in ‘arts’ (covering fields of music, painting, dancing, design, film & TV, etc.) is different from students within other fields; those majoring in arts have to complete a college-level exam along with a provincial-level exam before taking the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE), commonly known as Gaokao.

On January 6th, allegedly around 700,000 students who tried to register for their college-level exam through the Yishisheng (艺术升) registration app found the system unresponsive, making the issue a trending topic on Chinese social media.

The hashtag “700,000 Arts Exam Candidates Lose Registration Qualification” (#70万艺考生丧失报名资格#) received more than 150 million views on Weibo at time of writing, with many students being angered and stressed, saying that “the collapse of one app is affecting our entire future.” At time of writing, it is not sure how the reports have come up with the 700,000 number, although it is probable that this is based on numbers of previous years, or based on the number of people taking the provincial-level exams (this link for reference).

What’s the Deal with Chinese Art Students?

The Gaokao (高考) or China’s National Higher Education Entrance Examination is well-known for being notoriously tough and super competitive. Every summer, millions of Chinese undergraduates take the exams for two days in a row or longer, depending on the major they are applying for and the provinces they are registered in. The result of this annual exam is set as the common entry criterion reference for university admission.

For students specializing in arts, their journey to the Gaokao examinations already starts earlier in the year. Arts students take the college-level supplementary exam (known as xiaokao 校考 or jiashi 加试), for which they have to register separately. All art students are also required to participate in the provincial exams (liankao 联考 or tongkao 统考), where their understanding of basic art knowledge and relevant art skills will be tested.

Only students who have passed these provincial exams will receive the certification that is needed in order to take the exams in June.

Image via http://news.southcn.com.

The extra challenge also provides extra opportunities for art students. Different from other students, art students’ final score is based on multiple grades, namely that of the aforementioned (1) supplementary university exam (校考), (2) the combined arts exam (联考), and (3) the gaokao (高考). Every art student is required to pass the combined arts exam, but have the benefit that most universities set relatively lower requirements for their gaokao scores once they have passed.

Once these art students are admitted to universities, their department choices, however, are not limited to arts per se. Arts students are thus sometimes labeled as being ‘opportunists,’ who allegedly take an ‘easy route’ to enter top-level universities.

The “Art exam” is not the “Easy Exam” (imagevia Sohu.com)

But the idea that the arts route is the easy route is often debunked in Chinese media and on social media, where it is argued that arts students have to work harder to invest in their field of specialty, and therefore are doing anything but taking the ‘easier’ road into their higher education career.

Announced Reforms in the Exam System

The controversial ‘shortcut,’ however, may disappear in the nearby future. On December 29, 2018, the Ministry of Education issued an article on art exams, suggesting that the general knowledge gaokao score will become more important and decisive in the future.

After the proposed reform, there will allegedly be a limit on the supplementary arts exams at educational institutions, meaning that art students with a lower gaokao score will no longer be admitted.

On the discussion boards of Chinese Q&A site Zhihu, various pages are discussing the upcoming reforms. Some commenters wrote that they support changes to the system, believing it will filter out ‘the opportunists’ from art education and keep the ‘real art lovers’ in.

Others voice different opinions, arguing that the reform is unfair to talented arts students and that it will lead to art schools being dominated by ‘bookworms.’ One current arts student (named @乔贰乔) questions the importance for art students to have a high general knowledge course score, and quotes a Chinese proverb, saying: “People master different fields” (术业有专攻).

If the reform is implemented, 2019 will be the last year for arts students to enjoy the lower gaokao score advantage. Previously, undergraduates who were not satisfied with their gaokao scores could go back to high school and try again the next year. The reform, however, would ban comprehensive universities from holding individual arts exams after 2019, making this year’s exams a pivotal one for many arts undergraduates who hope to get into their dream university.

Registration Chaos at ‘Yishusheng’ App

Besides the extra stress caused by the reform, this year’s arts students find themselves facing an unexpected difficulty: not being able to register for their college-level exams (xiaokao 校考).

The exam registration app Yishusheng (艺术升), the only authorized arts exam registration system for the top arts educational institutions, was not capable of handling the large data flow this week and broke down shortly after opening the registration.

