China World

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking back at the Messi controversy: How a friendly match transformed into a political arena following Messi’s absence.

Published

2 years agoon

By

Ruixin Zhang

In the days leading up to the start of the Chinese New Year, the hottest topic on Chinese social media was not about the upcoming celebration – everyone was talking about soccer instead. Why? Because of the Inter Miami CF match in Hong Kong, featuring none other than the Argentine soccer superstar Lionel Messi.

After winning the World Cup in 2023, Messi left European soccer to join David Beckham’s American professional soccer club, Inter Miami CF. Starting in 2024, the team planned a series of preseason exhibition matches, including matches against Dallas FC, Al Hilal, Al-Nasr, Hong Kong, and Vissel Kobe.

On February 4th, the Hong Kong Stadium, filled with nearly 40,000 fans, finally hosted the legendary Lionel Messi. However, according to on-site reports, Messi, wearing casual pants and shoes instead of soccer cleats and shorts, spent the entire time on the bench.

Frustration among the audience grew, leading to an outbreak of boos due to Messi’s continuous absence. By the 80th minute, some fans started leaving, and chants of “refund” persisted, overshadowing the post-match speech of Inter Miami’s president David Beckham.

As the game concluded, additional videos and images from the scene spread online, fueling further discussion among netizens. One video depicted Messi quickly leaving the stadium without engaging with fans, while another showed a furious supporter kicking over Messi’s advertising board. Enraged fans flooded Messi and the team’s social media platforms with comments, demanding refunds and an apology.

On major football social media platforms in mainland China, such as Dongqiudi (懂球帝) and Hupu (虎扑), netizens engaged in heated discussions. Some expressed understanding, stating that if Messi was injured and couldn’t play, fans should be more tolerant. However, a majority of fans voiced anger and found it hard to accept.

A Web of Confusion

So what actually happened in Hong Kong? In the days following the controversial match, different speculations arose about Messi’s absence, creating a web of confusion. Regarding the team line-up, the stadium’s player list indicated that Messi was on the substitutes’ bench, which meant that he might play in the game. However, in the official Inter Miami CF lineup released on X before the game, Messi was not included at all.

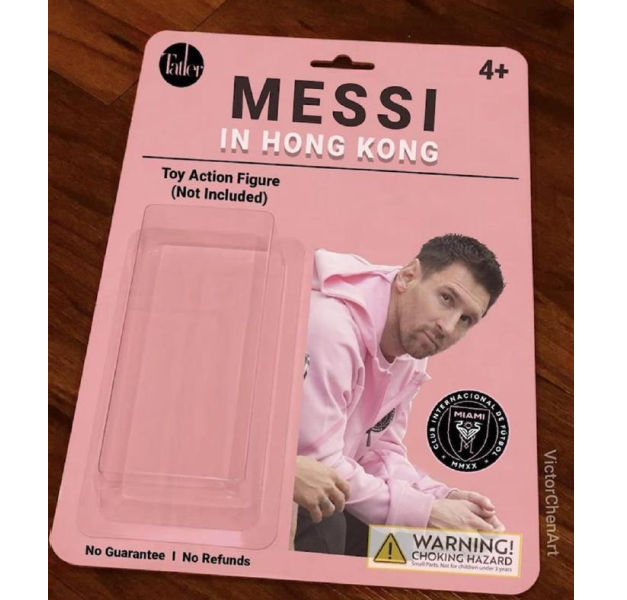

Messi is missing, artwork by the Hong-Kong based Victor Chen.

Contradicting reports on contractual obligations also came out. According to a report by Hong Kong Economic Daily, the contract only stipulated the presence of star players without guaranteeing Messi’s appearance. Newspaper Ta Kung Pao, however, reported that the contract between Inter Miami and Hong Kong stipulated Messi’s presence on the field for at least 45 minutes unless injured. Tatler Hong Kong, the organizer of the exhibition game, confirmed this, and stated that they were only informed about Messi’s absence at halftime. Soon after that, Kenneth Fok Kai-kong, current chairman of Hong Kong Arts Development Council, posted on his Weibo that the organizers were actually not informed at halftime but only ten minutes before the end of the match.

