China World

Frozen Europe and Fast-Changing China: Martin Jacques on the Sino-European Dilemma

Published

8 years agoon

British journalist and scholar Martin Jacques speaks about current Sino-European relations as a keynote speaker at the opening conference of the Leiden Asia Centre. According to Jacques, the way Western media and politics are approaching China is deeply flawed – and it is causing Europe to miss the boat while China is marching forwards. Live blogged.

February 9th 2017 marks the much-anticipated opening conference of the Leiden Asia Centre, the expertise centre for socially relevant and applicable knowledge on modern East Asia based in the Netherlands.

The conference focuses on Sino-Dutch relations and the relations between Europe and China at large.

One of today’s key speakers is British journalist and scholar Martin Jacques (@martjacques), the author of the global best-seller When China Rules the World (2009). One of his key arguments is that China’s impact on the world goes beyond economics, and that it will also have extensive political, cultural and ideological consequences.

“China is looking for the ‘cracks’ in the global system; that where it is at its weakest.”

In introducing Martin Jacques, Professor Frank Pieke, one of the three academic directors of the Leiden Asia Centre, first talks about a separate “global China”, that is different from Western patterns of globalization.

China is looking for the “cracks” in the global system; that where it is at its weakest. Its presence is growing in Africa, Latin America, and also in regions like southern Europe. China is not looking for challenges, but it is looking for space, Pieke says.

One of the reasons why this is happening, Pieke argues, is that China is hamstrung by the fact that within its own region it is often perceived as a potentially hostile power by, for example, Japan or Korea. It does not have its own sphere of influence from where it can expand into the world.

“China is not ‘like us.’ It has never been and it will never be.”

Martin Jacques agrees with Pieke in the sense that “China’s globalization” is different from “globalization” as it is often perceived in the West.

There is a fundamental problem with how China is framed and discussed in western media, politics and academia, Jacques argues, as it often come down to the idea that China should be ‘like us.’

“We are the ‘global leaders’ and we supposedly define what modernity is, and modernity is singular. And therefore modernisation is westernization, and therefore China will end up just like us. Well, this is complete rubbish,” Jacques says: “China is not ‘like us.’ It has never been and it will never be.”

Jacques stresses that the concept of ‘modernity’ is plural, and that there is not one modernity because it is not shaped in neo-liberal terms, but it is shaped by history and culture. And since China’s history and culture is profoundly different from that of any Western country, we have to understand China in its own terms – not in our terms. The main reason why Western media or politics got China “so wrong” in the last decennia, Jacques argues, is because they failed to do this.

The assumptions people have about China are therefore generally flawed, and have failed to predict how China would evolve in the future.

China is not a nation state, but a ‘civilization-state’, and is very different from any European nation state. It is a huge united country – and the fact that it is stable and unified is the country’s top priority. The key political values of the Chinese are influenced by this idea, and also fundamentally different from Europe.

Why China is politically never going to be the same as Europe is because its key political concepts of unity, stability, and order, based on its long history, are what have shaped and are shaping China.

“China has not followed anyone’s route, but has chosen its own.”

China has not followed anyone’s route, but has chosen its own, Jacques argues. “The idea that Chinese governance is going to be like Western governance is profoundly mistaken. China is not going in that direction. I am not saying they will not change – there have been large changes already – but it will change in its own ways.”

China is historically also very different from Europe in the sense that it has not colonized the way Europe has, and has been less aggressive.

“Consider that China from being dirt poor is becoming the world’s second economy, and this all in a relatively peaceful process.”

Jacques emphasizes that China is in the process of transforming the world. Not only due to its size, but also due to its difference, that is bound to going to project itself and bring its history, values, and traditions to the rest of the world.

“China is not the leader of globalization, but it is certainly true to say that China is shaping globalization profoundly.”

All discourse about China’s rise has always been economic – discussed within the framework of American hegemony. But Jacques wants to stress that the rise of China goes much further than economics alone: 1.4 billion people are in the process of transformation is all sorts of ways, which is impacting China and the world in numerous ways.

Jacques notes that China has sometimes been blamed for being a ‘free rider’ in the international society, or for not ‘contributing’ anything, but this is changing. Since Xi Jinping has risen to power there have been some extraordinary initiatives, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Jacques predicts that also through these kinds of initiatives, its influence is growing, and that those ever said China is not ‘contributing’ will be biting their tongues.