The app is also being accused of promoting its 598 yuan (90 USD) VIP membership, with which the registration process would allegedly be accelerated.

By now, thousands of art students have shared their disappointment and anger over not being able to register at such a crucial moment. Some netizens commented that they have tried to register for the Art Academy of Xi’an’s entrance exam for over three hours, but never succeeded. Others say they have been up all night together with their parents, desperately trying to get a spot for their examinations.

The failing app.

Sina News also reported that some students succeeded in registering in Jiangsu province, but then later discovered their examination would allegedly take place in Lanzhou, Gansu province, according to the app.

On January 7, Beijing News reported that, according to the Yishusheng app, part of the problem is that there is a decrease in art institutions across the nation and that examination sites have been reduced, suggesting that simply “too many people” were registering for the exams.

On its official Weibo account, the Yishusheng app briefly apologized for the recent crisis, and thoroughly explained the efforts the app has put into making their system better. They also state that the system is “back to normal,” while in the various comments sections, people still complain that they cannot enter the registration page.

For now, it does not seem that the storm has blown over yet, especially because Weibo netizens are also angered about the fact that this topic, although receiving so many views, did not appear in the ‘hot search’ or ‘top trending’ lists, with many people suspecting the issue is purposely being kept under the radar.

“I am just so disappointed, so incredibly disappointed,” one disgruntled commenter writes.

By Boyu Xiao, with contributions by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Boyu Xiao is an MPhil graduate in Asian Studies (Leiden University/Peking University) focused on modern China. She has a strong interest in feminist issues and specializes in the construction of memory in contemporary China.

Also Read

China Society

Hero or Zero? China’s Controversial Math Genius Jiang Ping

Humble prodigy or deceptive impostor? Jiang Ping has been fueling online discussions since her remarkable score in the Alibaba maths competition.

Published

3 weeks agoon

July 5, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

It’s rare for a math competition to become the focus of nationwide attention in China. But since 17-year-old vocational school student Jiang Ping made it to the top 12 among contestants from prestigious universities worldwide, her humble background and outstanding achievement sparked debates and triggered rumors.

About a month ago, nobody had ever heard of Jiang Ping (姜萍). But that all changed in June 2024, when the Alibaba Global Mathematics Competition announced its finalists. Organized by Alibaba’s DAMO Academy in collaboration with the China Association for Science and Technology and the Alibaba Foundation, this competition is open to math enthusiasts worldwide.

This year, among the finalists from top universities around the globe, the 17-year-old Jiang Ping from Jiangsu province stood out. Scoring 93 points and ranking 12th globally, she was not just the only girl in the top 30 but she was also not even a math major—Jiang studies fashion design at a local vocational school. Her remarkable score, combined with her humble background, thrust her into the center of an unexpected public debate.

‘Good Will Hunting’

When the Alibaba Math Competition finalist list was announced in June, Jiang Ping became an instant internet sensation. Her story seemed straight out of an inspiring movie: a poor family, a modest educational background, and exceptional intelligence.

According to her parents and teachers, Jiang Ping had excelled at math since middle school, far surpassing her peers. However, her talent was limited to mathematics, and her weakness in other subjects meant she could only attend a vocational school, and she enrolled at Lianshui Secondary Vocational School, a path often seen as a dead end in China’s competitive educational landscape.

Fate intervened when her math teacher, Wang Runqiu (王闰秋), a master’s graduate from Jiangsu University who never qualified for a PhD program, noticed her extraordinary talent during a monthly math exam. Wang, who also participated in Alibaba’s competition and ranked over 100th, provided Jiang with advanced math textbooks. He believed her potential should not go to waste.

Determined, Jiang Ping self-studied mathematics alongside her fashion design curriculum, even using an English-Chinese dictionary to understand partial differential equations textbooks in English. When Jiang heard that Alibaba’s competition had no educational requirements, she seized the opportunity, and her talent finally came to light.