In the post-match press conference, the coach of Inter Miami explained Messi’s absence, saying that the decision was made by the medical team on the morning of the match. At a press conference in Japan, Messi himself stated that there was some discomfort in his adductor muscles, with swelling revealed in the MRI results. It was not classified as a muscle injury, but still caused discomfort. However, Messi’s official account on Weibo contradicted this by stating that the footballer has an injury to the “abdominal muscles”. The inconsistency added fuel to the fire, leaving fans feeling hurt and enraged.

As time went on, the conflicting information grew, without any clear answers emerging. Currently, the specifics of the contract between Inter Miami and the Hong Kong organizers remain undisclosed. However, on Weibo, users drew their own conclusions, making the hashtag “Messi breaks commercial bottom line” (#梅西爽约突破商业底线#) a trending topic.

A Political Battleground

The Messi storm still hasn’t blown over. Following the Hong Kong controversy, Messi came on as a substitute in Miami’s game against Vissel in Japan and his 30-minute stellar performance sparked heated debates on Chinese social media. Messi’s appearance in Japan was interpreted as him being “pro-Japan” and “anti-China,” turning a simple exhibition match into a political battleground.

A controversial video of Messi not shaking hands with the Chief Executive of Hong Kong and other government officials at the awards ceremony has been widely seen as a sign of disrespect toward Hong Kong and the Chinese government. As anti-Japanese sentiments surged, accusations against Messi flooded football forums.

A video titled “Messi’s Double Standards in Japan” by football influencer “Dishang zuqiu” (地上足球) gained significant traction. Among other things, the vlogger alleged that during Messi’s time at PSG, he used Japanese kanji on his kit, while all his teammates used proper Chinese characters to celebrate Chinese New Year. This video quickly gained over 2 million views, intensifying accusations of Messi’s anti-China stance. “I am a football fan, but first, I am Chinese,” expressed disappointed fans in various comment sections.

Despite its seeming absurdity, Messi’s absence has really become a political affair. The Hangzhou Sports Office issued a statement citing “obvious reasons” for the cancellation of the two friendly matches the Argentine national team had planned to play in China in March. The Chinese Football Association also suspended cooperation with the Argentine Football Association, removing all news related to Messi from its official website and social media.

Five days after the incident, media personality Hu Xijin posted on Weibo, stating that this matter “should not be politicized”, while emphasizing that “Messi is not that influential”, and suggesting that Chinese people should “look down upon” Messi.

On February 9, the eve of the Chinese New Year, Tatler Hong Kong, the organizer of this exhibition match, finally released a statement saying that they would offer those who purchased a ticket a 50% refund. They admitted that the contract stipulated Messi had to play for at least 45 minutes unless injured. Additionally, they revealed that upon learning Messi couldn’t play, they requested explanations from both Miami and Messi, which, unfortunately, did not materialize. The statement also expressed the organizers’ disappointment upon discovering that Messi still played in Japan, feeling it was “another slap in the face.”

In the summer of 2023, it seemed like Messi’s popularity in China had reached its peak during a friendly match between Argentina and Australia held at Beijing’s Workers’ Stadium when a Chinese fan stormed onto the pitch and embraced Messi. The incident went viral and only garnered more appreciation for the soccer superstar, who extended his arms and reciprocated the hug. Now, eight months later, Messi’s reputation in China has hit rock bottom.

The Hong Kong match and its aftermath will have lingering consequences for Messi. Not only have his matches in China been canceled, but it will also take time and effort to win back the hearts of Chinese soccer fans. “We now know how much you love Japan. China doesn’t welcome you anymore. Don’t come back,” one person posted on Messi’s Weibo page, where the footballer expressed his disappointment about not being able to play in Hong Kong and wished his fans a happy Chinese New Year.