“It is not true to say China is the leader of globalization, but it is certainly true to say that China is shaping globalization profoundly.”

Jacques is pessimistic about the prospect of Sino-European relations. China is going ahead, and Europe is basically “stuck”, as it is increasingly turned inwards.

“Tencent, Alibaba, Huawei, Baidu, JD.com, Xiaomi, and other tech companies show that in many ways China is now ahead of Silicon Valley.”

Lastly, Jacques addresses the importance of China as a global power and crucial global influencer in various ways.

China’s online growth has shown it is the global leader in terms of internet commerce. Tencent, Alibaba, Huawei, Baidu, JD.com, Xiaomi, and other tech companies show that in many ways China is now ahead of Silicon Valley, with China’s online sales being well ahead of those in countries like the USA. Jacques also mentions that the functionality of apps like Weixin/WeChat is more advanced than its western counterpart Whatsapp – meaning that ‘the world’ will also be looking at China when it comes to its digital developments.

The country is also moving quickly in other ways. China is also the leader when it comes to issues such as climate change and foreign investments. He also mentions the ‘One Belt, One Road’ project (“it’s probably going to be extremely important.”)

“If Europe can’t hitch a ride with China in its transformation, then it will become marginalized.”

There is one last thing Martin Jacques wants to add to his speech, and it is about Trump, whom he calls “the most frightening president the US has ever had”, and how he will change the EU-USA-China dynamics.

Under Trump, he said, America will look after its own interests and will interact with the rest of the world in terms of bilateral relationships rather than from a plural, global position.

What will the Chinese do? “They will retaliate,” Jacques says. As China-US relations deteriorate, with China pushing America back, they will deepen the agreements with their own neighbors. The One Belt, One Road is an important part of this strategy.

Jacques foresees that the rise of Trump will also change Sino-European relations, as Europe -like China- also has little interest in Trump.

“I started off by saying Europe and China are very different, which is true,” he says. But despite his somewhat pessimistic views on Sino-European relations that find its roots in the western frameworks applied to China, there is also some light at the end of the tunnel: “Unlike the USA, both Europe and China have a long history. And there has been little rivalry with China. There is a logic for Europe to move much closer to China.”

Jacques stresses the importance for Europe to keep up with China. It is not China that needs to change, he argues – Europe does.

“China will keep marching on. China will keep its dynamic transformation. It will continue to grow. China is not the problem. Europe is. And we need to face up to that. If we can’t hitch a ride with China in its transformation, then we will become marginalized.”

Liveblog ended

– By Manya Koetse

Follow on Twitter or Like on Facebook

What’s on Weibo is an independent blog. Want to donate? You can do so here.

[showad block=1]

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Insight

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

“This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should.”

Published

3 months agoon

April 5, 2025

“China’s countermeasures are here” (#中方反制措施来了#). This hashtag, launched by Party newspaper People’s Daily, went top trending on Chinese social media on Friday, April 4, after President Trump announced steep new tariffs on Wednesday, including a universal 10 percent “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods and especially targeting China with an additional 34% reciprocal tariff as part of so-called “liberation day.”

Countermeasures were announced on Friday. China’s State Council Customs Tariff Commission Office (国务院关税税则委员会办公室) issued an announcement stating that, starting from April 10, an additional 34% tariff will be levied on all imported goods originating from the United States, on top of existing tariff rates.

Other countermeasures include immediate export restrictions on seven key medium to heavy rare earth elements, which are important for manufacturing critical products used in semiconductors, defense, aerospace, and green energy.

“This won’t make America great again”

The official response to the tariffs, both from state media and the government, has been twofold: on the one hand, it criticizes the U.S. for placing American interests above the good of the global community, arguing that the move only hurts the U.S., its people, and the world. On the other hand, the Chinese side stresses that although they do not believe tariff wars are the answer, China is not afraid of a trade war and will not sit idly by, but will respond with equal measures.

Chinese official media have condemned the new tariffs, which led to the largest single-day market drop in years. Describing the reactions of various experts, Xinhua News highlighted a comment by a Croatian professor, stating that the policy will only increase export prices and worsen inflation, ultimately hurting middle- and working-class Americans — and noting that the policy “won’t make America great again” (不会“让美国再次伟大”).

The official announcement by Chinese state media regarding China’s countermeasures received widespread support in its (highly controlled) comment sections, with both media outlets and netizens echoing the message that China will not be bullied by the U.S.