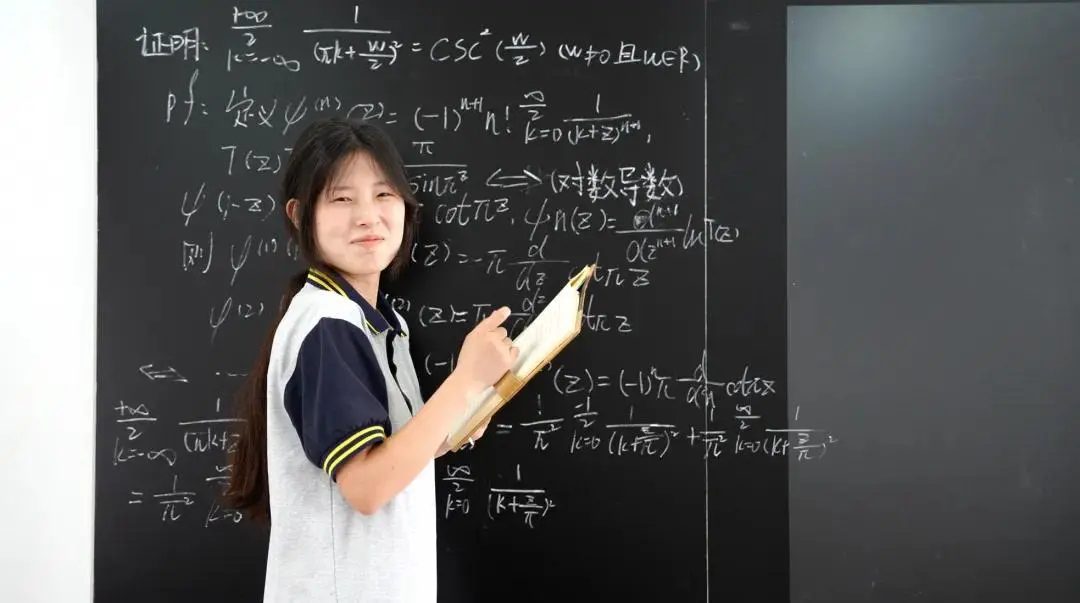

Jiang Ping, image via iFeng News.

The public initially seemed to love the story of a small-town Chinese girl experiencing a miraculous turning point in her life. Her 70-year-old father could hardly earn more than a few hundred yuan a month, and she often worked during holidays to help support her family.

According to Xinjing News, by March 2024, her family had applied for a subsistence allowance but had yet to receive it. After Jiang Ping’s story went viral, the allowance was immediately secured. Her village and school became new hotspots for influencers. Vloggers flocked to her home to film TikTok videos, and even tourists from other provinces visited Lianshui County just to take photos at Jiang’s school.

Wang Runqiu, Jiang Ping’s teacher

Everything seemed to be going well. Education blogger Luo Miao (@罗淼_吐槽用) posted that Jiang Ping and her teacher Wang Runqiu had achieved something more miraculous than the story portrayed in the American movie “Good Will Hunting,” which is also about a self-taught mathematical genius. However, the real world is not a movie. This celebration took a downturn in less than five days.

A Questionable Math Problem

Shortly after the finalists were announced and Jiang Ping’s name spread across social media, online discussions questioning her mathematical abilities began to emerge on forums like Zhihu. The focal point of these discussions was a scene from an official Alibaba video where Jiang Ping is seen holding scratch paper and solving a math problem on a blackboard.

On June 18, a WeChat post by renowned math competition coach Zhao Bin (赵斌) was trending on Weibo. Zhao, who had participated in the Alibaba competition three times and made it to the finals each time, asserted that Jiang Ping’s advancement to the finals was 99.99% likely fabricated. He raised doubts about Jiang Ping’s solution process on the blackboard, pointing out issues like “the domain of definition was incorrect” and “the differentiation symbol is written in the wrong place.” He concluded that Jiang was not familiar with these math questions and may have simply copied the answers from her scratch paper.

Zhao Bin further suggested that this might be orchestrated by Jiang Ping’s teacher Wang Runqiu, who probably wanted to hype up Jiang Ping’s image as an unrecognized genius and his own image as a mentor. Zhao also stated that if he was wrong, Jiang Ping truly was a math prodigy and that if she would make it to university, he would personally finance her tuition fees.