For now, many fans are still left annoyed and puzzled, with many believing that Messi purposely did not appear at the Hong Kong match.

One Chinese football fan writes on Weibo: “I believe that Messi’s actions during this trip to Hong Kong are highly likely to be politically motivated. Whether this was because he was involuntarily influenced by powerful forces or because he is actively involved in politics himself, I don’t know, and I don’t want to know. Anyway, I’m no longer a fan.”

Update 2.19:

On February 19, the hashtag “Messi responds” (#梅西回应#, 320 million views by Monday night) went top trending on Weibo after Messi posted a video to his account. He wrote: “Happy Year of the Dragon, soccer friends! 🐲 Through this video, I want to clear up some things and once again express my gratitude to all the fans who came to support me and the team in Hong Kong, China. Thank you for your cheers, for your tifo support and love. Giving everyone a big hug 🙏🏼⚽️”

In the video, Messi states he wants to give his fans the “true version” of what happened in Hong Kong to avoid further speculation. Firstly, Messi denies that there were any political reasons for him not playing in Hong Kong or playing in Japan, stressing that he has visited China many times before since the start of his career: “I’ve had a very close and special relationship with China. I’ve done lots of things in China: interviews, games, and events. I’ve also been there and played many times for FC Barcelona and the national team.”

Messi then goes on to say that the reason he did not play in Hong Kong was because of an inflamed adductor, which got worse during his game in Saudi Arabia. As he really was not feeling well enough, he could not play in Hong Kong. As his situation improved, he was fit enough to play for a bit in Japan, “because I needed to play and get back up to speed.”

He adds: “As always, I send good wishes to everyone in China, who I’ve always had and continue to have special affection for. I hope to see you again soon.”

Although many fans do appreciate Messi’s statement, there are also numerous commenters on Weibo who still criticize the soccer player for not disclosing his injury earlier and lament the confusing communication surrounding the Hong Kong match, arguing that this video does not set the record straight.

This video marks Messi’s third response to the situation, following a press conference and a short Weibo post. The hashtag “Messi’s Third Response” (#梅西的3次回应#, #梅西3次表示希望再来中国#) also became a related hashtag.

Following all statements, some people have also had enough by now: “Are we done yet? Is it clarified enough now?”

Others argue that it might have been better for Messi not to post the video at all, as it reignites another social media storm just as the first one was calming down. The fact that the video was edited in the middle led to speculation about the omitted parts: what did he originally say? Why didn’t he release a video sooner? And why was Messi standing with his hands in his pockets?

In this way, the video seems to have a reverse effect, and however well-intended it may have been, it appears Messi is actually shooting himself in the foot.

By Ruixin Zhang and Manya Koetse

Featured image based on image posted on Weibo by @葡萄味的草莓萝妮

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Ruixin is a Leiden University graduate, specializing in China and Tibetan Studies. As a cultural researcher familiar with both sides of the 'firewall', she enjoys explaining the complexities of the Chinese internet to others.

China Memes & Viral

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

The meeting between US President Donald Trump and new Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi became a popular topic on China social media, thanks to a stream of meme-worthy moments.

Published

3 weeks agoon

November 2, 2025

It was a pleasant autumn day in Tokyo on October 28, when Trump first met Japan’s newly-elected Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi (高市早苗).

Takaichi welcomed Trump at the State Guest House as her first foreign guest since taking office as Japan’s first-ever female leader, offering what Yomiuri Shimbun described as “Takaichi-style hospitality.”

During the visit, Trump and Takaichi held a bilateral summit during which Takaichi expressed desire to build a new “golden age” for the US-Japan alliance. Afterwards, they signed agreements and exchanged gifts — a golf bag for Trump, signed by Japanese golf star Hideki Matsuyama (with whom Trump has previously played), and “Japan is Back” baseball caps for Takaichi.