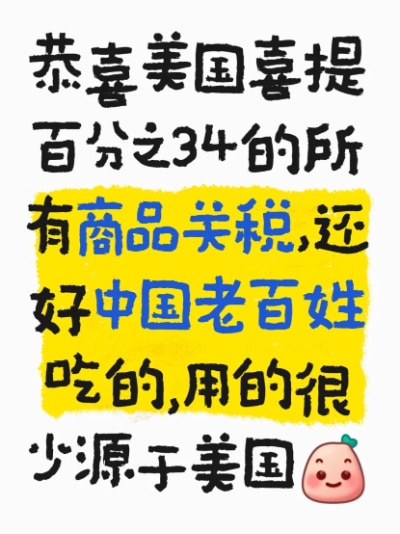

On Xiaohongshu, similar sentiments shnone through in popular posts, such as one person writing:

💬 “Congratulations to the U.S. on receiving a 34% tariff on all its goods! Luckily, very few of the things ordinary Chinese people eat or use come from the U.S. anyway.

#RMB purchasing power #China will inevitably be unified #Consumer confidence #Contemporary Chinese economy #Carrying forward the construction of a Beautiful China”

“Monday’s stock market will be a bloodbath,” another commenter wrote.

One Weibo blogger (@兰启昌) saw the recent developments as another sign of an ongoing trend of “de-globalization” (逆全球化).

But beyond global economics and geopolitics, many Chinese netizens — from Weibo to Xiaohongshu — seem more focused on how the new policies will affect everyday consumers.

Netizens have been actively discussing which goods will be hit hardest by the new tariffs. Based on 2023 trade data, here’s a breakdown of the top exports between China and the United States — and the sectors most likely to feel the impact.

🔷🇺🇸🇨🇳Top 10 Chinese Exports to the U.S.

1. Electronics and Machinery

Includes smartphones, laptops, tablets, integrated circuits, and image processing equipment.

2. Furniture, Home Goods & Toys

Such as video game consoles, lamps, and much more.

3. Textiles and Apparel

Garments, footwear, and accessories like sunglasses.

4. Metals and Related Products

Especially steel and steel-based items.

5. Plastic and Rubber Products

Widely used in packaging, manufacturing, and consumer goods.

6. Transportation Equipment

Electric vehicles, passenger cars, motorcycles, scooters, and drones.

7. Low-Value Commodities

Bulk items used in general trade and low-cost manufacturing.

8. Chemicals

Industrial chemicals and related materials.

9. Medical and Optical Instruments

Includes medical devices and precision instruments.

10. Paper Products

Ranging from office supplies to industrial paper goods.

🔹🇨🇳🇺🇸Top 10 U.S. Exports to China

1. High-Tech Machinery and Electronics

Especially integrated circuits, turbine engine components, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

2. Energy Products

Crude oil, liquefied propane and butane, natural gas, and coking coal.

3. Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals

Includes cosmetics, cleaning agents, and various medical drugs.

4. Soybeans

A key agricultural export widely used in food and animal feed in China.

5. Transportation Equipment

Such as automobiles and aircraft parts.

6. Medical and Optical Devices

Medical precision equipment, diagnostic tools, and lab instruments.

7. Plastic and Rubber Goods

Used in both consumer and industrial sectors.

8. Metal Products

Primarily iron and steel exports.

9. Wood and Pulp Products

Lumber, wood pulp, charcoal, and paper goods.

10. Meat

Including beef, pork, and poultry.

Those doing trade with the US, or otherwise involved in made-in-China products, like those working clothing and furniture factories, will inevitably be affected by the tariffs.

“Patriotism isn’t just a sentiment – it’s an action”

Much of the popular online conversation has focused on concrete examples of what kinds of things might get more expensive for Chinese consumers in their everyday lives.

Some bloggers noted that people might start to see price hikes in everyday groceries like dairy, meat, corn, and soybeans. With fewer soybeans coming in from the US, cooking oil prices may also rise.

China is the world’s largest consumer of soybeans, but because domestic production is relatively low, soybeans remain a key import.

Then there are popular American brands in the Chinese market that are expected to get pricier too — like beauty and health products, Starbucks coffee, or Häagen-Dazs ice cream.

Some also predicted a 30% to 40% increase in prices for iPhones and other Apple products.