On June 19, 39 contestants from the Alibaba competition released a petition to the organizing committee. Besides the problems addressed by Zhao, they mentioned another point of contention: a teacher who had seen Jiang Ping’s exam paper commented that she exhibited “proficient use of LaTeX” while answering questions. LaTeX, a typesetting system for scientific documents, is highly sensitive to writing errors, which contradicts the frequent errors in Jiang Ping’s handwriting in the video.

This was also mentioned by Peking University professor Yuan Xinyi (袁新意) in a lengthy analysis on Zhihu, where he argued that as a vocational school student, Jiang Ping couldn’t possibly be proficient in using LaTeX. In their petition, the 39 contestants put forth specific demands, including the public release of Jiang Ping’s answer sheets for review by all finalists and a request for an independent third-party investigation.

Of course, there are those who choose to believe in Jiang Ping. Science fiction writer Bei Xing (@北星微博) made meticulous notes and explanations of Jiang Ping’s problem-solving process on the blackboard. He concluded that it was impossible to have such a clear approach if she had just copied someone else’s answers, as Zhao assumed. It was also understandable for a 17-year-old who had almost entirely self-taught herself to make some writing errors and formatting irregularities.

Up until this point, most discussions were still about academic integrity. But the fact that Alibaba and Damo Academy did not directly address these doubts only triggered more rumors. Many influencers with large followings, despite lacking a math background, also started to chime in with comments like “Jiang Ping doesn’t even recognize mathematical symbols,” leading to another surge of speculation and defamation directed at Jiang Ping.

Online Chaos

On June 23rd, the Weibo user ‘Oxford Kate Zhu Zhu’ (@牛津Kate朱朱), a mathematics PhD candidate at Oxford University, posted on Weibo that she had faced significant online abuse after expressing support for Jiang Ping. She said that she has sought legal assistance to deal with the online attacks. This post, which quickly went viral, showed how the controversy surrounding Jiang Ping has gone beyond mathematics or academic integrity.

By June 20th, Jiang Ping herself had already been doxxed. Someone posted her personal information online, including photos of her ID card. This practice is referred to as “opening the box” (开盒) on the Chinese internet. Netizens on platforms like Zhihu and Hupu began spreading rumors about Jiang Ping and her relationship with her mathematics teacher, with so-called “informants” even coming forward to allegedly confirm their “improper relationship.” Subsequently, a screenshot of Jiang Ping’s previous math exam score, showing she had scored only 83 points, was also leaked.

Professor of Criminal Law at Tsinghua University Lao Dongyan (@劳东燕2004) expressed concern about this situation, posting on Weibo to remind netizens that while people have the right to question Jiang Ping’s remarkable results, they should not throw around baseless accusations and push the debate in a direction that borders on defamation.

However, many people continue to see Jiang Ping’s amicable relationship with her teacher and her former 83-point exam score as justification to spread her private photos, transcripts, and even monthly exam papers on the Internet.

By now, the situation has become so messy that the Education Bureau of Lianshui County had to step in and set the record sraight on some trivial matters, such as the authenticity of Jiang’s monthly exam score and whether some teacher had bought her snacks or not.

Wang Hongqin vs Jiang Ping

Amidst the chaos, voices of reason remain: some netizens have expressed disappointment at Alibaba’s continued silence. They suggest that regardless of how Jiang Ping made it to the math competition finals, as an underage girl, she should not be thrust into the eye of the hurricane.

Meanwhile, another story has drawn parallels to Jiang’s situation. Recently, some netizens discovered that the son of the famous Chinese actress Wang Yan (王艳), Wang Hongqin (王泓钦), was admitted to Peking University as a “high-level athlete” based on his basketball talent. However, there are publicly available records indicating that his athletic achievements were not that impressive at all.

Wang Hongqin and Jiang Ping

This raised many discussions on Chinese social media. Netizens questioned why Jiang Ping, with her outstanding math achievements, wasn’t celebrated in the same way as Wang Hongqin. Others highlighted the disparity in opportunities for talented student from different backgrounds.

There were also questions about why Jiang Ping was receiving so much online hate, while Wang Hongqin did not. Under a Weibo post discussing Wang Yan’s son’s admission to Peking University, one comment explained public reasoning: “Wang Yan has access to high-level resources that are out of reach for ordinary people. In contrast, Jiang Ping is seen differently. When someone tries to break through societal layers [like that], they are dragged out and “paraded” through the streets.”