Following a lunch that featured Japanese vegetables and American steak, the two visited the US Navy’s Yokosuka base, where Trump remarked that he and Takaichi had “become very close friends all of a sudden.”

On Chinese social media, the meeting drew considerable attention.

There has been heightened focus in China on Sanae Takaichi beyond anti-Japanese sentiment and her recent appointment as Japan’s first female Prime Minister — as she is widely regarded as a far-right politician who denies, downplays, or glorifies historical facts related to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1931-1945).

Japan’s official narrative of its wartime past has long been a major obstacle to deeper reconciliation between China and Japan, and it is highly unlikely that Takaichi’s views of the war are going to bring China and Japan any closer. Among others, she is known for visiting Yasukuni Shrine, the Tokyo shrine that honors Japan’s war dead (including those who committed war crimes in China). She also claimed that Japan’s aggression following the Manchurian Incident, which led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, was an act of “self-defense.”

In light of these tensions in Sino-Japanese relations, and because of the changing dynamics in the current US-China relationship, many details surrounding the Trump–Takaichi meeting became popular talking points.

🔴 Trump: Reaffirming US Dominance, Insensitive to Japan’s Wartime Past

Many netizens focused on moments they interpreted as Trump asserting dominance or showing disregard for Japan.

👉 One awkward moment showed how, during the welcoming ceremony, Takaichi failed to properly escort the US president. He walked ahead of her twice, and, despite the cues to salute the Japanese flag, Trump simply walked past it instead, leaving Takaichi looking visibly surprised (video).

While some saw it as a case of poor etiquette instructions behind the scenes, most reactions framed it as a sign of power dynamics in the US–Japan relationship, with some commenting: “Why would the master bow to his son?” (Hashtags: “Trump Skips the Japanese Flag” #特朗普略过日本国旗# and “Trump Ignores Takaichi Twice in a Minute” #特朗普1分钟内两次无视高市早苗#)

👉 Another widely discussed moment came at the Yokosuka base, where Trump invited Takaichi on stage and mentioned how their bond was based on WWII (“Born out of the ashes of a terrible war”) — a comment that seemed to catch Takaichi off guard (video). He quickly followed up with, “our bond has grown into the beautiful friendship that we have,” but not before her expression visibly changed.

Under the hashtag “Trump’s Remark Gave Takaichi a Scare” (#专家:#特朗普一句话吓了高市早苗一大跳#), Chinese media outlet Beijing Time (@北京时间) commented: “She was afraid that Trump might go on to say something she couldn’t respond to easily.”

Image by online creator.

👉 Later, at a reception at the US Embassy in Tokyo, Trump referred to the Pacific War as a “little conflict.” While the euphemism may have been aimed at promoting reconciliation (“We once had a little conflict with Japan — you may have heard about that — but after such a terrible event, our two nations have become the closest of friends and partners…” video), many Chinese netizens and outlets, including The Observer (观察者网) interpreted the remark as dismissive. This fueled hashtags like “Trump Calls the Pacific War a Small Conflict” (#特朗普将太平洋战争称作小冲突#) and “Trump Refers to Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombing as a Small Conflict” (#特朗普称轰炸广岛长崎只是小冲突#).

🔴 Takaichi: Smiles & Body Language Seen as Deferential to US

Alongside critiques of Trump’s behavior, much attention was also paid to Takaichi’s facial expressions and body language.

On Chinese social media, she was widely seen as overly eager to please — described as “fawning over Trump” (谄媚) in an “exaggerated” (夸张) way. Global Times highlighted how even Japanese netizens were criticizing her gestures as inappropriate for a prime minister (#日本网民怒批高市早苗谄媚#).

Some jokingly drew comparison to the famous movie about Hachiko, the loyal Japanese dog and his owner, played by American actor Richard Gere.

Some commenters described her behavior as that of an affectionate “pet” eager for approval.