Contrary to the earlier comment by the Xiaohongshu blogger, some netizens explain just how many American products are actually used by Chinese consumers, with many American companies operating in China — from McDonald’s and Coca-Cola, Walmart to Disney or Warner Brothers, Procter & Gamble to Colgate and Estée Lauder.

What’s noteworthy in these discussions, however, is a strong tendency to point to Chinese alternatives and encourage smart buying instead of following hypes (“理性替代,拒绝跟风”): No need to panic about soybeans — there are domestic alternatives, and China’s own soybean program is getting a boost. Who needs Starbucks when there’s Luckin Coffee? Why buy an iPhone when you can get a Huawei? Skip the Tesla, go for a BYD.

In these discussions, the ‘crisis’ is turned into an ‘opportunity’ for Chinese companies to focus even more on the Chinese market, and for Chinese consumers to, more than ever, actively embrace and celebrate local brands and made-in-China products.

One Chinese blogger (@O浅夏拾光O) wrote:

💬 “This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should. For example, we can use rapeseed oil or peanut oil instead of imported soybean oil; we can buy cost-effective Chinese electronics instead of foreign brands. Support domestic products and respond to the nation’s call to expand domestic consumption.

We must have faith in our country. Only by uniting as one, young and old all together, the entire country working together, can we withstand all hazards. As Professor Ai Yuejin (艾跃进) once said, patriotism isn’t just a sentiment – it’s an action. As long as our core is stable and we are united in spirit, no hardship can defeat us.”

Despite the major happenings and the big words, some people just care about the small things: “As long as KFC and McDonald’s don’t raise their prices, it’s all fine by me.”

See the follow-up to this article here.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

From shifting sentiments on Zelensky to a renewed focus on Taiwan, recent geopolitical developments have sparked noteworthy takes from Chinese online commentators.

Published

4 months agoon

March 9, 2025

As the Russia-Ukraine war enters its fourth year, Chinese social media is once again flooded with discussions about the geopolitical shifts triggered by Trump’s policies. From the Oval Office clash to Trump’s ‘pivot’ to Russia, this article explores how Chinese netizens are interpreting the rapidly changing geopolitical landscape.

Three years ago, when the Russia-Ukraine war first broke out, one particular word went trending on Chinese social media: wūxīn gōngzuò (乌心工作). The term was a wordplay on the term wúxīn gōngzuò (无心工作), meaning not being in the mood to work, and it basically meant that people were too focused on Ukraine to concentrate on work.

Although that word has since faded from use online, recent geopolitical developments surrounding the Russia-Ukraine war have once again drawn considerable attention on Chinese social media, where trending word data tools show that “Trump” and “Zelensky” are among the hottest buzzwords of the moment.

Trump Zelensky, Ne Zha, Lei Jun; biggest words of interest on, among others, Weibo, on March 4, 2025.

Trump’s recent rhetoric toward Russia, his remarks about Ukraine, and his attitude toward NATO not only mark a shift from Biden and decades of US policy, but also reshuffle the geopolitical cards and raise questions about the future of the postwar international order.

Where does China stand in all this?

➜ Although China’s online environment is tightly controlled, particularly regarding political discussions, what stands out in conversations around the recent developments involving Trump, Putin, and Zelensky is a widespread sentiment that — at its core — it’s all about China.

Many believe that China’s rise on the global stage, and the resulting US-China rivalry, are key forces shaping US strategy toward Russia as well.

Woven into these discussions are US-China trade tensions, with Trump increasing tariffs by 10% on February 1, and then doubling the tariff on all Chinese imports to 20% from 10% on March 4. This immediately prompted China to retaliate with 10-15% tariffs on US agricultural products, effective March 10.

Currently, developments are unfolding so rapidly that one hashtag after another is appearing on Chinese social media. “It’s not that I don’t understand, it’s just that the world is changing so quickly,” one Weibo blogger commented, referencing a famous song by Cui Jian (“不是我不明白,是这世界变化快”).

Amid this whirlwind of events, let’s take a closer look at the current Chinese online discourse surrounding the Russia-Ukraine war, with a focus on shifting attitudes toward Zelensky and US-Russian relations.

THE OVAL OFFICE INCIDENT

“Saint Zelensky is a real man!”

One major moment in the recent developments has been the clash between Zelensky, Trump, and US Vice President JD Vance in the White House Oval Office on February 28.