The discussions on the different public reactions to Wang Hongqin and Jiang Ping relate to a time of social insecurity when people face a competitive education system and a worsening job market. In this context, they are less likely to relate to “zero to hero” stories.

When someone with a low educational background achieves success, they are now often seen as cheaters rather than being celebrated. While people often feel powerless to challenge the privileges of the elite, the sudden rise of a vocational school student like Jiang Ping intensifies feelings of deprivation and being bypassed. Even though Jiang might have reached the finals through her own mathematical talent, there is still a lot of resentment towards the 17-year-old rural girl, who lacks background and connections. This misplaced anger is a reflection of deeper societal issues and inequalities.

Despite being at the center of the battlefield of public opinions, Jiang Ping has not made any statement yet. On June 22nd, she participated in Alibaba’s math competition finals, and perhaps now—as in every summer before—she is preparing to find a part-time job to support her family. The outcome of the finals will be announced in August, so Jiang Ping’s story will undoubtedly be continued.

By Ruixin Zhang

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

China’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

It’s Gaokao time! For the first time, China’s Gaokao essay topic was about the latest AI developments, triggering discussions on social media.

Published

2 months agoon

June 7, 2024

This week, China’s National College Entrance Exams, better known as the “Gaokao” (高考), became one of the most-discussed topics on Chinese social media. ‘Gaokao,’ ‘AI,’ and ‘Gaokao essay’ were the hottest words on Weibo by the end of the week.

The Gaokao (literally: ‘higher exams’) are a prerequisite for entering China’s higher education institutions and are usually taken by students in their last year of senior high school. June 7th marked the first day of the Gaokao, which will continue until June 9th.

For the over 13.4 million participating students, the Gaokao week is a pivotal moment. Scoring high on this exam can grant access to better colleges, significantly improving their chances of obtaining a good job after graduation. Given the potentially life-changing results, the Gaokao period is a stressful time for both students and their parents.

The Gaokao essay (高考作文) is a significant component of the Chinese language exam, testing students’ writing skills, critical thinking, and ability to express ideas coherently. The essay, which must be completed within a limited time, requires students to discuss given topics.

These topics are generally related to Chinese society and culture, consistently attracting attention on social media. This year, multiple essay questions were related to AI and social media.

Those taking the Beijing exam (北京卷), for example, received a question related to the “like” function on WeChat, suggesting that some people feel strongly about the number of “likes” they receive and give, asking students to reflect on the phenomenon of receiving and giving “likes” on social media.

But the question receiving the most attention on social media was part of the New Curriculum Standard Test I (新课标I卷), which is distributed among different provinces.

Students vs. Chatbots: Letting AI Write an Essay on AI

Students received the following topic prompt for their Gaokao essay, which should be at least 800 characters long:

“With the spread of the internet and AI applications, we can quickly get answers to more and more questions. Will this also lead to us having fewer problems?” (随着互联网的普及、人工智能的应用,越来越多的问题能很快得到答案。那么,我们的问题是否会越来越少?)

The question sparked discussions because it was the first time a Gaokao essay question focused on AI applications designed to interact with users, like ChatGPT.

Although many thought the essay question was easy—unlike this year’s math exam—it still generated some interesting reflections.

Some Weibo users responded that the answer to the question was within the question itself. One Weibo blogger answered: “If there were no AI, we wouldn’t have this question, so problems/questions related to AI will only increase. The emergence of new things will inevitably be accompanied by new problems.”

Others commented on the concerns brought by the emergence of AI applications like ChatGPT. In early 2023, hashtags such as “Ten Professions That Could be Replaced by ChatGPT” (#可能被ChatGPT取代的10大职业#) gained a lot of attention on Chinese social media, where many were concerned that jobs from various industries, including customer service, programming, media, education, market research, finance, etc., would soon be done by AI chatbots instead of humans.

In line with this thought and the AI theme of this year’s Gaokao essay, netizens and some Chinese media outlets decided to let various language models take the exam and see how they would perform: could AI actually do better in writing an essay about AI than Chinese students? (Related hashtags: #让AI写高考作文#, #假如AI写高考语文作文#; #ChatGPT来交卷了#).