Meme in which Takaichi was compared to Captain Jia (贾贵), known for his exaggerated flattery and traitorous behavior.

One meme compared Takaichi’s expressions toward Trump to those of Chinese actor Yan Guanying (颜冠英), who played the supporting role of Captain Jia (贾贵) in Underground Traffic Station (地下交通站), a satirical Chinese sitcom set during the Japanese occupation. The character was known for his exaggerated flattery and traitorous behavior.

🔴 Trump & Takaichi: A US-Japan Love Affair

But the most popular kind of meme surrounding the Takaichi-Trump meeting portrayed them as a newly smitten couple or even newlyweds. AI-generated images and playful commentary suggested a “love affair” dynamic. Watch an example of the videos here.

AI-generated images circulating on social media.

Some netizens linked this imagery to deeper historical dynamics — drawing distasteful parallels to American troops in postwar Japan and the women involved with them, including references to the reinstatement of the “sexual entertainment” industry once used to serve US forces.

For many, however, it was more about humor than history.

Some shared images showed just how much happier Trump seemed to be meeting with Sanae Takaichi than with her predecessor, Shigeru Ishiba, in 2024.

A considerably warmer meeting.

In the end, there are two sides to this peculiar “love affair” meme.

👉 On one hand, it plays on the affectionate behavior and newfound friendship between the two — Trump held Takaichi close to him multiple times, and she said she would nominate him for the Nobel Peace Prize. At the same time, the portrayal reduces Takaichi to a submissive romantic partner rather than a political equal, reinforcing gendered stereotypes — a dynamic that likely wouldn’t have emerged as strongly if she were a man.

This kind of “couple pairing” is quite ubiquitous in Chinese digital culture, especially involving people who are unlikely to have an actual relationship in real life. And although censorship would never allow this kind of pairing to thrive online if it involved Chinese politicians, the fact that it features Trump and Takaichi makes it less susceptible to online control.

A previous example of a noteworthy “love affair” meme was the one pairing US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi with Chinese political commentator Hu Xijin (see it here).

👉 Second, the Trump–Takaichi meeting is often placed in a Chinese context — showing the two getting married in a Chinese-style ceremony or inserting them into Chinese film scenes. While this may seem like light banter, it also reveals a deeper layer to the discussion: many believe that China plays a central role in the US–Japan relationship, interpreting the meeting through a Chinese lens in which US–China dynamics and the history of Sino-Japanese war are all interconnected.

Will they live happily ever after? Some may fantasize they will — but others think the weight of the past, both American and Chinese, will always cloud their sunny future. For now, most enjoy the banter and how “political news has turned into a romance variety show” (“政治新闻愣成了恋综了”).

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China World

“It’s in the Details” – The Xi-Trump ‘G2’ Meeting on Chinese Social Media

“The tariff drama, directed by Trump himself with himself as the main actor, has finally come to an end.”

Published

4 weeks agoon

October 30, 2025

Last update 1 November 2025

The meeting between Xi Jinping and Donald Trump has been a major topic across Chinese social media, from the announcement of the big ‘G2’ summit to the actual meeting between the two nations, which have been caught up in trade tensions and rocky relations.

The announcement and actual meeting became the top trending topic across Chinese social media platforms over the past week.