Zelensky had come to the White House to discuss the US’s continued support against Russia and a potential deal involving Ukraine’s rare earth minerals, but it ended in a heated confrontation during which, among others, Zelensky questioned Vance’s notion of “diplomacy” with Putin, and Trump and Vance expressing frustration with what they perceived as Zelensky’s ingratitude for US support.

On Chinese social media, the clash between Zelensky, Trump, and Vance in the Oval Office seemingly caused a shift in public views towards Zelensky and the position of Ukraine. Some commentators who are known to usually take a pro-Russian stance were suddenly positive about Zelensky.

“Zelensky is really awesome, he had a confrontation with Putin’s two top negotiators in the Oval Office and still managed to hold his own,” historian Zhang Hongjie (@张宏杰) jokingly wrote on Weibo.

Others compared compared Trump and Vance to “two dogs barking” at Zelensky, and saw the meeting as one that was meant to humiliate Zelensky.

Nationalist blogging account “A Bad Potato” (一个坏土豆, 335k+ followers) admitted: “I’ll lay my cards on the table: I fully support Zelensky.”

He further wrote:

💬 “Let’s not make any illusions. Trump’s ultimate target is China. (..). He’s already added two rounds of 10% tariffs on China. Isn’t it obvious? Did you think he is pulling closer to Russia for some big China-Russia-America unification? Once he’s done dealing with his internal problems, he’ll inevitably come at China with full force. There are some people here who are hoping for Zelensky to kneel before the US, and I’d like to ask these people: Whose side are you on? Are you on the Russian or American side? When Zelensky’s firm towards the US, of course I’ll support him. His performance was so perfect that I’d like to call him Saint Zelensky!

(..) Some say Zelensky’s betraying his country. So what if he is? As long as he’s not selling out China, he can sell out the whole world for all I care. Just look at the stupid and bad Macron, or Starmer who’s full of sneaky tricks, they’re getting humiliated by Trump in all kinds of ways. Then look at Zelensky again and let me shout: Saint Zelensky is a real man! He’s a tough guy! Of course, I’m keeping it balanced here—I support Russia too. Both sides must make an effort.”

➜ Although there is some pragmatism in this ‘pro-Zelensky’ shift, which is Sino-centric and mostly based on which actors in the political game are considered antagonists of China, there is also another level of sympathy towards Zelensky as the underdog in this situation — facing a 2-against-1 dynamic on unfamiliar terrain, while speaking a language that is not his.

Weibo user “Uncle Bull” (@牛叔, 820k followers) wrote:

💬 “The arguing scene in the Oval Office should be a reminder for every politician that it doesn’t matter how well you speak English, when it’s a formal occasion, you should always speak your native language and have a translator with you— it helps avoid a lot of direct confrontations.”

In his analysis of the situation, well-known political commentator Chairman Rabbit (兔主席) took a far more critical stance towards Zelensky, suggesting that his confrontational attitude in the Oval Office was misplaced and driven by personal pride, and that his actions in the White House caused it to be “the most disastrous trip in history.”

Chairman Rabbit also commented:

💬 “There is an ancient Chinese saying: “A man of character can bow or stand tall as required [大丈夫能屈能伸].” When it comes to major issues like the survival of the nation, things like some dignity and righteousness and principles all are meaningless. When facing Trump, you just have to flatter and appease him. If Zelensky is unable to humble himself, then he’s probably not suited for this job. It’s just as the most pro-Ukraine Republican senator, Senator Lindsey Graham, said – he suggests that Zelensky should step down, and Ukraine should find someone else to negotiate.”

But there are many netizens who do not agree with him, like this popular comment saying: “Whatever you do, don’t kneel [to Trump] — you’re a spiritual totem (精神图腾) for so many people on Weibo.”

TRUMP’S ‘PIVOT’ TO RUSSIA

“The US-Russia honeymoon has begun”

When US and Russian delegates sat down in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on February 18 to discuss improving Russia-US relations and ending the war in Ukraine—without Europe or Ukraine at the table—Chinese netizens pointed out that there were no plates on the table, joking that “Europe and Ukraine are what’s on the menu.”

They referred to a comment previously made by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken when replying to a question about US-China tensions leading to greater fragmentation: “If you’re not at the table in the international system, you’re going to be on the menu.”

The official Chinese response to the developments, as stated by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Guo Jiakun (郭嘉昆), is that China is glad to see any efforts that contribute to peace, including any consensus reached between the US and Russia through negotiations (#中方回应俄美代表团举行会晤#).