Xinhua, for example, asked Open AI’s ChatGPT to answer various questions. Sina Tech (新浪科技) also asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT to answer the AI-related essay question, along with Chinese chatbots, like Baidu’s Erniebot (文心一言), Tencent’s Yuanbao (元宝), iFlytek’s Sparkdesk (星火), and Alibaba’s Tongyi Qianwen (通义千问). Toutiao News did the same, letting three chatbots (ChatGPT, Erniebot, Tongyi Qianwen) compete against each other.

There is no general consensus on how well these AI chatbots can write a Gaokao essay. Although compared to last year, there are now more and better domestic AI models, OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 is generally still seen as the best chatbot out there.

This was its answer (originally in Chinese, translated to English with ChatGPT):

New Issues and Thoughts Brought by Technological Progress

With the popularization of the internet and the application of artificial intelligence, we can quickly obtain a large amount of information, and many questions can be answered in a short time. However, does this mean that we will have fewer questions? I believe the answer is no.

Firstly, although technology provides us with convenience, new technologies also bring new problems. The popularization of the internet has made information dissemination faster, but at the same time, the authenticity and accuracy of information have become new concerns. Fake news, information overload, and privacy breaches are increasingly prominent issues. These new problems need to be identified, understood, and resolved by us.

Secondly, the application of artificial intelligence, although it improves efficiency, also brings ethical and social issues. The transparency of AI decision-making, algorithmic bias, and the impact on the job market are all urgent issues that society needs to address. People need to constantly raise new questions to ensure a balance between technological progress and social welfare.

Furthermore, the development of technology prompts us to reflect more deeply on humanity itself. We need to rethink the relationship between humans and technology and consider the role and boundaries of technology in our lives. These philosophical issues are more important than ever.

Therefore, technological progress does not reduce our questions but rather prompts more new questions and reflections. It is these constantly emerging questions that drive social progress and human thought. We need to embrace the challenges brought by technology with a more open and critical attitude and actively seek solutions.

Although the domestic chatbots gave somewhat different answers, the overall tone was similar, though some commenters argued that ChatGPT was still the strongest, along with iFlytek’s Sparkdesk.

An online poll asking Weibo users to grade the ChatGPT essay from lower than 20 points up to the full 60 points saw divided responses, though a majority rated it as lower than 20 points.

How well can ChatGPT write an essay about AI? Opinions are divided.

This shows that many commenters think that AI chatbots are still not able to beat humans when it comes to writing Gaokao essays.

Commenters reacted to the various AI-generated essays in various ways, including:

• “Actually, none of them are very good. They are too formulaic and standardized, lacking the natural creativity and originality that humans possess.”

• “They just give soulless standard answers.”

• “It’s all about ‘firstly,’ ‘secondly,’ ‘furthermore.'”

• “There are no examples, no points proven; it should be a low grade.”

• “It’s just too stiff.”

• “This is like reading reports, not essays.”

• “AI places more emphasis on logic, which aligns with the writing style of foreigners.”

• “There’s no feeling in these essays; there’s a certain kind of AI feeling to AI.”

Meanwhile, some bloggers are taking up the challenge and are publishing their own online essays in response to the Gaokao question.

Some of them are not worried that chatbots will take over their critical tasks: “AI will be AI. There’s no connection to the social realities, and it’s as cold as ice.”

“Their words might make sense, but they lack feeling.”

But for some discussing the topic, they have come to realize that they are already depending too much on digital tools and AI applications for their everyday tasks, writing: “I made an attempt to write an essay, but discovered I already forgot how to do it!” For them, the discussion itself is a wake-up call that writing an essay from scratch is a skill that requires practice and cannot be fully replaced by chatbots, making personal creativity essential to score points and avoid the ‘AI-fication’ of texts.

PS:

In his book China’s Millennials, Eric Fish describes the limits on Chinese students’ answers; taboo responses, such as those containing harsh criticisms of the Chinese government or society, could potentially lead to failure. Although the essay is purportedly meant to showcase the student’s creativity, it must adhere to the unwritten rules of what is socially acceptable.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?