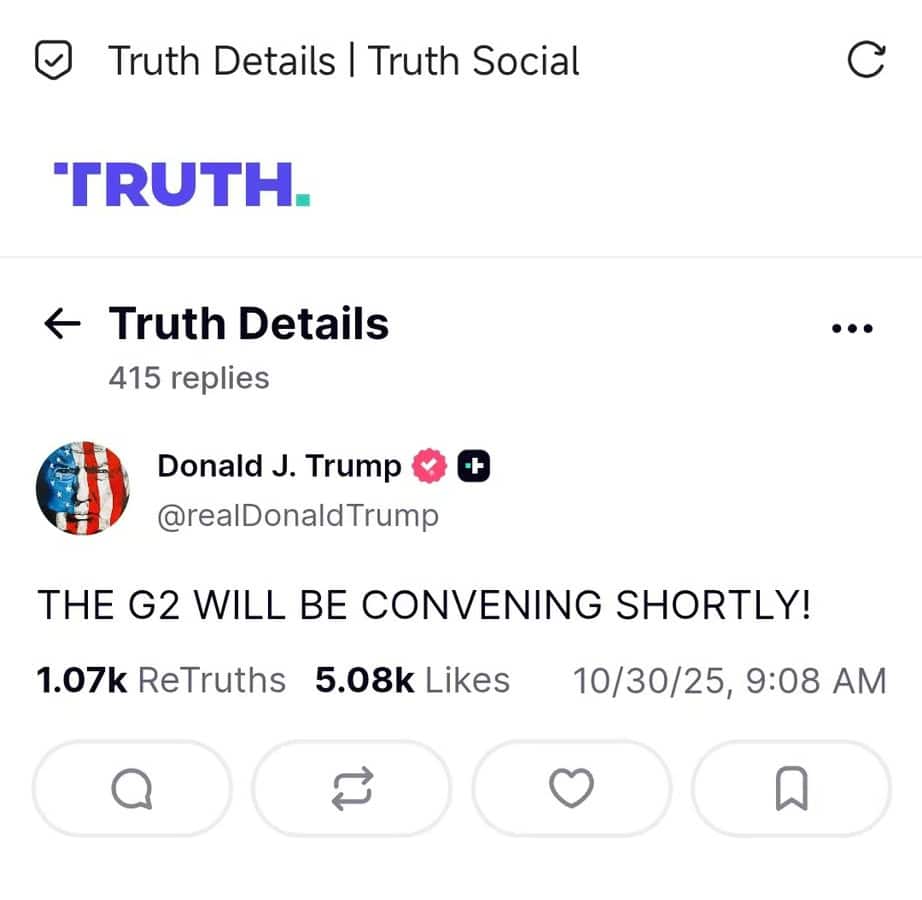

Trump announced the meeting with Xi as the ‘G2’ on his Truth Social platform.

The meeting, that lasted approximately 1 hour and 40 minutes inside Gimhae International Airport in Busan, South Korea, was the first in-person meeting between Trump and Xi since Trump began his second term in January 2025. The summit took place on the sidelines of the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) meetings and concluded Trump’s ‘Asia tour’ that also included visits to Malaysia and Japan.

Chinese news reports about the meeting were overall positive, with Xinhua noting that the two leaders agreed to strengthen cooperation in various areas and promote “people-to-people exchanges.”

State-run media also reported Xi’s emphasis on dialogue over confrontation and highlighted Trump’s praise of China. Reports by CCTV and China Daily emphasized Xi Jinping’s remarks during the meeting on the important of stable US-China relations: “The partnership and friendship of our two countries, is a lesson from history, and also a necessity of the present” (“两国做伙伴、做朋友,这是历史的启示,也是现实的需要”).

During the meeting, Xi also said that, given the differences in national conditions, some US-China disagreements are inevitable, and as the world’s two largest economies, “occasional friction is normal” (“两国国情不同,难免有一些分歧,作为世界前两大经济体,时而也会有摩擦,这很正常”). He added: “To face rough waters and challenges, both heads of state should steer the right course and keep the larger picture in mind to ensure the steady sailing of China–US relations” (“面对风浪和挑战,两国元首作为掌舵人,应当把握好方向、驾驭住大局,让中美关系这艘大船平稳前行”).

Trump told reporters that he rated the meeting with Xi “a 12 out of 10.” On Truth Social, he also called it a “truly great meeting” that resulted in some major agreements.

Among others, the US cut fentanyl-related tariffs on China from 20% to 10%, China agreed to pause its October 9 export controls on rare earths for one year, while Washington suspended related controls, and Beijing authorized massive purchases of American soybeans and agricultural products.