Among social media users, there was banter about the sudden US-Russia rapprochement, after news came out that the two countries intend to cooperate on various matters concerning their shared geopolitical interests (#俄美决定未来将在多领域合作#).

“The US-Russian honeymoon has begun [美俄蜜月开始]!” some commenters concluded.

“It won’t last more than four years,” others predicted.

Some suggested it might be an opportunity for China and Europe to draw closer: “China and Europe will also cooperate on various matters.”

Regarding Putin agreeing to assist in US-Iran talks (#美媒爆普京同意协助美促成与伊朗核谈判#), reactions were cautiously optimistic: “It’s hard to find an American president seeking peace as much as Trump is,” one Weibo user wrote. Another added: “He might be pursuing ‘America First,’ but his efforts for peace deserve some acknowledgement. I hope it’s true.”

➜ Outside of China, analysts and commentators have argued that a US-Russia rapprochement could be bad for China, suggesting it might undermine the close strategic partnership between China and Russia. However, this sentiment seems less pronounced on Chinese social media, where many argue US-Russian relations are bound to be fickle, while others echo the official stance.

The official response to such concerns, as stated by Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑), is that the China-Russia bilateral relationship “will not be affected by any third party”:

💬 “Both China and Russia have long-term development strategies and foreign policies. No matter how the international landscape changes, our relationship will move forward at its own pace. The US attempt to sow discord between China and Russia is doomed to fail.”

Another perspective comes from Chinese political scientist and commentator Zheng Yongnian (郑永年), in a recent interview with Xiakedao (@侠客岛), a popular commentary account from People’s Daily Overseas Edition.

Zheng noted that the US-Russia shift is not surprising—considering, among other things, Trump’s previous comments about his good relationship with Putin—but that it places Ukraine and Europe in an unfavorable position.

➜ Like other commentators, Zheng suggests that Trump’s strategy to improve ties with Russia is also linked to gaining leverage over China. However, he does not necessarily view it as a direct revival of Kissinger’s famous Cold War-era strategy, which aimed to align with China to counter the Soviet Union. In this case, it would be reversed: allying with Russia to counter China (“联俄抗中”). In Trump’s view, Zheng argues, Europe doesn’t matter, and Ukraine is insignificant. Russia is the key to maximizing US interests.

➜ Like others—and in contrast to some foreign analyses—Zheng does not see the U.S.-Russia rapprochement as necessarily harmful to China. Instead, he suggests that right-wing, pragmatic partners may ultimately be more beneficial to China than left-wing ideological ones, stating:

💬 “When it comes to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the previous Biden administration continuously tried to frame China, attempting to shift the blame onto China. So now, after the US and Russian leaders spoke, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded by saying they are ‘pleased to see all efforts working for peace, including Russia and the US coming to a common understanding that will lead to peace.’ China won’t meddle in another country’s internal affairs. No matter who’s in power, we will engage with them. China can indeed take a relatively neutral stance.

In the past, we said, ‘It’s easier to deal with the right-wing in the West.’ Why? Because the political right is less hypocritical; they value interests, and interests can be exchanged. Some Western left-wing factions, however, cling to ideological patterns, labeling and defining you, making exchange and interaction impossible.”

SHARPENED FOCUS ON TAIWAN

“Ever since Trump came to power and betrayed Ukraine, the rhetoric towards Taiwan has become increasingly tough”

Although there may be mixed views and different analyses, one thing is certain: Trump’s strategies are shaking things up from how they used to be.

➜ One thing that doesn’t change in rapidly changing times, is an overall anti-American sentiment on Chinese social media.

Even though some commenters appreciate Trump’s pragmatism or are entertained by the spectacle of US politics from the sidelines, there remains a strong belief that US strategies are ultimately aimed against China. This reinforces anti-American sentiments and fuels discussions about a potential US-China conflict.

This is especially tangible at a time when the US government has once again raised tariffs on Chinese imports.

“If war is what the U.S. wants—be it a tariff war, a trade war, or any other type of war—we’re ready to fight till the end,” China’s embassy in Washington posted on X, reiterating a government statement from Tuesday.

During the Two Sessions on March 7, Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) also commented on US-China relations, stating:

💬 “No country should harbor the illusion that it can suppress and contain China on one hand while seeking to develop a good relationships with China on the other. Such two-faced behavior [两面人] is not only detrimental to the stability of bilateral relations and cannot build mutual trust.”

➜ Against this backdrop, the Taiwan issue has once again come into sharp focus.

This is partly driven by the two Two Sessions (March 5-11), China’s annual gathering of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). This is not just a major political event but also a key moment for propaganda and political messaging.

But it is mostly linked to the broader, rapidly changing geopolitical sphere and Trump’s shifting stance on Russia and Ukraine. The narrative of US power politics failing to change the course of a China-Taiwan “reunification” is surfacing again precisely because of Trump’s reshuffling of alliances.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Chinese social media users have frequently drawn comparisons between Taiwan and Ukraine. The phrase “Today’s Ukraine, tomorrow’s Taiwan?” gained traction at the time, as online commenters saw Ukraine’s rapid invasion as a cautionary tale for Taiwan, highlighting how quickly the situation could change. A viral meme from that period depicted a pig labeled “Taiwan” watching another pig, “Ukraine,” being slaughtered.

A meme circulating on social media in 2022 showing a pig “Taiwan” watching the slaughtering of another pig “Ukraine.”

This week, Chinese state media launched a large-scale social media propaganda campaign using strong language and clear visuals to reinforce the narrative that Taiwan is not a country, that it is part of China, and that reunification is inevitable.

Such rhetoric has appeared before, with similar peaks in Taiwan propaganda dating back to at least 2022. The topic of Taiwan has often been amplified during key political events, such as the 20th Party Congress and Xi Jinping’s speech in October 2022.

“Have you noticed?,” Weibo author Yangeisaibei (@雁归塞北) wrote: “Ever since Trump came to power and sold out Ukraine, the rhetoric towards Taiwan has become increasingly tough, the tones become more stern, and the words more straightforward.”

According to prominent Weibo blogger @前HR本人, who has over two million followers, the Taiwan issue is now more important than before.

💬 “When it comes to foreign struggles, resolving the Taiwan issue is China’s top priority. Judging from the Chinese Embassy in Washington declaring “We are not afraid of any kind of war with the US”, it seems we are already preparing to reunify Taiwan at any moment.”

Another Weibo blogger (@王江雨Law, 419k fans) wrote:

💬 “Now that all kinds of big and smaller developments are changing the [political] climate, especially if America’s strong territorial expansion claims turn into concrete actions, this could trigger synchronous reactions, greatly increasing the possibility of resolving the Taiwan issue within a few years. We need to rethink the previous view that the mainland is not in a hurry on this matter.”

What emerges from these discussions is that Chinese online discourse on the Russia-Ukraine war and US foreign policy is primarily centered around two key ideas:

🔸 The belief that China is ultimately at the core of US geopolitical strategies in its dealings with Russia.

🔸 A pragmatic, Sino-centric view in which support or opposition to leaders like Trump, Putin, or Zelensky shifts depending on what serves China’s interests best.

Rather than seeing the conflict in black-and-white terms, many Chinese netizens approach it as a dynamic political chess game, one in which China should play a smart and confident strategy.

Politics-focused blogger Mingshuzhatan (@明叔杂谈, 137k followers) wrote:

💬 “In the process of this game against US, we must respect them in tactics, and contempt them in strategy [战术上重视、战略上藐视] – stay patient and confident. Trump is currently going against the tide, he’s being destructive. But actually, this recklessness is damaging US credibility and its global influence, it will accelerate the decline of American hegemony. A silent majority of countries in the international community harbor growing resentment and disappointment toward the US, and when these sentiments reach a tipping point, America will truly experience the pain of “un unjust cause draws little support” [失道寡助]. China, on the other hand, although also facing some challenges, focuses on science and technological and industrial innovation. That’s the right path for China’s long-term stability, prosperity, and security. In the China-US competition, it is becoming increasingly evident that time is on China’s side.”

This perspective reflects a dominant theme across Chinese online discussions: No matter how intense the geopolitical shifts may be, or how much the US reshuffles its global strategy, China remains on its course and is playing the long game.🔚

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Jiehun Huazhai (结婚化债): Getting Married to Pay Off Debts

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Lured with “Free Trip”: 8 Taiwanese Tourists Trafficked to Myanmar Scam Centers

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Media12 months ago

China Media12 months agoA Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoThe “City bu City” (City不City) Meme Takes Chinese Internet by Storm

-

China Society9 months ago

China Society9 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media