The two sides also agreed to maintain regular contact. Trump expressed his hope to visit China in April 2026 and invited President Xi to visit the United States.

G2: Changing Power Dynamics

Video footage showing Trump escorting Xi to his vehicle after the meeting went viral across platforms from Toutiao to Douyin.

As often happens in a social media environment where in-depth discussions of high-level meetings are heavily restricted, it’s the visuals that matter — with netizens dissecting the gestures and body language of both leaders.

One image that circulated online focused on the difference in body language between the Trump-Xi meeting and the meeting between Trump and Japan’s new leader Takaichi, suggesting it translates to different power dynamics.

Trump and Takaichi versus Trump and Xi.

On October 28, when Trump met with Takaichi, he appeared to ignore cues to salute the Japanese flag, instead briskly walking past it. Takaichi looked visibly surprised. While some attributed it to poor etiquette guidance behind the scenes, most reactions framed it as a reflection of the power dynamics in the US–Japan relationship — with the US clearly on top.

The smaller meeting moments and visual gestures of respect that Trump showed toward Xi were seen by many — including this Zhihu commenter, 高山流水教育者 — as important signs and changing US-China dynamics.

These gestures ranged from Trump arriving at the venue early and “respectfully waiting” (恭候) for the Chinese delegation, to being the one who extended his hand first during the handshake. After the meeting, both leaders smiled and Trump courteously escorted Xi to his car and exchanged a few quiet words with him (#特朗普送习主席上车#).

The commenter writes: “The truth lies in the details!” (“细节见真章” xìjié jiàn zhēnzhāng).

Another issue that has repeatedly come up on social media is how Trump prioritized a one-on-one meeting with Xi Jinping while skipping the APEC meeting — suggesting a preference for major power dynamics and his so-called ‘G2’ US–China alignment over broader engagement with the Asia-Pacific bloc.

Trump’s initiative to call the US-China meeting a “G2” seemed well-received by the Foreign Ministry of China, which responded to a reporter’s question about the use of this term on October 31. Spokesperson Guo Jiakun (郭嘉昆) suggested that China and the United States could demonstrate “major power responsibility together” by cooperating on issues beneficial to both countries and the rest of the world (#中方回应特朗普所称G2会议#).

The fact that Trump called it a “G2” speaks volumes for many about China’s strong global leadership today — especially coming from someone often described as having a “mentality of worshipping the strong” (慕强心理 mù qiáng xīn lǐ).

The media campaign China launched ahead of the Xi–Trump meeting to assert its claims over Taiwan may also have played a role — with a series of state media commentaries emphasizing reunification and the declaration of October 25 as “Taiwan Restoration Day,” there appeared to be added pressure to ensure Taiwan would not be used as a bargaining chip.

Taken together, the meeting and the details surrounding it are taken as a sign that Trump now accepts China as a stronger power than he did during his first term.

At the same time, Trump’s eagerness is also seen as a reflection of how his foreign policy efforts have fallen short in resolving domestic challenges. In that sense, his use of “G2” underscores both China’s rising position and the domestic pressures facing the United States.

With the fruitful outcome of the meeting and Trump showing clear respect toward China — and, as many suggested, even more respect than toward Japan — there seems to be a generally positive attitude and a noticeable shift in sentiment toward the US president on Chinese social media.

“Old Trump is an honest guy,” one person wrote on Weibo. Others on Douyin wrote: “US–China cooperation is a win-win situation.”

One observer on Weibo wrote: “The tariff drama, directed by Trump himself with himself as the main actor, has finally come to an end after all his tossing and turning. Life is like a play and it all depends on your acting skills. Old Trump treats politics as a show, which has broadened our horizons and added a bit of extra amusement to the world.”

By Manya Koetse

with contributions by Miranda Barnes

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral4 months ago

China Memes & Viral4 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained